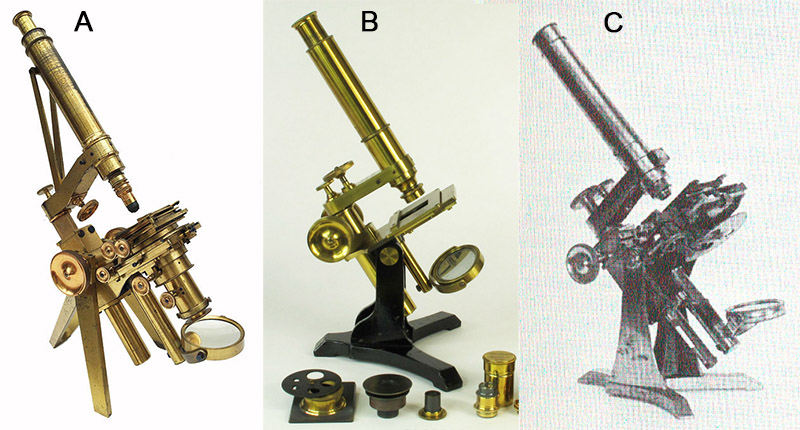

Figure 1. The only known surviving microscope that was built by J.B. Gardiner.

James Blake Gardiner (1836-1909)

successor to

John King, Jr.

by Giovanni Maga

last updated November, 2015

The work of James Blake Gardiner, optician and scientific instrument-maker of Bristol, England, is poorly known. Similar to other small entrepreneurs in provincial Victorian England, information is scarce, and instruments by Gardiner are even scarcer. There is no mention of him or of his instruments in reference collections such as those of the Royal Microscope Society (UK), or the Billings microscope collection (US). Gardiner is not mentioned in reference books about the history of microscopy, such as those written by the known historians B. Bracegirdle or G. L'E.Turner, nor he was mentioned in popular microscopy books of the 19th century, such as those written by J.T. Quekett, W. Carpenter, J. Hogg, H. van Heurck, T. Davies. Apparently, only one microscope (in the author’s collection, Figures 1 and 12) and two barometers (sold at private auctions, Figure 16) are known that bear the trademark "Gardiner, 2 Clare street Bristol".

Figure 1.

The only known surviving microscope that was built by J.B. Gardiner.

Life of James Blake Gardiner

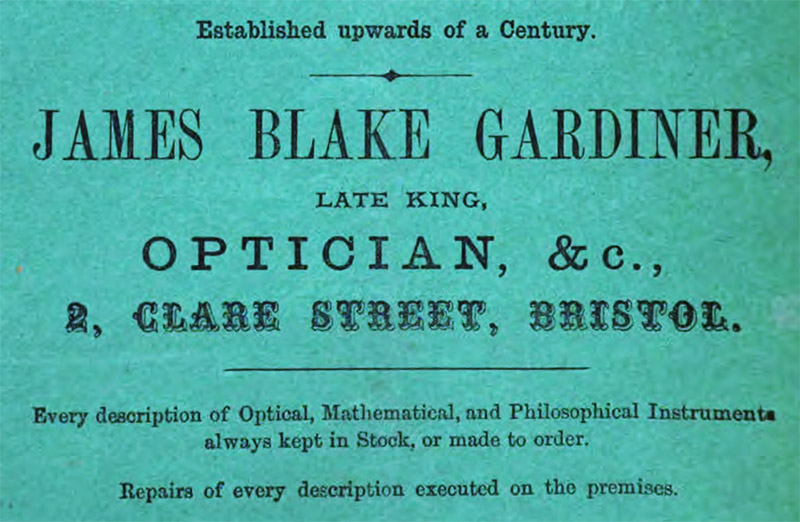

James Blake Gardiner, optician, operating at 2 Clare street in Bristol, advertised on local newspapers from 1863 to 1865 (Bristol Times and Mirror, Western Daily Press, Somerset County Gazette). An excerpt from an advertisement reads:

"Established Upwards Of Century:!! James Blake Gardiner, Late John King, Clare Street, Bristol. Optician Mathematical, Philosophical And Nautical Instrument Manufacturer. Spectacles And Eye Glasses To Suit Every Defect Of Vision". (July 7th, 1865 - Western Daily Press, Bristol).

In other advertisements, he also described himself as "son-in-law to John King". Luckily enough, this John King was a known scientific instrument maker. Additional information on King and his predecessors/successors can be found in the essay on Husbands and Clarke at this web site.

