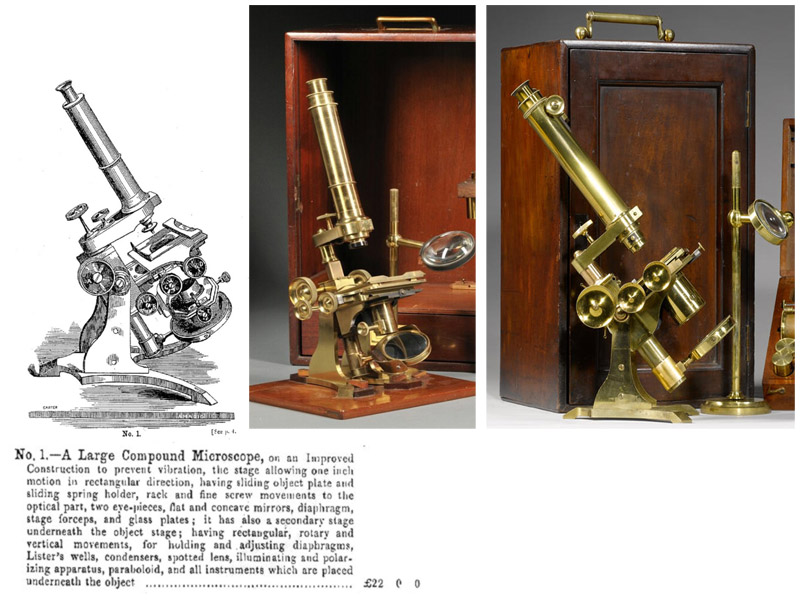

Figure 1. Joseph Amadio’s top-of-the-line, patterned after Ross, with mechanical stage. This retailed for £22 in 1864, and £27 in 1858.

Joseph Philip Amadio, 1812 - 1892

by Brian Stevenson

last updated December, 2022

Joseph Amadio was a successful retailer of microscopes, slides and related equipment, in mid-nineteenth century London. His father, Francis (Francesco), was a well-regarded maker of barometers and thermometers. Both Joseph and his brother, also named Francis, likewise became barometer makers. Joseph later turned to primarily sell microscopes and other optical devices, probably in the mid-1850s. At some point there was a barometer-making partnership of F. Amadio and Son, although which son(s) was involved is not clear. The younger Francis gave up his barometer & thermometer business in the early 1860s, and was taken in by his brother. For a brief period, from about 1863 until Francis’ death in 1866, the microscope business was known as F. & J. Amadio. Further details of the lives of Joseph and his family follow the descriptions of his microscopes and slides.

There are numerous examples of identical microscopes with and without Joseph Amadio’s name on them. Those observations suggest that many or all of his instrument bodies were brought in from outside suppliers. At least one pattern appears to be of French manufacture. Joseph’s training from his father would have primarily dealt with the precision glasswork necessary for making barometers and thermometers. So it is logical that Joseph would maximize quality and profit by making lenses and other glass parts himself, and subcontracting production of brass and other metalwork.

Two Amadio catalogs have been identified. One printed without a date (evidently the first edition) was likely published in 1858, and the third was published in 1864 (as F. & J. Amadio). Advertisements indicate that the second edition was published in 1860. The 1858 and 1864 catalogs contain essentially the same microscopes, with the 1864 prices being slightly lower than those of 1858. The microscopes were similar to those sold by other manufacturers of the time, of moderate price, and likely to appeal to students and middle-class buyers. Amadio’s slides were all brought in, with makers that included prestigious mounters such as Charles Topping, John Barnett, Joseph Bourgogne and John B. Dancer. Amadio evidently had positive relationships with Charles Dickens and other publishers, who wrote numerous supportive articles about Amadio’s products and undoubtedly helped his sales.

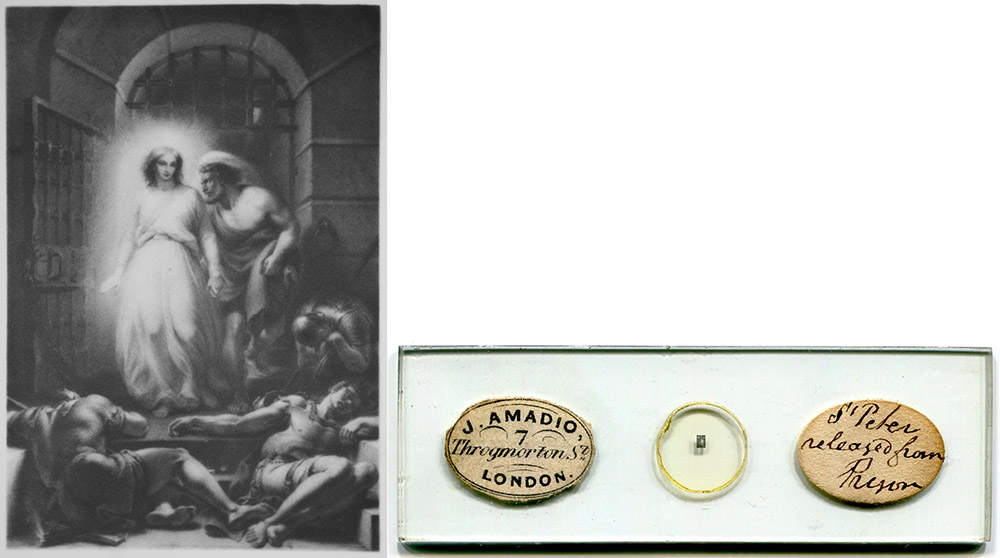

Figure 1.

Joseph Amadio’s top-of-the-line, patterned after

Ross, with mechanical stage. This retailed for £22 in 1864, and £27 in 1858.

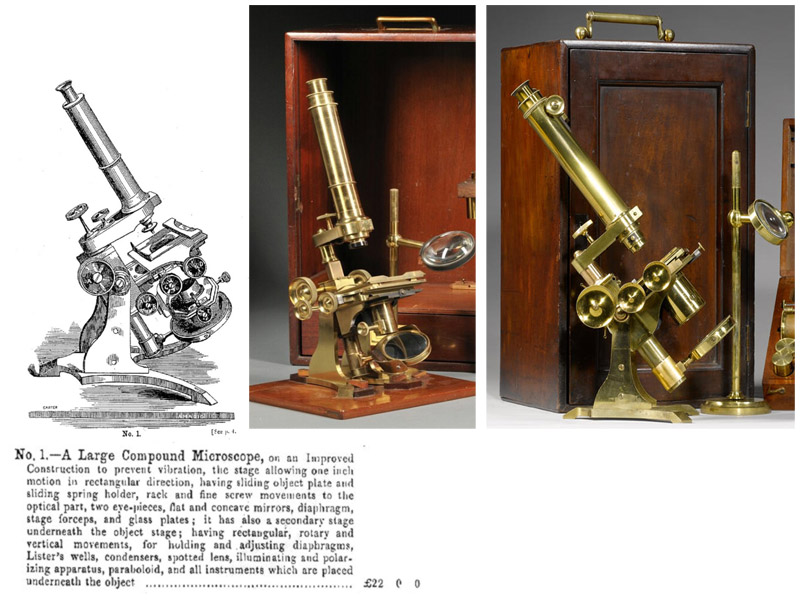

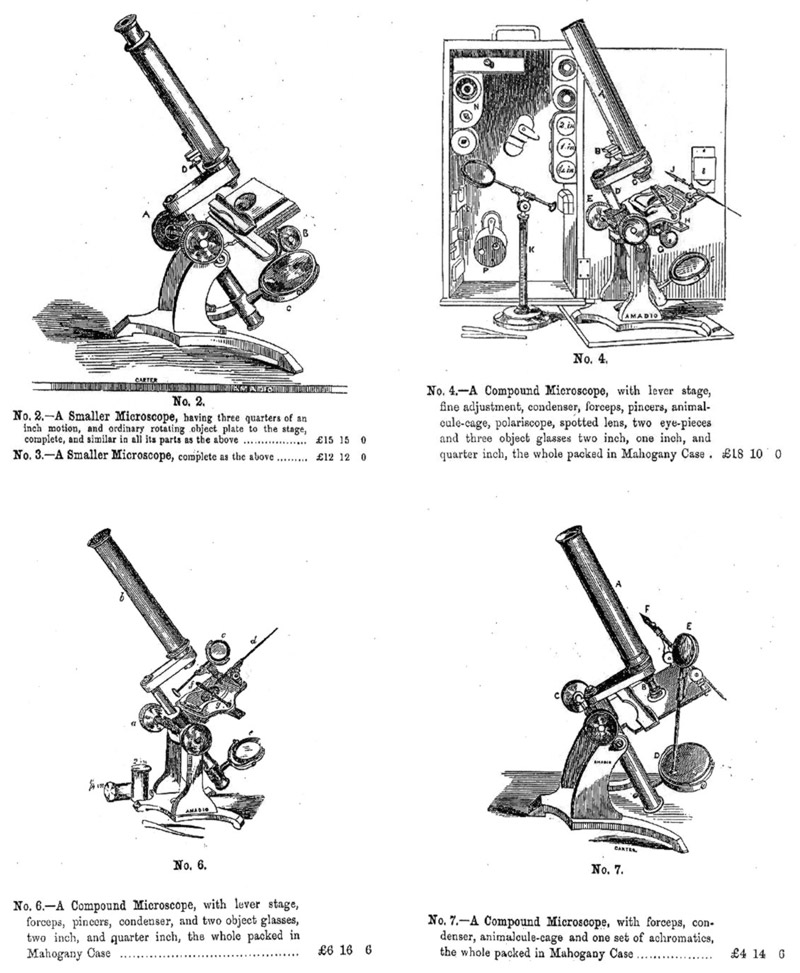

Figure 2.

A significantly simpler model, costing £7 in 1864.

Figure 3.

Less expensive, modeled on styles from an earlier

era. Microscopes with the spread foot are frequently seen, with Amadio’s

signature, even though the 1858 and 1864 catalogs show only the circular base.

That suggests modifications in patterns that were not shown in the catalogs.

The lower left photograph shows a three-part objective lens, likely the type

described in the catalog as accompanying model No. 11. Unsigned microscopes of

this pattern are frequently encountered, suggesting that Amadio brought in the

brasswork, at least, from another manufacturer.

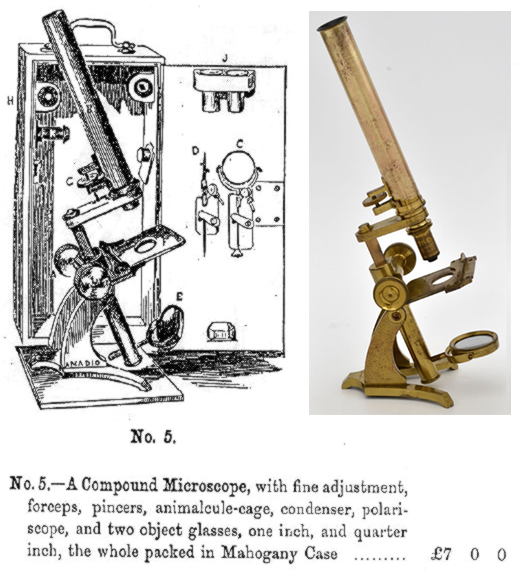

Figure 4.

Amadio's 1858 and 1864 catalogues featured inexpensive, drum-pattern microscopes, likely of French manufacture. Contemporary writers referred to item number 12 as “Amadio’s 18 shilling microscope”,

and recommended it for travels outdoors. The top microscope is engraved "J. Amadio, 7 Throgmorton St., London". The microscope shown at the lower right, with the attached bull's-eye condenser, does not have

a hallmark, but matches the picture of item 12 from Amadio’s catalogs. Similar, unmarked and inexpensive instruments were sold through a number of retailers from the mid-1800s through the early 1900s.

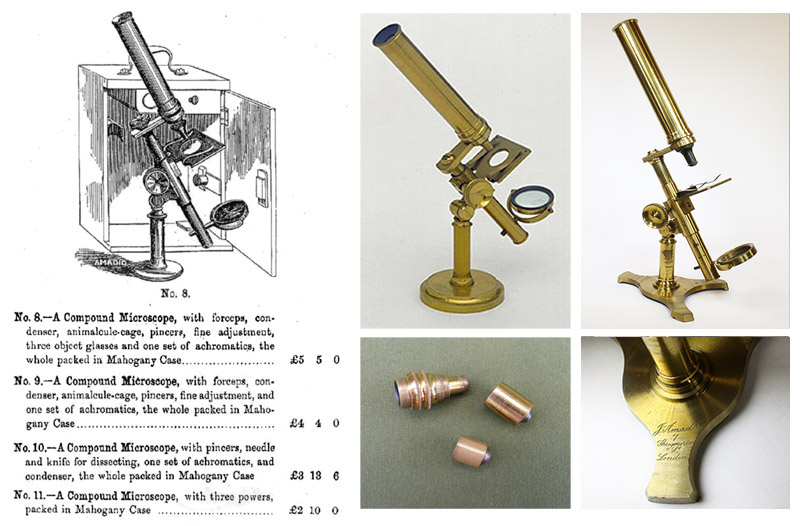

Figure 5.

