Figure 1. A microscope slide that was prepared by Albert P. Brown ca. 1880s.

Albert P. Brown, 1840 - 1892

by Brian Stevenson

last updated December, 2024

Located in Camden, New Jersey, across the river from Philadelphia, Albert Brown was a pharmacist and a semi-professional microscopist. An obituary summed this up, “In his busy career he found time to continue his studies, which soon led him into the special branch of microscopy. By thoroughly mastering this subject, he soon became recognized as an expert and was frequently called upon to testify in medico-legal cases. His services in this line drew attention to his store, and as a result he became a successful pharmacist, chemist and microscopist”. For many years, Brown taught microscopy at his alma mater, the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy.

Brown was a leading force in the establishment of the Camden Microscopical Society in 1878, and served as President and in other offices. Another obituary wrote that “He devoted much of his leisure time to work with the microscope and to the photographing of microscopical objects, his productions being characterized by scrupulous accuracy and attractive neatness”. I did not find evidence of Brown selling his microscope slides, suggesting that existing slides came from his personal collection or from exchanges with colleagues.

Please note that there was another A.P. Brown who was an active microscopist in the Philadelphia area at the same time as Albert. Amos P. Brown (1864-1917) was a Professor of Mineralogy and Geology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Possibly to avoid confusion, Amos Brown used microscope slide labels that were imprinted with his full first name, “Amos P. Brown”.

Figure 1.

A microscope slide that was prepared by Albert P. Brown ca. 1880s.

Figure 2.

Larvae of Pulex felis (the cat flea), prepared ca. 1880s by Albert Brown (see Figure 1). Imaged with a 3.5x objective lens, transmitted light, and C-mounted digital SLR camera on a Leitz Ortholux II microscope.

Figure 3.

An 1879 offer from Albert P. Brown to exchange microscope slides. From “The American Journal of Microscopy and Popular Science”.

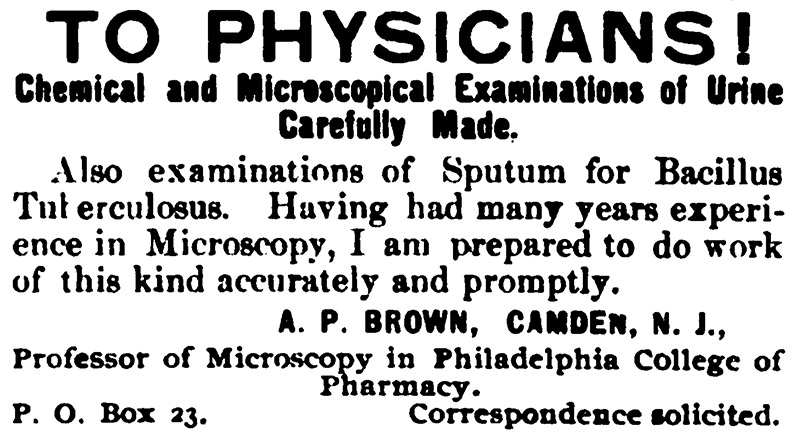

Figure 4.

Albert P. Brown served as a diagnostic microscopist for area physicians throughout his career as a pharmacist. It is ironic to note that this 1891 advertisement lists examination of sputum for the agent of tuberculosis, which claimed his life in early 1892. From “The Microscope”.

