Figure 1. Thin-section microscope slides by “H.C.B.”, who my research indicates was Henry Charles Beasley. Prepared ca. 1880 - 1919.

Henry Charles Beasley, 1836 - 1919

by Brian Stevenson

last updated June, 2024

A number of thin-sectioned mineral microscope slides are known that carry labels with the printed initials “H.C.B.” Evidence presented below indicate that their maker was Henry Charles Beasley. He was an expert geologist who frequently wrote on using microscopes to examine fine structures of fossils and other rocks, including methods by which to prepare mineral thin-sections.

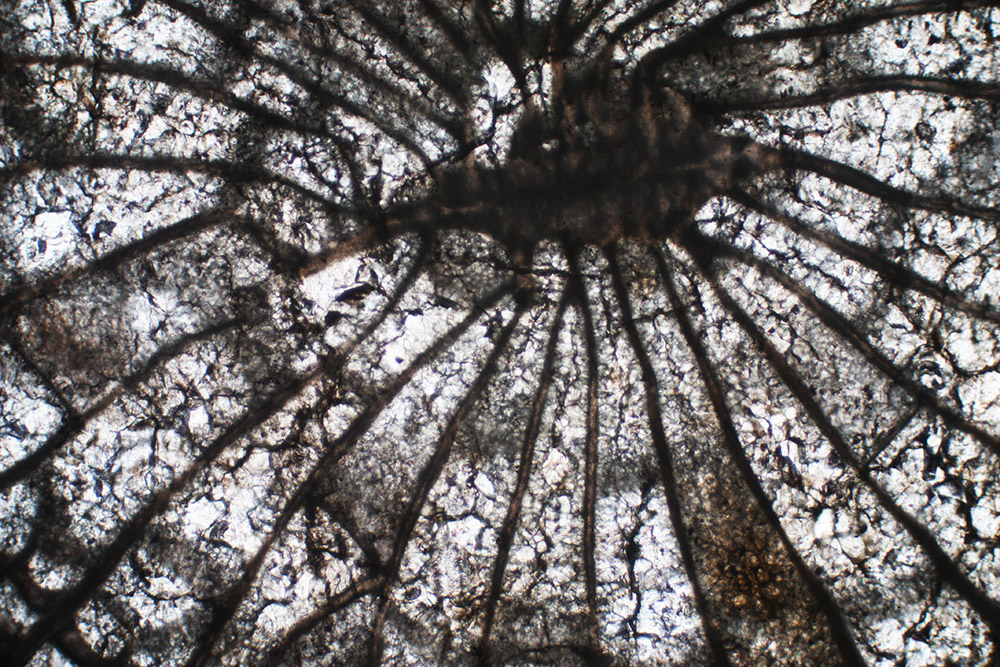

Figure 1.

Thin-section microscope slides by “H.C.B.”, who my research indicates was Henry Charles Beasley. Prepared ca. 1880 - 1919.

Figure 2.

“Section of fossil coral from Llandudno” (see Figure 1). Imaged with a 3.5x objective lens, transmitted light, and C-mounted digital SLR camera on a Leitz Ortholux II microscope.

Figure 3.

An undated photograph of Henry Charles Beasley.

H.C. Beasley is the top candidate for having been slide-maker “H.C.B.” due to his interests in geology (Beasley was a long-time member and officer of the Liverpool Geological Society), a heavy bias of known specimens to origins near his home of Liverpool, his numerous papers on microscopical examination of mineral specimens, and he being an expert in preparing thin-sections of minerals for microscopical examination. In 1883, Beasley published, “On the preparation of rocks for microscopical examination”:

“I propose in the present paper to give an account of the methods I have myself found most convenient for preparing specimens of rocks for examination under the microscope, with such appliances as may be readily obtained at a small cost; and I shall presume, at the outset, that the object is the examination of specimens collected in the field by the practical geologist, and not the manufacture of microscope slides on an extensive scale.

I will, in the first instance, take for example a piece of ordinary carboniferous limestone, as being a rock of average hardness and compactness, and afterwards shew the somewhat different treatment required by the softer rocks on the one hand, and the harder rocks on the other.

(1) The first operation is to procure a thin flake of the rock, say about an inch across this can often be done by a smart blow of a hammer near the edge, but it can generally be insured by holding the specimen of the rock in one hand on a cold chisel fixed to a block of wood, or on the sharp end of a geological hammer, and striking it a sharp blow with a hammer with the other hand.

