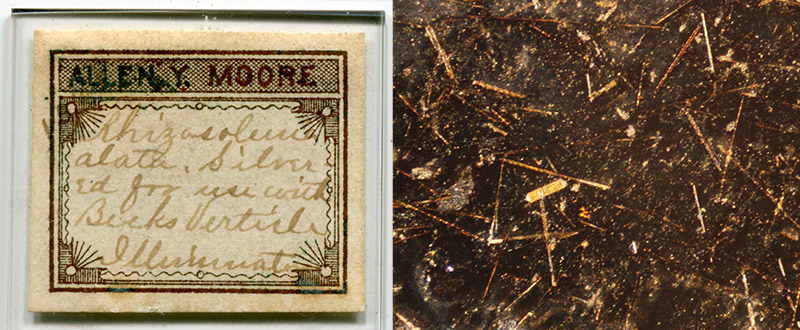

Figure 1. Two microscope slides of diatoms, prepared by Allen Y. Moore. The slide on the left is a dry mount, and that on the right is a silver-coated mount (see Figure 2).

Allen Y. Moore, 1860-1887

by Brian Stevenson

last updated February, 2023

Although he died before his 27th birthday, Allen Moore made a large impact on the American microscopist community. The son of an army officer, he was constantly moved from post to post throughout his childhood, and had little formal education during that time. Nonetheless, Moore evidently found opportunities to educate himself. His first publication on microscopes was written when he was but sixteen years old. Shortly after Moore received his M.D. degree from the Cleveland Homoeopathic Hospital College, he was appointed to the college’s Chair of Microscopy and Histology. In that position, he became a renowned expert in microscopical diagnosis. In addition, Moore prepared a wide variety of microscope slides, which he widely exchanged and sold (Figure 1). Most notably, he mounted diatoms in silver, which enhanced features of the frustules (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Two microscope slides of diatoms, prepared by Allen Y. Moore. The slide on the left is a dry mount, and that on the right is a silver-coated mount (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Silver-coated diatoms, a strew of Rhizosolenia alata (with at least one other form present). As noted on Moore’s label, the preparation was intended for use with Beck’s Vertical Illuminator and a high-power lens. That device allowed light to shine directly down onto the specimen, through the objective lens. With it, and a slide such as this, Moore was able to write, “even Rhizosolenia alata, yields transverse lines, which, so far as I know, have never been seen by any other method”. The image on the right was photographed with a standard 10x objective lens and side-lighting – it was impossible to illuminate with a higher magnification objective (note to self: we need to acquire a vertical illumination apparatus).

Figure 3.

Two types of Beck vertical illuminators.

Left, a drawing of an 1885 improved form, having a moveable adjustment over the aperture, through which to regulate light entering the apparatus.

Right, an extant simpler form, adapted from http://www.microscope-antiques.com/beckvertill.html. Viewed from an end, the reflective cover slip is seen, mounted on a knob that permits the user to adjust the angle of light.

Allen wrote of the Beck vertical illuminator in 1884: “There is no piece of accessory apparatus better adapted to bring out the qualities of our better class of homogeneous immersion objectives than Beck's (or some analogous form of) Vertical Illuminator. Its principle is simple enough: A short tube screws between the nose of the body and the objective. In one side of this tube is a hole - generally about a quarter of an inch in diameter - to admit a beam of light upon a piece of thin glass placed diagonally in the tube and so mounted that a rotating movement can be given to it. When the light strikes this piece of glass it is reflected downwards, into the back lens of the objective, and after successive refractions is brought to a focus upon the object. Thus it will be seen that the objective is its own achromatic condenser, and as the quality of the condenser is the same as that of the objective, a condensation of light takes place which is far superior to that given by the best substage condensers made; for the majority of substage condensers, although they may be of exceedingly wide aperture, are not corrected for chromatism and sphericity to the extent required in first class objectives. Upon the side of the short tube, which contains the thin glass reflector - that is the mounting of the Vertical Illuminator, is generally placed some kind of diaphragm for the purpose of regulating the amount of light admitted to the glass reflector and to confine that which is admitted to certain parts of the glass surface. For if the light be admitted in a narrow beam only, on to the central part of the reflector and be then reflected downwards to the back lens, it will strike this lens in the middle and will finally reach the object as more or less central light. But if it be admitted to the edge of the reflector it will then pass through the edge of the back lens, and when it reaches the object will be an oblique ray to the extent of half the angular aperture of the objective. When admitted through the entire opening, the light will reach the object as a cone whose angular breadth will correspond with that of the whole angular aperture of the objective”.

