Figure 1. Microscope slides prepared by Frank P. Smith. Some are dated, ranging between 1899 and 1901. 15 Cloudesley Place, Islington, was his childhood home, where he lived until he married in 1907.

Frank Percy Smith, 1880 - 1945

by Brian Stevenson

last updated August, 2018

Frank Smith’s curious and inventive mind led him in directions that he probably never imagined as a child. Stuck in a boring government office job, Smith found an outlet in studying nature, and taught himself to be a renowned expert in spiders. He undertook microscopical investigations of his subjects, and became an expert slide-maker. He exchanged slides with numerous other enthusiasts throughout the world. This interest led him to join the Quekett Microscopical Club. He edited the QMC’s Journal for six years. For extra money, Smith presented talks on scientific topics, using lantern slides from his own macroscopic and microscopic photographs. In 1908, film-maker Charles Urban provided Smith with a motion picture camera, which he used to make close-up films of flies performing amusing feats such as spinning balls or sticks with their feet. A career in film-making followed, producing additional films of magnified insects and spiders. He is probably most famous for his time-lapse films of flower buds opening and plant shoots growing; Smith was the first person to exhibit that type of motion picture.

Figure 1.

Microscope slides prepared by Frank P. Smith. Some are dated, ranging between 1899 and 1901. 15 Cloudesley Place, Islington, was his childhood home, where he lived until he married in 1907.

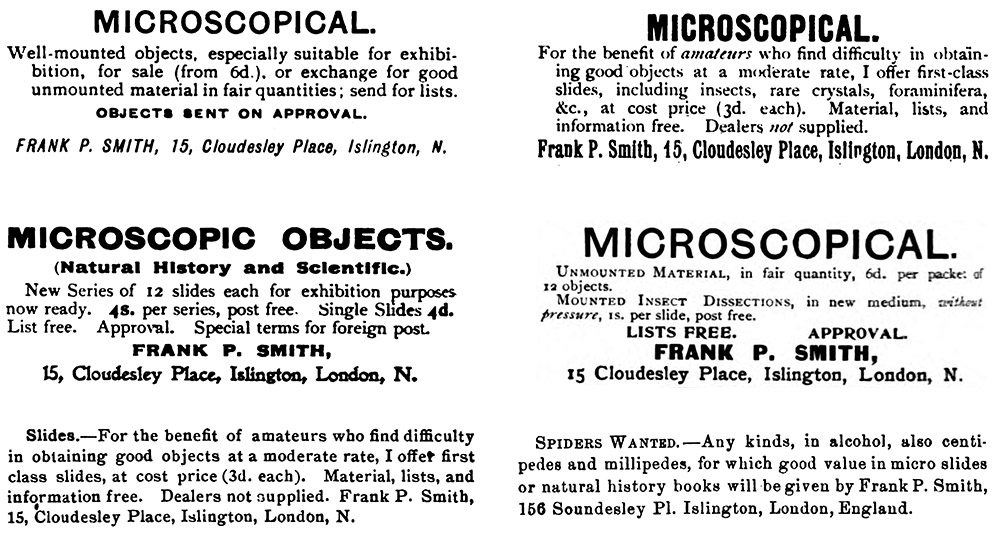

Figure 2.

Advertisements for Frank Smith’s microscope slides, 1898-1900. The top four are from “Science-Gossip” (published in London, England), and the lower two are from “The American Monthly Microscopical Journal”.

Figure 3.

Frank Percy Smith.

Frank Percy Smith was born on January 12, 1880, in Islington, London, son of Frank David and Ada Smith. The father worked as a painter and a printer. One of Frank P. Smith’s childhood friends was Charles R. Percival, who also became a noted microscope slide-maker.

Young Frank went to work at age fourteen, as a clerk with the Board of Education. By all accounts, this was a tedious and boring job for him. Nature studies provided a relief. He eventually focused on studying spiders, a relatively unexplored aspect of biology. By 1898, Smith had become proficient enough in preparing microscope slides that he was advertising them for exchange as “well-mounted objects” (Figure 2).