(2) The next operation is to grind one side quite flat. The quickest way of doing this is by rubbing it on a flat piece of hard sandstone, about 14 ins. by 10 ins. sprinkled with coarse emery powder, and kept well wet. A flat piece of iron, or a piece of plate glass is very handy, in case you are travelling about, instead of the flat sandstone, but it does not grind so rapidly, as of course the grinding is in that case done by the emery alone.

(3) Having got a flat surface right across the flake, the next process is to remove the roughness. For this I generally use an emery hone of medium fineness, but a piece of plate glass with fine emery is very good. Great care must be taken that none of the grains of coarser emery used in the previous process adhere either to the specimen or to the plate glass, otherwise deep scratches will result, which will require a great deal of labour to get rid of; the specimen must therefore be carefully washed between each operation. I prefer the emery hone to the plate of glass, as there are fewer loose particles of emery about.

(4) As soon as you have rubbed it as smooth as possible on the emery hone, wash it carefully, and then rub it with a somewhat circular motion on a water of Ayr stone, and if you are careful not to have any bits of grit or emery about, you will in a minute or so have a surface free from scratches. Instead of the water of Ayr stone, another plate of glass may be used with very fine emery powder. The glass has the advantage of preserving an even surface, whereas the emery stone and the water of Ayr stone will wear into hollows, however careful you may be to distribute the friction over the whole surface; but they can be readily ground smooth on the sandstone slab used for the first process, and will at the same time tend to produce an even surface on that, and I think that the little trouble is quite compensated by the absence of annoyance from the dirt and grit that always is liable to get about, when emery powder is used. Having freed the surface from scratches, it will be advisable to examine the specimen under the microscope as an opaque object. By wetting the surface and throwing a strong light upon it through a bulls' eye condenser, you will readily make out a good deal of its structure, and that of the minute fossils it contains. Some rocks lend themselves much more readily than others to this mode of examination. If this seems likely to be the case in this instance, it will be well to proceed to polish the specimen. In most cases a thin film of moisture will render the features very distinct, and for rocks that will not readily take a polish, a good way to examine them is to cover the smooth surface with a thin coat of Canada balsam, and cover it with a thin piece of glass. Of course, however, the result is not nearly so satisfactory as when a fine polish has been given to the surface; and this may generally be done by getting as fine a surface as possible on a German hone, or some similar stone, and then polishing it upon a piece of coarse felt well sprinkled with the very finest ‘putty powder’ (muriate of tin) obtainable. It should be kept just damp during the operation. Do not let the felt get at all saturated with water.

(5) We will now return to the piece reserved for a transparent section, and which has been rubbed down to a tolerably smooth surface. We next procure a piece of plate glass 1 in. or 2in. square, and on to this we fasten the smooth side of our specimen. The best substance for this purpose is Canada balsam; it can be procured at any chemists, and is generally sold in too soft a condition for use for this purpose, so it will be necessary to heat it in an open vessel (I generally use a porcelain dish) for some hours, taking care that it does not boil, or the bubbles formed will be a great trouble in succeeding operations. The balsam should be tried from time to time. by taking out a small portion on a steel rod, knitting needle, or knife, and cooling it, and when it is hard enough to resist the pressure of the thumb nail, it should be at once removed, as if it is further heated it will become too brittle to use.

Heat the specimen and the piece of glass until as hot as you can bear to touch with the finger, then place a portion of the hardened balsam on the piece of glass, where it will melt, and press the flat surface of the specimen firmly upon it, moving it a little to get the melted balsam evenly spread beneath it to expel any bubbles that may have formed.

When the balsam has thoroughly set, you can grind the stone away with your coarsest emery till it is about 1 in. thick, the square of glass serving as a convenient handle; then it will be advisable to use the finer emery or hones as directed before. It is important now to get as perfectly level a surface as possible, so care must be taken to hold the specimen firmly in one position while using the finer hones. By the time all the scratches are removed the stone will be about 1 in. thick, and it will be advisable to put a fine polish upon it, unless there are any interstices in it, which would hold the putty powder, in which case it is better to finish it on a plain piece of leather. The specimen by this time will probably be somewhat less in diameter than it was, but if not more than an inch in one direction it will make a very good slide, and of course the larger the better, if well done; but practically you will find that it is better to divide it into smaller pieces, therefore just mark it across with a knife, scratching it as deeply as you can, and dividing it into portions about in. square.

