Philip Brock, ca. 1750 - ca. 1822

John Brock, ca. 1773 - after 1802

by Brian Stevenson

last updated September, 2023

Philip Brock was relatively minor London maker of microscopes and other scientific/mathematic instruments during the last quarter of the 1700s and first quarter of the 1800s. John Brock was a London "spectacle maker" in the early 1800s, and may also have produced optical instruments such as microscopes. It is possible that Philip and John were related, but that is not certain.

However, one or both Brocks are notable for two distinctive microscope designs (Figures 1 and 2). Philip Brock undoubtedly built the instrument shown in Figure 1, based upon the engraved address. The producer of the microscope shown in Figure 2 is uncertain.

Neither Brock was listed in any street / trade directory that I have examined. This suggests that they may have primarily “worked for the trade”, that is, worked on commission for other businesses / retailers. Many other microscope makers did this. For example, James Smith, later the owner of Smith and Beck / Smith, Beck & Beck worked as an anonymous contractor for several years.

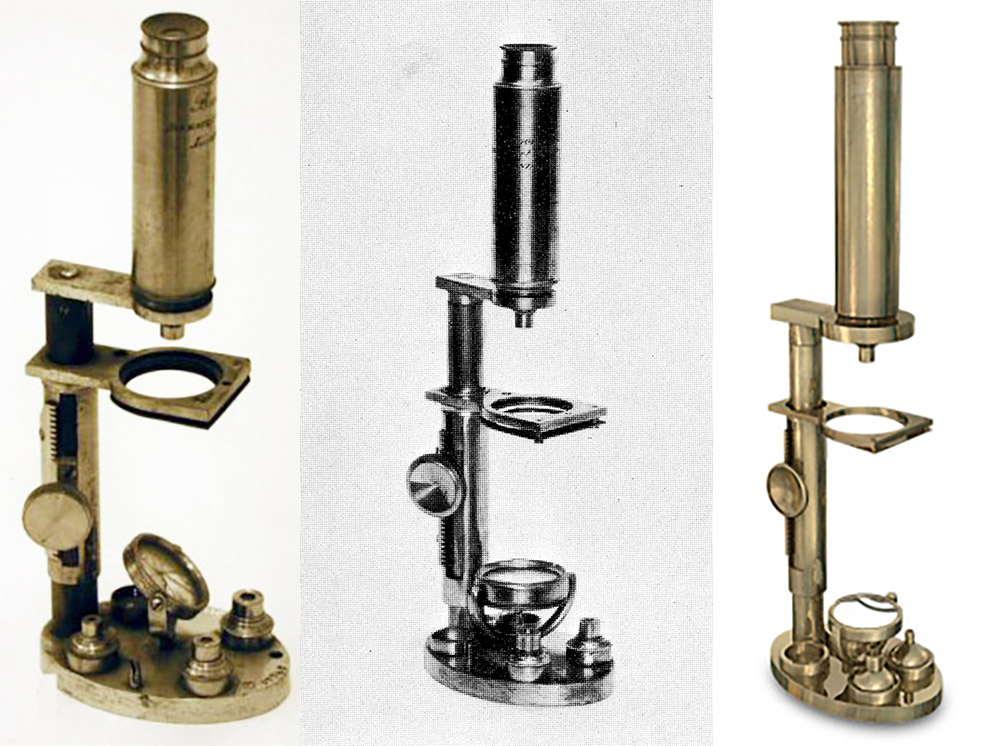

Figure 1.

(left and center) Microscope signed “Brock, No. 39 Little Bartholomew Close, London”. Philip Brock is known to have operated an optical business at that address from ca. 1790 until ca. 1798. It is a variation on Benjamin Martin’s “Universal” microscope, a design that also spawned George Adams Jr.’s “Improved Compound” and W. & S. Jones’ “Most Improved” microscopes. The cylindrical limb with internal tube and geared focus, and the mirror mounted on an attached rod, were also used by Martin / Martin & Son ca. 1780-1790 (an example of which is shown at the right). Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from auction / retail sites.