Allen Y. Moore was born on July 12, 1860, near San Diego, California. His father, Orlando, was then a Lieutenant in the U.S. Army. The U.S. Civil War broke out the following April. From then through 1868, Orlando, wife Sarah, and their children moved from post to post throughout the southern USA. Orlando was a Colonel by 1868, when he and the family were sent to Indian territory. In 1873, the family was posted to Louisville, Kentucky. This was the first time that Allen, then 13 years old, was able to attend a regular school. It lasted for only a year, as Colonel Moore was ordered to Fort Buford, Dakota, in May, 1874. After a year on the frontier, mother Sarah Moore’s health began to fail, and she moved with the children to Coldwater, Michigan. Regular schooling was again possible for Allen.

During that time in Coldwater, Allen published his first microscope article. The American Journal of Microscopy published his tips on producing quality slides of “crystals of silver”. He was then 16 years old.

Allen also published requests to exchange microscopical specimens, such as “For Tingis hyalina, send other objects of interest, polycistina especially, to Allen Y. Moore, P.O. Box 68, Coldwater, Mich”, and “For Daphnia pulex, send other unmounted objects - Polycystina especially - to A.Y. Moore, P.O. Box 68, Coldwater, Mich”.

Mrs. Moore moved the family yet again, in June, 1877, to Tulare, California. Mrs. Moore died there in August, 1878.

While in California, Moore published an insight on how he taught himself through reading, “recalling to mind the balsam lenses I have made in times past. Of course these cheap lenses can not be used for scientific purposes, nor their performance be depended on for accurate work, nevertheless they may be made very instructive and entertaining, and with a good book, such as Rev. Wood's ‘Common Objects of the Microscope’, or Lankester's ‘Half Hours with the Microscope’, almost any person can learn enough to pay for the trouble of making the microscope and the money expended for the book. About two years ago - it was before the summer of 1876 - I made and experimented with some of these balsam lenses. I found it difficult to make a lower power than twenty diameters, with good definition, but the higher powers were much more easily made and gave far better results, but they had a very short working distance and were hard to use on that account. I used a pill box with a hole in both bottom and cover. Over the bottom (outside) was a thin piece of mica; on this mica, inside of the box, was a very small drop of balsam. For a diaphragm I used a piece of black tissue paper with a pin hole in it; this was gummed on the outside of the mica - the hole coming under the lens - and the edges turned down around the box, which was then covered with gilt paper. It then presented a very neat appearance. The highest power I ever made, was 300 diameters, and it had working distance enough to use No. 1 covers. I used to take considerable pleasure in ‘fighting’ these balsam microscopes against cheap nonachromatic compound microscopes, such as Queen's and McAllister's ‘Household’ etc. The balsam lenses would usually beat! This morning I came across a box containing four of these balsam microscopes, among them was the one magnifying three hundred diameters. I took a slide of Stauroneis phoenicenteron from my cabinet, and was surprised to see how plainly I could see them. I got a glimpse of the lines but they did not show very plainly until I moved my hand so that sunlight could strike them, when, to my surprise, I saw them clearly and beautifully resolved. These lines number about 34,000 to an inch”.

Allen evidently also spent time in San Diego during that period, as he wrote a letter to The American Journal of Microscopy from that city, dated November 16, 1877. This referred to a slide of a diatomaceous mineral he identified as coorongite, which he had previously sent to a colleague in the east. In his letter, Moore offered to send additional samples. This letter indicated that 17 year-old Moore already had extensive contacts for exchanging material, as he had received the original coorongite sample from “Dr. H.T. Whittell, of Adelaide, South Australia”.

Microscopist Charles M. Vorce, in a memorial to Moore, wrote, “While living in Tulare he began the correspondence and exchange of slides which ultimately made him so well and widely known to many who never personally met him. I have in my cabinet a slide received from him in August, 1877, accompanied by an request for exchange; the mount appearing to have been made in February of that year. The object is the flea of the cat, very well prepared and very neatly mounted between two covers cemented over a central hole in a wooden slip. This was the beginning of a correspondence which was continued at intervals until the Detroit meeting of the (American Society of Microscopists) in 1880, where I was approached by a boyish looking stranger, who called me by name and introduced himself as ‘your boy correspondent, Allen Y. Moore’. I was greatly surprised at his youth, for although he was no mere boy, I had formed from correspondence with him and from his writings in the microscopical journals, the idea that he was a much older person. This was the beginning of a friendship between us which was never interrupted nor marred by a disagreement other than in matters of opinion”.

