Murray and Heath

Robert Murray, 1798 - 1857

Robert Vernon Heath, 1819 - 1895

Charles Heisch, 1820 - 1892

Robert Charles Murray, 1839 - 1918

by Brian Stevenson

last updated March, 2017

Neither founder of the London optical firm of Murray and Heath was with the business long enough to contribute substantially to the company’s well-regarded microscopes. The partnership was founded in 1855, and Robert Murray died in 1857. Soon afterward, in 1862, Vernon Heath (the “Robert” was rarely used) sold the business to Charles Heisch. Heisch then sold the business in 1869, to the founder’s son, Robert Charles Murray. Robert C. Murray had been an employee of his father and Heath, and managed the business during Heisch’s time, and was evidently the mind behind the firm’s microscopes and other apparatus.

The business retained the name “Murray and Heath” from its inception until 1882. Robert C. Murray then reorganized under his own name, and operated as such until 1890. He then shut the business, and worked as manager for John J. Griffin & Sons for two years. In 1892, Robert C. Murray was re-established as a business (almost next-door to Griffin’s shop), and remained in business until after the turn of the century.

Murray and Heath produced microscopes that primarily targeted medical students and middle-class amateurs. The company is probably best known to microscope enthusiasts for their “Sea-Side” instruments, microscopes that fold into very compact sizes (Figures 1-3). Other types of microscopes and related equipment were also manufactured, or brought in from other makers (Figures 4-9). Additional Murray and Heath apparatus, including some of their cameras, are shown toward the end of this essay.

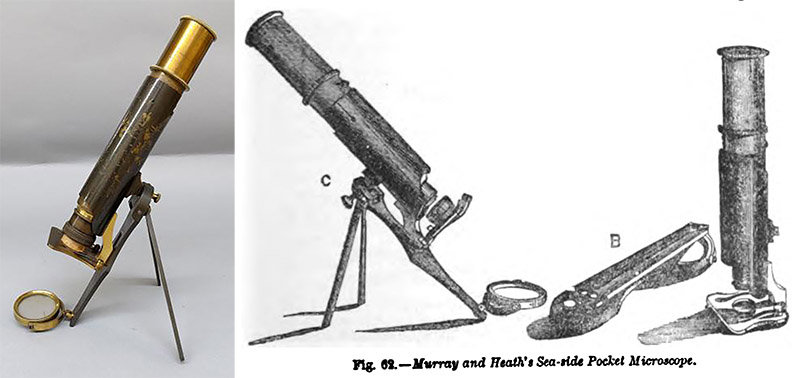

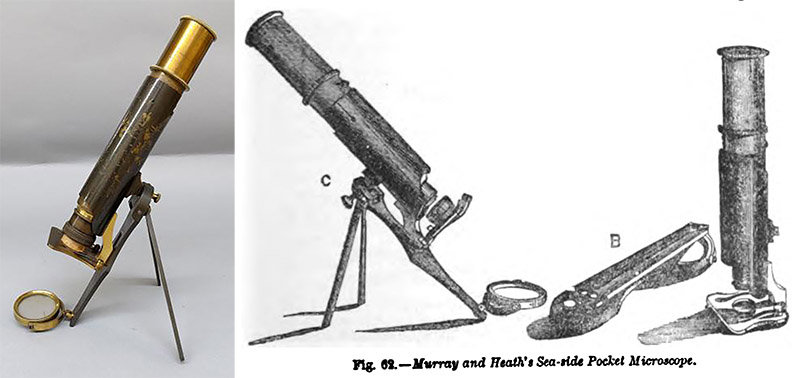

Figure 1.

A circa 1870 “Sea-Side” microscope by Murray and Heath, and images from the 1871 edition of Jabez Hogg’s “The Microscope”. The firm was advertising this microscope in 1866 (see Figure 20, below). The tripod stand unscrews from the body, and folds up. The body can be used without the stand or mirror, as a handheld microscope. Photograph adapted from http://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/sea-side-microscopy-favorite-19th-century-summer-hobby.

Figure 2.

A later version of the “Sea-Side” microscope. The case is labeled with the Jermyn Street address, dating it between 1866 and 1882. The legs unscrew from the body, and everything folds into a box that is less than 6 inches / 15 cm long. A live-box was standard with these instruments.

Figure 3.

A Robert C. Murray “Sea-Side” microscope. He operated under that name from 1882 until 1890, then from 1892 until after the turn of the century. The legs do not unscrew, but instead fold back along the body. Several other copies of this model are known that are signed by Charles Baker, a major London microscope manufacturer, suggesting that Baker was the actual maker.

Figure 4.

A “First-Class” microscope by Murray and Heath, circa 1864. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Figure 5.

Two binocular versions of an 1860s Murray and Heath design. The left-hand microscope was donated to the Royal Microscopical Society by Charles Heisch in 1869. Heisch described the binocular prism apparatus of these microscopes to the Royal Microscopical Society in May, 1868. Both images adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from images from the Museum of History and Science, http://www.mhs.ox.ac.uk/collections/imu-search-page/record-details/?thumbnails=on&irn=16191&TitInventoryNo=10109

and

http://www.mhs.ox.ac.uk/collections/imu-search-page/record-details/?thumbnails=on&irn=5900&TitInventoryNo=39347.

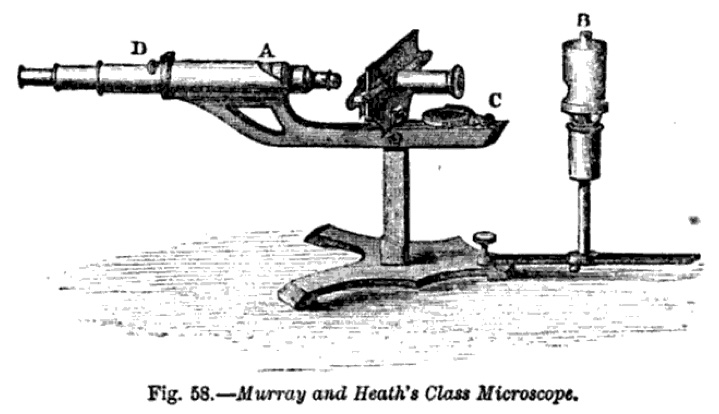

Figure 6.

Circa 1868 set of six simple lenses, loupe, and stand. Produced by Steinheil and Sons, Munich, and retailed by Murray and Heath. The firm moved from 43 Piccadilly to 69 Jermyn Street in1866. Adapted by permission from Allan Wissner’s on-line collection, http://www.antique-microscopes.com/photos/loupe.htm.

Figure 7.

Murray and Heath's “Student’s” microscope, ca. 1871. At left is an illustration of this model from Jabez Hogg’s 1871 edition of “The Microscope”. Hogg remarked that the focus used a chain for movement, and that “the stand is remarkably firm, and, being bronzed over, is well adapted for daily use in the class-room or laboratory … A binocular body, with fine adjustment, is added for a small additional sum, and the instrument then becomes all the student can desire”.

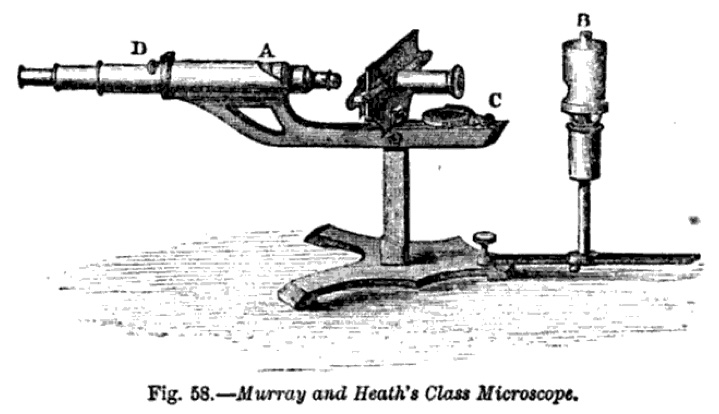

Figure 8.