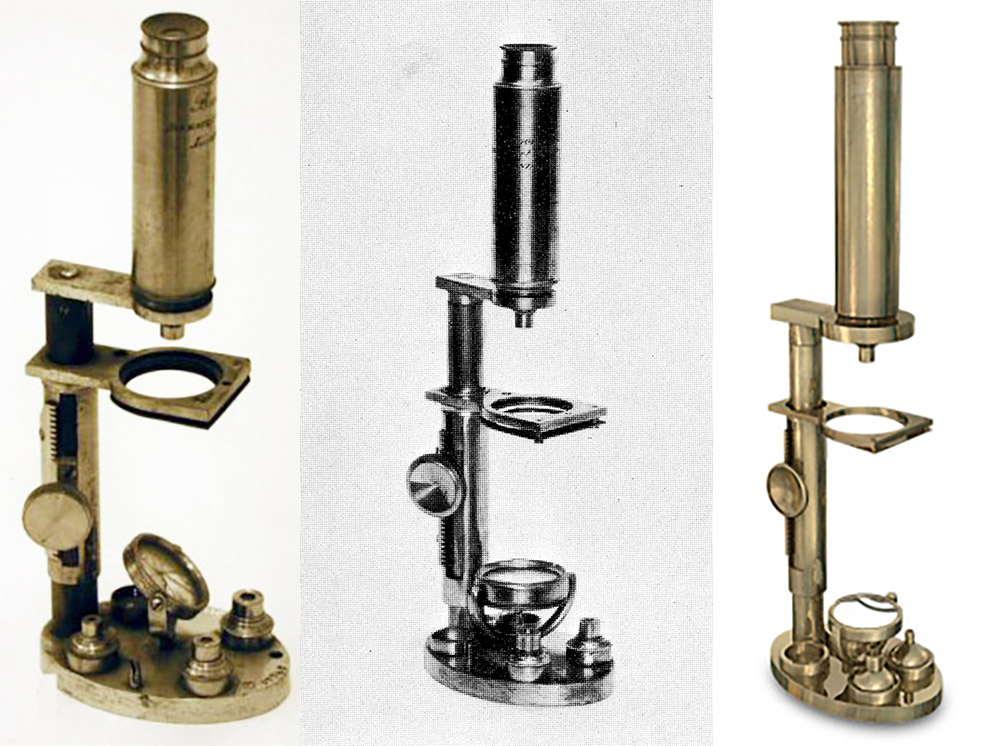

Figure 2.

(Left and Center images) Two examples of a unique microscope, signed “Brock, Invenit et Fecit, London” (“invented and made”). The general appearance resembles microscopes that were made during the early 1800s, and so may have been produced by either Philip or John Brock. The limb with geared focus that moves an internal cylinder within an external sleeve is similar to that used in the Brock microscope shown in Figure 1. The base has cups to hold four objective lenses. (Right image) An illustration of the microscope in the center panel. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from “A Catalogue of the Microscopy Collections at The Science Museum, London”, “The Billings Microscope Collection”, and https://micro.magnet.fsu.edu/primer/museum/britishfixedmirror1800.html. For an unknown reason, the authors of “The Billings Microscope Collection” suggested that Brock’s first initial might have been “G.”

Philip Brock

The earliest firm evidence that we have of Philip Brock’s life is that he was made a Freedman of the Worshipful Company of Makers of Playing Cards in 1778. It is important to note that, at that time, a craftsman’s guild did not necessarily coincide with his occupation. As additional examples, Edmund Culpeper, George Adams Sr. and Jr., and Edward Troughton were all members of the Grocers’ Company.

Philip Brock had a shop on Fetter Lane in 1778. Occupancy tax records indicate that nobody named Brock was at that location in 1776.