Other microscope patterns that appeared in the 1858

and 1864 catalogs. Two microscopes that closely resemble Amadio’s number 4 are

known, one of which was sold by John Sack of San Francisco, California, and the

other signed by Aug. Patte, Rue de Rivoli No.168, Paris (

http://www.antique-microscopes.com/photos/sack.htm. These suggest that at least some, and maybe all, of Amadio’s microscope bodies

were brought in from outside. Subcontracting parts was a common practice, and a

reasonable one, too, since a modest-sized shop could not include experts in every

skill necessary to produce all of the glass, brass and steel components of a

microscope.

Figure 6.

Microscope apparatus sold by Amadio in 1864.

Although the Amadios’ shop was at 7 Throgmorton Street, they evidently retained

a location on Moorgate Street, where Francis had previously operated a

business. After Francis’ death in 1866, Joseph moved the microscopy shop to 17A

Telegraph Street, Moorgate Street. The Moorgate addresses may have been the

same place.

Figure 7.

Some microscope slides retailed by Amadio. The

green-papered slides are imprinted with Joseph Amadio’s initials, and were

presumably provided to his suppliers by Amadio. The two left-most slides,

‘water beetle’ and ‘bamboo cane’, were made by John Barnett, based on his

distinctive handwriting. The five red slides on the right were made by Charles Topping. Amadio and several other big retailers, such as the Smith and Beck consortia, frequently hid the identities of their suppliers, hence the circular stickers that cover Topping’s name on three of the slides. By preventing customers from knowing the actual makers

of slides and other supplies, retailers such as Amadio could both pretend that

they were the manufacturers and avoid losing customers who might bypass the

middleman by going directly to the makers. The numbers on the Topping slides correspond with numbers in Amadio’s catalogues

