Figure 1. Dry-mount of fossilized nummulites (a type of foraminifera) from carboniferous limestone, prepared by Henry Crowther. This example is not dated, but the style suggests production ca. 1880-1900.

Henry Crowther, 1848 - 1937

by Brian Stevenson

last updated August, 2024

Henry Crowther was a museum curator and teacher, spending most of his life in Leeds, Yorkshire. He was active in numerous scientific societies, including the Royal Microscopical Society, the Zoological Society of London, the Conchological Society, the Leeds Naturalists’ Club and Scientific Association, the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society, Yorkshire Geological Society, and the Yorkshire Naturalists' Union.

Although mentioned in Brian Bracegirdle’s Microscopical Mounts and Mounters for “mainly histological preparations", Crowther mounted a variety of objects, such as the fossilized nummulites in Figure 1. His greatest scientific interest was conchology, that is, the study of snails. Crowther’s microscope slides probably came from his personal collection, or from exchanges with friends.

Figure 1.

Dry-mount of fossilized nummulites (a type of foraminifera) from carboniferous limestone, prepared by Henry Crowther. This example is not dated, but the style suggests production ca. 1880-1900.

Figure 2.

Henry Crowther with his microscope, 1923. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://cypriotartleeds.wordpress.com/2012/10/31/henry-crowthers-lantern-slides/

Figure 3.

Although Henry Crowther is not known to have advertised to exchange microscope slides or specimens, he did pursue such avenues to expand his collection of snail shells. From “Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip”, 1877.

Henry Crowther was born on June 30, 1848, in Leeds, Yorkshire. He was the third child of John and Maria. At that time, father John owned a grocery shop on East Street. Maria died a year after Henry’s birth, when only 40 years old.

During his early 20s, Henry became an active member of the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society, being elected Assistant Secretary when only 23 years old. A few years later, in 1876, he was appointed Assistant Curator of the Society’s museum.

Also in 1876, Henry Crowther and three other snail enthusiasts founded the Conchological Club of Leeds. This group was later renamed as the Conchological Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Throughout his life, Crowther wrote authoritatively on snails and other mollusks.

Henry married Martha Jane Clark during the summer of 1881. They had three daughters, the second of whom, Violet, also became a museum curator.

Henry had also developed an appreciation for the microscope. In 1883, he and a colleague wrote a letter to the popular magazine Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip, proposing formation of a new group for the sharing of microscope slides:

“It has occurred to the undersigned that much mutual good might be effected if a small circle of really ardent workers could be formed for promoting the study of microscopy, amongst whom slides would circulate and general ideas become common property, something after the style of the Postal Microscopical Society, but with less routine, which might be put briefly thus: No fees, no secretary, no journal, no annual meeting; if at any time any subject were thought sufficiently good to bring before the public, the same to be done through the medium of your publication. We do not desire to have a large and cumbersome circle, and we do not propose to dignify it with the name of club, but what we desire is, a small body of really earnest workers.

It should consist, at first, of at least two members, each of whom make the following subjects their study entomology, biology, botany, geology, mineralogy, or chemistry; subsequently special branches might be added if collectively thought advisable. If the above idea commends itself to you, would you kindly aid us in forming such a circle by a short note in Science-Gossip, allowing these few remarks to be the leading feature? Mr. Crowther or myself would be glad to receive the names and addresses of such as would like to assist, and if they would mention the special department they are interested in, it would aid in establishing the circle which is intended solely for mutual good.

- W. H. Harris, 44, Partridge Row, Cardiff; Henry Crowther, Beeston Hill, Leeds.”

In 1888, Henry took a new job with the Royal Institution of Cornwall, in Truro. The Institution’s Journal announced, “In the appointment of a new Curator, the choice of the Council fell upon Mr. Henry Crowther, formerly of the Leeds Museum and of the Yorkshire Geological Society. He entered on his duties in October. Being a specialist in biology, conchology, geology, and microscopic science, and having had a special training in the newer methods of museum arrangements, it is hoped that the many treasures in our Museum in his charge, will be brought into that prominence which they deserve. As a science teacher and lecturer, Mr. Crowther is known in Yorkshire and Lancashire. The members and friends of our Institution will have the benefit of his experience, and considering that the city of Truro is fast becoming the educational centre of Cornwall, the Institution is fortunate in having secured the services of a Curator who will be able to place its collections on a level with modern requirements.”