Smith joined the Quekett Microscopical Club on March 17, 1899, not long after his nineteenth birthday.

In addition to spiders, Smith collected and prepared a variety of arthropods and other subjects (Figure 1). As an example, two notes from him were published in 1900, “With the approach of the holiday season some of our readers who are thinking of visiting Margate may be grateful to Mr. Frank P. Smith for reminding them that the smooth sand surrounding the extremity of the Nayland Rock breakwater is a good locality for collecting foraminifera. … Mr. Smith also recommends Epping Forest as a good locality for the beautiful diamond beetles found in every cabinet of microscopic objects. They may be picked from the trunks of trees, or collected by simply sweeping a net amongst the nettles and low herbage. Mr. Smith recommends that the beetles should be dried for some weeks before mounting whole, and suggests that a cyanide bottle only should be used for a killer, as spirit has a tendency to destroy the colour”.

Smith published a five-part series, “An introduction to British spiders” in Science-Gossip during 1900. In conjunction, the magazine published these notes: “In view of the series of articles on British Spiders now appearing in Science-gossip, the Editor appeals to Field Naturalists to save and send to the author, Mr. Frank P. Smith, 15, Cloudesley Place, Islington. N., any specimens they may meet with. Mr. Smith will make the best return possible for the material. Full instructions for collecting Spiders appear in this number on page 195. … A few words on the collection and preservation of specimens may be useful. The apparatus required for the collection of spiders depends to a great extent on the collector's fancy. It need not be extensive. A few bottles of spirit, some tubes, about 3/4 in. in diameter, and a pair of forceps, are all that are necessary. A piece of waterproof cloth to kneel upon, when working in moist localities, is a useful precaution against taking cold. A well-known writer wisely advocates the use of a piece of string connecting the cork with the bottle, to obviate the loss of time spent in searching for the cork, when one should be looking for spiders. These animals seem to exercise a vast amount of ingenuity in evading the bottle of the would-be captor, and, consequently, their methods of escape should be carefully noted. The species which run rapidly upon the ground may, after a little practice, be hunted by the right hand into a tube held by the left. If convenient, a few live specimens should be kept in a vivarium at home, and their habits watched. Young specimens of rarities may be reared to maturity in this way. In winter and spring spiders are best searched for amongst grass, dead herbage, under pieces of wood, and branches of trees that have lain undisturbed for some time. Turning stones also repays the trouble towards the approach of warm weather. In summer, sweeping grass, rank herbage, and rushes with a strong net, obtains multitudes of specimens. Shaking bushes over an inverted umbrella is productive. The same plan in autumn secures the larger web-spinners. The Thomisidae may be often found resting in composite flowers, where they await their prey”.

Frank Smith joined the Essex Field Club on December 14, 1901. The previous year, “Mr. F.P. Smith made some observations on the mode of occurrence of Spiders, and the methods to be employed in their collection and preservation”, and “Mr. F.P. Smith and Mr. Pickard-Cambridge subsequently furnished the Editor with lists of the species observed. These have been combined by Mr. Cambridge in the Report printed in the present part of the Essex Naturalist”.

Smith became Editor of the Journal of the Quekett Microscopical Club in 1904 (Figure 4). He performed that service until 1910. Over the years, Smith published numerous papers in the Journal, and gave many talks to the QMC, primarily on spider biology. Among these was description of a spider “with a form which appears to me to be new to science”, which he named after its captor, another spider enthusiast and avid microscope slide-maker, Richard Hancock.

During the early 1900s, Smith began presenting public lectures. A 1904 lecture in Hampstead was described, “At the Subscription Library, Prince Arthur Road, N.W., on February 29 last, Mr. Frank P. Smith delivered a lecture entitled ‘Spiders - their Structure and Habits’, to a full and appreciative audience of members and their friends. He showed how in some instances the female, when she had no longer any use for him, devoured the male, who would reappear in the shape of eggs or web. Mr. Smith said he would be merciful to his auditors and not pelt them with the forbidding names that are used in spider-study, though to give an idea of what they were like he had some of them thrown upon the screen. The slides used were superb, and were all of Mr. Smith's own preparation”.

