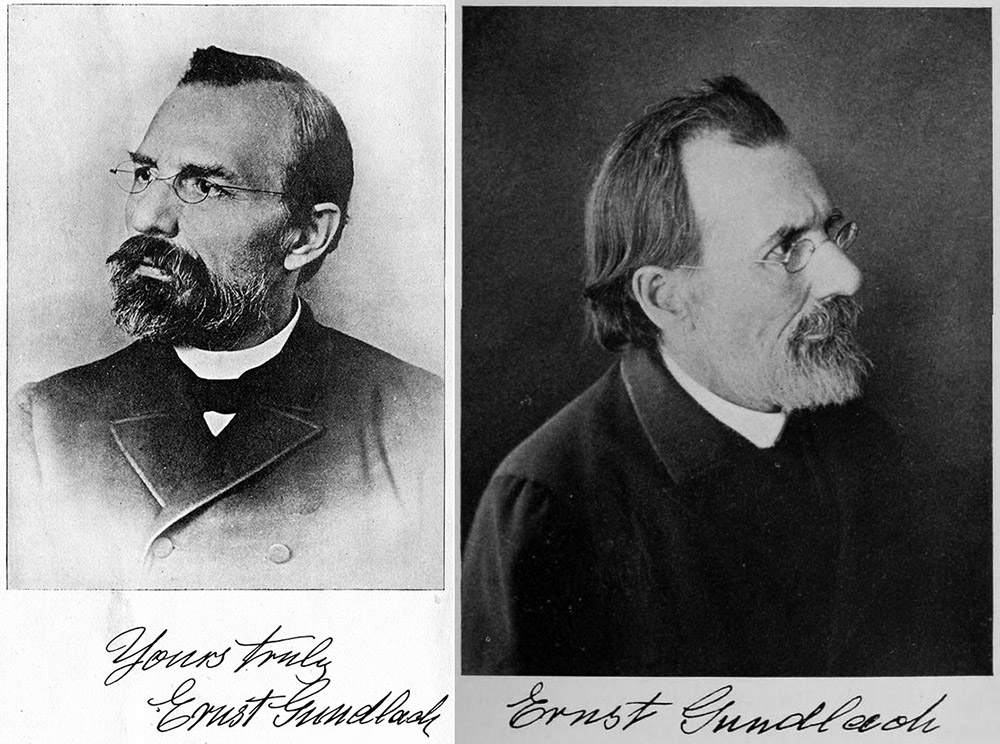

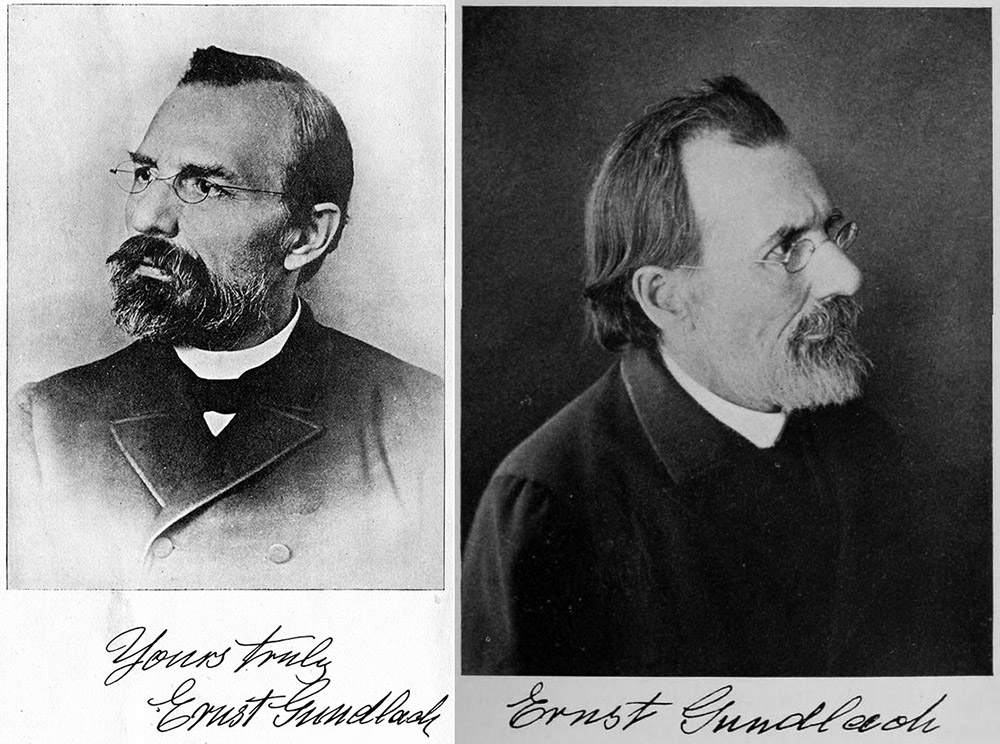

Figure 1. Ernst Gundlach, late in life. Left, from the 1898 photographic lens catalogue of Ernst Gundlach, Son & Company. Right, from “Camera Craft” magazine, 1900.

Ernst Gundlach, 1834 - 1908

by Brian Stevenson

last updated March, 2023

A highly-trained mechanical engineer and a self-taught expert in lens-making, Ernst Gundlach produced numerous innovations in microscopy, photography, and other fields. Throughout his life, he was involved with many different businesses in Europe and North America. Gundlach is best known for his optical companies in Germany and the USA, and for his association with Bausch and Lomb during their earliest days as microscope makers.

Some dates in Ernst Gundlach’s professional life, taken from Gundlach’s writings or from historical records. More extensive details follow Figures 1-19, which display some of the microscopes that are associated with Gundlach’s name:

1849: 15 year-old Ernst Gundlach began his apprenticeship in Berlin with scientific instrument-maker Carl Friedrich Lewert (1807-1889).

1853: After four years of apprenticeship, Gundlach took work with instrument-makers in Vienna, Amsterdam, and Paris. At the latter city, he worked for Oberhaeuser & Hartnack.

1858: Gundlach moved to Wetzlar, Hesse (now Germany) to work for Friedrich Belthle (1829-1869) and Heinrich Rexroth. Belthle & Rexroth were the successors to the optical business of Carl Kellner (1826-1855). The firm was later taken over by Ernst Leitz (1843-1920).

1859: Gundlach formed his own instrument-making business in Wetzlar. He was joined by two other Belthle & Rexroth employees, brothers Wilhelm (1840-1925) and Heinrich (1842-1907) Seibert.

ca. 1860: Gundlach’s Wetzlar business went bankrupt, and he took work in England. The 1861 census of England recorded him as a “machinist” in London. Gundlach later wrote that he also worked in York.

1864: Gundlach moved to Berlin. While working for another business, he began making making his own microscopes during the evenings. After 6 month’s work, Gundlach finished and sold his first Berlin microscope. He was advertising professionally in 1865. At some point, the Seibert brothers joined him.

1872: Gundlach sold his Berlin business to the Seiberts and Wetzlar-based businessman Georg Krafft (the firm of Seibert and Krafft moved to Wetzlar in 1873, and became W. & H. Seibert in 1884). Gundlach and family arrived in New York City on August 22, 1872. He began manufacturing microscope lenses under his own name in Hackensack, New Jersey.

1876: Gundlach moved to Rochester, New York, to head the newly-formed microscope department of Bausch & Lomb (previously called the Vulcanite Optical Instrument Company).

1878: Gundlach left Bausch & Lomb. His former employers retained the patents for Gundlach’s optical inventions. Gundlach remained in Rochester and formed an optical business under his own name.

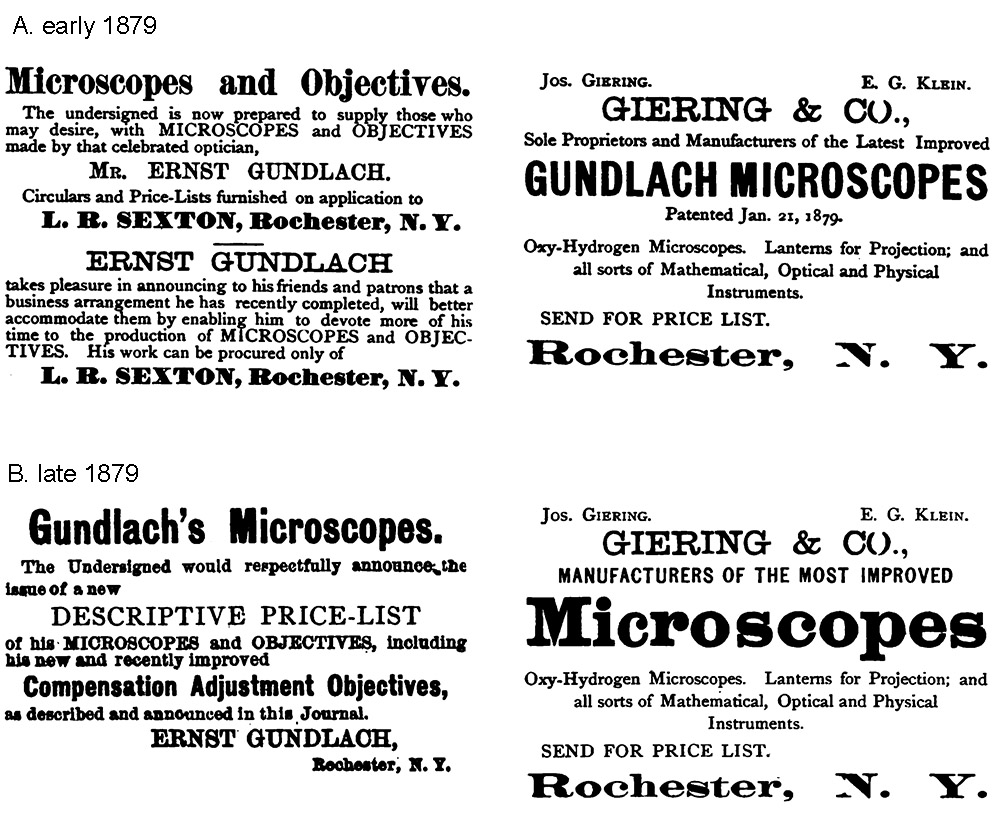

1879: Gundlach established a business relationship with Lewis R. Sexton (1841-1884), with Sexton as distributor of Gundlach’s products. At the same time, Giering & Company, also of Rochester, N.Y., advertised as “sole proprietors and manufacturers of the latest improved Gundlach microscopes”; this may mean that they produced bodies and/or lenses to Gundlach’s orders.

1883: The Gundlach Optical Company was organized in Rochester, consisting of Ernst Gundlach, John Zellweger, Henry H. Turner and John C. Reich.

1884: Sexton resigned from his business relationship with Gundlach, and died shortly afterward. Bausch & Lomb bought Gundlach-produced lenses from Sexton’s estate, then advertised them for re-sale.

