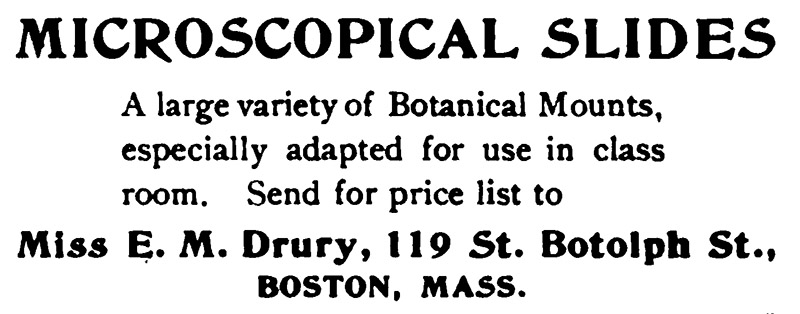

Figure 1. Examples of microscope slides that were prepared by Ella M. Drury, circa 1890s. She specialized in botanical subjects.

Ella M. Drury, 1856 - 1948

by Brian Stevenson

last updated March, 2016

Ella Drury was a rarity among women of her time: an unmarried scientist. She was a daughter of a relatively wealthy farmer, who left her a substantial inheritance that probably aided her independence. After Ella graduated from college, she operated a private teaching laboratory for women, and taught summer sessions at Woods Hole and other institutions. She also produced quality microscope slides, specializing in botanical subjects. Her college alumni magazine boasted (incorrectly) that “Miss Ella M. Drury, 1879, has the distinction of being the only person in this country whose livelihood is obtained by making delicate botanical specimen slides for microscopes”.

Figure 1.

Examples of microscope slides that were prepared by Ella M. Drury, circa 1890s. She specialized in botanical subjects.

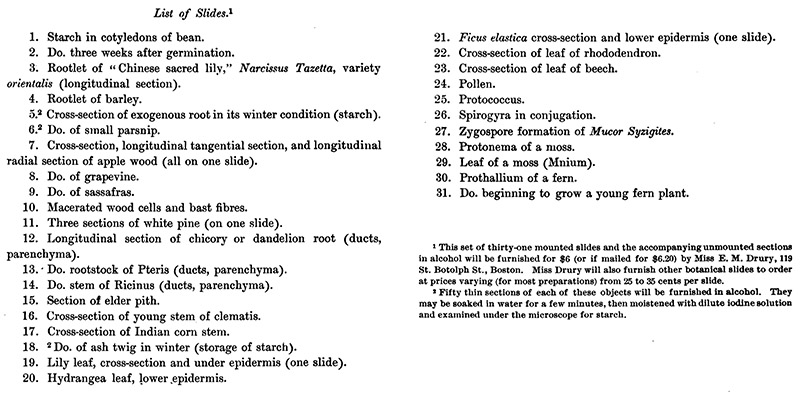

Figure 2.

An advertisement from ‘The Observer’, 1896.

Curiously, the most insightful piece of personal information on E.M. Drury comes from a letter that was attached inside an auctioned clock that Drury once owned (the clock is shown below, as Figure 6):

“The last previous owner of this clock was Miss Ella M. Drury, born August 16, 1856, a member of the first class that graduated at Wellesley College, and at present (1933) an inmate of the old folks home in Natick, Mass. She was the only child of Willard Drury by his second wife, Roxa Broad, born February 13,1823 and died October 5, 1875. The original owner of the clock was Abel Drury, who married December 1, 1803, Nabby Broad of Natick by whom he had Otis Drury, born November 16, 1804, and died October 2, 1883, and Willard Drury (above mentioned), born April 18, 1806”.

