Francis Watkins, 1723 - 1791

Addison Smith, 1737 - 1795

Jeremiah Watkins, 1758 - 1810

Walter Watkins, 1759 - 1798

William Hill, ca. 1775 - 1847

Francis Watkins, Jr., 1796 - 1847

Mary Ann Hitchcock Watkins, 1803 - after 1856

Abraham Harrison Day, ca. 1822 - after 1856

businesses:

Francis Watkins, 1747 - 1784 (possibly 1791)

Watkins and Smith, 1763 - ca. 1774

J. & W. Watkins, 1784 (possibly began as late as 1791) - ca. 1798

J. Watkins, ca. 1798 - ca 1818

Watkins and Hill, ca 1818 - 1856

by Brian Stevenson

last updated November, 2021

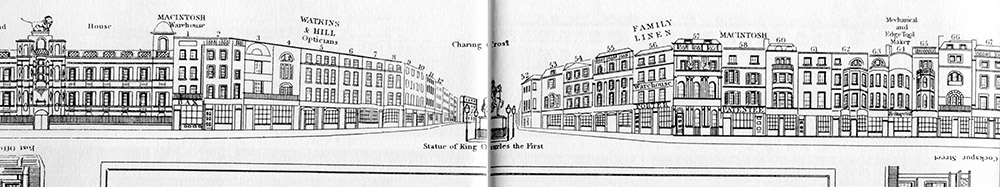

The Watkins optical business, under several iterations, operated for nearly 110 years from a shop at 5 Charing Cross, London. It was begun in 1747 by Francis Watkins. In 1763, Watkins also formed a partnership to help his son-in-law and former apprentice, Addison Smith, who had opened a shop in The Strand. Watkins retired in 1784 and passed his Charing Cross business to his nephews Jeremiah and Walter. It later passed to Jeremiah's son, Francis Jr., who partnered with his father's foreman, William Hill, as Watkins & Hill. Both of those men died within a month or so of each other, whereupon Watkins & Hill was maintained for another nine years by Francis' widow, Mary Ann, and manager Abraham Day. The business was sold to Elliott Brothers in 1856.

Francis Watkins is particularly notable for introducing the concept of a hinged joint in the microscope limb, so that it can be inclined to a comfortable angle. His microscope designs are very distinct from those of other makers. Later microscopes from Watkins / Watkins & Hill generally followed the standard patterns of their times, and it is likely that some/all were brought in from wholesale manufacturers.

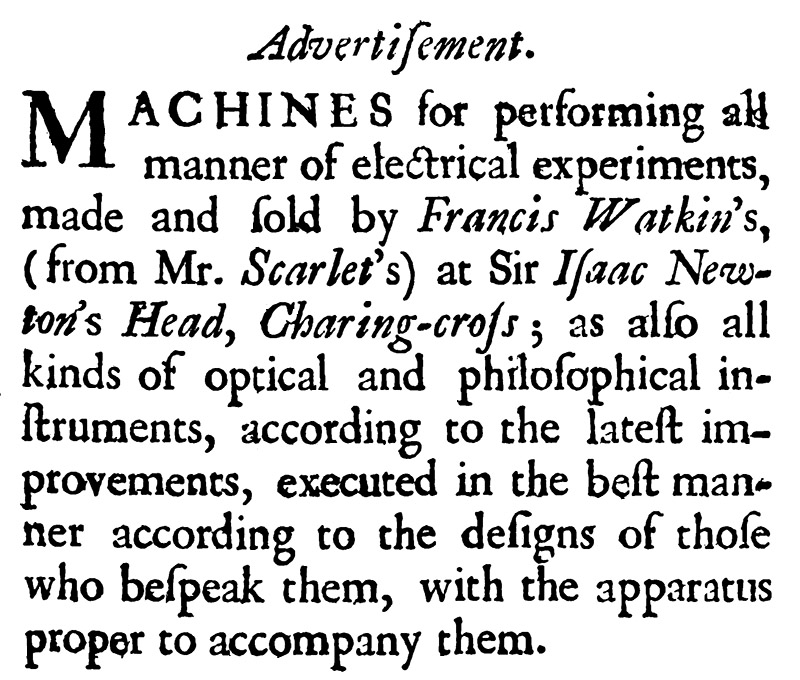

The Watkins lineage produced a wide variety of scientific and engineering apparatus, including a range of early electrical equipment. Francis Watkins advertised his shop with a sign that showed "Isaac Newton's head", an indication that he sold a range of scientific items. In contrast, an optician who primarily dealt in eyeglasses would more likely have a sign that prominently featured spectacles.

Additionally, Francis Watkins played important roles in development and retailing of achromatic telescopes. Watkins was relatively wealthy, due to substantial real estate investments, and fronted the money that was necessary for John Dollond to pay for the patent on his achromatic telescope design. Later, as Master of the Spectaclemakers' guild and as a retailer, Watkins was deeply involved in lawsuits related to the Dollond's patent. Further details are provided below.

Figure 1.

Three ca. 1750s microscopes by Francis Watkins, set up as simple and compound instruments. The lens mounts are signed "F. Watkins, London". Images adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from http://www.mhs.ox.ac.uk/object/inv/47695 and internet auction sites.

Figure 2.

A ca. 1750s silver microscope compendium by Francis Watkins. The compound microscope is signed "Fra Watkins London" and the solar microscope is signed "Fra Watkins Charing Cross London". Image adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from http://www.mhs.ox.ac.uk/object/inv/53619.

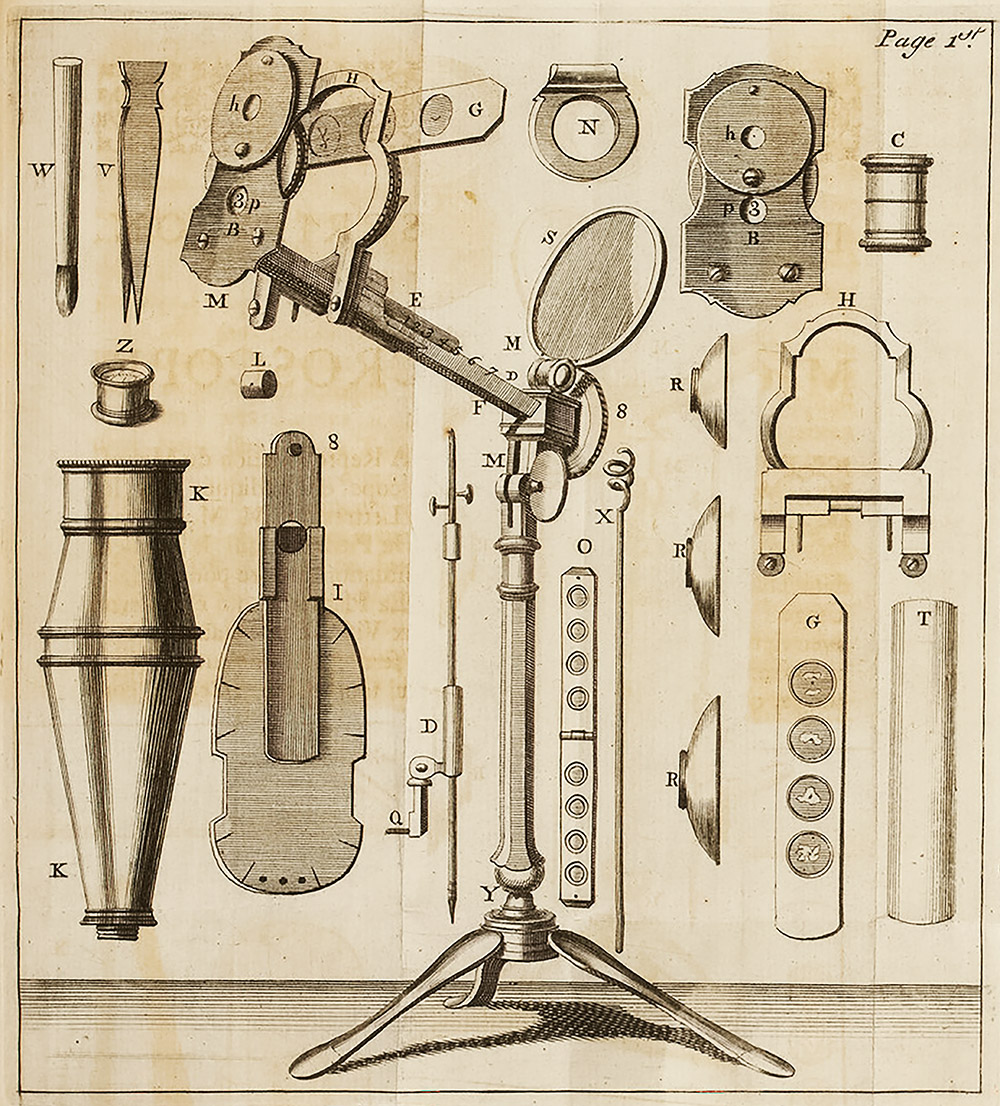

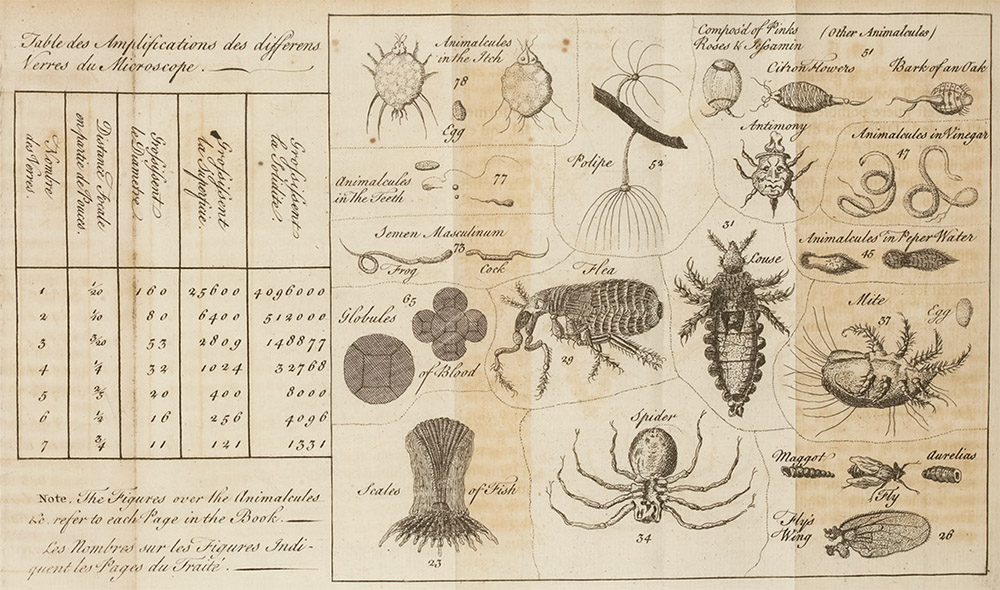

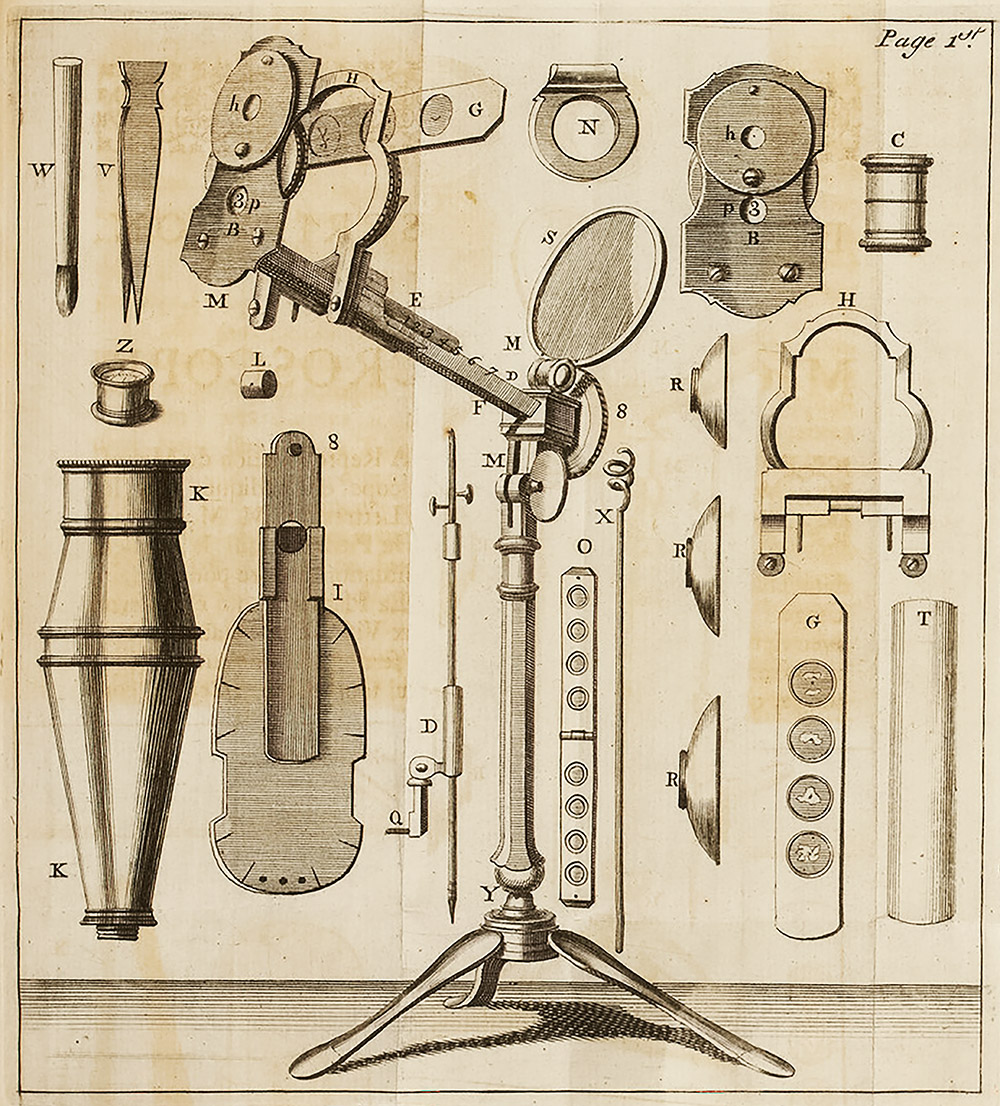

Figure 3.

