Louis-Jacques Laporte, 1894 - 1978

by Brian Stevenson

last updated April, 2024

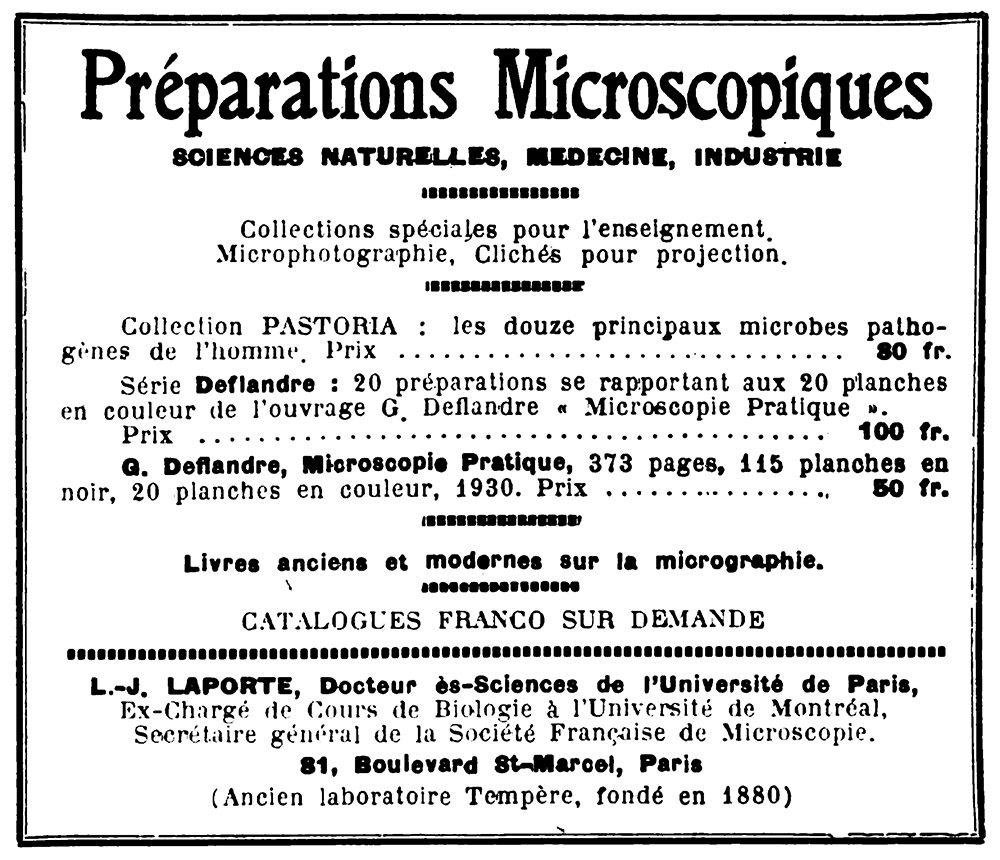

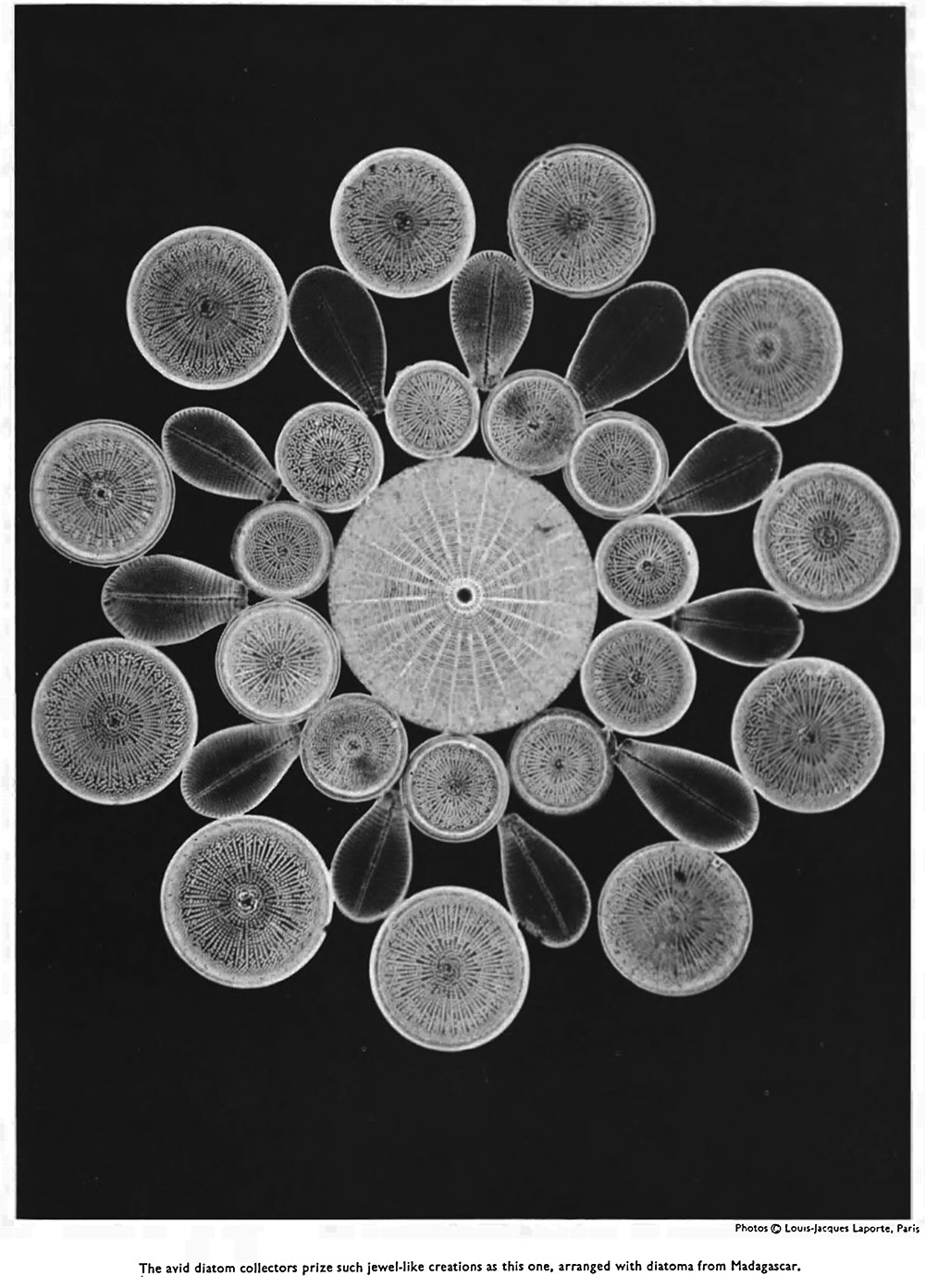

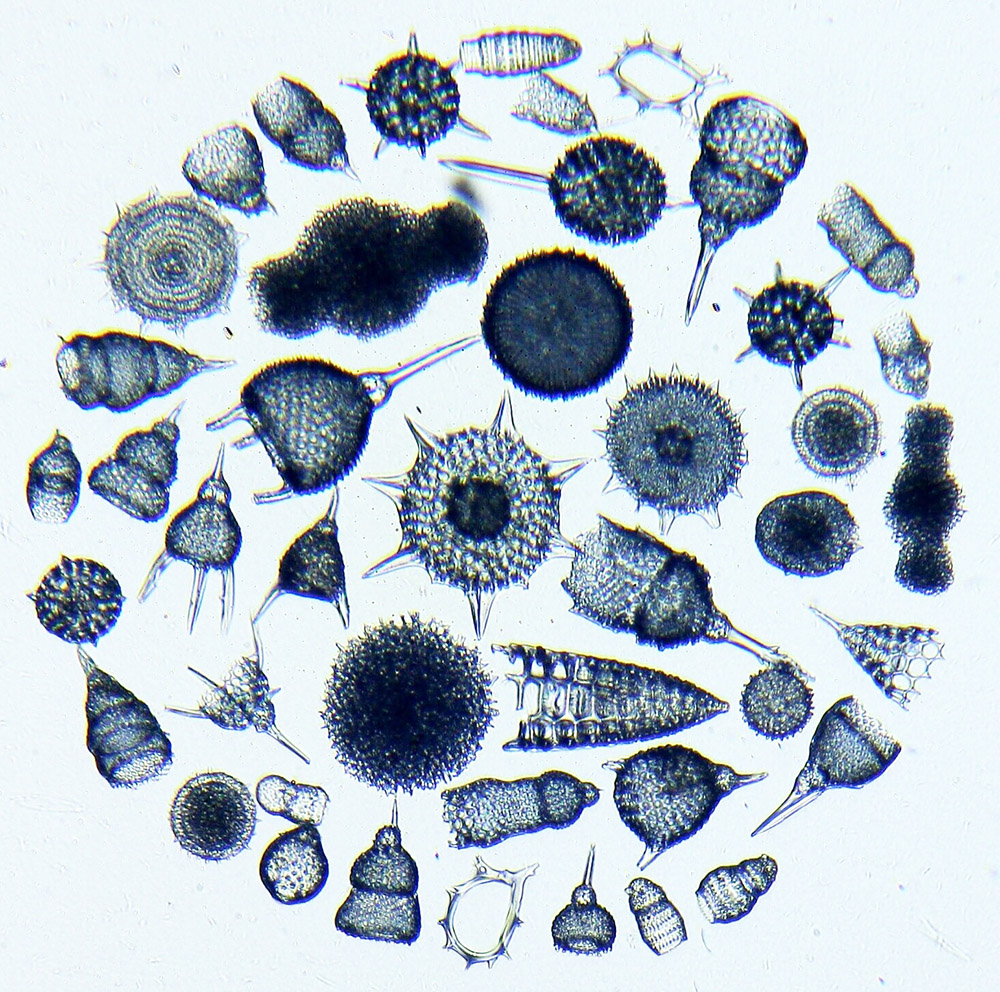

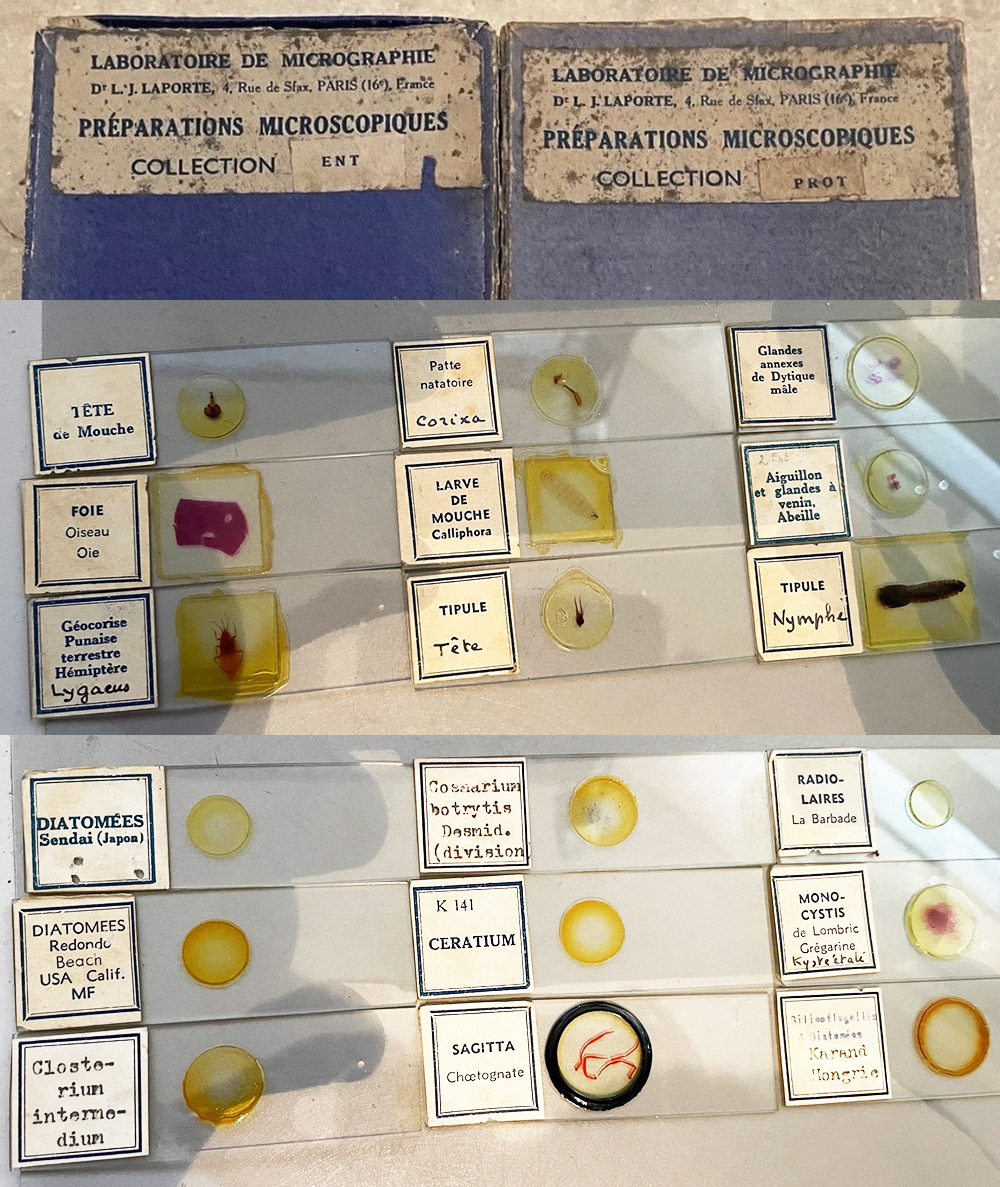

L.J. Laporte was a professional maker of microscope slides, based in Paris, France. He studied microscopy in his youth, and, from 1921 until ca. 1928, taught microscopy at the University of Montreal, Canada. He returned to Paris around 1928 and began his