The Drurys were an old, established family in Natick, Massachusetts, USA. Ella’s father, Willard, married twice, evidently having one child with each wife. He married Louisa Haynes on May 6, 1829. Their daughter, Abigail, was born in 1831. Louisa died in 1849, and Willard remarried on June 1, 1853, to Roxa Broad. Ella was born in August, 1856. Roxa died in 1875. The 1870 census listed Willard’s estate at $4000 in real estate and $10000 in personal property. His widowed mother, who lived with the family, had an additional personal estate of $2600.

Ella attended Wellesley College, a prestigious women’s school, from 1875-79. She graduated with an A.B. (Bachelor of Arts).

After college, Ella returned to her father. The 1880 census lists her as “keeping house” with 74 year-old Willard. They were assisted by a live-in servant. Willard died on July 13, 1882. His will left half ownership of his house and personal property to each daughter, and also settled each with substantial amounts of land.

Ella taught a full course in microscopy during 1889, suggesting that she probably began private teaching before that time. The 1889 American Monthly Microscopical Journal wrote, “Miss Ella M. Drury, of Natick, Mass., has been in charge of the department of microscopy at the Martha's Vineyard Summer Institute. She teaches the use of turn-table and cell-making; balsam, dry and fluid mounts; caustic potash preparations, staining and double staining of ferns, sections, and animal tissues; section cutting of both vegetable and animal materials. Dishes, bottles, microscope, microtome, all media, reagents, and materials are furnished. The laboratory is open from 8 A.M. to 6 P.M. The five-weeks' term closes August 10th”. An 1894 paper from Drury, on “How to Interest People in the Microscope”, is reproduced at the end of this essay, providing insight on her teaching methods. Those lessons are still practical.

During the summer of 1890, Drury took a course at the Woods Hole Marine Biological Laboratory. The following year, she was listed as a Member of the Laboratory, and subsequently taught courses there.

The 1890 Wellesley Prelude, a college alumni magazine, wrote, “Miss Ella Drury, '79, is conducting private classes in Microscopy, in Boston”. The next year, The Report of the Association for the Advancement of Women wrote, “The laboratory of Miss E. M. Drury in Boston, Mass., affords a needed opportunity for women pursuing scientific work in Zoology, Botany and Petrology. She gives courses of study in specific or much advanced work. One very attractive course this year includes rock, coral and shell lectures”.

Drury kept up on her own studies. The 1893 Harvard University Catalogue included, “The summer course in Botany for 1893 was held at the Botanic Garden from June 30-Aug. 3. It was under the instruction of Professor D.P. Penhallow, of McGill College, Montreal, assisted by Mr. Barber. The course consisted of two parts: first, laboratory work on Vegetable Morphology (analysis and classification), supplemented by a course of daily lectures on the principles of Vegetable Morphology and Physiology; and secondly, laboratory work on the Microscopical Anatomy of the higher plants, supplemented by demonstrations and lectures. The following persons were in attendance: … Drury, Ella M., A.B. (Wellesley Coll.), Private Teacher, Boston”.

Substantial retail of microscope slides appears to have begun in 1894. An editor of The Observer, probably microscopist Mary Ann Booth, wrote, “So far as the writer knows, no attempt has been made to fill the long apparent need of carefully prepared microscopical mounts illustrative of the various features of vegetable histology, and arranged in definite and connected series. The expert microscopist might cull what he needed from the dealers’ lists. But average teachers, particularly in those schools into which microscopes have recently been introduced, have been sorely perplexed. The issue of series of slides by such a well known microscopist as Miss E. M. Drury, of 119 St. Botolph St., Boston, is especially timely, and from a familiarity with Miss Drury's work, and a personal acquaintance with Miss Drury herself, the writer can commend these preparations in the highest terms. Series I answers the question so often asked, ‘What classes of objects are the best calculated to awaken the interest of children in things microscopical by a dozen slides best seen with a magnification of 50 diameters. Series II is more advanced and requires a power of too diameters. Series III is a histological study of tissues found in stems and woods, requiring an amplification of 300 diameters, which study Series IV continues. Series V illustrates the contents of cells from a physiological point of view. A set of 24 slides illustrating the development of stomata is also listed. Also one suitable for an evening's entertainment. Besides these preparations, Miss Drury offers other lists of the algae, fungi, etc., which will be sent t0 applicants, We understand that Miss Drury is to continue her laboratory instructions, the courses offered being extremely useful to teachers and others desiring to perfect themselves either in the ordinary or more advanced lines of practical microscopical work”.

