Emmanuel Samuels, 1816 - 1886

by Brian Stevenson

last updated December, 2018

This American was a professional preparer of microscope slides from the mid 1850s until the late 1870s. Publications from both sides of the Atlantic mention his work, in particular his slides of diatomaceae. Samuels described himself in 1875, “my business is preparing microscopic specimens. (I) have been engaged in that work twenty years, and think that there is hardly a medical man in the United States but what has some of my specimens”.

Despite the number of Samuels’ slides that were spread across the U.S., they are now relatively scarce in collections and at auctions. This is often the case with Western Hemisphere slides of the 1800s, probably because they are boxed up in attics and basements, or thrown away, by people who do not recognize the collectability of these early pieces of history and art.

Figure 1.

Microscope slides by Emmanuel Samuels. The custom cover papers give his address in Milton, Massachusetts, where he lived until the early 1860s. Samuels moved to Boston in the mid-1860s, and later to Quincy. He is recorded as having produced slides from those places, although mounts with the addresses have yet to be located. The printed pattern used on these slides is very similar to that being used at the same time by Joseph Bourgogne of Paris.

Figure 2.

Magnified view of the printing on one of the ca. 1860 Samuels slides shown in Figure 1.

Figure 3.

An Emmanuel Samuels slide that was retailed by William Y. McAllister of Philadelphia.

Figure 4.

An undated photograph of Emmanuel Samuels, from a biographical note published in “The Condor”, 1928.

Emmanuel Samuels was born in Boston, Massachusetts in April, 1816. His father, Isaac, was an émigré from Poland, and his mother, Ruth, was a Bostonian. Emmanuel married Abigail Zanka in Boston on December 14, 1834. They had four children: three boys and a girl. The eldest son, Edward, became a noted naturalist and published the groundbreaking Birds of New England in 1870 (Figure 6). Daughter Adelaide became a celebrated novelist (Figure 7).

The Samuels moved to the nearby town of Milton, where they operated a farm. The 1850 census reported that Emmanuel was a “yeoman”, and employed two farm laborers. The farm appears to have been sold shortly afterward, as the 1855 census described Emmanuel’s occupation as “taxidermist”. He no longer employed laborers, although the family did have a domestic servant.

Emmanuel’s new profession was probably a major factor in a life-changing expedition. In December, 1855, he traveled to Sonoma County, California, to collect animals, eggs, plants, and other natural items for the Smithsonian Institute and the Boston Society of Natural History. A report to the Boston society stated, “Mr. Samuels reports that he arrived at Petaluma, California, December 1, 1855, and left, in consequence of ill health, on the 4th of July, 1856. He explored the country, and collected specimens, in the distance of twenty miles east, north, and west of Petaluma, being portions of the two counties of Sonoma and Marine (Marin county). He has sent to the Smithsonian Institution eleven large boxes, containing between 900 and 1000 species, and many thousand specimens”. The plants collected by Samuels were described by famed botanist Asa Gray. An 1857 report from the curators of the Boston Society of Natural History’s collections noted numerous specimens of insects, eggs, and preserved animals from Samuels’ trip to California.

Samuels made many other donations to the Boston Society of Natural History, including stuffed animals from Massachusetts. The first firm record of his making microscope slides was noted in the Society’s Proceedings in 1859, “Mr. E. Samuels presented a box containing twentyfour slides for the microscope, of specimens of diatoms from the intestines of echini from the Sandwich Islands, Port Jackson, New South Wales, Tortugas, and Florida, prepared and mounted by himself. The variety of diatoms thus obtained is very great, opening a vast field for the student in this department of Natural History; Mr. Samuels thought that fossil echinoderms in this way would yield many interesting fossil forms. The contents of the intestines thus far have been composed of about one half foraminifera, the residue of diatoms, spicules and gemmules of sponges, fragments of algae, and sand”. His later statements imply that Samuels had begun to seriously prepare microscope slides in about 1855.

