James White Neville, 1840 - 1900

by Brian Stevenson and Howard Lynk

last updated April, 2010

James

Neville’s microscope slides are distinctively styled, and easily recognized by

the ornate patterns he applied to ringing cement. Neville was a professional japanner (lacquer painter), and

his artistic abilities obviously extended to many aspects of his life. Figure 1 illustrates examples of

Neville’s handiwork, ranging from simple to ornate. It is rare to find two slides on which he used the identical

pattern and color combination.

Figure 1. Examples of microscope slides

produced by James Neville. The

fourth slide from the left, top row, is ringed in a simple pattern, but can be

identified as being by Neville from his handwriting on the label. The seventh slide from the left, top

James White

Neville was born in Birmingham, England, during mid-summer, 1840, the third child

of Charles and Judith Neville. Father Charles was recorded on the 1841 census as being an artist,

although James’ marriage record described Charles as having been an optician. Between 1841 and 1849, the family moved

to Wolverhampton, Staffordshire. Charles died in 1849, leaving Judith to care for James, two

brothers and two sisters. The 1851 census records Judith as working as a

confectioner. The family’s economic situation at that time must have been reasonably

decent, as they employed a live-in general servant.

By the time of

the 1861 census, James was working as a japanner. He and most of his family

lived together in Aston, Warwickshire. Mother Judith did not report being

employed. Younger brother William worked as an optician. A third sister appeared

on this census, Helen, aged 5.

James married

Margaret Neill in 1866, at the Parish Church of Handsworth, Staffordshire. The

couple then moved in with Margaret’s mother, Hannah, in Birmingham. Hannah was

a pawnbroker, an occupation also attributed to Margaret on the 1851 census.

Hannah was recorded as being married, but her husband does not appear with the

family on any census. Margaret was born in Dublin, Ireland, so it is possible

that her father was still in that country, or travelling. James and Margaret

had seven children over the next decade.

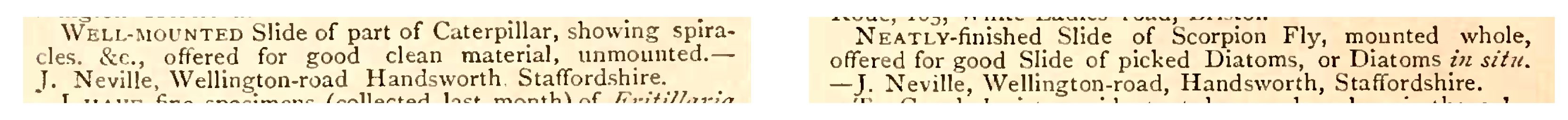

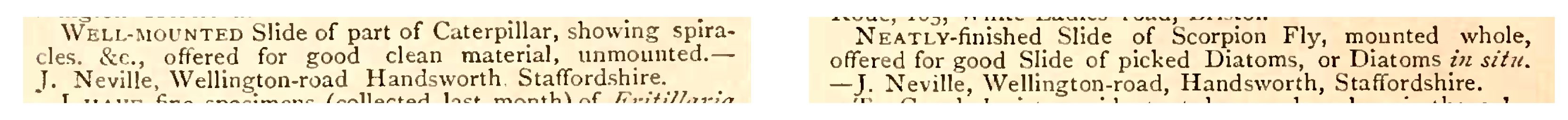

Neville

mentioned in an 1883 article that he had made slides using a particular method

seven years ago, indicating that he was seriously involved with microscopy by

1876. The earliest detailed record we found of James Neville’s interest in

microscopy were two 1878 exchange advertisements in Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip (Figure 2). He did not advertise in

earlier issues of this magazine, suggesting that had only recently achieved the

competence to produce high quality slides and the confidence to exchange them

with strangers. The descriptions he used for his slides, “well-mounted” and “neatly-finished”,

may indicate that he was already painting his slides with ornate ringing. As a

caveat, though, these were common phrases used by other slide makers to

describe their work, and may simply mean that he produced good-quality slides.

Figure 2.