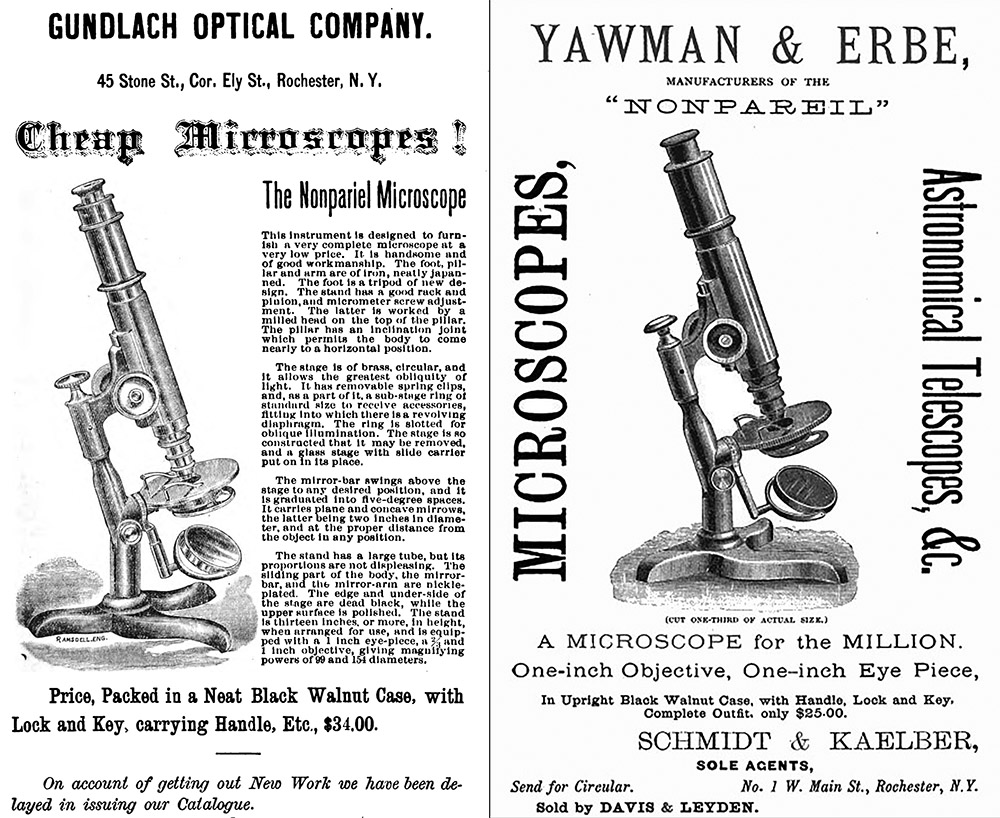

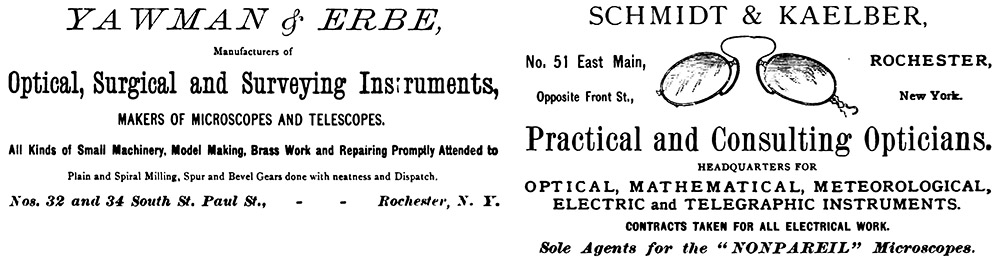

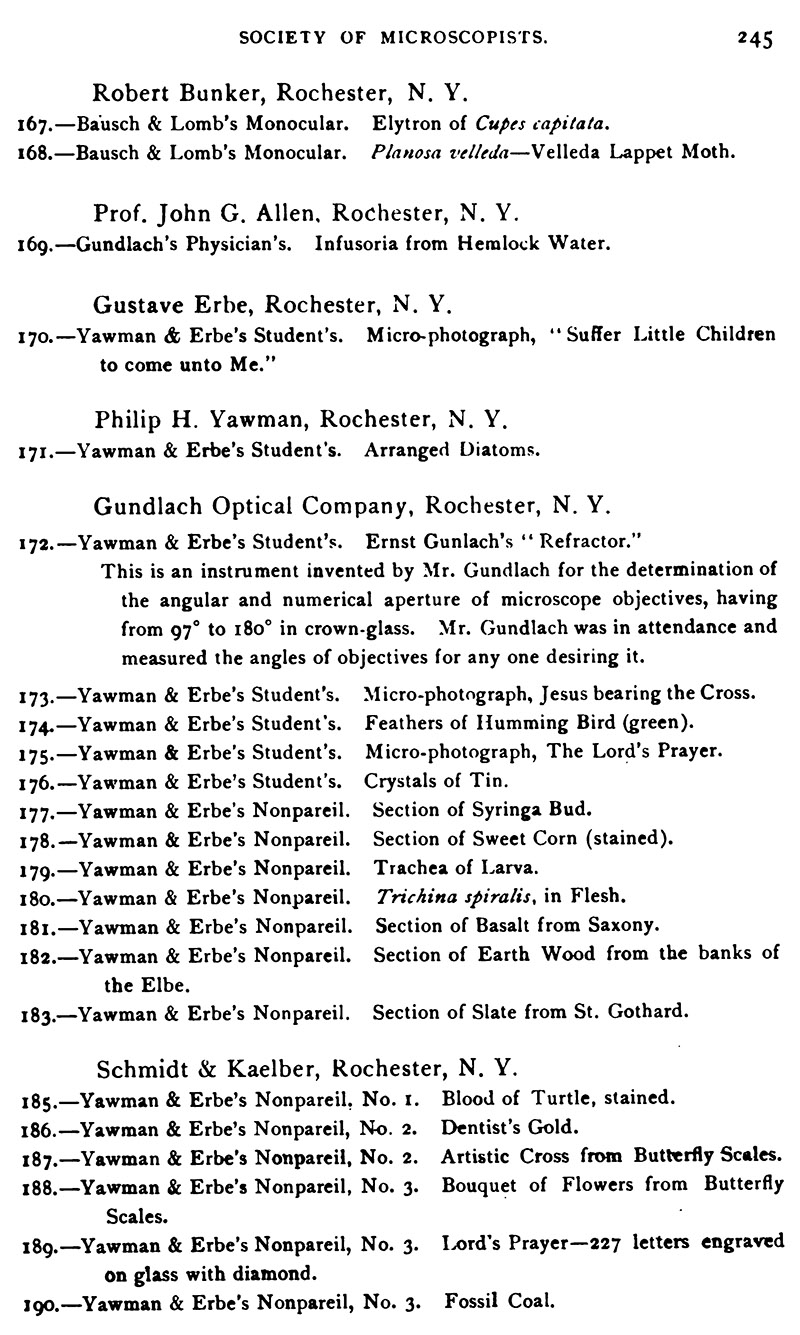

1884: Bodies for Gundlach microscopes were produced by the Yawman & Erbe Manufacturing Company, of Rochester. It was owned by two former employees of Bausch & Lomb, Philip H. Yawman and Gustav Erbe.

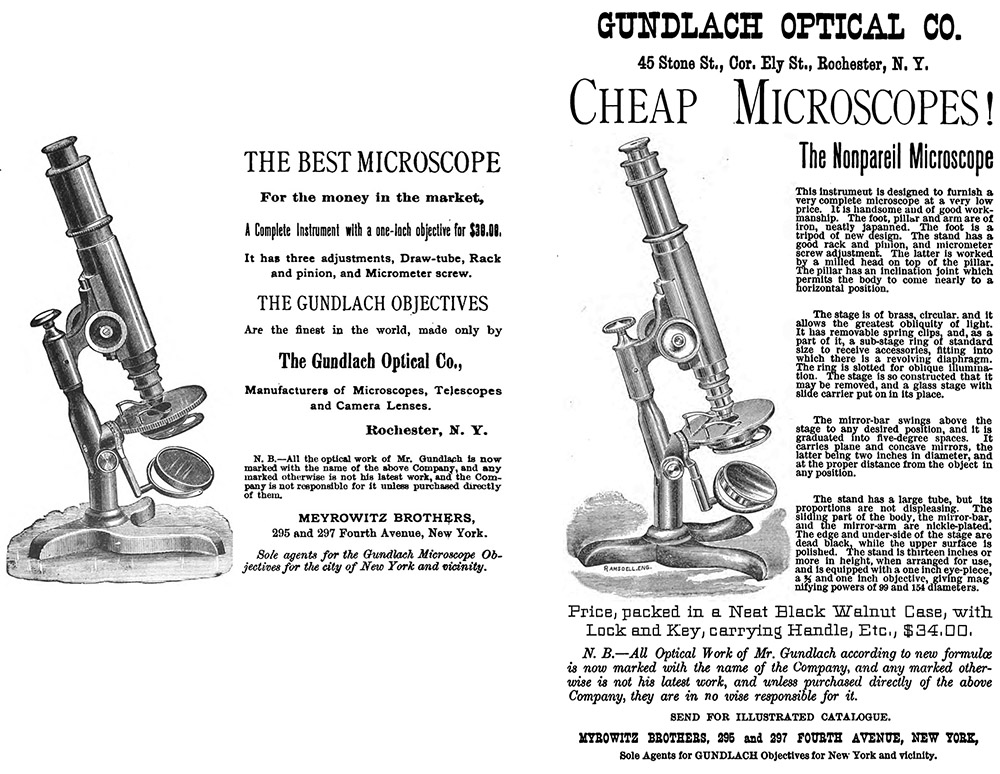

1884: Schmidt & Kaelber, Rochester “opticians and dealers in optical, mathematical and electrical instruments”, became “sole agents for Yawman & Erbe's celebrated stands with the Gundlach Objectives” and distributed those items “all over the United States and Canada”. Other companies later distributed those microscopes and Gundlach’s lenses, such as the Meyrowitz Brothers of New York City.

1895: Gundlach left the Gundlach Optical Company and opened a rival enterprise in the same city, “The Gundlach Photo-Optical Company”. The following year, Gundlach sued his former partners to stop them from using his name (although the terms of Gundlach’s resignation gave the company permission to his name). Gundlach lost the case, and the Gundlach Optical Company remained in business until well into the twentieth century.

ca. 1898: The Gundlach Photo-Optical Company changed its name to “Ernst Gundlach, Son & Company”. The company’s assets were seized in October, 1898.

1899: Ernst Gundlach moved to Chicago to head the lens-making department of the Vive Camera Company.

ca. 1905: Gundlach and family moved back to Berlin. The November 5, 1905, issue of Der Mechaniker listed “Ernst Gundlach & Sohn, Elektrotechniker” under newly-formed businesses.

1908: Ernst Gundlach died.

Figure 1.

Ernst Gundlach, late in life. Left, from the 1898 photographic lens catalogue of Ernst Gundlach, Son & Company. Right, from “Camera Craft” magazine, 1900.

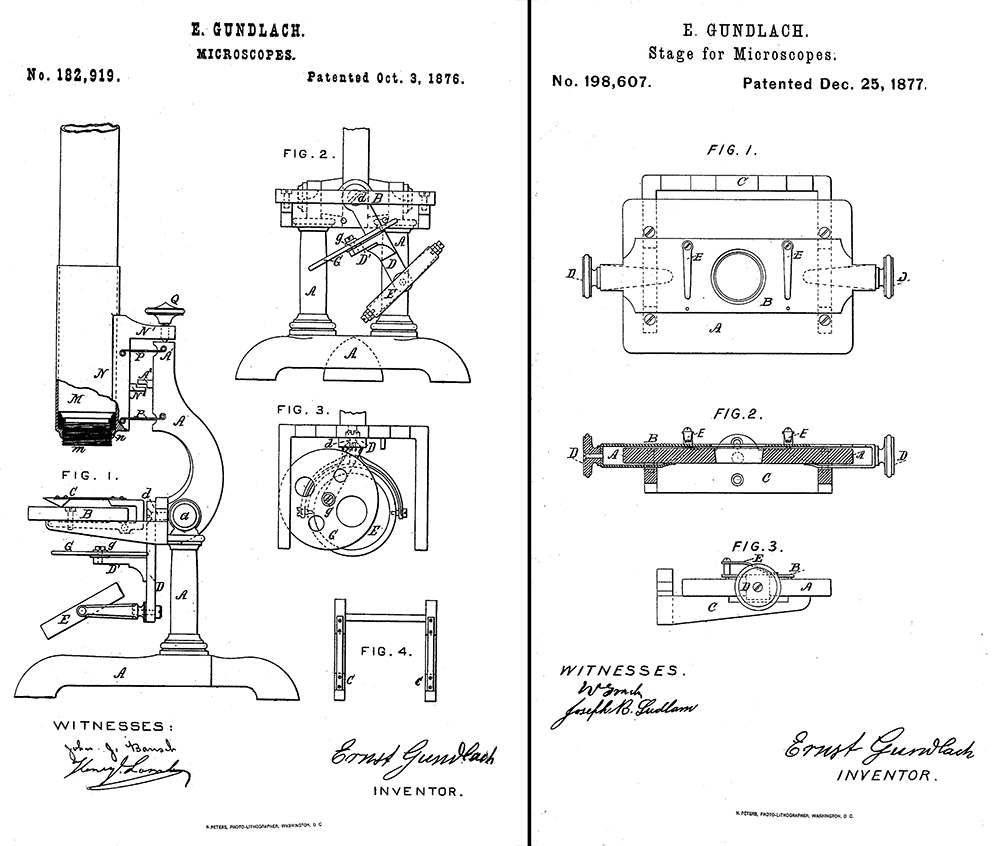

Figure 2.

Gundlach “Stand 7” microscope, serial number 120, circa 1867. Adapted with permission from https://www.musoptin.com/item/kleines-mikroskop-e-gundlach-in-berlin-120-1867.

Figure 3.

Gundlach “Stand 5” microscope, serial number 239, circa 1868. Adapted with permission from https://www.musoptin.com/item/mittleres-mikroskop-ernst-gundlach-239-um-1868.

Figure 4.

Gundlach “Stand 2” microscope, serial number 385, circa 1869. Adapted with permission from https://www.musoptin.com/item/grosses-mikroskop-ernst-gundlach-385-um-1869.

Figure 5A.

Gundlach “Stand 5”, serial number 686, circa 1870. Another microscope, with serial number 948, was made near the end of his time in Berlin, and is essentially identical to number 686. Adapted with permission from a private collection.

Figure 5B.

Circa 1874 microscope by Seibert and Krafft, which is essentially identical to the Gundlach “Stand 5” that is shown in Figure 5A. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Figure 6.

Charles Baker became the English agent for Gundlach’s lenses in 1871. That arrangement ended during the next year, when Gundlach left Germany for the USA. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Figure 7.

Illustrations of two Ernst Gundlach patents that were awarded when he worked for Bausch & Lomb: “Improvement in Microscopes”, 1876, consisting of new fine-focusing mechanisms and substage/mirror design, and “Stage for Microscopes”, 1877, a thick glass stage with sliding brass slide-holder. His employers retained rights to the patents after Gundlach left in 1878.

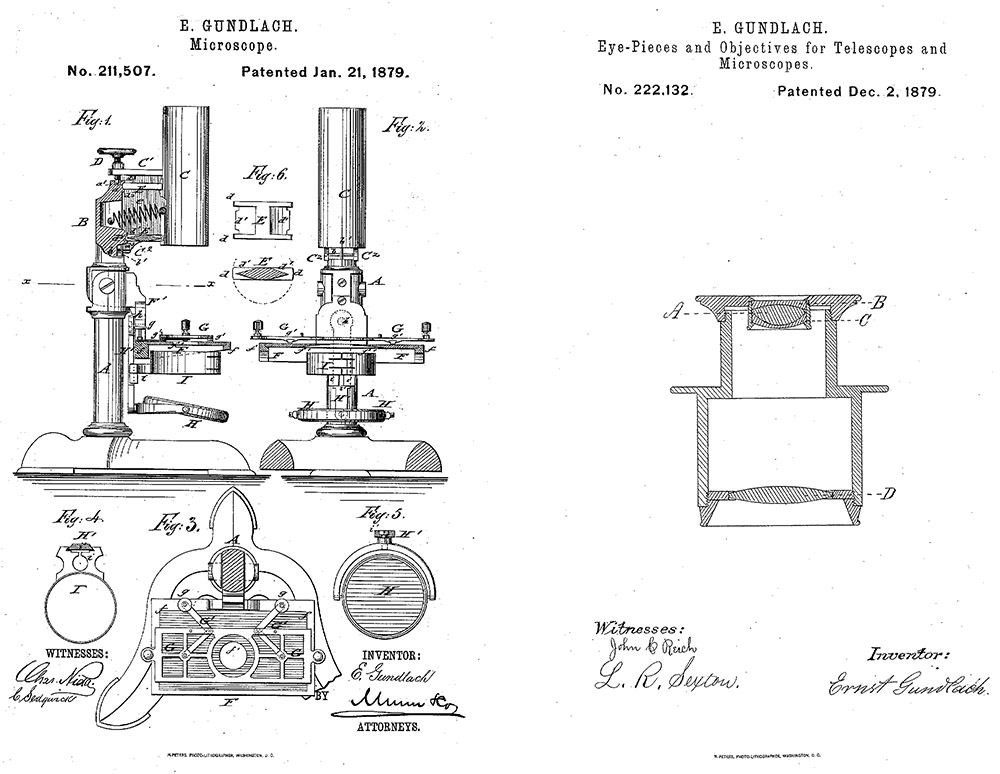

Figure 8.