In preparation of such talks, Smith painted a series of white-on-black illustrations for use as negatives to produce lantern slides. A number of these large (ca. 10 x 10 inches / 25 x 25 cm) artworks have survived (Figure 5).

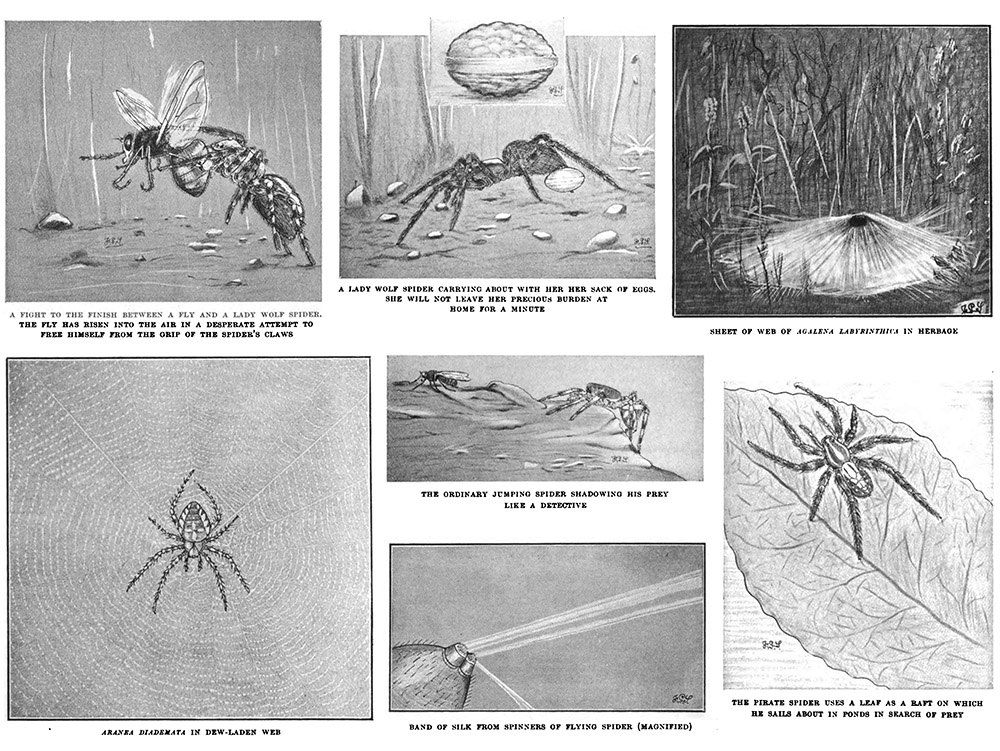

Smith also commercially produced illustrations for magazines and books (Figure 6 and 7).

Frank married in 1907, to Kate Louise Ustonson.

Around this time, Smith began working with Charles Urban’s exhibition company. One story holds that Urban saw a photograph by Smith of a blowfly feeding on a drop of sugar, whereupon Urban asked Smith if he could make a moving picture of that scene. That led to Smith being given access to motion picture equipment, and the start of a new career.

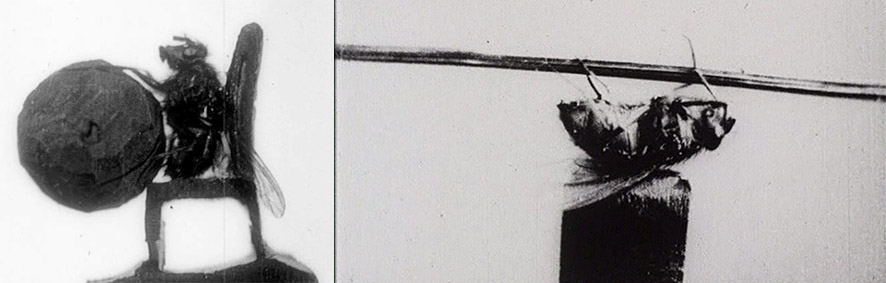

Smith’s first public film presentation occurred in September or October, 1908, at London’s Palace Theatre. It included footage of flies fastened to “chairs” and other objects, while manipulating small balls, sticks, and other objects with their feet (Figure 8, and links at the end of this essay). The initial reaction from reviewers was that Smith’s film was fakery. This was probably influenced by his presentation at the Palace, which was a venue where trick shows were often presented.