The “Class” microscope, as illustrated in Jabez Hogg’s 1871 edition of “The Microscope”. It was “especially intended for the use of teachers in the demonstration of objects to a class of students … Messrs. Murray and Heath have constructed an instrument intended to combine an ordinary with a demonstrating or class microscope. It consists of the usual microscope body (A), which can be inclined at any angle, with a mirror (C) on a ball-and-socket joint; and a stage plate with universal movement. When about to be used as a class microscope, the slide is placed in a shallow box into which it is locked by means of a key. The same key locks this box firmly on the stage-plate. When the object has been found, this latter can be secured firmly on the stage in the same manner. After focussing, the body is also locked in its place with the same key, which is seen at D, the final adjustment being made with the eye-piece. The body is then placed in the horizontal position, and fastened with a screw. The instrument can now be passed round a class-room without possibility of injury either to object or object-glass. The illumination is obtained either by directing the instrument towards the window, or by means of a small lamp (B) … This instrument appears to be particularly well adapted to the purposes for which it is intended, and, at the same time, if without the contrivance for locking, to be a useful portable form for general, professional, or sea-side purposes … It should be added, that a novel and efficient form of achromatic condenser is supplied with the instrument; a series of small stops of various sizes are made to drop into a minute hole drilled in the centre of the anterior plano-convex lens, which convert it into a spot-glass, or dark-ground illuminator”.

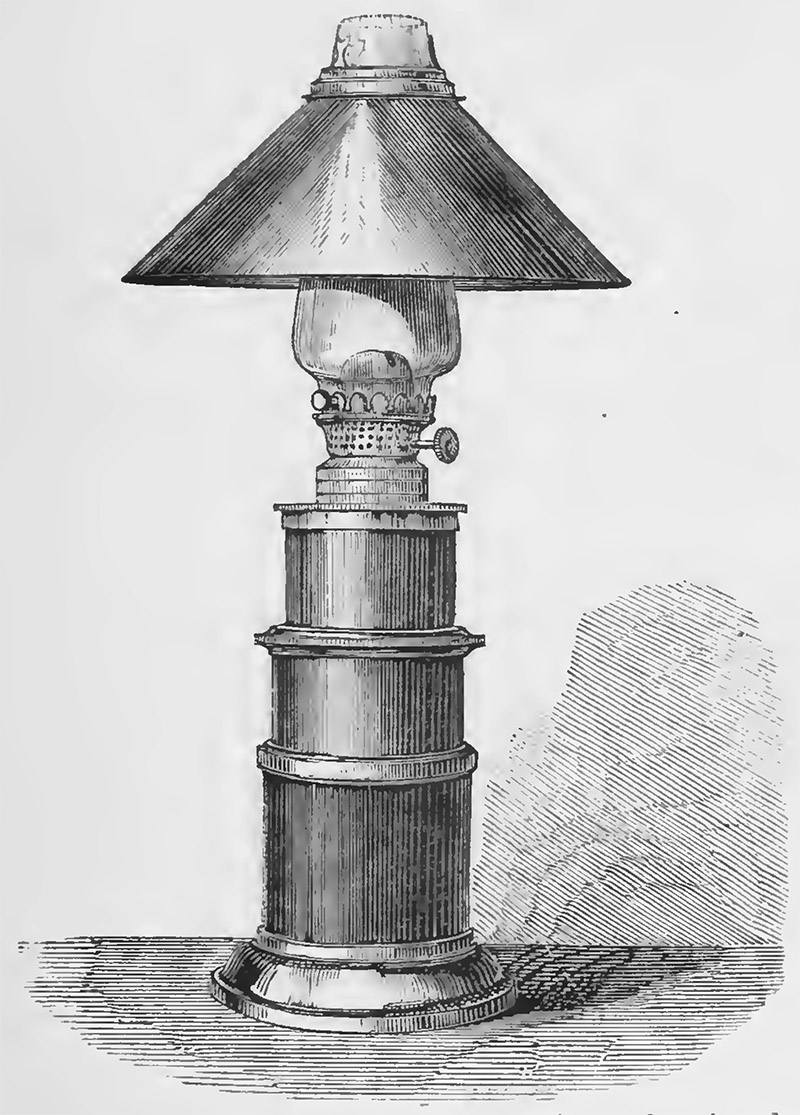

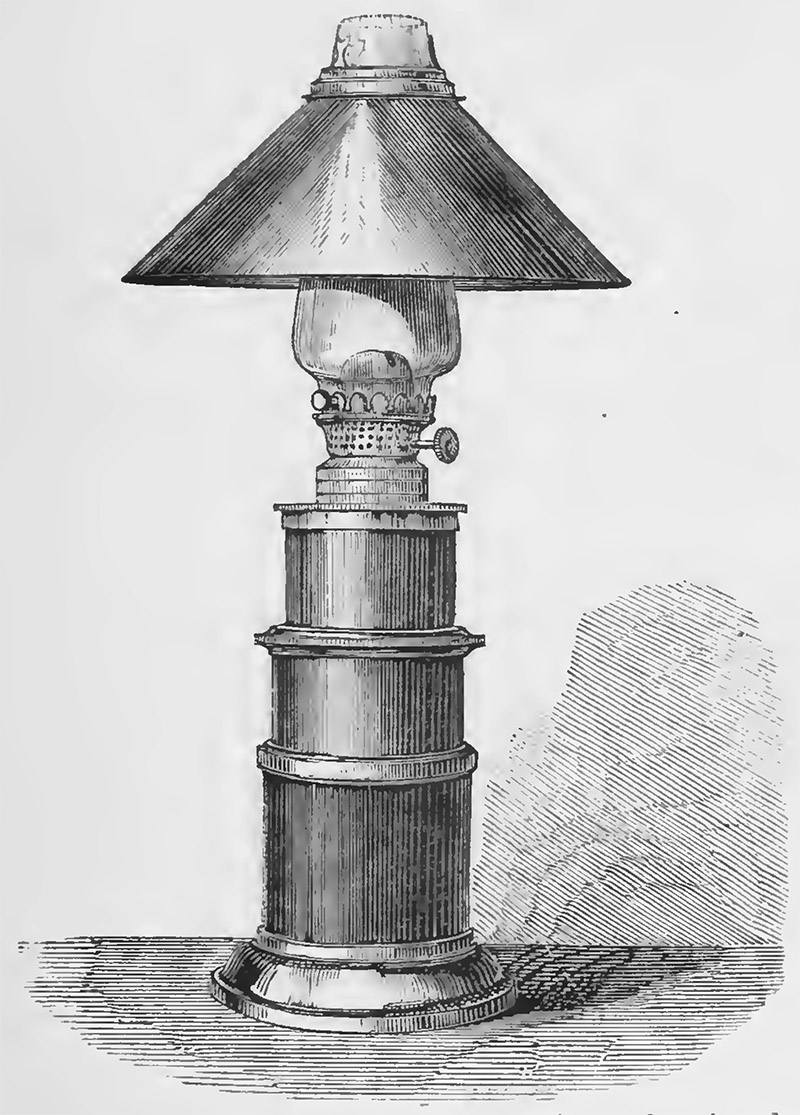

Figure 9.

Murray and Heath’s “Telescope” microscope lamp, as exhibited to the Royal Microscopical Society in 1868. “The lamp consists of three tubes sliding in one another, the oil or paraffin vessel being contained in the inner tube. Spiral guides being cut in each of the tubes, the height of the lamp is regulated to the greatest nicety by simply turning one tube in the other, the guides preventing all chance of slipping. The advantages are compactness, and the absence of the stand and bar usually used for raising and lowering the lamp, which enables the lamp to be used on all sides, and allows of its being brought much closer to the microscope when desired”.

Robert Murray (Figure 10) was born in Athy, Ireland, on September 17, 1798. His father was an officer in the Princess of Wales Light Dragoons, serving in Ireland at that time.

When he was fourteen years old, in 1812, Robert began an apprenticeship in London with scientific instrument-maker John Newman (1783 - 1860). Newman sequentially operated shops on Lisle Street and at 122 Regent Street. Photography pioneer William Henry Fox Talbot (1800 - 1877) began renting space above Newman’s Regent Street shop in early 1847, which was operated as a photographic studio by Nicolas Henneman (1813 - 1898). The following year, Henneman took over the studio, in partnership with Thomas Augustine Malone (1823 - 1883). Those connections put Murray in direct contact with the leaders of early photography. He and his son owned, and evidently sold from their businesses, many early photographs by Talbot and others. Son Robert C. Murray later wrote of a talbotype in his possession that showed his father and himself, dated 1849, and produced by Thomas Malone. He further reminisced of visiting Antoine Claudet’s daguerreotype studio, nearby at 107 Regent Street.