Exchange offers from James Neville appearing during 1878 in “Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip”.

The following

year brought requests to exchange for slides of a dissected water beetle and a

whole-mounted spider. By 1880, Neville had joined the Birmingham Microscopists’

and Naturalists’ Union. For the next 11 years, The Midland Naturalist reported proceedings of the club’s meetings,

including descriptions of specimens exhibited under their microscopes. James

Neville was frequently noted as having exhibited microscopic, and macroscopic,

objects to his club. A list of microscopic specimens reported to be shown by

Neville at club functions may be found as Table 1, at the end of this essay.

This is an abbreviated description of his output, as many were listed as large

groups. For example, at the 1880

Annual Conversazione, Neville exhibited “150

slides of insects of the district”, and showed “100 slides of insects, mounted whole, and in dissected parts, also

tongue of spider” at the 1882 Conversazione. Moreover, Neville continued to

request slide exchanges for many years, so many of his works would have entered

the collections of other microscopists throughout the country.

Figure 3. Four microscope slides whose label descriptions correspond

with those known to have been exhibited by James Neville to the Birmingham

Microscopists’ and Naturalists’ Union. Left to right (descriptions are verbatim

from the “The Midland Naturalist”):

Bicillaria ciliata and Catenicella margaritacea, Australian polyzoa (both shown

Jan. 19, 1885); Section of Favosites forbesii, a fossil coral (Sept. 19, 1887); Parasite of tortoise (Oct. 26, 1891).

Neville served

as President of the Birmingham Microscopists’ and Naturalists’ Union in

1884. The following year, he

stepped down to become a Vice President. He also acted as the club’s Secretary

for many years. Neville’s’ presidential retirement address, "The Offensive and Defensive Weapons of Insects," was summarized in The Midland Naturalist,

and gives a good idea of James’ depth of knowledge: "remarking that as the subject was a wide

one, he should only take that part of it that referred directly to ourselves.

It might appear necessary to some to apologise for introducing into respectable

company some of the insects to which he should have occasion to refer. But

these would not be naturalists, for naturalists studied living objects as they

were, whether they pleased the sentiments or no. The offensive weapons of the

following insects were then referred to: Pediculus capitis, Nepa cinerea,

Notonecta glauca, Cimex lectularius, and Pulex irritans. The peculiarities of

their mouth organs were described and compared with a typical insect's mouth,

that of the ground beetle, Carabus, when the remarkable departure from a

probable original type was made apparent. In the latter part of the subject the

sting of the wasp was described with its complicated mechanism of poison bag,

duct with chitinous rings, pistons for ejecting poison, lancets, etc. The

address concluded by regretting that the labours of microscopists were often of

a desultory character, and pointing out the advantages of more special

pursuits. The use of the various forms and ornamentation of pollen grains was

suggested as good ground to be worked by microscopic botanists. The

Entomostraca, Diatomaceae, and Desmidiaceae of the district were mentioned as

fields of labour where good and useful work was required, and local catalogues

much needed. The address was illustrated by diagrams.”

Although he

was an amateur microscopist, James Neville developed considerable skill as a

slide mounter. He frequently

lectured to his club and wrote articles on mounting techniques. On October 11, 1885, “Mr. J.W. Neville demonstrated

the simplicity of preparing whole insects for investigation by describing and showing the processes they pass through.

Several objects were prepared and mounted, and afterwards exhibited to the meeting”. On September 22, 1890, "Mr. J.W.

Neville gave a short address on plant crystals and how to prepare them for the

microscope. The speaker said there was no royal road to mounting, and it was

impossible to mount a leaf to show its whole structure satisfactorily. In

mounting crystals we generally lost other cell contents, and in trying to

preserve the protoplasm of the cell we lost the crystals. The process

recommended was to bleach the leaves in chlorinated soda, and when quite

transparent mount in balsam through carbolic acid, and afterwards view with

polarised light. A collection of slides mounted in this manner was shown under

the microscope”. On July 13, 1891 he “gave

a demonstration of the use of carbolic acid in microscopic mounting. This is a

medium through which objects can be passed directly from water into Canada

balsam. Its use was particularly advantageous for objects that shrunk and

cracked in drying, and also for those that were difficult to rid of air, and it

was perhaps the most simple of the ‘wet methods’. A number of objects were then

mounted to show the process, a minute or two sufficing to transfer them from

water into balsam”.