Also in 1859, “Mr. Samuels presented a series of thirty microscopic slides, to be used for purposes of exchange with the London Microscopical Society”. Of these, Charles Stodder of the Boston Society reported, “The specimens he found to be very interesting, and some of them new; especially the diatoms from the intestines of holothurians and echini - collected for Prof. Agassiz and Mr. J. M. Barnard. Many species have been ascertained to be common to the Sandwich Islands and the Mediterranean; some are common to England, Nova Scotia, Boston Bay, and the Sandwich Islands; others are common to the Sandwich Islands, Zanzibar, and Florida,- in fact, diatoms have long been known as the most cosmopolitan of organisms. The new species, recognized as such, by Mr. A.M. Edwards, of New York, are Synedra magna, S. pacifica, Triceratium circulare (with three and four sides), T. elegans (with three and four sides), and T. undatum (with three, four, and five sides). These variations raise the question again, whether there is any distinction between Triceratium and Amphitetras; several four-sided species are described by Mr. Brightwell, and the only difference between T. wilkesii and A. wilkesii (Harvey & Bailey) is the number of sides. Among the rare and recently described forms are T. dubium (Bright.), Cocconeis jimbriata (Bright.), and Biddulphia reticulata (Roper). Campelodiscus striatus (Ehr.), figured by Brightwell in the Journal of the Microscopical Society, is abundant, but he is satisfied that it is distinct from Ehrenberg's species, answering neither to the description nor the original figure of that species; he proposes to call it C. brightwellii. Synedra undulata (Greg.) = Toxariumundulans (Bailey), and S. hennedyana (Greg.), and Naviculae, are abundant. Navicula didyma and N. lyra are abundant, showing great variations within the probable limits of each species. There are two forms of Ehrenberg's genus Actinocyclus, called by most English writers Eupodiscus; Stauroptera aspera (Ehr.) = Stauroneis pulchella (W.S.) is abundant and variable; in the Zanzibar slides he had seen an Auliscus which may be new, and an Isthmia certainly new, with many forms common also to the Sandwich Islands. Mr. Edwards has undertaken to describe and figure the new species, for publication in the Journal of the Society”.

The London Microscopical Society’s Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science carried Stodder’s report in 1861, “The diatoms of our coast have been but little studied. These specimens will, on that account alone, possess considerable interest, though they have only been glanced at, for want of time. Those from Quincy appear most promising. The Milton slide contains almost entirely what Mr. Samuels considers a new Himantidium. The Bangor and Bemis Lake deposits are similar to other ‘sub-peat’ deposits found all over New England, and described by Ehrenburg and Bailey. These have not been fully studied as yet. The diatoms from the intestines of Holothurians and Echini are of great interest. They were taken from animals collected for our members, Mr. Jas. M. Barnard and Professor L. Agassiz. Some of the slides, prepared and mounted by Mr. Samuels, coming into my possession last spring, I noticed that they were very rich in genera and species, and that many appeared to be new. I sent specimens to our corresponding member, Mr. A.M. Edwards, of New York, who has paid much attention to this department of science for several years. His interest was excited by the specimens, and a larger quantity of the material was procured from Mr. Samuels, and also some directly from Mr. Barnard, and cleaned by Mr. Edwards, which, although but partially investigated as yet, has yielded a rich harvest of new forms, as well as many but recently published in Europe, together with a great number of old and well-known species. The discovery of this source of supply of diatoms will yield important scientific results. We obtain specimens from localities otherwise all but inaccessible to the microscopist. We have ascertained that a great many species are common to the Sandwich Islands and to the Mediterranean; some species are found in the Sandwich Islands and the coasts, England, France, Nova Scotia, and Botany Bay; some common to Sandwich Islands, Zanzibar, and Florida. Diatoms have been long known as the most cosmopolitan of all organism. The information afforded by these slides adds very much to our former knowledge of this character. They seem to exist as species, almost independent of climate or locality. Mr. Edwards has undertaken to make a list of the Sandwich Island forms, and to figure and describe the new species, with the view to publication by our society. I have examined these slides, prepared by Mr. Samuels, and have registered, with ‘Bailey's indicator’, some of the new species of Mr. Edwards, as he has communicated them to me verbally or by letter, with his provisional names”.

The 1860 U.S. census recorded Samuels as “microscopist”, implying that slide-making was then his primary occupation. The family no longer employed a domestic servant, although that may have due to the children being teenagers, and 14 year-old daughter Adelaide assisting with household maintenance.

By 1865, the family had moved into the city of Boston. The 1865 Massachusetts census listed Emmanuel as being a “photographer”. The 1870 census stated that he “works on microscopes”.