Robert and his wife, Sarah, had at least 8 children, 6 girls and 2 boys. Robert Charles was the eldest boy, and fourth child.

From an 1857 obituary: “For forty-three years he remained in Mr. Newman’s service. During this time he became acquainted with all the scientific men of London. He assisted Sir Humphrey Davy, Professors Faraday, Wheatstone, Daniell, and Brande, in preparing courses of lectures at the Royal Institution and at King's College. For many years, he also assisted in keeping meteorological observations for the Royal Society at Somerset-house. His skill and inventive genius were not limited to helping others only, for in 1841 he received the silver medal of the Society of Arts for the invention of a process for taking Voltatype impressions from non-conducting substances by means of a thin coating of plumbago”.

Our Robert Murray should not be confused with another man of the same name, who made a series of famous photographs of Egypt during the mid-1800s. That Robert Murray was an engineer, lived from 1822 - 1893, and is not known to be related to our Murrays.

Murray and Heath, established in 1855 by Robert Murray and Vernon Heath

Murray left Newman in 1855 to open the shop with Vernon Heath, at 43 Piccadilly. Newman appears to have remained in business until his death, in 1860, as he was awarded a patent for “improvement in spectacles” in 1858.

Robert Vernon Heath (Figure 13) was born during 1819 in Somerset, Bath. In 1841, he moved to London to live with his uncle, Lord Robert Vernon. Lord Robert was a keen supporter of modern artists of the time. Vernon’s memoirs describe that he and his uncle purchased large numbers of paintings, and include numerous anecdotes of artists such as Landseer and Turner. Both men contributed a substantial number of artworks to national museums.

Heath later reminisced, “On the 25th of January, 1839, I went to the Royal Institution to hear a discourse by Dr. Brand. At its close Professor Faraday came to the lecture table, and, to my intense gratification and surprise, announced the two discoveries—the Daguerreotype and Mr. Fox Talbot's invention, then called ‘photogenic drawing’. Mr. Faraday invited his audience to inspect the specimens displayed in the library of the Institution, and I, being one of those who did so, saw realised that which my camera lucida had so often led me to speculate upon, and from that moment I was, in heart and spirit, a disciple of the new science – photography ... By 1841 Mr. Fox Talbot had made important advances in his photographic researches, and had brought out his calotype process ; this I followed with keen interest. I bought my first camera and lens of Andrew Ross, in 1842, one of the earliest he had made for calotype work ... In the short period between 1850 and the end of 1854, photography had made great progress. Archer's collodion process had been introduced, a process which had shortened the exposure in the camera as 30 is to 480. The optician and camera-maker had, too, immensely improved all photographic appliances. Thus, for all purposes and applications, photography had become practical and could be relied upon. So I became a professional photographer, and taking my camera to well-known scenes and places - my knowledge of drawing and art standing me in good stead - I worked until I felt that, with credit to myself, I might accept engagements at country houses. At that time I also gave instruction and lessons to amateurs, and amongst the many who came to me were Dr. Livingstone - one of my earliest pupils - and Prince Alfred, now the Duke of Edinburgh”.

Vernon Heath married Harriet Hook on February 14, 1844. They had one child, Edith, born in 1847. The 1851 and 1861 censuses record that Vernon, Harriet, and Edith lived in a nice home in Putney, Surrey, tended by three domestic servants.

Heath was undoubtedly the money behind the Murray and Heath partnership. As noted above, he had ample funds to buy artworks at that time. The 1851 census listed his occupation as “joint stock and railway share holder”. Murray had the skills of lens-grinding and camera-making. Both men would have brought practical knowledge of the mechanics and chemistry of photography.

Robert’s son was a part of Murray and Heath from early on. On December 15, 1856, Murray wrote to Michael Faraday, “I am about asking a favour & I hope you will not think I am taking too great a liberty. I wanted my son who is in business with us to hear your lectures. The favour I want to ask is if you could kindly give me an admission for him to go in the gallery. I shall esteem it a great favour hoping you are quite well & will pardon my troubling you”.

Murray and Heath, solely owned in 1857 by Vernon Heath

Robert Murray died in early 1857, leaving Vernon Heath in control of the business. The 1861 census shows that he employed 8 men, one of whom was Robert Charles Murray. The census also records that the partner’s widow, 58 year-old Sarah Murray, had taken work as an “agent for paraffin oil”.

In 1857, the firm supplied optical apparatus to Queen Victoria and Prince Albert (Figure 15), a Royal Appointment that lasted into the twentieth century. They also supplied the Board of Trade, the Foreign Office, the Admiralty, and the East India Company. The firm’s reputation for reliability led to them supplying cameras for Lord Elgin’s 1857 trip to China, and David Livingstone’s 1858 expedition to the Zambezi.

A booklet, Photographic Apparatus, Processes, &c. &c., partly information for photographers and partly an advertisement for the firm, was printed by Murray and Heath in 1859. A full-length catalogue of their goods was also issued that year.

Heath’s contacts and reputation as an excellent, artistic photographer led to a plum contract in 1861: photographing Prince Albert (Figure 16). On July 11, 1861, he was visited by the Prince, and Heath took four negatives. One was for The Statistical Society, one was for the Prince’s own use, one was for Heath to publish as he saw fit, and the fourth was to be sold to Robert Mason, a publisher of Paternoster Row. Heath requested five Guineas from Mason, who then insisted that he was supposed to have two negatives, not one. A lawsuit ensued. Prince Albert died that December, which raised an enormous demand for memorabilia such as photographs of the Prince. Due to the lawsuit, Heath was prevented from selling prints from his negative. Although the case was finally heard a week or two after the Prince’s funeral, and was found in Heath’s favor, it was immediately appealed by Mason. It was not until May that the second trial took place, the result again in Heath’s favor. By then, the excitement for Prince Albert memorabilia had subsided, and the opportunity for a substantial profit had passed. In addition, Heath had legal fees to pay.

Possibly in consequence of his financial losses from the Prince Albert photograph fiasco, Vernon Heath sold the Murray and Heath business in 1862, to Charles Heisch.

Heath remained at 43 Piccadilly, operating a business as a photographer. He was invited to photograph the 1863 wedding of the Prince of Wales, along with many other honors. But, he ran into serious financial trouble in 1865, and declared bankruptcy of both his business and his home in Surrey. This may have been a reason for his evident split with wife Harriet. Until the end of Vernon’s life, he lived in London, while Harriet and their daughter lived with her parents in Buckinghamshire.

Heisch moved the Murray and Heath business away from 43 Piccadilly in 1866. Those premises were then taken by Day & Son, Ltd., who “commenced business as artistic and portrait photographers … under the able management of Mr. Vernon Heath”. The 1871 and 1881 censuses both listed Heath’s home address as being 43 Piccadilly. At some point, Heath acquired ownership of the studio. He again declared bankruptcy, in 1885. His associate and house-mate, Eliza Rosina Swindon, acquired the business, but filed for bankruptcy protection in 1887.

Vernon Heath made a major impact on London, on England, and probably the whole world in 1879. That year saw publication of a small book called Burnham Beeches, which included engravings from photographs by Vernon Heath. The book was a plea to preserve a section of London woodland from development into buildings. Although the woods had been harvested for many centuries, they were as close to native forest as possible. From the preface, “a book was wanted, for the reason that its subject … was terra incognita to vast numbers of people. To such, few things I venture to think, can be more welcome in this age of grinding hard work and bustle and worry, than indications of places where they can bury themselves in delicious greenery with little trouble and at trifling expense—especially when such places are so near the scenes of their daily toil, that the rapid transportation from hot and dusty streets to the coolness, solitude, and beauty of woodland shades, feels almost like enchantment”.

Heath published his Recollections in 1892. The preface was written in June, 1891, addressed from the Brunswick Hotel, Jermyn Street, London. Coincidentally, the Murray and Heath business had moved to Jermyn Street in 1866. Notably absent from Heath’s Recollections is any mention of his association with Robert Murray.

Vernon Heath died on October 25, 1895.

Murray and Heath, purchased in 1862 by Charles Heisch (Figure 19).

An overview of Charles Heisch’s life was provided by the Chemical Society upon his death in 1892: “By the death of Charles Heisch the Society loses another of its original members. Charles Heisch was born at Blackheath on August 2, 1820, and was the youngest son of Frederic Heisch, of Cox, Heisch, and Co., America Square, London.

