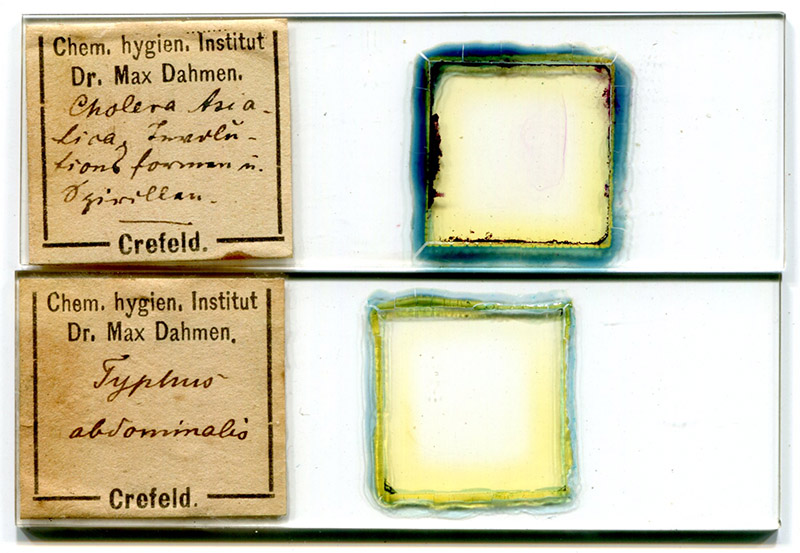

Figure 1. Microscope slides that were prepared by Max Dahmen in 1891 (see Figure 2). These are Gram stained preparations of cultured “Cholera Asiatica” (Vibrio cholerae) and “Typhus adominalis” (Salmonella enterica typhi).

Max Dahmen, ca. 1860 - 1898

by Brian Stevenson

last updated December, 2024

Max Dahmen operated a bacteriology laboratory (“Chemical and Hygiene Institute”) in Crefeld, German, from ca. 1891 until his early death in 1898. He was referred to as “Doctor” and appears to have been a physician. Dahmen developed numerous methods for culturing and examining microbes, and published extensively. He taught bacteriological techniques to area physicians and other interested people, and sold prepared microscope slides (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Microscope slides that were prepared by Max Dahmen in 1891 (see Figure 2). These are Gram stained preparations of cultured “Cholera Asiatica” (Vibrio cholerae) and “Typhus adominalis” (Salmonella enterica typhi).

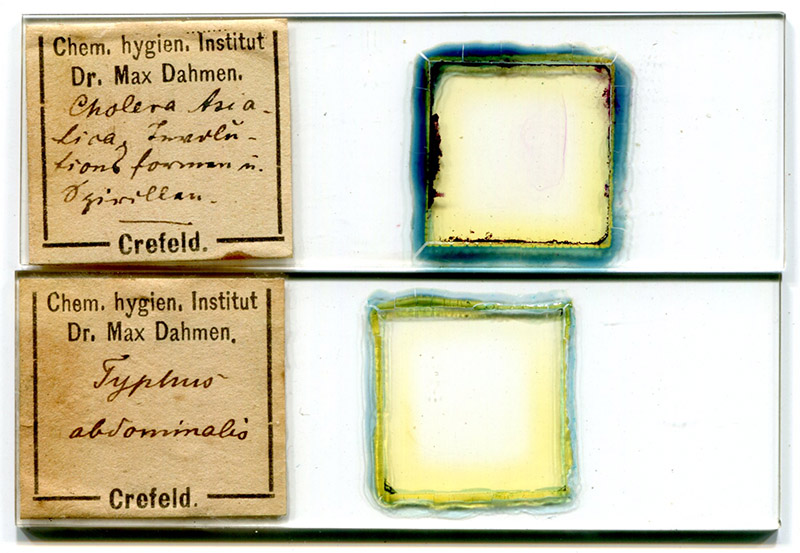

Figure 2.

A box of bacteriological slides by Max Dahmen. Handwriting inside the lid indicates that it was acquired for Christmas, 1891. The box originally contained 20 slides.