You now take the square of glass and scrape off all the balsam you can that may surround the specimen, and then warm it, and when it is thoroughly warm a gentle but firm lateral pressure with a blunt instrument, say the handle of your forceps, will cause the thin section to slide off the glass. Drop it into a watch glass filled with benzine, and when it has soaked a little time, wash it thoroughly with a camel hair brush, and get rid of all the balsam that may adhere to it. Break it across where you scored it with the knife. Each piece is now smooth on one side, and more or less polished on the other; the polished side being finished must be attached to a little disc of thin glass termed a cover glass. These can be had of all sizes, and it is well to have an assortment, so as to be able to suit your specimens. A very convenient size is about gin. diam. and that will suit the present purpose.

(6) Your cover glasses being quite clean, warm both them and your specimens, and place on each cover glass a piece of balsam, and when melted lay a specimen, the polished side downwards upon it, pressing it firmly and moving it a little to expel any bubbles. A small brass or copper stand with a spirit lamp below it will be found most convenient for warming the glasses and specimen in this and subsequent operations; one can be obtained, made specially for this purpose at the microscope dealers, or can be quite easily made by oneself. If the rock be at all friable it is well to let it have enough balsam to thoroughly embed it.

Be careful that there are no bubbles or air spaces between it and the glass, and hold it firmly in a pair of forceps for a few seconds, till it is cool. Then take a narrow slip of glass, 3 in. x 1 in., such as are generally used for microscope slides, and attach your cover glass close to one end of it, with a bit of balsam. Press it down with a spring clip, and leave it for a few hours for the balsam to harden thoroughly, and treat the other pieces in the same way.

The glass slip serves for a handle, holding this grind the specimen on a water of Ayr stone till it begins to be somewhat transparent, and then finish it either on a very fine hone, or on a piece of plate glass with Rottenstone. This is perhaps the best, as it is important to grind it evenly, and the plate glass ensures an even grinding surface. The grinding must be done very carefully, and every minute or so it should be dipped in water, just washed with a brush, and examined with a lens, or else before you know where you are, it will be quite ground away, or have so broken up as to be useless. As soon as one piece has been made tolerably transparent, put it aside and proceed with the next and as you are now sure of one, you may try to make this next one thinner than the first; if you succeed in doing so, you can return to the first, and grind it to the same or a greater transparency. You next warm the glass slips, and very carefully slide off the cover glasses, with the objects attached to them, and wash them in benzine with a camel hair brush.

(7) The preparation of the object is now complete, and you proceed to mount it on a glass slip, so that it may be more readily handled and examined, without fear of injury. The best medium for this is Canada balsam dissolved in benzine, so as to be rather thinner than syrup. You take a 3 x 1 in. glass slip, and, having warmed it on the brass stand, drop a drop of the thin balsam in the centre, and then place the cover glass, with the object downwards, of course, upon it, letting one edge down first, and then closing it down like the lid of a box. Press it firmly down, and keep it so, either with a spring clip or lead weight; and leave it a short time, on the warm stand, but be very careful not to let it get hot enough to form bubbles (the thinner the balsam the less liability to bubbles). Then remove any superfluous balsam, and put the slide aside for some days, where it will be free from dust. When it seems quite firmly set, wash off any balsam that may be sticking to the glass with a camel hair brush and benzine, and wash off the benzine with another camel hair brush and some soap and water. When dry it is quite ready for the cabinet, but it will be better able to resist any comparatively rough usage or accident, if you put a ring of white cement round the edge of the cover glass. This is easily done with the aid of a brass turn table sold for the purpose.

I think that by following these directions, and with a little practice and delicacy of handling, some very fair slides may be turned out. You may, often, however, omit some portions of the process, and still make a very satisfactory examination of a rock. If you can manage to strike off a very thin flake about inch across in the first instance, you can readily smooth down one side, attach it to the centre of a slip, and grind it down there till transparent, and it is at once ready for examination. A corundum file will be found very useful in rapidly rubbing down small specimens; plenty of water must be used with it to keep it cool, as also in all the grinding operations described above.

For grinding down the harder rocks, it will be advisable to use corundum in place of emery, except in the first operation. It can be had in three degrees of coarseness; but the two most useful for our purpose are ‘medium’ and ‘flour’. It can be got at the dealers in dentists' sundries.