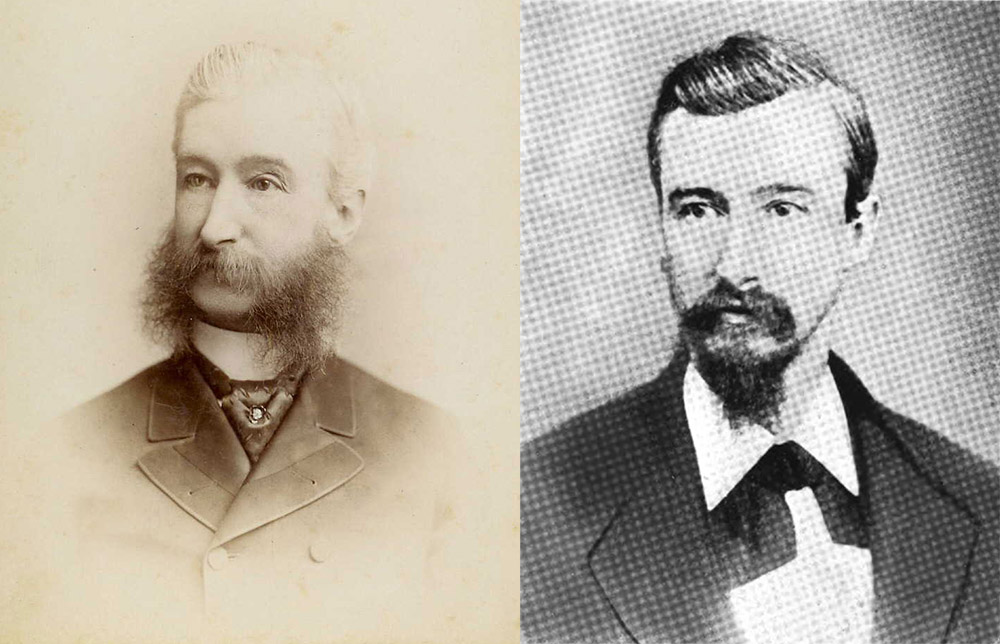

Figure 5.

Two photographs of Albert P. Brown. Left, a cdv from www.ancestry.com/mediaui-viewer/tree/9605242/person/140059456827/media/8fc57bbb-965d-4c03-b8b3-67ae8fd9b775, which was also shown in Brown’s 1892 obituary in “The Western Druggist”. Right, from “The First Century of the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy: 1821-1921”.

Albert P. Brown was born during 1840 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, a son of John T. and Mary (nee Cummings) Brown. Census records indicate at least one older sibling, Henry, and a likelihood of three additional older siblings. I did not find historical records that spelled out Brown’s middle name, although an entry in ancestry.com suggests “Paul”. The 1850 census listed father John’s occupation as “brush maker”, while the 1860 census and his death record list him as being a “janitor”.

After attending public schools, Brown worked as an apprentice with pharmacist William B. Webb in Philadelphia, and attending classes at the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy. Brown graduated in 1862, then opened a shop at 501 Federal Street, in nearby Camden, New Jersey. The shop was also the family home, and he remained at that site throughout the remainder of his life.

Around 1861, Albert married Annie R. Fenton. They had two children, Amanda and Walter. It appears that Amanda died young. Business was relatively good, such that the family was recorded as employing a domestic servant in 1870.

Brown became a member of the American Pharmaceutical Association ca. 1870. He also served as an officer of the State Pharmaceutical Association, being President in 1885 and Secretary from 1876 to 1884. In 1873, he joined the Board of Trustees of the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy.

During Brown’s time, pharmacists were expected to identify powders and extracts of botanicals that were used in formulating medicines. A microscope was thus a powerful tool for a skilled pharmacist. This was probably the major driving factor for Albert Brown developing proficiency with the microscope.

For example, in 1879, Brown reported, “I would particularly call the attention of druggists to the use of the microscope in the store. It is very important. As an illustration, I may mention, that I bought some powdered extract of licorice, a short time ago, and my clerk used it in making Brown mixture; but he reported to me that something was the matter-the mixture did not look right. Upon putting some of this powdered extract of licorice under the microscope the explanation was very evident - it was largely adulterated with starch”.

In addition to his pharmaceutical work, Brown served as a diagnostic microscopist to area physicians. He stated in 1879, “In regard to the analysis of urine by the druggist, I think it can be very properly done, both chemical and microscopical, and I have made it a special study for some six years. We have about forty physicians in Camden, and I believe I make analysis for all of them”.

Brown and a few colleagues formed the Camden Microscopical Society during 1878. The group met in “the upper room of the Camden City Dispensary”, which was “furnished for the purposes of the society, and cases containing an almost complete herbarium of the flora and collection of the minerals found in New Jersey”. Brown served as the Society’s first President.

In 1879, Albert Brown developed an adhesive/sealant for use in preparing microscope slides, which he then distributed under the name “Brown’s cement”. This was described in The American Journal of Microscopy and Popular Science as making “an elegant finish for microscopic slides. It is perfectly transparent; will not crack-and there is no danger of it running in and spoiling the specimen. If it becomes too thick to flow freely, add a few drops of benzole”. It quickly became a preferred mounting ingredient throughout the world. According to the Journal of the Royal Microscopical Society, the recipe consisted of “Pure gum rubber, 20 grains; carbon disulphide, a sufficient quantity; shellac, 2 oz.; alcohol, 8 oz. Dissolve the rubber in the smallest possible amount of carbon disulphide, add this slowly to alcohol, avoiding clots; add powdered shellac and place the bottle in boiling water until the shellac is dissolved and no more smell of carbon disulphide is given off”.