Henry Crowther became a Fellow of the Royal Microscopical Society in 1891.

The Crowther family moved back to Leeds in 1893, as announced by The Conchologist, “Mr. Henry Crowther, late Curator of the Museum of the Royal Institution of Cornwall, Truro, and well known to all Yorkshire conchologists, has lately been appointed to the Curatorship of the Museum of the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society.” He retained that position until he retired in 1928, at age 80.

Crowther took his position very seriously, improving displays and implementing novel techniques to arouse enthusiasm in visitors. In 1905, he wrote “The Museum as a Teacher of Nature-Study”, with ideas such as, “Last year I spaced a case out for a collection of local insects, and issued by the help of the Leeds and District Teachers' Association an outline of insect classification to some 15,000 children and over 1,000 teachers. The type museum case with its contents of local insects excited much interest amongst the scholars visiting the museum, which I found was chiefly based on experience and recognition of the specimens. Such a case filled up by contributions from the school children themselves could not fail to interest other children and develop personality. Circulating cases prove that town museums have found an opening for teaching nature knowledge.”

He also gave numerous talks at the Museum, writing:

“It was easy to pass to lecturing on the general objects and to institute a series of Christmas lectures, with a display of specially-arranged objects in a room, for visitors. At the Leeds Museum a series of three lectures is delivered at 3 p.m. on the Wednesdays following Christmas Day. We average an attendance of over one thousand persons for the series, each visitor paying a small fee for admission. The lecture always centres round a selection of objects taken from the general collections in the museum, such as nests and eggs of birds, birds, mammals of various kinds, fossils, shells, and minerals or ethnological specimens. The slides used in the lectures are from the real objects lectured upon. The lecture is one hour in length, the inspection about an hour and a quarter.

I tried a series of evening lectures and our hall was crowded out each night, but the men were wishful, owing to lateness of hour, to get home at the close of the lectures, hence the after examination was not so successful.

As a result of the museum lectures, the local branch of the Leeds and District Teachers' Association approached me four years ago to ask if I would give demonstrations to batches of 20 to 30 school children from the higher sections of the elementary schools of Leeds, but feeling - and I know I am joining issue with many curators that such teaching is too restricted, too class like to expect curators to do, and that individual teachers are here so disposing of the curator's time that soon he would not have any to spare, I declined, but suggested that a special lecture should be given on a fixed day or days each week to a batch of say 300 children. I promised to write a lecture syllabus for the children's use giving outline of lecture, and notes on objects to be seen in the museum rooms which would illustrate it.

The museum committee of the teachers' association took up the subject keenly … A preliminary lecture was given to nearly five hundred teachers, who in their turn took the lessons to the schools, paid private visits to the museum, explained the syllabus of lecture, and distributed to each child a copy. I cannot pretend to explain to you all the minutiae of this great scheme by which 47,000 children have been sent to one museum within four years, how these come week by week with the regularity of a clock, gathered from points ten miles apart, and yet meeting within a few minutes of each other at the lecture theatre, and how the work grew till the city paid all costs. A lecture is given first: it allows of rest after the walk. The slides used in the lecture are from the real objects, which are also described in the syllabus Later the children perambulate the nine rooms, in charge of the same number of teachers, each batch staying in its allotted room till a bell rings, and then changing. Special lecture, special slides, special objects, special superintendence, special preparation before coming, special syllabus, and a special essay to be written next day, of which examples are sent to me. The lectures must be on big groups of objects, because examples must be displayed in all the rooms. We have had ‘Romance of a Museum’, ‘Marvels of Bird-life’, ‘Wonders of Insect-life’, and this year ‘Wonders of Animal-life: Mammals’. We shall begin again with the museum lecture next year, because no child remains three or four years in the higher sections in an elementary school. We have here, then, a successful means of conveying what is meant by nature knowledge. We may explain the nature of the markings on a giraffe, a leopard, and a tiger; the complexity of the hand, the hatching of a butterfly, the interlocking of a feather, what we mean by attack and defence among animals, and how a bird differs from a reptile. We are merely dealing with a larger audience than the field naturalist, and with more material. Museums are specially adapted for this class of teaching, which is direct and effective.