He took a different tack, and, on November 11, 1908, presented the Royal Photographic Society with “Flies and their foes, through microscope and camera”. His talk included fly anatomy and life-cycles, and information on predators such as spiders, geckos, and frogs, “Mr. Smith’s lecture was illustrated by a number of lantern slides, microscopic and otherwise, and concluded with a cinematograph display, for which, he said, he had to thank the Charles Urban Trading Company. Hearing he was lecturing that evening, Mr. Charles Urban had kindly sent down a cinematograph apparatus, the records for which had been prepared from his (Mr. Smith’s) negatives. The records illustrated the wonderful strength and endurance of the blue-bottle, and also the results of an attempt to ‘train’ the insects to use miniature dumb-bells and perform acrobatic feats. Another film brought home the objectionable habit of the fly of feeding on putrid matter, while others, again, illustrated the characteristic action of the fly's trunk, the preparations for spinning made by the baby spiders, an attack by a large spider upon a fly of almost equal strength, as well as the antics of the lizard and the green tree-frog”. At the end, the Society’s Chairman “said that the lecturer had brought to the aid of some of the best natural history pictures ever shown a rich fund of humour and a gift of oratory quite unusual in lantern lectures, (and) proposed a vote of thanks to him and to the Charles Urban Trading Company, who had gone to so much trouble in providing the cinematograph apparatus. The vote of thanks was passed with acclamation”.

The Birth of a Flower, Smith’s series of time-lapse shots of blooming films of roses, tulips, and other flowers, was a major hit of 1910. He then resigned from the Board of Education to become a full-time film-maker. Frank and his wife moved to a more spacious house in semi-rural Southgate, in northern London

During the Great War, Smith served as a photographer in the Royal Navy. He produced aerial films of battlefields, and animated maps of movements.

After the war, Smith returned to commercial film-making.

While Smith remained a member of the Quekett Microscopical Club for the remainder of his life, his enthusiasm for spiders faded. His spider collection came into the possession of Richard Hancock. W.S. Bristow wrote that Hancock, “offered to sell me F.P. Smith’s collection of spiders, microscopes and lantern slides for £100 in 1928”.

Frank Smith died on March 24, 1945, an apparent suicide.

Figure 4.

Title page of an issue of the “Journal of the Quekett Microscopical Club”, 1904, edited by Frank P. Smith. He served as editor from 1904 until 1910.