A ca. 1876 Bausch & Lomb “Professional”, serial number 76, designed under Ernst Gundlach’s supervision and incorporating features patented by him in 1876 and 1877 (Figure 7). The objective lens-holders and several other components were made of vulcanized rubber, an adaptation by Bausch and Lomb of the vulcanite they used for eyeglass frames (until just before Gundlach joined the firm, in 1876, it was known as the Vulcanite Optical Instrument Company). Images adapted by permission from http://www.antique-microscopes.com/photos/B_L_Professional_microscope_76.htm.

Figure 9.

A ca. 1877 Bausch & Lomb “Laboratory” microscope, serial number 279, designed under Gundlach’s supervision and incorporating features patented by him in 1876 (Figure 7). Not the extensive use of vulcanized rubber for the stage and lens mounts. Images adapted by permission from http://www.antique-microscopes.com/photos/B&L_Laboratory_microscope.htm.

Figure 10.

Bausch & Lomb “Student” microscope, designed under supervision of Gundlach and including features patented by Gundlach in 1876 and 1877. Serial number 559, manufactured ca. 1878. Adapted by permission from http://www.antique-microscopes.com/photos/Bausch_Lomb_student_microscope_1878.htm.

Figure 11.

ca. 1878 “Research” microscope, serial number 643, designed under Gundlach and using his 1876 patent. Adapted by permission from http://www.antique-microscopes.com/photos/Bausch_Lomb_Research_model_microscope_643.htm.

Figure 12.

Bausch & Lomb “Physician’s” microscope, also designed when Ernst Gundlach managed the microscope division of Bausch & Lomb, and which includes features patented by Gundlach in 1876 and 1877. Serial number 1078, manufactured ca. 1879. Adapted by permission from http://www.antique-microscopes.com/photos/B_L_physicians_microscope_1078.htm.

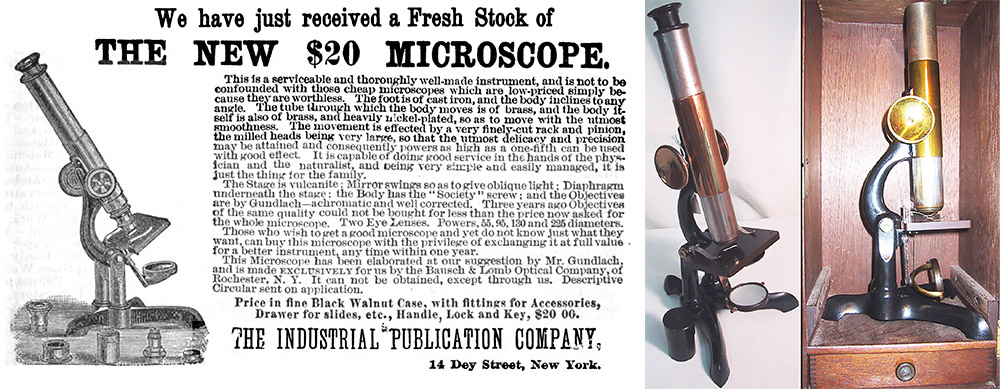

Figure 13.

1879 patents by Ernst Gundlach, filed shortly after leaving Bausch & Lomb. An example of the model shown in the left illustration has yet to be identified.

Figure 14.

A September, 1879 advertisement for a Bausch & Lomb “Family” model microscope outfitted with Ernst Gundlach lenses. The advertisement notes that this microscope model was designed under Gundlach’s supervision while he was with Bausch & Lomb. The center and right images are photographs of an extant “Family” microscope, adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet sale site. Note the vulcanized rubber mount of the ocular lens.

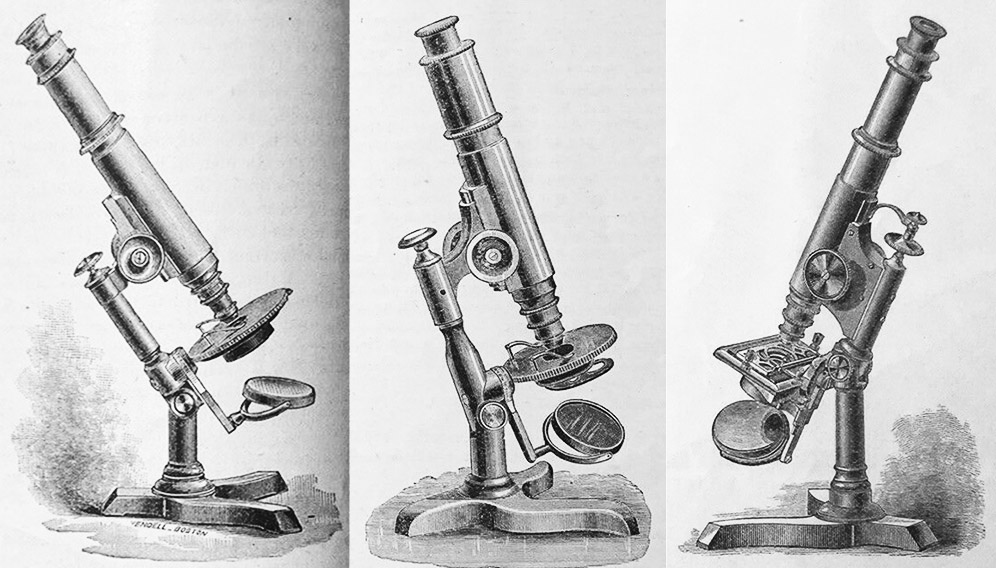

Figure 15.

Ernst Gundlach left Bausch and Lomb in May, 1878, then began producing and selling microscopes under his own name. This is his "Student’s Microscope Number 1", as illustrated in the 1882 catalogue of Gundlach microscopes that was published by L.R. Sexton (see Figure 15B). Adapted by permission from http://www.antique-microscopes.com/photos/Ernst_Gundlach_microscope.htm.

Figure 15B.

Illustrations from L.R. Sexton’s 1882 catalogue of Gundlach microscopes. Left to right, they are "Student’s Number 1", "Nonpariel", and "College" models. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Figure 16.

Circa 1881 microscope with a Gundlach objective lens. An identical microscope is known whose case is stamped “L. R. Sexton, Gundlach Microscopes & Objectives, No. 21 Stone St., Rochester, NY.” From 1879 until Sexton’s death in 1884, Gundlach sold his microscope lenses through Sexton. It is not evident who manufactured this microscope body.

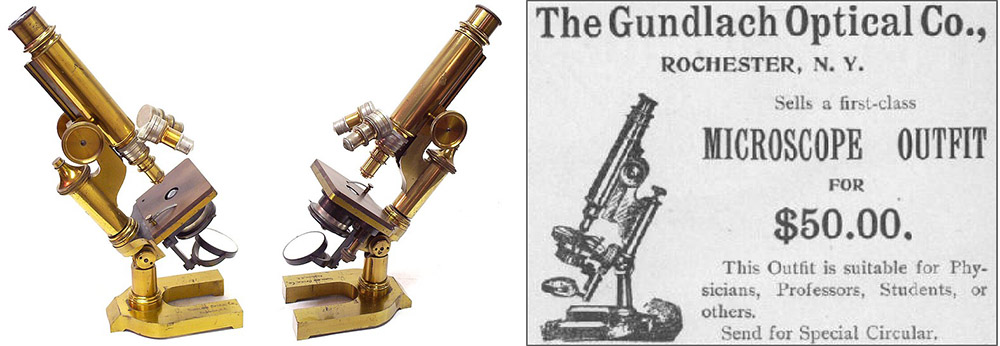

Figure 17.

ca. 1884 “Nonpareil” microscope. The optics were made by Ernst Gundlach and the body by Yawman & Erbe, each of which is signed by their maker. Other combinations of the names are known to exist - see http://www.antique-microscopes.com/photos/nonpareil.htm. The accompanying objective lenses and their canisters are all signed “Gundlach Optical Company”, which was formed in 1883. Adapted with permission from a private collection.

Figure 18.

ca. 1895 microscope from the Gundlach Optical Company. Ernst Gundlach left that firm in 1895. Images adapted with permission from http://www.antique-microscopes.com/photos/Gundlach_optical_microscope.html.

Figure 19A.

ca. 1905 “Simplex” microscope by the Gundlach Manhattan Optical Company (formed in 1902 by the acquisition of Manhattan Optical by the Gundlach Optical Company). Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Figure 19B.

ca. 1905 case-mounted version of the Gundlach Manhattan “Simplex” microscope. Adapted with permission from a private collection.

Some details of Ernst Gundlach’s early life were published in his 1898 Photographic Lenses catalogue (as Ernst Gundlach, Son, & Co.), and in an 1882 biography that appeared in The Proceedings of the American Society of Microscopists.

Ernst Gundlach was born during 1834 in Pyritz, Pomerania (then part of Prussia, now in Poland). In 1849, when 15 years old, he apprenticed in Berlin with scientific instrument-maker Carl Friedrich Lewert. He left Lewert after “four years” (i.e. 1853).

Gundlach’s 1898 autobiography condensed the next 11 years into a single paragraph: “he began to extend his mechanical studies and skill by working successively in the most distinguished work shops in Europe, at Vienna, Paris, London, York, etc., by always executing only the best work in scientific instruments”.

That time evidently included work with Oberhaeuser & Hartnack in Paris, then with Belthle & Rexroth in Wetzlar, circa 1858.

Gundlach later wrote, “Most of these work shops were such where optical lenses were also ground, and in chosing these optical shops, Mr. Gundlach was seeking to find a chance to learn or find out the mode how optical lenses were made. But in this attempt he always failed, since the European opticians carefully keep their lense grinding department separated from the others, and do not allow anybody to enter who does not belong to the department”. This indicates that Gundlach’s formal training dealt with the mechanical aspects of scientific instruments, i.e. “the brass”, and that he taught himself “the glass”.

After working with Belthle & Rexroth for a while, Gundlach began his own scientific instrument business. He lured Wilhelm and Heinrich Seibert away from Belthle & Rexroth. This business did not survive for long, and Gundlach left for England (noted in his autobiography, above).

The 1861 national census of England listed Gundlach as a “machinist” in St. Giles, Middlesex. With him were his wife, Emilie, and a one year-old daughter, Emilia. London then had numerous scientific and optical factories. During his English sojourn, Gundlach also worked for some time in Yorkshire.

Gundlach returned to Germany circa 1864, settling in Berlin. His autobiography states that Gundlach worked for an employer for some time: “day-time had to be devoted to earning his bread and butter”. In the evenings, he taught himself how to grind lenses. From his 1898 autobiography, “In 1864 he commenced practical optics, or rather tried to do so. He built a little machine for grinding lenses, after his own ideas, not knowing anything about other machines or how they were constructed, and … he worked evenings with this crude machine, trying to produce a little lens out of a piece of window glass. This was a hard task, for he did not then know anything about lens grinding, excepting that emery was used for grinding and rouge for polishing. However, before six months had passed, he had his first microscope completed, three objectives, two eye pieces and the stand, all complete”. The 1882 biography tells the same tale, but set it two years later, “in 1866, he started optical work for himself, knowing nothing of the methods of others, except that emery is used for grinding, and rouge for polishing lenses. Technical difficulties soon presented themselves, only to be overcome by the enthusiasm of the young optician, and in about six months he had completed his first microscope, with three objectives and two eye-pieces”. Gundlach advertised microscopes for sale in 1865 (Figure 20), implying that the 1864 date is likely to be correct.

The Siebert brothers again worked for Gundlach, supplying him with mechanical parts and optics.

Gundlach exhibited “microscopes et loupes” at the 1867 Paris International Exposition, and was awarded a medal (Figure 21). His display included glycerin-immersion objective lenses. Viewers were very impressed with the quality and low prices of Gundlach’s instruments, publishing comments such as “M. Gundlach, en Prusse, et M. Mirand, en France, ont exposé des instruments supérieurs aux précédents par leur construction, et qui peuvent servir à des études sérieuses, malgré la modicité de leur prix” (“Mr. Gundlach, of Prussia, and Mr. Mirand, of France, exhibited instruments that were superior to previous constructions, which can be used for serious studies despite the modest price”), and “Nous citons encore les microscopes de Gundlach de Berlin à cause de leur bon marché” (“We again cite the microscopes of Gundlach from Berlin because of their low price”).

Gundlach’s autobiography records that “in 1869 he was prostrated by a severe attack of typhoid fever, which disabled him entirely for a period of over six months”.

Also in 1869, a report to the Royal Microscopical Society stated, “a young optician named Gundlach, of Berlin, has succeeded in making object-glasses, which are cheaper and more powerful than those of Hartnack and other opticians. His No. 7 is better than Hartnack's No. 9 or No. 10, at less than half the price of the No. 9. It has higher magnifying power, more light, and greater focal distance. … Gundlach's No. 8 is better than Hartnack's No. 14, and is only a third of the price”.