Visitors from places outside Leeds join in this scheme, coming in special trains to learn and see. From this again has arisen a desire by the teachers to have special lectures on nature study. Over six hundred tickets were sold for a course I gave of five lectures, and excursions in the country followed these. Under these schemes over 4,000 known visits have been made by teachers to our museum within four years”.

In addition to presenting at the Leeds Museum, Crowther “took his show on the road”, speaking at venues throughout the country. A flier for his lectures is shown in Figure 4.

Crowther’s interests in the public and expertise with the microscope led to collaborative studies of coal dust and mine explosions with mining engineers such as Sir William E. Garforth (1845-1921). Garforth’s 1912 Presidential Address to the Institute of Mining Engineers included, “In endeavouring to obtain a preventive against the danger of coal-dust, it was necessary that information from every available source should be obtained. The answer to these and other questions respecting invisible matter could only be obtained by a microscopical examination. Fortunately, I had collected from the underground roads, after the 1886 disaster, samples of the dust over which the explosion had been known to traverse, as also from other portions of the mine. Since 1887 I have, in conjunction with Mr. H. Crowther, of the Museum, Leeds, been engaged on the microscopical examination of coal-dust, including the dusts obtained from the gallery experiments of 1908-1909-1910. The Coal-dust Committee have to thank Mr. Crowther for this and other valuable work accomplished by him during the coal-dust investigations.”

Crowther worked his coal dust studies into one of his many public lectures and lantern shows. This included a talk on April 20, 1921 to the Royal Microscopical Society, “A coal-dust explosion as seen through the microscope”.

Martha Crowther died on November 24, 1928, the same time that Henry retired from his museum curator position He passed away on November 29, 1937.

