S.C. Hincks, of Runfold Lodge, Farnham, Surrey, was a relatively well-off gentleman who became somewhat famous as an artist in his time. He had an interest in microscopy from the 1860s onward, and evidently mounted a fair number of slides of diverse specimens (Figure 1). Hincks also acquired slides by other mounters, and several are known that bear his label as a mark of ownership label (Figure 2). He does not appear to have been a member of a formal microscopy club.

Two slides with Hincks' labels are shown in Brian Bracegirdle's Microscopical Mounts and Mounters, on plates 20-H and 43-P. The handwriting on the label of slide 20-H is that of professional slide-maker Edmund Wheeler (1808-1884). Hincks evidently bought or traded for this slide of strewn diatoms. It was probably that Wheeler slide, with Hincks' ownership label, that led to Dr. Bracegirdle inaccurate characterization of Hincks as a "mounter of diatoms".

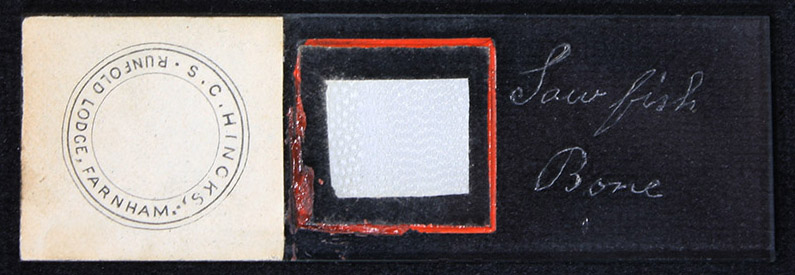

Figure 1.

Microscope slides with S.C. Hincks' labels, dated 1873 and 1877. He probably made both of these slides. From the author's collection or adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Figure 2.

A microscope slide that is attributed to professional slide-maker George Carter (1806-1870), with S.C. Hincks' ownership label.

Figure 3.

Hairs from a "common rat", prepared by S.C. Hincks in 1873 (see Figure 1). Photographed with a 3.5x objective lens, crossed polarizing filters, and a blue-yellow selenite.

Census records indicate that Samuel Charles Hincks was born in about 1829 in Walsall, Staffordshire. His 1852 marriage record states that his father's name was William. Considering those facts, he was probably the Charles Hincks who was baptized on April 10, 1829 at St. Matthew's Church, Walsall, son of William and Mary Hincks. The father's occupation is not known, but the family was relatively wealthy, as the 1841 census shows that 12 year old Samuel Charles was then boarding at a school in Great Barr, Staffordshire.

The 1851 census found S.C. Hincks living near London, in New Cross, Kent. He was living with a relative, Charles Hincks. The census record states that S.C. was Charles' "son", although other records show that this was incorrect. Charles Hincks was an ironmonger, and S.C. was working alongside him. Charles Hincks had been an ironmonger in the London area since at least the 1820s, and was the son of Joseph Hincks, also an ironmonger. Members of the Hincks family are recorded as being ironmongers in Staffordshire during the late 1700. Most likely, S.C and Charles Hincks were distant cousins, and S.C. was sent to London to learn a trade.

The relationship between S.C. and Charles is important because Charles Hincks had two daughters, and S.C. Hincks married the eldest, Mary Ann, in 1852. They may have already been considered common-law spouses by the time of the 1851 census, which may explain S.C. being described as Charles' "son". Charles had a financially successful business, as evidenced by the multiple live-in servants recorded in the censuses, and the estate of some £12 000 that he left upon his death in 1863.

S.C. Hincks likely inherited a considerable portion of Charles' estate through Mary Ann. He may also have received an inheritance from his own father. Notably, the parish record of the marriage of S.C. and Mary Ann listed S.C., his father, and her father as "gentlemen", rather than having jobs. Later records imply that S.C. Hincks probably did not work for a living through the remainder of his life.