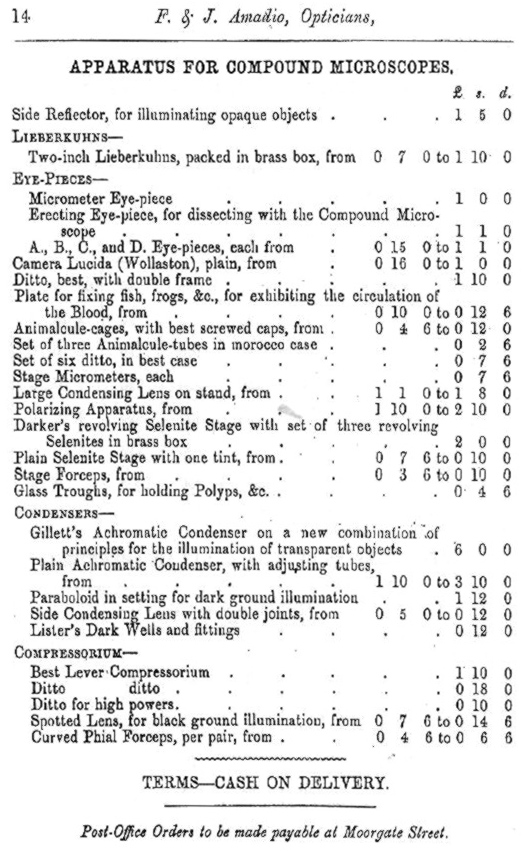

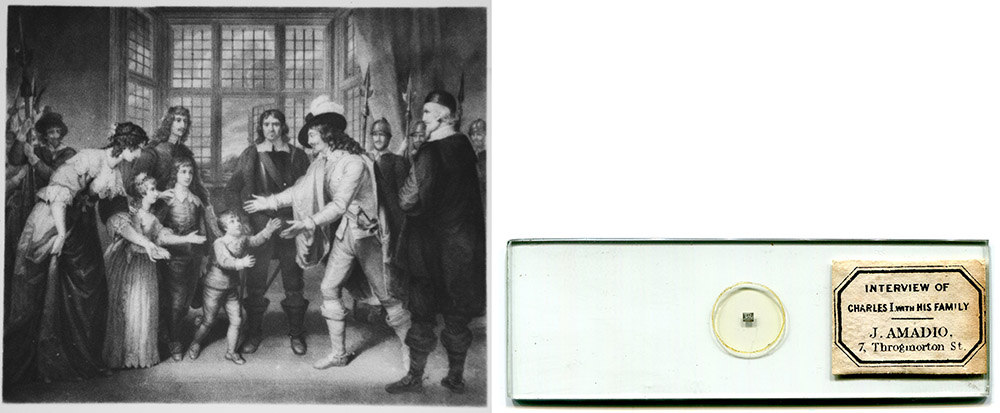

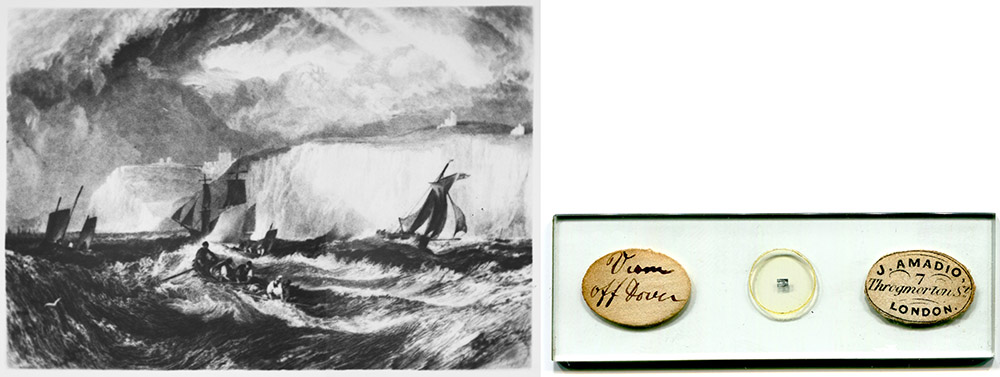

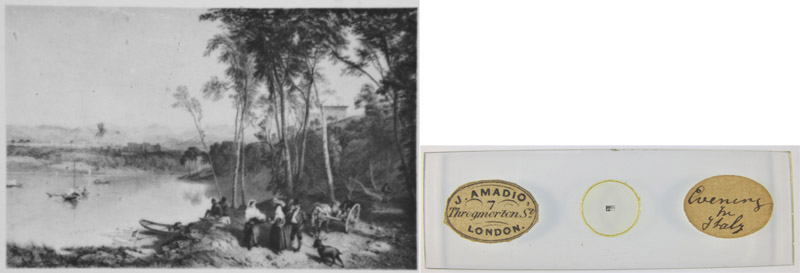

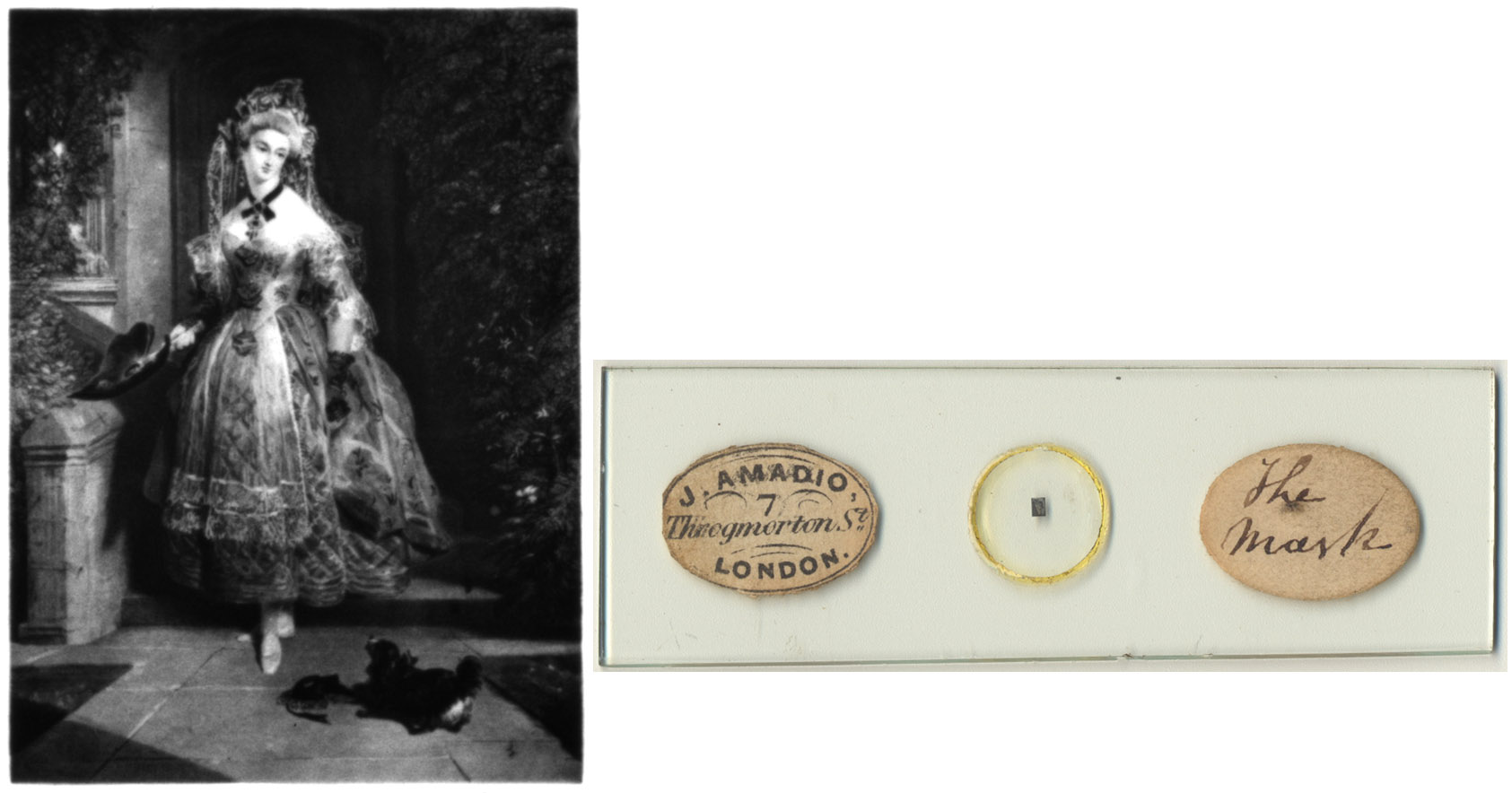

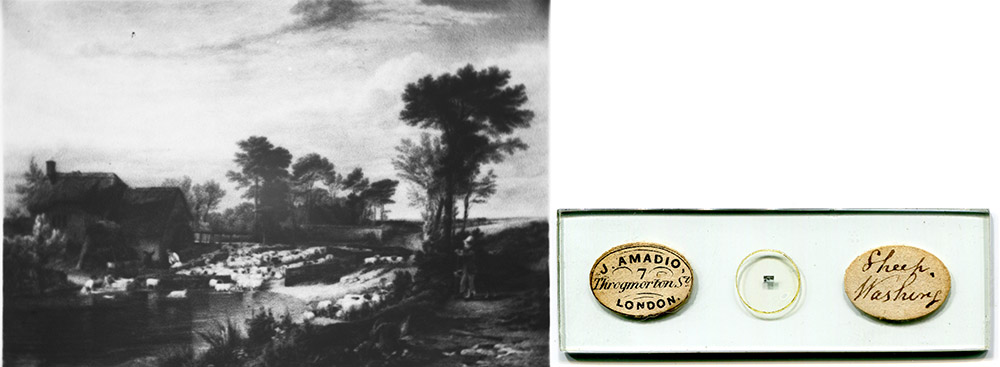

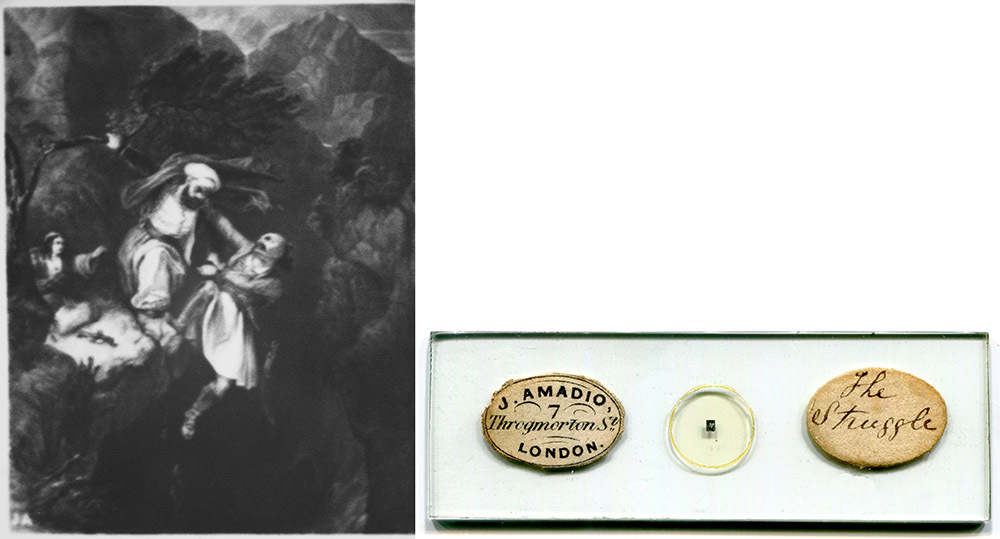

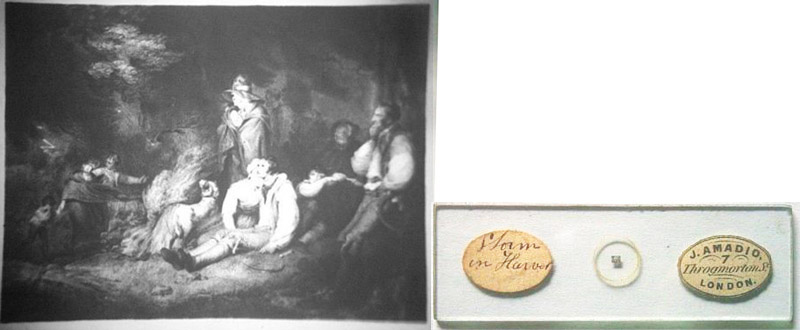

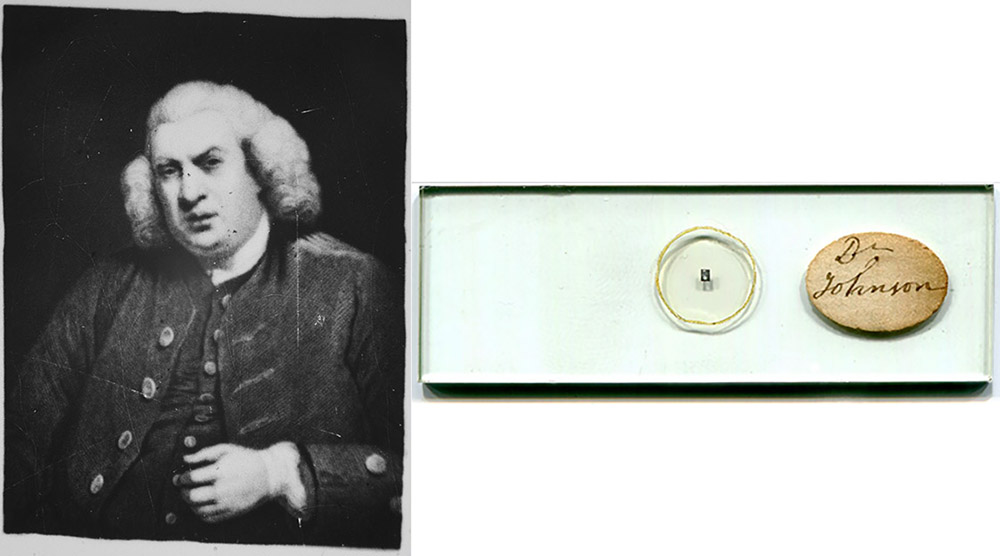

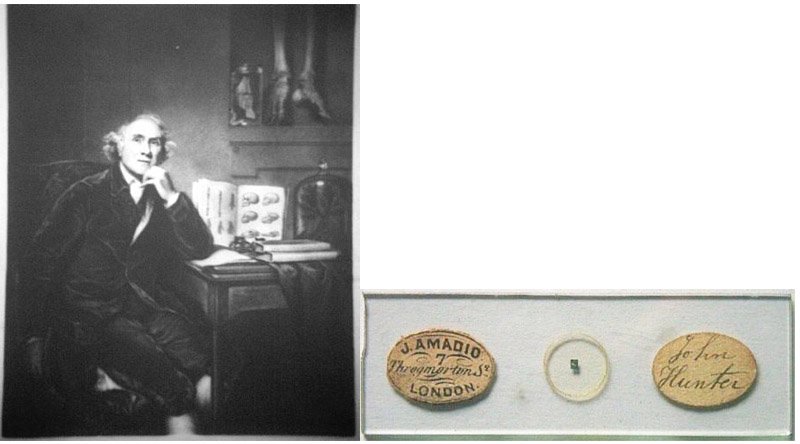

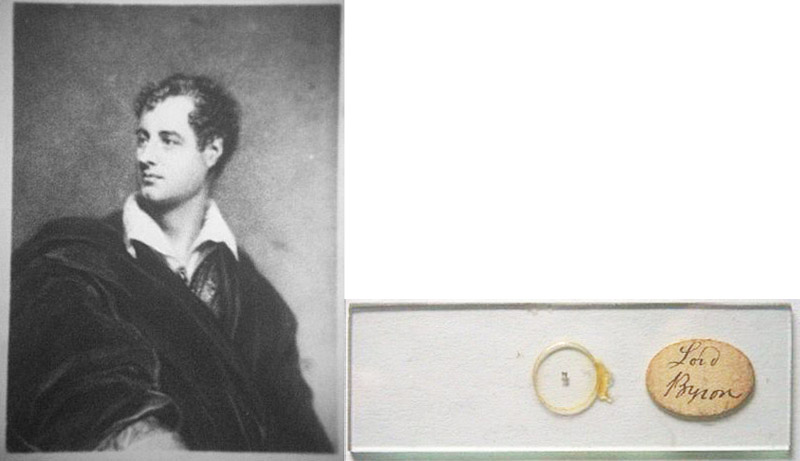

Figure 8.

Microphotograph slides offered by Amadio in 1858.

The vast majority can be attributed to John Benjamin Dancer, and are indicated

in the figure by the letter “D” and the corresponding number in Dancer’s

production lists. Six others, indicated by a green * are microphotographs known to have been produced by

William O. Geller (“W.O.G.”). A seventh slide, “John Hunter”, marked with a red #, was of an engraving by Geller, who probably also made the microphotograph. The

“Testimonial” was an advertising microphotograph, examples of which are shown in Figure 9.

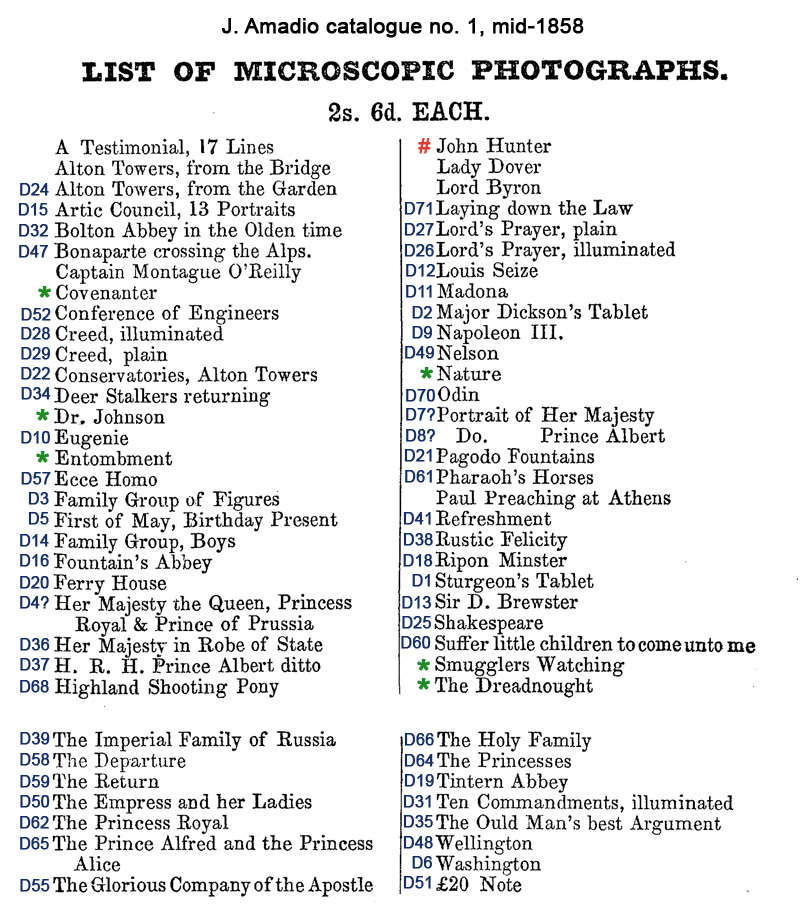

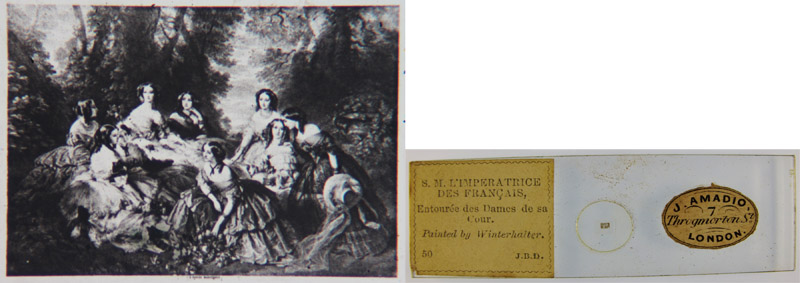

Figure 9A.

“Testimonial” microphotograph slides, sold by Joseph Amadio. (A) An unmagnified view of a Testimonial image. (B and C) Magnified views of Testimonial texts. (D) 1858 print copy of a testimonial microphotograph (see below).

Figure 9B.

Microphotograph of a 5 Pound note, with Joseph Amadio’s signature towards the bottom. The signature indicates that this microphotograph was prepared by or for him. The bank note is dated 17 March, 1859. The image is different from microphotographs known to have been made by other photographers/retailers.

Figure 9C.

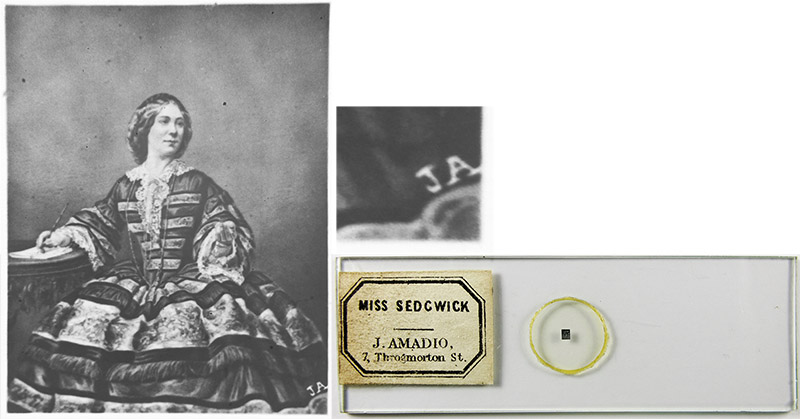

Microphotograph of actress Amy Sedgwick (1835-1897). Joseph Amadio’s initials are fixed into the negative, indicating that this image was made by/for him. The shape of the printed label suggests that it was made for Amadio by William Overend Geller (see below).

Figure 9D.

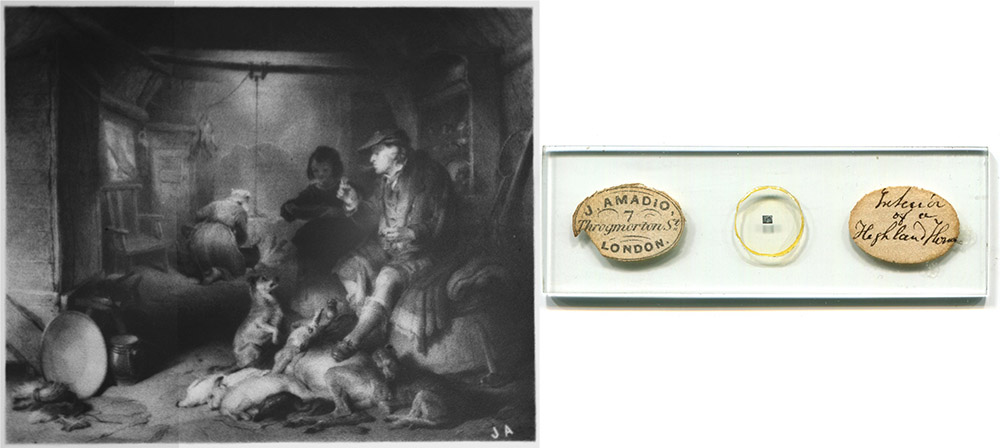

"Interior of a Highland Home", another microphotograph with Joseph Amadio’s initials in the image.

Figure 10.

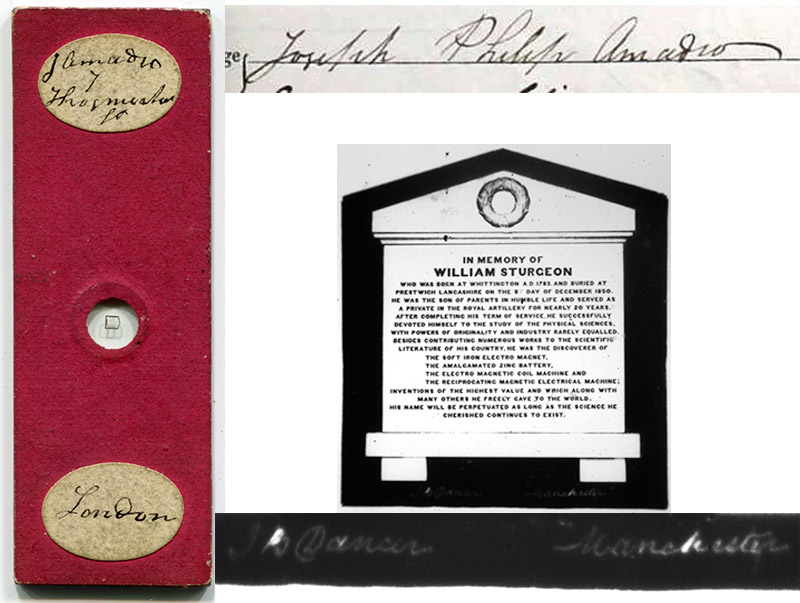

A paper-wrapped J.B. Dancer microphotograph, labeled for sale by J. Amadio. The handwriting on the slide matches Joseph’s signature from his marriage record, shown to the right. Handwriting seen on other Amadio microphotographs also matches Joseph’s handwriting. The image on this slide is "Sturgeon’s Tablet", number 1 in Dancer’s lists, and bears the maker’s signature and address of Manchester within the photograph.

