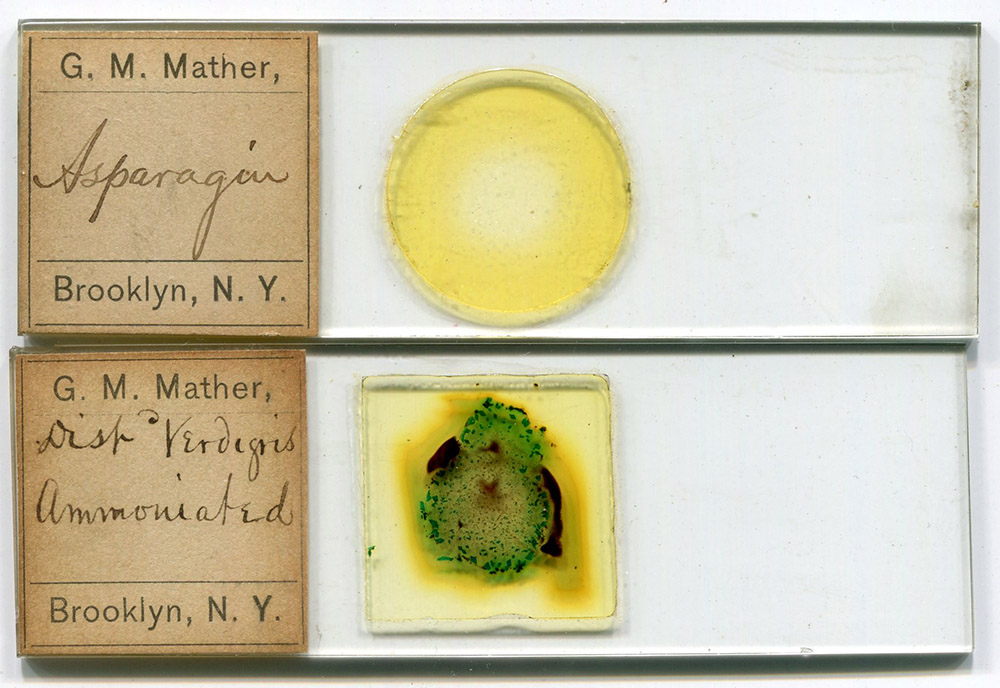

Figure 1. Microscope slides of chemical crystals, prepared by G.M. Mather. His address of Brooklyn dates them to between ca. 1880 to 1891 or between 1897 until his death in 1914.

George Messenger Mather, 1833 - 1914

by Brian Stevenson

last updated April, 2025

Amateur microscopist George M. Mather was especially interested in chemical and mineral crystals, preparing fine-quality slides of crystalized chemicals and mineral micromounts. He worked as an insurance agent. Mather lived for most of his life in Brooklyn, New York, with a six year break from 1891 until 1897 in Passaic, New Jersey. Mather was a long-standing member and frequent officer of the Microscopy and Mineralogy departments of the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences.

Figure 1.

Microscope slides of chemical crystals, prepared by G.M. Mather. His address of Brooklyn dates them to between ca. 1880 to 1891 or between 1897 until his death in 1914.