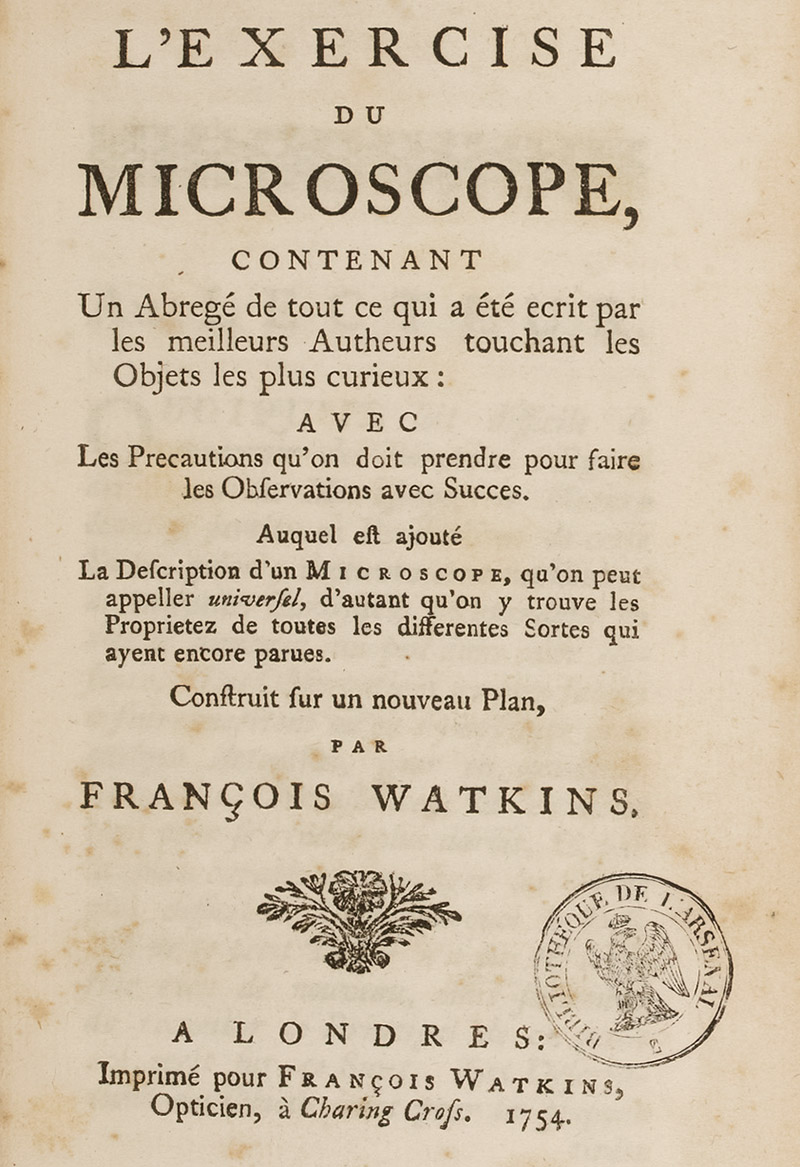

An illustration of Francis Watkins' compound/simple microscope, from his 1754 "L' Exercise du Microscope".

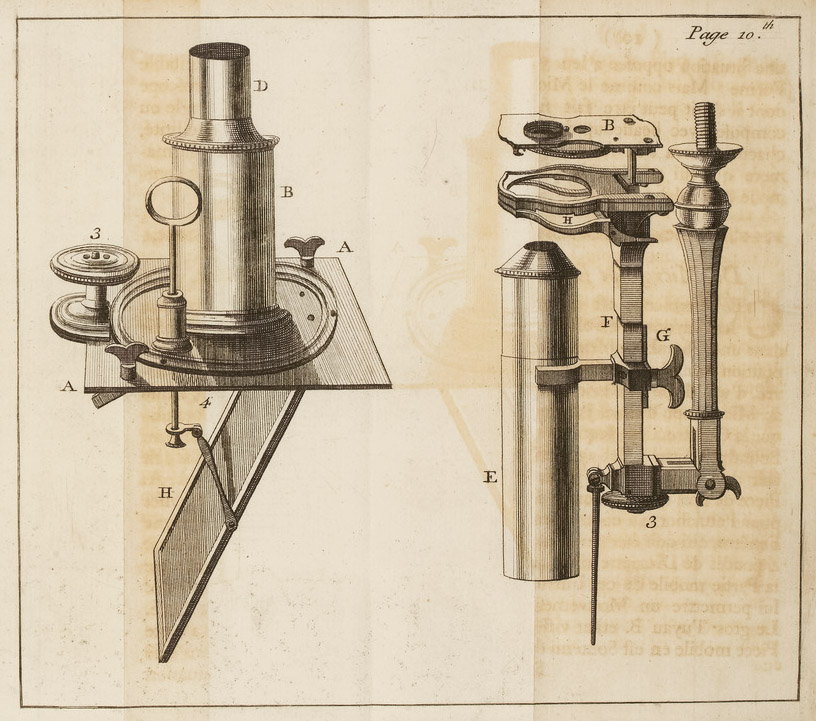

Figure 4.

Illustrations of Francis Watkins' solar and small compound/simple microscopes, also from his 1754 "L' Exercise du Microscope".

Figure 5.

Two ca. 1754 small simple/compound microscope by Francis Watkins. They could be screwed into a circular base, as seen in the left image, or held in the hand. The stages are removable, and attach to the instruments via a pair of prongs that fit into holes. Images adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co8421/smallest-pocket-microscope-by-watkins-with-access and https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co8000/simple-microscope-1747-1784-simple-microscope.

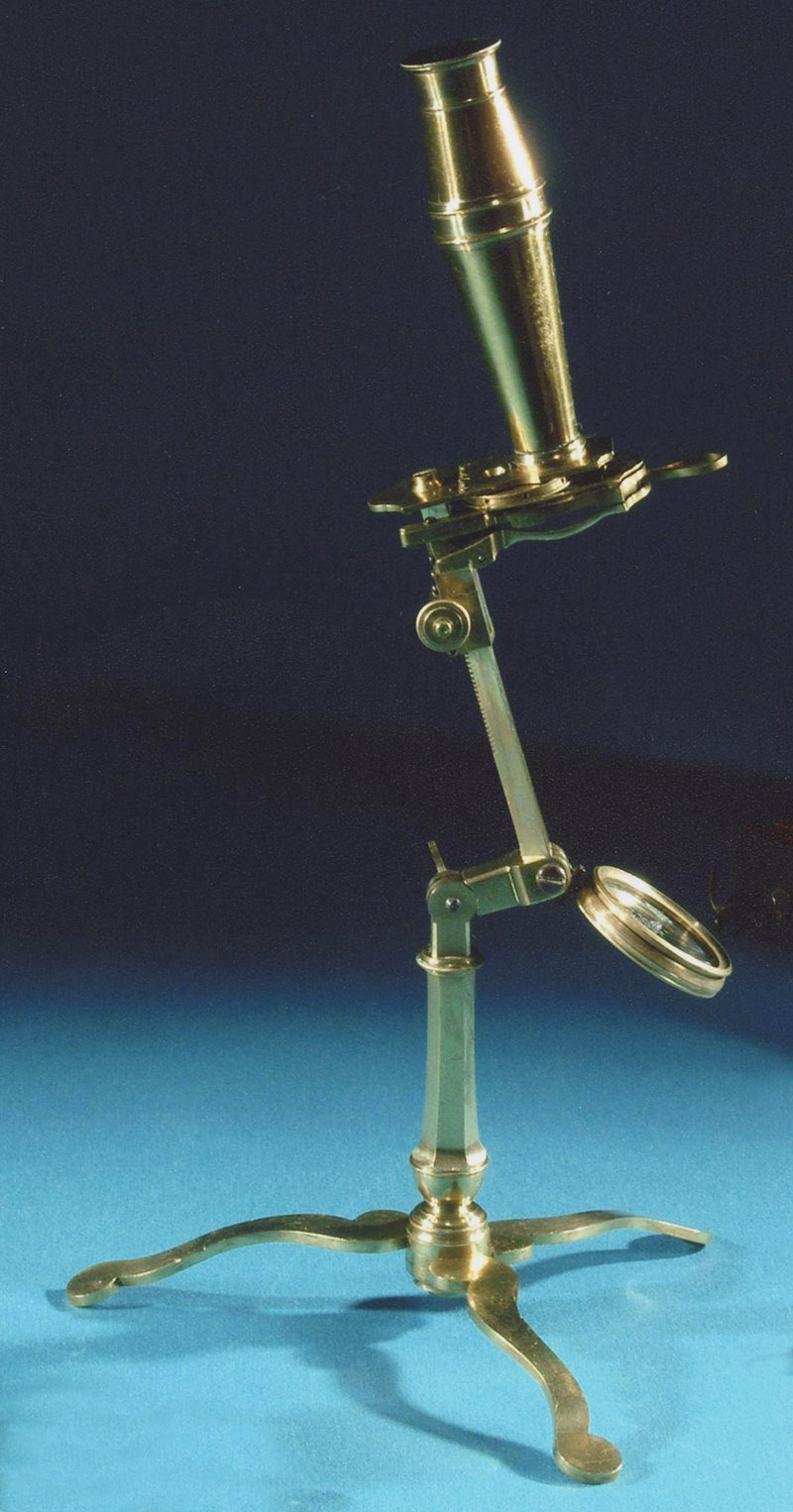

Figure 6.

A Cuff-type microscope, signed by Francis Watkins. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet sale site.

Figure 7.

A ca. 1770s Watkins-type microscope, signed "Smith London" (i.e. produced by Addison Smith). Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Figure 8.

Two ca. 1770 microscope compendia, both signed by Watkins and Smith. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co8127/optical-cabinet-by-watkins-and-smith-in-fish-skin and https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co8114/optical-cabinet-optical-instruments.

Figure 9.

A ca. 1790s solar microscope, engraved "J. and W. Watkins". Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/solar-microscope/HwEGR0qmDKGmnA.

Figure 9B.

Monocular opera glass, signed "Watkins, Charing Cross". The absence of a first initial suggests production after the death of Jeremiah Watkins (1810), when young Francis Watkins was supervised by his mother, and before the formation of Watkins and Hill (1817). Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

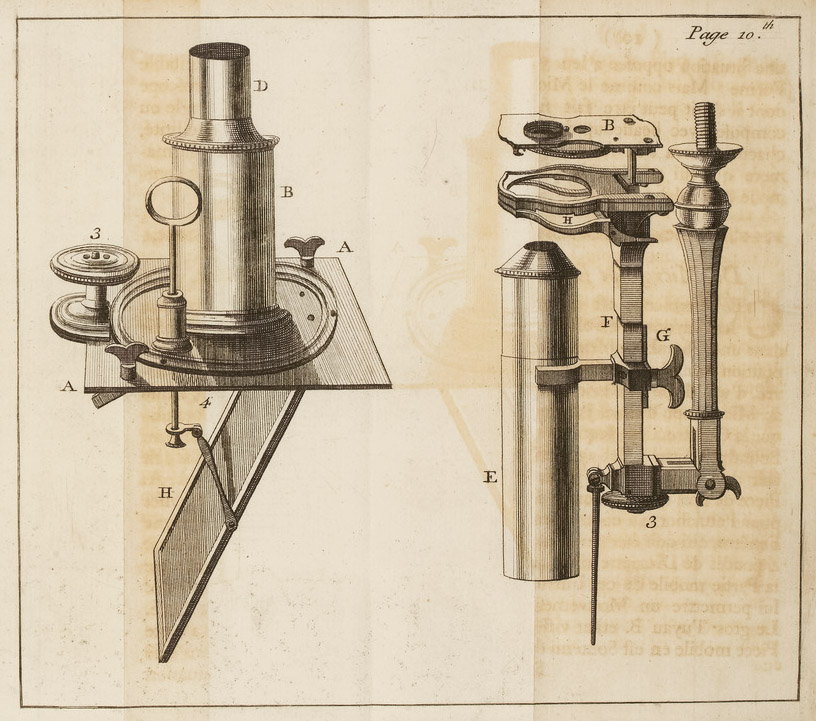

Figure 10.

A ca. 1820 microscope by Watkins and Hill. It is the form generally known as "Jones' Most Improved". Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

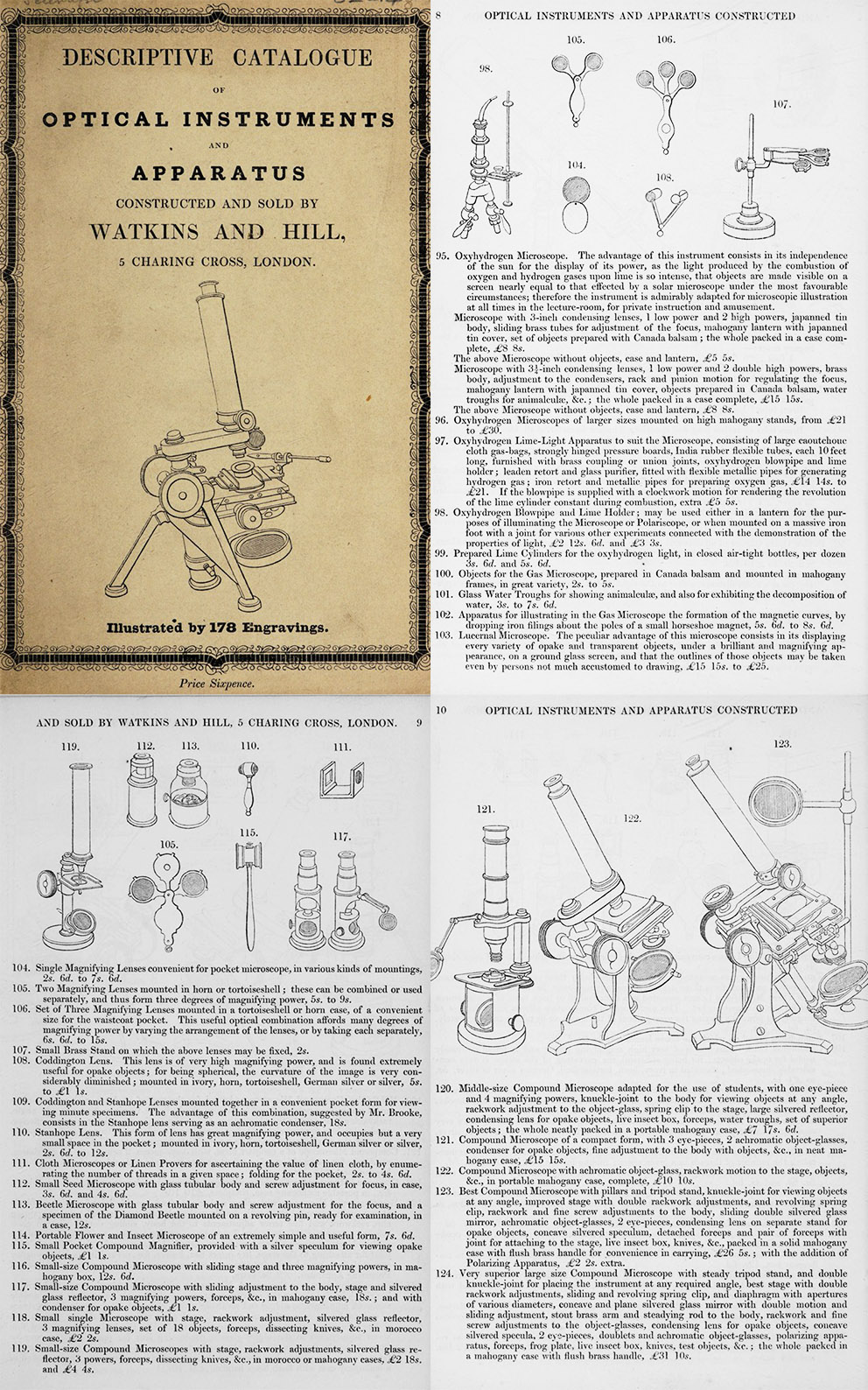

Figure 11.