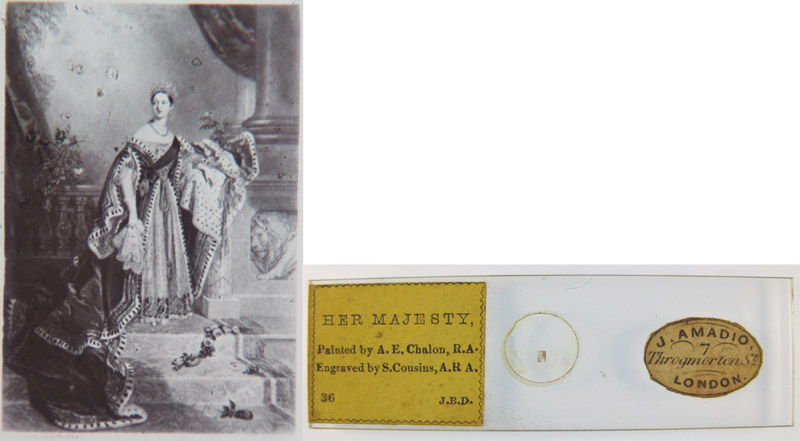

Figure 11.

Two J.B. Dancer microphotograph slides, retailed by

Amadio. Both were included in Amadio’s 1858 catalog. Uncharacteristically,

Amadio did not cover over Dancer’s initials on either slide. That may have been

because Dancer’s reputation might command a higher selling price, or because

Amadio was in London and Dancer was in Manchester, so there was little chance

that Amadio’s customers would go directly to Dancer.

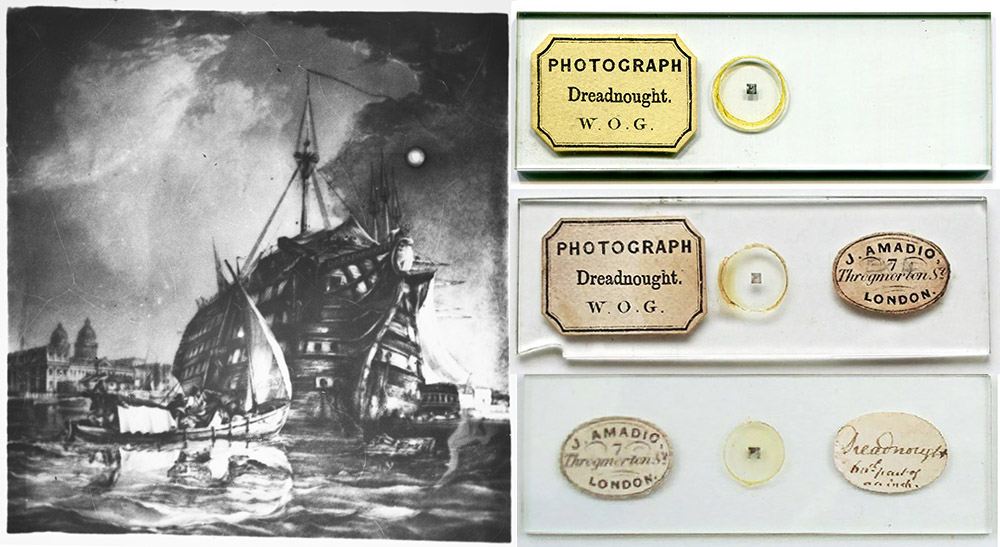

Figure 12.

Microphotograph of the hospital ship “Dreadnought”,

which was listed in Amadio’s 1858 catalog. Evidently produced by

photographer/engraver William Overend Geller, examples of this slide can be found with either Amadio and Geller’s “WOG” labels.

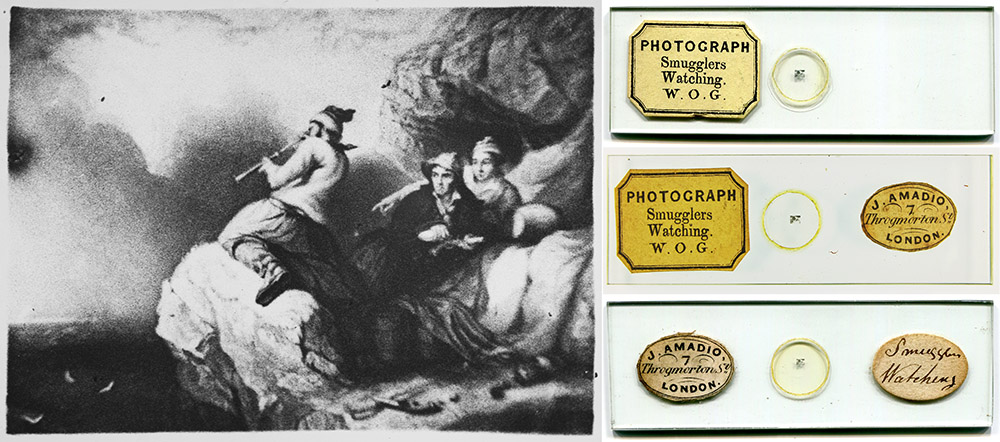

Figure 13.

“Smugglers Watching”, microphotograph produced by W.O. Geller and retailed by Joseph Amadio.

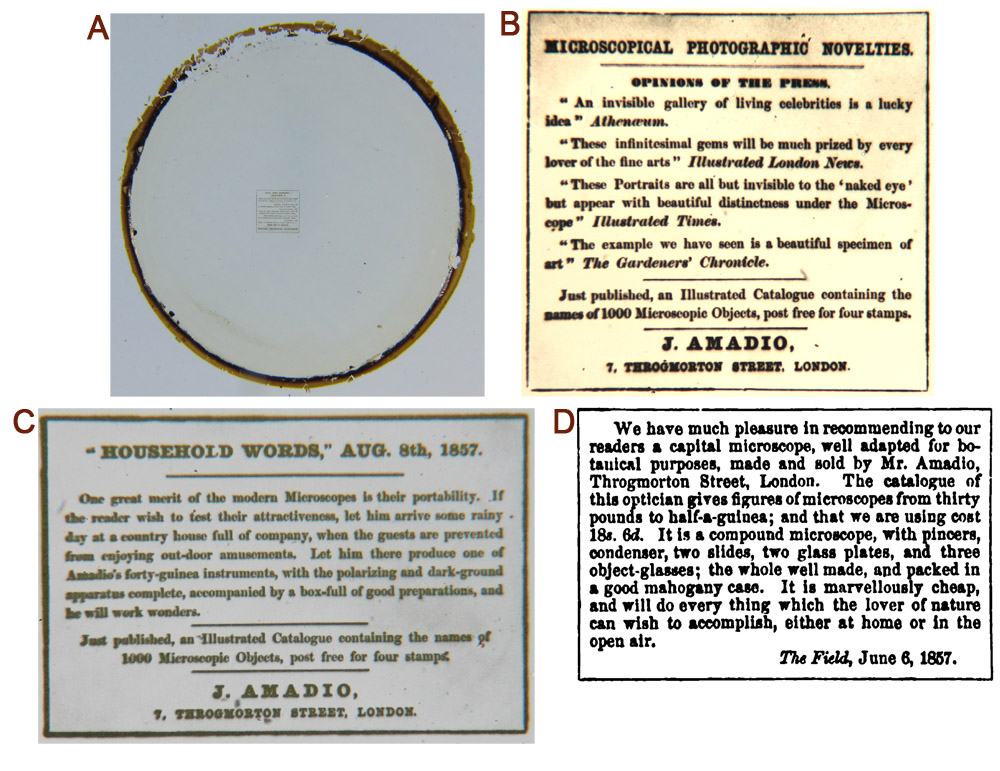

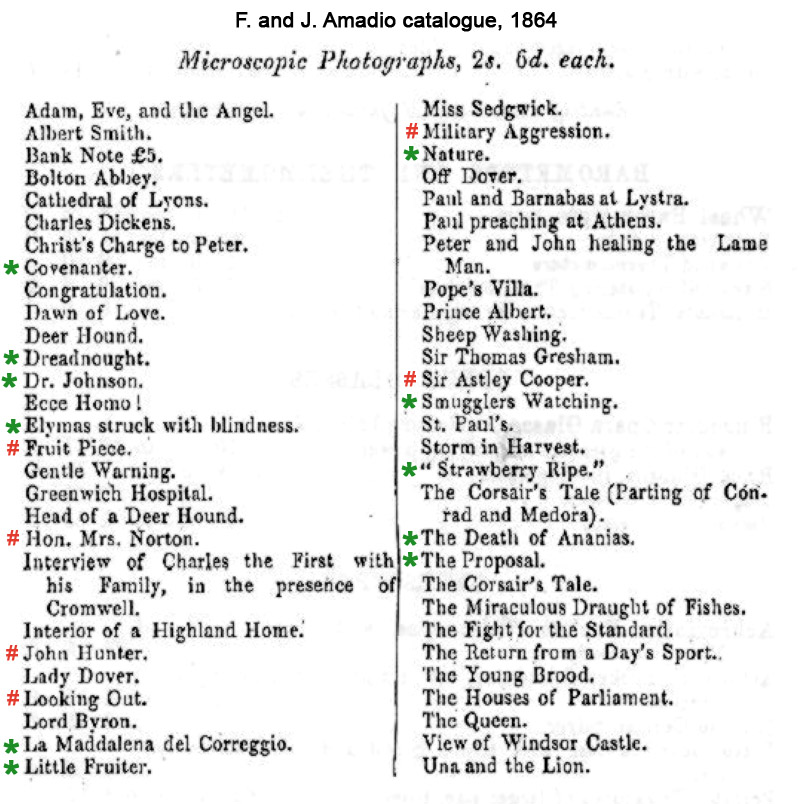

Figure 14.

List of available microphotographs from Amadio’s

1864 catalog. Some may have been supplied by Dancer, although titles that match those of Dancer’s lists of microphotographs were also produced by other photographers. William

Geller (W.O.G.) was a major supplier – titles of his known slides are marked

with a green *,

and those which appear to be photographs of Geller’s artworks are marked with a

red #.

An detailed essay on W.O. Geller’s microphotograph slides and other artwork can also be found on this web site.

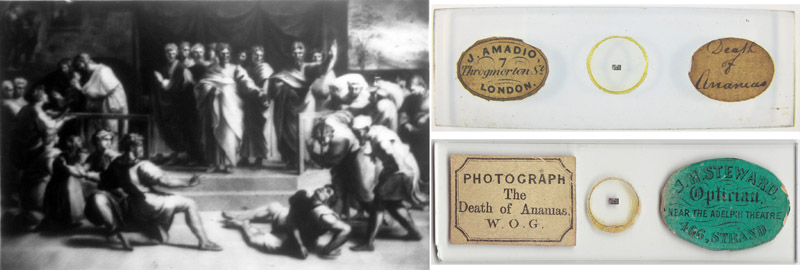

Figure 15.

“Death of Ananias”, microphotograph produced by W.O. Geller. This slide was described in Amadio’s 1864 catalog.

Figure 16.