In 1870, Gundlach made arrangements for John Winspear of Hull, Yorkshire, to be sole distributor of his lenses in England (Figure 22). An article in the May, 1870 issue of The Monthly Microscopical Journal wrote, “Mr. Slack called the attention of the meeting to a series of microscopic objectives made by Herr Gundlach, of Berlin, whose agent in England was Mr. Winspear, of Hull. The Gundlach objectives were remarkable for combining a very considerable amount of merit with unusually low price. The lower powers, 2-inch, 1-inch, 1 1/2-inch, were sold by Mr. Winspear at 17s., and 1/12th and 1/16th immersion lenses at 3£ 12s. 6d, including the Society's standard screw and brass boxes”.

Winspear seems an odd choice for an English distributor, as Hull was far from London and other centers of scientific studies. Noting that Gundlach wrote of having worked in “York” during the early 1860s, it is possible that he had worked alongside Winspear, and was thus known and trusted. Nonetheless, Gundlach quickly found a more appropriate distributor in Charles Baker, of London. Baker became sole distributor by the beginning of 1871 (Figure 23).

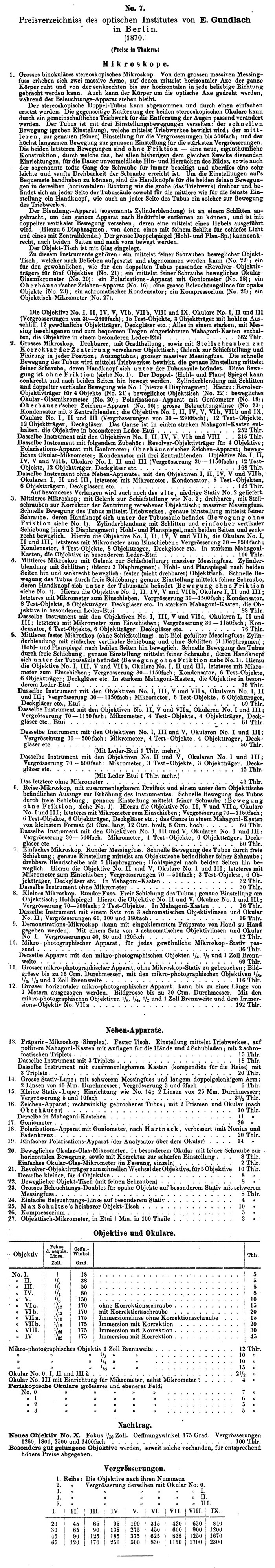

An 1870 Gundlach catalogue, reproduced in Heinrich Frey’s 1871 Das Mikroskop und die Mikroskopische Technik listed a large binocular stereoscopic microscope, one large and three medium monocular microscopes, and other, simpler instruments (Figure 24).

In mid-1872, Gundlach sold his optical business to Wilhelm and Heinrich Seibert. A Wetzlar-based industrialist, Georg Krafft, helped finance the Seibert’s acquisition. The new partnership of Seibert and Krafft moved to Wetzlar in 1873, then became W. & H. Seibert in 1884.

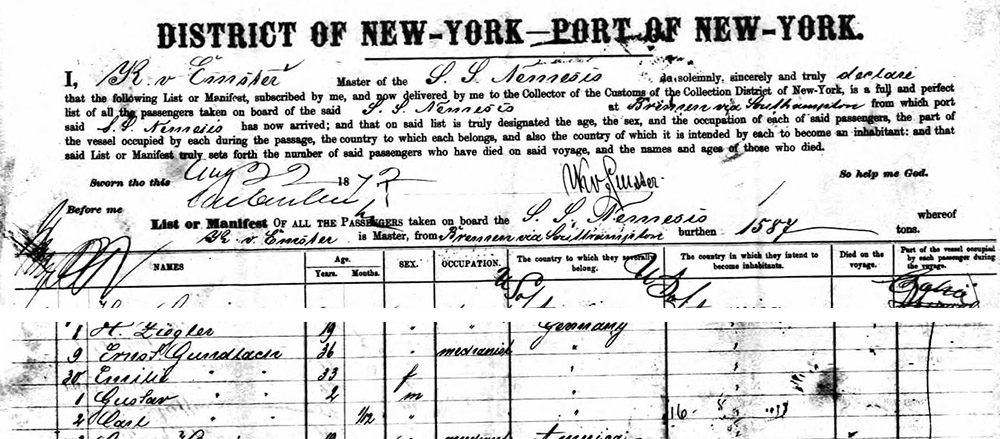

The Gundlach family arrived in New York City on August 22, 1872 (Figure 25). In addition to Ernst and his wife, Emilie, were sons Gustav (age 4) and Carl (age 6 months). Notably absent was daughter Emilia, who was recorded in the 1861 English census, and who would have been about 12 years old. Presumably, she had died. Noting the span of time between Emilia’s and Gustav’s births, and Ernst’s debilitating attack of typhoid fever in 1869, it is possible that other Gundlach children had passed away.

The Gundlachs settled in Hackensack, New Jersey, and Ernst began producing microscope lenses and other items. The January, 1873 issue of The Lens reported, “We are glad to be able to note … the removal of Mr. Gundlach from Berlin to the United States. He has established himself at Hackensack, N.J., where he will devote himself to the production of first-class objectives only. His scale of prices will be found to be very low. In our next number we shall publish a paper by Prof. F. Ardissonne, of Milan, communicated to the Nuevo Giornale Botanico Italiano, giving the relative resolving power upon well known test-objects of various objectives of the best continental makers, including Mr. Gundlach, from which it appears that Mr. G's objectives did him high honor. One of them, a sixteenth, equivalent to his No. VII (European nomenclature), now belongs to Mr. H.H. Babcock, of Chicago, who mentions it to us in terms of unqualified praise”.

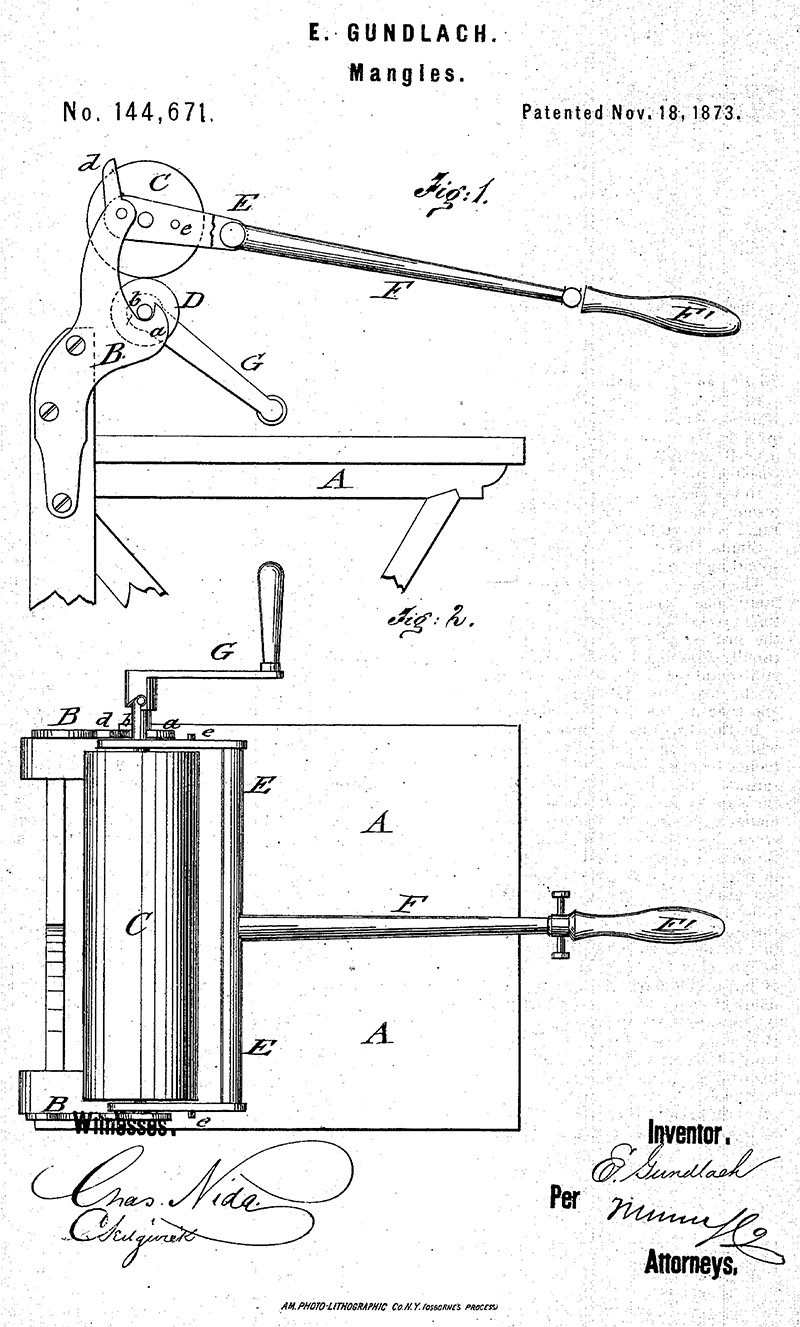

In addition, Gundlach sought other sources of income. In November, 1873, he patented a new form of mangle for extraction of water from laundry (Figure 26).

Until Gundlach joined them in 1876, the business of John Jacob Bausch (1830-1926) and Henry Lomb (1828-1908) had been called the Vulcanite Optical Instrument Company, which drew attention to their use of hardened rubber for eyeglass frames. Gundlach was hired to expand the company’s repertoire to include microscopes. The firm then became Bausch & Lomb. For the first several years of production, Bausch & Lomb extensively used vulcanite rubber in their microscopes, for items such as stages and lens mounts (see Figures 8-10). After a while, it became obvious that rubber was not solid enough to hold microscope lenses firmly in position, and the company switched to the industry standards of brass and steel.

Gundlach was with Bausch and Lomb in time for the US Centennial International Exposition of May-November, 1876. Their exhibited microscopes included designs that Gundlach patented in August, 1876. The Royal Microscopical Society’s Monthly Microscopical Journal wrote “Bausch and Lomb, of Rochester, who have lately added to the province of the Vulcanite Optical Instrument Company, of that city, a microscopical department, under charge of E. Gundlach, formerly of Germany and late of Hackensack, N.J., exhibit a large series of entirely new designs. These are all of excellent workmanship, though of low or medium grade as to size, complexity, and cost. By simplifying the designs, introducing vulcanite into the mountings where it can be done to advantage, and introducing the business principle of attempting to create a large demand by production at a very low cost, the experiment of offering good instruments at a very low rate is being tried on a scale and with facilities unprecedented in this country. The special peculiarities of these stands, aside from the vulcanite mountings, are the hinging of the sub-stage bar at the level of the object, contesting in this respect the priority with Zentmayer’s new stand‘; a new object carrier, which with some improvements may be convenient; a new fine adjustment, by means of a screw acting on the body, which is supported at the end of two parallel horizontal springs, which allow a peculiarly smooth motion practically incapable of deterioration from wear or any other probable cause; and a coarse adjustment, consisting of a slide at the upper part of its course, and, below, a rapid screw which prevents pushing the body suddenly through the slide, and, without interfering with a prompt adjustment of low powers by sliding, gives a delicate adjustment for higher powers by screwing. This method is evidently a modification of Wale’s oblique slot”.

Gundlach left Bausch & Lomb in March, 1878. Gundlach did not provide details of this parting-of-ways in his autobiography. With the caveat that John Jacob Bausch may have harbored bad feelings for his former employee, Bausch wrote of Gundlach, “he was a peculiar man and I was obliged to handle him carefully … The man never knew the value of money and had no experience whatever in conducting a business. In this way it came about that we lost much money. … After he had been with us a year and half the first outbreak occurred. I cannot say what the reason was but it was a trifle, and for several successive days he did not come to work. … Six months later Mr. Gundlach stayed away again, writing a letter in which he stated that he did not wish to return. He remained at home in idleness and whenever he needed money he sent for it”.