A ca. 1830 microscope by Watkins and Hill. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Figure 12.

Ca. 1830 microscope by Watkins and Hill. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Figure 13A.

A ca. 1830-40 microscope by Watkins and Hill. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Figure 13B.

A ca. 1840 microscope, unsigned but it has a Watkins and Hill trade label inside the cabinet. Adapted by permission from https://www.facebook.com/scopeporn/posts/745283752573427.

Figure 13C.

ca. 1840s microscope, engraved on the foot, "Watkins and Hill, Charing Cross, London". Adapted by permission of Jurriaan de Groot.

Figure 13D.

Illustration of a Watkins and Hill "Small-size compound microscope with stage, rackwork adjustments" from their ca. 1850 catalogue (see Figure 14), and two surviving examples. Both are marked "Watkins and Hill, Charing Cross, London". An example is known that was retailed by Robert B. Bate, whose business closed in 1850, implying that this form was produced during the 1840s. The same model was also manufactured and sold by Elliott Brothers, who acquired the Watkins & Hill business in 1856. Images of microscopes adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from internet sale sites.

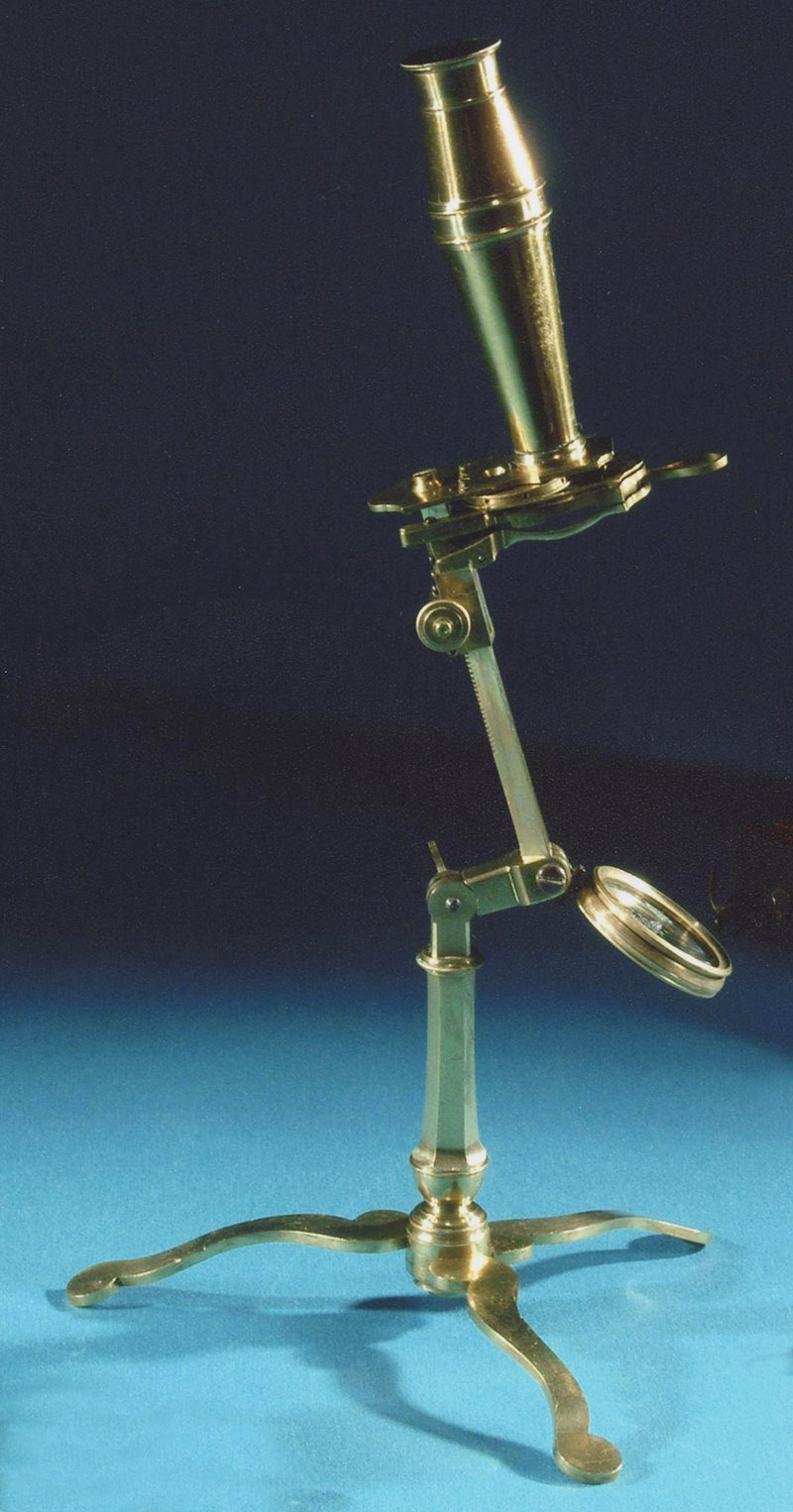

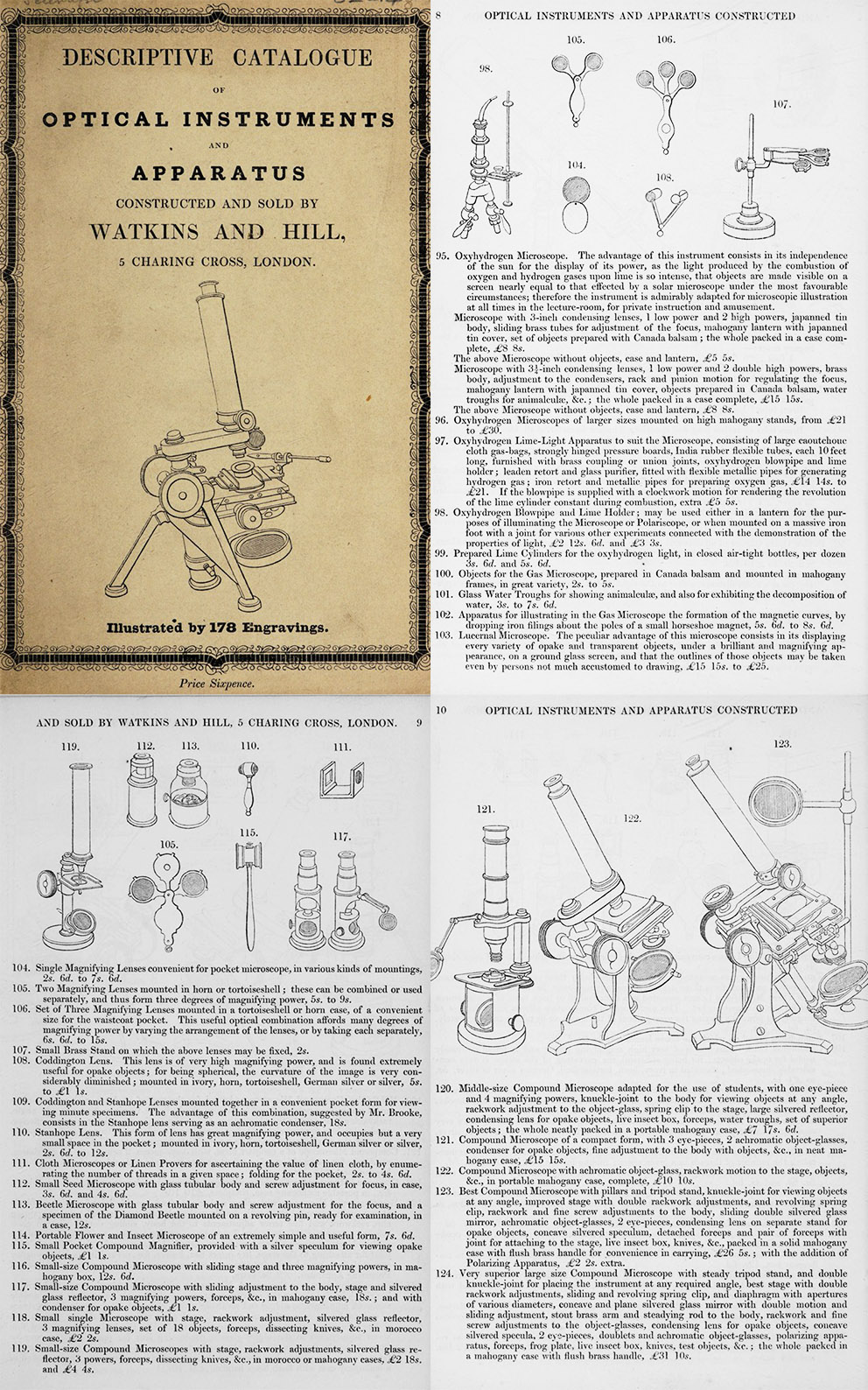

Figure 14.

Cover and excerpts from a ca. 1850 Watkins and Hill Catalogue (below):

Figure 14. Cover and excerpts from a ca. 1850 Watkins and Hill Catalogue. The image on the cover is presumably their item 124, "a very superior large size compound microscope with steady tripod stand", and was probably manufactured by Powell and Lealand.

Francis Watkins born on April 25, 1723, in Radnor, Wales, He was the fourth child, and fourth son, of Jeremiah and Mary (nee Whitney) Watkins. Jeremiah had married into a wealthy family, and was considered to be a gentleman farmer. He had the money and the intellect to expand his wealth through investments in real estate. Son Francis learned well, and similarly gained substantial wealth from his investments in land. That served him well over the years, as the vagaries of the optical and scientific apparatus business did not financially harm Watkins in the same way as it did other colleagues, such as John Cuff or James Ayscough.

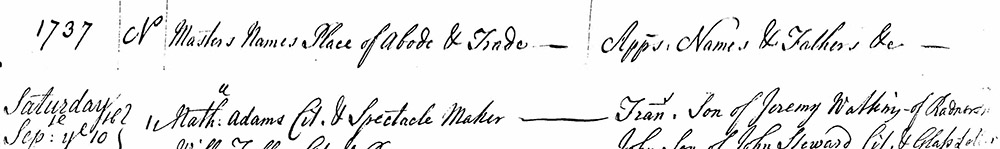

Francis was sent to London in 1737, to apprentice as an optician with Nathaniel Adams (ca. 1707 - 1741) (Figures 15 and 16). Adams had previously been an apprentice with the noted optical instrument-maker Edward Scarlett (1688-1743). At that time, Adams was Optician to Prince Frederick, the Prince of Wales. Jeremiah Watkins had evidently purchased what promised to be a solid future for young Francis.

Unfortunately, Nathaniel Adams died in March, 1741. He was only 34 years old, so he presumably died from one of the infections that ravaged London in those times.

As Francis Watkins had not yet completed his apprenticeship, new arrangements had to be made. It was decided that he would continue his apprenticeship with Edward Scarlett, Adams' former master. A journeyman Spectaclemaker who worked for Scarlett, Henry Walder, was assigned to supervise Watkins' education.

Scarlett died in 1743, and his son, also named Edward, took over the business. The younger Scarlett assumed responsibility for Watkins' apprenticeship. Then Francis Watkins' direct mentor, Henry Walder, died a few years later (at the age of only 26).

Despite the deaths of three masters and mentors, Francis Watkins completed his apprenticeship and was made a Freeman of the Spectaclemakers' Company in 1746.

He then opened his own shop, under the sign of "Isaac Newton's Head" at 5 Charing Cross (Figure 17). This was the same building that had formerly been occupied by Nathaniel Adams, and in which Watkins had served much of his apprenticeship. Watkins soon acquired Adams' former position of Optician to the Price of Wales.

Soon after opening his shop, Watkins made substantial improvement to the design of microscopes. Prior to the 1740s, the tripod-mounted instruments of Culpeper and his mimics were state-of-the-art for compound microscopes. During the early 1740s, scientist Henry Baker (1698-1774) worked with optician John Cuff (ca. 1708 - ca. 1782) to develop a compound microscope with an open stage that would make it easy for the user to manipulate specimens, which resulted in the "Cuff"-type microscope (e.g., Figure 6). Within a few years, Watkins had gone beyond Cuff's design and developed a lightweight, yet solid, tripod-mounted microscope (Figures 1-3). Additionally, Watkins placed a hinged joint in the column, permitting the user to incline the microscope to a comfortable working position. He published a book on his microscope developments in 1754, L'Exercise du Microscope, written in French (Figures 3, 4, and 18).

In 1748 or '49, Francis Watkins married Clarinda Walder, the widow of his former instructor. The pair had two children, both girls. In addition, their household included the two children from Clarinda's first marriage. The younger of those, daughter Elizabeth, married one of Watkins' former apprentices, Addison Smith, on April 7, 1763.

Another of Watkins' apprentices, Henry Pyefinch (lived ca. 1740 - 1790, apprenticed 1753 - 1760)), went on to have a relatively distinguished career. Pyefinch's microscopes are occasionally seen in collections and at auctions.

As did his father, Francis made shrewd investments in real estate. That provided him with a steady income that was relatively immune from the vagaries of the optical and scientific instrument business.

Due to this additional income, Watkins was able to make further speculations. Importantly, he was able to help his son-in-law, Addison Smith, establish his own shop in 1763. That investment came with strings, and Watkins was a partner in Smith's business for at least the next ten years.

Watkins' solid financial situation probably also set helped set the stage for a long-running legal battle that resulted in novel rulings on patent law, while also establishing the fortunes (and lack thereof) for many London optical workers.

A consequence of magnification through glass lenses is that all wavelengths do not refract at the exact same angles. Thus, non-achromatic lenses produce images that blur to some extent, with a red image offset from a blue image. This effect is made worse when multiple lenses are aligned, as with a compound microscope or a telescope. Chromatic aberration was a significant flaw in the use of telescopes in nautical and military matters. Although Isaac Newton predicted that chromatic aberration was impossible to correct, various optical researchers continued to investigate the problem. During the early 1700s, several investigators hit upon the idea of matching lenses of different compositions/densities, discovering that pairs of lenses that were made from different types of glass tended to cancel out each other's chromatic aberration. In particular, Chester Moore Hall (1703-1771), a lawyer and scientifically-curious man, discovered that paired combinations of flint and crown glass could essentially eliminate chromatic aberration.

John Dollond (1707-1761) later learned of that work, and conducted his own experiments with paired lenses made of flint and crown glasses. By the late 1750s, Dollond had refined his work to the point that he was ready to market an achromatic telescope. But first, he decided to protect his lens combination with a patent. Being in a relatively cash-poor situation, Dollond turned to the more-affluent Watkins for financial support. Watkins paid £200 for the patent application. In exchange, the two men would each be able to produce and sell the new achromatic telescopes, with each providing the other with a portion of their receipts. Dollond made all of the lens combinations, thus keeping the construction details secret from his partner.

Soon after the patent was approved in May, 1758, John Dollond made a presentation on the telescope lens combination to the Royal Society. As a consequence of this invention, John Dollond was awarded the Copley Medal by the Royal Society, and later made a Fellow.

Soon after Dollond's presentation, colleagues informed Watkins of the earlier work of Hall and others. Watkins later stated that Dollond subsequently told him of his adaptation of that work, leading Watkins to conclude that Dollond had not actually invented anything new, and that the patent was not valid. Moreover, many other London opticians felt the same way.

