Fredrick Reardon Brokenshire, 1842 - 1918

by Brian Stevenson

last updated October, 2016

F.R. Brokenshire appears to have taken up microscopy as a hobby during the 1880s, as questions he posed to amateur science magazines of the time were relatively basic. He was a member of the Postal Microscopical Society by the mid-1880s, and joined the Quekett Microscopical Club late in his life. I have not found any records of him publishing offers to exchange slides. Thus, Brokenshire slides that are encountered nowadays probably came from his personal collection, and may explain their relative scarcity.

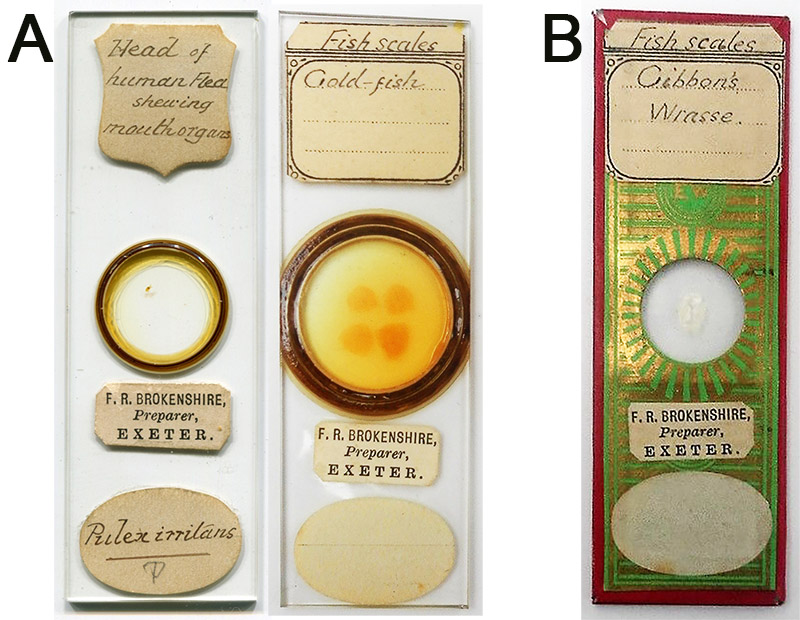

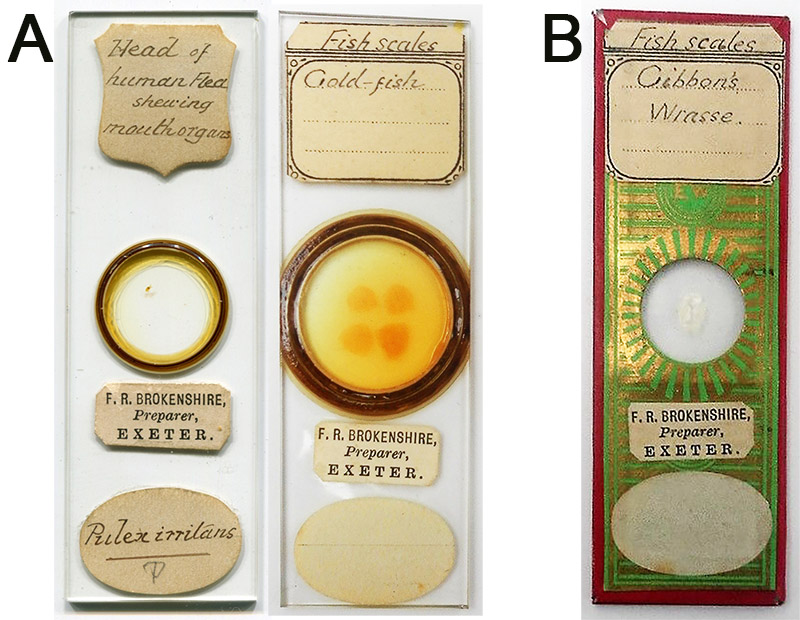

Figure 1.