Further insight on the scope of Drury’s microscopical preparations was provided by a list of 30 objects she prepared to accompany Joseph Bergen’s 1896 Elements of Biology, shown below as Figure 3. Ella also produced photomicrographs of those subjects, “for unmounted blueprints, $0.85 per dozen; for mounted silver-prints, $2.00 per dozen”.

The 1897 Proceedings of the National Science Club reported Drury as still living at 119 St. Botolph Street, Boston. The 1900 U.S. Census shows a move, to 45 Munroe Street, Boston, where she lived with a cousin, Charlotte Powers.

Bergen and Davis’ 1907 Laboratory and Field Manual of Botany listed as a dealer, “Miss E.M. Drury, 45 Munroe Street, Roxbury (Boston), Mass. Slides and preserved material”. The 1914 Guide to Nature listed “Miss E.M. Drury, 45 Munroe Street, Roxbury, Massachusetts, supplies botanical slides and school series”.

Ella may have reduced her microscopy output after that time, as there are no more records of her selling slides or other materials. The 1920 census listed 63 year-old Ella living with her 89 year-old sister Abigail in Natick. The 1930 census has Ella as head of that household, accompanied only by a housekeeper.

The 1934 Wellesley College Bulletin reported a donation “From Ella M. Drury of Natick, '79, a large and valuable collection of botanical materials. The collection includes about 3,000 herbarium specimens, 40 books, nearly 11,000 carefully prepared microscopic slides, 800 unused slides of the finest glass and a miscellaneous assemblage of glassware and apparatus”. As noted above, a 1933 letter in an auctioned clock stated that Ella was then a resident in an “old folks home in Natick”, and so was likely auctioning and giving away her superfluous property.

Ella Drury died in 1948. She would have been 91-92 years old.

Figure 3.

List of 31 microscope slides prepared by Ella Drury to accompany J.Y. Bergen’s ‘Elements of Botany’ (edited for formatting considerations).

“How to Interest People in the Microscope”, by E.M. Drury, published in The Observer, 1894:

“It may be that some of the readers of The Observer have become discouraged in attempts to interest their friends in what is wonderfully beautiful to themselves, and I presume not a few have felt a wave of disgust pass through their souls as the friend, earnestly trying to seem appreciative, and feeling a necessity to liken the vision to some known object, has remarked its close similarity to a meeting-house, a bit of lace, a strainer, a pine tree, or a dog's tail. It is a fact to be borne in mind, amid these and kindred trials, that the eye must be trained before it sees correctly, and this is particularly true in the present case. The skillful microscopist is in danger of forgetting his own difficulties with his eyelashes the first time he looked through the tube upon the brilliant background and saw something glistening in the light. We do not ordinarily hold what we are looking at against the light, and this is one reason why a new observer is so dazed when he looks into the microscope. With all due regard to the good judgment and common sense of the one who fails to interest his friends in the microscope, let me say the failure is generally due to either a wrong choice of objects, or of the time selected to display them. Of course a novice with five minutes to catch a train, will not give much intelligent notice to a slide showing division of nucleus in the hair of Tradescantia, but he might take one glance at a flower seed, and remember while on the train how prettily Nature has wrapped up the embryo poppy.