He

wrote to The Midland Naturalist in 1883: “Many of the readers of the ‘Midland

Naturalist’ will learn with pleasure that there is such a ready way of mounting

vegetable preparations as that mentioned by Mr. Bagnall in the July number, as

the invention of Professor Hillhouse of the Mason College. The process is very

simple, and the medium excellent; but from practical experience I would suggest

the sealing of the cover-glass with pale copal varnish, instead of dilute

balsam; it can be obtained of as light a colour, is much tougher, and not

likely to get so brittle as that medium. As regards the newness of the invention,

I can only say I have preparations by me that have been put up in this way for

seven years or more, and several of my friends have used it as long a time,

preferring it to glycerine jelly, as it does not show such a disposition to

leak. Practical microscopists will, however, be glad to learn that after this

space of time the objects show no signs of deterioration, but rather wear an

improved appearance.”

During 1886,

Neville published in Hardwicke’s

Science-Gossip on “Wilks' Cell”. This invention, by George Wilks of

Manchester, was a grooved lead ring to be used as a spacer between a slide and

coverslip, for mounting large objects. The soft lead could be compressed to

reduce the depth, if necessary. “It is

somewhat difficult to give R.S.P. the information he seeks on the manner of

using the Wilks' cell, without first knowing how advanced he may be in the

preparation of objects without pressure. It requires a considerable amount of

care to get the objects ready for the cell, but when this is done the mounting

of them is the easiest part. If R.S.P. refers only to this latter part, he will

find no difficulty if he proceeds as follows. Take a cell and see that it is no

deeper than the object requires. If it is too deep it can easily be flattened

between two pieces of glass by pressure, until the exact depth is gained. All

that remains then to be done is to place it on a clean slip, fill it with thick

balsam, and, immersing the prepared object, put on the cover glass. In using

the thick balsam, numerous air bubbles will most likely appear in the cell.

This is a small matter, for if kept in a warm place they will gradually work to

the edge and disappear. If R.S.P. wishes for anything like full information on

the preparation of objects for the cell, I fear it cannot be given without

devoting at least one article to the subject. The Wilks' cell is a very useful

introduction, and deserves to be largely used. Prior to its invention I have

frequently extemporised one from a vulcanite cell, that sufficiently answered

the purpose, although at the cost of time and trouble. Still I think the cell

is open to improvement, and would suggest that it had at least twice the number

of elevations, or, perhaps better still, was corrugated, as in its present form

the cover glass is likely to get broken unless well banked up with edging

colour, as there is so large a space between the supports.” Neville was

also familiar with Wilks’ microscope slides, and on February 23, 1885,

displayed “twelve botanical sections,

double stained, prepared by Mr. G. Wilkes (sic)” to his microscopy club.

In addition to

microscopical preparations, James Neville exhibited a wide variety of natural

objects at meetings of the Birmingham Naturalists’ and Microscopists’

Union. On December 17, 1888, he showed

the skin of a large Australian snake. This is probably the same specimen he

advertised for exchange the following year “Offered,

skin of snake, ten feet long. Wanted, exotic insects or offers”. He is also

recorded as having exhibited tropical land shells, fossils in limestone,

ammonites, “leaves of Spircea Ulmaria

infested with brand”, and “a pansy

with six petals, an abnormal growth that has been continued on all off-sets for

several years”. Neville read several papers to the club, including “Peeps into Ponds” on Sept. 30, 1895, and “Protective Devices of Larvae” on June 26, 1899. Two other well-known microscope slide-makers, Herbert Darlaston and Richard Hancock, were also members of the club during those years.

