John Ford, ca. 1828 - 1899

by Brian Stevenson

last updated November, 2015

This amateur microscopist was actively mounting and distributing slides from the early 1870s through the 1890s. He worked in various printing and publishing businesses, and lived at several locations in England. Preparations labeled with his Stamford and Wolverhampton addresses are somewhat common (Figure 1). Ford also advertised to exchange slides from his final home in Kew, Surrey, but I am not aware of slides labeled with that address.

Figure 1.

Microscope slides prepared by John Ford. The three on the left are dated from the early 1870s, and two bear Ford’s Stamford address. Unsigned slides, such as the papered example in the center, are occasionally found. The rightmost two slides bear Ford’s Wolverhampton address, dating them from between ca. 1874 and 1884. Another Ford slide from Wolverhampton is illustrated in Bracegirdle’s “Microscopical Mounts and Mounters”, plate 18-F. Ford also offered to exchange microscope slides from Kew, Surrey, in the early 1890s.

John Ford was born in Derbyshire, probably during 1828, according to later census. His name was fairly common, and neither his birthplace nor parents have been conclusively identified.

He was certainly the man who married Eliza Sarah Briggs on February 4, 1849, in Nottingham. Their first child, William, was born in 1850, in Preston, Lancashire. The 1851 census recorded the 24 year-old John Ford as being a “newspaper reporter” The Fords appear to have been doing fairly well at that time, as they employed a domestic servant. The family moved to Stamford, Lincolnshire in the mid-1850s, son John being born in Preston around 1855, and daughter Eliza born in Stamford during 1858.

The 1861 census recorded John working in Stamford as a “book seller & stationer, employing 2 men & 3 boys”, and the 1871 census reported “book seller & printer, employing 1 man, 4 boys & 1 female assistant”. The family retained two domestic servants at the times of each census.

The earliest known record of Ford’s involvement in microscopy is an exchange advertisement from the February, 1872, issue of Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip (Figure 2). Ford made three other requests in that popular science magazine during 1872, as well as a brief letter on “dead flies”. He issued one more exchange offer from Stamford, in the May, 1873 issue.

Ford evidently moved from Stamford to Wolverhampton, Staffordshire, around 1874, based on advertisements he published for The Evening Press (Figure 3). The 1881 census recorded Ford as being a “newspaper proprietor - he and George M. Martin published several newspapers in the Staffordshire area.

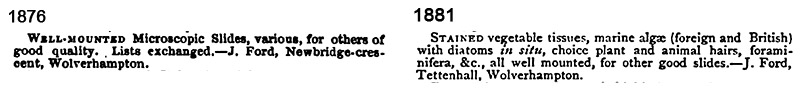

Ford issued his first identified exchange offer from Wolverhampton in 1876 (Figure 4). Also in 1876, Ford wrote a letter to Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip on “The teeth of flies”, discussing aspects of the housefly’s proboscis. He issued several other exchange offers over the next few years.

John Ford published a short paper on “Finishing slides” in an 1880 issue of Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip, providing some insight on his slide-making procedures: “Many suggestions have been made public from time to time with regard to methods of finishing microscopic slides. For example, a writer in a recent number of the ‘American Monthly Microscopical Journal’ advocates a very elaborate process, which includes the application of thick copal furniture varnish by means of a knife point and the turn-table. The slide, we are told, must then be laid aside in a dry place for ‘at least a week’, to harden, and then the superfluous varnish may be cleaned off the glass slip with cotton, stone, and water - a very roundabout and troublesome process, to say the least of it. To save inexperienced hands from needless trials of patience, waste of time, and unsatisfactory results, I am induced (with the Editor's permission) to state briefly what I have found in practice to be a very simple, easy, rapid, and thoroughly satisfactory method of finishing off balsam or dammar-mounted slides. The process is not by any means new, and I make no claim to originality in regard to it; but I have found it to work so admirably in a collection of several thousand specimens, that I feel sure young hands will be thankful for the information. Take some old Canada balsam and dilute with benzole until it is thin enough to flow freely from a sable or camel-hair pencil (the former, of what is known as the ‘duck’ size, is undoubtedly the better tool). Apply this with the turn-table in the usual way, so as to make a neat ring around and slightly projecting over the edge of the thin glass cover. Amongst the advantages of this process may be enumerated the following: 1. There is no risk of spoiling slides by ‘running in’, as too often happens with asphalte and some other coloured varnishes. 2. If the mounting of the preparation has been done with care, and there is not more than a slight exudation of balsam or dammar beyond the edge of the cover-glass, there need be no preliminary cleaning-off before ‘ringing’ the slide - an important consideration in regard to the saving of time and trouble. 3. The ring of balsam dries quickly and sets hard. 4. No after-cleaning process, like that above alluded to, is required; the slide being ready for the cabinet within a few minutes. 5. The process will be found easy of accomplishment by the veriest tyro, and the result is neat and satisfactory. - J. Ford, Wolverhampton”.