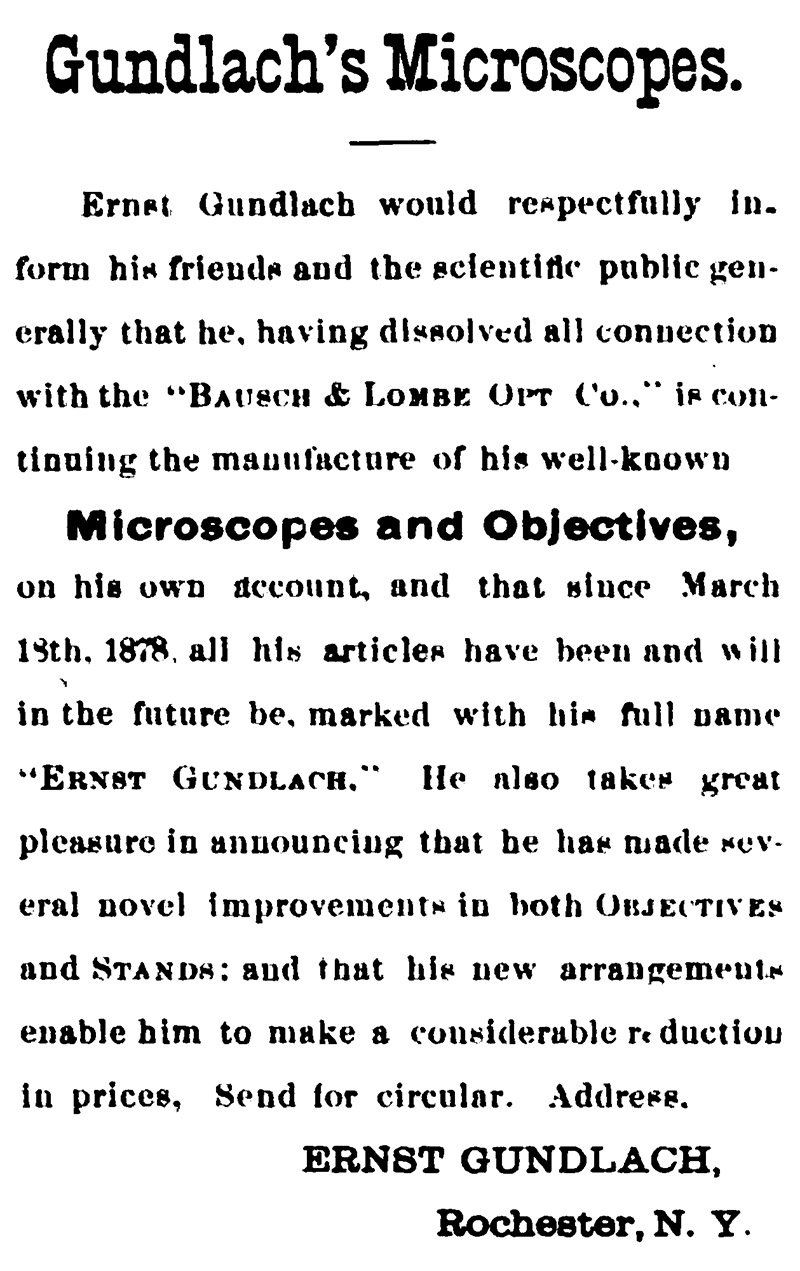

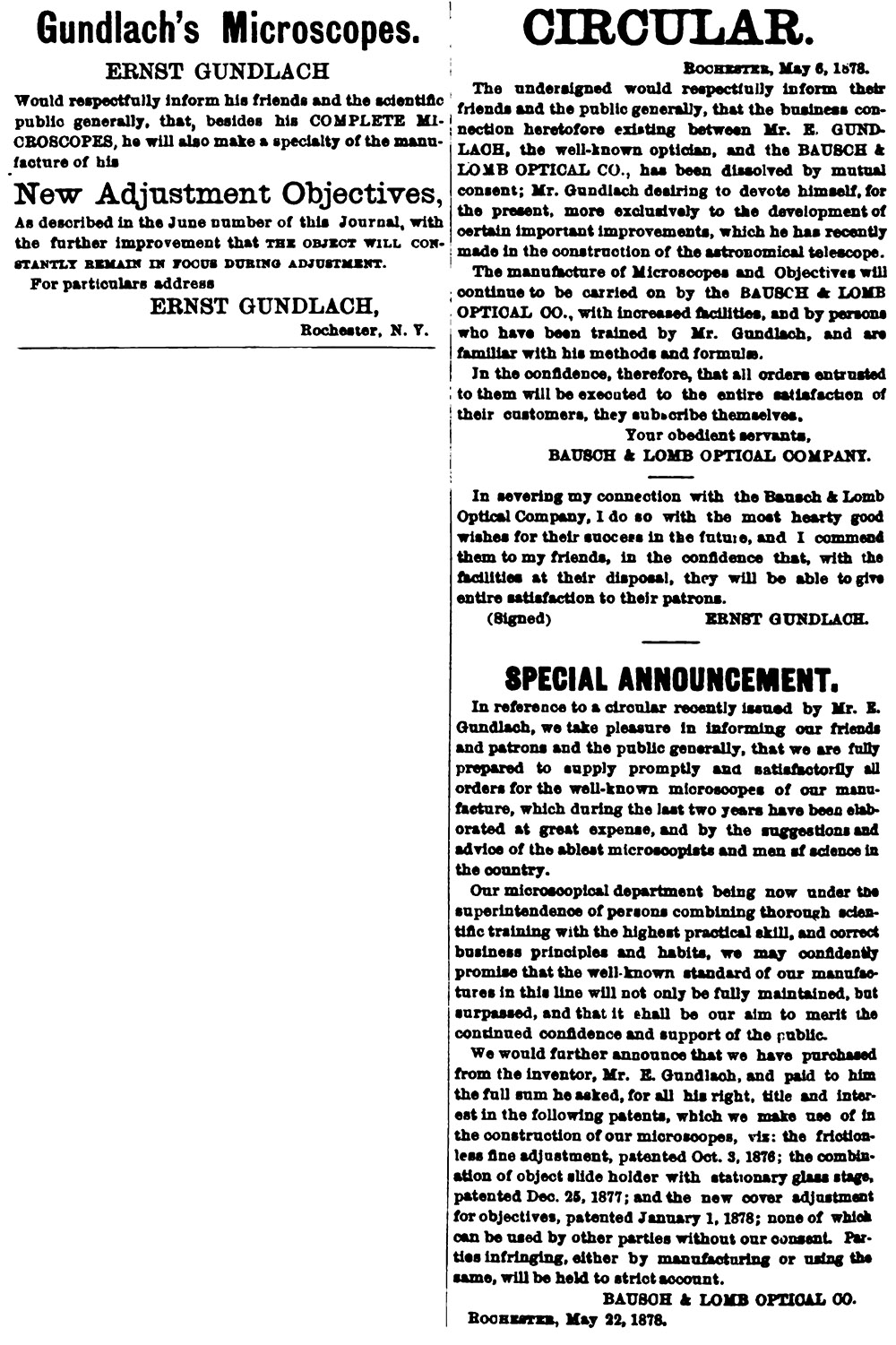

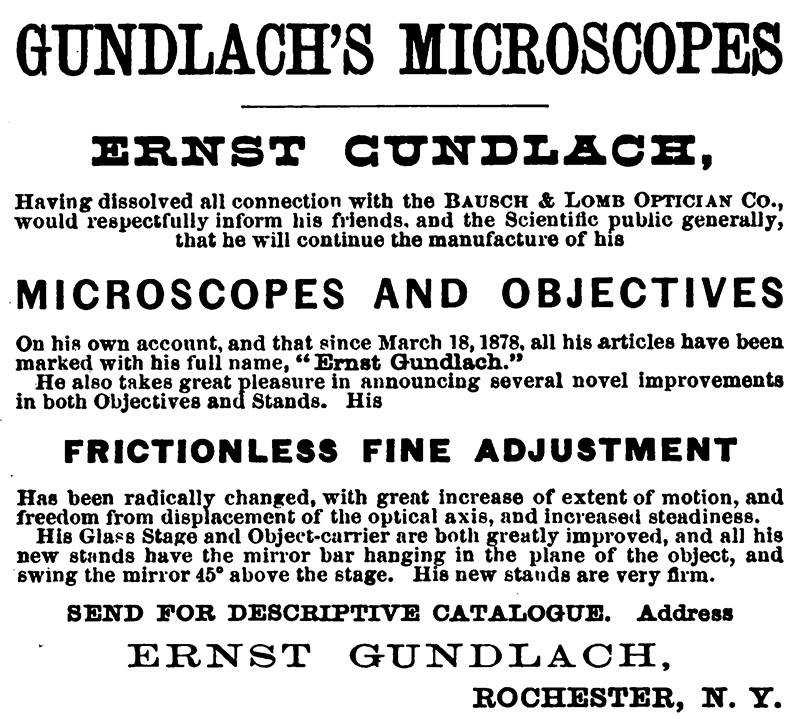

Gundlach published advertisements declaring that, as of March 18, 1878, he had left Bausch & Lomb and formed his own company to manufacture “Microscopes and Objectives” (Figures 27-29).

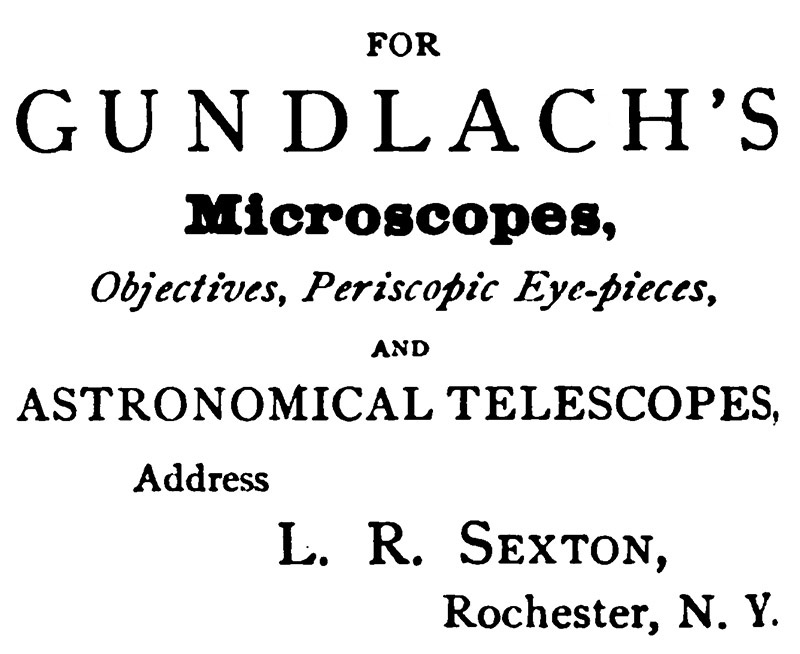

By 1879, Gundlach had evolved a new business scheme: he would produce microscope lenses, while Lewis R. Sexton managed their distribution (Figures 30-31). As discussed below, Sexton evidently purchased Gundlach’s lenses, then re-sold them. Complete microscopes were apparently included in the arrangement, probably made to Gundlach’s designs (Figures 15-16).

Production of those microscope bodies was outsourced to some extent - in early 1879, Giering & Co. of Rochester, advertised that they were “manufacturers of the latest improved Gundlach microscopes” (Figure 31A). Also in 1879, Gundlach filed a patent for “improvement in microscopes” (Figure 13). Giering’s 1879 advertisement stated that the microscopes that they manufactured for Gundlach incorporated this patent (Figure 31A). Curiously, by the end of 1879, Giering & Co. no longer mentioned Gundlach in their advertising, while another ad on the same page stated that “Gundlach’s Microscopes” were to obtained directly from him (Figure 31B). Presumably, Gundlach broke with Giering and either hired machinists in-house or found another external source for microscope components.

The December, 1879 issue of The American Naturalist reported on the Gundlach-Sexton business, and on Gundlach’s latest developments, “Ernst Gundlach - This well-known optician announces another business change, by which he will devote his time exclusively to manufacturing, and L.R. Sexton, of Rochester N. Y., will attend exclusively to the department of business correspondence, selling goods, etc. He claims to have recently made great improvements in objectives and oculars, and to have invented an entirely new form of binocular arrangement, description of which is not yet published. He announces five styles or classes of objectives, as follows: Class A, triplets, consisting of a crown glass lens cemented between two flint glasses of different kinds, mounted in the back part of a tube, which has a diaphragm in front to cut off stray light; these triplets ranging from a 4 inch of 8 degrees to 1 1/2 inch of 18 degrees. Class B, dialytic objectives, consisting of two separated achromatic combinations, arranged with special reference to flatness of field. These are of two grades; the first composed of two doublets, and ranging from a 4 inch of 10 degrees to a 1/2 inch of 40 degrees; and the second composed of two triplets, and ranging from a 2 inch of 24 degrees, requiring a microscope body with internal screw one inch wide, to a 1/2 inch of 36 degrees; these triplets can be separated, giving half of the same powers. Class C, aplanatic objectives, three system lenses, the front being a triplet, having large flat field, and chemical and visual foci nearly together, specially suited for photography, and ranging from a 1 inch of 26 degrees to a 1/4 inch of 80 degrees. Class D, resolving objectives, three systems, and either dry, or glycerine immersion ; the former varying from a 1/2 inch of 100 degrees, requiring an internal screw of one inch to a 1/8 inch of 130 degrees, and the latter from a 1/4 inch of 115 degrees water angle, to a 1-16 inch of 120 degrees water angle. Class E, cedar oil immersions, four systems, with long working focus and high resolving qualities, varying from a 1/4 inch of 140 degrees water angle, requiring an internal screw of 1 inch, to a 1-25 inch of 150 degrees water angle. Mr. Gundlach introduced at the meeting of the Rochester Microscopical Society, on the 13th of October, last, a ‘globe lens’, consisting of a hollow sphere of flint glass, made in halves, and containing a solid sphere of Crown glass of certain proportionate density. A corrected lens is thus obtained, having long working focus in addition to the well-known advantages of the Coddington form. As yet they have only been made as pocket magnifiers”.

Sexton took the business to heart. In 1880, he published A Descriptive Catalogue of Gundlach’s Microscopes and Objectives, and Other Optical Instruments. He made himself well-known at gatherings of potential customers, such as the 1880 meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, where it was reported, “Mr. L.R. Sexton, of Rochester, N.Y., was another of the new faces we met with at the Detroit meeting. He represented the manufactory of Mr. E. Gundlach, of Rochester, N.Y., and had a large assortment of stands, eye-pieces, objectives, etc., of Mr. Gundlach's make”, and “Mr. Gundlach was well represented by Mr. L.R. Sexton, who exhibited several very neat and efficient stands, and some very excellent objectives. Among the improvements presented by Mr. Gundlach, is new diaphragm, which can be brought close up to the slide, or removed from it at pleasure. The diaphragm plate is a section of a hollow sphere. This form has been used before for the purpose of enabling the plate to be brought near the slides, but Mr. Gundlach has mounted it in an improved manner, which adds greatly to its efficiency and convenience. To the excellence of Mr. Gundlach’s objectives, very strong testimony will be found in our correspondence as published in this issue”.

Gundlach introduced a new mode of fine adjustment in 1881. Sexton displayed examples at that year’s meeting of the American Microscopical Society, “Mr. L.R. Sexton, of Rochester, exhibited, as agent for Mr. Ernst Gundlach, one of the new stands with a very ingenious fine adjustment, consisting of a Hunterian or double screw. The outer, or ordinary screw, having sixty threads to the inch, has, in the ordinary form, a pin inserted in the lower end, to prevent all lateral motion. In the new form this is replaced by a smaller screw, having seventy-two threads to the inch, and extending clear through the outer screw, and resting on a double-pointed pin. When, now, the inner screw turns with the outer, as it generally will through friction, we have the ordinary screw adjustment. But when, by clamping the inner screw at its upper end, it is prevented from turning, the outer screw turns upon it and the lever on which the pin rests is moved only by the difference in the thread of the two screws, which in this case would be 1-360 of an inch; thus giving, for high powers, a delicacy of focusing far in advance of anything before attained, yet still allowing the use of the ordinary fine adjustment for moderate powers”.