On November 17, 1890, at the Union’s Annual Public Exhibition,

Neville exhibited “a frame of lantern

slides, illustrating the ‘Wonders of a Pond’”. These may have been his own

productions. In 1895, he published a small book, The Photographic Colourist: “a

manual for the use of amateurs: giving every particular required for painting

lantern slides and other transparencies, colouring diagrams, preparing lantern

slides without the aid of photography, blacking out backgrounds, scratching in

details, tinting paper prints, colouring paper prints to imitate oil paintings,

crystoleum painting etc. etc.”

James

Neville’s artistry extended well beyond decorating microscope and lantern

slides. One of his descendants, Faith Blancquiere, provided us with pictures of

a painting and two decorated silk cushions made by Neville (Figure 4). Undoubtedly,

many examples of his decorations of furniture, etc. remain, although it is very

likely that they were unsigned and remain anonymous.

Figure 4. Artworks by James Neville.

Top, framed painting. Bottom, two painted silk cushion covers. Photographs

provided by Faith Blancquiere.

James White

Neville died at the age of 59 on June 14, 1900, at his home on Wellington Road,

Handsworth. The cause of death was

recorded as “Malignant Sarcoma, Pulmonary

Haemorrhage, Syncope”. There is a strong possibility that his cancer was

brought on by a lifetime of inhaling fumes from the chemicals he used as a

japanner. It is ironic to think that each of his elaborately-decorated

microscope slides may have contributed to their maker’s early death.

Figure 5. Photograph of James White Neville, provided

by Faith Blancquiere.

Table 1. Microscopical preparations

exhibited by James W. Neville at meetings of the Birmingham Microscopists’ and

Naturalists’ Union, between 1881 and 1891. Neville was a sub-editor for The Midland Naturalist during

that time period, and regularly reported items displayed at meetings of his

society. This list describes only

some of Neville’s slides shown at club functions, as many were exhibited in

large groups that were not individually identified. He also traded extensively with other naturalists, and so

undoubtedly made many more slides than were exhibited at the club. Nonetheless, this list shows the

breadth to Neville’s interests in natural history, with specimens of all sorts

of animals, plants and minerals being represented. Descriptions in the table

are paraphrased from the published descriptions.

|

Antennum of butterflies and moths

|

March 16, 1891

|

|

Aphids

|

November 9, 1891

|

|

Aregma bulborum

|

August 31, 1885

|

|

Aregma bulbosa

|

May 26, 1884

|

|

Aregma obtusatum

|

June 23, 1884

|

|

Arran pitchstone, section

|

February 20, 1888

|

|

Astromyelon and particular woody tissue, from coal

measures

|

June 12, 1882

|

|

Australian sundew, leaf with captive insects

|

June 18, 1886

|

|

Australian tettigoinia larvae, found on the eucalyptus

tree

|

June 21, 1886

|

|

Batachospermum,

from Keeper’s Pool

|

March 18, 1881

|

|

Bicellaria

ciliata, Australian polyzoa

|

January 19, 1885

|

|

Bladderwort, Utricularia vulgaris

|

July 14, 1884

|

|

Bombyx mori

larva, mounted whole, showing tracheal system complete

|

September 5, 1881

|

|

Bombyx mori

larva, showing two rows of hooklets in each leg

|

October 2, 1881

|

|

Bombyx pernyi,

antenna

|

November 30, 1885

|

|

Brittle starfish, Ophiocoma neglecta

|

August 17, 1885

|

|

Butterfly wing, Morpho

cypris

|

June 15, 1885

|

|

Butterfly wing, Orthoptera

rhadamanthus

|

March 10, 1884

|

|

Calamite stem

|

April 25, 1881

|

|

Calamites, fossil, transverse section

|

December 15, 1884

|

|

Carchesium

polypinum

|

March 23, 1885

|

|

Catenicella

auritia, an Australian zoophyte

|

October 26, 1885

|

|

Catenicella

margaritacea, Australian polyzoa

|

January 19, 1885

|

|

Cement-stein from Isle of Fur, Denmark, showing Trinaeria excavata and other diatoms