John King Jr. (London 1797 - 1871?) was the son of John King Sr., who established an optical business in Bristol at 2 Clare street in 1821. King Jr. was born in London, as indicated by census registers. John King, son of John King, was christened in 1797 at St. Marylebone, London.

John King Sr. was previously foreman to Charles and Richard Beilby, also opticians at 2 Clare street. The Beilbys were themselves successors to optician Joshua Springer, who had been active in Bristol since 1762.

While King Sr. continued the Beilby brothers business after their retirement in 1821, there are indications that he had previously been active as an instrument maker in London. The Webster signature database reports that a compound microscope, dated ca. 1775 and signed by “King I” (or “J”), was sold at Sotheby's on Dec 10th, 1973, and suggested that is was made by John King Sr.

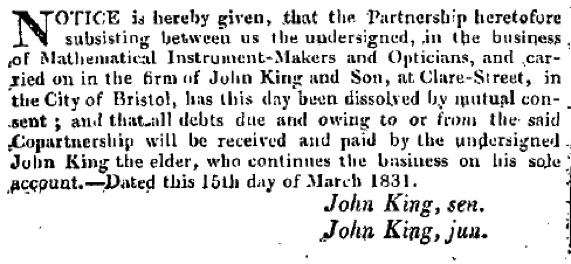

King Sr. and King Jr. operated the business together at 2 Clare street until 1831. This is certified by announcements in The Law Advertiser (1831, Vol. 9, page 279), and The London Gazette (1831, Vol. 1 page 526), that the partnership between John King Jr. and his father John King Sr. was dissolved on March 15th, 1831 (Figure 2). The business was continued by John King Sr. alone.

Figure 2.

Excerpt from the London Gazette, March 1831

Private correspondence between John King Sr. and his son, reveals tensions between the two of them, due to an affair that John Jr., who was married, had with another woman. Apparently, he abandoned his wife and children, a course of action that did not meet his father's approval. This may explain the dissolution of the partnership.

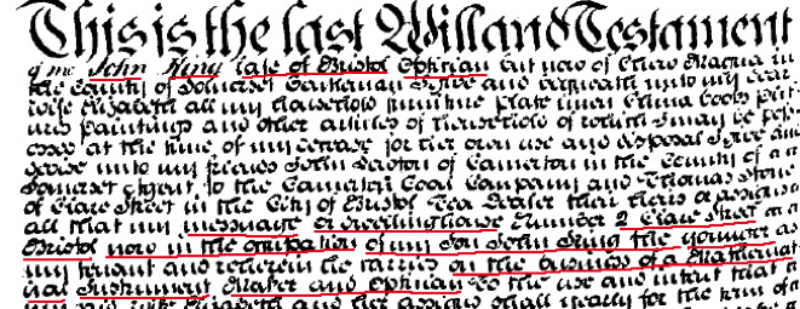

However, sentiments appear to have later improved, and John King Jr. came back to his family and settled matters with his father. We have no direct testimony of such a turn of events, but this can be inferred from King Sr.’s later actions. The will of John King Sr., dated October 1845, “late of Bristol optician”, appointed his wife, Elizabeth, and his son, John King Jr., as his sole heirs. The son John King Jr. is mentioned in the will as being an instrument maker and optician at 2 Clare street. The will also appoints John King Jr., together with wife Harriet and their children, as beneficiary of the estate in 2 Clare Street. Thus, John King Jr. took over the business after his father retired (probably in 1834, if we take into account the date mentioned by Bracegirdle).

Figure 3.

Excerpt from the will of John King Sr., 1845 (passages referring to him and his son are underlined in red).

Thomas Davies King (1819-1884), John King Jr.'s son, was also an optician. He ran the business in 2 Clare street with his father John and, for a short period, with a Henry Payne Coombs. He also opened a second shop in Denmark Street. He married Anna Reed in 1844. In 1851, he was awarded a prize at the Great Exhibition in London, for his excellent microscopes. However, in 1858 T.D. King emigrated in Canada. His journeymen Henry Husbands (ca. 1824 – 1900) and William Clarke, (ca. 1810 – 1873) took over the Denmark Street shop, and soon became renowned instrument makers.