Microscope slides prepared by or purchased by Frederick R. Brokenshire. It is probable that all came from his personal collection. (A) Two slides that were prepared by Brokenshire. (B) A slide of scales from Gibbon’s Wrasse, produced by Edmund Wheeler (note the maker’s initials printed on his distinctive cover paper). Brokenshire wrote in 1888 about finding numerous Gibbon’s wrasse on the beach at Dawlish, Devon, remarking that it was an uncommon visitor to English waters (see below). Brokenshire described saving a piece of a fish’s skin, and offering scales to interested readers, and may have acquired Wheeler’s professional preparation as a model from which to make his own mounts. Images of slides from the author’s collection or adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from internet auction sites.

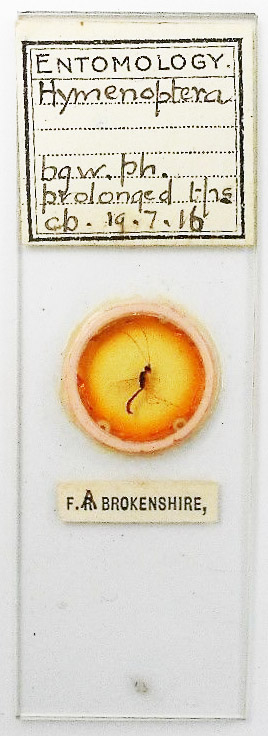

Figure 2.

“Head of human flea shewing mouthparts”, by Frederick H. Brokenshire. Photographed using a C-mounted digital SLR camera and a 10-x objective lens, with brightfield (left) and crossed polarizing filters (right).

Frederick Reardon Brokenshire was born late in the year of 1841, in Exeter, Devon, England. His middle name must have been an old family name, as his father’s name was Adolphus Reardon Brokenshire. Father Adolphus was a tailor, and mother, Sophia, made dresses. Frederick was the eldest of their three children, followed by brother Henry and sister Bessie.

Frederick Brokenshire never married. He lived with his parents and, after his father died in 1870, lived with and cared for his mother until her death in 1906.

Brokenshire worked first as a “commercial clerk - fancy trade” (1861 census) and “shopman” (1871 census). From the late 1870s onward he was a traveling salesman, representing distributors of diverse items such as lamp oil and fancy soaps. He was reasonably well-off, as every census from 1881 onward states that he employed a live-in servant.

The Journal of the Postal Microscopical Society published a letter from Brokenshire in 1885, “Replying to your invitation on p. 214 of your invaluable Journal for the current quarter to subscribers, to drop you a line in re the “Lett-Worsley-Benison” question, I have much pleasure in saying that I think your idea of a “Monthly Supplement” a capital compromise between the suggestions of these two gentlemen, and likely, if acted on, to provide many like myself with what I find to be a great desideratum - a somewhere to go with my questions, technical and otherwise; questions which I am sure would be freely answered by many subscribers when the projected medium of communication is established. I feel certain also that a series of papers devoted to common objects, where to find, how to view to best advantage, and how to permanently prepare them, would be of inestimable value. I am, etc., F.R. Brokenshire”. The letter implies that Brokenshire was a member of the P.M.S. Moreover, his comments that he was likely to ask many questions of members suggests that he was a neophyte.

In 1887, Brokenshire asked questions Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip about how to use a camera lucida with a microscope, and again to that magazine and to The English Mechanic and the World of Science on how one can calculate the magnifying powers of microscope lenses.