in situ

|

February 15, 1886

|

|

Chaleis minuta,

from Turkey

|

November 29, 1886

|

|

“Cherry-gall” flies, Cynips quercus folii, male and female

|

August 18, 1884

|

|

Chiton cinercus,

palate

|

September 15, 1884

|

|

Cluster Cup and Coleosporum

on leaves of coltsfoot

|

September 19, 1881

|

|

Coal-ball section, showing a sporangium with spores in

situ

|

December 20, 1886

|

|

Coal ball section, with transverse section of Rachiopteris oldhamium

|

November 16, 1885

|

|

Coal from Hamstead, fibrous, showing dotted vessels

|

December 9, 1889

|

|

Coal section showing excreta of insects deposited in

the tissues of plants which they had eaten, probably while in the larval

stage

|

December 12, 1881

|

|

Coal sections, showing fern sporangia with spores in

situ

|

November 21, 1881

|

|

Coltsfoot leaf infested with micro-fungus (Coleosporum)

|

August 22, 1881

|

|

Comb-footed ichneumon fly, Ophion luteum

|

October 6, 1884

|

|

Cricket, chirping file and drum

|

October 3, 1887

|

|

Cuttle fish bone, section

|

November 23, 1885

|

|

Deutzia corymbosa,

leaf

|

June 25, 1888

|

|

Deutzia scabra,

leaf

|

June 25, 1888

|

|

Diatomaceae, from deposit in Black Root pool, Sutton

Park

|

November 3, 1884

|

|

Dog rose, section through a prickle

|

June 30, 1884

|

|

Doris flammea,

palate

|

September 22, 1884

|

|

Dragon-fly (Agrion),

jaws

|

July 10, 1882

|

|

Dredgings from “Challenger” Expedition

|

January 8, 1883

|

|

Dredgings from Indian Ocean

|

January 28, 1884

|

|

Drone Fly proboscis

|

September 25, 1882

|

|

Drosera

rotundiflora leaf, with captured insects

|

May 19, 1884

|

|

Dytiscus

marginalis, alimentary canal

|

July 28, 1884

|

|

Dytiscus

marginalis, elytra

|

April 20, 1891

|

|

Emperor Moth larva skin, which had been pierced by

Ichneumon Fly

|

June 26, 1882

|

|

Euplectella

aspergillum, spicules

|

October 18, 1886

|

|

Favosites

forbesii, a fossil coral, section

|

September 19, 1887

|

|

Ferns, fossil, from Albion

|

October 20, 1884

|

|

Fern fructification, fossil in a section of coal-ball

material

|

September 10, 1888

|

|

Fern, Rachiopteris

cylindrica, stem, transverse section

|

November 21, 1881

|

|

Flea, common, gizzard

|

August 25, 1883

|

|

Flea, common, lancet

|

August 25, 1883

|

|

Flea, common, stomach

|

March 27, 1882

|

|

Flint, section showing Xanthidia

|

August 21, 1882

|

|

Floral organs, sections, showing all the parts in situ

|

January 5, 1891

|

|

Flustra

episcopalis, from New Zealand

|

January 26, 1885

|

|

Foraminifera, dredged off the coast of Galway

|

January 5, 1885

|

|

Foraminifera from Borth

|

July 6, 1891

|

|

Foraminifera from Jersey

|

March 5, 1888

|

|

Foraminifera etc., from chalk washings

|

November 9, 1885

|

|

Foraminifera from sponge sand, selected

|

May 2, 1887

|

|

Funaria

hygrometrica, capsules

|

June 16, 1890

|

|

Fungus, paper mildew, Myxotrichum chartarum

|

March 31, 1884

|

|

Fusus islandicus,

palate

|

November 17, 1884

|

|

Fusus islandicus,

palate

|

October 24, 1887

|

|

Gamasus

coleoptratorum from humble bee

|

June 7, 1886

|

|

Gorgonia from Australia, spicules

|

April 4, 1887

|

|

Grasshopper, auditory organs

|

September 5, 1887

|

|

Gyrinus natator,

double eyes

|

October 24, 1881

|

|

Haliotis

tuberculata, lingual ribbon

|

December 4, 1881

|

|

Hedge Maple, transverse section

|

September 18, 1882

|

|