Then there is another thought concerning the introduction or preface to the display. We all know that one who has heard anything highly praised in advance, rarely deems it worthy of so great praise when he sees it. It makes little difference whether it be a landscape, a work of art, or a microscopical slide. The one exploring should have the right of making his own discoveries of beauty, and rejoicing in them in his own way, however unconventional. If he likens the object to some incongruous thing - his case is not hopeless. Every one of us may be placed in a position where we cannot speak the proper language used by those at home in it. Therefore explain all that is needed, and then wait, and cordially welcome the expression of wonder or pleasure, and your reward shall be that you have won the interest of your friend.

There must be judgment exercised in the selection of objects. This will involve considerations of the age, information, and tastes of the one you wish to please, as well as the length of time advisable to be taken. Often a single object well shown is better than more - because it leaves a perfectly clear picture in the mind that is instructive to recall. Keep closely to the simple things that are easily understood and have no complicated structure.

There should be nothing to shock or disturb the observer, so you must be considerate of his natural prejudices, and however much you may enjoy the dissection of worms or the comparison of cheese mites with sugar mites, or abnormal tissue with normal - be sure the average spectator will shrink from the sight and feel uneasy over the next meal. (I would like to say all I think of the evil done by blundering people in this line.)

Confine yourself to low powers until your friend has mastered the matters of focus and moving the object on the stage - and then use high powers sparingly. Remember that the greater magnification is obtained at the sacrifice of a larger field, and that it is always best to show as much general relation between the parts of the object as is possible.

Children are fond of looking at small insects, wings, feathers, seeds, moss, sand, etc., and it is quite safe to expect that the older people will enjoy them as well. With adults, however, this difference will be noticed, more attention can be given to the details, and particularly to the adaptation of parts to the use for which they are made. Also the maturer mind will take pleasure in observing the similarities or differences between two or more closely allied objects.

Generally speaking, a lady will be interested in botanical subjects - pollen, sections of leaves or stems, with their various forms of cells and their contents, but it is the man who will give the sections of wood the closest attention. If your friend is aged, be considerate of the eyes that have passed their prime, but never allow him to feel that he cannot enjoy the pleasure the others are receiving.

Put on the stage an object that has both thickness and color, as crystals of bichromate of potassium, or sand, or a flea - something that will not be difficult to get a focus that will show satisfactorily even if it be not the best. Encourage him to remove his glasses and take time to adjust the focus to suit his eye, and the sincere delight which he will show when he finds that he can see as well as the others, will make you patient when the next one declares that it is no use in his trying to see.

Do not forget the children of the poor - or the very ignorant. A simple thing which I never knew to fail to draw attention is a fine handkerchief placed over the stage - and having caught their interest it is easy to go on, and one can never know but it may be an incentive to some waif to struggle up into greater knowledge and light.

I believe we may interest people in the microscope - not our own facts, it may be - but in something that shall give them instruction and pleasure, if we will but give it sufficient thought”.

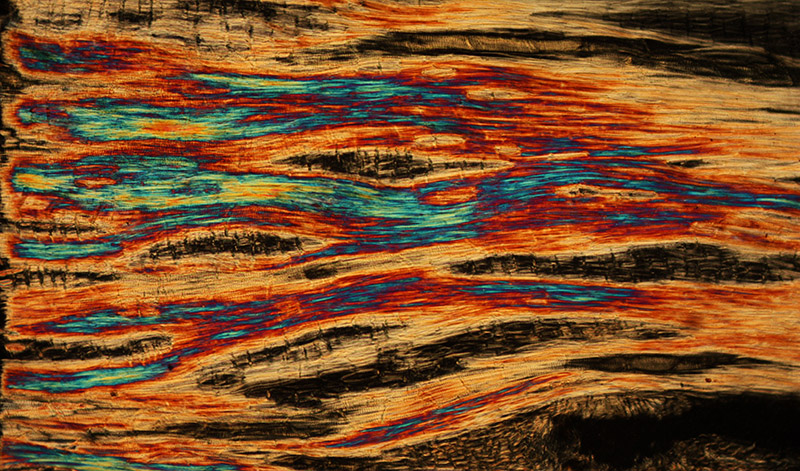

Figure 4.