T.D. King became a scholar in Shakespearian studies in Canada, as mentioned in his obituary in Shakespeariana (1885, Vol. 2). John King Jr. mentioned his son in his will as a "journalist" living in Canada.

Thus, from least 1858 onward, the shop at 2 Clare Street was left in the hands of John King Jr. alone. At that time, he was aged 61 and likely hoping for a younger hand to help him. It was about that time, that the lives of John King Jr. and James Blake Gardiner became intertwined.

On November 17th, 1863, James Blake Gardiner married Harriet King (born 1833, father John King) in St. Mary-Redcliffe Church, Bristol. That she was the daughter of John King Jr. is further confirmed by the English Births and Christenings database, which reports the christening in St. Mary-Redcliffe Church, of Harriet King, born on 28 Dec. 1832 of John King (father) and Harriet (mother) in Bristol. The difference between the year of birth on the christening and marriage certificates (1832 vs. 1833) can be explained by the fact that christening was on 28th December, 1832, so it is possible that the registration of the birth certificate occurred a few days later (in 1833). The St. Mary-Redcliffe Parish registers report christening of James B. Gardiner's son, Herbert Cornabie Gardiner, on August 13, 1871, and of his daughter, Ada Beatrice Anstey Gardiner, on November 30, 1873.

Thus, James Blake Gardiner became son-in-law to John King Jr. in 1863, then took up King's business at 2 Clare Street. Advertisements under Gardiner’s name started to appear in 1863.

The 1865 advertisement quoted above described James B. Gardiner’s his father-in-law as "late". However, the Census register of 1871 listed John King, born 1797 in London, as a retired optician living in Bedminster (Bristol) with his wife, Harriet. Thus, "late" here means "retired", indicating that James Blake Gardiner was running the business at 2 Clare street alone from 1865 onward.

Gardiner’s career as an optician was very shortlived.

Figure 4.

A modern view of 2 Clare Street, Bristol, where Gardiner had his business.

Figure 5.

An advertisement from the Bristol Naturalists’ Society. He placed these advertisements regularly through 1866 and up until May, 1867.

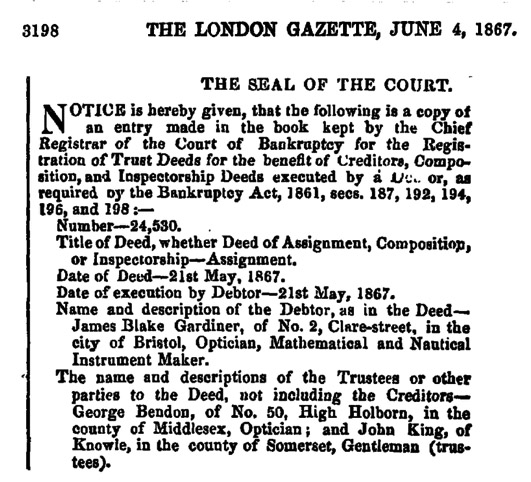

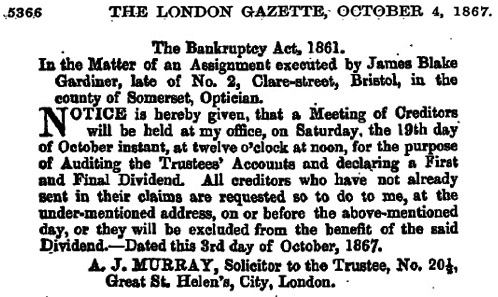

In May, 1867, a notice of bankruptcy was announced for James Blake Gardiner, optician at 2 Clare Street, Bristol (Perry's Bankrupt Gazette and The London Gazette, 1867) (Figure 6). In the Assignment Deed, a John King "gentleman", living in Somerset, is listed as a trustee for Gardiner. Somerset was also where John King Sr. lived after his retirement (as written in his will). Thus, we can assume that the King's family had an estate in Somerset, to which John King Jr. had also retired.

Figure 6.

Excerpts from the London Gazette, June, 1867, and October, 1867.

It is interesting that among the trustees nominated in the Deed of Assignment, there was a George Bendon of High Holborn, London. Bendon was one of the partners in the renowned Keyzor & Bendon scientific instruments makers' shop, which operated between 1855 and 1873 at 50 High Holborn. Presumably, Gardiner had some sort of business relationship with Bendon. The only surviving microscope signed by Gardiner (Figure 1) looks very different from the models known to have been produced by Keyzor & Bendon. This does not exclude the possibilities that Gardiner may have been a retailer for the London firm, or have acquired parts from them for his instruments. However, the fact that Bendon figured as a trustee and not as a creditor, implies that there were no pending debts between him and Gardiner.