Census records from 1861 onward described S.C. Hincks' occupation as "artist". His work was described as "sporting", with a heavy focus on scenes relating to hunting. He exhibited at the British Institution from 1858 onward, displaying oil paintings with titles such as "Deer stalking in the Highlands" and "Pet fawns". His "Hard winter" was described as one of his best, although the same reviewer was also dismissive of the work as art: "A large composition, in which lies a poor doe, starved and frozen to death. The treatment of the subject is not felicitous; the suffering of a hard winter might be described more forcibly by life than by death". I located one photograph of a Hincks painting, of a trained falcon, that he produced in 1860 (Figure 6). It is more an illustration than a work of art, being a rather stilted image that shows what the bird looked like, rather than evoking any sort of emotion. If this is an average example of Hincks' art work, then he was probably a hobby artist, and he almost definitely would not have earned an income that could support his home and other hobbies.

S.C. and Mary Ann initially lived with her father, and their only child, Clara, was born at that home in New Cross. During the late 1850s, they moved to Badshot, Farnham, Surrey. The 1851 census shows that they had a domestic servant. During the 1860s, they moved to Runfold Lodge, Farnham. The 1871 census list two domestic servants.

Bracegirdle's Microscopical Mounts and Mounters shows a slide with an S.C. Hincks label and a date of 1860 (Plate 43-P). Hincks may have made that slide himself. He seems to have peaked in enthusiasm for microscopy during the 1870s. In 1872, he offered to provide Lepisma saccharina to interested persons (Figure 4). The scales from that insect (a silverfish) were commonly used as microscope test objects. It is not clear whether S.C. proved whole insects or mounted scales. His 1876 offer to exchange rhubarb, "beautifully showing spiral vessels and raphides", undoubtedly meant prepared microscope slides.

Hincks also sent a couple of microscopy hints to Hardwicke's Science-Gossip (Figure 5). He republished his tip on Scotch Fir sap crystals in 1889, in The Journal of Microscopy and Natural Science. That was the official journal of the Postal Microscopical Society, but it is not known whether Hincks was a member of the PMS.

An indication of the size of Hincks' Runfold Lodge estate was provided by an 1876 for a professional gardener to manage the Hincks' kitchen garden and greenhouse. They offered wages plus a cottage to live in (Figure 7).

In addition to microscopy and painting, records indicate that S.C. Hincks enjoyed several other pastimes. A bloodhound that he bred in 1872, named "Norma", won second prize at a dog show at the Crystal Palace. He was reported to have raised kestrels in his aviary. In 1893, he displayed his collection of "a series of palaeolithic implements" to visitors from the Geologists' Association. He donated a significant number of live, wild animals to the menagerie of the Zoological Society of London, including a wood owl (Syrnium aluco) in 1874, two greater spotted woodpeckers (Dendrocopus major) and three long-eared owls (Asio otus) in 1883, and a pair of corn crakes (Crex pratensis) in 1887.

S.C. Hincks died on June 21, 1894 at his Runfold Lodge home, leaving an estate with a value of over £8000. The 1901 census shows that his widow, Mary Ann, still lived at Runfold Lodge, supported by a cook and a domestic servant.

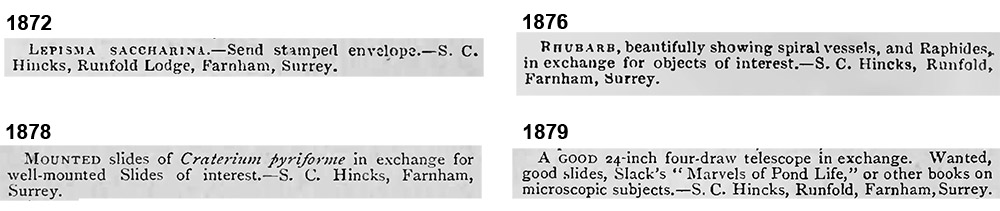

Figure 4.

Exchange offers that S.C. Hincks published in "Hardwicke's Science-Gossip".