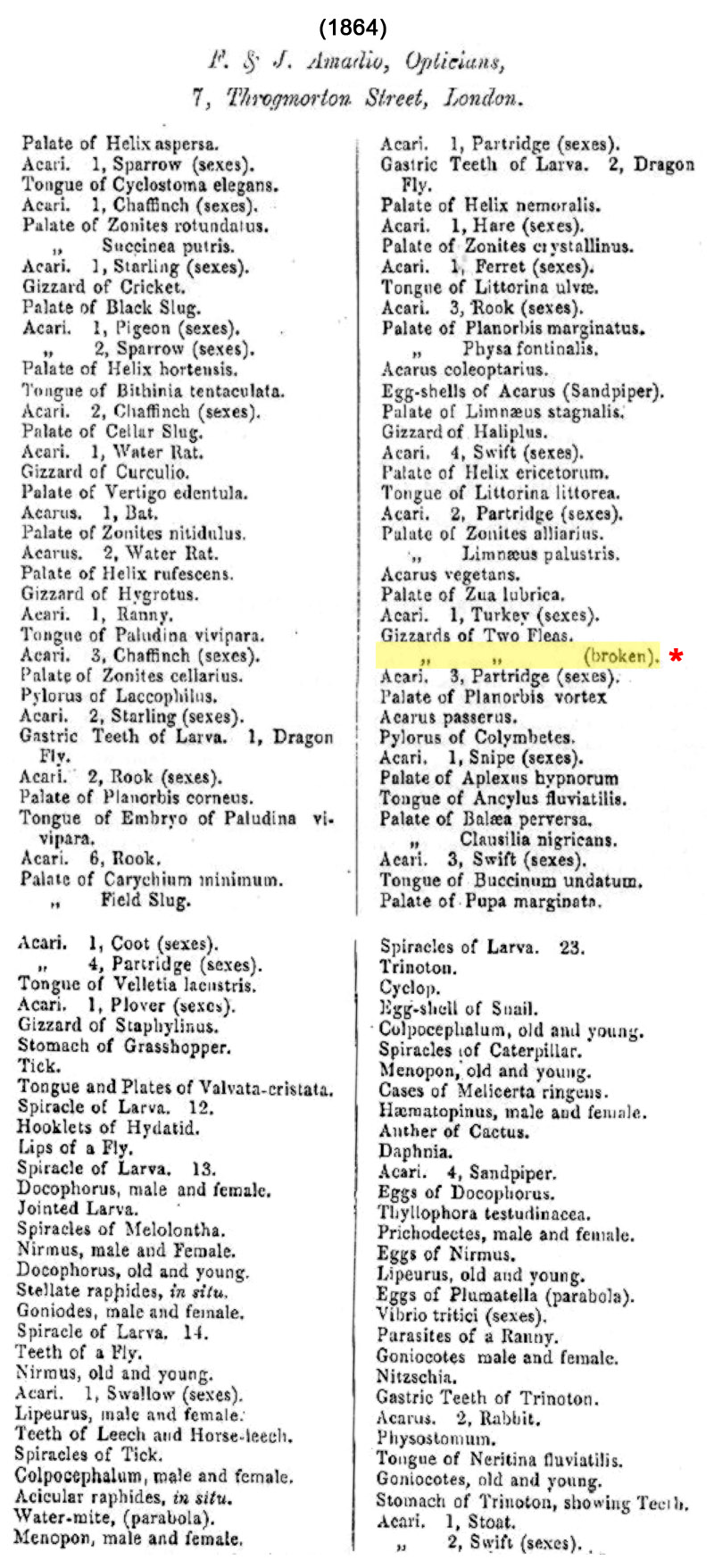

Amadio’s 1864 catalog included this section of slides for sale. The

descriptions match slides such as shown in Figure 17, which are primarily

preparations of parasitic mites (“acari”) and snail palates/tongues/radulae, and almost

always sealed with thick black asphalt. Several features indicate that this

series was a one-off: there is no ordering to the numbers on acari slides (e.g.

number “6 Rook”, but not the preceding numbers), and a broken slide of

“Gizzards of Two Fleas” (highlighted and marked with a red asterisk).

Figure 17.

Microscope slides with specimens corresponding with

Amadio’s 1864 list (see Figure 16). The thick sealant is asphalt, which was

commonly recommended for such a purpose. Other slides by this maker are known,

many bearing dates from the early 1850s (see Figure 18).

Figure 18.

Additional slides by the maker of those shown in

Figure 17, but which do not correspond with Amadio’s catalogs. The three

leftmost slides on the upper row are dated between 1852 and 1854. Those in the

lower row bear labels from Smith, Beck and Beck, of 31 Cornhill. That company

moved to 31 Cornhill in mid-1863, and James Smith retired in 1864, allowing

fairly precise dating of such slides and indicating that their sale was

contemporary with Amadio’s sale of preparations from the same maker. These

features, plus those described in the legend of Figure 16, suggest that these

slides all date from the 1850s, and that large numbers were acquired by Amadio

and Smith, Beck & Beck ca. 1864, possibly due to unloading of a collection

due to its owner’s/maker’s death or other circumstance.

Figure 19.

Three barometers by Joseph Amadio. The dials are

addressed 6 Shorter’s Court (+/- Throgmorton Street).

Joseph Philip Amadio lived his whole life in the area of London, England. He and his family were Church of England, indicating that they were assimilated into English culture. His father, who signed his name as “Francesco”, was born in Switzerland, presumably an Italian canton. The father had lived for many years in England, and Joseph’s mother, Charlotte Seawards, was of old Anglo-Saxon stock. There were at least 6 children: Charlotte, born ca. 1800; Aynesa, born in 1803; Francesco, born in 1805; Angielina, born in 1808; Joseph, born August 22, 1812; and Maria Lucy, born in 1815. Both father and elder son were primarily known in records as “Francis”, and will be referred to by that name for the remainder of this essay. Joseph seems not to have known his birth year, since with every census he gave an age corresponding with birth around 1820. The family appears to have been close-knit: as noted above, Joseph took his brother into his business near the end of Francis Jr.’s life, and Joseph and Maria shared a home for the last years of their lives.

Francis Sr., was described as being an “artificial flower maker” on the 1815 baptism record of daughter Maria, and in an 1818 insurance claim. However, an 1825 insurance claim listed him as a “barometer and thermometer maker”. It is not known where or with whom he learned to make barometers, thermometers and the like. Such a trade required skilful manipulation of glass. The career change came rather late in life, as Francis was probably nearly 40 in 1818. The 1818 claim recorded his address as “2 Islington Road next door to The Coach and Horses”, and the 1825 claim stated “118 St John Street Road (next door to The Coach and Horses)”, suggesting that the address change was due to a renaming/renumbering. An investment record of 1836 listed him as being an “optician”, at 118 St. John Street Road. In those times, “optician” was used to describe all sorts of glass-related trades. The following year’s report on railway investors included “Francesco Amadio, 18, Redcross-st. City, optician” and “Joseph Amadio, 118, St. John-st.-road, optician”. In 1841, Francis Jr. was living on Moorgate Street, with a manservant. The rest of the family has not been located in that year’s census. The next year’s Robson’s London Directory listed four addresses: “Almadio (sic) Frs, barometer mkr, &c. 118 St John st rd”, “Almadio (sic) Frs, optician 118 Redcross st” (was actually #18), “Amadio F. optician, 35 Moorgate st, City”, and “Amadio Josh. optician, 6 Shorters ct, Throgmorton st”. The 1843 Post Office Directory of London listed only three addresses: “Amadio Francesco, sen. optician, 118 St. John streetroad”, “Amadio Francesco, jun. optician, 35 Moorgate street”, and “Amadio John, optician, 6 Shorter’s ct. Throgmorton street”. After Francis Sr. died on June 9, 1843, his probate was signed by “Francesco Amadio, 35 Moorgate Street, Optician” and daughter “Aynesa Amadio, spinster, 118 St John Street”.

Presumably, Shorter’s Court was an alcove or cul-de-sac off Throgmorton Street. Joseph was listed as occupying 6 Shorter’s Court in the 1852 London Post Office Directory of London, while records from 1854 onward list his address as 7 Throgmorton Street. It is not known whether that was due a physical move of his shop, an address renumbering, or reconstruction. Throughout the time of his business at Shorter’s Court / Throgmorton Street, Joseph lived some four miles away at 27 Englefield Road. Living off-premises implies that Amadio’s business was fairly profitable.

A major accident occurred at Amadio’s shop on August 30, 1854. “Shortly before 12 o’clock (in the) morning, an explosion of gas, which created great alarm in the city, occurred on the premise of Mr. Amadio, an optician, in an extensive way of business, at No. 7, Throgmorton-street. Several persons were passing at the time the accident occurred, and one or two sustained injuries. A gentleman named Hamilton was blown with violence against the wall on the opposite side of the way; while another gentleman who was struck down by the shock was, curiously enough, taken into the Dartford gunpowder offices opposite for safety. Mr. Amadio’s shop front was blown out, and his valuable stock in trade was scattered in all directions. It is feared that his loss will be severe. Immediately after the explosion the back of the house took fire, but the enginemen who were quickly on the spot speedily subdued it”.

The destruction of his wares may have prompted Joseph to recast himself as a dealer of the increasingly-popular microscopes and other optical instruments. I have not located any advertisement from before 1855, so do no know what else he sold beyond barometers (and, presumably, thermometers). The 1858 catalog included barometers, but they were at page 28, after microscope slides and eyeglasses. Two advertisements from 1855 indicate J. Amadio’s emphasis that year: “Microscopes – J. Amadio’s Botanical Microscope, packed in mahogany case, with three powers, condenser, forceps, pincers, and two slides, will show the animaculae in water”, and “Race Glasses – J. Amadio’s newly-invented Double Achromatic Field or Sea-side Glass, of such extraordinary power as to be equal to the largest glass made.. Also a powerful Telescope for the waistcoat pocket”. In addition, Amadio sold stereoscope views at this time (Figure 20).

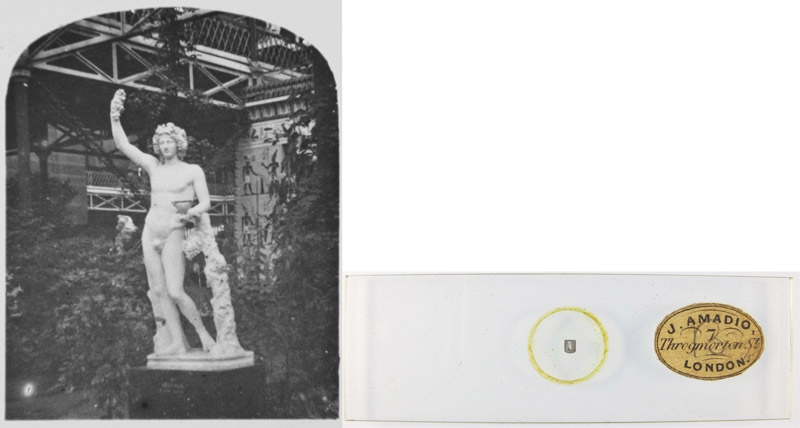

Figure 20.

Glass stereoscope pictures retailed by Joseph Amadio

in 1855. Both are from the Crystal Palace exhibition hall. The top stereoview

is of Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, Napoleon III & Eugenie, photographed

on April 20, 1855, by Philip Henry Delamotte. It is considered to be one of the

first news photographs. Other retailers sold the same stereoview, including

London’s Negretti and Zambra.

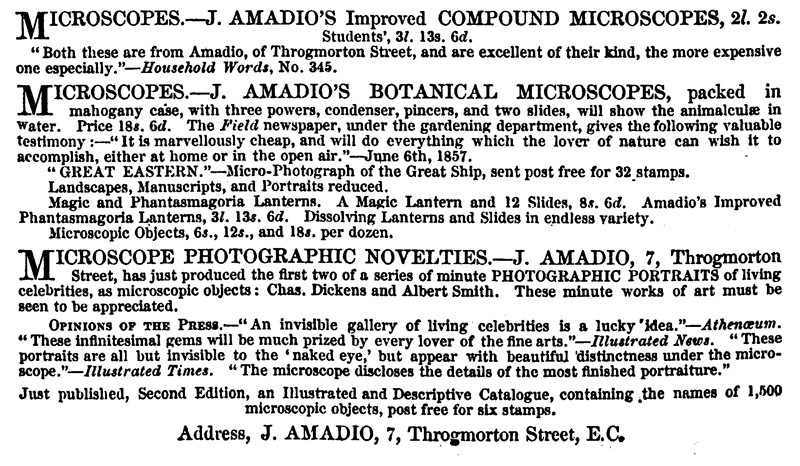

Joseph Amadio appears to have made acquaintance with novelist Charles Dickens, a connection that probably had a strong effect in Amadio’s fortunes. Joseph’s name, microscopes and slides were featured prominently in Dickens’ Household Words and other magazines. Advertisements suggest that Amadio was the first to produce microphotographs with Dickens’ picture (see below).

Dickens’ publicity for Amadio began in November, 1856, with this article from Household Words, “Beginners generally hanker after high powers; but high powers will not show them what they most want to see, as elementary peeps. With a high power you cannot survey the entire portly presence of a male flea, though his stature be smaller than that of his hen. You cannot, with it, haughtily scan from top to toe a parasite from a peacock's plume, or a human head. You cannot, by its aid, admire a miniature flower; such as a flowret from a daisy-club, or a member of a carrot-blossom society, in its complete contour of prettiness. You can only thus look at a fragment, a claw, a tongue, a jaw, a proboscis, an eye, a petal, an anther, or a bit of one. But it is as well to see how things look in their integrity, before you begin to dissect them into morsels. I confess it - my own working instruments (in stricter truth, my implements of recreation) are a humble two-guinea one, principally for opaque objects - of which I almost always use the second power only - and another of not much greater pretensions, costing three guineas and a-half, which is more frequently than not employed (mostly for transparent objects) with a force below its utmost pressure of steam. I keep in reserve a several horsepower of amplification for extraordinary occasions. Both these microscopes are from Amadio, of Throgmorton Street, and are excellent of their kind, the more expensive one especially. Thus, for a sum which has not ruined me, and for which I can proudly show the stamped receipts, I am master of a higher magnifying power than Leeuwenhoek had at his command; notwithstanding which I have considerable doubts whether I shall ever rival his scientific eminence. You will understand that nothing herein premised is contrary to the possibility that I have safe in my closet a hundred-guinea microscope, for Sundays and holidays, unless you are thinking of presenting me with one, to aid my studies; in which case, I beg to withdraw the observation.” (emphasis mine).