After John Dollond died in 1761, his son and heir, Peter Dollond (1731-1820), sought to get out of the partnership with Watkins. After some legal wrangling, it was terminated on May 6, 1763, with Dollond repaying Watkins his original £200 plus an additional £30. Peter Dollond then went after Watkins and partner/son-in-law Addison Smith for their continued production of "Dollond"-type achromatic telescopes. The conclusion of that case set a new precedent in English law, with the ruling that, although the Dollonds had not invented the idea of combining flint and crown glass lenses, they were the first to publicly announce it and bring it to market.

Francis Watkins was Master of the Spectaclemakers' Guild at that time, so he led the Guild's legal dispute of the Dollond patent. Unfortunately for them, political issues at court intervened, and their case did not get anywhere.

Dollond then went on to sue Watkins again, who had not ceased production of achromatic telescopes. Other manufacturers were also targeted.

Despite these distractions, and likely buoyed by income from his investments, Francis Watkins' optical business flourished. Addison Smith also did very well for himself, including development of a patentable improvement in eyeglasses in 1783, and was able to move to a home away from his shop. Around that same time, Watkins decided to retire from the optical trade. His wife, Clarinda, had two daughters from her previous marriage, and together they had produced a son and a daughter, but neither the son nor sons-in-law wanted to take over Watkins' business (Addison Smith was well set with his own firm). Francis Watkins therefore, in 1784, passed management of his optical business to two sons of his eldest brother.

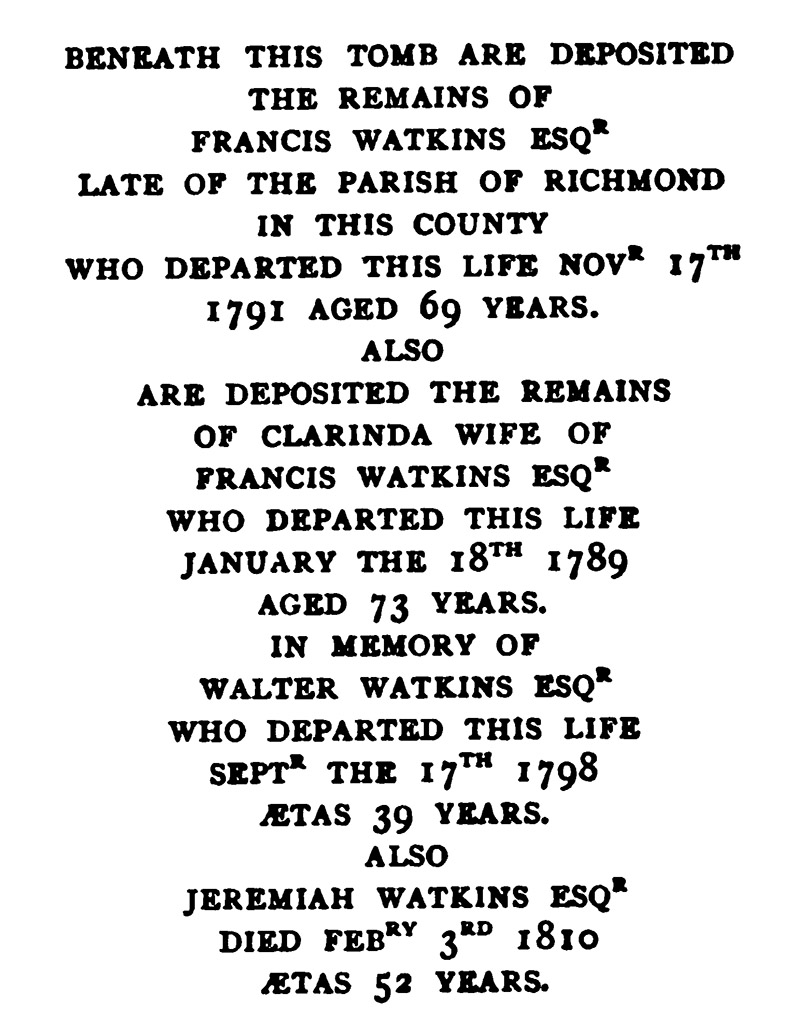

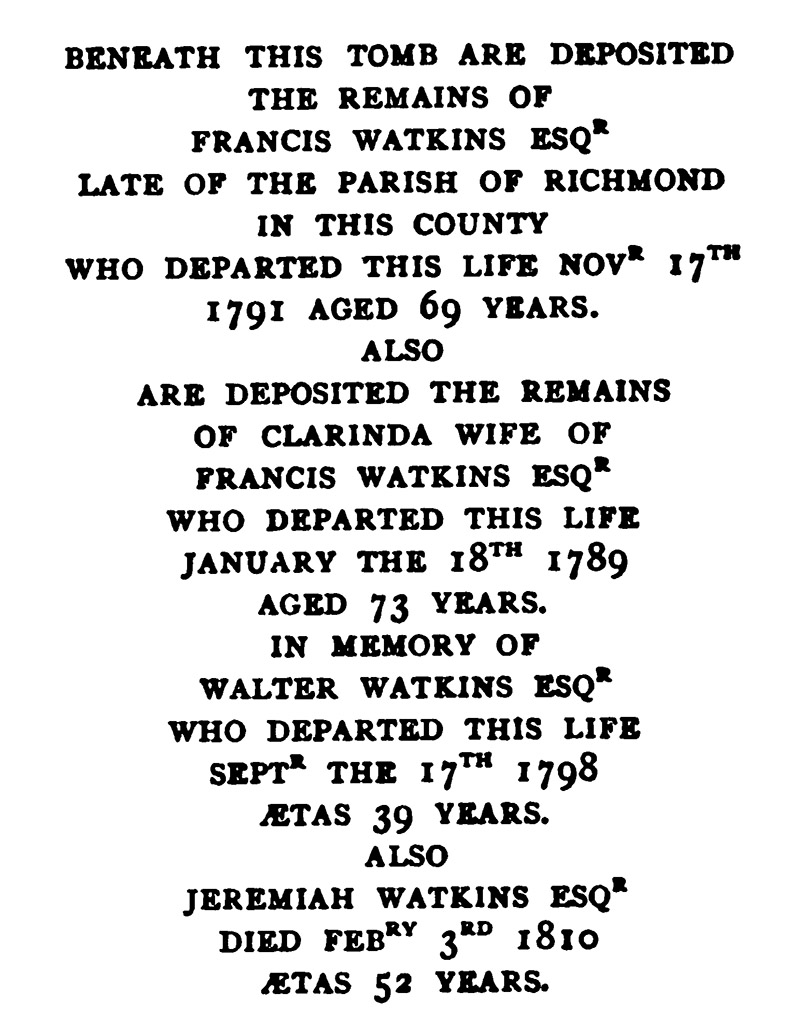

Francis and his wife retired to the wealthy suburb of Richmond. Clarinda died in 1789, and Francis died on September 17, 1791.

Addison Smith died on March 14, 1795. His estate furnished head and foot stones for his grave in July, 1795, a wealthy extravagance.

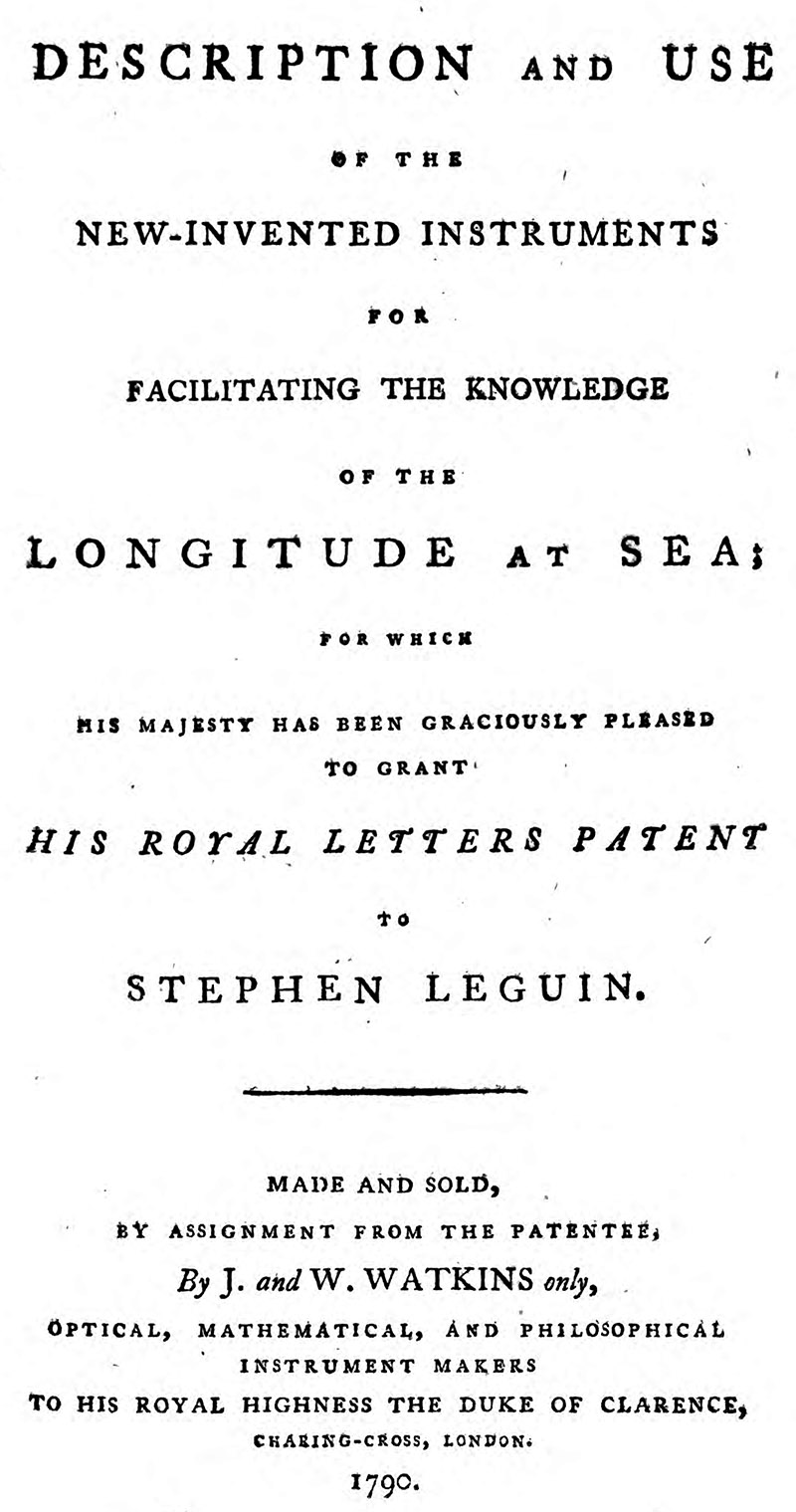

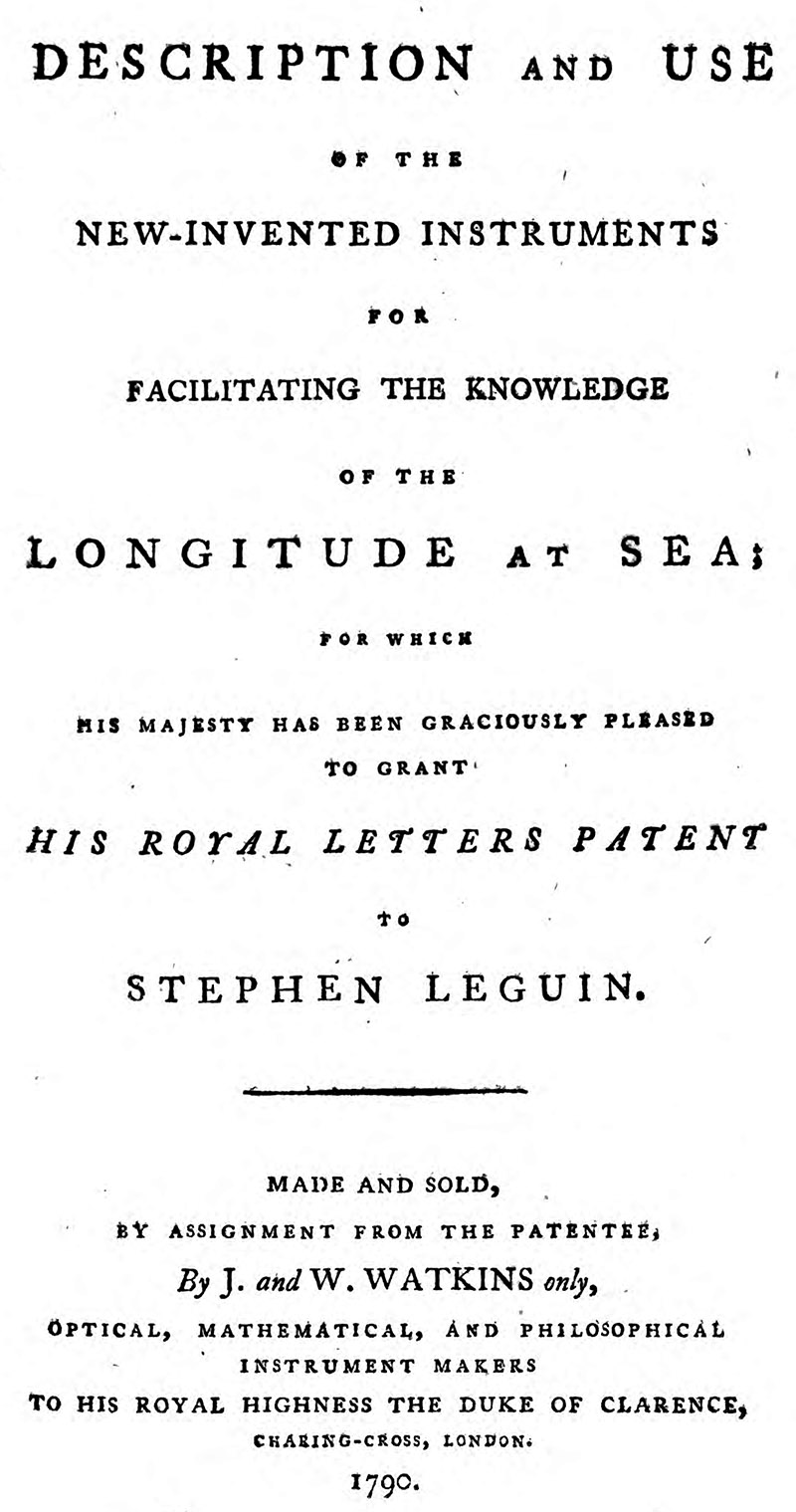

Jeremiah and Walter Watkins took over management of the Watkins business in 1784, although they did not receive ownership until Francis' death in 1791. Jeremiah's training is not known, although his subsequent success indicates that he was either an optician or sufficiently well-versed in management such that his uncle's foremen were enabled to operate the business. His younger brother, Walter, was trained as a printer, and likely facilitated publication of books such as Stephen Leguin's Description and Use of the New Invented Instruments for Facilitating the Longitude at Sea (Figure 24).

Jeremiah Watkins married Mary Fletcher on July 21, 1792. Their second son, Francis, was born on March 16, 1796, and would later inherit the Watkins optical business. Mary Watkins died on November 19, 1798. Jeremiah remarried in 1801, to Charlotte Walker.