Ford joined the Postal Microscopical Society from Wolverhampton, in April, 1881.

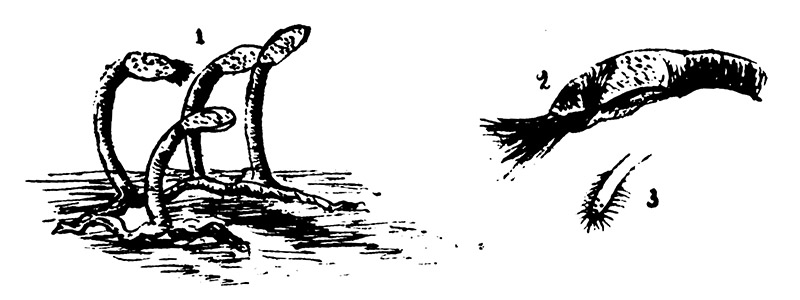

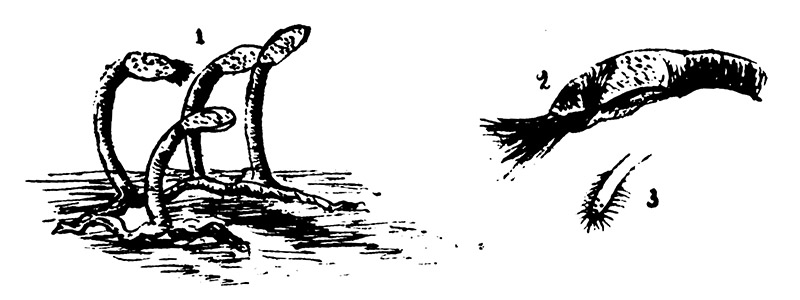

During 1882, he published two brief articles in Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip, “How do eels breed?” and “What is jet?”. He also published a paper on Anguinaria spatulata (“Snake’s Head Coraline”, now Aetea anguina) in The Journal of the Postal Microscopical Society, accompanied by his own illustrations (Figure 5).

Ford’s printing partnership with Martin was dissolved on November 28, 1884. According to the 1891 census, he took a position as a “private secretary”, in Kew, Surrey. He offered his last known exchange request from there, in 1890 (Figure 6). He died in Kew on May 30, 1899.

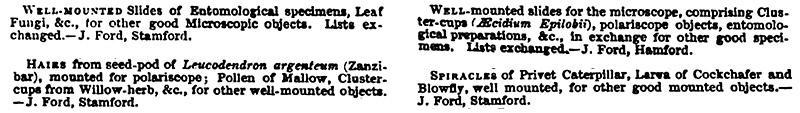

Figure 2.

1872 exchange offers from John Ford, which appeared in “Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip”. Figure 1, above, includes a Ford mount of a blowfly spiracle, which may have been exchanged in response to the advertisement on the lower right.

Figure 3.

Advertisements for the newspapers of John Ford and his partner, George M. Martin. Left, from “May’s British and Irish Press Guide”, 1876. Right, from J. Randall’s 1882 “The Severn Valley, Sketches, Descriptive and Pictorial”.