The 1871 Bristol Street Directory does not list Gardiner (or any other optician) at 2 Clare Street, indicating that he closed the shop soon after his bankruptcy. He continued in the optical trades to some extent, although he appears to have been an employee, not an owner. The 1871 census reports him living in Bedminster (South Bristol), working as a “mercantile clerk”. The 1881 census provided more information on his occupation, describing him as a “mercantile clerk optician”, living in Weston Super Mare, Somerset. During the next decade, Gardiner moved to Hackney, London, and took up a different occupation (see below).

It is probably not a surprise that Gardiner's work as an optician lasted for such a short time. Competition from well-established opticians, such as Husbands and Clarke, who operated their shop one block away from Gardiner's, may have contributed to the poor state of Gardiner's business. Moreover, his father-in-law was already on the verge of retiring when Gardiner joined the business, and King could not tutor him for long in the arts of scientific instrument-making. This latter may have been especially significant, since Gardiner did not have any evident training in the arts of scientific instrument-making. Indeed, until at least 1861, James worked with his father in a completely different sort of business.

James Blake Gardiner, (father Joel, mother Harriet), was christened on July 12th 1836 in Bristol. James' father, Joel Gardiner (1795 - 1869), had married Harriet Elizabeth New in 1819. James' family was large. According to the 1841 census, the Gardiner household consisted of Joel Gardiner, age 45 (head), Harriet Gardiner, age 40 (wife) and Harriet (18), Joel (16), Eliza (12), James Blake (5), Anna (1). Two additional members are listed: Mary Bowen, age 40-44 and Elizabeth Jones, age 20-24 (probably housemaids). The residence is noted as Cathay Brewery, Bedminster (South Bristol). Consistent with that address, the Bristol Infirmary reported a donation of 2 guineas by Mr. Joel Gardiner, brewer in Cathay, in 1841. The 1851 and 1861 censuses similarly reported that occupation for the father. In 1861, two years before he took on the optician business on Clare Street, 24 year-old James Blake Gardiner was working as a brewer.

The Gardiner brewery suffered some significant financial hardships over the years.

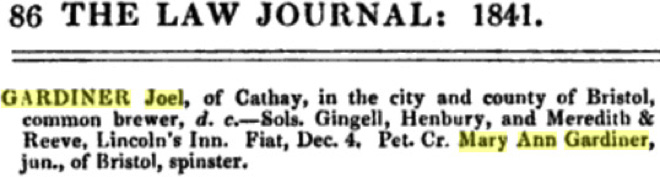

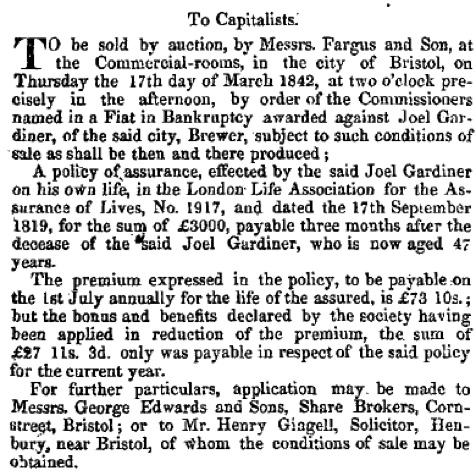

In 1841, the Law Journal Reports (vol. X, pag.86) published a notice of a Fiat for Bankruptcy of Joel Gardiner (Figure 7). Interestingly, a Mary Ann Gardiner Jr. spinster, is mentioned as the Petitioning Creditor. The England Births and Christenings reports a Mary Ann Gardiner born 1827 from Joel and Harriet Elizabeth. Thus, she was probably sister to J.B. Gardiner, even if she was not mentioned in the household register of 1841. In March 1842, even the life insurance of Joel Gardiner was auctioned as part of the bankruptcy Fiat (Figure 8).

Figure 7.

Excerpt from the Law Journal, 1841.

Figure 8.

Excerpt from the London Gazette, 1842.