In the case of a very friable rock it is advisable to soak it thoroughly in a solution of shel lac or spirits of wine, and let it dry and harden before rubbing it down; but in many cases. such a rock can be readily examined after crumbling it by rubbing it in water with a brush, or crushing it gently with the fingers. The powder should then be dried, a small quantity laid on a slide; drop a little benzine upon it, and then a drop of the thin balsam, and cover with a cover glass. For the examination of sandstones a freshly broken surface with a strong light thrown upon it will reveal most of its structure. But it can be reduced to sand as described above, and mounted dry, (do not attempt to examine it without mounting, or the grains of sand will probably do some injury to the microscope). A flat India rubber ring fastened to a slip makes a useful cell; lay the sand in this and cover with a thin cover glass; a little balsam round the edge will hold it securely. For grinding soft rocks, such as coal, a flat piece of pumice stone may be used with advantage. I have purposely said nothing about the use of the lapidary's wheel in this paper, as my object has been to shew how rocks can be prepared for examination by the aid of the most simple and readily obtained apparatus, by any practical geologist.”

The life of Henry C. Beasley:

Henry Charles Beasley was born on March 4, 1836 in Leamington, Warwickshire. He appears to have been the only child of Henry and Mary Beasley. Father Henry worked as a “chemist”. Shortly after our microscopist’s birth, the family moved to Uxbridge, Middlesex, which was the father’s home town. The father died in 1853.

Our Henry then moved in with a maternal uncle, Noah Jones, a non-conformist minister in Little Woolton, Lancashire. The 1861 national census listed Henry’s occupation as “merchant’s clerk”. Uncle Noah died in late 1861. Henry remained with his aunt and her children. The 1871 census showed Henry there, working as a “ship broker’s clerk”. He worked as a clerk / book keeper for the remainder of his life. An obituary wrote, “Mr. Beasley was a most indefatigable and persistent worker at his favourite geological subjects, such work being his relaxation from an active commercial career.”

Beasley joined the Liverpool Geological Society in 1871. He contributed numerous articles to the Society’s Proceedings, including “On the microscopic structure of the carboniferous limestone with reference to its mode of deposition” (1878) and the above-quoted paper on how to prepare mineral specimens for the microscope. He also served as President for three years, and Secretary for eleven years.

In 1880, Henry married Sarah Elizabeth Jones, and the pair settled in Wavetree, Liverpool. They had one child, a daughter named Jessie. Henry’s job as a clerk / book keeper provided the family with a fairly comfortable life, as evidenced by their employment of a domestic housekeeper through the late 1800s and into the 1900s.

As time went by, Beasley developed a strong interest in fossilized animal trackways, and acquired a considerable collection of them.

Henry Beasley joined the Liverpool Biological Society in 1888, and the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1904. One article that I found referred to him as “F.G.S.” (Fellow of the Geological Society of London), but that appears to be a mistake.

However, in 1906, the Geological Society of London presented Henry Beasley with the Barlow-Jameson Fund Award, writing, “Mr. Beasley, The sum of Twenty-Five Pounds from the Barlow-Jameson Fund is awarded to you by the Council, in recognition of your important work on the Triassic rocks. In connexion with that work I may refer to your valuable descriptions of footprints from the Trias, in which you have abstained from burdening our fossil-lists with new names. You have travelled much on either side of the Atlantic, obtaining thereby much information concerning geological matters, more especially with reference to the Triassic rocks. I may also allude to your work on Glacial Geology, and to a suggestive paper on the water ejected from volcanoes. I hope that this award of the Council will encourage you in the further prosecution of your fruitful researches.”

The Liverpool Geological Society elected Henry Beasley as an Honorary Member in 1916, in respect of his 46 years of service to the Society.

Henry Beasley died on December 14, 1919.

Obituary from The Geological Magazine: “The late Henry C. Beasley, who died at Liverpool on December 14, 1919, at the ripe age of 83, was best known to geologists for his work in connexion with the Triassic footprints, especially those found in the Keuper beds at Storeton, Cheshire, and other quarries in the Liverpool district. He published a number of papers in the Proceedings of the Liverpool Geological Society recording his observations, and as Secretary of the British Association Committee for the Investigation of the Fauna and Flora of the Trias of the British Isles, he wrote a series of reports on the footprints for which he proposed a provisional scheme of classification. In 1906 he was awarded the proceeds of the Barlow-Jameson Fund by the Geological Society of London for his geological work in this connexion. He was Secretary of the Liverpool Geological Society from 1890 to 1900, and President for the sessions 1887-9, 1904-6, and again 1908-9, and served as President of the Liverpool Biological Society for 1901-2. His fine collection of footprints was recently purchased by Councillor C. Sydney Jones, M.A., for the Free Public Museum of Liverpool. Mr. Beasley was a most indefatigable and persistent worker at his favourite geological subjects, such work being his relaxation from an active commercial career. His unselfish character and his readiness at all times to assist any fellow-worker endeared him to all who knew him".