slide business. He acquired the stock of diatomist J.C. Tempère (1847-1926) and evidently sold those slides with his own labels (Figures 1 and 2). Laporte developed skills to arrange diatoms and other microscopic objects into artistic designs, as well as techniques for mounting a wide variety of other materials (Figures 1, 3, 4, and 10). By 1961, he was France’s leading supplier of educational slides and photomicrographs to universities and schools.

Figure 1.

Microscope slides from L.J. Laporte, which can be dated by Laporte’s address or style (see below). The top slide, from ca. 1929, was probably made by J.C. Tempère (1847-1926), whose stock of slides was acquired by Laporte. Adapted by permission of C. Downing or for nonprofit, educational purposes from internet auction sites.

Figure 2.

Selected Epithemia gibberula diatoms (see Figure 1). Imaged with a 40x objective lens and C-mounted digital SLR camera on a Leitz Ortholux II microscope.

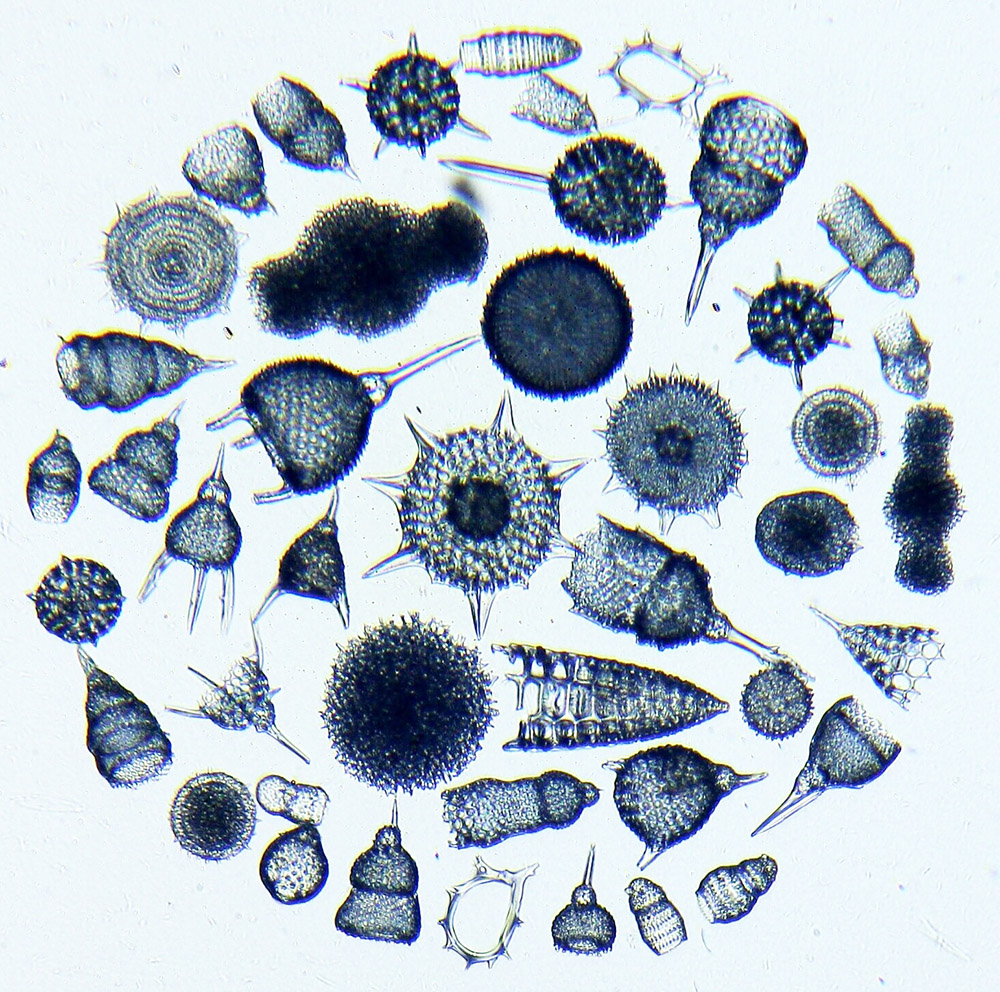

Figure 3.

