Benjamin Wills Richardson, 1819 - 1883

"B W R"

by Brian Stevenson

last updated December, 2018

Microscope slides by Benjamin Wills Richardson are occasionally encountered, most with his initials written on the ringing or engraved into the glass, although some are known with his name spelled out (Figures 1-3). Richardson was a surgeon, medical author and artist, and inventor of medical instruments. He was also a microscopist with a wide array of interests, and a member of the Dublin (Ireland) Microscopical Club. The British Medical Journal described him as “one of the first Dublin professional men to use the microscope scientifically; and he possessed considerable manipulative skill in its use and in mounting preparations”. Richardson shared his works with the Quekett Microscopical Club, and probably other groups and individuals.

Another man with a similar name, Benjamin Ward Richardson (1828-1896), was a well-known physician in London and member of the Royal Society. It may be that most publications refer to our microscopist as “B. Wills Richardson” in order to avoid confusion with the other man. Although Benjamin Ward Richardson published extensively on medical matters, none of his writings indicated an interest in microscopy. In contrast, Benjamin Wills Richardson provided extensive evidence of avidity for the microscope, leaving little doubt that he was associated with the slides shown in Figures 1, 2 and 3.

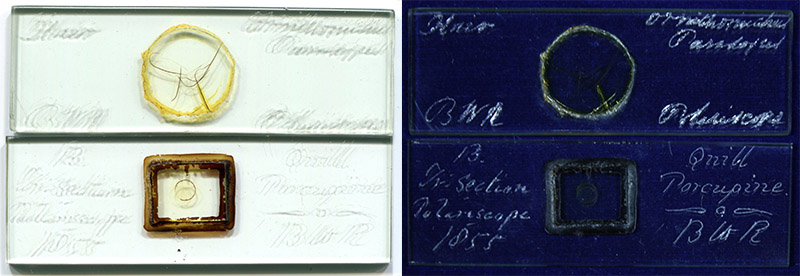

Figure 1.

Two slides by B. Wills Richardson, both with his initials and descriptions written on the “ringing” that sealed the coverslips. (A) Electric organ of a ray, 1876, shown as a flatbed scan and a photograph against a black background. It is engraved “B. Wills Richardson to Royal Mic Society” and “1 inch objective”. This slide is also shown in Brian Bracegirdle’s “Microscopical Mounts and Mounters” in Plate 30-Q. (B) Longitudinal section through a human uterus, dated 1878. Image adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

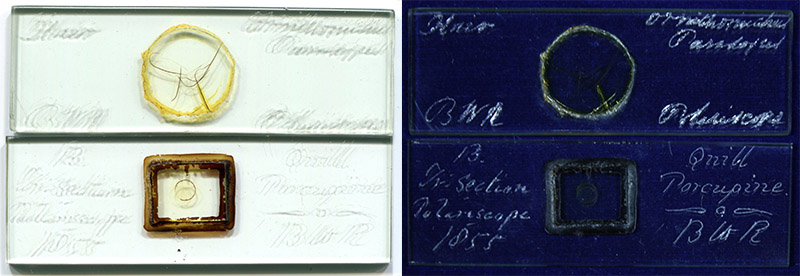

Figure 2.