Also in 1778, Philip and his wife, Ann, had a baby boy, named Philip. The baby was christened at St. Andrew Holborn, which is located adjacent to Fetter Lane. Son Philip died in 1785, aged 6 years, 2 months. His death indicates that later records of “Philip Brock” were for the father.

Philip Brock had probably been living in the vicinity since ca. 1772. The parish records of St. Andrew Holborn state that Philip and Ann Brock christened their daughter, Ann, at that church in 1772. The record also describes the Brocks as being “from St. Brides”, implying that they had only recently moved into the St. Andrew Holborn parish. This also raises the likelihood that Brock’s master and/or previous employer was located in the parish of St. Brides. Brock is not listed as paying occupancy tax prior to 1778, suggesting that he was not the head of a household, and likely worked for and lived with another person.

A young man generally began his apprenticeship at around 13 years of age, and served for seven years. Apprenticeship contracts prohibited the apprentice from marrying during the time of his training. If the baby born to Philip and Ann Brock in 1772 was indeed the child of our microscopist, then Philip was at least 20 years old at the time (the baby was not noted as being illegitimate, indicating that Philip and Ann were legally married). Our man may have been the Philip Brock who married Ann Coe on February 13, 1770 at St. Botolph, Aldgate. This gives Philip Brock a birth date of ca. 1750.

Philip Brock paid occupancy taxes on the Fetter Lane shop in 1778 and 1779. The 1780 tax book records that “William Brock” occupied that site. It is not known whether the name was a clerical error, or if there was actually a man named William who was head of the household.

Philip moved to Little Bartholomew Close, probably during the spring of 1781. That date is based on nobody named "Brock" being listed in the 1881 occupancy tax records for that street, and Philip and Ann Brock having the christened a son, Joseph Thomas Brock, at St. Sepulchre on March 25, 1781. St. Sepulchre is adjacent to Little Bartholomew. Additional children were christened at St. Sepulchre during the following years.

Philip Brock took an apprentice, Richard Ives, on November 19, 1781.

The next several years’ of occupancy tax records are confusing as to the head of the household. 1783 listed “James Brook”, 1784 listed simply “Brock”, and 1785 listed “William Brock”. These could have been real people or clerical errors.

Philip Brock's name appears in the tax books from 1790 through 1798. Confirmation of his optical business at this site comes from this record: “Sherwood, John Hallett … in May, 1790 took out insurance cover of £200 which included £60 for utensils and stock in the dwelling house of Brock, an optician at 39 Little Bartholomew Close”. The Poll Book of London from 1796 listed “Brock, Philip, Card maker, Little Bartholomew Close”.

Tax records from 1798 show that Brock was still located at Little Bartholomew Close. He was not there at the time of the tax collections of 1800 or later. Brock’s location until 1817 is not yet known. His disappearance from tax records suggests that he may have lived and worked in another person's residence/shop between ca. 1798 and 1817.

A former apprentice, John Frederick Newman, became a Freedman of the Worshipful Company of Makers of Playing Cards in 1807. It is possible that Newman had been released from his apprenticeship years earlier, but opted to pay for guild membership at a later date.

Brock reemerges in the 1817 records of London occupancy taxes, living at 9 Church Row, near Aldgate. The 1816 tax book recorded a different person at that site.

On October 28, 1818, Philip Brock “Optical Instrument Maker” appeared in court as the victim of a robbery. David Lazarus, age 14, was “indicted for stealing, on the 28th of September, one mahogany case, value 12s.; one body of a microscope, value 7s. 6d.; four glasses, value 7s.; four ivory sliders and objects, value 4s.; one concave mirror, value 2s.; one plane mirror, value 2s.; one side illuminator, value 3s. 6d.; one pair of nippers and crutch, value 2s.; one pair of corn-tongs, value 6d., and one brass plate, value 1s. 6d., the goods of Philip Brock”.