Arranged radiolarians by L.J. Laporte, ca. 1934 (see Figure 1). Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

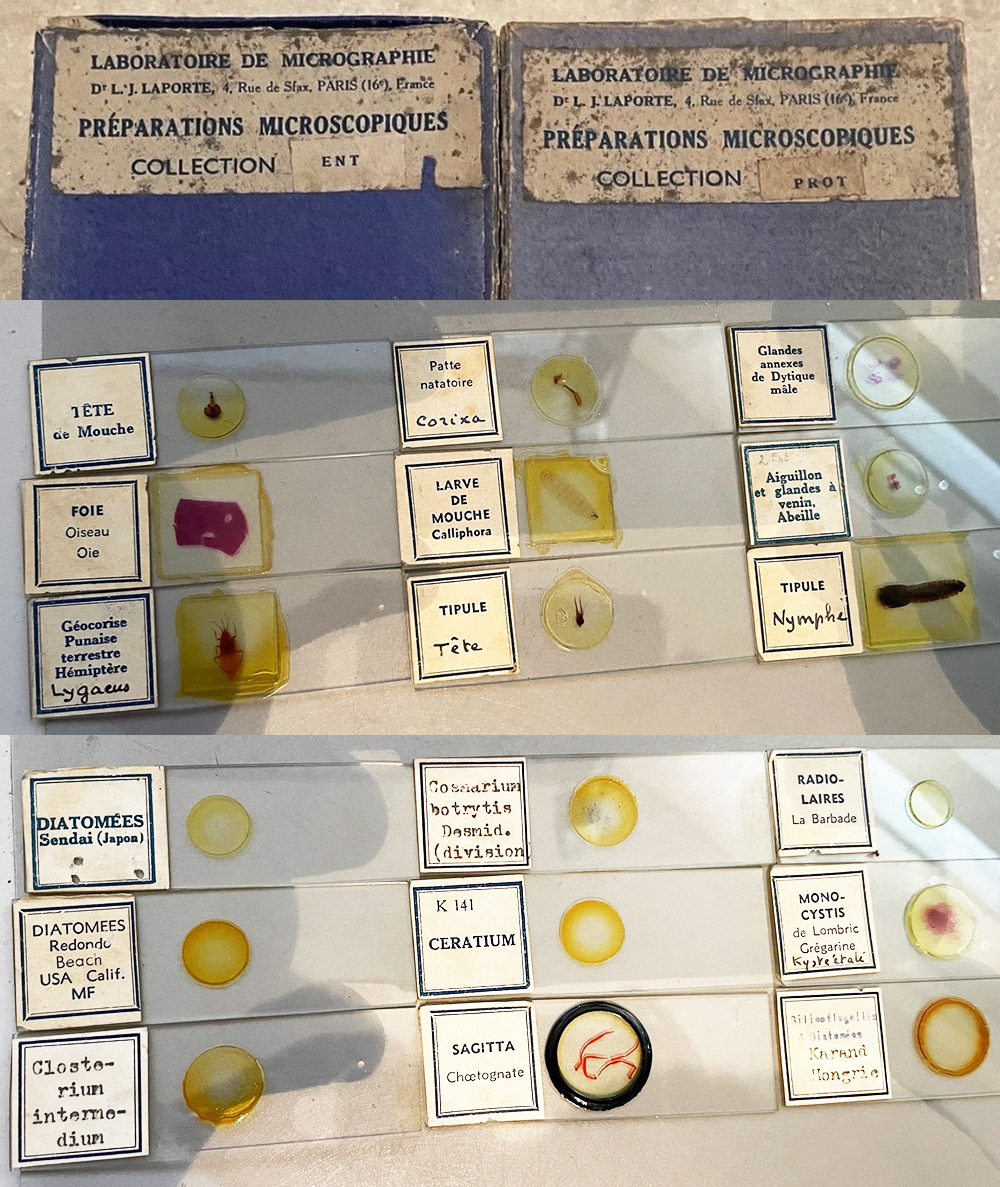

Figure 4.

ca. 1960s microscope slides and boxes by L.J. Laporte. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Figure 5.

Box of 35mm slides by L.J. Laporte, ca. 1960s. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://inventaire.patrimoines.laregion.fr/dossier/IM46106604.

As of yet, very few records of Louis-Jacques Laporte’s personal life have been identified. He was born in Paris on June 7, 1894. His father, also named Louis, was a lumber merchant.

Our microscopist was 18 years old when World War 1 began, and very likely served in the French military. His elder brother, André, a promising musical composer, was killed in 1918.

Laporte received a university education. A 1961 interview mentioned that “he sold sketches of the Luxembourg Gardens in the Latin Quarter to help pay his way through the Sorbonne”. This likely referred to before 1921, after which his income would have been more substantial.

In 1921, Laporte moved to Canada to teach microscopy at the University of Montreal. He arrived in that country on December 9, 1921, when he would have been 25 years old. He remained there until ca. 1928, except for a 4 month vacation in Paris during 1924. The Naturalists’ Directory for 1929 listed Laporte as “Dir. Micro. Lab., 20 Hutchinson St., Montreal, P.Q., Mic.”