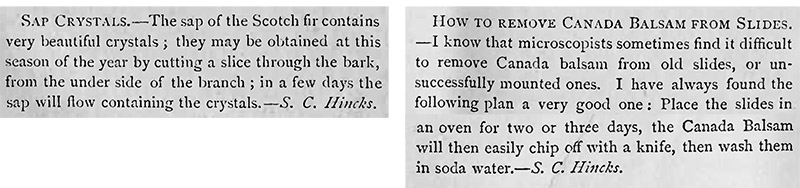

Figure 5.

Hints for the microscope, sent by S.C. Hincks to "Hardwicke's Science-Gossip" in 1878 (left) and 1879 (right).

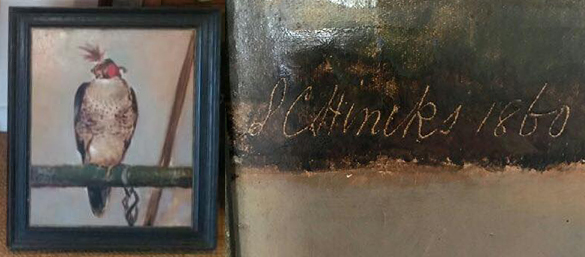

Figure 6.

S.C. Hincks, photographed during the early 1870s. In 1874, The Postal Microscopical Society requested that all members provide a photograph of themselves, which were then used to produce a collage to be distributed as a way of “introducing” members to each other.

Figure 7.

Painting and signature of S.C. Hincks' 1860 picture of a falcon named "Duchess". The bird was raised and trained by John Pells (1815-1883), a noted falconer. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from the British Archives of Falconry Facebook Page, https://www.facebook.com/groups/611660562249213/permalink/1890262297722360/

Figure 8.

An 1876 advertisement that gives insight on life at the Hincks' Runfold Lodge.

Resources

The Art Journal (1860) The British Institution, pages 77-78

Bracegirdle, Brian (1998) Microscopical Mounts and Mounters, Quekett Microscopical Club, London, pages 52, 144, and 190, and Plates 20-H and 43-P

England census and other records, accessed though ancestry.com

The Gardeners' Chronicle (1876) Advertisement from S.C. Hincks, page 414

Graves, Algernon (1901) The British Institution, 1806-1867: A Complete Dictionary of Contributors and Their Work from the Foundation of the Institution, G. Bell & Sons, London, pages 270-271

Hardwicke's Science-Gossip (1872) Exchange offer from S.C. Hincks, Vol. 8, page 144

Hardwicke's Science-Gossip (1876) Exchange offer from S.C. Hincks, Vol. 12, page 48

Hardwicke's Science-Gossip (1878) Exchange offer from S.C. Hincks, Vol. 14, page 96

Hardwicke's Science-Gossip (1879) Exchange offer from S.C. Hincks, Vol. 15, page 48

Hincks, S.C. (1878) Sap crystals, Hardwicke's Science-Gossip, Vol. 14, page 88

Hincks, S.C. (1879) How to remove Canada balsam from slides, Hardwicke's Science-Gossip, Vol. 15, pages 61-62

Hincks, S.C. (1889) Scotch fir, The Journal of Microscopy and Natural Science, Vol. 8, page 190

The Kennel Club Calendar and Stud Book (1876) Bloodhounds, Vol. 4, page 55

List of the Vertebrated Animals Now or Lately Living in the Gardens of the Zoological Society of London (1883) pages 291 and 355

Marriage record of Samuel Charles Hincks and Mary Ann Hincks (1852) Parish records of St. Paul's Deptford, accessed through ancestry.com

Morris, Francis Orpen (1895) History of British Birds, J.C. Nimmo, London, page 110

Nature (1887) Additions to the Zoological Society's Gardens, Vol. 36, page 308

Post Office London Directory (1843) "Hincks Charles, who. ironmonger, 13 Creed la., Ludgate st", page 228

Probate of the Will of Samuel Charles Hincks (1894) "Hincks Samuel Charles of Runfold lodge Farnham Surrey gentleman died 21 June 1894 Probate London 13 July to Mary Ann Hincks widow Effects £8236 8s 9d", accessed through ancestry.com

Proceedings of the Geologists' Association (1893) Excursion to Farnham, pages 74-81

Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London (1874) Donations, page 692