A letter was written to The Scientific Enquirer in 1888, on finding abundant Gibbon’s Wrasse fish on a Devon shore (See Figure 1). Comments by Brokenshire in this article indicate the enthusiasm he felt for microscopy. “The south coast of Devon has lately been visited by large numbers of a fish which, common enough in the Mediterranean, is seldom found near our shores. While at Dawlish on a recent occasion, I was struck, while walking over the beach to the rock pools, at low tide, by the frequent occurrence of a very handsome reddish-gold fish lying at my feet, which had been stranded by the ebbing tide. In shape, it was somewhat that of the fresh-water perch, and is, in consequence, as I ascertained from an intelligent old fisherman, who was ‘titivating’ his boat on the sands, popularly known as the sea-perch. He informed me that it was a very rare visitor to our seas; that, in fact, he had only known it appear in any number three or four times in his somewhat long life, and, as settling the fact of its rarity on the English coast, he added that, at the Albert Museum at Exeter, there is one of a former batch of immigrants, which arrived many years ago, carefully preserved as a curiosity. Leaving my informant, and proceeding to the rock-pools, in which an unusually low tide had left all that the micro-fisher could desire, I found here and there, left by the tide, in isolated pools, living and vigorous specimens of the same lovely fish, suggesting, at first sight, the gold-fish of our window aquaria and garden-ponds, but larger and squarer in shape. The name which heads this paper is, so far as I can ascertain, correct, but I cannot find any mention of this particular species in any work of reference in my possession. Why these denizens of warmer seas should visit us at all I am not going to speculate on, and certainly not why they should select such an inclement season as the present; but, at the same time, any information on this point would be interesting. I secured a piece of the skin, having a microscopist’s eye to chances, and find that it is densely crowded with scales that are very peculiar certainly, and, in my experience, unique. The scale itself is entire - i.e., unbroken in its outline. It would, therefore, I suppose, be correctly described as cydoid, but at first sight it appears more decidedly comb-like than any scale I have ever met with. This appearance is due to the presence of a number of spines (forty to fifty) proceeding from the free half of the scale, inclined only very slightly downwards and directed backwards, and as each spine is about one-third the longest diameter of the scale itself, they must, without overlapping, form a perfect chevaux-de-frise armature, effectually protecting its owner from all enemies not very superior in size and courage. Those of my readers who remember the tortoise-shell head-comb formerly worn by ladies in their coiled-up back hair have only to imagine the teeth of that same comb springing from its plane instead of from its margin, and they have the scale of the sea-perch “to a t.” Any reader who has been at all interested in this bit of gossip, and would like to have one or two of the scales to mount for his micro-cabinet, will be welcome to them as far as my stock goes, if he will send a stamped, directed envelope to F.R. Brokenshire, 24 Oxford Terrace, Exeter”.

Typical of an enthusiast, Frederick’s collection of self-made and purchase microscope slides grew, such that he published this request in Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip in 1893, “Wanted, vol. i . of Kuchenmeister's ‘Manual of Parasites’, published by the Sydenham Society, 1856; also cabinet for micro. objects, with trays for 500 or 1000. - F.R. Brokenshire, 24 Oxford Terrace, Exeter”.

In 1901, Brokenshire queried of Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip, “Mites In Microscopic Slide - I have a slide of a portion of the polypary of a Californian zoophyte (Membranipora tuberculata) mounted as an opaque object for toplight. It is in a cell which is securely sealed by an ornamental paper with an opening to show the object, but otherwise covering the 3x1 glass slide thoroughly and effectually, the object being hermetically sealed. I have no record of the preparer, except that it is not my own work. The slide, has been in my cabinet for certainly not less than ten years, and, until a day or two since, for a very long time I have not seen it under the microscope. On this occasion I had it under the 2-inch and brilliantly lighted by the side-reflector, when some moving object in the cell caught my attention. This moving, living object proved to be a mite, which was active and vigorous, and, so far as I could examine it, resembled the cheese mite (Tyroglyphus domesticus). It was not alone, for I quickly discovered another, equally lively, and on looking closely I found two exuviae and what looked like portions of others. The object in which these mites have been carrying on their life-histories is about 3-10th of an inch square, and presents on the surface 360 thecae, or cells - a sufficiently big world for two or three organisms so tiny - but whence came they, and whence their supply of oxygen and food? These are questions which puzzle me. - F.R. Brokenshire, Exeter”. The magazine editors responded, “If we understand our correspondent aright, the cell is a dry one, and the cover-glass is held in place only by the paper covering the slide. The cell would therefore not be hermetically sealed. The mite referred to may be Tyroglyphus entomophagus or Oheyletus eruditus, the book-mite, both of which are not uncommon unfortunately in museums and collections, where they feed upon the specimens, causing much havock. Cheyletus can be distinguished by its large raptorial palpi, of which a good drawing appeared in Mr. Allen's ‘Journal of Microscopy’, 1893, p. 100. There is a drawing in the ‘Micrographic Dictionary’, but it is not accurate”.