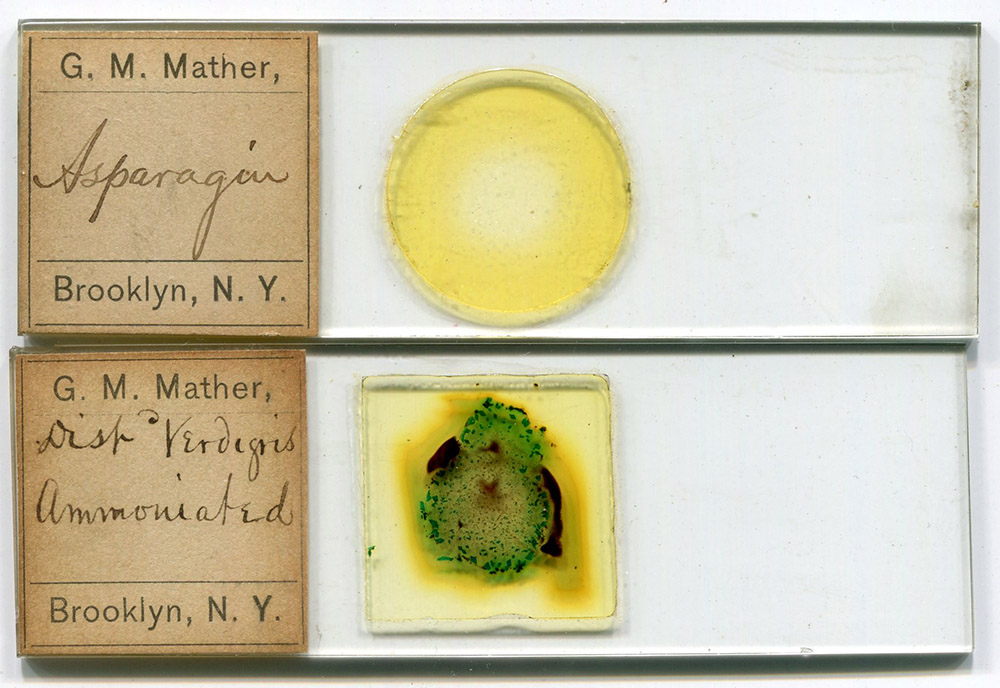

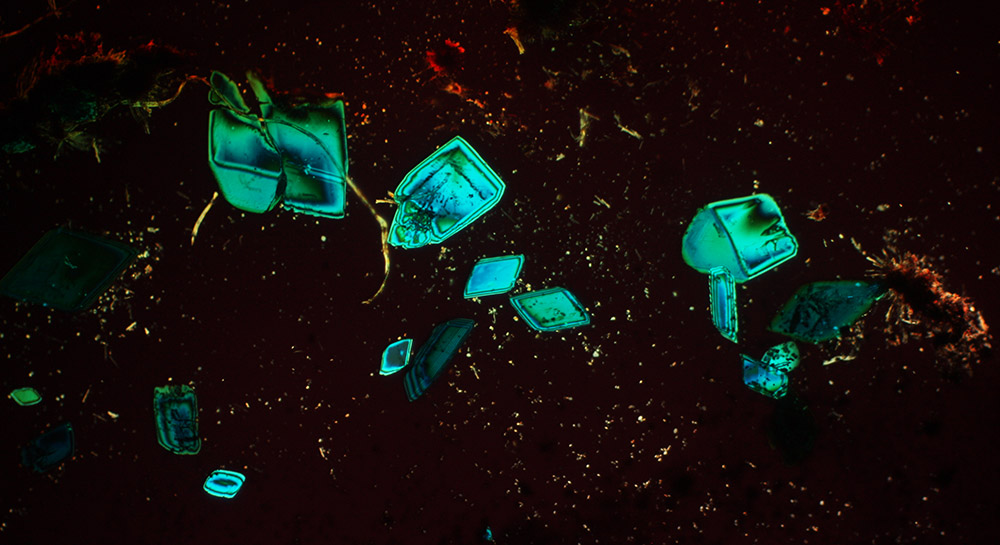

Figure 2.

“Distilled Verdigris, Ammoniated” (copper acetate that was treated with ammonia), by George M. Mather (see Figure 1). Images with a 10x objective lens and C-mounted digital camera with crossed polarizing filters on a Leitz Ortholux II microscope.

George Messenger Mather was born on October 5, 1833, in Darien, Connecticut, son of son of George and Mary Ann (née Whitney) Mather. Census records indicate that the father worked as a “merchant”.

Young George left home as a teenager, with the 1850 national census showing him working in Manhattan, New York as a book keeper. He boarded along with an older brother, Charles.

Mather evidently did well in his career. He married Sarah Clowes on May 5, 1859. The 1860 census recorded that George, Sarah, two children, and Sarah’s widowed mother lived in Manhattan with a domestic servant.

The US Civil War broke out in 1861. George Mather joined the 28th Connecticut Infantry of the US Army in September, 1862. His regiment served in Louisiana, most notably taking part in the conquest of Port Hudson on the Mississippi River during the summer of 1863. Mather was mustered out after that battle on August 23, 1863, with the rank of First Sergeant.

Mather returned home to his family in New York, settled in Brooklyn, and resumed his book keeping.

It is unclear when or why Mather became interested in microscopy. He was a member of the Brooklyn Microscopical Society before 1887. A report of the Society’s 1887 Annual Reception noted that Mather’s exhibition of “globules of mercury sublimed” deserved “special mention”.