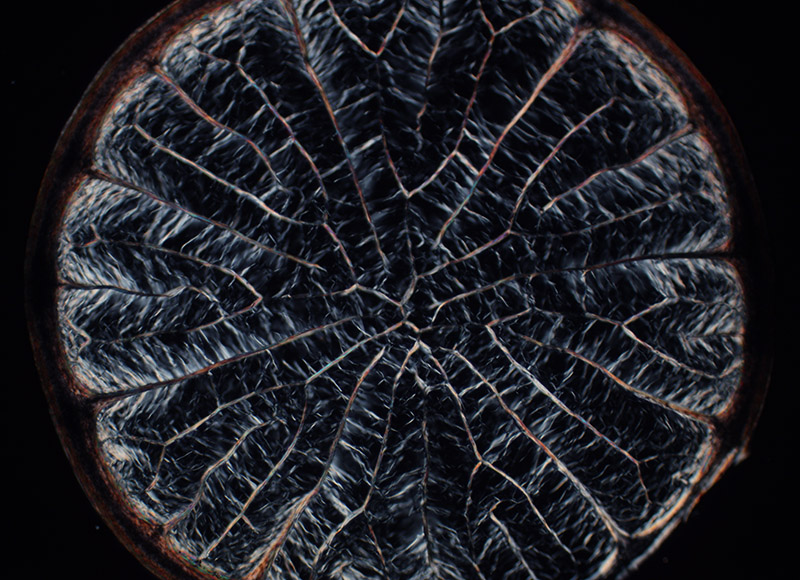

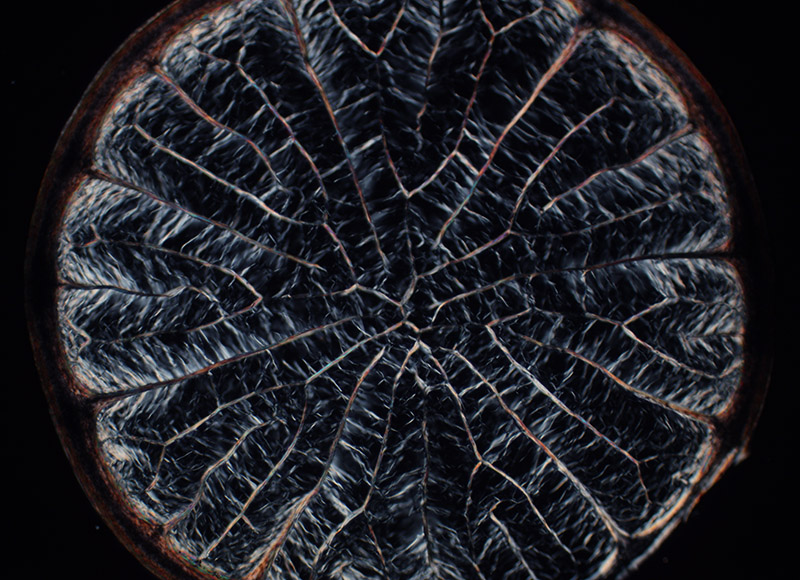

Two microscope slides by B. Wills Richardson – hairs of “Ornithorinchus paradoxes” (sic, Ornithorhynchus paradoxus, the platypus), and transverse section of a porcupine quill. The porcupine quill slide is dated 1855. Both were marked as intended for polariscope viewing. Richardson used very thick glass for these slides, and engraved his initials and specimen descriptions into the glass.

Figure 3.

Two additional slides signed by B.W. Richardson, both dated 1862. The left slide resembles the anatomical mounts of Karl Thiersch, several of which are known to have been owned by Richardson. These slides are currently in the collection of the Quekett Microscopical Club. Image adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes.

Little is known about Richardson’s early years. All known records list him as a resident of Ireland, suggesting that he was born there. His 1883 obituary states that he was then 64 years old. Bibliographies of his writings give a lifespan of 1819-1883, consistent with his age at death. Richardson’s marriage record gives his father’s name as William. Richardson paid a subscription to help publish Thomas Burke’s 1840 book on midwifery, wherein he is listed as living at 17 Upper Gardiner Street, Dublin. Records from 1838 and 1846 list a barrister named Anthony Wills as living at that same address. Will’s surname suggests that he was related to Benjamin Wills Richardson. Of note, Anthony Wills was of a scientific bent, and a member of the British Association for the Advancement of Science.

Richardson studied medicine at the Richmond Hospital, Dublin. He became a Licentiate and Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons of Ireland in 1844.

On April 18, 1848, Richardson married Rosamund Melesina McClintock. The couple had 10 children: 6 boys and 4 girls.

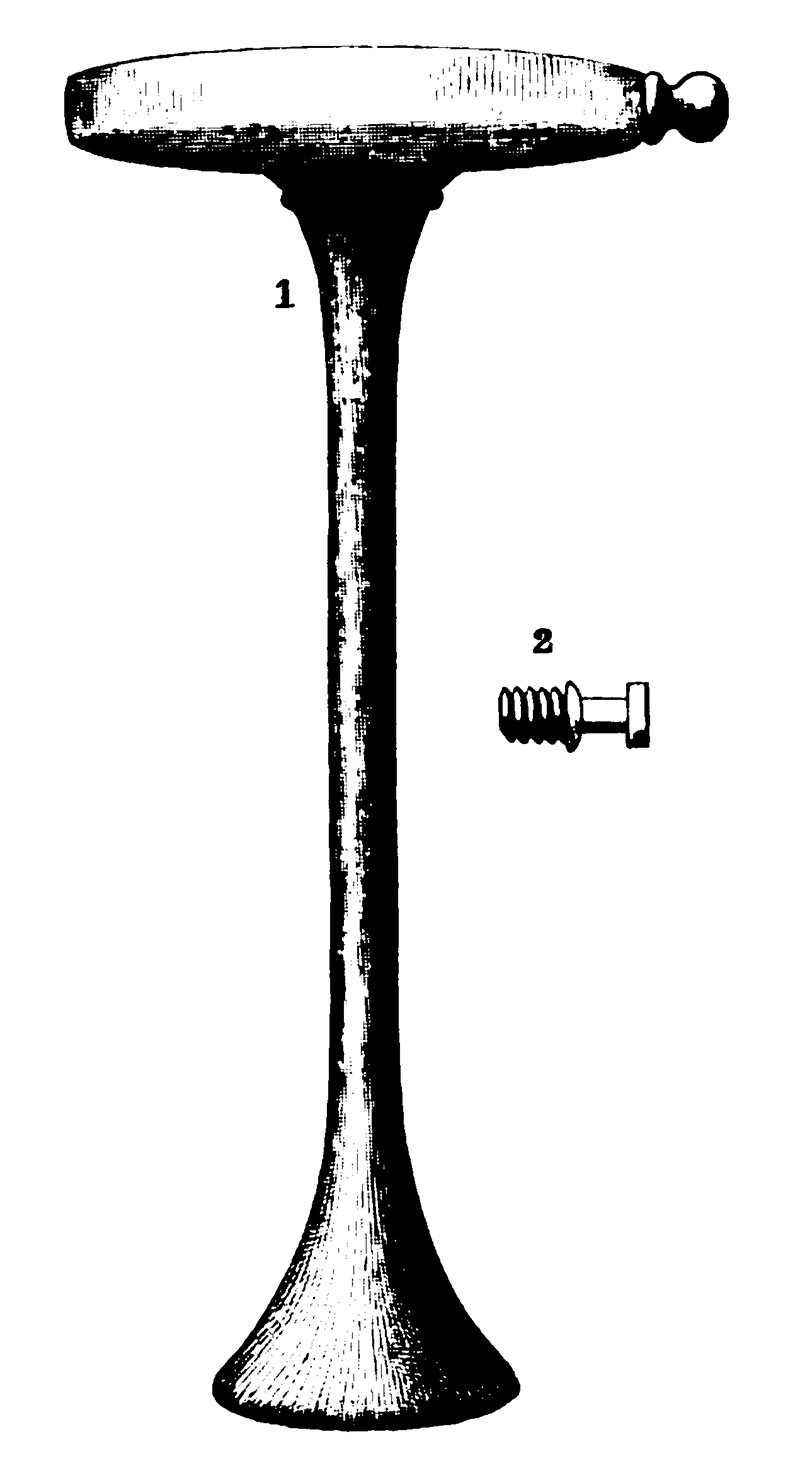

The surgeon began making an impact on medicine early in his career. In 1851, Richardson published a description of his new form of stethoscope, an illustration of which was published in 1854 (Figure 4).