He probably returned to Paris during 1928, based on a catalogue with that date. The Naturalists’ Directory for 1929 included an advertisement from Laporte, which gave his address as 9 Rue St. Romain, Paris (Figure 6).

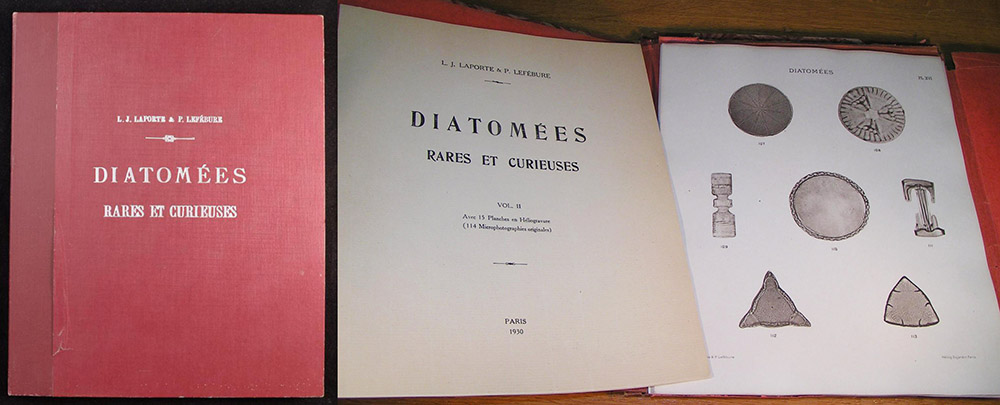

He and diatomist P. Lefébure published a two-volume book in 1929-30, entitled Diatomées Rares et Curieuses (Figure 7). A review in Watson’s Microscope Record sheds important light on Laporte’s business: “The authors of this book have all the diatomaceous material left by the late J. Tempère, and have evidently made a very careful study of such an extensive collection. This first volume contains fifteen plates, on which are reproduced by the heliogravure process about two hundred photomicrographs. Many of the species have never been shown in any previous publication and the illustrations cannot fail to interest every student of the diatomaceae. The text is, of course, in French and gives the necessary information about species, origin, magnification and bibliography.” Hence, Laporte had acquired the stock of J.C. Tempère (1847-1926). He undoubtedly made good use of Tempère’s raw material for preparing his own slides. The top slide shown in Figure 1, above, strongly resembles Tempère’s work, and was probably made by Tempère and relabeled by Laporte.

According to Brian Bracegirdle, a 1928 catalogue from Laporte “contains a good selection of human histology, and an especially full section on human histopathology. These slides were made by Dr. C. Oberling at the University of Strasbourg, and were mostly Masson stained. The bacteriology section included most organisms, with a variety of up-to-date stains. A small group of slides made from a three-month human embryo complete this remarkable list.”

Laporte joined the Société Botanique de France in 1930. He had been a member of the Société Scientifique d'Arcachon since at latest 1925. By 1932, he was General Secretary of the Société Française de Microscopie.

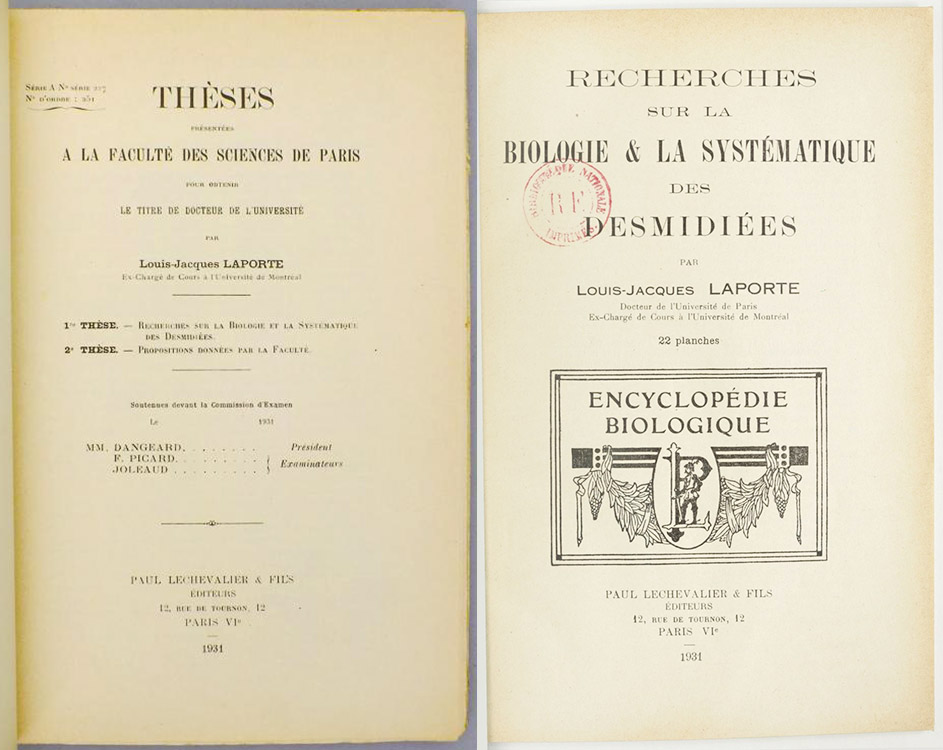

Laporte received a doctorate degree in 1931 from the University of Paris. That year, he also published his doctoral thesis as a book, Recherches sur la Biologie et la Systématique des Desmidiées (Figure 8).