Edward Ward, a supplier of microscope slides and preparation materials in Manchester, England, began selling “Brown cement” in 1879. Curiously, Ward’s later advertisements claimed that he first described the adhesive in “a paper read before the Manchester Science Association on Jan. 26, 1880” (Figure 6). It appears that Ward’s cement was the same as A.P. Brown’s. Primary evidence lies in the name, since Brown cement is colorless. Presumably, Ward and Brown had an agreement, otherwise Ward would have used a different name for his material.

Also in 1879, Brown was elected as a member of the American Microscopical Society.

During the spring of 1882, the Board of Trustees of the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy appointed a committee “to purchase microscopes, and to form a Class in Microscopy”, chaired by Albert Brown. That summer, “after visiting several well-known manufacturers of microscopes”, they authorized purchases from Philadelphia manufacturer Joseph Zentmayer that included “1 Student stand, complete” for $36, and “1/2 dozen botanical dissectors” for $12 each. The committee later “concluded that the dissecting microscopes would not be of much use in teaching practical microscopy, and concluded to ask Mr. Zentmayer to exchange them for the ‘student’ stand. This would incur an additional expense of about $100.00”. The Board then appointed Brown as “Instructor in Microscopy for the session 1882 and 1883”. He was to be paid “as a compensation for his services, the sum of $5.00 for each student”. Brown remained in that teaching position for many years, which accounts for him often being referred to as “Professor”.

In 1883, Brown was elected to the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Pharmacists of the period were frequently called upon to assess purity of botanical and other powders, due to their skills with the microscope. Starch powders were often scrutinized, both the determine the source and to identify adulterants. Starch granules from different plants vary in size and structure, and a skilled microscopist can differentiate them. This requires reference materials, so pharmacists often purchased sets of reference slides, or prepared their own from known sources.

Brown wrote in 1891 that, “Having occasion to mount a variety of starches for examination under the microscope, I have been looking for a suitable medium that would best show the structure and at the same time preserve the specimen. The students of the class of Microscopy at the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy are desirous of preserving the different starches that are given to them for examination during the course; but until recently I have not been able to give them, for mounting of starches, pollens, and similar vegetable substances, a medium that would have the advantage of showing the structure of the specimen after it had been finished and preserved for future reference. Balsam of fir makes starches too transparent. Glycerin is good, but it is almost impossible to find a cement that would hold it on account of its solvent properties. Carbolic acid and water in time dry out. Cosmoline has been recommended, but it is too greasy and it has the same fault as glycerin; it is almost impossible to find a cement that will hold it. A short time ago Mr. Charles Bullock spoke to me of a new medium he had been using to mount vegetable tissues; it struck me as being the very article for mounting starches in. I prepared some and found it to answer the purpose admirably”. Brown’s recipe consisted of gum Arabic, glycerine, thymol, and distilled water.

To mount starches or pollens a clean slide is breathed on and then dusted over with the starch or pollen to be mounted; the surplus is removed by gently tapping the slide against any hard substance—a table, for instance. Enough of the starch will adhere to the slide and will be nicely distributed over the field. A drop of the mounting medium is now placed on the slide carefully and the cover placed over it. If there are any air-bubbles in the mounting medium when placed on the slide they should be carefully picked out with a mounting needle. If the medium is kept in a compressible tube there is not much danger of air-bubbles on squeezing out a drop; or if there are any, they will be on the surface, and can be readily removed with a mounting needle. The slide can be finished immediately by running a ring of any kind of cement around the edges of the cover-glass, and the mount is permanent.

The medium can be colored blue by adding a small quantity of aniline blue, although it is not necessary, as the structure of the starches can be plainly seen. They should be examined by central and oblique illumination and with the polariscope to give the student interested in this subject an idea of the beauty of starches and pollens”.

Brown’s interest in botanical subjects featured investigations with crossed polarizing filters. That method results in views that are both scientifically significant and visually interesting. To the latter point, Brown provided the following slide to a circulating collection of the American Postal Microscopical Club in 1892: “a preparation of the epidermis of garlic bulb, simply mounted by soaking half an hour in turpentine and then transferred to balsam, and sealed by Brown's rubber cement. The prismatic plant crystals so common in all plants of the onion family, are well shown here, making a most beautiful polariscope object”.