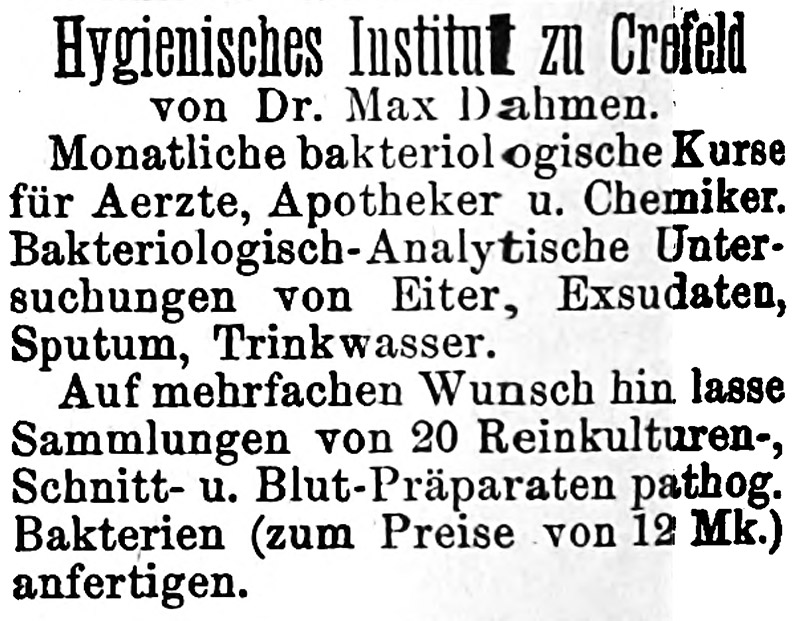

Figure 3.

An early 1892 advertisement from Max Dahmen, offering monthly courses in bacteriology to physicians, apothecaries, and chemists, and boxes of 20 prepared microscope slides of bacteria (see Figure 2). From “Medico”.

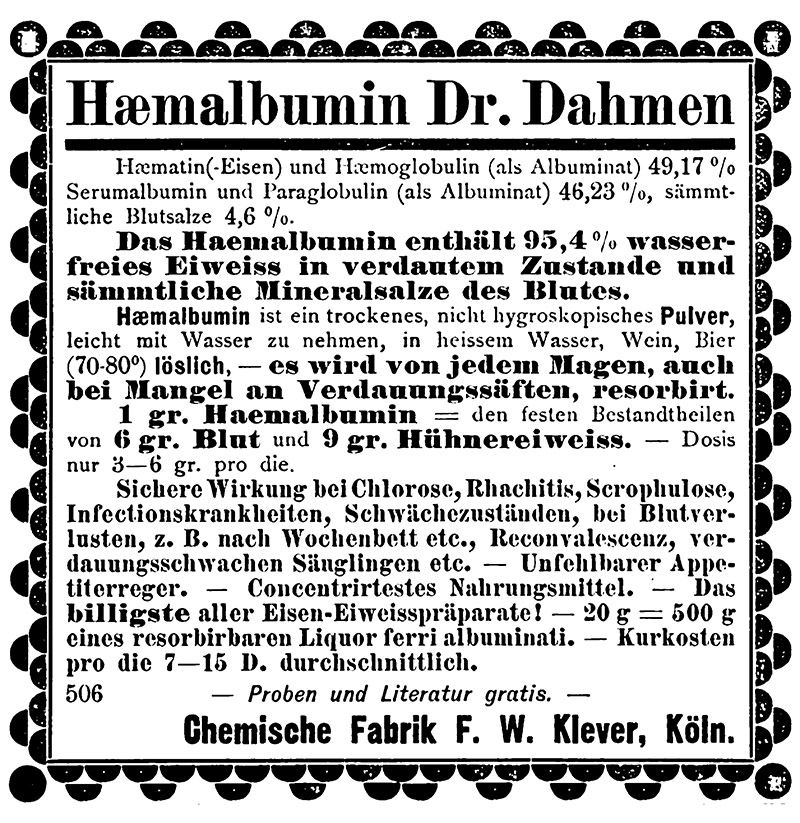

Figure 4.

Dahmen concocted a substance that he called “haemalumin” in early 1894. A mixture of salts and proteins, it was marketed as a therapeutic liquid food for treatment of chlorosis, anemia and other conditions. This 1895 advertisement indicates that it Dahmen’s preparation was manufactured and distributed throughout Germany. From “Ärztliche Rundschau”.