After his mother died, Moore returned to Coldwater, Michigan, along with his sister, Jessie.

In the fall of 1879, Moore entered the Cleveland (Ohio) Homoeopathic Hospital College. Among his classes, Moore was instructed in microscopy by renowned expert J. Edwards Smith, the chair of Microscopy and Histology. Shortly after Moore graduated as Doctor of Medicine in the spring of 1881, Smith retired, and Moore was appointed in his place. He remained in that Professorship for the remainder of his life.

During his college years, Moore published several authoritative articles on microscopy. Moore adopted the nom-de-plume “Nelly A. Romeo” for one article (the name is an anagram of his real name), on resolution of Pleurosigma angulatum diatom frustules. This article prompted curious letters from readers, including George E. Blackham, who referred to “Miss (or is it Mrs.?) Romeo”. Being a college student, Moore signed his reply “Nelly A. Romeo (not Mrs.)”.

Continuing with Vorce, “After being seated in the chair of Microscopy and Histology at the college, Dr. Moore determined to pursue the work of Microscopical Analysis as a business, instead of entering into general practice. For some time before he graduated he had been engaged in microscopical analysis for physicians in active practice, devoting especial attention to urinary analysis, tumors, etc. In this work he was rapidly gaining prominence, and at the time of his death had already acquired a patronage extending throughout Ohio and into the adjoining states. Personally, I have little doubt that had Dr. Moore been spared a few years longer, and especially had he been less modest and unassuming and possessed more of that faculty which even physicians are occasionally blessed with, known as blowing his own horn, he would have earned a national reputation as an expert in microscopical analysis and diagnosis, especially in histology and pathology”.

“(Moore) had studied the optics of the microscope exhaustively in all aspects, and was in fact a thorough theoretical optician, familiar with all the causes and effects which enter into the result of the use of the best modern objectives, whether they related to the construction of the objective itself, the conditions under which it is used, or the nature and mounting of the object. He studied the correction of objectives not from the side of the effect but from the side of the cause, hence he never moved the adjusting collar without knowing not only exactly why he would move it, but in what direction it should be moved, and what the result would be. The nature and effect of immersion media, and of mounting media, were studied by him in the same manner, and the methods of illumination with equal thoroughness. In this direction were pointed his studies in the silver plating of rulings and diatoms. He also made many experiments in the composition of mounting media of high refractive index, experimenting particularly with various metalloids, he produced independently and at about the same time as Prof. H.L. Smith, the sulphide of arsenic medium of 2.48 index, and had prepared a medium less highly colored which he believed would prove valuable, but the formula for which has not been preserved”.

Moore was the first person to successfully double-stain nucleated blood cells, which he incorporated into his slide-selling business. An 1883 advertisement, “For sale - Mounts of renal tube casts and double-stained blood corpuscles. $1.00 per slide. A.Y. Moore, 53 Prospect St., Cleveland, Ohio”.

As noted above, in Figure 3, Moore was an advocate of vertical illumination devices. These permitted close, high-magnification work on opaque objects, by transmitting light through the objective lens, whereupon it reflected back into the lens and into the viewer’s eyes. Due to the short working distance, it was impossible to examine opaque objects with standard lenses and side-lighting. Moore took advantage of vertical illumination to pursue a distinctive medium in which to mount diatoms, “It is pure silver. By Brewster it is stated that the refractive index of silver is 3.27. One side of the diatom is burned to the cover-glass and the other side is then coated with the silver. The visibility of a diatom so prepared is four times as great as when dry mounted, or more correctly, in the proportion of 1.84 to .43! The results obtained by giving such a visibility to the diatom and at the same time utilizing the full aperture of the objective, can hardly be imagined by one who has never seen it. The dots upon Amphipleura pellucida are shown in a way which would readily convince those who still deny their existence. Even Rhizosolenia alata, yields transverse lines, which, so far as I know, have never been seen by any other method”.

These silvered diatom slides were evidently produced for sale, as a note in The Microscope, 1884, stated, “Dr. A.Y. Moore, is forever doing something to startle his friends. He now produces an elegant slide of silvered Amphipleura pellucida. It is used with a Beck's vertical illuminator and the results are very fine”.

Moore married Gertrude M. Neele on December 30, 1884, in Coldwater. Vorce wrote that Gertrude “evinced a more than wifely interest in his professional work and soon became so expert that she aided him largely in his work, both in analysis and in the preparation of slides. Not a few of the slides sent out by Dr. Moore were the work of her fair hands”.