In consequence of his early liking for scientific experiments, &c., he became, about the age of 15, a pupil of Richard Phillips, F.R.S., in his laboratory at St. Thomas's Hospital, and continued his studies with that chemist at the laboratory in Craig's Court, Charing Cross, then attached to the Geological Survey, which afterwards developed into the Royal School of Mines.

In 1842, Heisch was appointed Assistant Lecturer on Chemistry at St. Thomas's Hospital with Dr. Leeson; in 1848 he was elected joint Lecturer in Chemistry (with Mr. Thomas Taylor) at the Middlesex Hospital, and on the subsequent retirement of Mr. Taylor he became sole Lecturer in the subject until he resigned the chair in 1875. On March 11, 1869, he was elected Superintending Gas Examiner to the Corporation of the City of London, a post which he retained till his death, after a short illness, at Brighton, on January 2, 1892.

Heisch was present at the meeting on March 30, 1841, when it was determined to found the Chemical Society; he was also present at the Jubilee Dinner of the Society on February 25, 1891. He read a paper before this Society, ‘On the Quantitative Estimation of Cyanogen in Analysis’, in 1849, and a second paper, ‘On the Organic Matter in Water’, 1870, which contained an account of his well-known "sugar test." Among his other papers may be mentioned the following: ‘On the Method of Testing the Illuminating Power of Gas, with special reference to Burners’, read before the British Association of Gas Managers in 1870, and an important joint report to the Gas Institute by F.W. Hartley and C. Heisch, ‘On a Consistent Method of Estimating the Illuminating Power of Gas of Different Qualities’, which provoked at the time much discussion. He also had a considerable share in starting the Society of Public Analysts, and was elected, at its foundation in 1874, joint Secretary with Mr. Wigner, a post which he filled until he was elected President in 1881 and 1882. He contributed many short papers to the Analyst on the melting point of fats, and on cocoa, milk, pepper, &c. He was Public Analyst to the district of Lewisham, St. John's, Hampstead, and the borough of Hertford.

Heisch was an accomplished musician, and at one portion of his life devoted much time to photography. He married in 1869, and leaves a widow, but no family. Those Fellows who had the pleasure of his acquaintance will long remember his fine presence, his courteous manner, and his characteristic laugh”.

Heisch's interest in photography predated his acquisition of the Murray and Heath business. In 1852, he edited a book on photography, Plain Directions for Obtaining Photographic Pictures. Around the time he purchased Murray and Heath, Heisch wrote another book, The Elements of Photography (1863). A review stated, “It is almost a matter of supererogation on our part to recommend this little work to the notice of our photographic readers, Mr. Heisch's name being so well known to them both as a clever scientific chemist and as an accomplished practical photographer … Mr. Heisch's remarks on the iodising and bromising of collodion will be found most useful even to the veteran collodion photographer. The author's researches into the action of the mixed iodides and bromides are well known”.

Murray and Heath began a strong emphasis on microscope production under Heisch, with a catalogue of microscopes being issued in 1862 (Figure 20).

The business moved from Piccadilly to 69 Jermyn Street in 1866 (Figure 21). As noted above, the vacancy at 43 Piccadilly was taken by Day & Son’s photographic shop, managed by Vernon Heath.

Heisch became a Fellow of the Royal Microscopical Society during his tenure at Murray and Heath. He also joined the Quekett Microscopical Club, in January, 1867. His manager, Robert C. Murray, joined on that same evening.

The May, 1869, issue of Chemical News included this note: “We understand that Mr. Heisch has relinquished the proprietorship of the business at 69, Jermyn Street, carried on under the name of Murray and Heath. He is succeeded by Mr. Robert Murray, whose father established the business, and as he has for many years acted as manager for Mr. Heisch, he will, we believe, fully maintain the just reputation this firm has acquired”.

The same page of that magazine carried an additional piece of news: “Mr. Charles Heisch, F.C.S., was on Thursday last elected to the office of Gas-Examiner to the City or London. This gentleman is known from his connection with the firm of Murray and Heath”. That responsibilities of that new position may have interfered with Heisch’s ability to run the optical shop.

Murray and Heath, acquired in 1869 by Robert Charles Murray.

Robert C. Murray was born on April 5, 1839. He was christened late in life, on February 16, 1868. He then gave his birth year as 1840, but he was undoubtedly mistaken. The 1841 census listed him as being 2 years old, possible only if he was born in 1839. All other censuses concur with that birth year.

As noted above, a letter from his father to Michael Faraday indicted that young Robert was working for Murray and Heath in 1856. The 1861 census listed him as being a “Philosophical Inst Maker”, evidently with his father’s former business.

Considering that Heisch was a chemist and photographer, and the continued success and novelty of Murray and Heath microscopes after 1869, it is reasonable to conclude that Robert C. Murray was the brains behind those microscopes.

Robert married Jessica Spicer at St James Clerkenwell on August 29, 1863. They had two daughters, Jessica and Emma, born in 1864 and 1867, respectively. A son, John, was born many years later, in 1884. Both daughters later worked as professional photographers.

The 1871 census reports that the Murray family did not live at the Jermyn Street shop, but instead lived in a house in Islington. They employed a 14 year-old girl as a domestic servant and nursemaid. Business was evidently quite good, allowing the Murrays to live a respectable middle-class lifestyle.

In July, 1879, Murray purchased a second location, closer to home, at 113 Pentonville Road, Islington. That shop was named the North London Photographical and Optical Company.

The Murrays, and a servant, lived at 113 Pentonville Road in 1881, suggesting that it was a reasonably-sized home with a shop-front.

Reorganized as Robert C. Murray, 1882

Murray applied for bankruptcy protection of both business locations in 1882. This may have been a financial trick to ditch the Jermyn Street shop, and dodge some creditors. He reopened the 113 Pentonville Road shop as “Robert C. Murray”, and remained in business there until 1890.

1890-1891, closed for business

During early 1890, Murray closed his shop and took employment as manager of the photographic department of John J. Griffin and Sons, at 22 Garrick Street (Figures 24 and 25). This arrangement lasted until the end of 1891.

The Murray family remained in their house at 113 Pentonville Road during that time.

1892, Robert C. Murray is reopened

The January 28, 1892 issue of Photography announced, “Mr. Robert C. Murray has started in business for himself at 8, Garrick Street, Covent Garden, London, W.C., his engagement with Messrs. Griffin & Sons having expired with the end of the year”. The May 26, 1892 issue noted, “Messrs. J.J. Griffin & Sons, 22, Garrick Street, Covent Garden, London, send us a new catalogue of apparatus, in which, amongst other things, we notice the new “Climax” dry plate listed, together with the ‘Rex’ photographic set and other articles, at cheap rates … Robert C. Murray, 8, Garrick Street, Covent Garden, London, sends us a 12-page price list of the ‘King’, ‘Baron’, ‘Queen’, ‘Duke’, and other photographic outfits bearing similar titles”.

Murray opening a competing shop almost next door to Griffin suggests that he did not have especially kind feeling for his former employers. Note also that Murray chose noble titles for his cameras, as did Griffin.

That year, Robert C. Murray regained the honor of being Scientific, Chemical, and Physical Apparatus Manufacturer to Queen Victoria. He retained that title until 1911, his omission from the 1912 list being noted in the British Journal of Photography.

Murray’s shop remained at 8 Garrick Street until some time after 1900. By 1910, he was located at 13 Garrick Street. A December, 1912, letter to the British Journal of Photography gives that same address. The 1911 census recorded that he was still a photographic dealer, working on his own account. He was then working “partly at home”, implying that he still maintained an external shop.

The 1912 British Journal of Photography article further noted, “His business of later years having lain largely in the photographic equipment of expeditions, outfits for explorers, etc., as well as in the manufacture and supply of photographic requisites specially to individual requirements”. This suggests that the majority of apparatus labeled “Robert C. Murray” was probably produced between the years 1882 and 1890, or between 1892 and the very early 1900s.

Robert Charles Murray died on October 29, 1918.