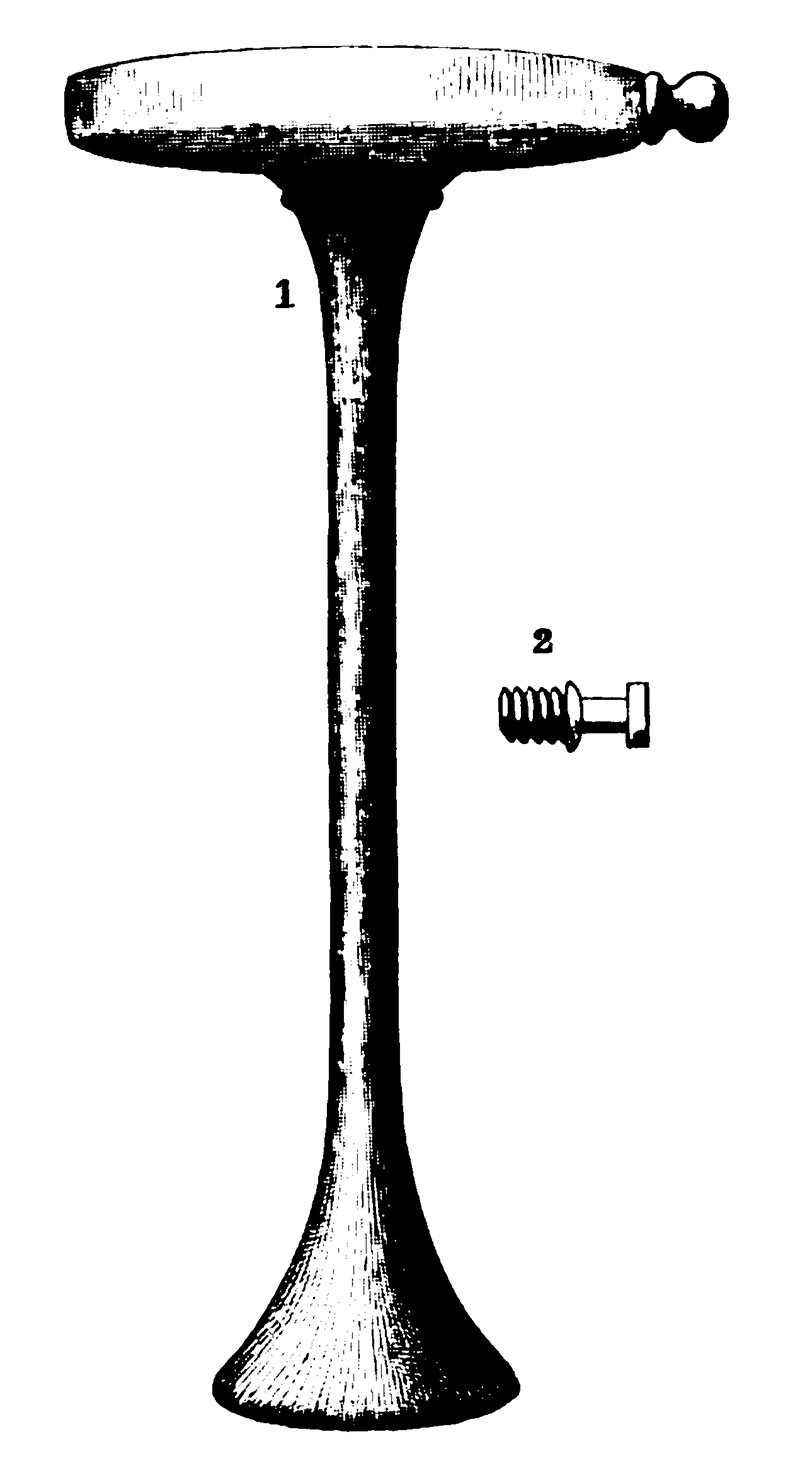

Figure 4.

Richardson’s percussor stethoscope, as published in 1854. Considering Richardson’s artistic skills, it is likely that he drew the original picture.

The 1853 Medical Directory of Ireland reported that Richardson had moved to 2 North Frederick Street, in Dublin. It also states that he was then Assistant Medical Officer of the South Dublin Workhouse and a member of the Surgical Society of Dublin, and formerly Demonstrator of Anatomy at the Richmond Hospital School of Medicine.