By 1882, Gundlach had become renowned as a significant contributor to the development of microscopes in the USA. The 1882 Proceedings of the American Society of Microscopists included a detailed biography of Gundlach’s life and works.

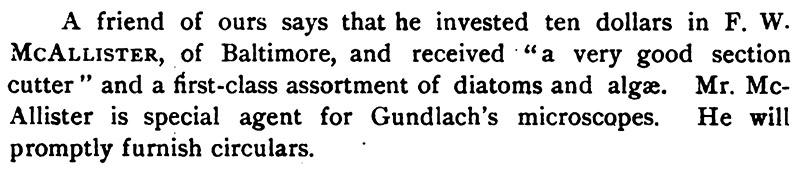

Although Sexton supposedly had a monopoly on selling Gundlach’s microscope lenses, that evidently did not extend to Gundlach’s microscope bodies. An October, 1883 note in The Microscope stated that F.W. McAllister of Baltimore was “special agent for Gundlach’s microscopes” (Figure 32).

During the summer of 1884, Sexton sold off his inventory of Gundlach lenses, then died on August 28, 1884. He was only 43 years old. This was reported in The Microscopical Bulletin, “Following closely the announcement of retirement from business of L.R. Sexton, comes the news of his death, which occurred at Canandaigua, New York, about three days after the night of the Rochester soiree. Mr. Sexton was principal of a large school in Rochester. As agent for Gundlach's optical work he was well known to our readers. He had been in very poor health for several years, and we regret exceedingly to hear of the death of one with whom we have had pleasant business and personal relations”.

Ironically, it was Bausch & Lomb who purchased Sexton’s entire stock of Gundlach lenses (Figure 34). Thus, Gundlach’s former employers sold his lenses for several years during the mid-1980s, long after he had left the firm (Figure 35).

In 1883, Gundlach formed The Gundlach Optical Company in partnership with three other Rochester optical workers: John Zellweger, Henry H. Turner and John C. Reich (Figures 36 and 37). The new firm produced microscope lenses, bodies, and other optical apparatus. A new model of microscope, the “Nonpareil” (Figure 17) was evidently manufactured for Gundlach Optical by the Rochester business of Yawman & Erbe (Figures 37, 38, and 39). Other businesses were contracted to distribute Gundlach Optical apparatus, including Schmidt & Kaelber in Rochester and Meyrowitz Brothers in New York City (Figures 38 and 40).

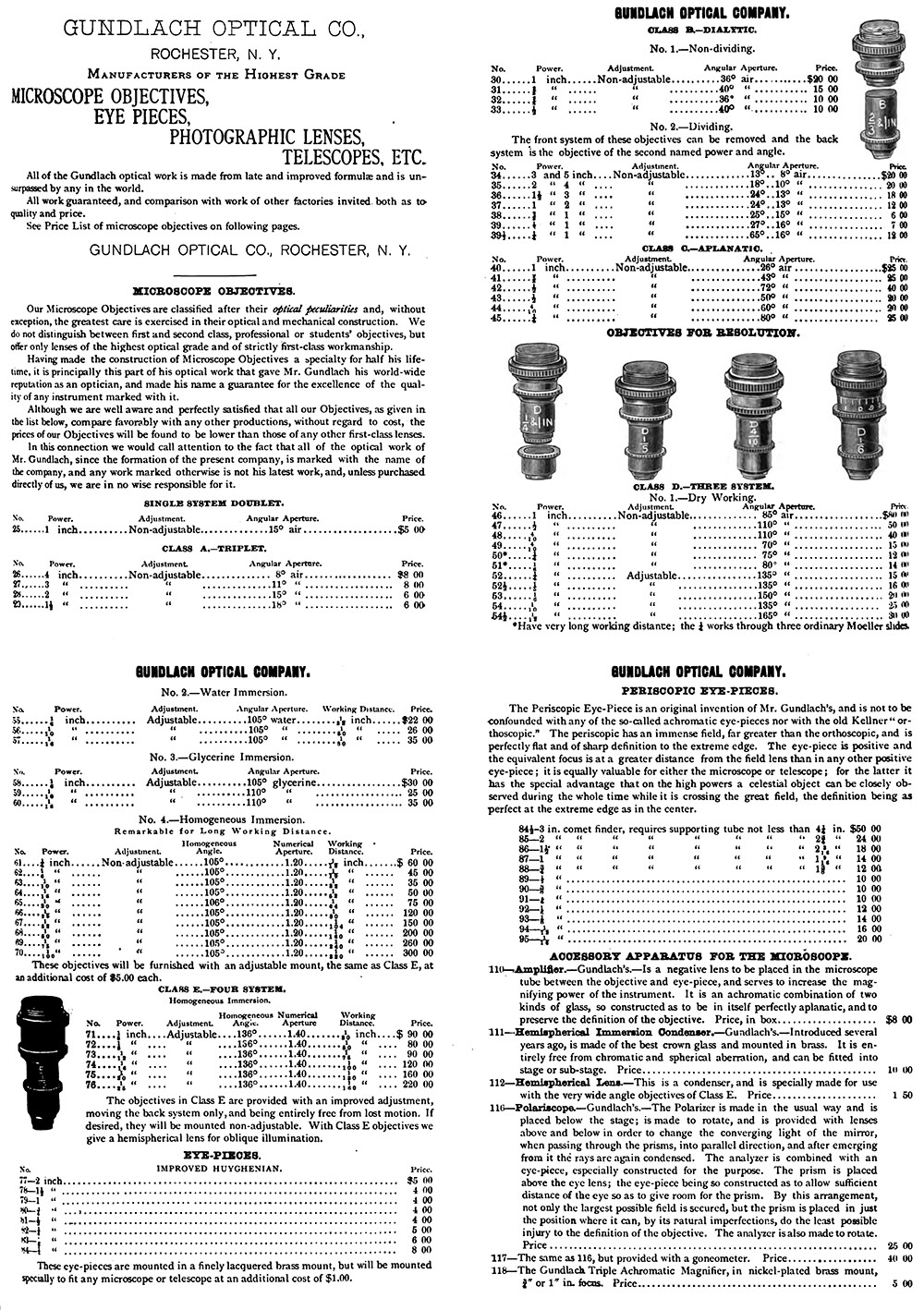

From an 1888 essay in The Industries of the City of Rochester: “The Gundlach Optical Company, Manufacturers of the Highest Grades of Microscopes, Objectives of All Kinds, Photographic Lenses, Telescopes, Eye Pieces, etc. - No, 75 Stone St.

The Gundlach Optical Company, organized in 1883, is composed of Messrs. Ernst Gundlach, John Zellweger, Henry H. Turner and John C. Reich, experienced and competent optical instrument and appliance manufacturers. Occupying one floor at No. 75 Stone street, and employing a large number of specially trained artisans, besides a splendid complement of the finest scientific machinery and apparatus, the company is prepared to fill, in the best manner and at short notice, all orders for superior work and appliances in their line, comprising microscopes of every degree of power, and of the highest grades, every variety of object glasses, telescopes, eye pieces, photographic lenses, and all special optical work. The rectigraphic lens for the use of photographers, herewith illustrated, is confessedly of the best class, and the only lens of that grade made in this country, patrons of this house thereby saving the duty imposed upon the importation of this description of goods, besides encouraging American manufactures. The company say of this lens: ‘Although the manufacture of photographic lenses is with us a comparatively late departure, yet the splendid qualities of the rectigraphic (it being constructed on a principle superior to that employed in the construction of any other photographic lens in the market) have won for it, in the short time it has been before the photographic public, a well recognized place in the front rank of photographic objectives, and our sales of it during the past year have far surpassed our greatest expectations. The rectigraphic possesses all the qualities required to make it equally valuable for either landscape or portrait work. For the latter purpose we recommend especially the large sizes, from No. 4 up. When used with the modern dry plate, they will equal the best portrait lens in rapidity, while, with their full opening, they have wonderful depth and microscopic sharpness. The rectigraphic is superior to any lens in the market in flatness of field, and is the only one that can be focused sharp at the extreme edge of the field, being free from astigmatism. Each lens is supplied with a set of diaphragms in a morocco case’.

In addition to the rectigraphic the company makes several other styles of photographic lenses. Their perigraphic lens is the only instantaneous wide angle lens in the market, and is destined to be of great value to, and very popular with, photographers. They also make a lens of extreme wide angle for use in confined situations. All these lenses come in sizes varying from twelve-sixteenths of an inch to three inches. They are fully indorsed by leading photographic artists of Rochester, New York city and elsewhere.

This company is also deserving of great credit for the fact that they are the first and only firm in the United States to give the scientific public the benefit of microscope objectives, made from the celebrated ‘new’ or apochromatic glass, made in Germany, about which so much has been written in the various journals of the day. It may safely be said that the work of the Gundlach Optical Company has done much to give the city of Rochester a high standing in the commercial world for the manufacture of the best grade of scientific instruments”.

The firm exhibited at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The American Amateur Photographer reported, “One of the most notable exhibits at the World's Fair was that of the Gundlach Optical Company of Rochester, N.Y., a company which ranks among the leading manufacturers of optical instruments of the world. Three awards were made to this company for the excellence of their goods. The business had a very modest start about ten years ago, with the optical work of Mr. Ernst Gundlach as a basis. From Mr. Gundlach the firm took its name, and he is still connected with it as consulting optician, while the firm proper consists of Henry H. Turner, John Zellweger, and John C. Reich. Microscopic objectives were the first articles manufactured, but the firm was brought into especial prominence by the superb line of photographic lenses which they originated and placed on the market. These lenses are of peculiar construction, and are protected by letters patent. They are so constructed as to eliminate to a great degree the defects which are inherent in all photographic lenses. In addition to this they are so constructed that either the front or back combination can be used as a separate objective, and a longer focus thus obtained than the combined objective gives. In this way lengths of focus can be secured varying as 2, 3, and 4. A year or two ago the firm added the manufacture of portable telescopes and microscope stands to their business, and at once took a prominent place in both these lines. In the microscope department they received two awards, being the only firm in this country to receive any awards in this line. The microscopes embrace a wide range of instruments, and are all made on the most approved models and with the greatest attention to detail and excellence of workmanship. The portable telescopes are also receiving, deserved recognition, as they are of the highest optical excellence, and mechanically have many new features for portable instruments. They are made in size from 2 1/2 inches aperture up. Many are in use in you: parts of this country, while the company is preparing to fill a European order”.

As noted in the above paragraph, Ernst Gundlach had become a consulting partner by the early 1890s, while Turner, Zelleweger, and Reich did the hard work of running the company. Their contract allocated Gundlach a royalty for use of his name, but he and his partners soon battled over these payments. Gundlach angrily resigned from the partnership in 1894, then sued his former partners over the company’s use of his name.

These legalities were summarized in 1896: “Litigation Over the Use of the Name of Gundlach in the Optical Business. Rochester, N.Y., May 9 - Ernest Gundlach, the optician and inventor, has just begun an action against the Gundlach Optical Co., demanding that the company be restrained from the further use of his name. Mr. Gundlach has achieved a high reputation, both in this country and in Europe, as an expert in the science of optics and inventor of various optical instruments. For seven years he was a manufacturer of optical goods in Berlin, Germany, doing business under the style of E. Gundlach. In 1871 he came to this country and went into the business of manufacturing optical goods at Hackensack, N.J. Five years later Bausch & Lomb, of this city, induced him to take charge of their exhibit at the Centennial exhibition. He remained with Bausch & Lomb for over two years, during which time he did not manufacture in his own name; but his inventions, which were used by the firm, were stamped ‘E. Gundlach’.

After severing his connection with Bausch & Lomb, Mr. Gundlach commenced to do business on his own responsibility, having his place of business on St. Paul, St., eventually going into partnership with three men, named John Zellweger, John C. Reich and Henry H Turner. An agreement was drawn up, whereby these three were to put in $600 apiece, while Gundlach was to furnish as his contribution to the partnership, his instruments and machinery. This was the commencement of the present corporation known as the Gundlach Optical Co.

Under this agreement the partnership continued for nine years, Mr. Gundlach having charge of the theoretical, experimental and scientific part of the business. Becoming dissatisfied with his share of the profits, he expressed a desire to retire from partnership. New articles were then drawn up, whereby the old partnership was dissolved and a new one formed under the same name. By this Gundlach assigned to the partnership all his patents, and was to receive as his share of the net profits 12 1/2 percent, the royalty to be paid in weekly payments of not less than $30. Under this agreement Gundlach did not have to devote his whole attention to the business, but was to give the company, at any time they wished, the benefit of his technical knowledge.

In June, 1892, Gundlach began action against the optical company, claiming that they had got behind in their payments to him, and demanding an accounting. The other partners at the same time commenced a counter-action against the inventor, claiming he had violated his agreement with them. These suits were finally settled and never brought to trial.

Two years later Mr. Gundlach and the other partners had another disagreement, which resulted in his withdrawing from the partnership and receivings re-assignment of the patents included in the articles of agreement, but the company continued to do business under the style of Gundlach Optical Co. and were incorporated under this name a few months later.

Mr. Gundlach, it appears from the moving papers, has since started in the optical business for himself once more and has a new photographic camera which he thinks will revolutionize things and which he is desirous of placing on the market. In fact he has formed a company known as the Gundlach Photo-Optical Co., but finds himself handicapped by the presence in the field of another Gundlach Optical Co. The courts are asked to enjoin the defendants from the further use of the plaintiff's name both in the manufacture and sale of their optical goods or as a part of their corporate name”.