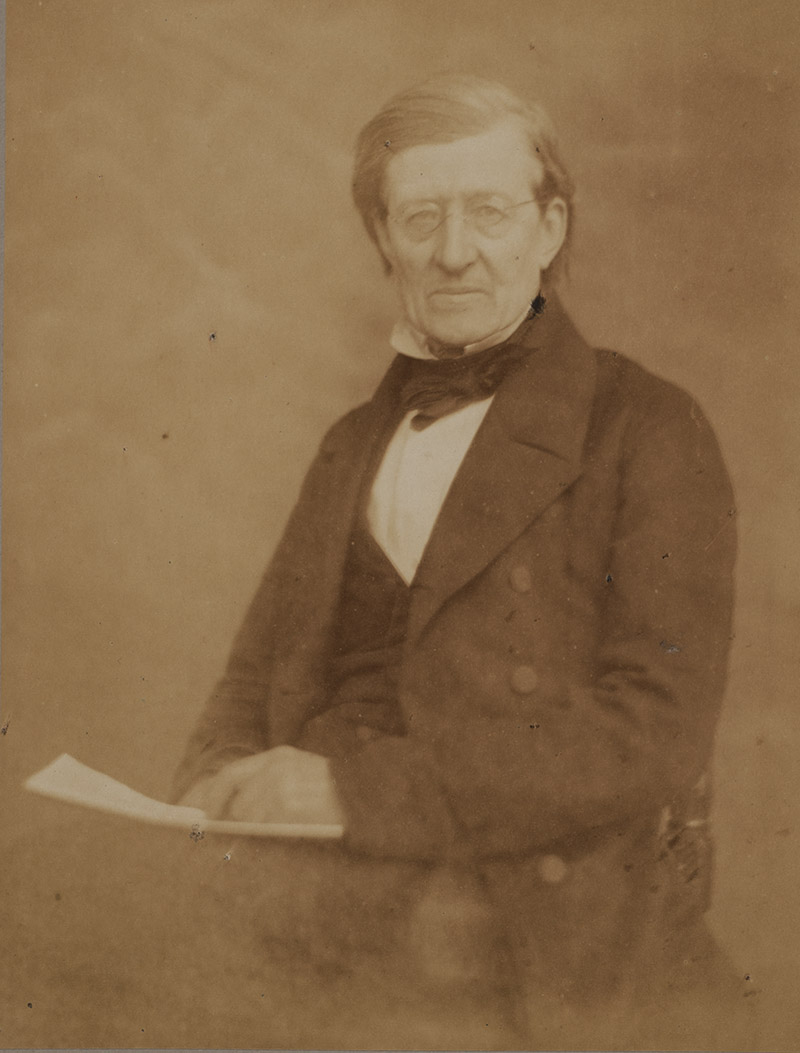

Figure 10.

Photograph of Robert Murray, taken by Robert Crookes and John Spiller, circa 1851. Courtesy of the Gersheim Collection of the University of Texas.

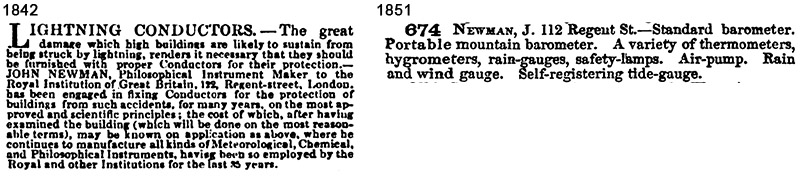

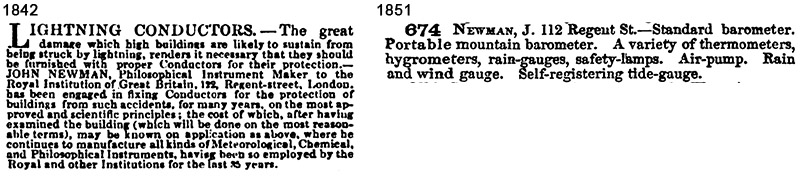

Figure 11.

Announcements of items that would have been made by Robert Murray when working for John Newman: an 1842 advertisement from The Athenaeum, and Newman’s listing from the catalogue of the 1851 London Exposition.

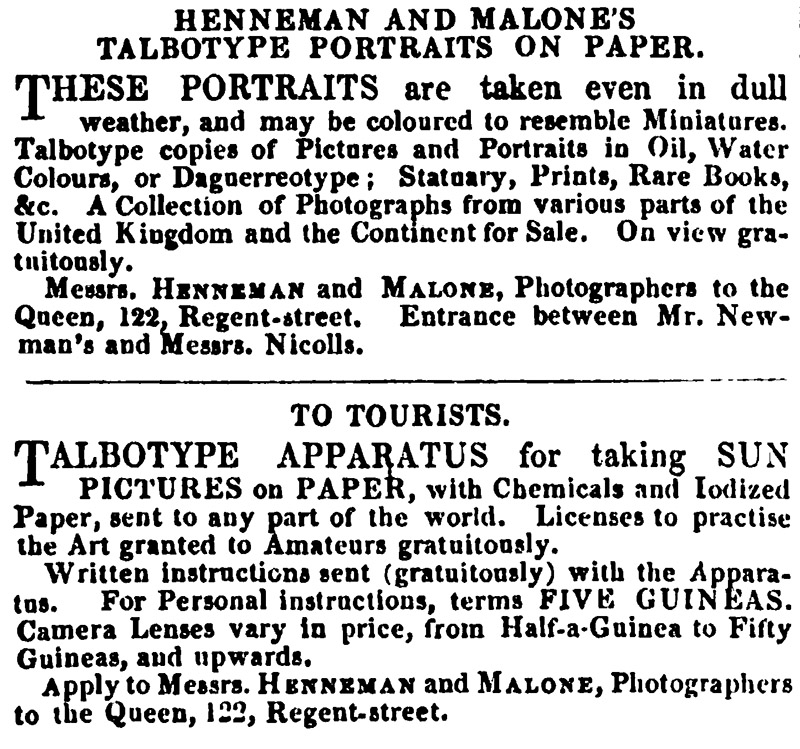

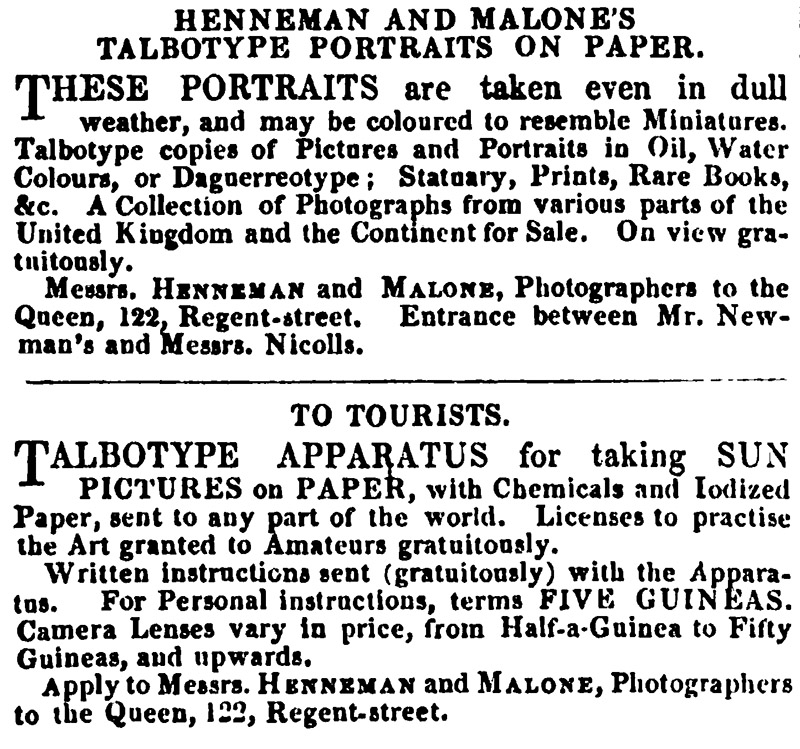

Figure 12.

A pair of 1850 advertisements from photographers N. Henneman and T.A. Malone, who operated a photography studio above John Newman (and Robert Murray). In 1847, W.H. Fox Talbot set up the studio, managed by Henneman. Henneman and Malone acquired the business in 1848.