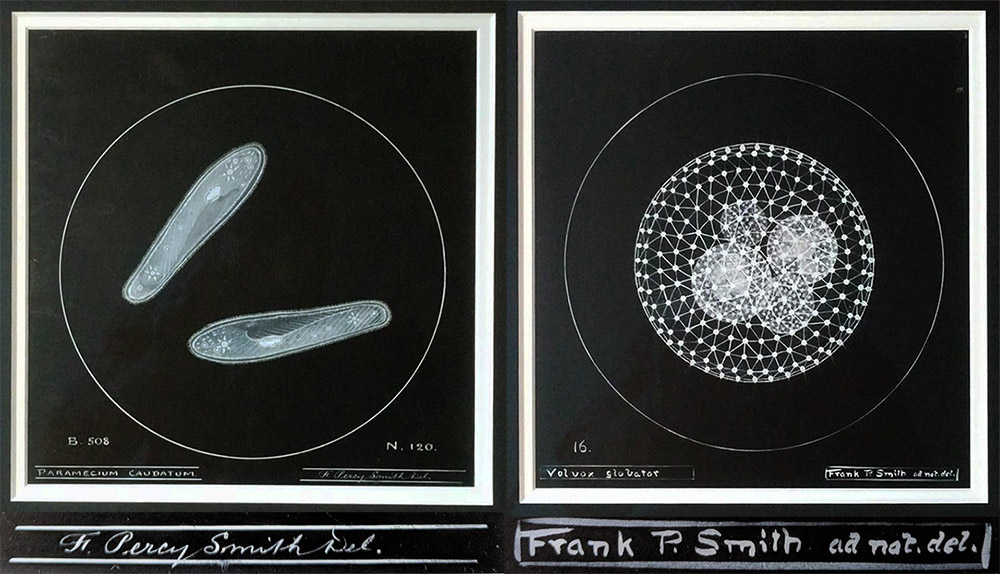

Figure 5.

White-on-black paintings by Frank P. Smith, for use as negatives in preparing lantern slides for his talks.

Figure 6.

Illustrations by F.P. Smith for “The Leisure Hour”, 1904.

Figure 7.

A 1907 advertisement for a book that was illustrated by Frank P. Smith.

Figure 8.

Two stills from Frank Smith’s “The Acrobatic Fly”, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8hlocZhNc0M.

Figure 9.

Smith filming in his garden in Southgate.

Figure 10.

Smith filming a flower bud.

Resources

American Monthly Microscopical Journal (1900) Advertisements from F.P. Smith, Vol. 21, pages 32 and 236

Bracegirdle, Brian (1998) Microscopical Mounts and Mounters, Quekett Microscopical Club, London, pages 86 and 170, Plates 33-K and 33-L

Bristowe, William S. (1973) Anecdotal notes about our British predecessors, “Hancock was a plumpish auctioneer from Birmingham who was less a naturalist than a collector of many things varying from Japanese sword hilts to natural history objects. He offered to sell me F.P. Smith’s collection of spiders, microscopes and lantern slides for £100 in 1928. Ultimately he bequeathed all his collections, I believe, to a Birmingham Museum”, Bulletin of the British Arachnological Society, Vol. 2, pages 193-200

Burgess, M. (1993) F.P. Smith and the secrets of nature, Quekett Journal of Microscopy, Vol. 37, pages 146-160, 234-243, and 330-343

The Essex Naturalist (1900) Minutes of the October 6 meeting, page 294

The Essex Naturalist (1901) Minutes of the December 14 meeting

England census and other records, accessed through ancestry.com

Gaycken, Oliver (2013) “The Living Picture”: On the circulation of microscope-slide knowledge in 1903, History and Philosophy of the Life Science, Vol. 35, pages 319-339

Gaycken, Oliver (2015) Devices of Curiosity, Oxford University Press, Oxford

Journal of the Quekett Microscopical Club (1910) Minutes of the February 22 meeting, “Reference was made to the much-appreciated services of Mr. F.P. Smith, for six years Hon. Editor of the Journal, and a special vote of thanks was passed by acclamation at the announcement of his resignation of that office”, Series 2, Vol. 10, page 45

Journal of the Quekett Microscopical Club (1914) Members: “Smith, Frank P., 2, King’s Villas, Chase Road, Southgate”, Series 2, Vol. 12

Journal of the Quekett Microscopical Club (1927) Members: “Smith, Frank P., 2, King’s Villas, Chase Road, Southgate, N.14”, Series 2, Vol. 15

Journal of the Quekett Microscopical Club (1939) Members: “Smith, Frank P., 2, King’s Villas, Chase Road, Southgate, N.14”, Series 4, Vol. 1

Journal of the Royal Microscopical Society (1906) Report of the November 16 meeting of the Quekett Microscopical Club, “Mr. F.P. Smith communicated a paper on "The British Spiders of the genus Lycosa." Mr. F.P. Smith delivered a lecture on ‘Vagabond Spiders’. He said that by ‘vagabond’ he meant ‘wandering’, and included in the term all those spiders which did not make snares. The three principal groups of ‘vagabonds’ were represented by the families Lycosidae, Thomisidae, and Salticidae, and their characteristics were described at some length”, pages 106-107