Brock testified, “I am an optical instrument-maker, and live in Church-row, Aldgate . On the 28th of September I was at work at the window - the articles stated in the indictment were in a case behind me. The prisoner came in to buy a glass for a show. I said I had nobody to serve him, he said he would call in half an hour - he went round on my left hand, and went out. In about five minutes I missed the microscope and case. I informed the officer. I am certain the prisoner is the boy who came into the shop. The microscope was safe when he came in, and nobody came in after till I missed it.”

Lazarus was found guilty, and transported to Australia.

More importantly for our story, this record sheds considerable light on Brock’s business of the time. The boy stole components of a microscope, rather than an assembled instrument. Perhaps they were all in a box, awaiting assembly or collection by an intended customer? A complete microscope would have been a more logical target – did the boy not steal one because Brock did not have complete instruments on display for potential customers? Brock was working at the window, presumably because of the light. He did not have an employee to take care of the customer, and would not stop his work to wait on the boy. Brock was willing to sell a mirror (“a glass”), but only if the customer came back “in half an hour”. These support the hypothesis that Brock was not primarily a retailer.

Tax records through 1822 show Philip Brock on Church Row. The 1824 tax book did not include Brock, and another man was in that shop.

I have not found records of Philip Brock after 1822. He probably died around that time, as he would have been about 70 years old.

John Brock

In 1800, John Brock became a member of the Spectaclemakers’ Guild (Figure 3). His membership was by “redemption”, meaning that he purchased membership, rather than joined by patrimony. His father was recorded as Richard Brock, a tailor of Sherbourne (?), Devon (Figure 3). At least two boys named John were born to a Richard Brock in Devon at a date likely to have been this John, in 1773 and 1777.

The 1800 occupancy tax records show that a John Brock was located in Red Cross Square, in the parochial parish of Aldersgate Within. The 1801 tax book shows a “Joseph Brock” in that location. Was this our optician?

On July 8, 1801, John Brock, “Citizen and Spectacle Maker of London” took Sion Strickland as an apprentice.

John Brock then disappears from known records.