Ernst Gundlach obviously lost his lawsuit, as the Gundlach Optical Company continued to manufacture microscopes, cameras, and other optical apparatus into the twentieth century (Figures 18 and 19). In 1902, Gundlach Optical became the Gundlach-Manhattan Optical Company, as reported, “We have been advised of the incorporation, on August 6th, of the Gundlach-Manhattan Optical Company, with a capital of $600,000. This corporation takes up the entire plant and business of the Gundlach Optical Company of Rochester, N.Y., and the machinery, stock, patents, and business of the Manhattan Optical Company of New York, Cresskill, N.J. The plant of the latter company has been closed, and all the effects are being removed to the Rochester plant of the new corporation, where all of its product will be manufactured in the future”.

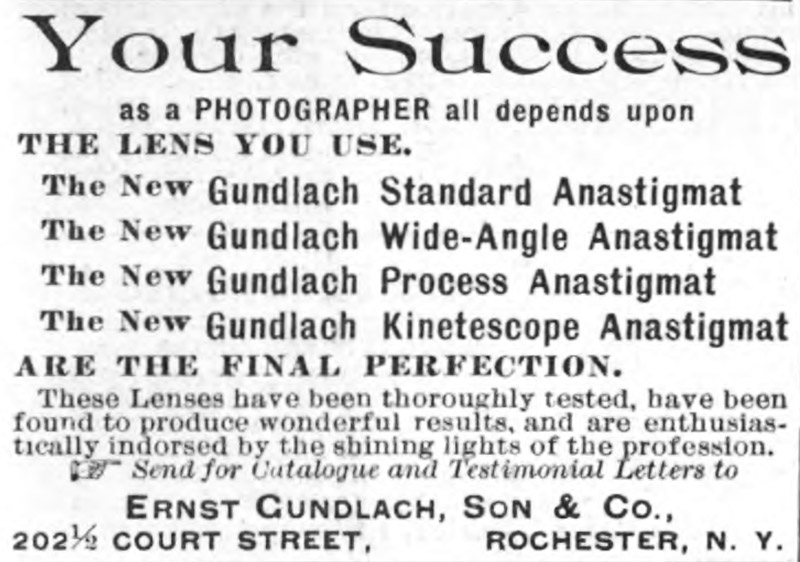

Undaunted, Gundlach began another optical company, first named "The Gundlach Photo-Optical Company", then changed ca. 1898 to “Ernst Gundlach, Son & Company” (Figures 43-45). It was out of business by the end of 1898, as reported, “Firm of Ernst Gundlach, Son & Co. in the Sheriff's Hands, Rochester, N.Y., Oct. 27 - Judgments have been docketed against Ernst Gundlach, Son & Co., opticians, 202 Court St. The works were closed yesterday by Deputy Sheriff Vick”.

Gundlach then moved to Chicago to supervise the optical department of the Vive Camera Company (Figure 46). He continued to create innovative lenses, such as noted in 1900, “Ernst Gundlach, the pioneer lens maker, has in preparation a new lens which will fill a long-felt want in the present lens system. It is an instantaneous wide angle, working at f/10, and fast enough for ordinary instantaneous work, yet giving a much wider angle than the symmetrical or rectilinear lenses. He is also about to produce a convertible anastigmat of two, three or four lenses, making three, five or ten different focal lengths. The new lenses will shortly be placed on the market by the Vive Camera Company of Chicago, for whom Mr. Gundlach is chief of the lensmaking department”.

In addition to optics, Gundlach explored other fields. In 1904, he received a patent for a telephone receiver, “The last patent for present consideration is one granted to Ernst Gundlach, of Berwyn, Ill., for a telephone receiver and assigned to the American Telephone & Telegraph Company. This receiver is built upon the same general lines as one patented by the same inventor some six months since, and has for its most novel features a spring device for mechanically straining the diaphragm in a direction opposed to the magnetic pull, and the provision of a pole piece mounted at the center of the diaphragm. The core of soft iron but partially fills the spool aperture, the armature extending loosely within the upper portion of it. Great sensitiveness is claimed for this type of receiver.” (Berwyn is a suburb of Chicago).

Soon afterward, Ernst and his family returned to Berlin. The November 5, 1905 issue of Der Mechaniker reported under new businesses: “Ernst Gundlach & Sohn, Elektrotechniker, Berlin”.

In May, 1906, Gundlach filed for a patent on a “spherically, chromatically and astigmatically corrected lens”, “Sphärisch, chromatisch und astigmatisch korrigiertes, aus je zwei verkitteten Linsen bestehendes Gauß-Objektiv mit einander zugewandten Kittflächen. E. Gundlach, Berlin. 31. 5. 06”.

Ernst Gundlach died in Berlin in 1908.

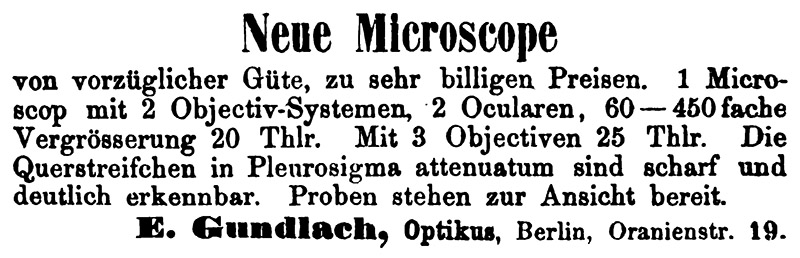

Figure 20.

1865 advertisement, from “Annalen der Physik und Chemie”. Gundlach wrote that he began making his own microscopes in Berlin during 1864.

Figure 21.

An 1867 advertisement. Gundlach was awarded a medal for his microscopes and glycerine-immersion lenses at the 1867 Paris International Exposition. From “Pharmazeutische Zentralhalle für Deutschland”.

���

���

Figure 22.

In 1870, John Winspear became sole distributor of Gundlach lenses for England. Advertisement from the January, 1870 issue of “The Monthly Microscopical Journal”.

Figure 23.

Within a year, Gundlach had made a deal for Charles Baker, of London, to be his sole English distributor. Advertisement from the January, 1871 issue “The Popular Science Review”.

Figure 24 (below). Ernst Gundlach’s 1870 price list, as reproduced in Heinrich Frey’s 1871 “Das Mikroskop und die Mikroskopische Technik”.

Figure 24.

Ernst Gundlach’s 1870 price list, as reproduced in Heinrich Frey’s 1871 “Das Mikroskop und die Mikroskopische Technik”.

Figure 25.

Ernst Gundlach and his family arrived in New York, USA, on August 22, 1872, aboard the “S.S. Nerissa”. His occupation was listed as “mechanic”. Notably absent from the record is his daughter Emilia, who was listed in the 1861 census of England, and would have been 12 years old.

Figure 26.

Ernst Gundlach kept busy with attempts to earn money. In November, 1873, he patented an improved form of laundry mangle (i.e., a wringer to press water from wet laundry)

Figure 27.

An 1878 advertisement announcing that Ernst Gundlach was manufacturing microscopes and telescopes under his own name, having separated from Bausch and Lomb on March 18, 1878.

Figure 28.

Side-by-side advertisements from Ernst Gundlach, who announced he new objective lenses, and Bausch & Lomb, who included a letter from Gundlach about leaving that firm, and announced that they had retained all of the patents that Gundlach was awarded while in their employ.

Figure 29.

An 1878 advertisement, from “The Naturalists’ Directory”.

Figure 30.

Between 1879 and 1884, Lewis R. Sexton distributed Ernst Gundlach’s lenses.

Figure 31.

1879 advertisements from “The American Journal of Microscopy and Popular Science”. Notably, Giering & Co. advertised in early 1879 that they were the “sole proprietors and manufacturers of the latest improved Gundlach microscopes”, yet by the end of the year Gundlach was not mentioned in their advertisement, while the same page of the magazine included an advertisement that Gundlach’s microscopes should be purchased directly from him. The suggests that Giering & Co. briefly manufactured microscopes for Gundlach, and that part way through 1879 he opted for another source.

Figure 32.

1883 note from “The Microscope”. Although Sexton supposedly still had sole distribution rights to Gundlach’s lenses, other entities had separate rights to distribute his microscope bodies. The various distributors and retailers of Gundlach’s microscopes mean that other firms’ names may be attached to instruments.

Figure 33.

January, 1884 advertisement for Gundlach’s lenses and “apparatus” from L.R. Sexton.

Figure 34.

August, 1884 notice that Lewis Sexton has sold his stock of Gundlach lenses to Bausch & Lomb. There must have been a considerable number of lenses involved, as Bausch & Lomb advertised their Gundlach lenses for several years afterward (e.g. Figure 35).

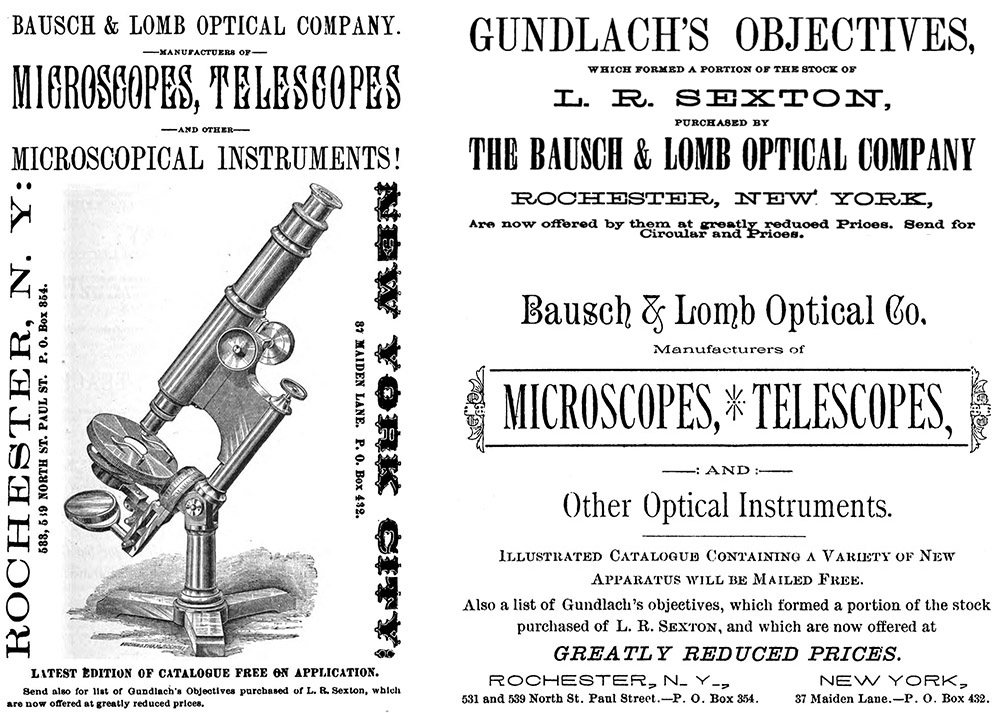

Figure 35.

Three 1884/1885 advertisements from Bausch & Lomb, stating that they were selling Gundlach lenses which had been acquired from L.R. Sexton just before his death in August, 1884. Thus, it would not be uncommon to find mid-1880s Bausch & Lomb microscope stands that were originally sold with Gundlach lenses, many years after Gundlach had left Bausch & Lomb!

Figure 36.

In 1883, Ernst Gundlach formed the “Gundlach Optical Company” in partnership with John Zellweger, Henry H. Turner and John C. Reich. Advertisement from the 1884 “Rochester Directory”.

Figure 37.

Around 1884, The Gundlach Optical Company began producing the “Nonpareil” microscope stand, presumably from Ernst Gundlach’s design. The company evidently contracted with Yawman & Erbe to produce the bodies. Examples of this model are known to have either or both names on them (see Figure 17, above). Although the differences might be due to interpretations by the artists, the engravings suggest that Nonpareil microscopes were produced with two different shapes of the foot and two different mirror mounts (see also Figure 40, below).

Figure 38.

1884 advertisements from “The Rochester Directory”. Yawman & Erbe evidently manufactured “Nonpareil” microscope bodies for the Gundlach Optical Company (see Figures 17 and 37), and Schmidt & Kaelber were then sole agents for distribution of this microscope model.

Figure 39.

A page from the list of exhibitors at the 1884 Annual Soiree of the American Society of Microscopists, which includes each exhibitors’ microscopes. Note that The Gundlach Optical Company, Philip Yawman, Gustave Erbe, and Schmidt & Kaelber all presented microscopes that were manufactured by Yawman & Erbe. The “Gundlach’s Physician’s” microscope displayed by John G. Allen was presumably a model that predated the contract with Yawman & Erbe.

Figure 40.

By 1886, The Gundlach Optical Company had contracted with additional distributors. These 1886 advertisements from the Meyrowitz Brothers stated that they were sole distributors for New York City and vicinity.

Figure 41.

1890 price list for the Gundlach Optical Company’s microscope lenses and accessories. From the Charles Truax & Company’s “Price List of Physicians' Supplies”.

Figure 42.

While the Gundlach Optical Company continued to manufacture microscope lenses and bodies, their main focus was on photographic apparatus. This advertisement is from the 1889 “International Annual of Anthony's Photographic Bulletin”.

�

Figure 43.