Walter Watkins died on September 17, 1798, a month before his 39th birthday, under what appear to be scandalous circumstances. Gee reports that Walter Watkins was married to Sarah Greenough, but he was not with her on the night of his death. According to The Gentleman's Magazine, "Elizabeth Walker deposed that on Monday evening the deceased (Watkins) met her near where she lodged, at Mr. Gordon's house, a perfumer, in New Compton-street, Soho, and asked if he should see her home; she answered, 'Yes, Sir, if you please'. On going up stairs, he said the house smelt strongly of paint, and on entering the room sat himself down by the window, while the deponent was lighting her candle by the fire, that there he fell into a fit; he asked for a little water, which was given to him, but he could not swallow. The witness bathed his temples with hartshorn, and washed his face; but, seeing him dangerously ill, and attempting to vomit, without having the power to bring up scarcely any thing from his stomach, she called up Mrs. Gordon, the mistress of the house, and other persons, to his relief". A local apothecary was summoned, who found Watkins on the landing outside Elizabeth Walker's apartment, rather inside where he had taken ill: "Robert Smith, apothecary, of Compton-street, said he was sent for at nine the same evening to attend a sick person at Mr. Gordon's house; on going up stairs he found the deceased on the landing-place of the two pair of stairs, with two or three women and a young man, who supported him; he enquired into the cause, and, observing him violently agitated in his stomach, he prescribed warm water, to provoke an emetick in the deceased; having discharged a small quantity of animal food, he imagined his stomach was overloaded, which had brought on the disorder, and was the cause of his death". Supported by insight from Watkins' physician, the coroner's jury decided that Walter Watkins, "being a very hearty eater, and having that day more fully than usual satisfied his appetite, an apoplexy had taken place from an overloaded stomach, which was further accelerated by having drunk a quantity of ale, which, tending to inflate the internal system, had produced the direful effect. The Jury, on hearing the evidence, after a short consultation, returned a verdict, that the deceased died in consequence of a fit of apoplexy".

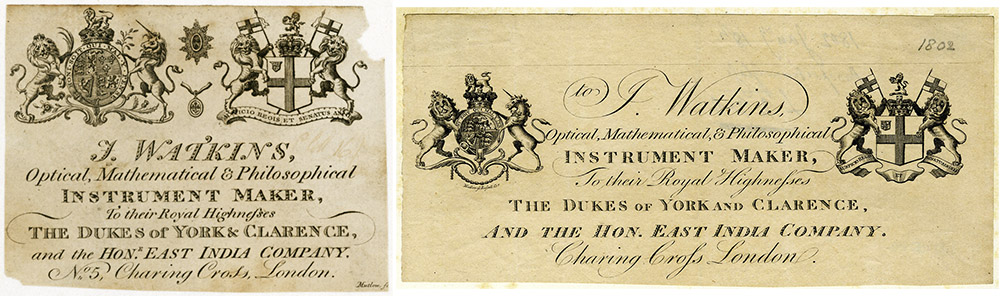

The Watkins business was thereafter known as J. Watkins (Figure 26).

Jeremiah Watkins passed away on February 3, 1810 (Figure 27). The business was put in trust for his son, Francis, who was then not quite 16 years old.

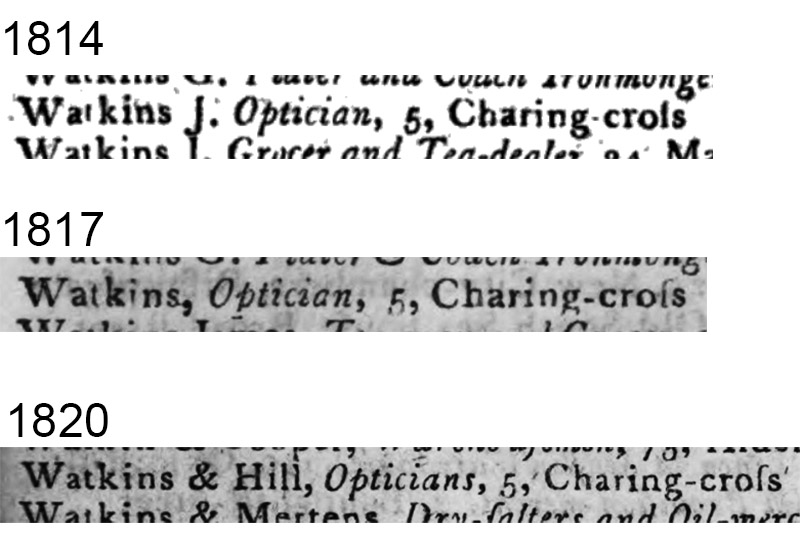

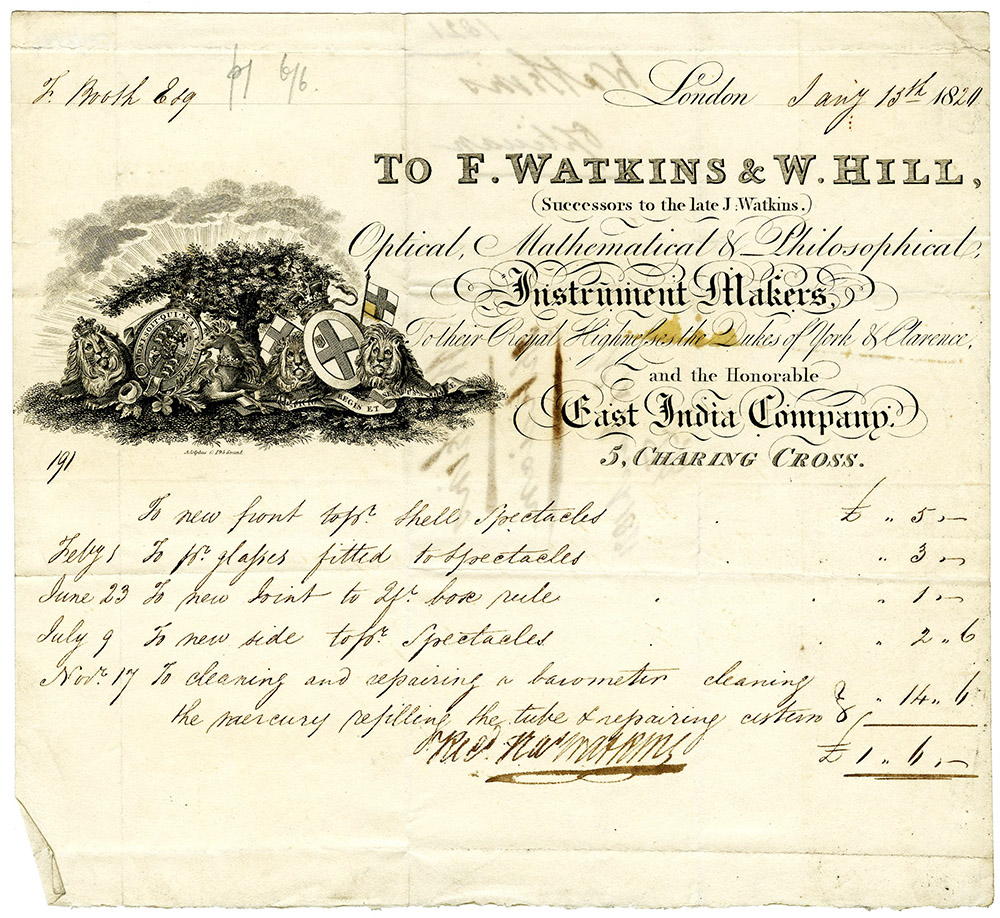

William Hill, who had reportedly been Jeremiah Watkins' foreman, managed the optical business for Charlotte Watkins and her minor son. The firm does not appear to have adopted the name "Watkins and Hill" until after 1817 (Figure 28). It is reasonable that Hill would not have immediately been made a full partner, as he probably could not have afforded to buy into the business in 1810.

Watkins and Hill appears to have begun operating under that name in 1817-1818. The business was listed as such in the 1818 edition of Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine. This name continued until the business was terminated in 1856, long after both Watkins and Hill had died.

Francis Watkins married Mary Ann Hitchcock on April 23, 1823. They had two children, neither of whom inherited the optical works.

This younger Francis showed considerable interest in the sciences. For example, he presented "On the decomposition of water by thermo-electricity" in 1838.

Little has been found about William Hill. The 1841 census listed him as being 65 years old, although the rules of that census were for people to round off their ages. He was not originally from Middlesex. In 1841, Hill lived at 5 Charing Cross with Watkins and two young female servants. Hill's will did not mention any family, and he bequeathed his estate to Francis Watkins' widow, Mary Ann.

Francis Watkins died in 1847, probably during May, since his will was proved on May 28, 1847. William Hill filed a codicil to his will after May 22, 1847, leaving his estate to Mary Ann Watkins. Hill's will was proved on June 26, 1847.

With the death of both partners, Mary Ann Watkins was now the owner of Watkins and Hill. She then employed an employee of her husband, Abraham Day, to manage the business. The 1851 census shows Day as living at 5 Charing Cross. Also living at the shop were a housekeeper, Mary Ann Scarlett, and her husband, John Scarlett - a "brass worker" who presumably worked for the Watkins and Hill business. Although I have not worked through their genealogies, it would be ironic if John and Mary Scarlett descended from the original Francis Watkins' master.

Gee noted that Watkins and Hill were essentially rudderless after the partners died in 1847. Mary Ann had no training in the optical and scientific busines (and probably no inclination for it), and, while Abraham Day was likely a competent workman, he wouldn't have been trained to guide a progressive business.

A Watkins and Hill catalogue from around 1850 listed microscopes and other instruments that were essentially the same as could be obtained from other suppliers (Figure 14, above). Those similarities suggest that many, if not all, of the mid-1800s microscopes from Watkins and Hill were brought in from wholesale manufacturers.

Watkins and Hill exhibited at the 1851 Great Exhibition in London, but did not win any awards. Exhibition catalogues list that they displayed, "Large plate electric machine. Electro magnetic engine. Sextants, theodolites, levels, &c ... Improved barometric vacuum gauge. Sectional models of steam engines ... Rifle, with telescope".

Mary Ann Watkins sold the business to Elliot Brothers in 1856. They maintained the shop at 5 Charing Cross until 1858, when they condensed their operations into a single shop in The Strand.

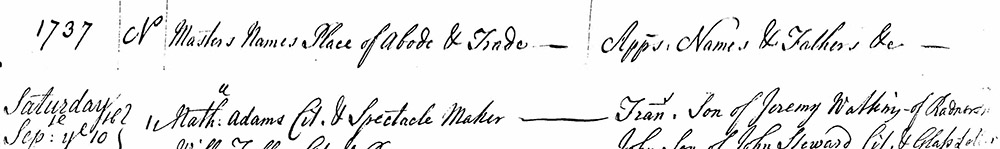

Figure 15.

Excerpt from a record of apprenticeships, listing the binding of "Frans, Son of Jeremy Watkins of Radnor" to "Nathn Adams Cit. & Spectacle Maker" on Saturday, September 10, 1737.

Figure 16.

The base, with engraved mirror, of a ca. 1730s Culpeper-type microscope by Francis Watkins' first master, Nathaniel Adams. It states that he was the Optician to Prince Frederick, Prince of Wales. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://www.mhs.ox.ac.uk/collections/imu-search-page/record-details/?thumbnails=on&irn=14650&TitInventoryNo=31636.

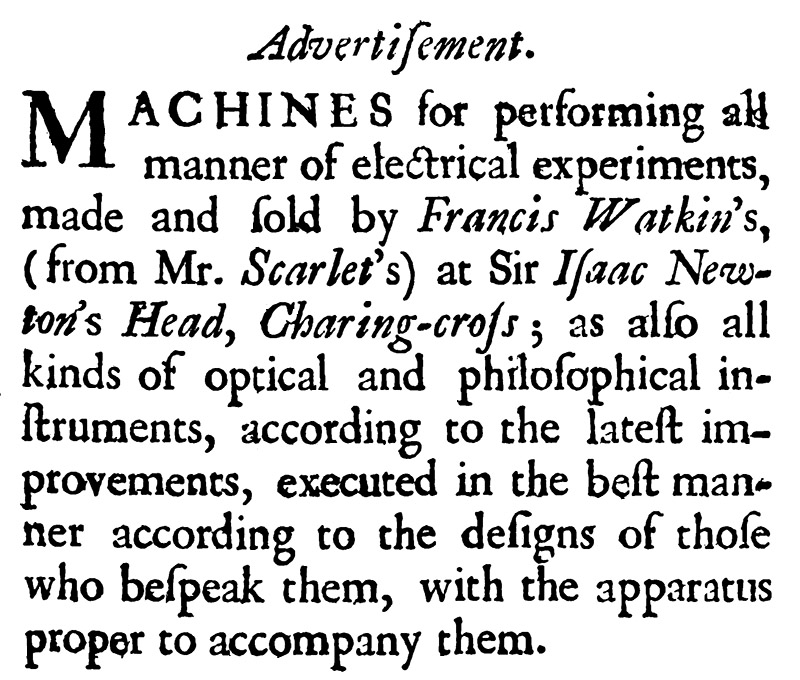

Figure 17.

1747 advertisement by Francis Watkins, from his booklet "A Particular Account of the Electrical Experiments Hitherto Made Publick, with Variety of New Ones, and Full Instructions for Performing Them".