This lasted for a little more than two years. Vorce wrote, “Although he had inherited a constitution far from robust, which the privations and hardships of his youth had not served to strengthen, Dr. Moore, perhaps on account of his army training, had always an almost utter disregard of any care for his health, and seemed to fear no exposure to either heat, cold or wet. He never seemed to suffer from these exposures, but his apparent recklessness as to his health caused much uneasiness to his friends, who feared to see him a victim to consumption. This was not to be, but an equally fatal, though unlooked for, result was in store. On the 8th day of April, 1887, he was suddenly taken ill, and although he would not at first believe that his illness required the attendance of a physician, it speedily became apparent that he was seriously ailing and medical aid was summoned; but despite all that the best medical skill could do he rapidly sank, and on the 16th day of April he breathed his last, his painful illness having lasted just one week”.

“With all his abilities and acquirements, of which he could not himself be ignorant, Dr. Moore was the personification of modesty. He was so thorough in all matters that he was always sure of the position he took upon any question, and expressed his views clearly and boldly when they were challenged, but he never obtruded his own opinion unsought or officiously, and I do not believe a boastful or conceited expression was ever heard from his lips. His loss is one long to be mourned and his place in the front rank of microscopists will not soon be filled”.

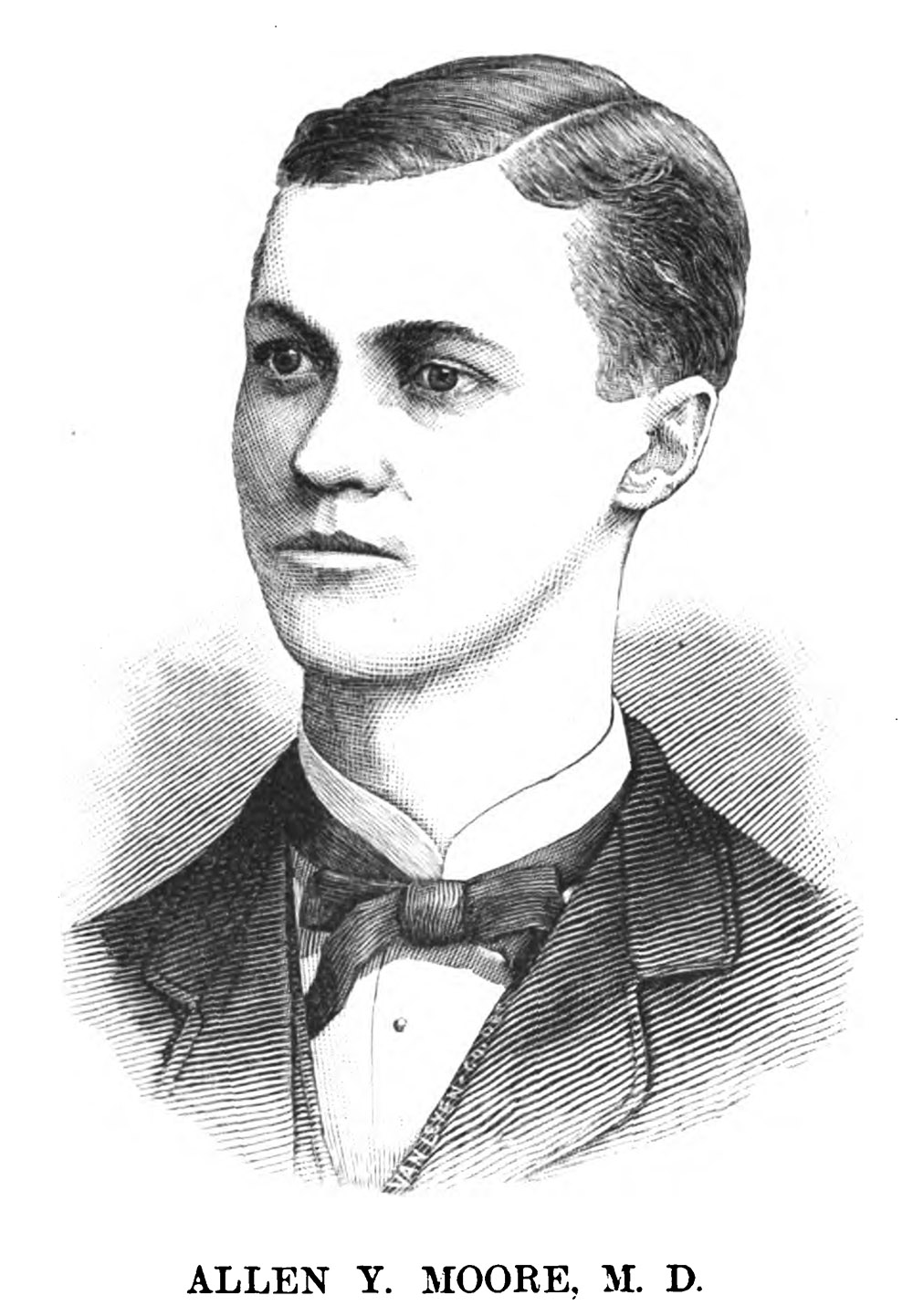

Figure 4.