Memorial from the Liverpool Geological Society: “That the members of the Liverpool Geological Society desire to record their deep sense of the loss which the Society has sustained by the death of Mr. Henry Charles Bailey, whose connection with the Society extended over a period of nearly 49 years. Elected an Ordinary Member in January, 1871, he maintained an active and devoted interest in its work and affairs until prevented by the infirmities of age, serving it as secretary for seven years, and as President for three terms. His original investigations bearing upon the problems of local geology, and more particularly his study and classification of the fossil footprints of the Triassic sandstones (the results of which are, for the most part, published in a series of valuable papers in the Proceedings of the Society) have added considerably to our knowledge, and are characterized by painstaking zeal and high conscientiousness. His genial and helpful disposition will long and gratefully be remembered, and will serve as a stimulating example to those who follow him.”

A final note from the Liverpool Geological Society (1920), “It will be of interest to members to know that the unique collection of Triassic footprints, made by our member, Mr. H.C. Beasley, which have been the subject of so many papers by him, published in our Proceedings and elsewhere, has been recently acquired by the Liverpool Free Public Museum, and will thus be permanently housed. We hope that it will be suitably displayed, so that it may be easily available to students.” (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

H.C. Beasley’s “D2” type specimen, footprints of Rhynchosaurides rectipes, approximately 240,000,000 years old. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from The University of Liverpool Victoria Gallery and Museum, https://vgm.liverpool.ac.uk/exhibitions_events_tours/permanent/fossils/.

Resources

Beasley, Henry C. (1878) On the microscopic structure of the carboniferous limestone with reference to its mode of deposition, Proceedings of the Liverpool Geological Society, pages 359-361

Beasley, Henry C. (1883) On the preparation of rocks for microscopical examination (principally with reference to the sedimentary rocks), Proceedings of the Liverpool Geological Society, pages 142-147

Beasley, Henry C. (1885) A quarry at Poulton, and the relation of the glacial markings there, to others in the neighbourhood, Proceedings of the Liverpool Geological Society, page 84-93

Beasley, Henry C. (1889) The life of the English Trias (Presidential Address), Proceedings of the Liverpool Geological Society, pages 145-163

Beasley, Henry C. (1895) An attempt to classify the footprints in the New Red Sandstone of this district, Proceedings of the Liverpool Geological Society, pages 391-409

Beasley, Henry C. (1895) Notes on examples of footprints, &c., from the Trias in some provincial museums, Proceedings of the Liverpool Geological Society, pages 233-237

Beasley, Henry C. (1895) A section of the Trias recently exposed on Prenton Hill, Proceedings of the Liverpool Geological Society, pages 238-251

Beasley, Henry C. (1908) Some markings, other than footprints in the Keuper sandstones and marls, Proceedings of the Liverpool Geological Society, pages 262-275

Beasley, Henry C. (1910) Description of a group of footprints in the Storeton find of 1910, Proceedings of the Liverpool Geological Society, pages 108-115

England census and other records, accessed through ancestry.com

The Geological Magazine (1920) Henry Charles Beasley, Vol. 57, pages 94-95

Proceedings of the Geological Society of London (1906) Awarding of the Barlow-Jameson Fund Prize, page 58

Proceedings of the Liverpool Geological Society (1910) The Storeton Footprints, pages 38-40

Proceedings of the Liverpool Geological Society (1916) “Mr. H.C. Beasley, 25a Prince Alfred Road, Wavetree (for 46 years an Ordinary Member of the Society), and Prof. J.W. Gregory, D.Sc., F.R.S, of Glasgow University, were elected Honorary Members”, page v

Proceedings of the Liverpool Geological Society (1920) Tribute to Henry Charles Beasley, pages vi-vii

Report of the British Association for the Advancement of Science (1907) membership list, “1904, Beasley, H.C., 25A Price Alfred-road, Wavetree, Liverpool”

Sarjeant, William A.S. (1984) The Beasley Collection of photographs and drawings of fossil footprints and bones, and of fossil and recent sedimentary structures, The Geological Curator, Vol. 4, pages 133-138

The Scientist's International Directory (1905) “Beasley, Henry C., Prince Alfred-road, Wavertree. Geol., Triassic Footprints”, page 265

The Scientist's International Directory (1914) “Beasley, Henry C., Prince Alfred-road, Wavertree. Geol., Triassic Footprints”, page136

University of Liverpool Victoria Gallery and Museum (accessed June, 2024) Fossils, https://vgm.liverpool.ac.uk/exhibitions_events_tours/permanent/fossils/