Dickens printed a substantial piece on microscopy in 1857, written by Edmund S. Dixon. There are several glowing references in which Amadio is presented as a superior source of microscope slides and equipment, which would have driven substantial numbers of customers to his shop. These are relevant excerpts, “As we treasure cabinet-pictures by Teniers or the Breughels, so shall we set an exalted value on charming bits of still-life from the studios of Amadio or Stevens, on insect-portraits by Topping, on botanical groups by Bourgogne the Elder, and on works by anonymous artists, whose names, though not their productions, still remain unknown to fame…Upon the whole, there is nothing superior to the immense variety of objects supplied, at from fifteen to eighteen shillings per dozen by Amadio, of Throgmorton Street. The sections of wood are very perfect, resembling exquisite crochet-work or lace, and displaying even greater beauty under high powers than under low, which is a test of their excellence. Sponge and gorgonia spicules form another set of lovely minutia? which are different in each respective species of zoophyte. Some are like yellow Hercules' clubs of sugar-candy, which would attract wonderfully in a confectioner's window; others are cut glass billiard-cues intermixed with crystal stars. Objects of unusual rarity, or difficulty or unpleasantness, are dearer everywhere, as it is only reasonable. That charming creature, the itch-insect, - a discourse has been written setting forth the pleasures and advantages of the itch-disease - costs four shillings; the bed-bug is a less expensive luxury, though more so than the ordinary run of objects. In all these, the microscope illustrates the wonders of creation; but there are also preparations wherein the art of man is rendered visible. Upon a small circle of glass is a dim grey spot about the size and shape of the letter U at the beginning of this sentence. To the naked eye, it is unmeaning and indistinct. Viewed with a sufficient power, it displays a mural monument, on the face of which is an inscription, in nineteen lines of capital letters, ‘In Memory of William Sturgeon’ - with a longer biographical notice than I have room for here, and all within considerably less than the limits of this letter U. It is not, as might be supposed, the manual result of patient toil and eye-straining; nor is the feat accomplished by clever mechanical arrangements; it is an application of the photographic art. Not only are microscopic photographs taken from fixed and inanimate objects, like the above mural monument, but also from living personages, and even groups from life. First, an ordinary photograph is taken, say four and a-quarter inches, by three and a-quarter. The picture so obtained is gradually reduced by using lenses of a short focal length. When an engraving or a monumental tablet has to be reduced, the photographic picture may be taken much smaller in the first instance; but when a group of figures from life or an individual portrait is required, a lens of comparatively greater focal length must be used. It is impossible to get from life, a very small picture at the first step; because the various portions of the group would not all be distinctly in the focus. Microscopic photographs are sold at four and sixpence each. Loyal or loving persons can thus carry about with them, at a cheap rate, the portrait of their sovereign or their sweetheart, packed in the smallest possible compass. By similar means, secret correspondence can be carried on. A microscopic message photographed on glass, might pass through a multitude of hostile hands, without its import being even suspected. Timid suitors might save their blushes by the presentation of a petition to be perused, not under the rose, but under the microscope ... One great merit of modern microscopes is their portability; if the reader wish to test their attractiveness, let him arrive some rainy day at a country house full of company, when the guests are prevented from enjoying out-door amusements. Let him there produce one of Amadio's forty-guinea instruments, with the polarizing and dark-ground apparatus complete, accompanied by a boxfull of good preparations, and he will work wonders.” (emphasis mine).

Amadio’s most expensive microscope cost £27 in 1858 (the Guinea was not an official unit of currency in 1857, but was considered to be essentially equal to one Pound). Dixon’s description of the desirable 40 Guinea microscope may have been a coordinated reverse bait-and-switch, propelling customers into Amadio’s shop with the expectation that they “needed” a 40 Guinea microscope, who would then be relieved to find that it cost “only” 27 Pounds.

The microphotograph described as “In Memory of William Sturgeon” was Sturgeon’s Tablet, the first slide issued by J.B. Dancer. It is one of the many Dancer slides described in Amadio’s 1858 catalog (see Figures 8, 10 and 11, above).

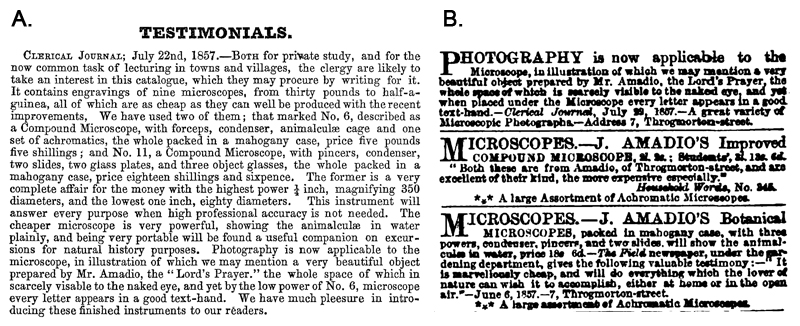

Another strong endorsement was published in the July 22, 1857 Clerical Journal. This was reprinted in Amadio’s first catalog (Figure 21A), and excerpts used in advertisements for many years to come. The catalog version creates confusion on the catalog’s date of issue. I have not yet located a copy of the original Clerical Journal article. However, an Amadio advertisement from September, 1857 indicates that the he was not above altering quotations (Figure 21B). Other advertisements indicate that the first catalog was issued during the autumn of 1858 (Figure 22).

Figure 21.

Amadio changed “testimonials” to suit his advertising needs.

(A) From Amadio’s first catalog.

(B) Advertisement in the September 12, 1857 issue of ‘The Athenaeum’. The “quote” included in his first catalog states “yet by the

low power of No. 6, microscope every letter appears”, while the advertisement

states, “yet when placed under the microscope every letter appears”. The

extensive details of his microscopes in the “testimonial” also give the

impression of a self-crafted promotion rather than a second-party

recommendation. These call into question the implication that Amadio’s catalog

was available in July, 1857. All other sources indicate that it was actually

produced in October, 1858 (see Figure 22). Note also that the September, 1857

advertisement states that Amadio prepared the described microphotograph, when

it was undoubtedly produced by J.B. Dancer or another outside source (see

Figures 8 and 23).

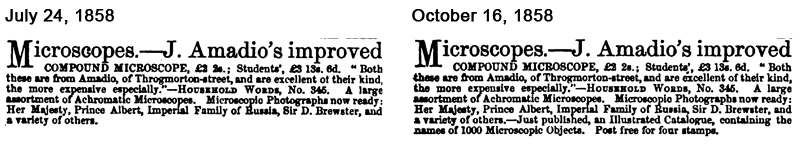

Figure 22.

Advertisements from ‘The Lancet’ that help date

Amadio’s first catalog.

(A) This

July, 1858, advertisement names several “microscopic photographs now ready”,

all of which were included in Amadio’s catalog (Figure 8). Previous

advertisements mentioned only the Lord’s Prayer microphotograph that was noted

in 1857 (Figure 21).

(B) This

October advertisement declares, “Just published, an Illustrated Catalogue.” No

previous advertisement mentioned a catalog. Hence, it can be concluded that

Joseph Amadio issued his catalog around the beginning of October, 1858.

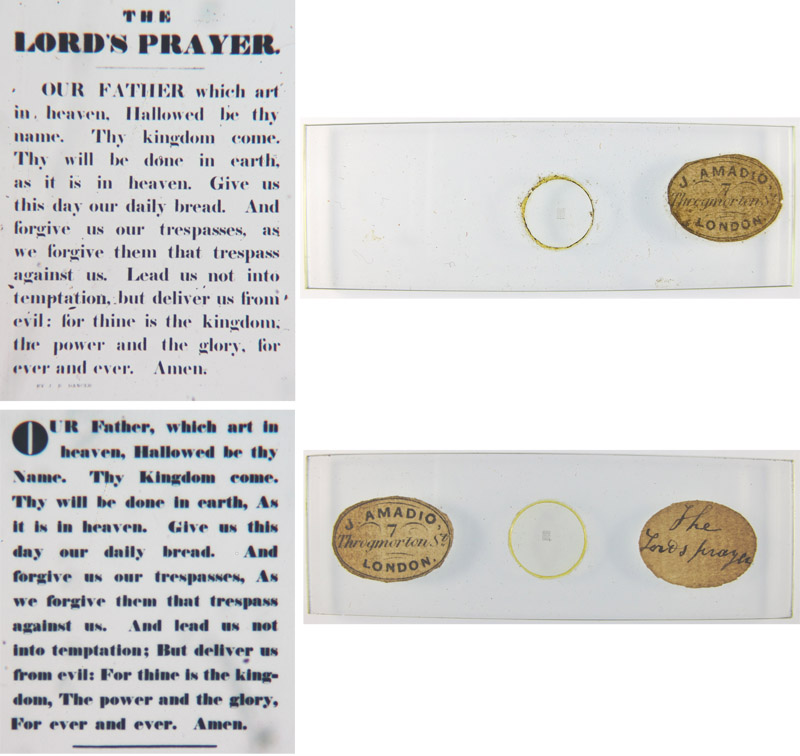

Figure 23.

Two versions of the Lord’s Prayer, both sold by

Joseph Amadio. The upper photograph includes J.B. Dancer’s name in the lower left

corner. The lower photograph is not signed.

There were numerous, extensive published descriptions of Amadio’s microphotograph slides, suggesting that he was a significant source of those novelties to the London market. Some examples follow:

The Athenaeum, November 6, 1858, “An invisible gallery of living celebrities is a lucky idea. Mr. Amadio, of Throgmorton Street, must be a fine humourist. A series of heads not so large as pins’ points is given to the public, we infer, by way of satirical commentary on the rage which seems to possess well-meaning folks for distinguished contemporaries, men of the time, living celebrities, and the like - in books and prints, in paint and crayon. Mr. Amadio’s series will be on glass; the first number is said (in a note charitably forwarded with this specimen) to be a portrait of the Author of ‘Nicholas Nickleby’; but having no microscope on our reading-desk we are unable to say whether this be a true description. Critics as we are, trained to the discovery of minute as well as large beauties in an author, we cannot find in the speck of dirty white on this glass a single trace of our humorous and sagacious friend.”

The National Magazine, 1858

(the inscription of the described microphotograph is also shown in Figure 9, above),

“The Invisible Paragraph. .. I .. have

faith in some things which I do not see at the first glance immediately. The

other day there reached me by post, prepaid, a leather spectacle-case. But I

don't use spectacles yet, seeing better without than with them at present. The

case contained an oblong slip of glass. In the middle of that slip was cemented

a circular transparent film; and in the middle of the circle was a small,

oblong, faint-gray spot, of such a length and breadth that it would be quite covered,

with perhaps a little bit of counterpane to spare, by the letter m of the type in which this is

printed. What was the use of sending me that? - a thing like a flyspot squared

to rectangular form

But - I am not ashamed to confess it - I pick up a

good many crumbs of information from the periodicals of the day; and in one of

the esteemed contemporaries of the National Magazine I had read, under the

heading of ‘Microscopic Preparations,’ that, although the microscope mainly

illustrates the wonders of creation, there are also preparations wherein the

art of man is rendered visible. Upon a dim spot about the size and shape of the

letter U at the beginning of this sentence, - a spot which to the naked eye is

unmeaning and indistinct, - we are told that we can discern, under a sufficient

magnifying power, a mural monument, on the face of which is an inscription, in

nineteen lines of capital letters, ‘In Memory of William Sturgeon’, with a

longer biographical notice than there is room to copy here, and all within

considerably less space than the limits of this insignificant letter U. It is

not, as might be supposed, the manual result of patient toil and eye-straining;

nor is the feat accomplished by clever mechanical arrangements; it is an

application of the photographic art. Not only are microscopic photographs taken

from fixed and inanimate objects, like the above mural monument, but also

portraits of living personages, and even groups from life.

How these incomprehensible results are effected,

there are Manchester people who can tell you, if they will; all I know is, that

microscopic photographs are sold in London at four-and-sixpence each.

‘Four-and-sixpence’, utilitarians will exclaim, ‘for a speck of soiled film,

which you may put in your eye and see none the worse!’ - which is very

convenient, as well as very cheap. For loyal or loving persons can thus carry

about with them, at a reasonable rate, the portrait of their sovereign, or

their sweetheart, packed in the smallest possible compass. By similar means, secret

correspondence can be carried on. A microscopic message thus photographed on a

little bit of broken glass might stand the scrutiny of a multitude of hostile

eyes without its import being even suspected. It would be less significant, as

well as more portable, than the symbolic cakes and lotuses which the diabolical

sepoys passed from hand to hand previous to their orgies of crime and blood.

Timid suitors, again, might save their blushes by the presentation of a

petition to be perused, not under the rose, but under the microscope.

A word to the wise and a clue to the curious inquirer

ought to suffice for any but a donkey. Evidently the contents of my

spectacle-case are meant, not to be looked with, but to be looked at. Let us try. Out with the microscope.