Figure 4.

Exchange offers by Ford from Wolverhampton, which appeared in “Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip”.

Figure 5.

John Ford’s drawings of snake’s head coralline, which accompanied his 1882 article in ‘The Journal of the Postal Microscopical Society’.

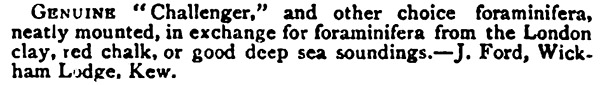

Figure 6.

Exchange advertisement from 1890, offering foraminifera from the H.M.S. Challenger’s sounding expedition.

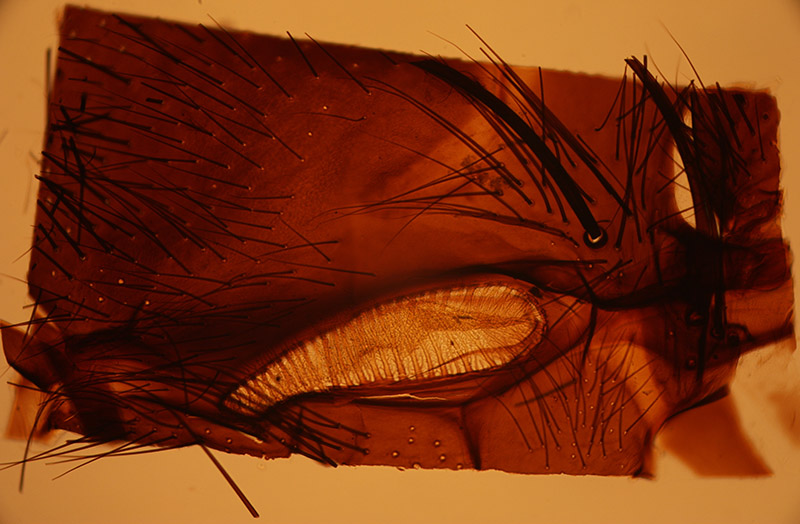

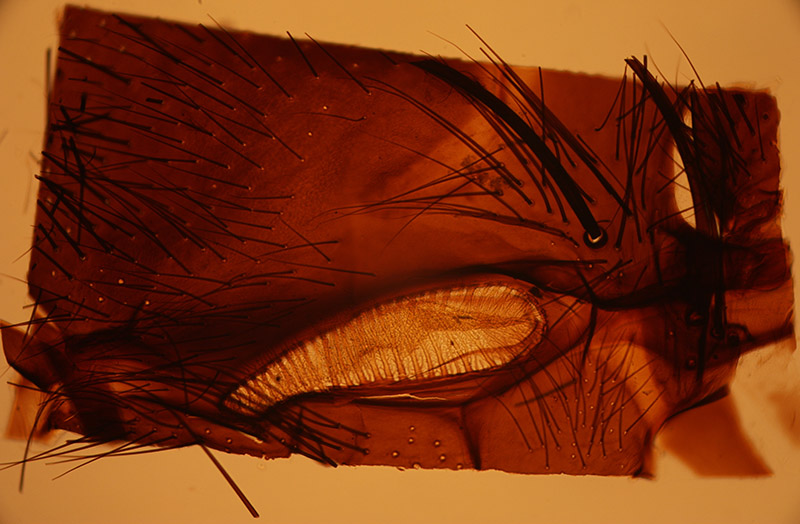

Figure 7.

“Fossil tooth from shale”, by John Ford, dated 1872.