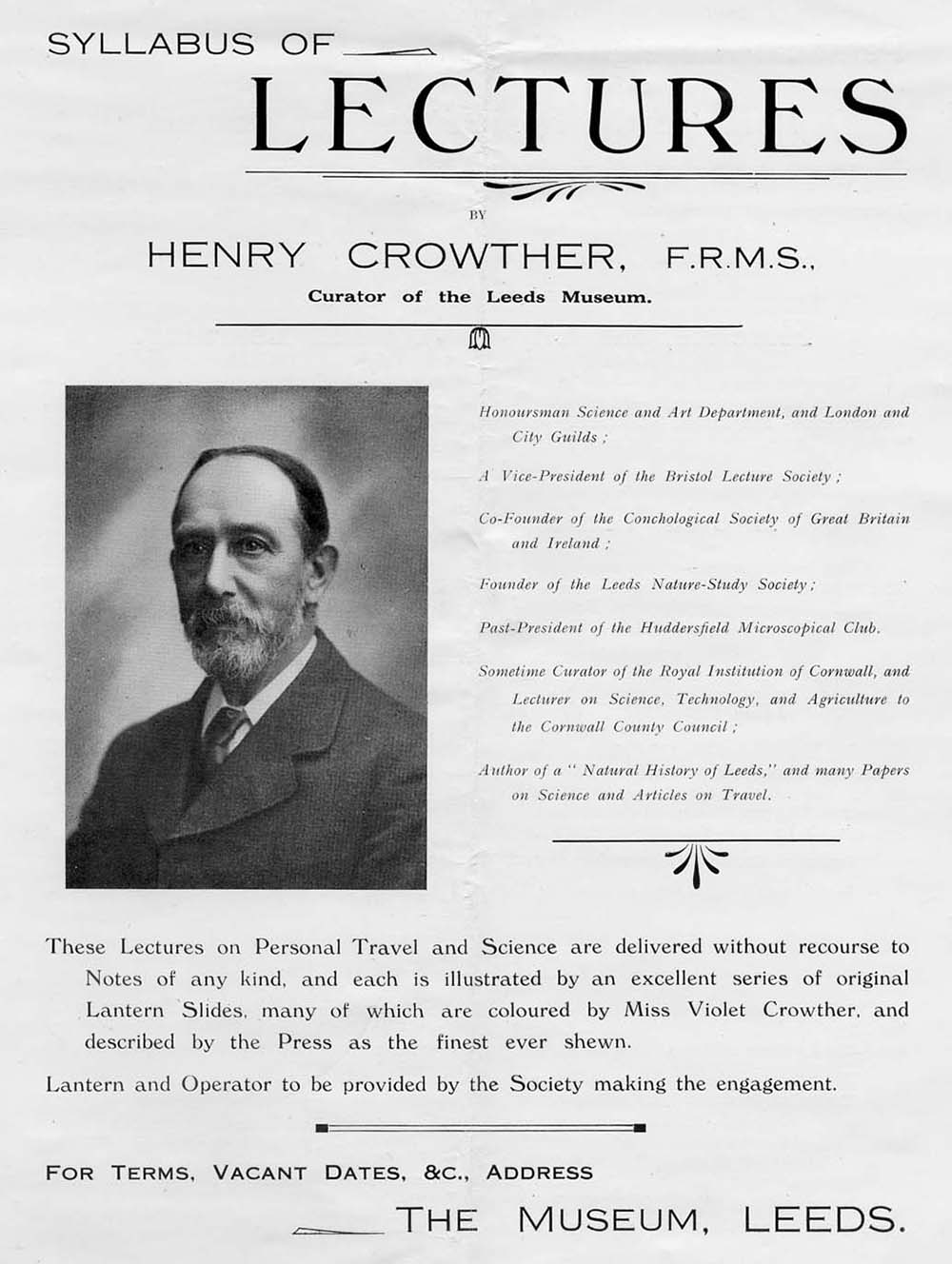

Figure 4.

An undated flier for Henry Crowther’s public lectures. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://cypriotartleeds.wordpress.com/2012/10/31/henry-crowthers-lantern-slides/

Resources

Bracegirdle, Brian (1998) Microscopical Mounts and Mounters, Quekett Microscopical Club, London, pages 26 and 126, and Plate 11-S

Clark, Edwin Kitson (1924) The History of 100 Years of Life of the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society

The Conchologist (1893) Editor’s notes, page 156

Crowther, Henry (1905) The museum as a teacher of nature-study, Museums Journal, Vol. 5, pages 5-14

Crowther, Henry (1925) Some conchological byways, Journal of Conchology, pages 39-43

England census and other records, accessed through ancestry.com

Garforth, W.E. (1912) British coal-dust experiments, Transactions of the Institute of Mining Engineers, pages 220-245

Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip (1877) Exchange offer from Henry Crowther, page 96

Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip (1879) Exchange offer from Henry Crowther, page 120

Harris, W.H, and Henry Crowther (1883) Suggestions for an exchange club, Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip, pages 209-210

Jackson, J. Wilfrid (1927) History of the Conchological Society, Journal of Conchology, pages 65-70

Journal of Conchology (1938) Henry Crowther (1848-1937), pages 69-70

Journal of the Royal Institution of Cornwall (1888) page 390

Journal of the Royal Microscopical Society (1936) Fellows, “1891, Crowther , Henry , M.Sc. , F.Z.S., 52 , Brudenell Mount , Hyde Park , Leeds”

List of Fellows of the Zoological Society of London (1926) “1925, Crowther, Henry, Esq., F.R.M.S., The Museum, Park Row, Leeds”

Nature (1921) Royal Microscopical Society, page 224

The Naturalist (1876) Leeds Naturalists Club and Scientific Association, “Mr. H. Crowther presented two beetles from Agbrigg, Clivina fossor and Donacia sericea”, page 12

The Naturalist (1876) Conchological Society of Great Britain and Ireland, page 126

The Naturalist (1889) “An appointment of interest to Leeds naturalists is that of Mr. Henry Crowther, who, while Assistant-Curator at the Leeds Museum, was one of the four conchologists who founded the 'Conchological Society' in 1876, to the curatorship of the Museum at Truro, in Cornwall”, page 211

Reeve, Anna (2012) Henry Crowther’s lantern slides, https://cypriotartleeds.wordpress.com/2012/10/31/henry-crowthers-lantern-slides/, accessed August, 2024

Transactions of the Yorkshire Naturalists' Union (1893) Members, “1896, Crowther, Henry, F.R.M.S., Curator of the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society’s Museum; 52, Brudenell Mount, Headingley, Leeds”