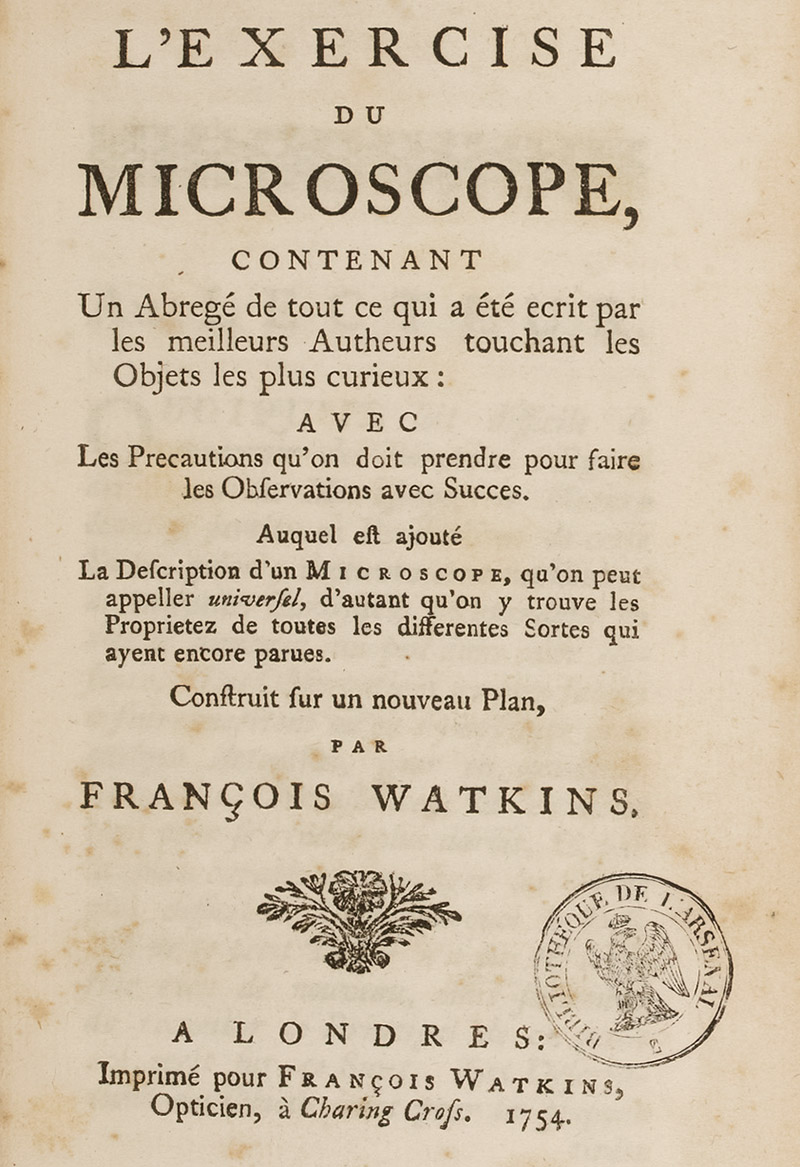

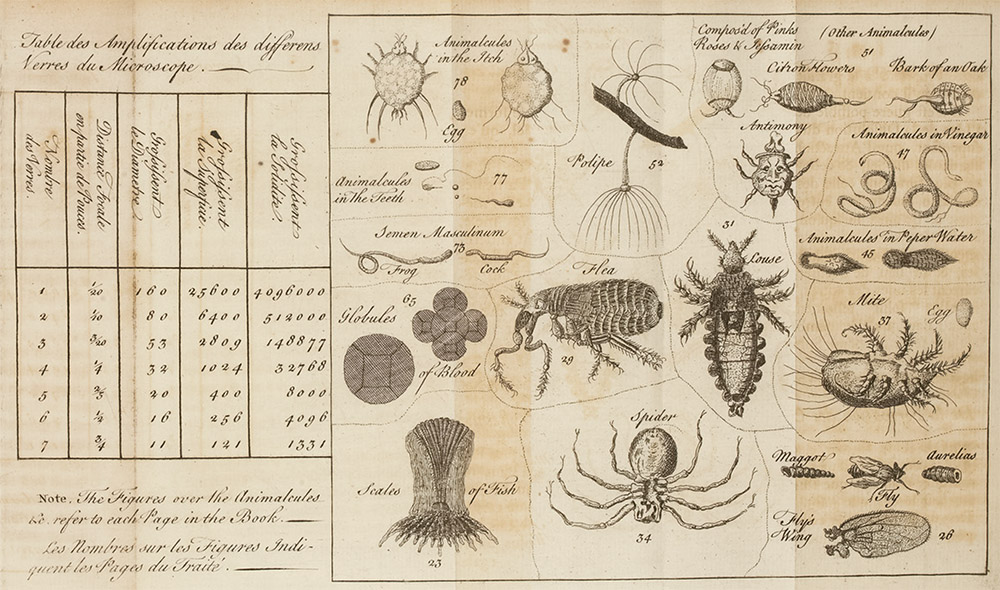

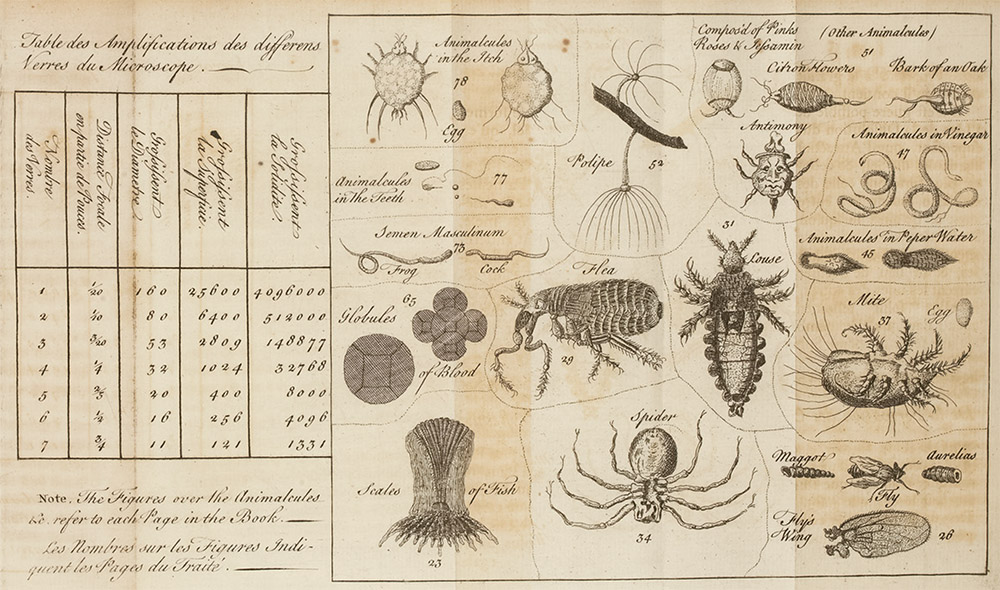

Figure 18.

Title page and illustrations of magnified microscopical specimens from Francis Watkins' 1754 "L'Exercise du Microscope".

Figure 19.

Brass ruler by Francis Watkins. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet sale site.

Figure 20.

The 1750 contract that bound Addison Smith to Francis Watkins for seven years. Smith was described as the nephew of Thomas Anderton, a vintner of Westminster, and was thus likely an orphan in the care of his aunt and uncle. Of note, the apprentice contract was signed by James Ayscough, a well-known microscope-maker.

Figure 20B.

A reflecting telescope by Watkins and Smith. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

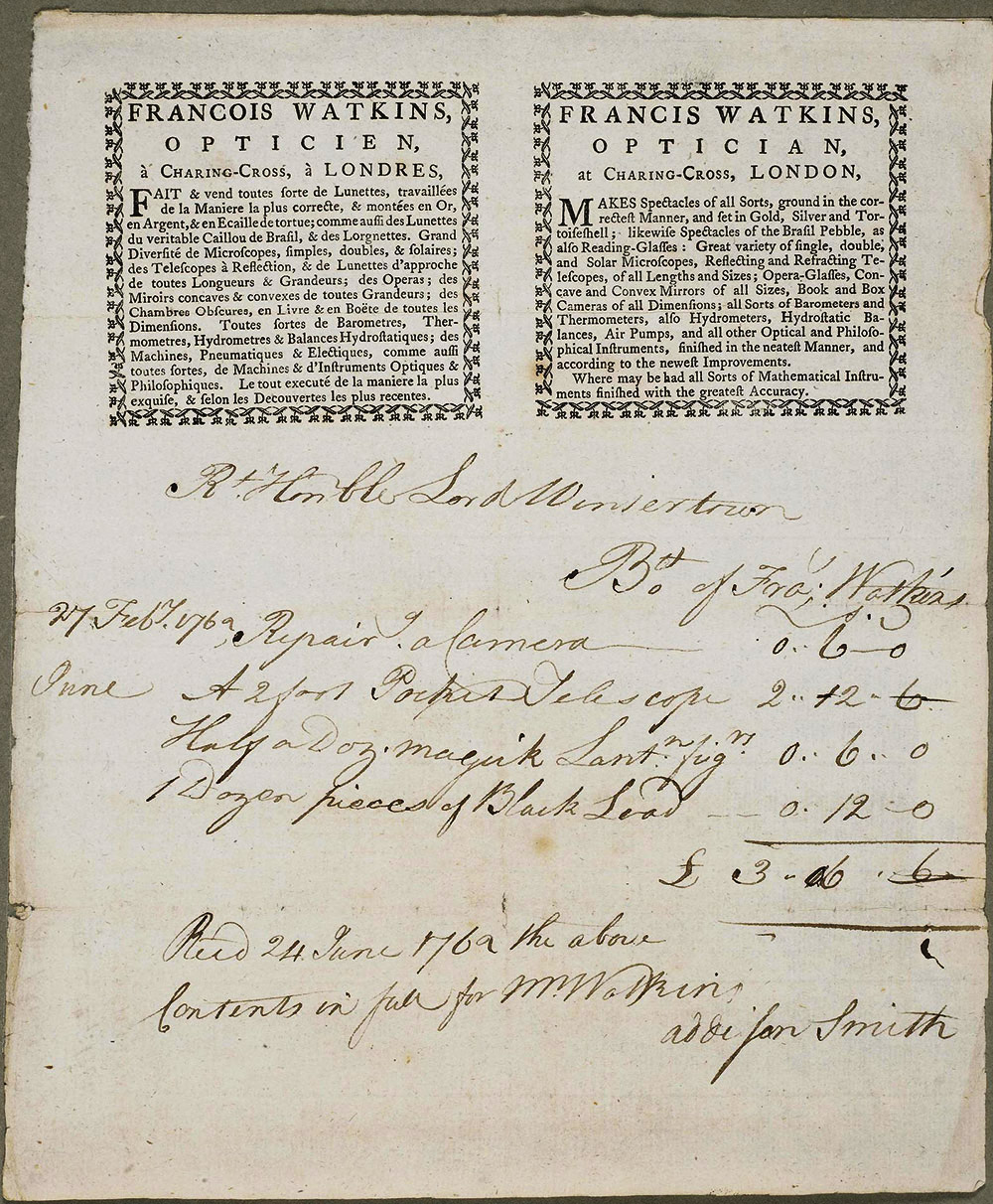

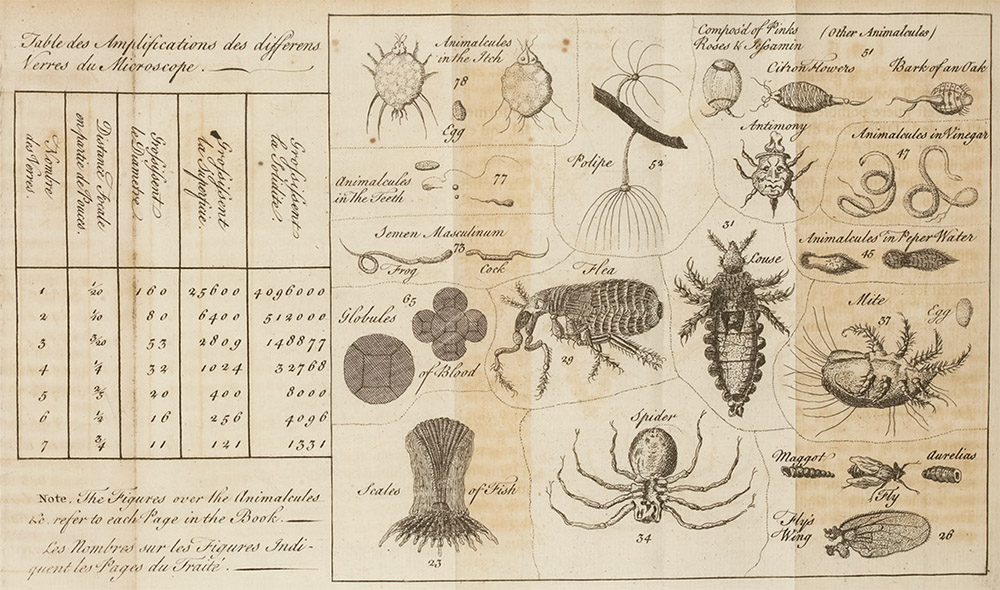

Figure 21.

Francis Watkins' billhead, dated June 24, 1762. It was signed by Addison Smith, confirmation that Smith continued to work for Watkins after the conclusion of his apprenticeship. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://www.britishmuseum.org