1869 articles in The Proceedings of the Boston Society of Natural Science and The Monthly Microscopical Journal noted, “Mr. E. Samuels, in preparing a single specimen of Aulacodiscus oreganus, after placing it on the slide, found that it had divided, the upper shell slipping off from the under. This, he said, is the most perfect specimen of the division of this class of diatoms he had ever seen, and the most authentic, as the divisions really took place under the eye. This is a very interesting object, because it proves, if proof were needed, that these disks are formed of two shells, and thus conclusively reveals the fact that many species have been named by microscopists as new, that are only the thin under-layers of the shells of species already classified”.

Samuels served as an expert witness in an 1875 trial. The transcript reads, “Emmanuel Samuels sworn: Live in Quincy, and my business is preparing microscopic specimens; have been engaged in that work twenty years, and think that there is hardly a medical man in the United States but what has some of my specimens; without mechanical arrangements microscopes are not alike ; I have never seen two people who saw an object the same through a microscope; do not remember of ever having examined horse's blood, but have that of animals; have had no experience in examining blood”.

Samuels ceased commercial slide production during the 1870s. The 1880 census listed him as “retired”. He passed away on Jun 29, 1886, when 70 years old.

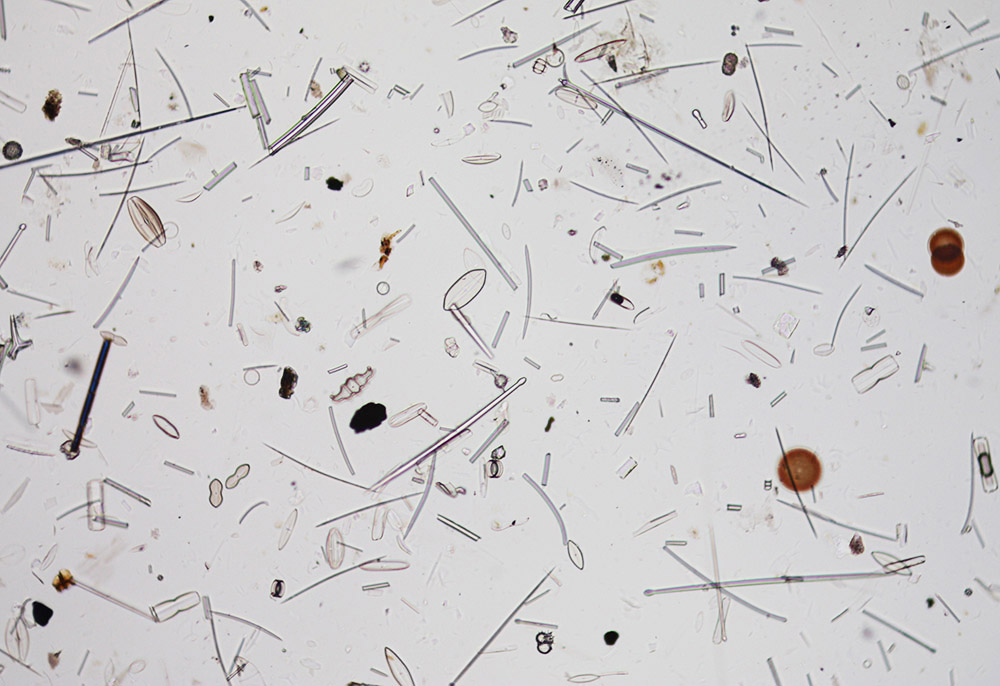

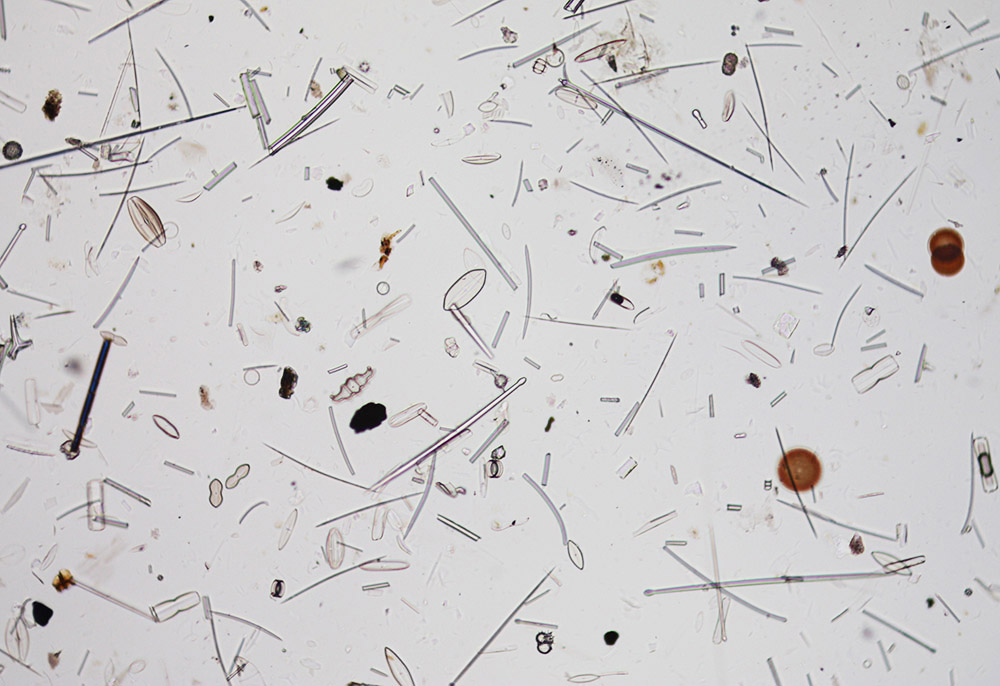

Figure 5.

Diatoms from Zanzibar, prepared by Emmanuel Samuels. Photographed with a 10x objective lens and a C-mounted digital SLR camera.

Figure 6.

Title page of Edward Samuels’ 1870 “The Birds of New England”, which had a significant impact on ornithology.

Figure 7.

Title page of one of Adelaide Samuels’ “Dick and Daisy” series of novels (1874).

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Howard Lynk for sharing images of a slide from his collection.

Resources

Bouvé, Thomas Tracy (1880) Historical Sketch of the Boston Society of Natural History, page 71

The Condor (1919) Emmanuel Samuels, Vol. 21, pages 106-107

Death record of Emmanuel Samuels, accessed through ancestry.com