Drawing of Allen Y. Moore, from his 1887 obituary in "The Microscope". The sketch was likely a copy of a photograph.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Barry Sobel for providing images of a Beck vertical illuminator, http://www.microscope-antiques.com/beckvertill.html, and to Pete Hodds for directing me towards the picture of Allen Moore in The Microscope, 1887.

Resources

The American Journal of Microscopy (1876) Exchange offer from Allen Y. Moore, Vol. 1, page 144

The American Journal of Microscopy (1877) Exchange offers from Allen Y. Moore, Vol. 2, pages 16, 24, 40, and 52

The American Journal of Microscopy (1877) Exchange offer from Allen Y. Moore, Vol. 5, page 224

Blackham, George E. (1880) P. angulatum, , The American Journal of Microscopy, Vol. 5, page 160

The Cleveland Medical Gazette (1887) Resolutions of the Cleveland Microscopical Society in regard to the death of Allen Y. Moore, Vol. 2, page 255

Journal of the Royal Microscopical Society (1885) Diaphragms for Beck’s vertical illuminator, Series 2, Vol. 5, page 522

The Microscope (1883) Advertisement from A.Y. Moore, Vol. 3, page 48

The Microscope (1884) Editorial note on Moore’s silvered diatom slides, Vol. 4, page 165

The Microscope (1884) Exchange offers from A.Y. Moore, Vol. 4, pages 24, 48. 72, 143, 194, 240, and 264

Moore, Allen Y. (1876) Crystals of silver, The American Journal of Microscopy, Vol. 1, page 48

Moore, Allen Y. (1877) Letter on coorongite, The American Journal of Microscopy, Vol. 2, pages 169-170

Moore, Allen Y. (1877) Canada balsam microscopes, The American Journal of Microscopy, Vol. 3, pages 150-151

Moore, Allen Y. (1880) A word on duplex objectives of wide aperture, The American Journal of Microscopy, Vol. 5, page 90

Moore, Allen Y. (1880) Highest magnifying powers, The American Journal of Microscopy, Vol. 5, page 174

Moore, Allen Y. (1881) Shallow tin cells, The American Journal of Microscopy, Vol. 5, pages 79-80

Moore, Allen Y. (1882) The differential staining of nucleated blood corpuscles, Scientific American, Vol. 14, page 5510

Moore, Allen Y. (1883) Markings on Podura scales, Journal of the Royal Microscopical Society, Vol. 3, page 501

Moore, Allen Y. (1883) A new 1-6 inch objective, American Monthly Microscopical Journal, Vol. 4, pages 2-3

Moore, Allen Y. (1883) Amphipleura pellucida by central light, The Microscope, Vol. 3, pages 49-51

Moore, Allen Y. (1884) The parabola as an illuminator for homogenous immersion objectives, The Microscope, Vol. 4, pages 27-30

Moore, Allen Y. (1884) Beck’s vertical illuminator and immersion objectives, The Microscope, Vol. 4, pages 157-159

Moore, Allen Y. (1884) The Fakir’s secret, The Microscope, Vol. 4, pages 169-171

“Romeo, Nelly A” (1880) Pleurosigma angulatum, The American Journal of Microscopy, Vol. 5, pages 137-138

“Romeo, Nelly A” (1880) A reply to Dr. Blackham and “Four Inch”, The American Journal of Microscopy, Vol. 5, page 185

United States Medical Investigator (1881) “Allen Y. Moore M. D., of Coldwater Michigan, has accepted and is now filling the chair of microscopy in the Homoeopathic College, Cleveland, O.”, New series, Vol. 14, page 598

U.S. census, marriage, and other records, accessed through ancestry.com

Vorce, C.M. (1887) Allen Y. Moore, M.D., The Microscope, Vol. 7, pages 137-139

Vorce, C.M. (1888) Memoir of Allen Y. Moore, M.D., Transactions of the American Society of Microscopists, Vol. 9, pages 327-333

http://www.microscope-antiques.com/beckvertill.html