Further details on the Brooklyn Microscopical Society’s 1887 Annual Reception: “This Society, organized in 1880, has grown to be one of the most flourishing associations in the State. Its object has been comparison of work and methods by informal methods, at bi-monthly meetings, rather than the discussion of set topics and papers. It numbers about seventy-five members, and includes all the prominent scientists, physicians, and amateurs in Brooklyn. On Tuesday evening, April 19, a reception was given at the hall of the Adelphi Academy, and a throng of ladies and gentlemen accepted the invitations. Sixty-eight microscopes were arranged on tables in the spacious hall of the Academy. The instruments were numbered and the catalogue informed the observer of the object and exhibitor. The exhibits bore testimony to the care of preparation, as well as the skill in instrumental manipulation and illumination by the members, and the selection of slides by the committee in charge does them credit.”

The Brooklyn Microscopical Society joined with the Brooklyn Institute in 1888, forming the Department of Microscopy. Mather then served as the department’s Vice President.

A report of the 1889 Reception is especially interesting, as the microscopes were lit by electric light for the first time: “The annual reception of the Department of Microscopy of the Brooklyn Institute occurred on Thursday, May 9. There were in position more than 50 microscopes, each arranged to exhibit an object of interest. These microscopes were placed on six long tables, each table provided with three incandescent lamps supplied with a current from Mr. E.R. Knowles’ patent storage batteries, furnished for the occasion by the Mutual Electric Manufacturing Co., of Brooklyn. The lamps were maintained during the entire evening at a high state of incandescence, giving a very white light, well adapted for the display of microscopic objects, particularly those requiring the polariscope. The yellow hue so familiar to those in the habit of using kerosene lamps was entirely wanting. Besides this advantage, there was an absence of heat: the lady visitors could view the objects without fear of burning their hats, a common occurrence when lamps were used. A rare opportunity was afforded to several hundred interested spectators to see in an hour more of the minute wonders of nature and art than they would be liable to see in a lifetime but for such an occasion as this. The following is a list of objects exhibited … Mr. George M. Mather, vice-president of the section, exhibited the elytron of diamond beetle, showing the gem-like scales, which present all of the colors of the spectrum in great brilliancy. The same exhibitor showed natural crystals of malachite and azurite. These are ores of copper which are found associated in Arizona copper mines.”

In 1891, Mather moved to Passaic, New Jersey, advancing in the insurance brokerage field. He was obviously well-known in local society, in that his relocation was announced in the periodical Brooklyn Life, “Mr. George M. Mather, who has an expensive hobby for gems, and has shown a number of them at the exhibitions in the Brooklyn Institute, is about to leave Brooklyn and put up with the mud, mosquitoes and malaria in New Jersey, in the belief that he is going to have more earth and more air over there than he could get in Brooklyn”.

Mather and family returned to Brooklyn in 1898. During that year, he presented the Brooklyn Institute with “Twenty-five slides of mineral and geological subjects; twenty-nine unmounted photographs of microscopical views of zoological subjects; twenty-three lithograph reproductions of microscopical views taken for the U. S. Geological Survey”.

As far as I can tell from records, Mather remained a member of the Brooklyn Institute’s Microscopy and Mineralogy Departments throughout the remainder of his life. He died on March 11, 1914, and was buried in the Mather family plot in Darien, Connecticut.

Resources

The American Monthly Microscopical Journal (1887) Brooklyn Microscopical Society, pages 97-98

Brooklyn, New York City Directory (1867) “Mather George M. bookkeeper, h 141 Franklin av”, page 355

Brooklyn, New York City Directory (1890) “Mather George M. cashier, h 260 Franklin av”, page 754

Brooklyn, New York City Directory (1898) “Mather Geo. M. ins. h 527 Throop av”, page 918

Brooklyn Life (1891) Mr. George M. Mather, Vol. 3, March 28 issue, page 17

Find a Grave (accessed April, 2025) George Messenger Mather, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/14972718/george-messenger-mather

Passaic City, New Jersey Directory (1891) “Mather George M., cashier N.Y., h 53 Howe ave”, page 106

Patterson City, New Jersey Directory (1897) “Mather George M. insurance, 124 Market, h Passaic NJ”, page 496

Scientific American (1889) Department of Microscopy, Brooklyn Institute, Vol. 60, page 305

US census and other records, accessed through ancestry.com

Yearbook of the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences (1899) Vol. 11, pages 214-215