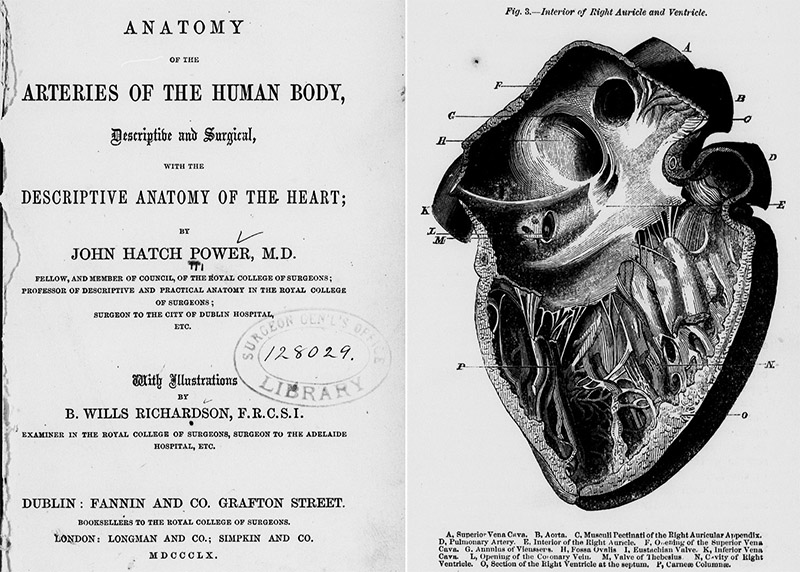

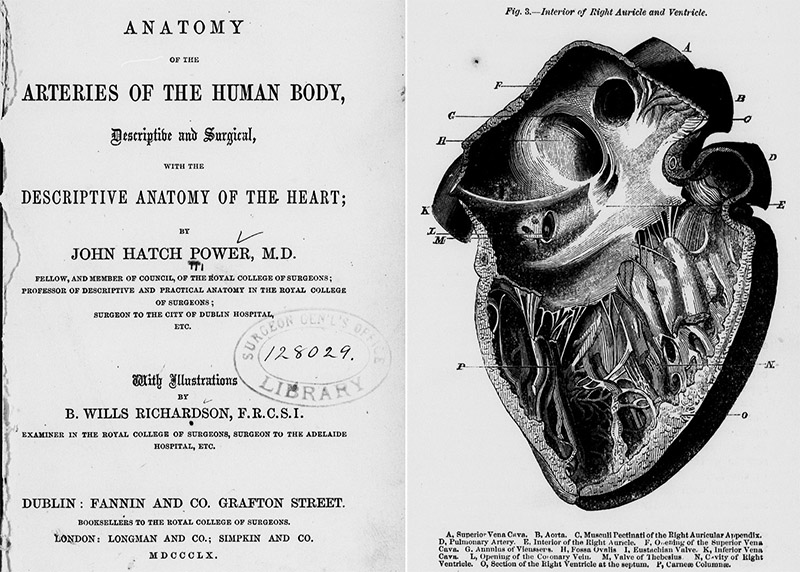

Richardson was a skilled artist, and provided the illustrations for John Power’s 1860 book on the human heart and arteries (Figure 5). That work also indicated that Richardson was then Surgeon to the Adelaide Hospital and an Examiner for the Royal College of Surgeons.

Figure 5.

Title page and example illustrations from Power and Richardson’s "Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body: Descriptive and Surgical, with the Descriptive Anatomy of the Heart".

In 1862, Richardson wrote to the Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science, regarding the microscope slides of anatomical subjects that were being produced in Germany by Karl Thiersch and retailed by Smith, Beck, and Beck. Thiersch’s mounts were often of dimensions significantly different than the English standard 3 x 1 inch. Richardson reported that he dealt with fitting these awkwardly-sized slides into his cabinets by remounting them onto different, standard-sized slides: “Transparent Carmine Injections - I have found no difficulty in remounting the transparent carmine injections, and did so with all of the kind in my collection. If the broad slide is the proper length - above three inches - your correspondent's advice, in your last volume, may be followed by cutting with the diamond to the necessary width and length; but I prefer the remounting, particularly when the German slide is shorter than three inches”. The left slide illustrated in Figure 2, above, is probably a Thiersch preparation that was trimmed to a 1 inch width by Richardson. The paper edging likely covers the rough glass from his modifications.