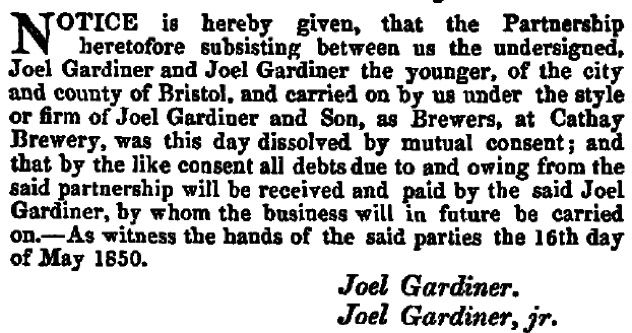

Despite the bankruptcy, the brewery was in business for several more years, apparently run until 1850 by Joel and his son, Joel Jr. This is testified by The London Gazette of May 1850, announcing the dissolution of their partnership (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Excerpt from The London Gazette, 1850.

Figure 10.

Excerpt from Matthew’s Directory of Bristol, 1864, showing James Blake Gardiner, optician, and Joel Gardiner, brewer.

The Cathay Brewery appears to have closed for good in 1864, a few years before Joel Sr.'s death. The auction of assets was advertised in The Bristol Times and Mirror on 22 October, 1864: "To Brewers, Manufacturers, And Capitalists. Desirable Properties Bristol And Valuable Life Policies. George Standee Will Sell Auction, At The Thereabout, Situated Cathay In The Parish Of Bedminster The City And County Of Bristol, In The Occupation The Proprietor, Mr. Joel Gardiner. The Property Being Well Situated Near To The Railway Termini, And Abounding With Never Failing Supply Water."

It is notable that the auction of the brewery occurred during the same year that James started his business with John King Jr. If the brewery closed because of financial hardships, it would have been logical for James to take the opportunity of stepping into the optical business of his father-in-law, even if he had no previous experience (as far as we can say).

The Bristol Times and Mirror of 20 February, 1869, advertised an auction of the land properties of Joel Gardiner (aged 74), apparently to pay his creditors. This may further suggest that James Gardiner did not inherit much of a legacy from his father. Joel Gardiner Sr. died the same year.

James’ elder brother, Joel Jr., married Charlotte Kingston Allen in 1850. They had a child, Frances, in 1851. An obituary published in The Western Daily Press on September 19 1877, reads: "Sept. 18 the residence of his brother 7, Guinea Street, Joel, eldest son of the late Joel Gardiner, of this city, aged 52."

An 1879 Bristol street directory recorded that James Blake Gardiner was living in Bristol, at 7 Guinea Street (one block away from to St. Mary Redcliffe Church). Thus, the deceased named in the obituary was Joel Gardiner Jr., and the brother mentioned was James. We can assume that James was caring at his home for his brother, likely in the event of a terminal illness of some sort.

The Gardiners moved to the London area during the 1880s. The 1891 and 1901 censuses recorded James Blake Gardiner as a “glass bottle manufacturer” in Hackney, London. He evidently owned a facility, as he was listed as being an employer. Wife Harriet passed away between 1881 and 1891, possibly during 1888. The widower lived with his children. Records from London list Gardiner as living at 13 Gore-Road Hackney, until 1907. In the last entries (1908-9) the address is registered at 26th St. John's Mansions, Hackney. A picture of the St. John's Mansions today is shown below (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Modern view of St. John’s Mansions, Hackney South, London.

The England Death Registry reports the death of James Blake Gardiner, born 1836, in Hackney, in late 1909. He was aged 73.

It is difficult, if not impossible, due to the paucity of available sources, to really know how the life of James Blake Gardiner was. From the little we know, however, he certainly lived a full life. He went through some hardships, surely, but apparently in the end he died quietly with the comfort of his family.

A microscope by James Blake Gardiner

As mentioned above, only one microscope signed "Gardiner, 2 Clare street Bristol" is known to survive and it is in the author’s collection. Indeed, it has been this instrument that sparked my interest in researching about Gardiner's life.

Figure 12.

Microscope by Gardiner (Bristol) c.a. 1863-67. In the upper left image, the foot is mounted in the "inward" orientation. The foot is mounted in the “outward” position in the upper right image. The lower images show the foot removed.