Helices, jaws, series on a single slide mounted for

comparison

|

February 21, 1887

|

|

Heliolites

interstinetus, section

|

May 18, 1885

|

|

Honey bee, antenna comb

|

April 12, 1886

|

|

Horned aphis, Cerataphis

lataniae

|

February 25, 1884

|

|

House fly, Musca

domestica, teeth

|

August 11, 1884

|

|

House spider dissections, showing falces, tongue,

&c.

|

February 6, 1882

|

|

Human colon, transverse section

|

April 24, 1882

|

|

Human lung

|

April 24, 1882

|

|

Hydrodictyon

utriculatum, water net

|

August 15, 1887

|

|

Hydrodictyon

utriculatum, in four stages of growth

|

March 17, 1890

|

|

Ilispa atra,

a spiny beetle from Turkey

|

August 23, 1886

|

|

Leaf crystals, treated with chlorinated soda, mounted

in balsam/carbolic acid, various

|

September 22, 1890

|

|

Lecythea on

leaves of barren strawberry

|

August 25, 1883

|

|

Lecythea and Aregma on leaf of barren strawberry

|

September 19, 1881

|

|

Lecythea or

rust on leaf of rose

|

September 19, 1881

|

|

Lepidodendron

bark

|

April 25, 1881

|

|

Lepidopterous larvae, 12 slides

|

September 2, 1889

|

|

Maize, annular vessels

|

June 8, 1891

|

|

Marchantia,

spores and elaters

|

July 18, 1881

|

|

Megalicthys,

head plate, from Lancashire coal beds

|

June 6, 1884

|

|

Melicerta ringens

|

June 15, 1891

|

|

Membranipora

membranacea, a polyzoan from New Zealand

|

January 12, 1885

|

|

Mica, showing dendritic crystals of manganese

|

April 4, 1881

|

|

Mole cricket gizzard

|

March 1, 1886

|

|

Mosquito, mouth organs

|

May 4, 1885

|

|

Moss fruits

|

January 4, 1886

|

|

Nassa reticulata,

palate

|

April 27, 1885

|

|

Nitella

translucens

|

May 23, 1881

|

|

Oak Apple fly, Cynips

terminalis

|

February 9, 1885

|

|

Oak Spangle fly, Cynips

longipennis

|

May 5, 1884

|

|

Octopus palate

|

June 29, 1885

|

|

Ocypus olenus

beetle, mouth organs

|

September 2, 1889

|

|

Oidium moniliodes,

on leaves of grass

|

August 25, 1883

|

|

Ophiocoma

neglecta

|

May 12, 1884

|

|

Orgyia pudibunda,

larva, mounted whole, popularly known as the Hop Dog

|

February 2, 1885

|

|

Oysters, young shells

|

March 7, 1881

|

|

Parasite of Limax

flavus

|

July 30, 1888

|

|

Parasite

of tortoise

|

October

26, 1891

|

|

Pediculus capitis,

tracheal system

|

November 26, 1888

|

|

Pelopaeus

fistularis, a mason-wasp from Constantinople, mouth organs

|

January 17, 1887

|

|

Permian marl, with fern impressions

|

December 22, 1884

|

|

Phlota plumosa

|

June 26, 1882

|

|

Phragmidium

obtusum on leaves of barren strawberry

|

August 25, 1883

|

|

Pinguicula

vulgaris leaf, with insects

|

September 7, 1885

|

|

Piniperda

larva

|

August 11, 1883

|

|

Plant bug, Tingis,

from Turkey

|

September 20, 1886

|

|

Plant bug, Tingis,

from Turkey

|

October 15, 1888

|

|

Plocamium

coccineum in fruit

|

April 3, 1882

|

|

Polyxenes lagurus

|

April 19, 1886

|

|

Puccinia on

leaf of violet

|

September 19, 1881

|

|

Pulex irritans,

striated muscles

|

February 7, 1887

|

|

Ranunculus repens

leaf, showing aecidium in situ

|

June 18, 1883

|

|

Ruby sand with fluid cavities, from New Zealand

|

July 27, 1885

|

|

Sea mouse, hair

|

May 1, 1882

|

|

Shells from the Gulf of Aden

|

April 13, 1891

|

|

Sirex gigas,

ovipositor

|

July 27, 1891

|

|

Sheep tick, Ixodes

reduvius

|

December 7, 1885

|

|

Snake’s head coralline (Anguinaria spathulata)