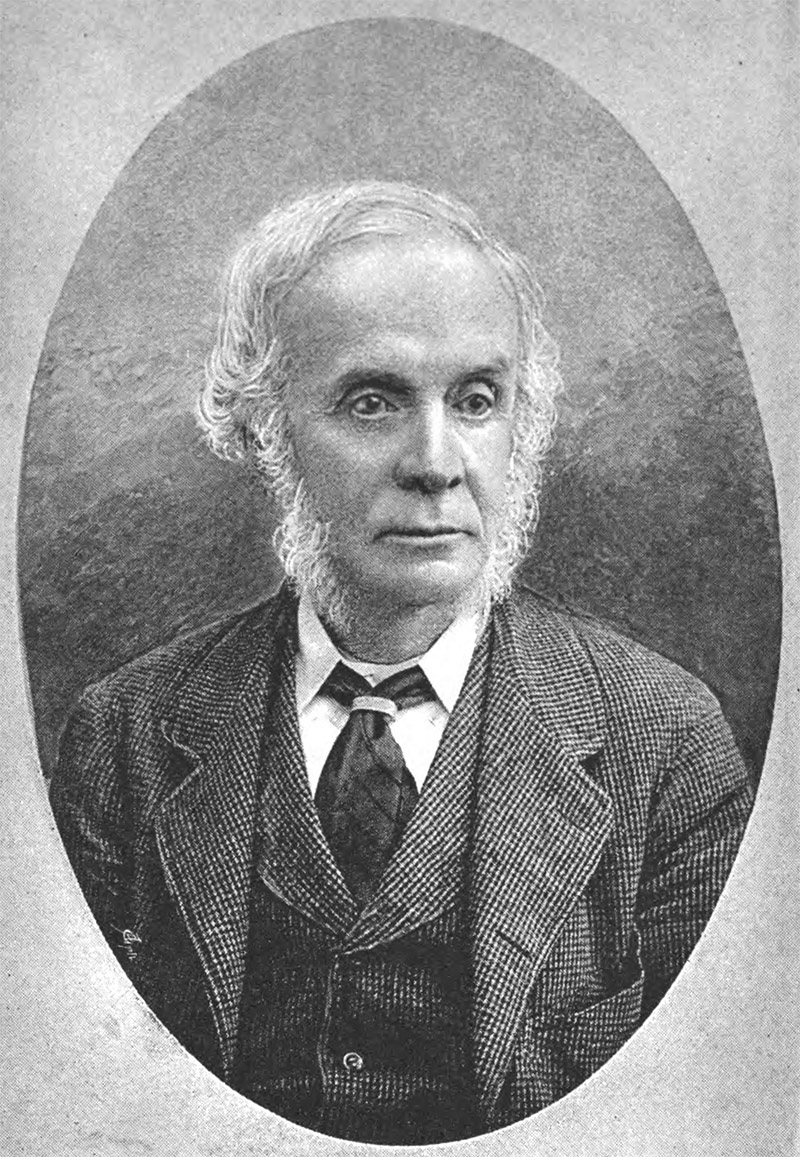

Figure 13.

Vernon Heath, from his 1892 ‘Recollections’.

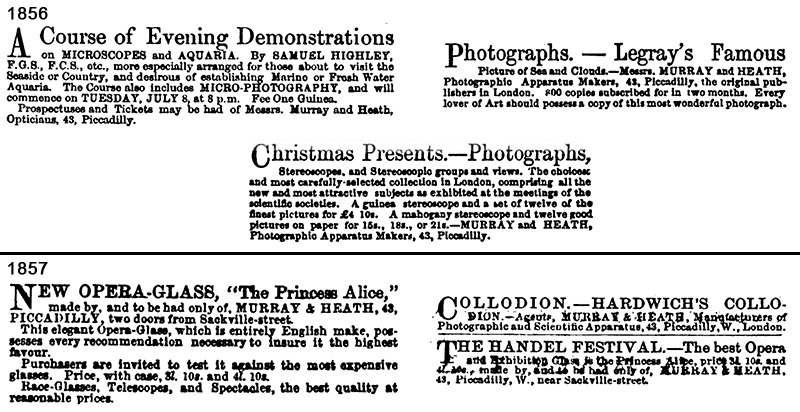

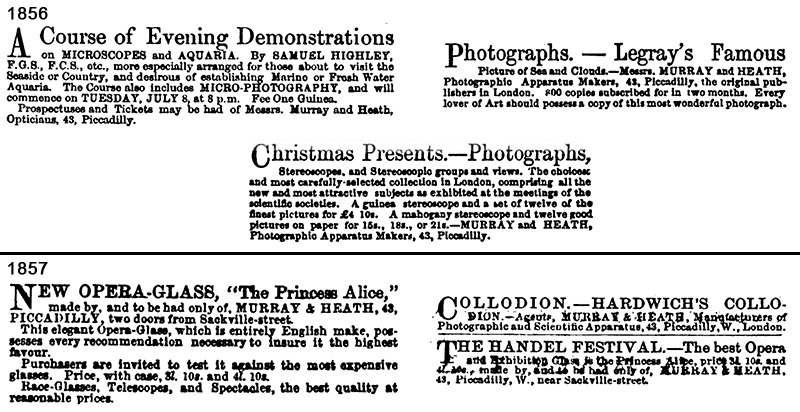

Figure 14.

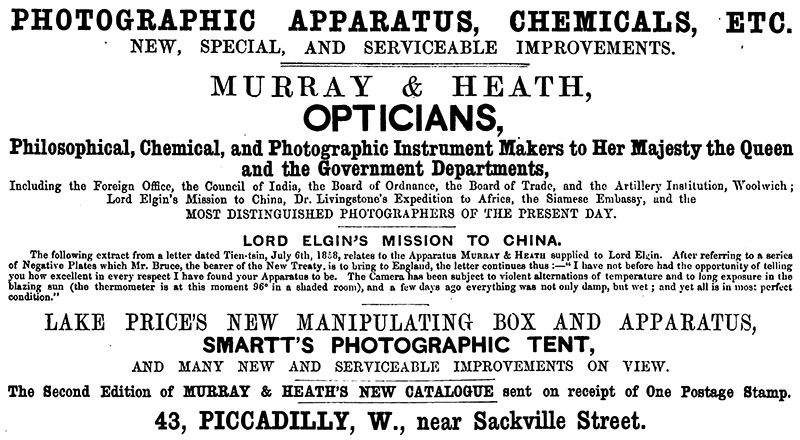

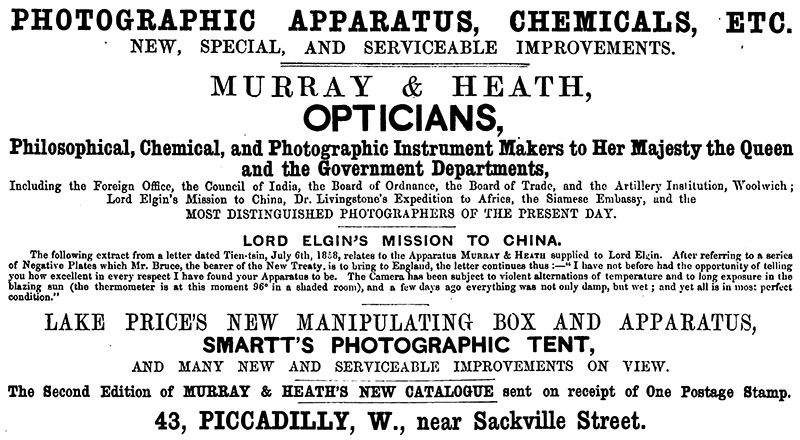

Advertisements from the early days of Murray and Heath.

Figure 15.

Advertisement from the February, 1859, issue of ‘The Art Journal’.

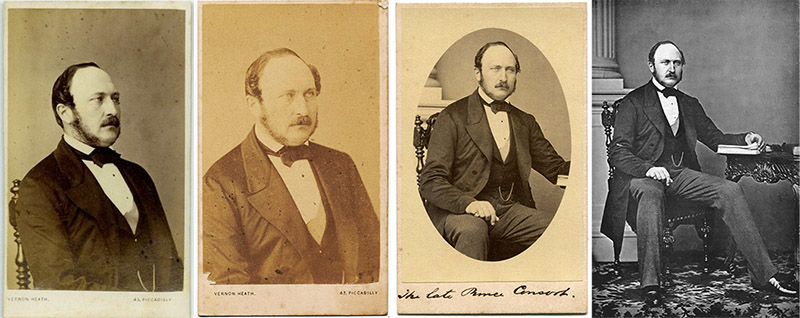

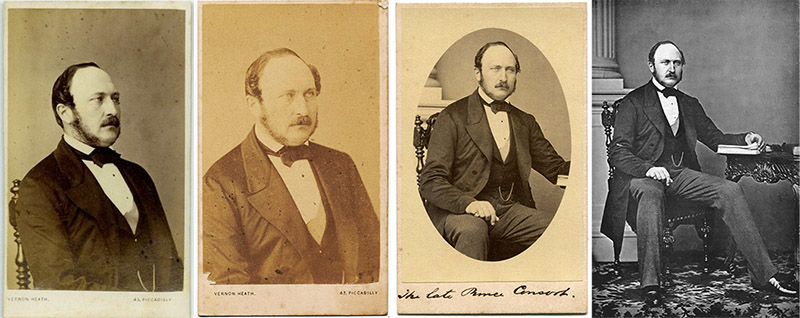

Figure 16.