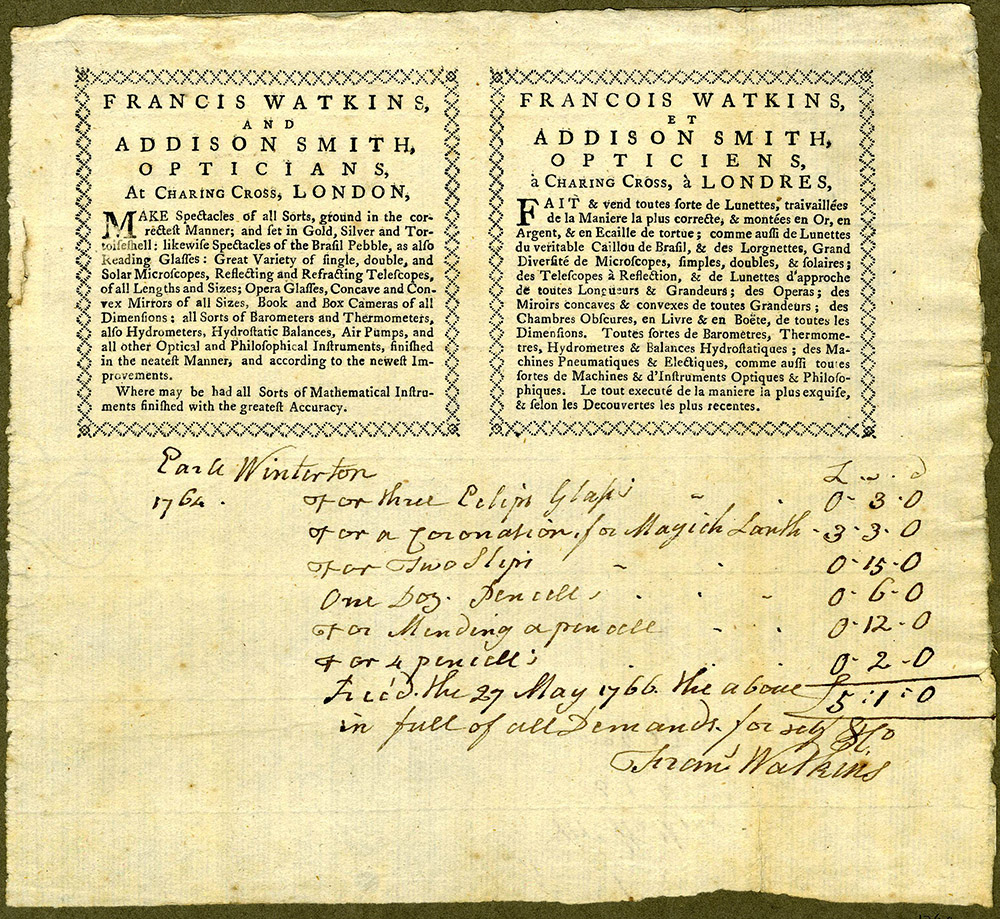

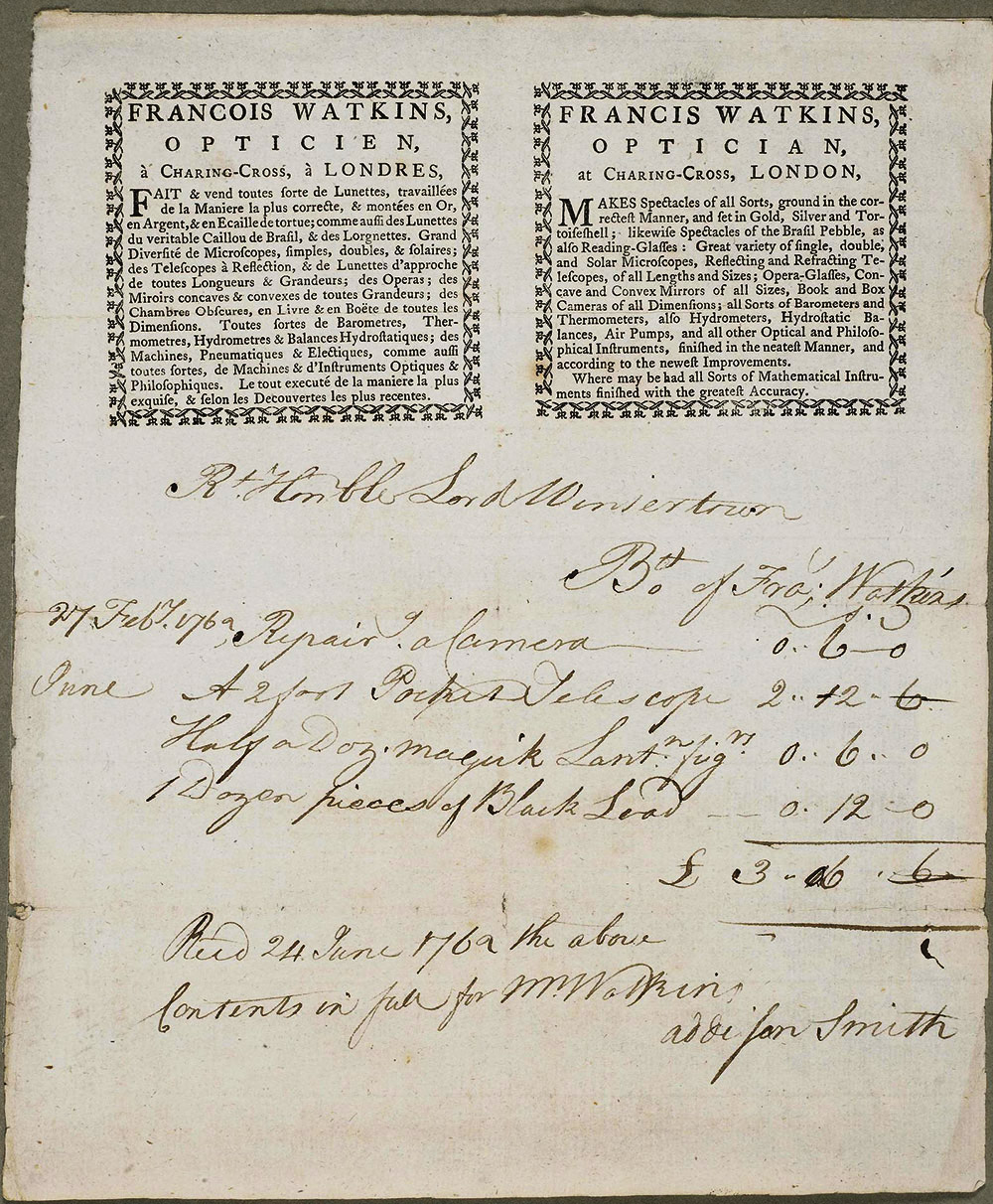

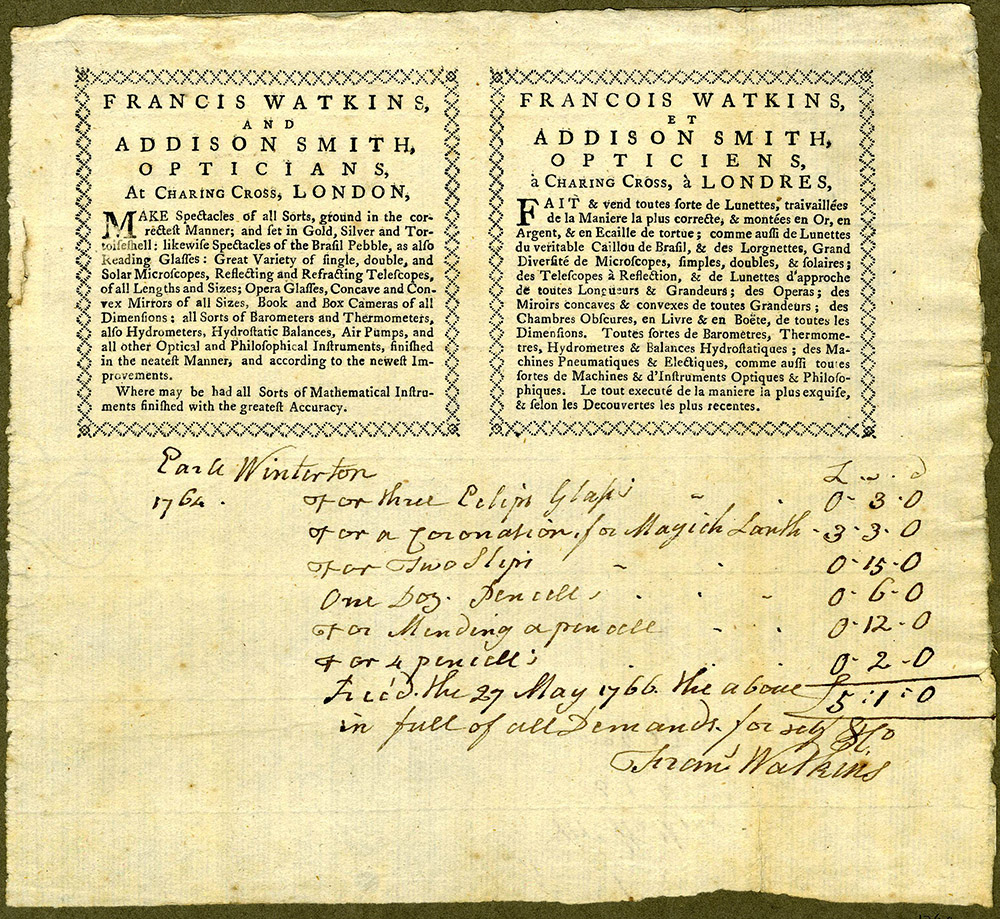

Figure 22.

Billhead from Watkins and Smith, initially dated 1763 and closed on May 27, 1766, and signed by Francis Watkins. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://www.britishmuseum.org

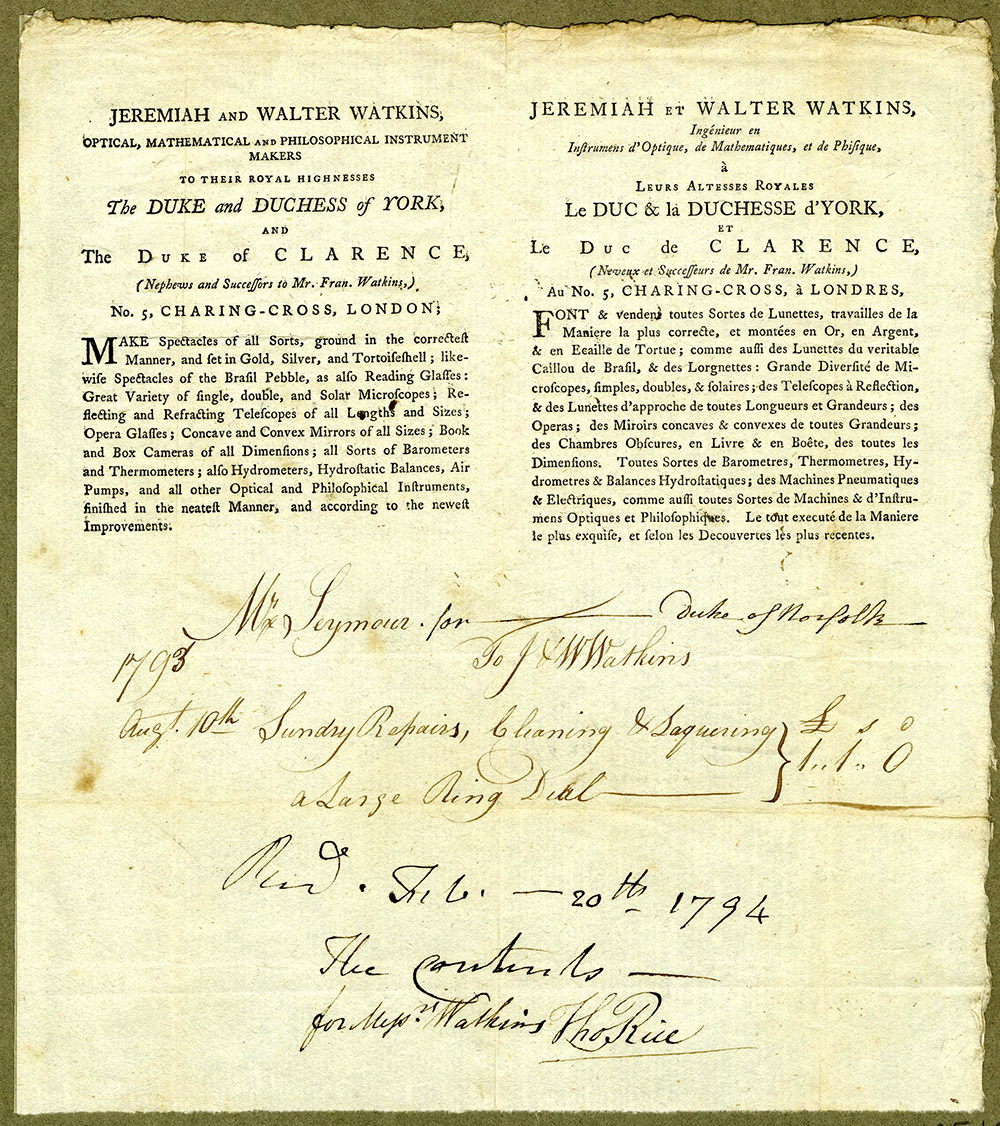

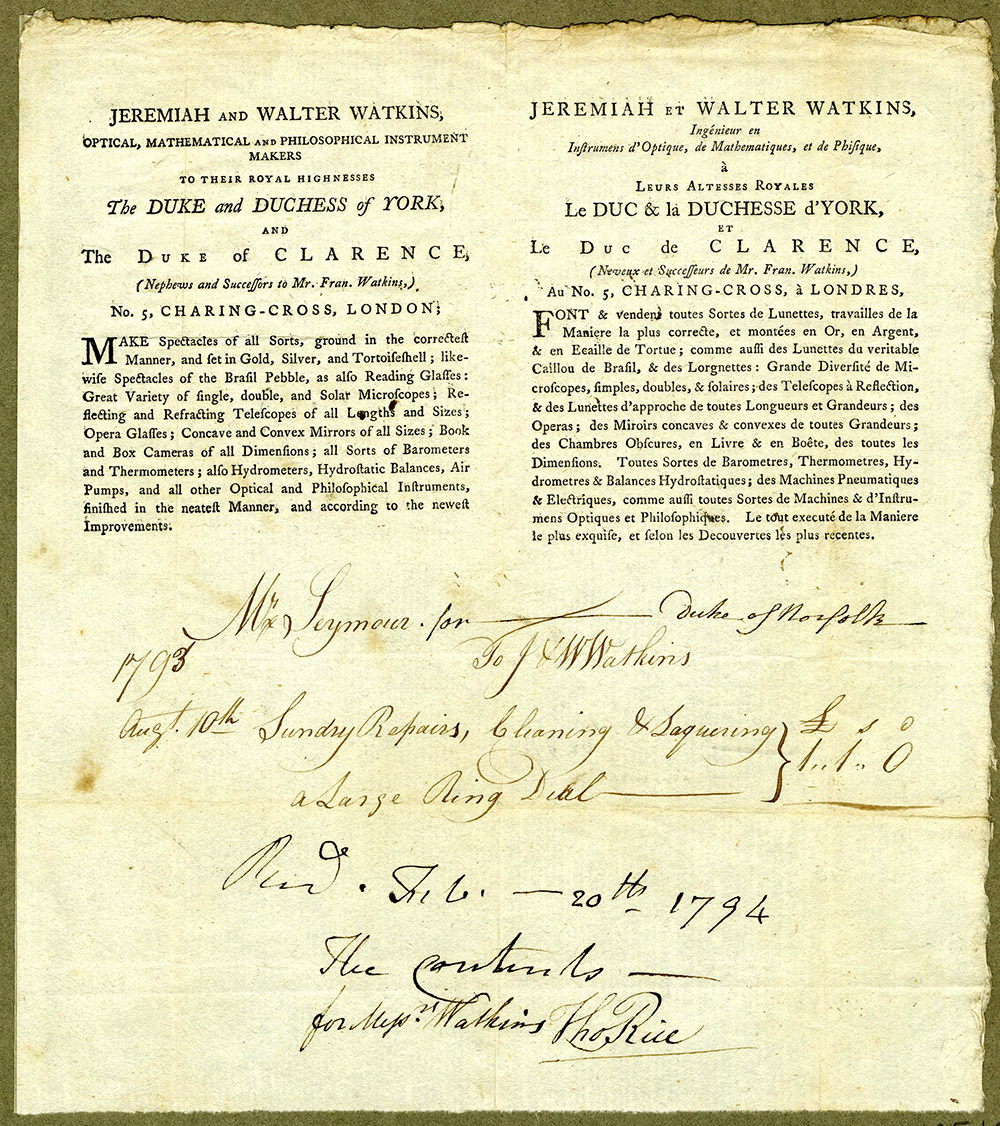

Figure 23A.

Dated 1794, a billhead from Jeremiah and Walter Watkins and Smith. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://www.britishmuseum.org

Figure 23B.

Ca. 1790 compass by J. and W. Wakins. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet sale site.

Figure 24.

Title page from a book published in 1794 by J. and W. Watkins.

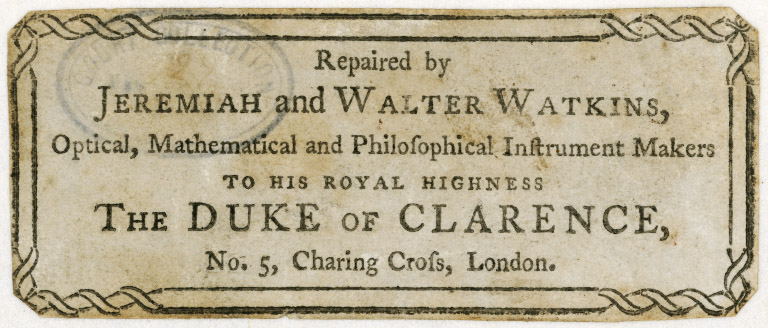

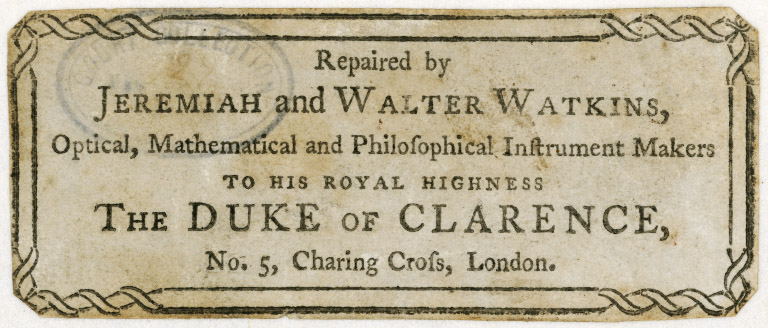

Figure 25.