Chicory root section (see Figure 1), by E.M. Drury. Viewed though 10x objective lens, between crossed polarizing filters (without selenite).

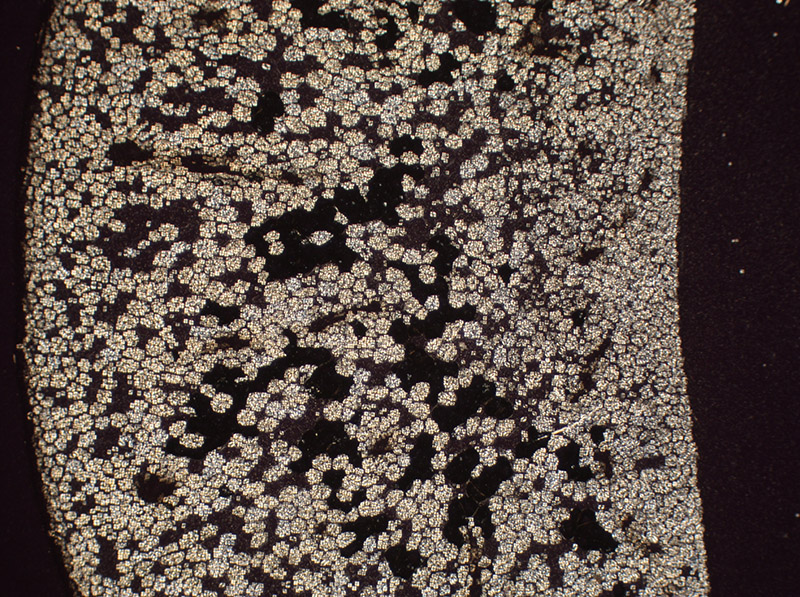

Figure 5.

Cross section of cotyledon of bean, showing starch in situ (see Figure 1). Viewed though 3.5x objective lens, between crossed polarizing filters.

Figure 6.

A clock that was once owned by Ella Drury. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Resources

The American Monthly Microscopical Journal (1889) Vol. 10, page 188

American Primary Teacher (1890) Martha’s Vineyard Summer Institute, Vol. 13, page 323

Bergen, Joseph Y. (1896) Elements of Biology, Ginn & Co., Boston, pages 250-251 and 256-257

Bergen, Joseph Y., and Bradley M. Davis (1907) Laboratory and Field Manual of Botany, Ginn & Co., Boston, page 225

Clark’s Boston Blue Book (1895) 119 St. Botolph Street, page 197

Drury, Ella M. (1894) How to interest people in the microscope, The Observer, Vol. 5, pages 337-338

Grave marker of Willard Drury, Louisa Haynes Drury, and Roxa Broad Drury (accessed March 2016) Find a Grave, http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=131082963&ref=acom

The Guide to Nature (1914) Vol. 7, page 379

Harvard University Catalogue (1893) page 460

liveauctioneers.com (2015) “Federal Inlaid Mahogany Tall Case Clock by Simon Willard”, https://www.liveauctioneers.com/item/36562764_a-rare-small-scale-massachusetts

Marine Biological Laboratory (Woods Hole, Mass.), Annual Report (1890) Vol. 3

Marine Biological Laboratory (Woods Hole, Mass.), Annual Report (1891) Vol. 4

The Observer (1894) Vol. 5, pages 347-348 and 349

The Observer (1896) Advertisements from E.M. Drury, Vol. 7, advertisement sections of multiple issues

Proceedings of the National Science Club (1897) list of members

Report of the Association for the Advancement of Women 19th Women’s Congress (1891) page 36

U.S.A. census, birth, marriage, and death records, accessed through ancestry.com

Wellesley College Bulletin (1934) page 51

The Wellesley College Magazine (1908) Vol. 17, page 281

The Wellesley Prelude (1890) page 99

Will of Willard Drury (1882) accessed through ancestry.com