Very little has been discovered about Max Dahmen’s life before he established his business. People surnamed “Dahmen” were living in Crefeld throughout the 1800s, so it is likely that he was born in that town. A memoriam of his life stated that Dahmen became a doctor “in the late 1880s” and gave an age at death of 37 years old, indicating that he was 18-19 years old when he was awarded the title. Dahmen’s skills as an experimental bacteriologist suggest that he had received in-depth training, possibly while at medical school. It is probable that our microscopist was the father of a Max Dahmen who was born in Crefeld in 1892, and died in 1984.

In 1891, Dahmen published details of his improved method to prepare tuberculosis bacteria from sputum. The Lancet reported, “It has been tested in Koch's new Institute for Infectious Diseases, and Dr. Dahmen has received a letter from that establishment informing him of the success of the investigation”.

The microscope slides shown in Figures 1 and 2 were prepared by Dahmen in late 1891, and he was advertising to teach bacteriology methods at that same time (Figure 3).

Sliced potatoes were still widely used for culturing bacteria. The potatoes were heated in an autoclave or steam oven within bowls, then sliced while still hot. After cooling, samples to be tested were spread onto the potato halves. In 1892, Dahmen published a description of a bowl and lid combination that he designed, which significantly reduced the likelihood of contamination by airborne microbes.

Also during that year, he also published on culturing cholera bacteria and testing water for contaminating bacteria.

In 1893, Dahmen published his observations that, “certain of the superficial colonies of some vibrios (V. Koch, Finkler-Prior, Metschnikoff, Denecke) are distinguishable into two varieties called a and β colonies”. He also suggested, “that the difference in the characters of an epidemic are to be explained by the differences noted in the a and β colonies and their mixtures, and would further explain the absence of severe symptoms in Pettenkofer and others by supposing that they took β cultivations”.

Later that year, Dahmen wrote, “Bakteriologische Untersuchungen über die baktericide Kraft der Vasogene (oxygenierten Kohlenwasserstoffe)” (“Bacteriological studies on the bactericidal power of Vasogene (oxygenated hydrocarbons)”). Vasogen was described as “the trade name for Vasolinum oxydatuni. … The new product makes an emulsion with water without any addition, and the product seems to be a permanent one. It is also a solvent for many otherwise difficult soluble medicaments, among them iodoform, creosote, ichthyol, menthol, chrysarobin, pyrogallol, chloroform, camphor, pyoktannin, etc. By means of vasogen these remedies may be employed in dressing wounds, ulcers, etc., on the mucosa, as well as the skin”.

In 1894, Dahmen began marketing a product that he called “Hämalbumin” (Figure 4). F.P. Foster in the 1897 Reference-Book of Practical Therapeutics described this: “Dr. Max Dahmen, of Crefeld (Dtsch. med. Woch., Apr. 5, 1894), has given the German name Hämalbumin to a preparation said to contain all the salts and albuminoids of blood, to be readily soluble in warm water and in alcoholic liquids, and to be susceptible of absorption by a stomach utterly incapable of secreting any digestive principle. He thinks, therefore, that it is absolutely sure to cure chlorosis. It has been used successfully by various observers in that disease, in anaemia, in scrofula, in ulcer of the stomach, and in rickets. The dose is 15 grains, from three to five times a day. Occasionally it gives rise to troublesome constipation”.

Max Dahmen died “at the end of February”, 1898, at the age of 37. I did not find any details on the cause of death, although it would not be a surprise if he was killed by one of the pathogenic bacteria that he studied. Quite a few early bacteriologists died from infections.