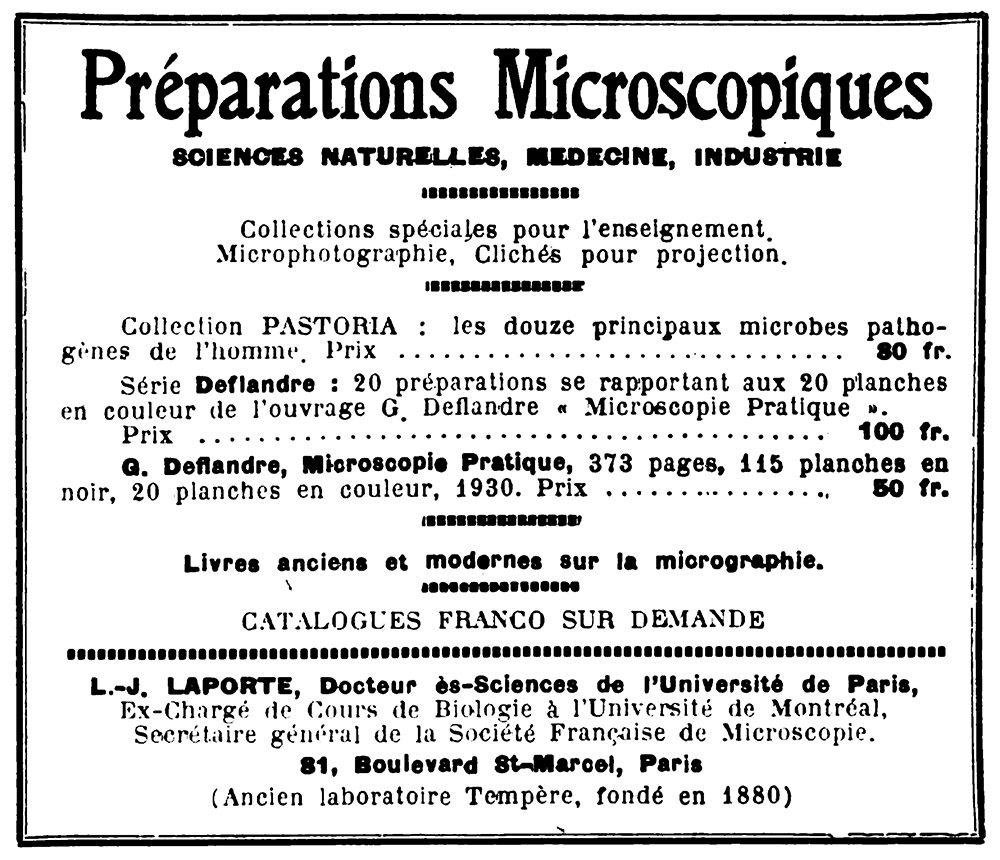

A 1932 advertisement indicated that Laporte had moved his business to 81 Boulevard St. Michel, Paris (Figure 9). It also desribed the business as “Ancien laboratoire Tempère, fonde en 1880”. This claim to connection with Tempère was certainly hyperbole. I have no records of Tempère working or living at 81 Boulevard St. Michel. Tempère began selling slides of diatoms and other materials around 1879, when he lived in England, and did not return to his home country of France until 1884. He left Paris in 1902, moving to Grez-sur-Loing, Siene et Marne, and later to Arcachon, near Bordeaux.

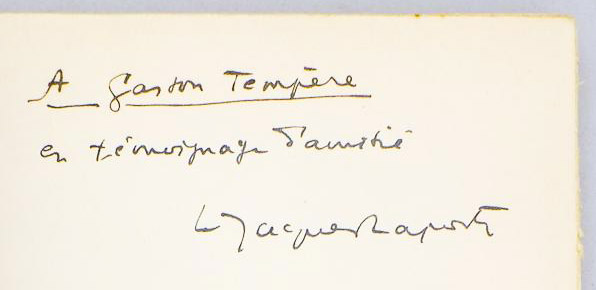

It is possible that Laporte knew J.C. Tempère to some extent, perhaps in connection with purchasing his slides and mounting material. A copy of Laporte’s Ph.D. thesis is known with a handwritten dedication to J.C. Tempère’s son, Gaston (Figure 10). Also of note, Laporte was a member of the Société Scientifique d'Arcachon, where the Tempère family lived, even though Laporte lived in Paris. Perhaps Laporte studied with or worked for J.C. Tempère at some time?

By 1934, Laporte had moved again. That year’s list of members of the Société Botanique de France gave his address as 4 Rue de la Sorbonne. The third slide in Figure 1 shows that address.

Laporte’s slide-making business became “the leading supplier of microscopic slides” for universities and other schools, along with individual sales to students. This included both slides for use with a microscope and photographic prints and projector slides (Figures 4-5). A 1961 article noted that the business “keeps him busy seventy-two hours a week”. During the morning interview that formed the basis of that article on Laporte, he was “interrupted occasionally by the doorbell announcing students who needed slides for an experiment or a thesis”. As the morning wore on, “the doorbell in the musty old office housing these micro-marvels was now beginning to ring more insistently”.