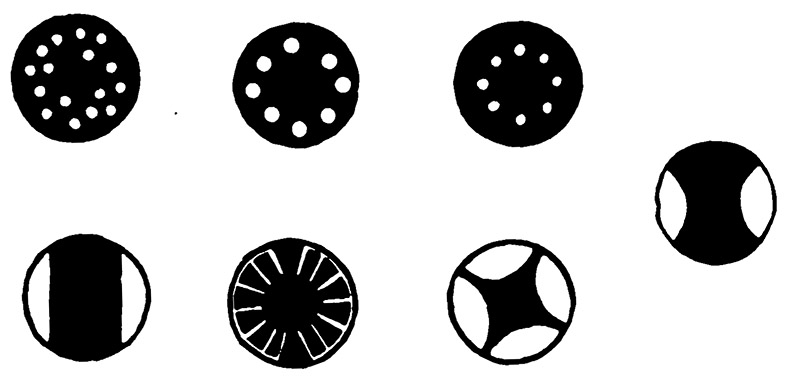

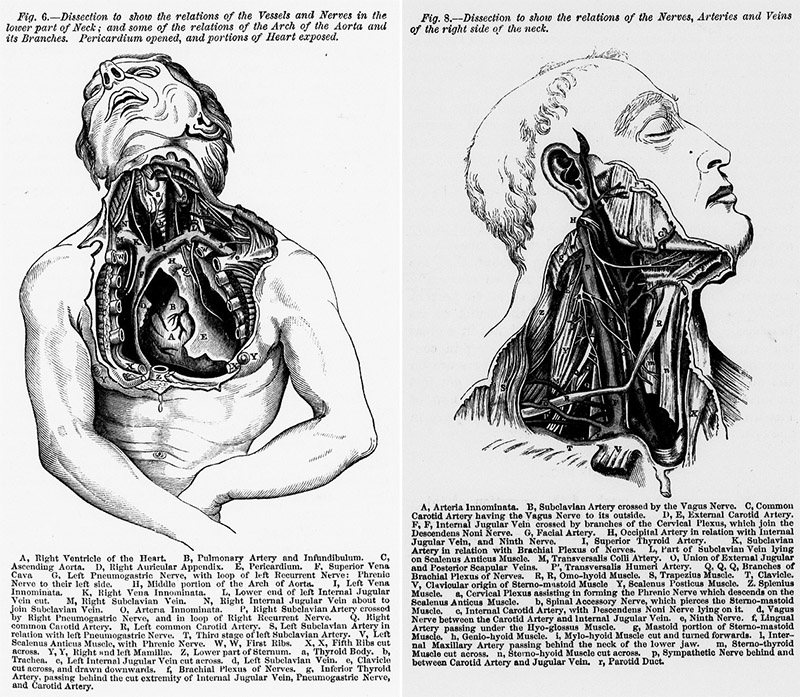

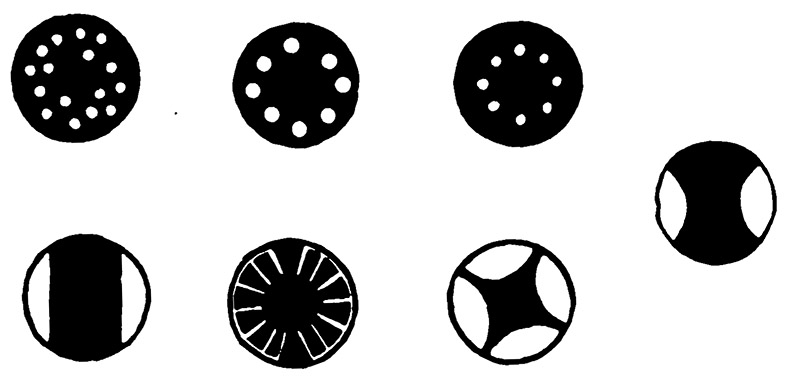

Richardson again wrote to the Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science, in 1866, on a series of stops that he devised for viewing diatoms by oblique illumination (Figure 6). He also provided information on his preferred microscopical equipment, “After numerous trials I was successful in forming some stops for my Smith and Beck's achromatic condenser, with the assistance of three of which, in particular, the markings of many diatoms requiring oblique illumination can be quickly and beautifully exhibited, and with a field, I may say altogether, free from the glare and milkiness so often experienced with the mirror, as well as with the prism … As the only high powers of English makers I have used were the 1/5th and 1/8th of Smith and Beck, I cannot, of course, say how the stops would act with their higher objectives, or with the glasses of other English opticians; but I can confidently recommend the second, third, and sixth particularly to those microscopists who possess Smith and Beck's powers above mentioned, for to my eye, at least, the definition of their 1/5th and 1/8th with those stops could scarcely be exceeded”. On a related vein, the 1873 records of the Dublin Microscopical Club report that, “Dr. Richardson showed a so-called 1/24th of Gundlach's, on some difficult diatoms, which seemed to perform very well”.

Figure 6.

Stops designed by B. Wills Richardson for use with a Smith & Beck achromatic condenser, to illuminate structures of diatoms.

On November 23, 1867, the Quekett Microscopical Club received a donation of “a box of slides from W.B. Richardson, Esq., F.R.C.S.I., of Dublin”.

Richardson exhibited “several slides of the salts of xanthine” to the Dublin Microscopical Club, in 1873. He stated, “For the opportunity of examining microscopically some of the salts of xanthine I am indebted to the kindness of Dr. Neubauer, of Wiesbaden, who sent me a specimen of xanthine from urine, as well as one prepared artificially from guanine. As urine, according to Dr. Neubauer, contains only about one gramme of xanthine in 600 pounds; my obligation to him is therefore not an inconsiderable one”. Richardson later exhibited, in 1876, a slide of xanthine sulphate crystals that had been painstakingly prepared, “he placed about a quarter to half a grain of the xanthine on an ordinary slide, and then added to it a little pure sulphuric acid. The slide was placed in a cabinet, secured from dust. Crystallization slowly took place which ended in the formation of the very perfect stellate mass now under the microscope. It was not until the expiration of two years that the specimen was sufficiently dry to allow of his mounting it in Canada-balsam. During the slow process of drying, if it could be called such, he occasionally removed superfluous acid with small pieces of bibulous paper. The crystalline mass was globular and studded with long projecting crystals, some of which were facetted and appeared to belong to the triclinohedric system … In the polariscope, with the assistance of selenite, the polariscopic effect was very beautiful”.

�������������������������������������������������

Also in 1873, he displayed “Amoeboid movements of corpuscles of frog's blood - Mr. B. Wills Richardson made a very satisfactory demonstration of the 'amoeboid' movements of the white corpuscles of the frog's blood and of the corpuscles charged with refractive granules. The movements were truly amoeboid and highly characteristic; the refractive granules likewise were seen in active motion in each amoeboid mass containing them. Several of these were seen to move across the field, and in doing so passed, on more than one occasion, either over or under stationary red blood-corpuscles. Two of the granule-containing amoeboid corpuscles, when moving in opposite directions across the field, came in contact with one another. Their apposed surfaces then became parallel, and the corpuscles themselves were carefully watched by some of the members present to see if they would ‘conjugate’ or coalesce. Instead of doing so, however, they immediately separated, and each retraced its course to the portion of the field whence it came. The stage used for the occasion was an ordinary Strieker's hotstage, made and slightly modified for Mr. Richardson by Spencer, of Grafton Street, Dublin. The blood, when taken from the frog, was at once placed on the glass and with a very thin cover. To prevent evaporation a little spermaceti oil was applied with a fine sable pencil to the margin; this was done sparingly and very carefully, in order that the oil might not run in. The objective used was 1/8” Ross, but probably a 1/10” or 1/12" would be a better power for demonstrating the movements of the refractive granules to those who might be inexperienced in microscopical observation”.