What a pleasing moment is that when we feel ourselves

on the point of discovering something new! We are almost tempted to dally with

the secret in our power, and to prolong the delightful suspense, before we take

the final step which shall convert the unknown into the known, which shall

change anticipation into possession. That little morsel of grayish dirt will

reveal itself - as what? Metamorphose me into a Hindo woman-slayer, if it is

not a quotation from a London paper - a paragraph from a respected follow

journalist. But instead of being reproduced in print, it has been transcribed

into handwriting, - perhaps that of its author, - and neatly enclosed by a

single circumscribing line drawn around it. For the edification of the

lookers-on, who will not believe that the dirt-spot is any thing but a spot of

dirt, I read aloud as follows before allowing them to read in turn:

We have much pleasure in recommending to our readers

a capital microscope, well adapted for botanical purposes, made and sold by Mr.

Amadio, Throgmorton Street, London. The catalogue of this optician gives

figures of microscopes from thirty pounds to half-a-guinea; and that we are

using cost 18s. 6d. It is a compound microscope, with pincers, condenser, two

slides, two glass plates, and three object-glasses; the whole well made, and

packed in a good mahogany case. It is marvellously cheap, and will do every

thing which the lover of nature can wish to accomplish, either at home or in

the open air.

June 8, 1857.

What say you now to the invisible paragraph? Is it not a clever application of microscopic photography? Is there not considerable adroitness in putting a laudatory notice of a microscope into a shape which is at first sight imperceptible? .. when you don't look at it - with the microscope - it isn't there; when you do so look at it, it is”.

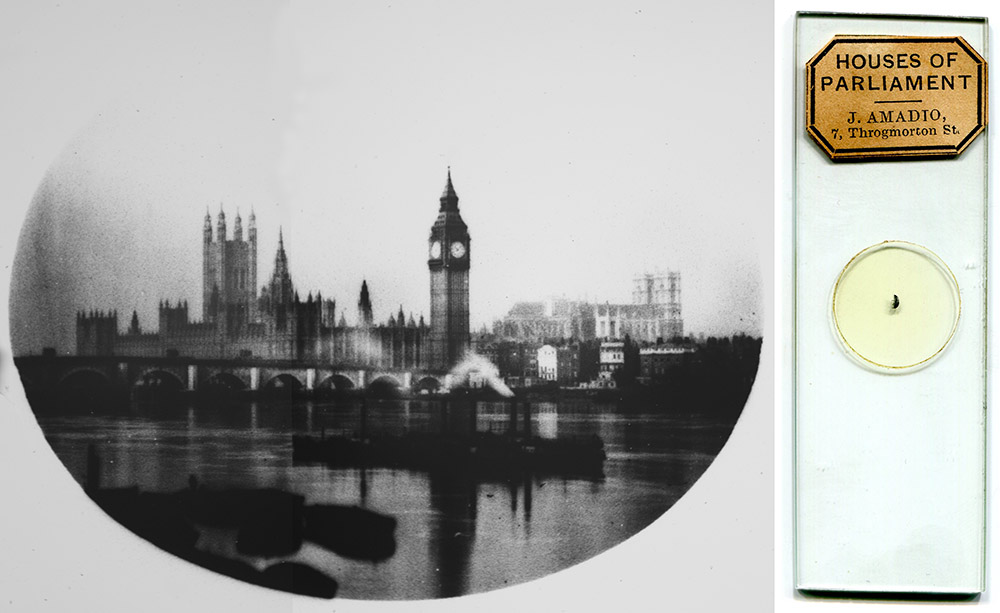

The Spectator, February 26, 1859, “Mr. Amadio continues his progress in reducing the scale of microscopic photographs. We have this week seen two that excel any specimens hitherto brought under our notice. One, which to the naked eye looks like a mere speck on the glass, the minute trace of some stain, under the microscope becomes a beautiful landscape picture - a clear and distinct view of the Houses of Parliament, with Westminster Bridge, the Abbey in the distance, two steam-boats, and several barges. It is, however, not simply the minuteness of the picture which is so remarkable, but its finish and breadth. The architecture, the aerial perspective, the soft but brilliant and well balanced distinction between the shine upon the water and the shade, are brought out with equal force and finish. To the naked eye the other specimen is an exceedingly small circular speck, such as might be left if the glass were touched with a damp pin's head, the pin being by no means large; under the microscope, this develops itself into a beautiful portrait, such as might have been painted by Guercino, being the head of a youth, Mr. J.E. Pedder, an Eton scholar, the son of Mr. Pedder, of Preston Park in Lancashire. By the help of this microscopic photography a single locket becomes a picture gallery of family affection or history”.

The Living Age, April 30, 1859, “Microscopic Photographs. We have been favored with an inspection of some marvellously beautiful specimens of microscopic photography taken by Mr. J. Amadio, whose excellent compound microscopes are now so favorably known in the scientific, and especially in the botanical world. The portraits of living celebrities, such as Mr. Charles Dickens, Mr. Albert Smith, and Miss Sedgwick, have already earned their due need of admiration; but the most exquisite specimen yet produced is a portrait of a youth which occupies the infinitesimally minute space of the two-hundredth part of an inch. To say that this Lilliputian picture is as large to the naked eye as a pin’s head would be an exaggeration ; for surely no pin was ever made whose head could equal this in minuteness. A pin’s point would probably be much nearer the truth. Of course nothing can be made of them by the unassisted vision; but when submitted to one of Mr. Amadio’s common pocket microscopes every feature comes out with wonderful sharpness and distinctness, and we behold a perfect portrait. Under a microscope of higher power, the effect is naturally very much better. Another beautiful specimen is a view of the Thames at Westminster, including the Houses of Parliament, Westminster Abbey. etc. To the eye this appears more like a preparation of some minute insect than any thing else, the river and ground view doing duty for the body, and the spires and turrets for the legs of the animal; but under the microscope it comes out with astonishing distinctness, every architectural detail being most accurately marked”.

An advertisement in the April 9, 1859 issue of The Law Times included this testimonial, “Microscopic Photographic Curiosities – Mr. Amadio of Throgmorton-street, whose portrait of Mr. Charles Dickens no larger than a pin's point, we lately noticed, has produced by photography a view of Westminster-bridge with the Houses of Parliament and Westminster Abbey, within a space not larger than the eye of a worsted needle. Although the elements of the landscape cannot be distinguished by the naked eye, under a microscope of ordinary power, the photograph represents a broad view, in which every feature is plainly brought out, from the barges in the river and the foliage of the houses in Whitehall-gardens to the Westminster churches in the background. Two river steamboats lie at the pier, and their steam as it is impetuously discharged from the funnel, and dies off in wreaths in front of the bridge, is shown with all the accuracy of a large photograph. The same gentleman has published a portrait of a youth, which is only just larger than a needle‘s point, but when magnified is as perfect as any conceivable likeness.-Daily News, March 10th”.

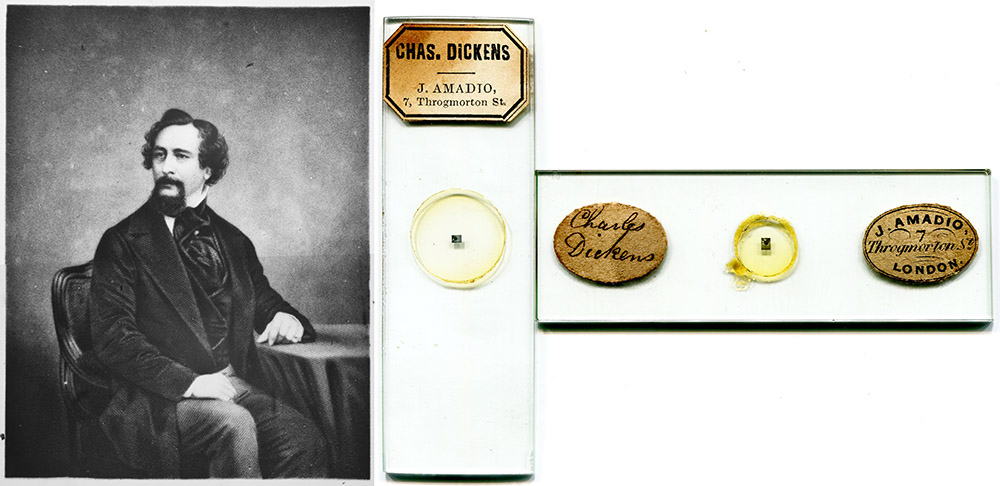

Figure 24.

Two of the Amadio microphotographs that received significant discussion in the press during 1858-59, “Charles Dickens” and “Houses of Parliament”. The Dickens microphotograph is not the same as that

issued by Dancer, implying that this slide was produced by another photographer.

The manifold published descriptions of Joseph Amadio’s wonderful microphotographs raised hackles in Manchester, the home of microphotography’s inventor, John B. Dancer. The irony is that, in the late 1850s, many of Amadio’s microphotograph slides were made by Dancer. From the minutes of the March 22, 1859 Ordinary Meeting of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society, “Mr. Binney made the following statement. In the public prints, frequent allusions are made to micro-photography. In the Manchester Guardian of the 11th March instant, is the following paragraph: ‘Photographic curiosities - M. Amadio of Throgmorton-street, whose portrait of Charles Dickens no larger than a pin’s point was lately noticed, has produced by photography a view of Westminster Bridge, the Houses of Parliament, and Westminster Abbey, within a space not larger than the eye of a worsted needle. The same gentleman has published a portrait of a youth which is only just larger than a needle’s point, but, when magnified is as perfect as any conceivable likeness’. No doubt most of the members of this society have seen the beautiful specimens of micro-photographic art produced by one of our fellow-members, Mr. J.B. Dancer, F.R.A.S., during the last five years. So early as the year 1840 Mr. Dancer began his investigations on the subject, and soon produced satisfactory results on silver plates. In May, 1853, when Dr. Joule, F.R.S., and some other friends erected a tablet to the memory of our late distinguished member, Mr. Wm. Sturgeon, the electrician, Mr. Dancer was so kind as to present me with a photograph of the tablet not larger than a pin’s head. His discovery was not allowed to rest, for hundreds of his beautiful specimens were sent all over the world. Within the last year or two, several parties have coolly claimed Mr. Dancer’s discovery, and when it is represented in a local print as something wonderful in M. Amadio having produced what Mr. Dancer did six years ago, it is only due to our fellow-member and townsman to set the public right as to who was the real discoverer of micro-photography.”

Figure 25.

Amadio advertisement, from the January, 1860 issue

of ‘The Cornhill Magazine”. Note that the second edition of Amadio’s catalog

had just been published.

Positive descriptions in the press continued. The Reverend James Dalton wrote in an 1860 Magazine of Natural History and Naturalist, “Mosses have of late become more popular amongst botanists. Wilson's ‘Bryologia Britannica’ is a miracle of scientific knowledge, accurate research, and unwearied industry. It would be strange if such a book did not act as a spur to those who are able to appreciate the beautiful plants of which it treats. The number of ‘Bryologists’, has accordingly increased of late years, and we may apply to their studies what the "Guide to Etiquette" predicates of almsgiving: ‘It has of late grown fashionable, and indeed is worthy of recommendation on its own account’. By drying a moss without pressure you may lay it by for any length of time to examine on a rainy day, when it has been relaxed by a little warm water. A large collection packs into a small compass, and specimens for exchange are transmitted by post with the greatest facility. The necessary apparatus is simple and inexpensive, (and if thou, good reader, art looking for an annual stipend of £46, this will be a consideration.) True, the Bryologia Britannica costs two guineas, but as it would be difficult to name any information on the subject of which it treats, that is not contained therein, no other book will be required. A small pocket microscope suffices for most purposes. One of Amadio's at eighteen shillings or a guinea, answers admirably for determining species”. The 18 shilling or 1 guinea microscopes were simple drum instruments, as illustrated in Figure 4.

All the Year Round, another Dickens publication, carried this in 1862, “Flies do not breathe, like men, through the mouth, but through a set of holes in the abdomen, called stigmata or spiracles. By these, the air passes into beautifully constructed tubes, called tracheae, or wind-pipes. The spiracles are furnished with a curious contrivance to prevent dust from entering. The hole is closed by a sort of sieve or screen, which must be seen to be appreciated. A drawing gives you some idea of its nature, but the real thing is far better; and as not every one is up to such minute manipulation, recourse should be had to microscopic preparations, which are furnished at a reasonable rate by Amadio of Throgmorton-street, London, and other first-rate opticians”.

Figure 26.

A Joseph Amadio “Student Box” of microscope slides.

In 1860, he advertised it as “containing Six Dozen beautiful Specimens in

polished Mahogany Box, fitted

with racks, brass lock and key, &c. produced under J. Amadio’s immediate

superintendence, especially adapted for the Student”.

Advertisements as late as 1862 listed the microscopy business as being that of “J. Amadio”. The 1863 Goldsmiths', Jewellers', Silversmiths', Watchmakers', Opticians', and Cutlers’ Directory listed Joseph and Francis separately, “Barometer and Thermometer Manufacturers .. Amadio F., 5 Birchin-lane, E.C.” and “Wholesale, Manufacturing and Working Opticians .. Amadio, F., 5 Birchin-lane, City; Amadio, JP, 7 Throgmorton-street”. The 1864, third edition of Amadio’s catalog listed the shop as “F. and J. Amadio”.