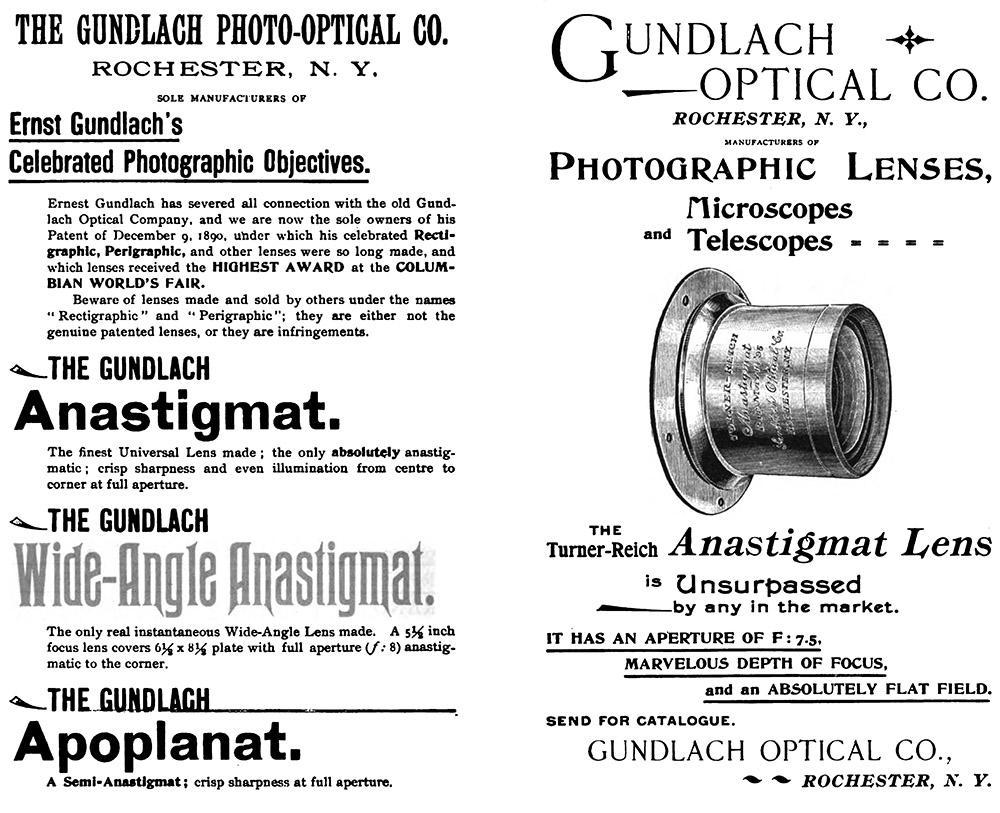

Ernst Gundlach split from his partnership in 1895, and formed a new business, “The Gundlach Photo-Optical Company”. These two advertisements from the competing companies appeared in the 1895 “American Annual of Photography”.

Figure 44.

Ernst Gundlach renamed his business as “Ernst Gundlach, Son & Company” ca. 1896. They were out of business by the end of 1898. This advertisements is from the July 16, 1898 issue of “Scientific American”.

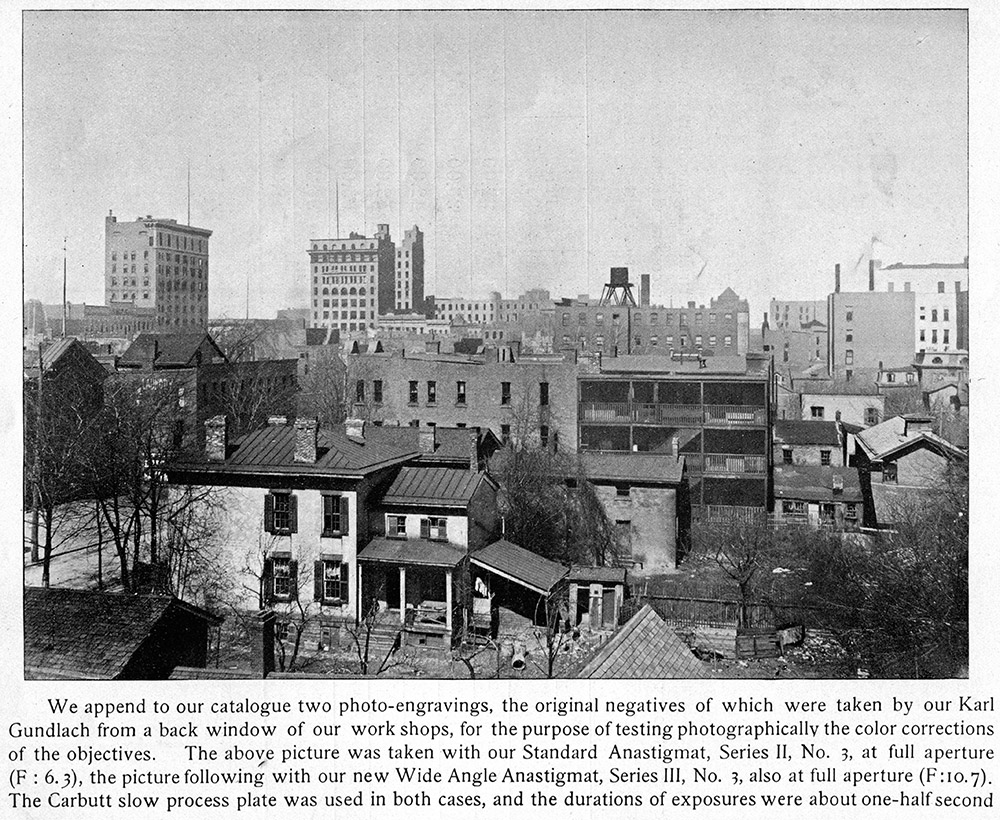

Figure 45.

A photograph of Rochester, New York, taken by Ernst Gundlach’s son, Karl, from the premises of Ernst Gundlach, Son & Company. From their 1898 catalogue of photographic lenses.

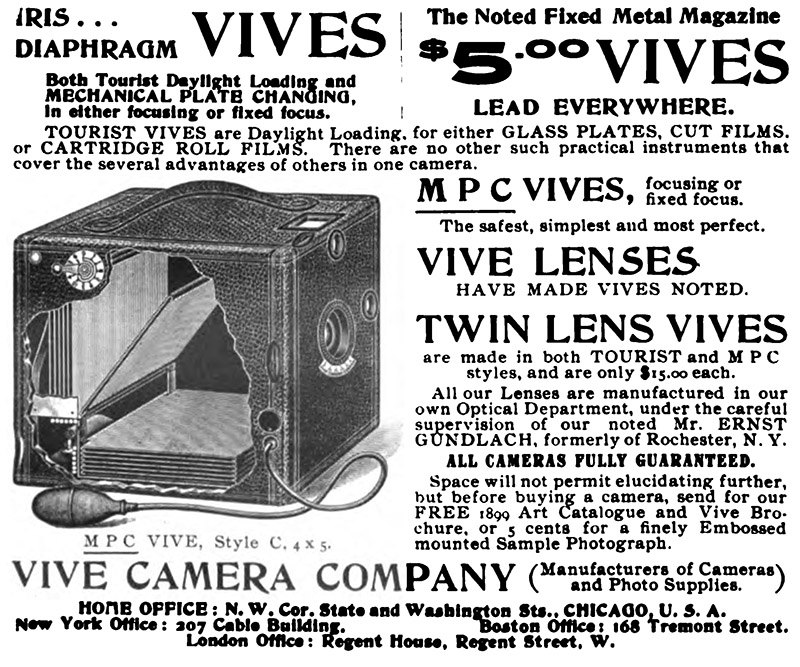

Figure 46.

Gundlach moved to Chicago ca. 1899, to head up the optical department of the Vive Camera Company.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Timo Mappes and Allen Wissner for permission to use images from their on-line microscope collections, and to Joe Zeligs for providing additional data.

The American Amateur Photographer (1893) Optical goods at the Exposition, Vol. 5, page 590

The American Annual of Photography (1895) Advertisements from The Gundlach Photo-Optical Company and the Gundlach Optical Company, Volume 10

The American Journal of Microscopy and Popular Science (1878) Advertisements from Ernst Gundlach and Bausch & Lomb, July issue, page 2

The American Journal of Microscopy and Popular Science (1879) Advertisements from Ernst Gundlach, L.R. Sexton, Giering & Co., and the Industrial Publication Co., Vol. 4

The American Journal of Microscopy and Popular Science (1880) Vol. 5, pages 222-225

The American Monthly Microscopical Journal (1880) Advertisement from L.R. Sexton, Vol. 1, September issue

The American Monthly Microscopical Journal (1881) Vol. 2, page 58

The American Monthly Microscopical Journal (1881) Vol. 2, page 58

The American Monthly Microscopical Journal (1886) Advertisements from Gundlach Optical and Meyrowitz Brothers, Vol. 7

The American Monthly Microscopical Journal (1886) Advertisements from Bausch & Lomb, Vol. 7

The American Naturalist (1873) Microscopy in New Jersey, Vol. 7, page 119

The American Naturalist (1879) Ernst Gundlach, Vol. 13, page 797

Annalen der Physik und Chemie (1865) Advertisement from Ernst Gundlach

Berliner Klinische Wochenschrift (1866) Advertisement from Ernst Gundlach, Vol. 3, page 436

The Botanical Gazette (1878) Advertisement from Ernst Gundlach, Vol. 3, August issue

Botanische Zeitung (1866) Advertisements from Ernst Gundlach, Vol. 24, pages 64 and 348

Camera (1902) note on the formation of the Gundlach-Manhattan Optical Company, Vol. 6, page 324

Camera Craft (1900) Vol. 2, page 260

Charles Truax & Co. (1890) Price List of Physicians' Supplies

The Dental Register (1873) Microscopic objectives, Vol. 27, pages 312-314

Dippel, Leopold (1882) Das Mikroskop und Seine Anwendung, Part 1, F. Vieweg und Sohn, Braunschweig, pages 477-483

The Electrical World and Engineer (1904) Telephone receiver, Vol. 43, page 1199

England census (1861) accessed through ancestry.com

Ernst Gundlach, Son & Co. (1898) Descriptive Catalogue and Price-List of Photographic Lenses, Rochester, New York

Frey, Heinrich (1871) Das Mikroskop und die Mikroskopische Technik, W. Engelmann, Leipzig, pages 386-389

Grave record of Lewis R. Sexton (1884) accessed through https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/146246555/lewis-r_-sexton

Gundlach, Ernst (1881) Working-distance and its relations to focal length and aperture, The American Monthly Microscopical Journal, Vol. 2, pages 32-33

Gundlach, Ernst (1884) Aperture and working distance, The Microscope, Vol. 4, pages 246-248

Gundlach, Ernst (1885) The examination of objectives, The Microscopical Bulletin, Vol. 2, pages 14-15 and 18-19

Gundlach, Ernst (1900) How to test and select a high-grade photographic lens, Camera Craft, Vol. 2, pages 101-115

The Industrial Advance of Rochester (1884) Schmidt & Kaelber, National Publishing Co., Rochester, page 146

The Industries of the City of Rochester (1888) The Gundlach Optical Company, Elstner Publishing Company, Rochester, page 169

International Annual of Anthony's Photographic Bulletin (1889) Advertisement from the Gundlach Optical Company, page 37

International Annual of Anthony's Photographic Bulletin (1900) Advertisement from the Vive Camera Company, page 53

Jeweler’s Circular and Horological Review (1896) Litigation over the use of the name of Gundlach in the optical business, Vol. 32, pages 9-10

Jeweler’s Circular and Horological Review (1898) Firm of Ernst Gundlach, Son & Co. in the Sheriff's hands, Vol. 37, page 11

The Journal of Mycology (1885) Advertisements from Bausch & Lomb, Vol. 2

Kingslake, Rudolf (1978) Ernst Gundlach: nineteenth-century pioneer optician, History of Photography, Vol. 2, pages 361-364

Lens (1873) Gundlach’s objectives, Vol. 2, page 52

Mappes, Timo (2008) The microscopes for science and medicine by Ernst Gundlach Berlin 1865-1872, Journal of the Microscopical Historical Society, Vol. 16, pages 148-161

Der Mechaniker (1905) Neue Firmen, Vol. 13, page 256

La Médecine à l'Exposition Universelle (1867) pages xii and 25

The Microscope (1883) Vol. 3, page 191

The Microscope (1884) Vol. 4, pages 190, 210, and 253

The Microscope (1884) Advertisement from Gundlach Optical Company, Vol. 4

The Microscope (1885) Advertisements from Bausch & Lomb, Vol. 5

The Microscope (1886) Advertisements from Gundlach Optical Company and Meyrowitz Brothers, Vol. 5

The Microscopical Bulletin (1884) Vol. 1, page 44

Monthly Microscopical Journal (1870) Advertisement from J.E. Winspear, Vol. 3, January issue, advertisements page 5

The Naturalists’ Directory (1878) Advertisement from Ernst Gundlach

Odontographic Journal (1884) Vol. 5, page 104

Padgitt, Donald L. (1975) A Short History of the Early American Microscopes, Microscope Publications Ltd., London, pages 83-105, 118-120, and 139-140

Passenger list of the Nerissa (1872) August 22, accessed through ancestry.com

Pharmazeutische Zentralhalle für Deutschland (1867) Advertisement from Ernst Gundlach, Vol. 8, pages 388 and 403

The Popular Science Review (1871) Advertisement from C. Baker, January issue, advertiser section

Proceedings of the American Society of Microscopists (1882) Ernst Gundlach, Vol. 5, pages 45-46

Proceedings of the American Society of Microscopists (1884) The Annual Soiree of the Society, in connection with the Rochester Academy of Sciences, Vol. 6, pages 234-249

Rapports du Jury International de l'Exposition Universelle (1867) Microscopes, pages 471-472

Reithmeier, Gordon P. (2000) Microscopes by Bausch & Lomb Optical Co., Rochester, N.Y., 1876-1896, Gemmary, Fallbrook, California

Rochester Directory (1884) pages 604, 870, 872, and 893

Scientific American (1898) Advertisement from Ernst Gundlach, Son, and Company, Vol. 79, page 48

Scientific Opinion (1870) Gundlach’s objectives, Vol. 3, page 416

Shilling, Donovan A. (2015) Made in Rochester, Shilling, Rochester, pages 92-93 and 272

Transactions of the American Microscopical Society (1881) Vol. 3, page 86

U.S.A. census records, accessed through ancestry.com

Ward, R.H. (1877) Microscopy at the American Exhibition, Monthly Microscopical Journal, Vol. 17, pages 25-30

Zeitschrift der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Mechanik und Optik (1907) page 216