This is a third class instrument, according to the classification given by W. B. Carpenter in his reference book The Microscope and its Revelations (Churchill, London, 5th ed. 1875), meaning that it was produced for amateurs' or students' use. From a general structural point of view, this compound microscope is a bar-limb or "Ross" model (introduced for the first time by Ross in 1843). A simpler form was devised by Robert Field in 1855 and known as the "Society of Arts" bar-limb model (with the main tube detachable from the limb by unscrewing it, for easier storage). There are, however, some notable exceptions:

1) The design of the base is peculiar. The main body rests on a movable plate with two V side arms. This plate can be removed and mounted with the lateral arms in two opposite orientations: the "inward" gives a unique W-shaped or "chickenfoot" base. When mounted with the "outward" opposite orientation the base resembles the more classic Ross Y-foot. Presumably, the "inward" position, giving a lesser encumbrance, can be used for easier storage, while the opposite orientation, in reason of the higher stability given to the instrument, may be ideal when the instrument is set up for use. This may be regarded as a very unusual example of a "folding" foot.

2) The Huygenian eyepiece is not removable. In fact, the two plano-concave lenses of the ocular are not part of the barrel body of the eyepiece, as usual, but are mounted separately: the eye lens is inserted into the top-hat element that is screwed on top of the barrel, while the field lens is permanently mounted inside the barrel itself. This design was typical of old compound microscopes, but it was very uncommon in instruments produced after the 1830s. So, this instrument reflects a quite simple craftsmanship of the manufacturer and an "old" way of conceiving the optical parts of the microscope. The distance between the eye lens and the field lens is ca. 32 mm, corresponding to ca. 4X magnification power.

It would be possible, in principle, to obtain a different range of magnification by replacing the top element containing the eye lens with the one of another ocular. I experimented successfully this method with the eye lens of a top-hat 8X ocular of comparable age (c.a. 1880), almost doubling the magnification power of the objectives.

3) No fine focusing is present (it is actually unnecessary due to the low magnification power of the instrument).

4) The objective thread is not yet the RMS standard one, which was introduced in 1858 but took time to be universally used.

5) The mirror is mounted on a bar orthogonal to the plane of the stage and screwed under the stage. This is again different from the vast majority of bar-limb models, where the mirror is usually attached to the main bar carrying the rack and pinion mechanism for the coarse focusing. A similar design (i.e. a separate bar for the mirror) can be found in a microscope by T.D. King and on an early model by Husbands & Clarke (Figure 13). The Billings Microscope Collection shows one example of a similar arrangement in an early model by Ross. Thus, this uncommon design has been probably experimented in early models but has been later abandoned, probably because it limits the movements of the mirror. It is not known who was the first to introduce it. The model by Ross predates the one by T.D. King, but too few specimens are known by the latter to be able to make an attribution.

Figure 13.

Examples of other makers’ microscopes that used a similar mirror-mounting style as that used by J.B. Gardiner.

(A) Microscope by T.D. King, ca. 1855. Adapted from http://www.antiquemicroscopesandslides.com/#!thomas-davies-king-paris-exposition-1855/c15oz .

(B) Microscope by Husbands and Clarke c.a. 1870. Adapted from http://www.fleaglass.com/ads/victorian-microscope-by-husbands-and-clarke-of-bristol/.

(C) Microscope by Ross 1841. Adapted from The Billings Microscope Collection.

A barrel is screwed under the stage, holding a rotating wheel with three different apertures to regulate the amount of light. No condenser lens is present. The microscope comes with two unmarked, multiple-lens composite objectives, giving an approximate range of magnifications from ca. 40X - 60X (with the lowest power) to 80X - 120X (with the highest power), as empirically determined by visual comparison of the same objects observed with another microscope at known magnifications.

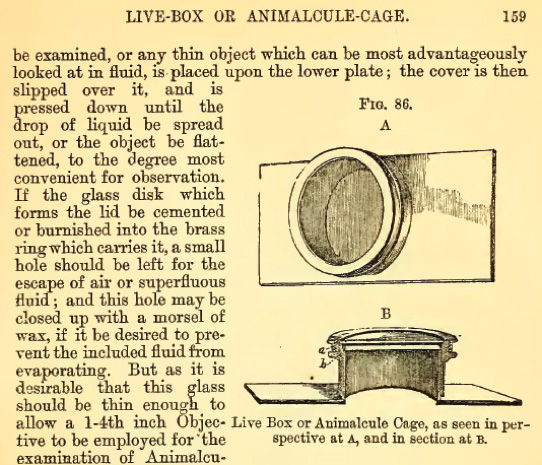

The microscope came to me also with a live box observation glass, a device very popular among the 19th century English microscopists, especially devised for observation of live small animals (such as protozoa, unicellular algae etc.). The contraption is illustrated in the Carpenter's book (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

A live box used in the 19th century (W. B. Carpenter, The microscope and its revelations. 5th ed. 1875, Churchill London).