Forest and Stream (1908) Obituary of Edward A. Samuels, Vol. 70, page 935

Gray, Asa (1856) List of plants collected by Emanuel Samuels, in Sonoma County, California, in 1856, Proceedings of the Boston Society of Natural History, pages 141-145

Kitton, F. (1878) Hyalodiscus Subtilis and H. Californicus, The American Journal of Microscopy and Popular Science, Vol. 3, pages 247-250

The Monthly Microscopical Journal (1869) The double plate of Aulacodiscus oreganus, page 326

Palmer, T.S. (1928) Notes on persons whose names appear in the nomenclature of California birds: “Samuels, Emanuel. Born in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1816; died in 1886. Father of Edward Augustus Samuels (1836-1908), who was well known as the author of the "Birds of New England." In 1855, Emanuel Samuels was sent to California to collect for the Smithsonian Institution, the Boston Society of Natural History and the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. Much of his was done near Petaluma, Sonoma County, where he secured the type of the sparrow (Melospiza m. samuelis) which now bears his name”, The Condor, Vol. 30, pages 261-307

Proceedings of the Boston Society of Natural History (1857) Notes on Emmanuel Samuels’ expedition to California and of his contributions to the Society’s collections, Vol. 6, pages 38-39, 145-154, 171, 219, 312, and 388

Proceedings of the Boston Society of Natural History (1859) Vol. 7, pages 136-137, 142-150, 156, 161, 184-185, and 205

Samuels, Adelaide F. (1874) Adrift in the World, or Dick and Daisy’s Early Days, Lee and Shepard, Boston, and numerous other works of fiction

Samuels, Edward A. (1870) The Birds of New England, Noyes, Holmes, and Company, Boston

Stodder, Charles (1861) Report on slides of Diatomaceae, mounted by E. Samuels, for Boston (U. S.) Society Of Natural History, and presented to the Microscopical Society Of London, Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science, pages 25-28

U.S. and Massachusetts censuses, accessed through ancestry.com

Warren, R.S. (1882) The preparation of diatoms, The American Monthly Microscopical Journal, Vol. 3, pages 111-115

Wharton, Francis (1875) Wharton and Stille's Medical Jurisprudence, Vol. 2, Part 2, pages 702-703