Photographs of Prince Albert, taken on July 11, 1861, by Vernon Heath. The left two carte-de-visites were published by Heath. Presumably, one of these is the image provided for him in the contract. The third CDV was published by Samuel Poulton (1819-1898), of 352 Strand. At the right is a full view of that image.

Figure 17.

Two carte-de-visite photographs by Vernon Heath, from 43 Piccadilly. Both have the same printing on the reverse. The crown and “Royal Photographic Studio” refer to his contracts with the Royal family.

Figure 18.

An 1871 photograph by Vernon Heath, “Great Scots Fir on Lawn”.

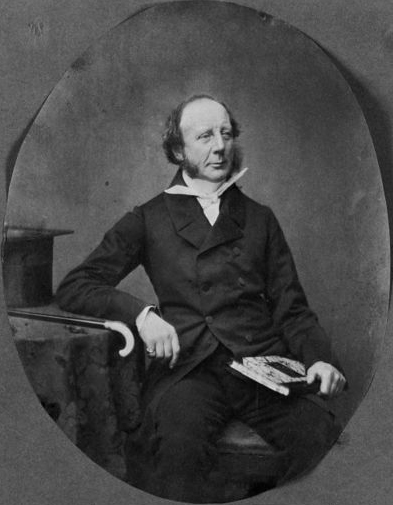

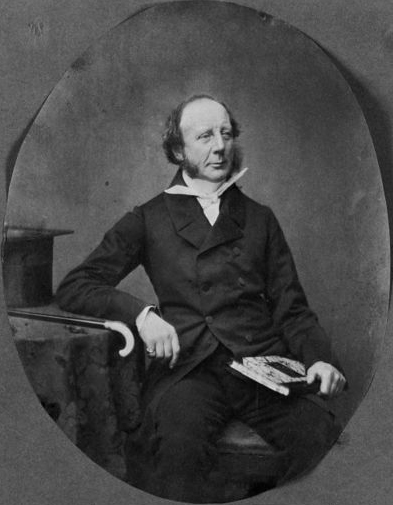

Figure 19.

Photograph of Charles Heisch, adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O133128/photograph-of-dr-charles-heisch-photograph-horne--thornthwaite/

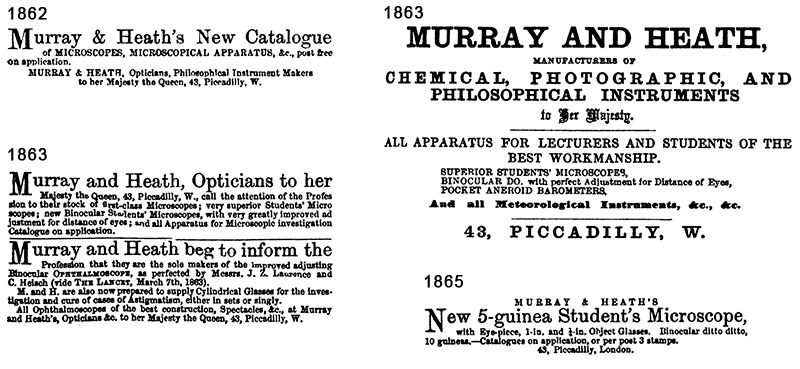

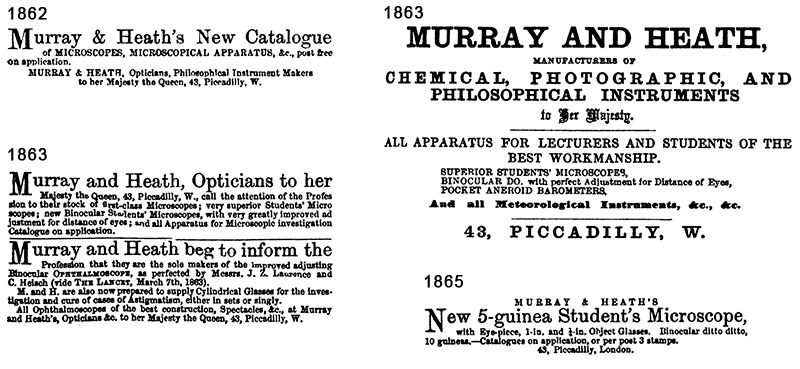

Figure 20.

Murray and Heath began heavily advertising microscopes after the business was acquired by Charles Heisch, in 1862. A catalogue of microscopes was issued that year. At least three forms were produced: a first-class, a student’s binocular, and a student’s monocular.

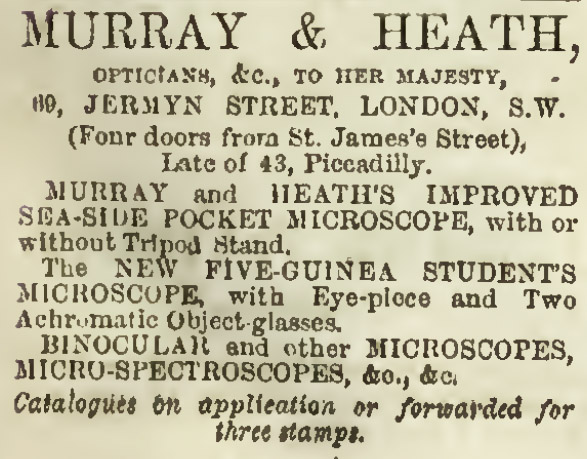

Figure 21.

An 1866 advertisement, following the move from Piccadilly to 69 Jermyn Street. The folding Sea-Side microscope (see Figure 1) was in production by this time.

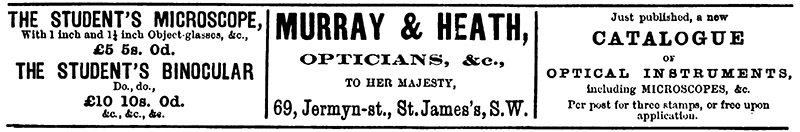

Figure 22.

An advertisement from January 4, 1868.

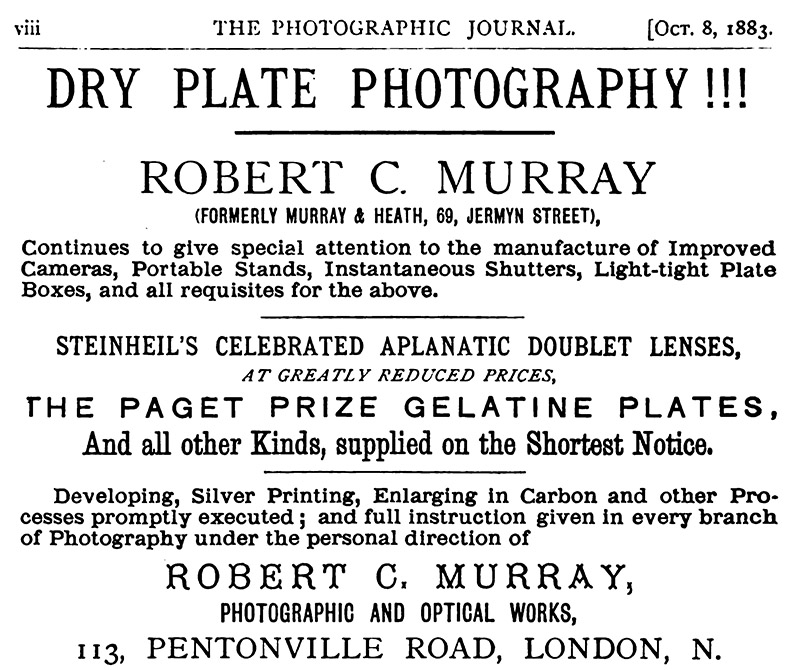

Figure 23.