Undated trade label of Jeremiah and Walter Watkins. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://www.britishmuseum.org

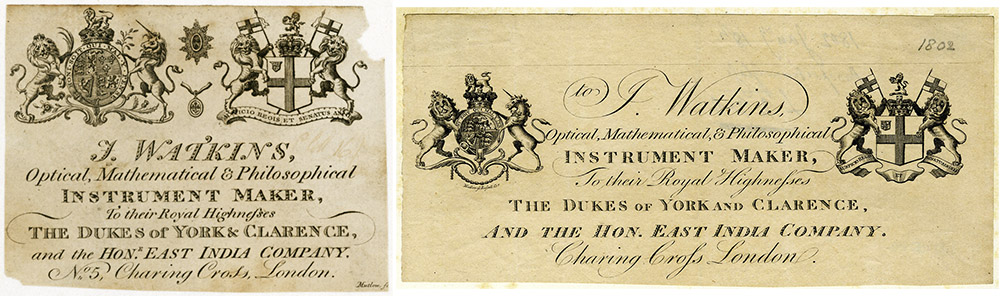

Figure 26.

Circa 1800 trade labels of Jeremiah Watkins. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://www.britishmuseum.org

Figure 27.

Transcript of a memorial plaque to the Watkins family, at St. Giles Church, Camberwell. Adapted from "Fragmenta Genealogica" Vol. 6.

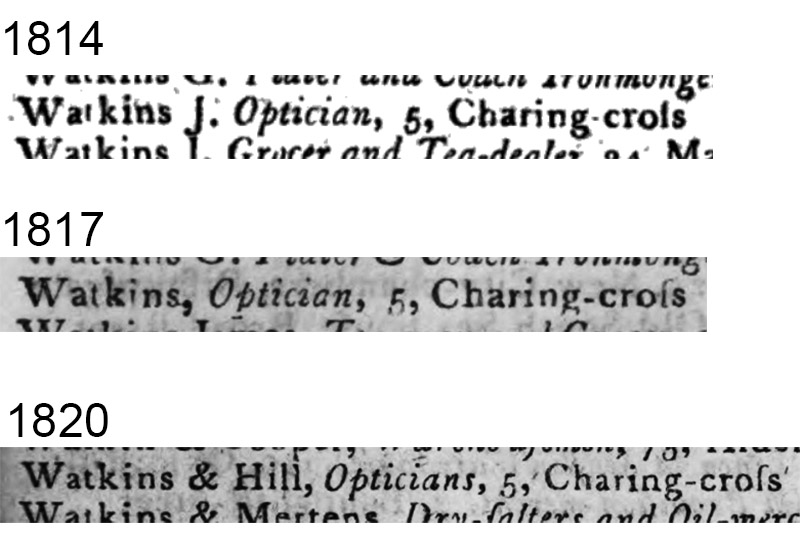

Figure 28.

Excerpts from the "London Post Office Address Book". The business appears not to have changed its name to "Watkins and Hill" until after 1817.

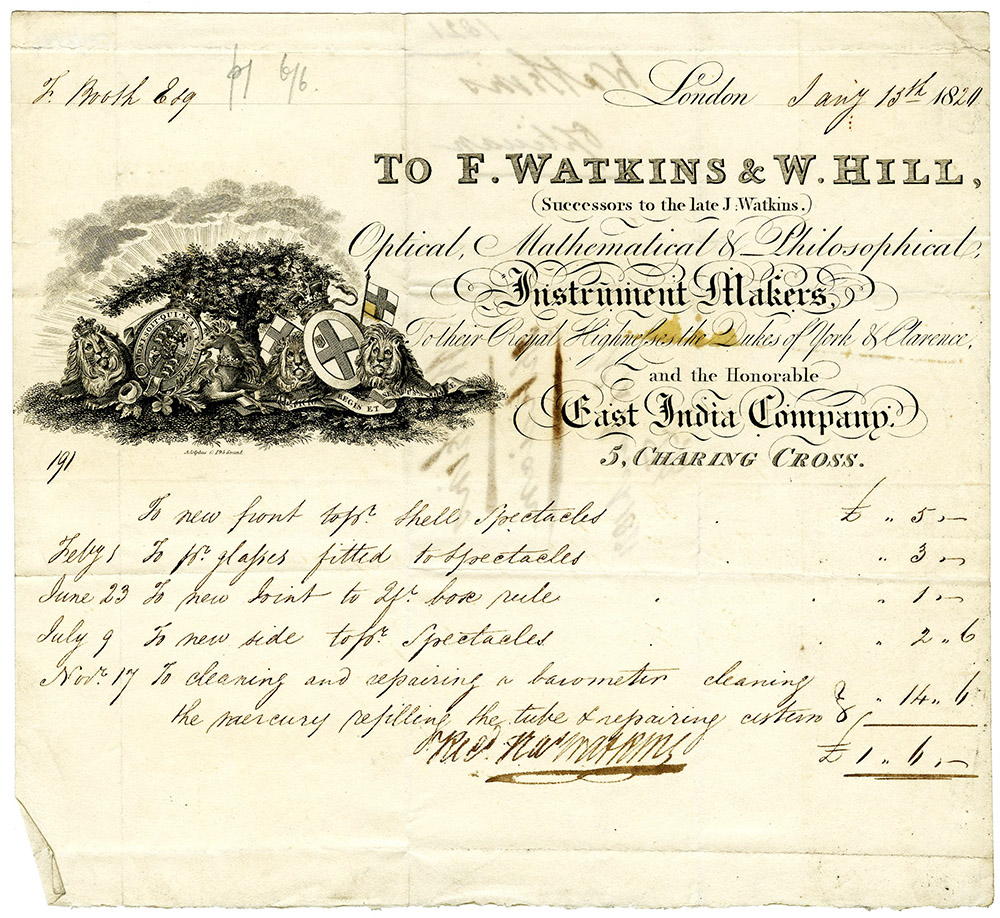

Figure 29.

An 1820 receipt from Watkins & Hill. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://www.britishmuseum.org

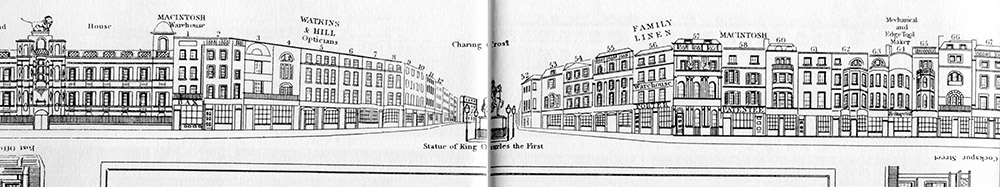

Figure 30.

ca. 1838 street-level view of Watkins and Hill and other buildings at Charing Cross. Their shop, number 5, was adjacent to Trafalgar Square and Nelson's Column (marked by the large rectangle at the bottom of the image), and was directly across from the National Gallery The Watkins / Watkins & Hill businesses had been at that location since 1747. It had previously been occupied by the first Francis Watkins' master, Nathaniel Adams. Adapted from Tallis' "London Street Views, 1838-1840".

Figure 31.

An undated trade label from Watkins and Hill. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://www.britishmuseum.org

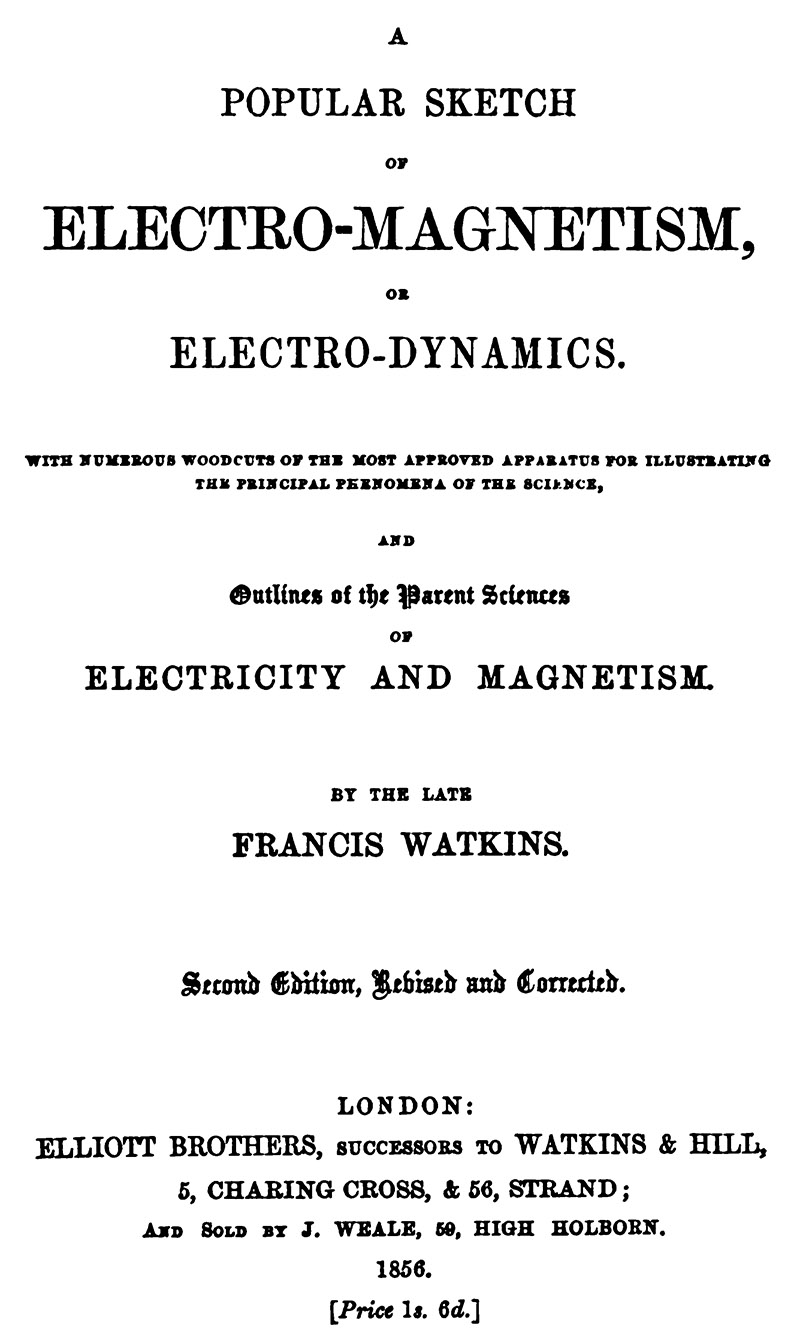

Figure 32.

Title page from the 1856, second edition of Francis Watkins' "A Popular Sketch of Electro-Magnetism and Electro-Dynamics", published by Elliot Brothers, successors to Watkins and Hill.

Figure 33.

A post-1858 trade label from Elliot Brothers. They condensed their previous shop and the one that they acquired from Watkins and Hill into a single site at 30 Strand in 1858 . Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://www.britishmuseum.org

Acknowledgement

Thank you to Jeffrey Silverman and Jurriaan de Groot for providing images.

Resources

The Athenaeum (1857) Advertisement from Elliott Brothers, August 1 issue, page 959

The Athenaeum (1858) "Notice: Elliott Brothers, Opticians to the Admiralty, Ordnance, and East India Company, and successors to Watkins & Hill, beg respectfully to give notice that they have REMOVED from 58. Strand, and 5, Charing Cross, to more extensive premises, No. 30, Strand, formerly Warren's. Illustrated Catalogues by post for 18 stamps", September 4 issue, page 283

Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine (1818) "The patent kaleidoscopes are now made in London, under Dr Brewster's sanction, by Messrs P. and G. Dollond, W. and S. Jones, Mr R. B. Bate, Mess. Thomas Harris and Son, Mr Bancks, Mr Berge, Mr Thomas Jones, Mr Blunt, Mr Schmalcalder, Messrs Watkins and Hill, and Mr Smith", Vol. 3, page 337

Clifton, Gloria (1995) Directory of British Scientific Instrument Makers, 1550-1851, Zwemmer, London, pages 136, 254, and 290-291

Crisp, Frederick A. (1901) Fragmenta Genealogica, Vol. 6, F.A. Crisp, London, page 148

England census and other records, accessed through ancestry.com

Gee, Brian (2016) Francis Watkins and the Dollond Telescope Patent Controversy, ed. by A. McConnell and A.D. Morrison-Low, Routledge, Abingdon

The Gentleman's Magazine (1791) Deaths: "17. At his house at Richmond, Surrey, in his 69th year, Francis Watkins, esq, formerly an eminent optician at Charing-cross", Vol. 70, page 1071

The Gentleman's Magazine (1798) Deaths, Vol. 84, page 907

Kent's Directory of London (1793) "Watkins T. (sic) & W. Opticians, 5, Charing-cross"

Kent's Directory of London (1803) "Watkins J. Optician, 5, Charing-cross", page 209

Leguin, Stephen (1790) Description and Use of the New Invented Instruments for Facilitating the Longitude at Sea, J. & W. Watkins, London

London Post Office Directory (1786) "Watkins Jeremiah, optician, Charing cross"

London Post Office Directory (1812) "Watkins J. Optician, 5, Charing-cross"

London Post Office Directory (1814) "Watkins J. Optician, 5, Charing-cross"

London Post Office Directory (1816) "Watkins, Optician, 5, Charing-cross"

London Post Office Directory (1817) "Watkins, Optician, 5, Charing-cross"

London Post Office Directory (1820) "Watkins & Hill, Opticians, 5, Charing-cross"

London Post Office Directory (1847) "Watkins & Hill, opticians & philosophical instrument makers, 5 Charing cross"

The Monthly Magazine (1801) Marriages: "J. Watkins, esq. of Charing Cross, to Mrs. Walker, late of Stafford", Vol. 12, page 257

Official Catalogue of the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations (1851) pages 31, 52, and 79

Robson's London Directory (1842) "Watkins and Hill, opticians, 5 Charing cross"

Smith, Addison (1783) Visus Illustratus, or, The Sight Rendered Clear and Distinct, Smith, London

Tallis, John (1838-1840) London Street Views, reprinted 2002 by the London Topographical Society, pages 192-193

Watkins, Francis (1747) A Particular Account of the Electrical Experiments Hitherto Made Publick, with Variety of New Ones, and Full Instructions for Performing Them, Watkins, London

Watkins, Francis (1754) L'Exercise du Microscope, Watkins, London

Watkins, Francis (1828) A Popular Sketch of Electro-Magnetism, or Electro-Dynamics, J. Taylor, London

Watkins, Francis (1856) A Popular Sketch of Electro-Magnetism, or Electro-Dynamics, Second Edition, Elliot Brothers, London

Watkins, J, and W. Watkins (1796) A Short Account of the Zimutal, or Invariable Compass, J. & W. Watkins, London

Watkins, Francis (1838) On the decomposition of water by thermo-electricity, The London and Edinburgh Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, page 541

Watkins and Hill (ca. 1850) Descriptive Catalogue of Optical Instruments and Apparatus

Will of Francis Watkins (1847) accessed through ancestry.com

Will of William Hill, with codicil (1847) accessed through ancestry.com