Albert P. Brown died on April 19, 1892, from “laryngeal tuberculosis consecutive to an attack of epidemic influenza”.

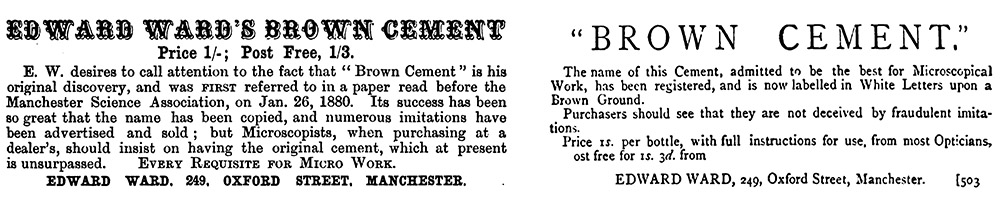

Figure 6.

Advertisements for “Brown cement” from Edward Ward, of Manchester, England. Ward claimed to have first described Brown cement in early 1880, even though he advertised its sale in the spring of 1879. Albert P. Ward announced production of his cement in 1879. That, and the use of the name “Brown” for the colorless adhesive, implies that Ward and Brown had a manufacturing agreement. From “The Journal of the Royal Microscopical Society”, 1884 (left), and “Nature”, 1886 (right).

Resources

American Druggist (1892) Memorial of Albert P. Brown, Vol. 21, page 141

The American Journal of Microscopy and Popular Science (1879) Exchange offers from A.P. Brown, Vol. 4, pages 48, 772, 188, and 232

The American Journal of Microscopy and Popular Science (1880) A new cement, Vol. 5, page 115

The American Journal of Microscopy and Popular Science (1880) “Some time ago we received a bottle of a rubber cement from Mr. A.P. Brown, of Camden, N.J. Since that time we observed that Mr. Brown has prepared this cement for sale, and from what use we have made of it, we do not hesitate to recommend it. It is transparent, does not crack, and is not likely to run under the cover", Vol. 5, page 119

American Journal of Pharmacy (1862) Catalogue of the class of the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy, Vol. 34, page 95

Annual Report of the Alumni Association of the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy (1883) pages 35, 40-41, and 42

Brown, A.P. (1891) A new medium for mounting starches and pollens, The American Monthly Microscopical Journal, Vol. 12, pages 229-230

England, Joseph Winters (1922) Albert P. Brown, The First Century of the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy: 1821-1921, Philadelphia College of Pharmacy and Science, Philadelphia, pages 384-385 and 472

Godfrey, E.L.B. (1896) The Camden Microscopical Society, History of the Medical Profession of Camden County, N.J., F.A. Davis, Philadelphia, page 146

Hardwicke's Science-Gossip (1879) Advertisement from Edward Ward, Vol. 15, April issue, page xxxv

Journal of the Royal Microscopical Society (1884) Advertisements for Edward Ward’s Brown cement, numerous issues

Journal of the Royal Microscopical Society (1891) Brown cement, page 692

The Microscope (1891) Advertisement from A.P. Brown, Vol. 11, Advertising sections of multiple issues

Munro, H. (1881) Finishing micro-slides, Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip, Vol. 17, page 16

The Naturalists’ Directory (1880) “Brown, Albert P., Ph.D., 501 Federal St., Camden. Chem., Ent. C. Ex. microscopic specimens”, S.E. Cassino, Boston, page 221

Nature (1886) Advertisements for Edward Ward’s Brown cement, numerous issues

Proceedings of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (1891) Members, Vol. 40, page xxxvi

Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the New Jersey Pharmaceutical Association (1879) page 28

Prowell, George Reeser (1886) The Microscopical Society of Camden, The History of Camden County, New Jersey, L.J. Richards, Philadelphia, page 339

Sylvester, W.H. (1892) Notes on the Postal Club, The Observer, pages 363-364

Transactions of the American Microscopical Society (1890) Members, page 257

USA census and other records, accessed through ancestry.com

Ward, R.H. (1892) Seventeenth Annual Report of the American Postal Microscopical Club, The Microscope, Vol. 12, pages 185-186

Western Druggist (1892) Memorial of Albert P. Brown, Vol. 14, page 202