The Brokenshires lived at 24 Oxford Terrace, Exeter, until at least 1893. The 1901 census recorded their home as 53 Oxford Road. By 1911, Brokenshire lived at 7 Hillsborough Avenue, Exeter, and remained there until his death.

Frederick’s mother, Sophia, died at their Exeter home in 1906. The 1911 census listed Frederick as being a 69 year-old “retired commercial traveller”. His niece and great-niece were with him on that census day, possibly a visit, since her husband was at their home in Barnstaple, Devon. The household also included a domestic servant.

Frederick Brokenshire died on March 10, 1918. His probate stated, “Brokenshire Frederick Reardon of 7 Hillsborough-avenue Pennsylvania Exeter gentleman died 10 March 1918 Probate Exeter 19 March to Frederick Adolphus Brokenshire schoolmaster and William Alfred Milton stockbroker. Effects £1723 9s 3d”.

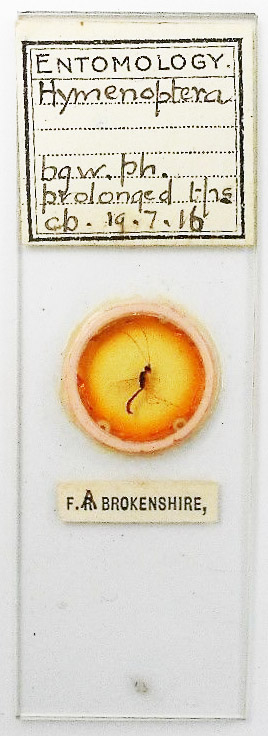

Frederick Adolphus Brokenshire (1866-1957) was a son of F.R. Brokenshire’s brother, Henry, and husband to the niece who was with F.R. during the 1911 census. Microscope slides are seen on occasion that bear the a label with F.R. Brokenshire’s name, and the “R” overwritten with “A”, suggesting that it was prepared by F.A. Brokenshire, using a label inherited from his uncle (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

A slide, dated 1916, of a hymenoptera species, possibly a parasitic wasp. The maker’s name label is one of F.R. Brokenshire’s, with the ”R” overwritten with an “A”, to indicate preparation/ownership by his nephew, Frederick Augustus Brokenshire. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Resources

Bracegirdle, Brian (1998) Microscopical Mounts and Mounters, Quekett Microscopical Club, London, page 17

Brokenshire, F.R. (1885) Letter to the editor, The Journal of the Postal Microscopical Society, Vol. 4, page 288

Brokenshire, F.R. (1887) Microscopic queries, Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip, Vol. 23, pages 90-91

Brokenshire, F.R. (1887) To measure magnifying power of microscope objectives, English Mechanic and the World of Science, Vol. 45, page 392

Brokenshire, F.R. (1887) Measurement of magnifying power of micro-objectives, English Mechanic and the World of Science, Vol. 45, page 437

Brokenshire, F.R. (1888) Gibbon’s wrasse, Scientific Enquirer, Vol. 3, pages 102-103

Brokenshire, F.R. (1888) Mites in microscope slide, Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip, reprinted in The American Monthly Microscopical Journal, Vol. 22, pages 229-230

Bryan, G.H. (1887) Camera lucida (response to query by F.R. Brokenshire), Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip, Vol. 23, page 164

England census, birth, and death records, accessed through ancestry.com

Gill, Richard (1887) Camera lucida (response to query by F.R. Brokenshire), Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip, Vol. 23, page 116

Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip (1887) Exchange offers from F.R. Brokenshire, Vol. 23, page 24

Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip (1893) Exchange offers from F.R. Brokenshire, Vol. 29, page 96

History, Gazetteer and Directory of the County of Devon (1879) “Brokenshire Frederick, traveller, 24 Oxford terrace”, W. White, Sheffield, page 403

Journal of the Quekett Microscopical Club (1914) Members: “Nov. 24, 1914. Brokenshire, Frederick Reardon 7, Hillsboro' Avenue, Pennsylvania, Exeter”

Probate of Frederick Reardon Brokenshire (1918) accessed through ancestry.com