As for the overall conditions, they are fair to good.

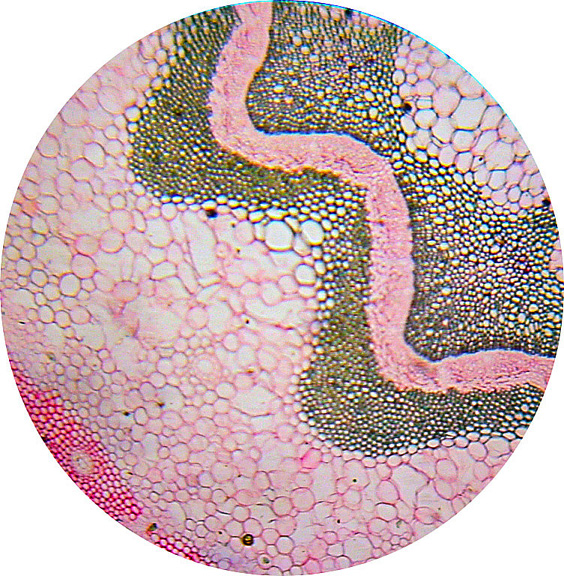

The optics are still excellent, with no sign of hazing, mold or scratches and giving sharp clear images. Figure 15 shows a down-the-tube photomicrograph of a prepared section of Acacia stem, taken from my collection of antique microscope slides.

Figure 15.

Acacia stem, double staining (Hornell Biol. Station, Jersey c.a. 1901) seen with the microscope at approx. 80X (picture taken with a Canon digital camera).

The coarse focusing is a bit slack, due to loss of tight connection between the rack and pinion, so that the focus position has to be manually held in some instances. But the mechanism is still capable of attaining precise focusing, even at the highest magnification. All the other mechanical parts are in order. The original lacquer is mostly lost, and there are some signs of wear and spots on the tube and base, according to the age of the instrument.

Based on the scarce historical information available, the microscope can none the less be accurately dated between 1863 and 1867, with the lower estimate more likely, judging from the non-standard thread of the objective lens. The absence of a serial number (a common event among small manufacturers) may suggest a small production, perhaps made on special order by a customer.

It must be noted that many retailers of optical instruments were branding their names on instruments made by others. This, however, seems not likely to be the case with Gardiner, based on three established facts:

1) His father-in-law, operating his business at 2 Clare street, was himself a renowned scientific instruments maker.

2) Gardiner advertised his business qualifying himself as a "manufacturer" not a "retailer".

3) In the bankruptcy notice (Figure 6), Gardiner is also qualified as a "maker". Among the trustees assisting Gardiner, it was also named George Bendon of the renowned Keyzor & Bendon scientific instruments makers shop, operating in London between 1855 and 1873. Thus, it is likely that Gardiner was himself an optician who had relationships with Bendon.

Figure 16.

A stick barometer, signed by J.B. Gardiner. It is 102 cm / 40 inches tall. Adapted from https://www.liveauctioneers.com/item/10417702_a-good-oak-stick-barometer-by-jb-gardiner-bris

Conclusions

Judging from the surviving instruments, the products of James Blake Gardiner were not particularly innovative or expensive, although they were elegant and well crafted. His work as an optician did not leave a significant mark in the history of scientific instruments making. Nonetheless, I do not regret the time I spent in gathering information about this forgotten optician.

To me, an old microscope is more than a contraption made of brass and glass. Regardless its scientific or technical value, it is always the product of skilled craftsmanship and of long hours of labour. Behind each instrument, there is the story of the person who made it. So, an old microscope is also a sort of portal, through which the curious mind can travel in space and time, visiting places and meeting people of the past, in one word: learning.

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to Julian Lea-Jones of the Bristol Science Club for his help in researching Gardiner's business in Bristol. I am also very grateful to Brian Stevenson, curator of the site microscopist.net, for his help and information about John and Thomas D. King. I also thank Oronzo Mauro and Paolo Brenni of the Scientific Instrument Society and Melanie Reedman of the Royal Microscopical Society, for their help in my quest for information about Gardiner's instruments.