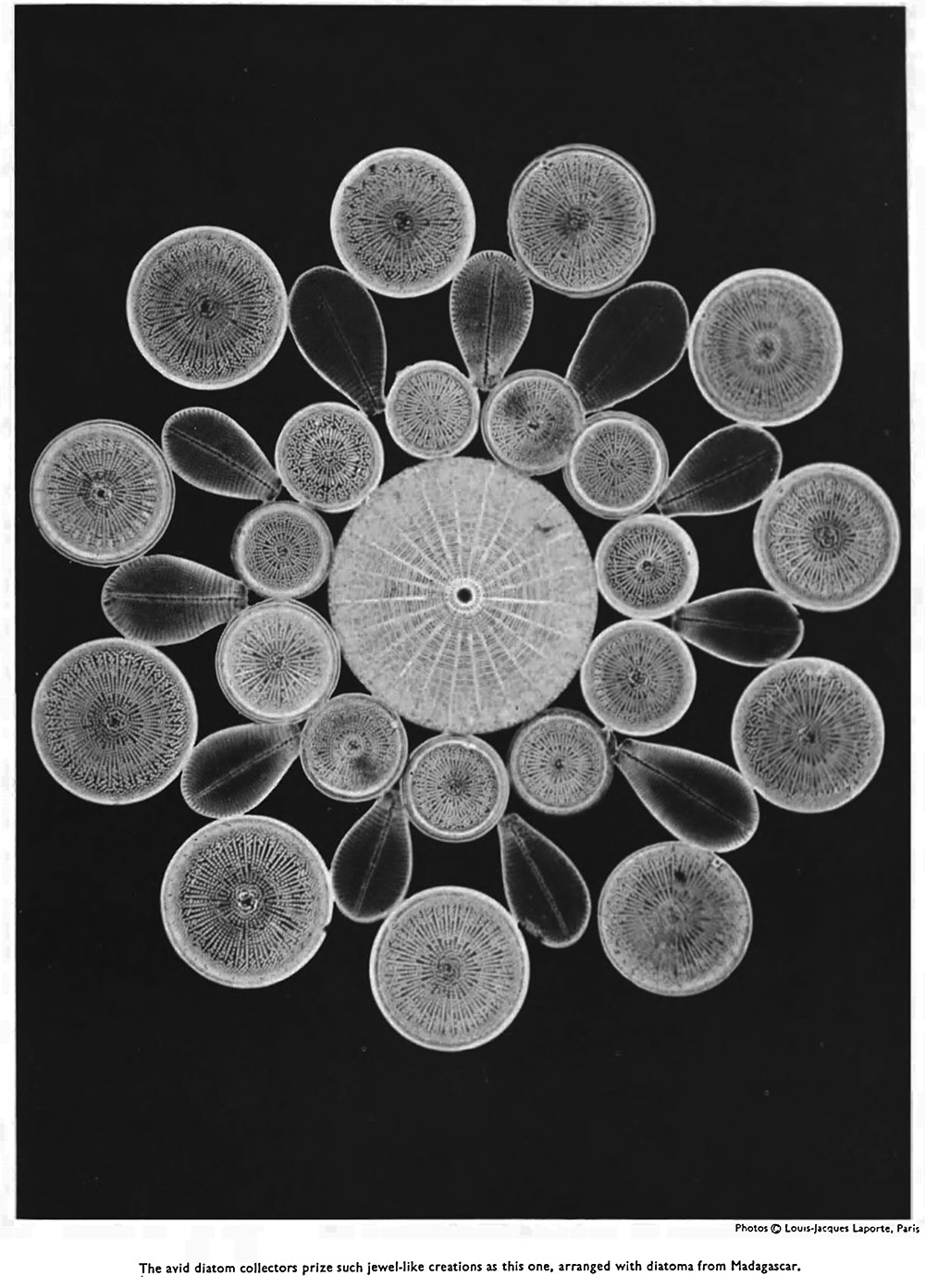

He also continued to produce slides of diatoms and similar items, as strews, selected specimens, and artistic arrays (Figures 3 and 10). During his 1961 interview, Laporte read a letter from “a French priest in La Havre” who wanted a “diatom rose-window”, stating, “what is important to me is the beauty of the slide. You known that I am very demanding. You have my entire confidence.” Laporte commented “I only get about one a year like this nowadays ... There you have a vanishing race – the diatom collector.”

The 1961 article described Laporte’s home/business, which was probably similar to his previous locations (he had since moved to 4 Rue de Sfax): “Roll-top desk, a huge table covered with scarred linoleum and assorted flasks, bottles, and papers, a gas radiator which has the habit of turning itself on and off with disconcerting pops, and files, files, files climbing the walls to the ceiling. Adjoining this office is another room containing the simple stand used for microphotography, hundreds of photographs and more files filled with microscopic slides. There is also a kitchen, converted into a warehouse, whose contents include a few boxes of carefully labelled sacks of earth from Barbados, brough back after an expedition two years ago in search of new specimens of diatoma.”

Laporte himself was described as “a mild, distinguished-looking man who wears a discreet rosette of the French Legion of Honour in his lapel ... He is not only a scientist and a photographer, but he also happens to be a singer (he is president of one of Paris’s leading choral societies), a writer, and a painter. True, he hasn’t done very much painting since he sold sketches of the Luxembourg Gardens in the Latin Quarter to help pay his way through the Sorbonne, but he has been writing all his life. Among his books are ‘The Invisible World’, ‘What You Should Know About the Microscopic World’, a collection of poems entitled ‘Souls and Landscapes’, and a detective story. Yet it might be said that all of his talents – even a musician’s sense of harmony – met in one of his most recent works, ‘Panorama of the Micro-World’. Here, as he explained to us in his laboratory, art took precedence over science. Its 300-odd illustrations from his own collection of micro-photographs and other equally rich collections are a gallery of portraits, landscapes, vignettes and non-figurative compositions.”

Louis-Jacques Laporte died on August 31, 1978, in Fontainebleu.

Figure 6.

Advertisement from the 1929 “Naturalists’ Directory”. Laporte’s address was then 9 Rue St. Romain, as is also seen on the top slide in Figure 1, above.