An 1883 advertisement for Robert C. Murray, 113 Pentonville Road. Murray reorganized his business in 1882.

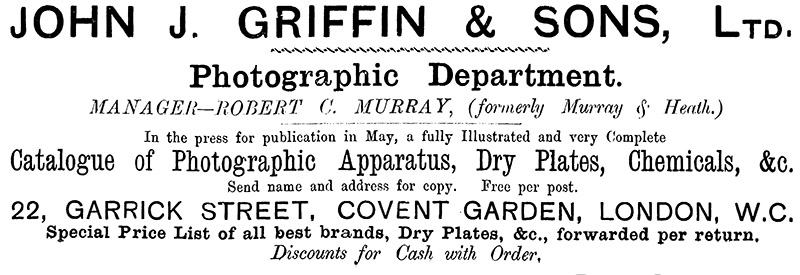

Figure 24.

May 9, 1890 advertisement from John J. Griffin & Sons Photographic Department, managed by Robert C. Murray. These advertisements began on that date, suggesting that Murray closed his own shop a short time before this.

Figure 25.

Two 1891 advertisements from John J. Griffin & Sons.

Figure 26.

Two cameras by Murray and Heath. The left-hand camera, with two lenses, is designed to take stereophotographs. Both are labeled with the 69 Jermyn Street address, dating them to between 1866 and 1882. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from internet auction sites.

Figure 27.

A Murray and Heath barometer. It is labeled with the 69 Jermyn Street address, dating its manufacture to between 1866 and 1882. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from internet auction sites.

Resources

Anthony's Photographic Bulletin (1887) Obituary of Charles Heisch, Volume 18, page 170

Arnold, Harry J.P. (1977) William Henry Fox Talbot: Pioneer of Photography and Man of Science, Hutchinson Benham

The Art Journal (1857) Photographic apparatus &c., New Series, Vol. 5, page 24

The Art Journal (1859) Advertisement from Murray and Heath, Vol. 8, February advertiser

The Athenaeum (1842) Advertisement from John Newman, July issue, front page

The Athenaeum (1857) Advertisements from Murray and Heath, Vol. 30, pages 642 and 769

The British Journal of Photography (1912) Vol. 59, pages 53 and 966

Brock, William H. (2008) William Crookes (1832-1919) and the Commercialization of Science, Ashgate, Aldershot, UK, pages 12 and 26

The Bookseller (1866) Trade and literary gossip, January 31

Chemical News (1863) Advertisement from Murray and Heath, Vol. 8, July 4 advertiser

Chemical News (1863) Review of Charles Heisch’s Elements of Photography, Vol. 8, page 83

Chemical News (1866) Advertisement from Murray and Heath, Vol. 14, July 6 advertiser

Chemical News (1867) Advertisement from Murray and Heath, Vol. 15, April 12 advertiser

Chemical News (1869) Scientific instruments, Vol. 19, page 263

The Engineer (1868) Patent awarded: “William Harding Warner, Ross, Hereford, and Robert Charles Murray, Jermyn-street, London, ‘Improvements in stereoscopes’,” Vol. 25, page 252

England birth, marriage, death, and census records, accessed through ancestery.com

Hannavy, John (2013) Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography, Routledge

Heath, Francis G. (1879) Burnham Beeches, Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, & Livingston, London

Heath, Vernon (1892) Recollections, Cassell and Co., London

Heisch, Charles, editor (1852) Plain Directions for Obtaining Photographic Pictures, T. Willats, London

Heisch, Charles (1863) The Elements of Photography, Murray and Heath, London

Heisch, Charles (1868) On the improvement of Nachet’s stereo-pseudoscopic binocular microscope, Transactions of the Royal Microscopical Society, Vol. 16, pages 111-113

Hogg, Jabez (1871) The Microscope, Eighth edition, G. Routledge & Sons, London, page 103

J. Paul Getty Museum Open Content (accessed August, 2016) free access and downloads of artworks, including photographs by Vernon Heath, http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/artists/6377/vernon-heath-british-1819-1895-active-london-england/

James, Frank A.J.L. (2008) The Correspondence of Michael Faraday: 1855-1860, Institution of Engineering and Technology, London, page 175

Journal for Amateur Photographers (1889) “The photographs of the interior of Temple Church, both small views and enlargements, can be procured of Mr. R.C. Murray, 113, Pentonville Road, N.”, Vol. 33, page 400

Journal of the Chemical Society (1857) Obituary of Robert Murray, Vol. 10, page 191

Journal of the Chemical Society (1892) Obituary of Charles Heisch, Vol. 61, pages 489-490

Journal of the Society of Arts (1856) Advertisements from Murray and Heath, Vol. 5, November 28 and December 12 advertisers

Journal of the Society of Chemical Industry (1892) Obituary of Charles Heisch, Vol. 11, page 146

Journal of the Quekett Microscopical Club (1869) Members, Vol. 1

The Lancet (1856) Advertisement from Murray and Heath, Vol. 2, September 27 advertiser

The Lancet (1863) Advertisements from Murray and Heath, Vol. 2, September 19 advertiser

The Lancet (1865) Advertisement from Murray and Heath, Vol. 2, September 30 advertiser

Leaper, Clement J. (1891) Materia Photographica, Iliffe, London, advertisement from J.J. Griffin and Sons in back of the book

Literary Gazette and Journal of the Belles Letres (1850) Advertisements from Henneman and Malone, June 15 issue, page 414

London Gazette (1865) Bankruptcy of Robert Vernon Heath, p 538

London Gazette (1882) Bankruptcy of Robert Charles Murray, December 8

London Gazette (1887) Bankruptcy of Eliza Rosina Swindon, August 5

Medical Times and Gazette (1856) Advertisement from Murray and Heath, Vol. 34, July 5 advertiser

Medical Times and Gazette (1868) Advertisement from Murray and Heath, Vol. 1, January 4 advertiser

Murray, Robert C. (1910) The credit of discoveries, The British Journal of Photography, Vol. 57, pages 90-91

Official Catalogue of the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations 1851 (1851) entry 674 (John Newman), Royal Commission, London, page 71

PhotoLondon (accessed September, 2016) Murray, Robert Charles, http://www.photolondon.org.uk/pages/details.asp?pid=5547

The Photographic News (1859) Advertisement from Murray and Heath, Vol. 1, page iv

The Photographic News (1879) Advertisement of auction of the property of Newbon and Harding, 113 Pentonville Road, Vol. 23, July 18 issue, page v

The Photographic News (1890) Advertisements from John J. Griffin and Sons, Vol. 34, May 9 issue and afterwards

The Photographic News (1890) “We are sorry to learn of the death of the veteran photographer, Mr. Vernon Heath, who passed away on Friday last, October 25th, at the age of seventy-six”, Vol. 39, page 704

The Photographic Journal (1883) Advertisement from Robert C. Murray, New series, Vol. 7, October 8, page viii

Photography (1892) “Mr. Robert C. Murray has started in business for himself at 8, Garrick Street, Covent Garden, London, W.C., his engagement with Messrs. Griffin & Sons having expired with the end of the year”, Vol. 4, page 59

Photography (1892) Vol. 4, page 331

Plunkett, John (2013) Murray, Richard (unknown) and Heath, Vernon (1819-1895), Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography, Taylor and Francis, pages 965-966

Probate of Robert Charles Murray (1918) “Murray Robert Charles of St Scholasticas Retreat Kenninghall-road Clapton Middlesex died 29 October 1918 Probate London 3 December to Jessica Mary Green (wife of Henry Edward Green). Effects £127 19s 6d”, accessed through ancestry.com

Public Health (1892) Advertisement from John J. Griffin and Sons, Vol. 3, August 13 advertiser

Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science (1867) A telescope lamp, New Series, Vol. 7, page 223

Taylor, Roger, and Larry J. Schaaf (2007) Impressed by Light: British Photographs from Paper Negatives 1840-1860, Yale University Press, New Haven, pages 324-325, and 352

Turner, Gerard L’E. (1989) Murray and Heath microscope, item 89, The Great Age of the Microscope, Adam Hilger, Bristol, page 101

Woodcroft, Bennett (1859) “John Newman, and John Frederick Newman, both of 122, Regent Street, in the County of Middlesex, Opticians, for an invention for ‘Improvements in spectacles’. Letters Patent sealed”, Chronological and Descriptive Index of Patents Applied for and Patents Granted, For the Year of 1858, Patent 647, March 27