|

February 4, 1884

|

|

Sugar-cane, transverse section

|

November 28, 1881

|

|

Synapta adherens,

skin, showing anchors and plates in situ

|

February 20, 1882

|

|

Testacella

haliotidea, palate

|

April 18, 1887

|

|

Trachea, from larva of drinker moth

|

July 21, 1884

|

|

Trochus,

palate

|

September 4, 1882

|

|

Trochus,

shell

|

September 4, 1882

|

|

Volvox globator

|

April 20, 1885

|

|

Wasp, mouth organs, mounted without pressure

|

March 9, 1885

|

|

Wasp queen, mouth organs

|

March 23, 1891

|

|

Water spider, tongue

|

October 17, 1881

|

|

Worm-eaten glass, from an old Warwickshire church

|

July 2, 1883

|

|

Yoredale limestone, section, with goniatites in situ

|

September 29, 1884

|

|

Zonites

draparnaldi, palate

|

January 3, 1887

|

Acknowledgements

We thank Faith

Blancquiere for her generosity in providing information on James Neville and

pictures of him and his work. It was a pleasure to assist her with new

information on her ancestors. We also thank Maureen Carter for providing

information on Neville and his associates at the Birmingham Naturalists’ and

Microscopists’ Union.

Resources

Bracegirdle,

Brian (1998) Microscopical Mounts and

Mounters, Quekett Microscopical Club, London.

Death record of James White Neville.

English

census, birth, marriage, and death records, accessed through www.ancestry.co.uk

Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip, vol. 14

(1878), Exchanges column, pages 168 and 216.

Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip, vol. 15

(1879), Exchanges column, pages 168 and 264.

Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip, vol. 19

(1883), Exchanges column, page 264.

Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip, vol. 24

(1888), Exchanges column, page 120.

Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip, vol. 25

(1889), Exchanges column, page 168.

Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip, vol. 27

(1891), Exchanges column, page 192.

Kelly, E.R. (1879) Post

Office Directory for Birmingham, with it Suburbs, page 245.

The Midland Naturalist,

vols. 3-14 (1880-1891) Birmingham Naturalists’ and Microscopists’ Union

proceedings, numerous pages. Details of specimens exhibited by Neville and

other club members.

The Midland Naturalist,

vol. 7 (1884) Birmingham Naturalists’ and Microscopists’ Union, page 852.

The Midland Naturalist,

vol. 8 (1885) Our sub-editors, page 28.

Neville, James W. (1883) New methods of mounting for the

microscope, The Midland Naturalist,

vol. 6, page 190.

Neville, James W. (1885) Crystals for the polariscope, Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip, vol. 21,

page 115.

Neville, James W. (1885) Abegma bulbosum, The Midland Naturalist, vol. 8, page 297.

Neville, James W. (1886) Wilks’ cell, Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip, vol. 22, page 233.

Neville, James W. (1895) The

Photographic Colourist, Iliffe and Son, London.

Yearbook of the

Scientific and Learned Societies of Great Britain and Ireland (1884) The

Birmingham Naturalists’ and Microscopists’ Union, page 71.

Yearbook of the

Scientific and Learned Societies of Great Britain and Ireland (1895) The

Birmingham Naturalists’ and Microscopists’ Union, page 105.

Yearbook of the

Scientific and Learned Societies of Great Britain and Ireland (1900) The

Birmingham Naturalists’ and Microscopists’ Union, pages 116-117.