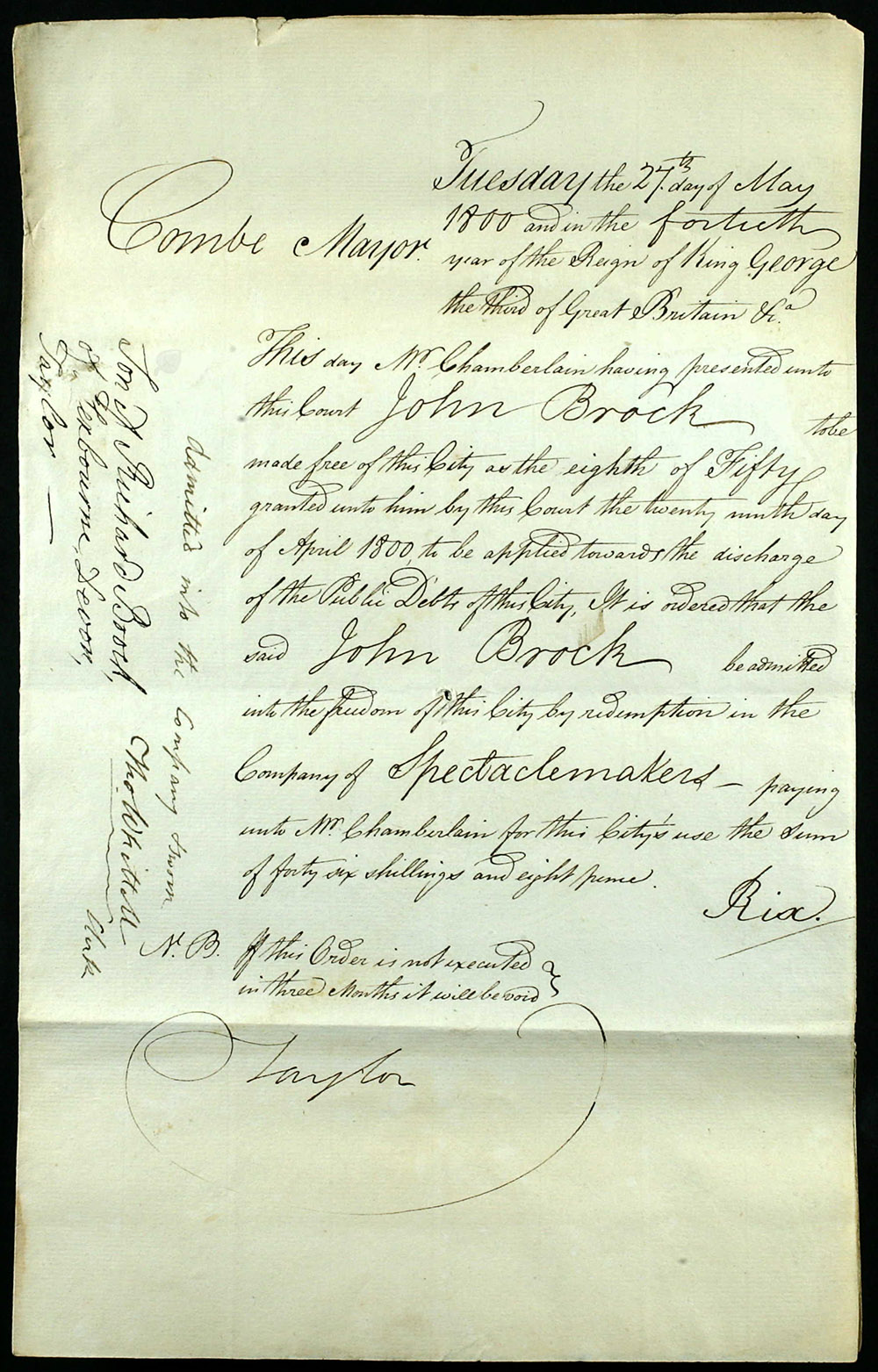

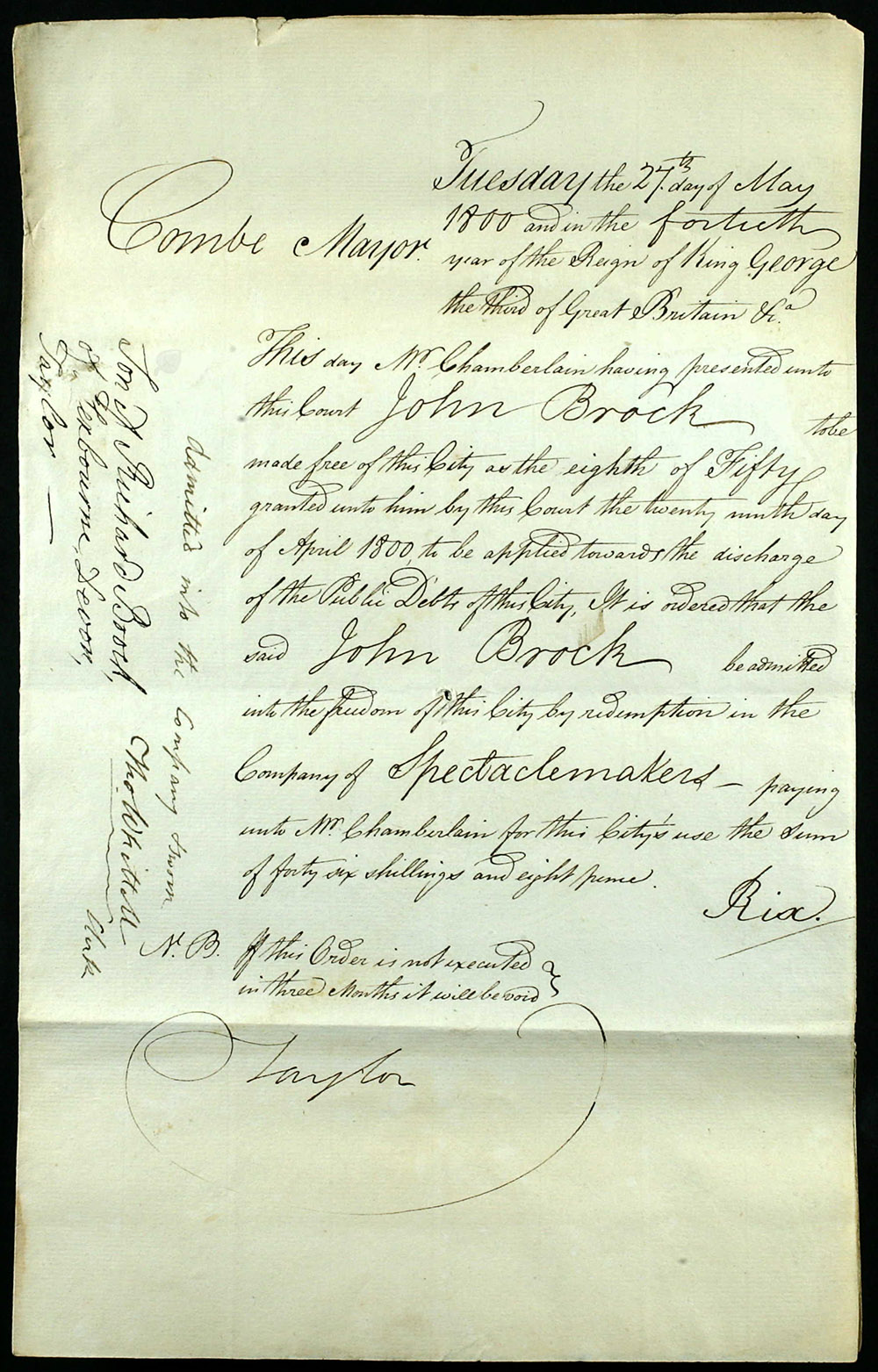

Figure 3.

John Brock became a member of the Worshipful Company of Spectacle Makers on May 27, 1800.

Acknowledgement

Thank you to Joe Zeligs for pointing out the similarities between the ca. 1790 Brock microscope and those that were made by Benjamin Martin / Martin & Son.

Resources

Bracegirdle, Brian (2005) A Catalogue of the Microscopy Collections at The Science Museum, London, Little Imp

Brown, Joyce (1979) Mathematical Instrument-Makers in the Grocers’ Company 1688-1800, Science Museum, London

Clifford, Gloria (1995) Directory of British Scientific Instrument Makers 1550-1851 (1995) Zwemmer, London, pages 38 and 199

Dictionary of English Furniture Makers 1660-1840 (1986) Edited by Geoffrey Beard and Christopher Gilbert, W.S. Maney and Son Limited, Leeds, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/dict-english-furniture-makers/s

England tax and other records, accessed through ancestry.com

https://micro.magnet.fsu.edu/primer/museum/britishfixedmirror1800.html (accessed September, 2023) British Fixed-Mirror Monocular Microscope

Hansen, James L., William A. Schrader, William R. Cowan, Joshua E. Henderson, Oscar W. Richards, Helen R. Purtle, and John A. Ey (1974) The Billings Microscope Collection, Second Edition, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, D.C., page 23, Figure 41

Kent’s Original London Directory (1823)

Lowndes’ London Directory (1786)

The Post Office London Directory (1807)

The Post Office London Directory (1817)

Proceedings of the Old Bailey (accessed September, 2023) https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?div=t18181028-90

Wakefield's Merchant and Tradesman's General Directory for London (1794)