Richardson mounted numerous anatomical subjects, as might be expected. For example, in 1880, he showed the Dublin Microscopical Club a “Section of larynx of human foetus: Mr. B. Wills Richardson exhibited with a Quekett's dissecting microscope and one of Charles Baker's 2-inch objectives only, so that the whole of the object might be seen, a cross section of the larynx of a nine months human foetus. In the specimen the most striking structures were (1) sections of the thyroid and the arytenoid cartilages; (2) the laryngeal pouches; (3) the pharynx; (4) portions of some of the intrinsic muscles of the larynx; (5) the laryngeal columnar epithelium; and (6) mucous glands. The specimen was a triple staining made with carmine, picric acid, and madder, the latter being an excellent medium for staining cartilage cells, their nuclei and nucleoli. The section was a striking illustration of the great assistance that may be derived from the use of the freezing microtome in minute anatomical research, for it is difficult to conceive that so even a section could be made without the greatest difficulty by any other methods with which we were familiar. Moreover, Mr. Richardson observed that scarcely a bit of the larynx was wasted, as he succeeded without any trouble in cutting the whole of it, the tenuity of all the sections being about the same as the one he exhibited. It was mounted in Klein's dammar solution”.

Figure 7.

A Quekett-pattern dissecting microscope, produced by William Ladd of London, similar to that used by B. Wills Richardson in 1880 to demonstrate sections of a human fetal larynx.

On January 27, 1882, the Surgical Society of Ireland toasted their colleague: “It affords me the great gratification of acting as your mouth-piece in expressing to my old friend and colleague, Benjamin Wills Richardson, our best feelings of heartfelt esteem and affection. The importance to such a Society as ours of an efficient, able, and courteous Secretary can scarcely be over-estimated. We all know that authors are proverbially sensitive, and sometimes when the productions of their genius are brought forward for publication here or elsewhere, it may be a difficult matter, requiring a great deal of tact and temper, to arrange the knotty points that arise. We also know what a trifle would turn the scale with all of us between the trouble of writing out our cases and presenting them here, or preparing a paper and declining to do so. But to overcome all these difficulties and objections the duty devolves on the Secretary, who must not on any account ever be tired or cross, and must always be goodtempered, courteous, efficient, and firm. Such was the office Mr. Richardson undertook to fill for this Society twenty-five years ago; and I may say that it is to mark their appreciation of the manner in which he has performed his task that the members of the Society desire to make him a presentation to-night. He proved himself invariably punctual, business-like, courteous, and firm, combining in a remarkable degree the suaviter in mode with the fortiter in re. How far the success of the Society may have depended on his exertions during the long period of his tenure of office it would be hard to say; but having been associated with him for many years in another institution, I must decidedly say that a more thoroughly practical, able, courteous, and efficient Secretary it would be impossible for us to secure. And now, Mr. Richardson, it becomes my pleasing duty, which, as I have already stated, I am gratified to be in a position to perform, to ask your acceptance of this service of plate which the members of the Surgical Society of Ireland desire to present as a small token of their heartfelt esteem and affection, and, at the same time, to express through me their earnest wishes for your health and happiness”.

Richardson died on April 29, 1883. Obituaries summarized his professional life:

British Medical Journal: “We regret to announce the death, on Sunday, April 29th, in the 64th year of his age of the above well-known Dublin surgeon. The immediate cause of his death was, we believe, Cardiac asthma; but his friends and acquaintances had noticed that for some time past he had been looking far from well, although he had recently performed his arduous duties as chairman of the Court of Examiners at the Royal College of Surgeons without making any complaint as to his heath. Mr. Richardson filled this post for a great number of years, and kept the minutes of various examinations I a manner which it will be difficult for his successor to emulate. He was for twenty-five years one of the honorary secretaries of the late Surgical Society of Ireland, and on his resignation of that office in 1881 was presented with a service of plate by the members, in recognition of his long and valuable services to the Society. Mr. Richardson was also one of the surgeons of the Adelaide Hospital since the year 1858. But although an able and remarkably well-informed surgeon, he did not succeed in obtaining that large share of private practice to which his ability fairly entitled him. His mind seemed to tend more to criticism, to minuteness and neatness in his work, and to almost painful accuracy in observation, than to take that broad and comprehensive view of nature and of disease, which goes far in securing the foremost position. Mr. Richardson was, we believe, the writer of many of the long critical and analytical reviews of surgical works which appeared in the Dublin Journal of Medical Science, and which exhibited his intimate acquaintance with French and English surgical literature. He contributed several original articles to the same journal, as well as to its contemporaries, and also introduced several instruments for the treatment of stricture of the urethra - a subject in which he took much interest - as well as a tubular presse artere, and an ether inhaler. He was one of the first Dublin professional men to use the microscope scientifically; and he possessed considerable manipulative skill in its use and in mounting preparations. Mr. Richardson filled all the positions he occupied with tact, ability, and efficiency. His loss will be much felt in his college and in his hospital, and by all those who were brought into contact with him and knew his worth”.