The journal Leopoldina wrote, “At the end of February 1898, the chemist Dr. Max Dahmen, who made a name for himself through bacteriological work, died at the age of 37 years. Dahmen introduced several innovations in the technology of bacteriological examinations. He devised a process for isolating pathogenic microorganisms from pus, sputum, and exudates, as well as a new process for detecting tubercle bacilli in sputum. Studies carried out by Dahmen should be followed by larger investigations on detection of cholera vibrios. In connection with this is a work on the cholera pathogen and the comma-shaped bacilli that are morphologically close to it, such as the Finkler-Prior, Metschnikoff and Denecke comma-bacillus. Dahmen based his investigation on a more detailed study of the fertilization processes in the individual vibrios. In this context, Dahmen worked on the theory of the bacteriological examination of water. Also worth noting are Dahmen's studies on the bacteria-killing power of Vasogene and on the biological conditions of the tubercle bacilli. Dahmen's works have mostly appeared in the 'Zentralbl. f. Bacteriol.', in the 'Chemiker-Ztg.', in the 'Münch. med. Wochenschr.' and in the 'Pharm. Ztg.' A doctor since the end of the eighties, Dahmen has maintained a bacteriological laboratory in Krefeld, which also served teaching purposes” (translated).

Resources

Adreßbuch und Warenverzeichnis der Chemischen Industrie des Deutschen Reichs (1892) “Dr. Max Dahmen, chem.-techn. u. hygienisch. Institut in Crefeld, Dreikönigenstr. 103”, Vol. 3, page 411

Ärztliche Rundschau (1895) Advertisement from F.W. Klever for Max Dahmen’s “Hämalbumin”, Vol. 5, page 266

Berliner Klinische Wochenschrift (1891) Advertisement from Max Dehman, Vol. 28, December 28 issue

British Medical Journal (1898) Deaths in the profession abroad, “Dr. Max Dahmen, well known by a series of publications on bacteriology, and for many years director of a bacteriological laboratory at Krefeld, where he gave courses of practical instruction on the subject”, March 19 issue, page 796

Canadian Druggist (1895) New remedies and chemicals, pages 83-87

Chemiker-Zeitung (1892) Advertisements from Max Dahmen, Vol. 16, multiple issues

Dahmen, Max (1892) Die feuchten Kammern, Zentralblatt für Bakteriologie und Parasitenkunde, Vol. 12, page 466

Dahmen, Max (1892) Die Nährgelatine als Ursache des negativen Befundes bei Untersuchung der Faeces auf Cholerabacillen, Zentralblatt für Bakteriologie und Parasitenkunde, Vol. 12, pages 620-622

Dahmen, Max (1892) Die bacteriologische Wasseruntersuchung, Chemiker Zeitung, Vol. 16, pages 861-862

Dahmen, Max (1892) The bacteriological examination of water, Chemical News and Journal of Industrial Science, pages 13-14, translated from Chemiker Zeitung

Dahmen, Max (1893) Ueber gewisse Befruchtungsvorgänge bei den Vibrionen Koch, Finkler und Prior, Metschnikoff und Denecke und die epidemiologischen Konsequenzen, Zentralblatt für Bakteriologie und Parasitenkunde, Vol. 14, pages 43-53

Dahmen, Max (1893) Bakteriologische Untersuchungen über die baktericide Kraft der Vasogene (oxygenierten Kohlenwasserstoffe), Zentralblatt für Bakteriologie und Parasitenkunde, Vol. 14, pages 720-724

Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift (1894) Advertisement from F.W. Klever for Max Dahmen’s “Hämalbumin”, Vol. 20, Dec. 27 issue

English Mechanic and Mirror of Science and Art (1891) “It is stated that a new method of demonstrating the presence of tubercle bacilli in sputum has been devised by Dr. Max Dahmen, of Crefeld, and as it has been tested and found correct, he has been advised to publish it”, Vol. 54, September 11, page 30

Find-a-Grave (accessed December, 2024) Max Dahmen, 1892-1984, www.findagrave.com/memorial/233790216/max-dahmen

Foster, Frank Pierce (1897) Reference-Book of Practical Therapeutics, D. Appleton & Co., New York, Vol. 1, page 463

German vital records, accessed through ancestry.com

Journal of the Royal Microscopical Society (1893) Fertilization-processes in Vibrios, summary of Dahmen (1893) Zentralblat fur Bakteriologie und Parasitenkunde, Vol. 14, pages 43-53

The Lancet (1892) A new method of demonstrating the presence of tubercle bacilli in sputum, page 594

Leopoldina (1898) Memoriam of Max Dahmen, page 52

Medico (1892) Advertisement from Max Dahmen, page 284

Occidental Medical Times (1892) A new method for determining tubercle bacilli, Vol. 6, page 74