Nature Notes (1905) Advertisement for Neolithic Man in North-East Surrey, illustrated by Frank Percy Smith, Vol. 16, page iv

The Photographic Journal (1908) Report on Smith’s presentation to the Royal Photographic Society, Volume 32

Science-Gossip (1898) Advertisements from F.P. Smith, Series 2, Vol. 4, beginning with the November issue

Science-Gossip (1899) Advertisements from F.P. Smith, Series 2, Vol. 5, numerous issues

Science-Gossip (1900) Foraminifera from Kent, Series 2, Vol. 5, page 87

Science-Gossip (1900) Diamond beetles, Series 2, Vol. 5, page 87

Science-Gossip (1900) Spiders wanted, Series 2, Vol. 5, page 224

The Selborne Magazine (1904) Report on F.P. Smith’s lecture in Hampstead, Vol. 15, page 77

Smith Frank P. (1900) An introduction to British spiders, Science-Gossip, Series 2, Vol. 5, pages 193-195, 239-240, 308-310, 328-330, and 360

Smith Frank P. (1904) The spiders of the sub-family Erigoninae, Journal of the Quekett Microscopical Club, Series 2, Vol. 9, page 9

Smith Frank P. (1904) The spiders of the Erigone group, Journal of the Quekett Microscopical Club, Series 2, Vol. 9, page 109

Smith Frank P. (1904) The spiders of Epping Forest, The Essex Naturalist, Vol. 13, page 49

Smith Frank P. (1905) The spiders of the Walckenaëria group, Journal of the Quekett Microscopical Club, Series 2, Vol. 9, page 239

Smith Frank P. (1905) Anglia hancockii, a spider new to science, Journal of the Quekett Microscopical Club, Series 2, Vol. 9, pages 247-248

Smith Frank P. (1906) The spiders of the Diplocephalus group, Journal of the Quekett Microscopical Club, Series 2, Vol. 9, page 295

Smith Frank P. (1906) The literature of the sub-family Erigoninae, Journal of the Quekett Microscopical Club, Series 2, Vol. 9, pages 321-326

Smith Frank P. (1908) Some British Spiders Taken in 1908, Journal of the Quekett Microscopical Club, Series 2, Vol. 10, pages 311-334

Smith Frank P. (1909) Note on the mounting of spider dissections as microscopical objects, Journal of the Quekett Microscopical Club, Series 2, Vol. 10, page 473

Spitta, Edmund J. (1907) “Mr. F.P. Smith, Hon. Editor to the Quekett Microscopical Club, writes: ‘I usually use a 2-in., 1-in., and 2/3rds for ordinary spider work, employing a 1/4-in. for detailed examinations. By far the best way to examine a spider is to put it into a pomade-pot lid, cover it with methylated spirit, and treat it as an opaque object, using of course low powers. If suitable for preservation it can be subsequently mounted and used as a transparency, when I employ the 1/4-in’ ”, in Microscopy: The Construction, Theory and Use of the Microscope, E.P. Dutton & Co., New York, page 326

Stevens, Frank (1904) By-paths in nature, with illustrations by Frank Percy Smith, The Leisure Hour

Suttie, Boyd (2000) C.R. Percival: the work and equipment of a professional slide preparer, Rittenhouse, Vol. 14, pages 77-94

Web links to some of F.P. Smith’s film work:

McRobbie, Linda Rodriquez (2017) The Shy Edwardian Filmmaker Who Showed Nature’s Secrets to the World: F. Percy Smith made flies dance, ants battle, and flowers bloom, https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/f-percy-smith-nature-films

The Acrobatic Fly (1910) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8hlocZhNc0M

The Birth Of A Flower (1910) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C5eAEXKJRmA

Many other examples of Smith’s work can be found by searching “Percy Smith”