The Medical Times and Gazette: “After a long and painful illness, this well-known surgeon died at his residence, 22, Ely-place, Dublin, on Sunday, April 29. Up to the time of his death, Mr. Richardson occupied posts of trust and honour in the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, which he joined as a Licentiate and Fellow in the year 1844. He was Senior Examiner in Surgery and in Dental Surgery, and had for many years sat on the Court of Examiners in the College. When a young man, Mr. Richardson acted as Demonstrator of Anatomy in the Richmond Hospital (afterwards called the Carmichael) School of Medicine. He subsequently became Surgeon to the Adelaide Hospital in Peter-street, where he did much good work during many years. Mr. Richardson possessed inventive powers of no mean order, and among the instruments he devised mention may be made of a dovetailed stricture dilator, the dovetailed urethrotome and urethrometer (a bulbed stricture sound, of which the object was to sound a stricture from behind forwards), the tubular presse-artere, a modification of Ricord's phimosis forceps, a modified American apparatus for the treatment of fractures of the shaft of the femur, besides various new ether-inhalers. In the Dublin Monthly Journal of Medical Science for December, 1876 (vol. Ixii.), he published a description of a carbolic spray apparatus worked with the foot and Fletcher's bellows. Although he never wrote a book, Mr. Richardson was the author of many papers on pathology and operative and clinical surgery in tie medical periodicals. To the pages of the Dublin (Quarterly) Journal of Medical Science he contributed articles on ‘Slow Pulse and Fatty Degeneration of the Heart’, and on ‘Fatty Degeneration of the Kidney and Liver, with Observations on the Supposed Uraemic Poisoning’. At a time when histology and microscopic pathology were scarcely known as branches of medical science, Mr. Richardson had gained a reputation as a skillful microscopist, and to the last he found pleasure in histological and pathological research. So lately as the year 1881 he described in the Journal of the Royal Microscopical Society a method of staining sections of the spinal cord, and of animal and vegetable tissues. For many months before his death Mr. Richardson had been in delicate health, the affection from which he suffered being recognised as dilated aorta. At the time of his death he was sixty-four years of age”.

The Medical Press: “This widely-esteemed surgeon died at his residence, 22 Ely Place, Dublin, on the 29th ult, having endured much suffering from cardiac disease. After prolonged study in the Richmond Hospital, be became a Licentiate of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1844, and during the same year, under the Charter then granted, proceeded to the Fellowship. He was soon elected Demonstrator of Anatomy in the Richmond School; but the study of pathological anatomy and practical surgery absorbed his attention, unusual facilities of study then being afforded him in the South Union workhouse hospital, in conjunction with his friend Dr. Robert Mayne, who soon afterwards gained such deserved fame as a consulting physician. In 1866, Dr. Richardson was elected one of the Examiners of his College, and this position he held until his decease, having been for eight years the Senior Member and Recorder of the Court. So admirably were the practical and administrative duties of this office conducted, that it will be scarcely possible to find a fitting successor, and in the vote of condolence to his family unanimously passed at the special meeting of the College on last Saturday, it was truly stated that his knowledge of his subject was only equalled by his impartiality and urbanity. In two other positions which he held for more than a quarter of a century he will be long and affectionately remembered, viz., the Secretaryship of the Surgical Society, in which he followed Dr. Bellingham, and the Surgeoncy of the Adelaide Hospital. His devotion to the honorary functions of the former office induced the members to present him with an address and service of plate during January last year; it was then truly said ‘that a more thoroughly practical, able, courteous, and efficient secretary’ could not have been had. In his hospital he was always a punctual, willing, and reliable colleague, devoting himself especially to improvements of surgical apparatus. Of these, the best known is the dovetail dilator for urethral stricture, which is pictured in Bryant's Surgery, and highly approved of in that and other systematic works. He was always foremost in adopting the practical suggestions of others, and was, for instance, the first surgeon who used the wooden lever for compressing the iliac in hip amputation after its inventor, Mr. Davy. The numerous hospital reports Dr. Richardson submitted to the Surgical Society always excited interest, and in his communication in 1868 to the Medical Council on the course of study, he anticipated many of the points of the new scheme now under trial in the Irish College. Long before the microscope became fashionable he was an ardent and skilled histologic, and he attained considerable skill as an artist and wood engraver. The illustrations in the second and third editions of ‘Power on the Arteries’ were executed by him or under his superintendence. His papers on the Minute Anatomy of the Kidney, and the Modes of Staining Sections, are of great value. Spending his leisure in such occupations, instead of in the ways more usually followed for attracting public patronage, Dr. Richardson never attained that position as a practitioner which his very remarkable ability and high social standing must have otherwise gained. He was nearly allied to such leading families as the Humes of Humewood, and by his wife (the sister of Sir Leopold McClintock, and of Dr. McClintock, late President R.C.S.), with the noble family of Rathdonnell. Two of Dr. Richardson's sons became Licentiates of his College; the elder holds a surgeoncy in the Royal Navy; the younger, after a most promising studentship, died a few months since. This trial tended much to hasten the fatal illness of the lamented member of our profession whose career we have striven to briefly sketch”.

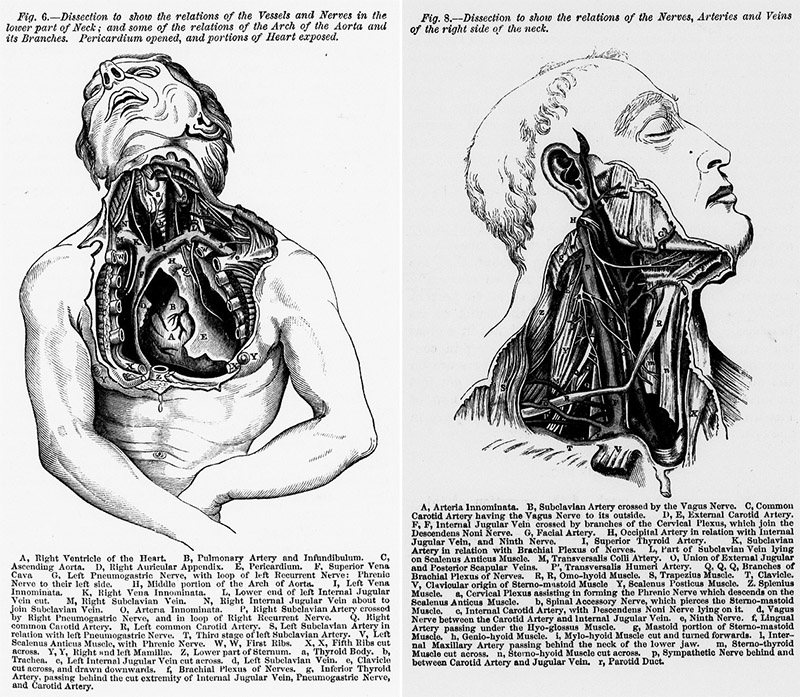

Figure 8.