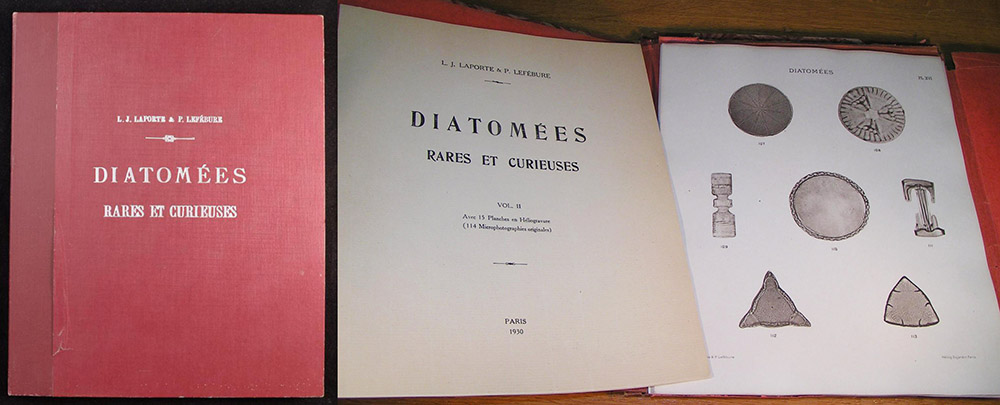

Figure 7.

Cover and insides of a volume of Laporte and Lefébure’s 1929-1930 two-volume “Diatomées Rares et Curieuses”. The books include photographs and descriptions of rare diatoms that they found in the collection / business stock of J.C. Tempère. Images adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from internet retail sites.

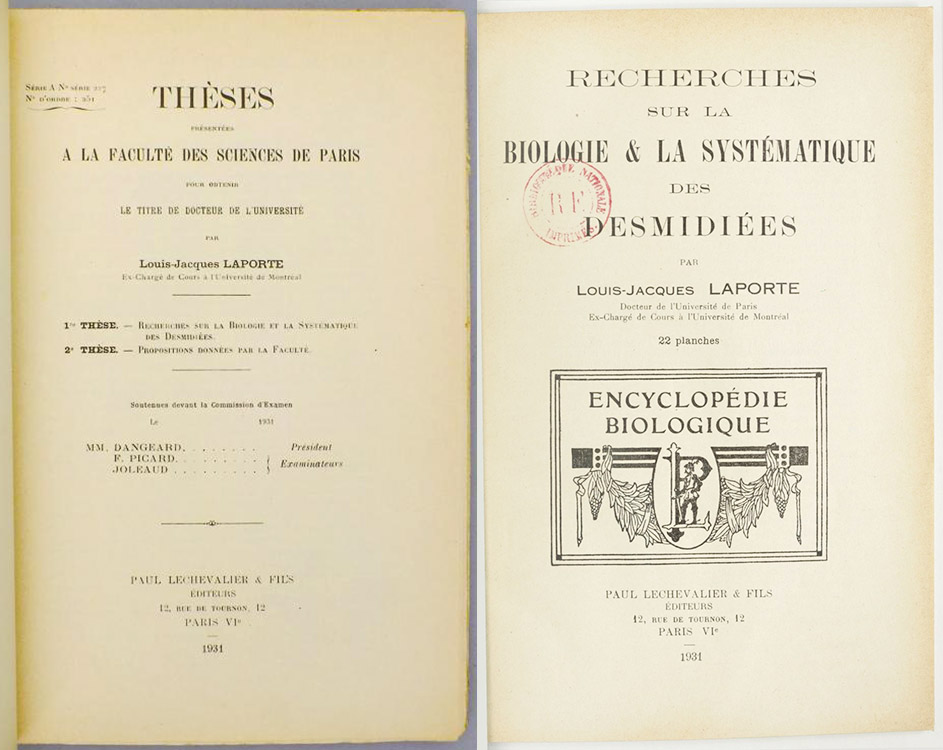

Figure 8.

Title page of Laporte’s 1931 Ph.D. thesis, and of the subsequent book “Recherches sur la Biologie et la Systématique des Desmidiées”. Images adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6382219j.texteImage and an internet retail site.

Figure 9.

1932 advertisement from “Bulletin de l’Union des Naturalistes”.

Figure 10.

Dedication of a copy of L.J. Laporte’s 1931 Ph.D. thesis to Gaston Tempère, son of J.C. Tempère. This makes it clear that Laporte knew the Tempère family. Image adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet retail site.

Figure 11.

Photograph of an arrangement of diatoms – both the slide and the photograph were produced by L.J. Laporte. From “Microscopy Reveals the Invisible World”, 1961.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Howard Lynk and Craig Downing for sharing information and images.

Resources

Acte de décès à Fontainebleau (77300) pour l'année 1978 (accessed April, 2024) “Louis Laporte (Louis Jacques Laporte) died on 31 August 1978 at the age of 84 and born in Paris 20th arrondissement on 7 June 1894. Act No. 414”

Behrman, Daniel (1961) Microscopy reveals the invisible world, UNESCO Courier, pages 20-27

Bracegirdle, Brian (1998) Microscopical Mounts and Mounters, Quekett Microscopical Club, London, page 61

Bulletin de l’Union des Naturalistes (1932) advertisement from L.J. Laporte, page 57

Canadian and USA entry records for Louis-Jacques Laporte (1924) acquired through ancestry.com

Laporte, Louis-Jacques (1931) Recherches sur la Biologie et la Systématique des Desmidiées, accessed through https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6382219j.texteImage and https://www.livre-rare-book.com/book/5472636/31124

The Naturalists' Directory (1929) advertisement from L.J. Laporte

The Naturalists' Directory (1929) page 195

Our Senses and the Knowledge of the World (1951) acknowledgement: “Docteur Laporte, 4 rue de Sfax, Paris (France), who has lent a collection of microscope preparations of embryology”, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, Paris, page 66

Rome Prize, 1910-1919 (accessed April, 2024) André Laporte (1889 - 1918), http://www.musimem.com/prix-rome-1910-1919.htm

Société Botanique de France Liste des Membres (1934) “1930. Laporte (Louis-Jacques), biologiste-micrographe, ex-chargé de Cours, à l'Université de Montréal, rue de la Sorbonne, 4, à Paris, ve”

Société Scientifique d'Arcachon, Station Biologique, Compte Rendu Administratif (1925) page 10

Watson's Microscope Record (1929) Diatomées Rares et Curieuses, page 18