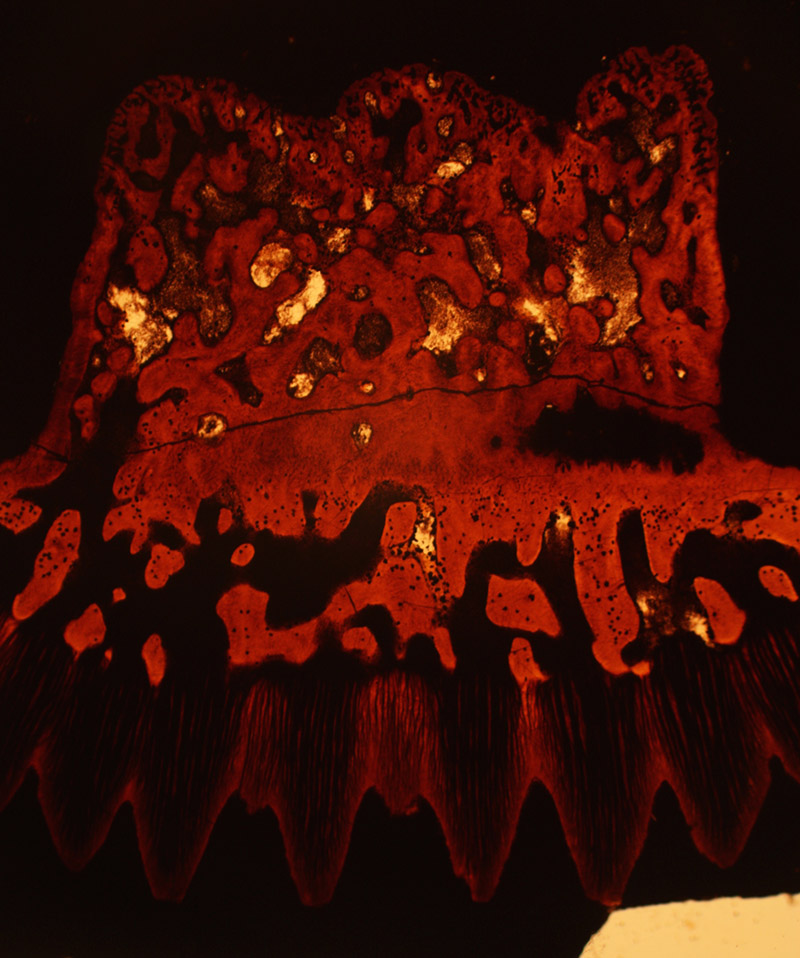

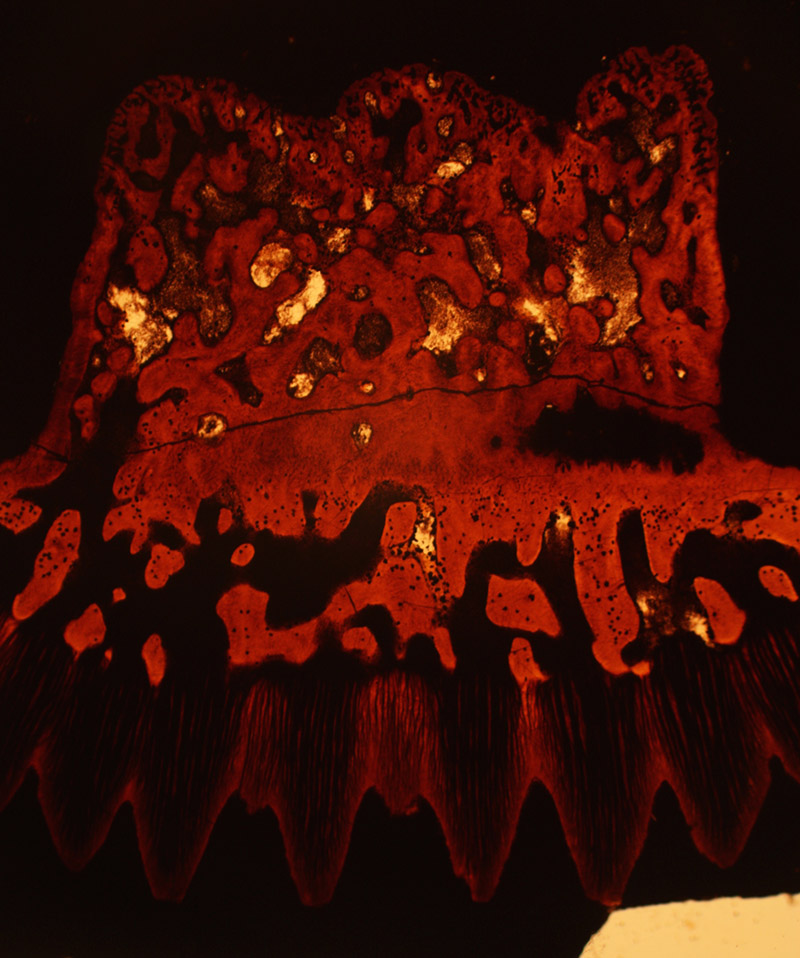

Figure 8.

“Spiracle of blow-fly”, by John Ford, dated 1871

Figure 9.

John Ford, photographed during the early 1870s. In 1874, The Postal Microscopical Society requested that all members provide a photograph of themselves, which were then used to produce a collage to be distributed as a way of “introducing” members to each other.

Resources

The Bookseller (1885) Dissolutions of partnerships: “Martin and Ford, Wolverhampton, Printers, Nov. 28”, January 7 issue, page 2

Bracegirdle, Brian (1998) Microscopical Mounts and Mounters, Quekett Microscopical Club, London, pages 43 and 140, and plate 18-F

England census, birth, marriage, and death records, accessed through ancestry.co.uk and familysearch.org

Ford, John (1872) Dead flies, Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip, Vol. 8, page 236

Ford, John (1872) The teeth of flies, Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip, Vol. 12, page 92

Ford, John (1880) Finishing slides, Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip, Vol. 16, page 230

Ford, John (1882) How do eels breed?, Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip, Vol. 18, pages 64-65

Ford, John (1882) What is jet?, Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip, Vol. 18, pages 211-212

Ford, John (1882) Anguinaria Spatulata, Journal of the Postal Microscopical Society, Vol. 1, page 47

Ford, John (1882) Dr. Hunt’s American cement for ringing slides, Journal of the Postal Microscopical Society, Vol. 1, page 193

Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip (1872) Exchange offers from John Ford, Vol. 8, pages 48, 192, 216, and 240

Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip (1873) Exchange offer from John Ford, Vol. 9, page 120

Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip (1876) Exchange offer from John Ford, Vol. 12, page 24

Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip (1879) Exchange offer from John Ford, Vol. 15, page 24

Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip (1880) Exchange offer from John Ford, Vol. 16, page 240

Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip (1881) Exchange offer from John Ford, Vol. 17, page 240

Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip (1890) Exchange offers from John Ford, Vol. 26, pages 71 and 141

Journal of the Postal Microscopical Society (1882) List of members; “April 1881 – Ford John, The Uplands, Tettenhall, Wolverhampton”, Vol. 1, page 11

Law Times, and Journal of Property (1875) “Lichfield County Court. Wednesday, Dec. 15. (Before C. Smith, Esq., Deputy Judge.) Martin v. The London And North-western Railway Company. The carriage of news parcels. Messrs. Martin and Ford, the proprietors of the Wolverhampton Chronicle, sued the London and North-Western Railway Company for the sum of £2, for loss caused through the delay of a parcel of news copy”, Vol. 60, page 147

May’s British and Irish Press Guide (1876) Advertisement for The Evening Express, page 156

Microscopical News and Northern Microscopist (1881) Exchange offer from John Ford, Vol. 1, page 276

Probate of John Ford (1899) “Ford John of 1 Cumberland-road Kew Surrey died 30 May 1899 Probate London 24 July to Eliza Sarah Ford widow and Charles Richard Mayo solicitor Effects £4957 19s 10d”, accessed through ancestry.co.uk

Randall, John (1882) The Severn Valley, Sketches Descriptive and Pictorial, J. Randall, Madeley, Shropshire, Advertisement for The Evening Express