Cross-section of a porcupine quill, prepared in 1855 by B. Wills Richardson. Photographed using crossed polarizing filters, with a C-mounted digital camera on a Leitz Ortholux II microscope with 3.4x objective lens.

Resources

ancestry.co.uk

Bracegirdle, Brian (1998) Microscopical Mounts and Mounters, Quekett Microscopical Club, London, pages 79 and 164, and plate 30-Q

British Medical Journal (1883) Obituary of Benjamin Wills Richardson, Vol. 1, pages 941-942

Burke, Thomas Travers (1840) The Accoucheur’s Vademecum, or, Modern Guide to the Practice of Midwifery, Simpkin, Marshall, and Co., London, Subscribers: “Richardson, Benjamin Wills, Esq., 17 Upper Gardiner-street, Dublin”

Dublin Almanac and General Register of Ireland (1848) “Richardson, Benjamin Wills, F.R.C.S.I. 17 Gardiner street, Upper”, page 570

Lynk, Howard (2012) The 1860s Smith, Beck & Beck transparent injections, Quekett Journal of Microscopy, Vol. 41, pages 701-712

Markham, Clements R. (2014) Life of Admiral Sir Leopold McClintock, Cambridge University Press, page 5: “Rosa Melesina, married to B. Wills Richardson, of Dublin”

Marriage record of Benjamin Wills Richardson and Rosamond Millsina (sic) McClintock (1848) accessed through https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:FG69-XH2

Medical Directory of Ireland (1853) “Richardson, Benjamin Wills, 2, North Frederick-st. Dublin - F.R.C.S. Ireland, 1844; Assist. Med Off. South Dub. Workhouse ; formerly Demonst. of Anat. Richmond Hosp. School of Medicine; Mem. Surg. Soc. Dub.”

The Medical Press and Circular (1882) Minutes of the Surgical Society of Ireland presentation to Mr. B. Wills Richardson, Vol. 33, pages 164-165

The Medical Press (1883) Obituary of Benjamin Wills Richardson, page 414

The Medical Register (1874) “1858 Dec 20, Richardson Benjamin Wills, 2 North Frederick street, Dublin, Lic 1844, Fell. 1844, R Coll Surg Irel”, page 427

The Medical Times and Gazette (1883) Obituary of Benjamin Wills Richardson, Vol. 1, page 516

Minutes of the Proceedings of the Dublin Microscopical Club (1873) Vol. 2, pages 241, 284, and 301-302

Power, John Hatch and B. Wills Richardson (1860) Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body: Descriptive and Surgical, with the Descriptive Anatomy of the Heart, Fannin & Co., Dublin

Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science (1876) “Exhibition of crystals of xanthine sulphate”, Vol. 16, pages 339-340

Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science (1880) “Section of Larynx of Human Foetus, exhibited”, Vol. 20, page 113

Report of the Seventh Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science (1837) “Annual Subscribers: Wills, Anthony, 17, Upper Gardiner St., Dublin”, page 43

Richardson, Benjamin Wills (1854) Percussor stethoscope, Dublin Journal of Medical Science, Vol. 18, pages 91-92

Richardson, Benjamin Wills (1856) Observations on fatty degeneration of the kidney and liver, Dublin Journal of Medical Science, Vol. 14, pages 309-337

Richardson, B. Wills (1862) Transparent carmine injections, Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science, Vol. 2, new series, page 118

Richardson, B. Wills (1866) Stops recommended for oblique illumination with the achromatic condenser, Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science, Vol. 6, new series, pages 10-12

Richardson, Benjamin Wills (1873) New bulbed stricture sound for exploring the urethra from behind forward, Dublin Journal of Medical Science, Vol. 56, pages 353-359

Richardson, Benjamin Wills (1873) On xanthine and some of its crystalline compounds, Minutes of the Proceedings of the Dublin Microscopical Club, Vol. 2, pages 229-230

Richardson, B. Wills (1877) White cement for final coating in microscopic mounting, Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science, Vol. 17, new series, page 101

Richardson, B. Wills (1880) Description of an India-rubber inhaler for ether anesthesia, The Retrospect of Medicine, Vol. 82, pages 327-328

Richardson, B. Wills (1881) On a blue and scarlet double stain, suitable for nerve and many other animal tissues, Journal of the Royal Microscopical Society, Vol. 1, series 2, page 573

Richardson, B. Wills (1881) Multiple staining of animal tissues with picro-carmine, iodine, and malachite-green dyes, and of vegetable tissues with atlas-scarlet, soluble blue iodine, and malachite-green dyes, Journal of the Royal Microscopical Society, Vol. 1, series 2, pages 868–872

Slater's National Commercial Directory of Ireland (1846) Dublin, Leinster, Barristers: “Wills Anthony, 17 Upper Gardiner st”, page 167

Surgical Lectures, Delivered in the Theatre of the Westminster Hospital (1880) “Amputation at the hip-joint … read by Mr. B. Wills Richardson, F.R.C.S.”, pages 106-108)

Transactions of the Microscopical Society of London (1867) “Quekett Microscopical Club, November 23rd … A box of slides from W. B. Richardson, Esq., F.R.C.S.I., of Dublin, as well as several donations from the members, were announced”, Vol. 15, page 91