Francis died on March 4, 1866. He had never married, and all census records have him living alone, with only a single servant. Intriguingly, one of their unmarried sisters, Aynesa, died less than two weeks after Francisco. Both left a modest estate to sister Maria, also unmarried, with whom Aynesa had been living.

By that autumn, Joseph had reverted the business name, and had moved from Throgmorton Street to 17A Telegraph Street, Moorgate Street (Figure 27). This was a different location than Francisco’s old shop.

Figure 27.

Advertisement from the October 6, 1866, ‘London Daily News’.

Figure 28.

The last identified advertisement from Joseph Amadio, March, 1869. Note that this advertisement still highlighted testimonials from the 1850s.

The remainder of Joseph Amadio’s life is a bit of a mystery. His last identified advertisements date from early 1869 (Figure 28). He has not been conclusively identified in either the 1871 or 1881 census. His wife, Emma, died in late 1886, in the Chelsea area of London. There are no records of Joseph and Emma having had children. The 1891 census recorded Joseph, his unmarried sister Maria, and a servant girl, living at 3 Sutton Lane, Chiswick, Middlesex (London). Joseph was listed as “retired optician”, and Maria was “living on own means”. Next door, lived the Pastorelli family of instrument makers: Francis Pastorelli (“retired optician”), Alfred Pastorelli (“meteorological instrument maker, optician”) and Ralph Pastorelli (“aneroid maker optician”).

Joseph and Maria Amadio died on the same day, January 24, 1892. Each left an estate in excess of £4000. Joseph’s probate was processed twice, once in 1892 and again in 1893: “Amadio Joseph Philip of 3 Grosvenor Villas Sutton Lane Chiswick Middlesex gentleman died 24 January 1892 Administration (Limited) London 13 May to Edward Holroyd Boustfield auctioneer Effects £4168 6s 6d. This grant has ceased Administration (with Will) August 1893”, superseded by “Amadio Joseph Philip of 3 Grosvenor-villa Sutton-lane Chiswick Middlesex gentleman died 24 January 1892 Administration (with Will) London 5 August to Francis John Pastorelli gentleman Effects £4168 6s 6 1/2d. Former grant May 1892”.

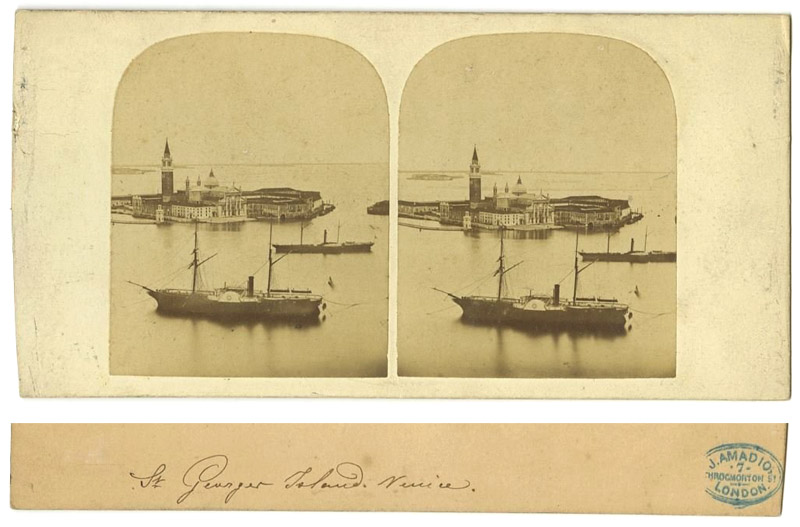

Figure 29.

A paper stereoview of Georges Island, Venice,

stamped on the reverse as having been sold by J. Amadio.

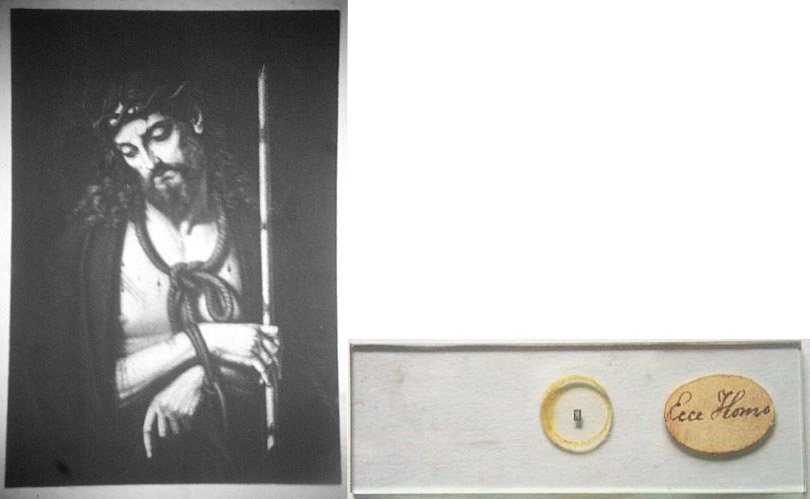

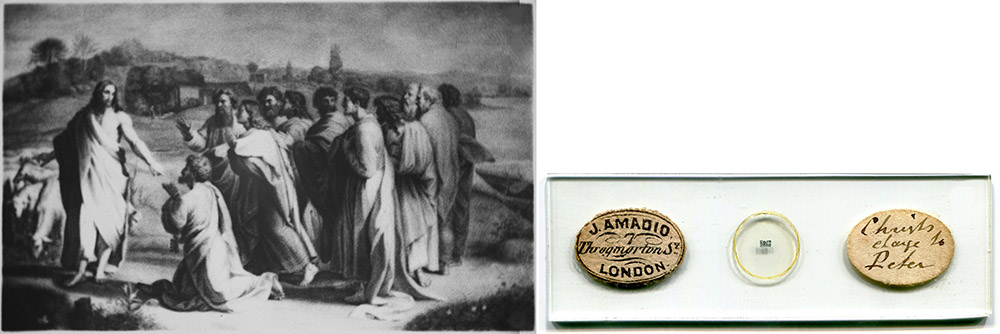

Figure 30.

Additional microphotographs that were sold by Joseph Amadio.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Richard Courtiour, Peter Hodds and anonymous collectors for providing images of Amadio slides and equipment, and to Baldwin Hamey for additional information on the Amadio family.

Resources

All the Year Round (1862) Flies, Vol. 8, page 8

Amadio, Joseph (1858) A Catalogue of Achromatic Microscopes and other Optical, Philosophical, and Mathematical Instruments, Manufactured and Sold by J. Amadio, Optician to the Admiralty, 7, Throgmorton Street, London

Amadio, Francis and Joseph Amadio (1864) A Catalogue of Achromatic Microscopes and other Optical, Philosophical, and Mathematical Instruments, Manufactured and Sold by F. & J. Amadio, Opticians to the Admiralty, 7, Throgmorton Street, London

The Art Journal (1859) Advertisement from J. Amadio, Vol. 8, April issue

The Athenaeum (1857) Advertisements from J. Amadio, Vol. 1, pages 986 and 1130

The Athenaeum (1858) Our weekly gossip, Vol. 2, page 589

The Athenaeum (1860) Advertisements from J. Amadio, Feb. 11, page 217; April 21, page 558; and Aug. 4, page 173

The Athenaeum (1861) Advertisements from J. Amadio, January, page 62

Baptism record of Angielia Amadio (1808) Parish records of St. Mary Lambeth, accessed through ancestry.co.uk

Baptism record of Aynesa Amadio (1803) Parish records of St. George Bloomsbury, accessed through ancestry.co.uk

Baptism record of Francesco Amadio Jr. (1805) Parish records of St. Giles in the Fields, accessed through ancestry.co.uk

Baptism record of Joseph Philip Amadio (1812) Parish records of St. George Bloomsbury, accessed through ancestry.co.uk

Baptism record of Maria Lucy Amadio (1815) Parish records of St. Andrew Holborn, accessed through ancestry.co.uk

Bracegirdle, Brian (1998) Microscopical Mounts and Mounters, Quekett Microscopcial Club, London, pages 3, 110, 120 and 196, and plates 3H, 3J, 8B and 46P

Bracegirdle, Brian, and James B. McCormick (1993) The Microscopic Photographs of J.B. Dancer, Science Heritage Ltd., Chicago

The Cornhill Magazine (1860) Advertisement from J. Amadio, Vol. 1, advertising section

Dalton, James (1860) The Cleveland Hills, The Magazine of Natural History and Naturalist, Number 1, pages 134-138

Dixon, Edmund Saul (1857) Microscopic preparations, originally appearing in Charles Dickens’ Household Words, vol. 16, reprinted in The Living Age, Vol. 55, pages 346-352

Ecclesiastical Gazette (1859) Advertisement from J. Amadio, Vol. 19, page 95

England birth, marriage, death, census and electoral registers, accessed through ancestry.co.uk

Fourth Report from the Select Committee of Railway Subscription Lists: Together with the Minutes of Evidence and Appendix. South Midland Counties Railway (1837) pages 117-118

Gardeners Chronicle & New Horticulturist (1860) Advertisement from J. Amadio, Vol. 20, pages 63, 183 and 660

The Goldsmiths', Jewellers', Silversmiths', Watchmakers', Opticians', and Cutlers’ Directory (1863) “Barometer and Thermometer Manufacturers .. Amadio F., 5 Birchin-lane, E.C. .. Wholesale” “Manufacturing and Working Opticians .. Amadio, F., 5 Birchin-lane, City; Amadio, JP, 7 Throgmorton-street”, pages 48 and 49

Household Words (1856) Microscopics, Vol. 1, pages 377-381

Illustrated London News (1855) Advertisement from J. Amadio, Sept. 15, page 343; and Nov. 10, page 574

The Lancet (1858) Advertisements from J. Amadio, Vol. 2, Advertiser sections, July 3 through October 16

The Law Times (1859) Advertisement from J. Amadio, Vol. 33, Advertiser section, April 9

The Law Times (1860) Advertisement from J. Amadio, Vol. 34, Advertiser section, March 3

The Living Age (1859) Microscopic photographs, Series 3, Number 57, page 291

London Daily News (1866) Advertisement from J. Amadio, October 6, page 6

London Morning Post (1854) Report of the gas explosion at J. Amadio’s shop, August 31, page 6

London Street Views (accessed June, 2014) Francesco Amadio, Optician, http://londonstreetviews.wordpress.com/2014/06/10/francesco-amadio-optician/

Lynk, Howard (2108) The slides of C.M. Topping - another look, Quekett Journal of Microscopy, Vol. 43, pages 181-193

Marriage record of Francesco (Francis) Amadio and Charlotte Seawards (1798) Parish records of St. Mary Lambeth, accessed through ancestry.co.uk

Marriage record of Charlotte Amadio [the eldest child of Francesco and Charlotte] and Edward Goodall (1822) St. James Clerkenwell, accessed through ancestry.co.uk

Marriage record of Joseph Philip Amadio and Emma Gambling (1850) St. Peter Le Poer, accessed through ancestry.co.uk

The National Magazine 1858) The invisible paragraph, Vol. 3, pages 31-32

Post Office Directory of London (1843) page 68

Post Office Directory of London (1846) page 76

Post Office Directory of London, Commercial and Professional (1851)

Post Office Directory of London, small edition (1846) page 82

Probate record of Francesco Amadio Sr. (1843) accessed through ancestry.co.uk

Probate record of Francesco Amadio (Jr.) (1866) “Probate, 23 April, 1866, effects under £1500 .. The Will of Francisco Amadio formerly of 5 Birchin-lane in the City of London but late of 9 Matson-terrace Kingsland-road in the county of Middlesex Optician deceased who died 4 March 1866 at 9 Matson-terrace aforesaid was proved at the Principal Registry by the oath of Maria Amadio of 11 Church-road Stoke Newington in the County aforesaid Spinster the Sister the surviving Executrix”, accessed through ancestry.co.uk

Probate records of Joseph Philip Amadio (1892 and 1893), accessed through ancestry.co.uk

Probate record of Maria Amadio (1892) “Amadio Maria of 3 Grosvenor Villas Sutton Lane Chiswick Middlesex spinster died 24 January 1892 Administration (Limited) London 13 June to Edward Holroyd Bousfield auctioneer Effects £4471 13s 2d”, accessed through ancestry.co.uk

Proceedings of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society (1859) Minutes of the Ordinary Meeting, March 22, Vol. 1, pages 112-113

Railway Subscription Contracts Deposited in the Private Bill Office of the House of Commons (1837) page iii

Records of Sun Fire Office (accessed May, 2014) MS 11936/475/938045, http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/A2A/records.aspx?cat=074-sun_2-5&cid=-1&Gsm=2012-06-18#-1

Records of Sun Fire Office (accessed May, 2014) MS 11936/500/1028690, http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/A2A/records.aspx?cat=074-sun_2-30&cid=-1&Gsm=2012-06-18#-1

Reports of Committees of the House of Commons on Railway Bills (1836) page 1049

Robson’s London Directory (1842) Robson, London, page 379

The Spectator (1859) Progress of photography, Vol. 32, page 232

The Student and Intellectual Observer of Science, Literature and Art (1869) Last known advertisement from J. Amadio, Vol. 3, March Advertiser