Georg Johann Oberhäuser / Georges Jean Oberhaeuser, 1798-1868

Friedrich Edmund Hartnack, 1826-1891

Adam Prażmowski, 1821-1885

by Brian Stevenson

last updated June, 2025

The Parisian optical business that was founded by Georg Oberhaeuser made significant impacts on microscope development. These included popularization of Martin’s drum pattern as an inexpensive yet stable body form, development of the horseshoe-footed “continental” stand, and water-immersion objective lenses.

Oberhaeuser began his business in approximately 1830, after working since his early teens for instrument makers in Würzburg and Paris. In 1854, he formed a partnership with his assistant Hartnack, then retired shortly afterwards. Hartnack was forced to leave France in 1870, at the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War, whereupon he established a business in Potsdam (near Berlin). He continued the Paris business as Hartnack & Company then, later, Hartnack and Prażmowski. Prażmowski took sole ownership of the Paris branch in 1878, then passed it on to his employees Bézu and Hausser in 1883 (details of the lives and works of Bézu, Hausser & Co. are presented in a separate essay on this site). Hartnack’s Potsdam business continued after his death until well into the 1900s.

As much as possible, his essay is drawn from original documents. Those contemporary sources revealed information that was heretofore not widely known. Of great importance was a memorial of Oberhaeuser’s life, written by Lorenz Strebel, the schoolmaster of Oberhaeuser’s home town, who knew the optician and drew from personal knowledge. Legal records, such as descriptions of patents and partnerships, shed light on relationships between Oberhaeuser, Hartnack, Prażmowski, and others.

Those contemporary records indicate that some widely-held assumptions about the Oberhaeuser-Hartnack-Prażmowski business are not accurate, such as certain dates and Oberhaeuser’s business relationships with two other men, Bouquet and Trécourt. Some important revelations:

![]() Oberhaeuser moved to Paris in 1816, whereupon he worked first for the optical businesses of Henri Gambey, then moved on to work in a shop owned by one of the Rochette family.

Oberhaeuser moved to Paris in 1816, whereupon he worked first for the optical businesses of Henri Gambey, then moved on to work in a shop owned by one of the Rochette family.

![]() Oberhaeuser began his independent optical business in approximately 1830. It is known that his shop was located at 19 Place Dauphine in January, 1832, and so it is likely that he operated from that site at the outset.

Oberhaeuser began his independent optical business in approximately 1830. It is known that his shop was located at 19 Place Dauphine in January, 1832, and so it is likely that he operated from that site at the outset.

![]() Oberhaeuser worked for a period of time with an optician named Bouquet, as microscopes are known that bear both names. The known times of his other business dealings mean that this would have taken place during the early 1830s. But Oberhaeuser appears to have maintained an individual business, as an 1832 patent was assigned in his name only, and he produced surveying instruments under his own name in 1833. By 1835, Oberhaeuser’s business was in competition against Bouquet.

Oberhaeuser worked for a period of time with an optician named Bouquet, as microscopes are known that bear both names. The known times of his other business dealings mean that this would have taken place during the early 1830s. But Oberhaeuser appears to have maintained an individual business, as an 1832 patent was assigned in his name only, and he produced surveying instruments under his own name in 1833. By 1835, Oberhaeuser’s business was in competition against Bouquet.

![]() In about 1833, Oberhaeuser met Achille Trécourt, who was a clerk in the French Ministry of War, and he helped Oberhaeuser obtain work in maintaining the Ministry’s technical equipment. Oberhaeuser held the position of “Ingénieur Opticien du Dépôt de la Geurre” throughout his career, and passed the office on to Hartnack. I did not find evidence to suggest that Trécourt was a craftsman; it is likely that his role was to help with finances and make connections with the government and scientific communities.

In about 1833, Oberhaeuser met Achille Trécourt, who was a clerk in the French Ministry of War, and he helped Oberhaeuser obtain work in maintaining the Ministry’s technical equipment. Oberhaeuser held the position of “Ingénieur Opticien du Dépôt de la Geurre” throughout his career, and passed the office on to Hartnack. I did not find evidence to suggest that Trécourt was a craftsman; it is likely that his role was to help with finances and make connections with the government and scientific communities.

![]() Oberhaeuser and Trécourt formed a partnership around 1835. In that year, they produced microscope lenses made of diamond, sapphire, and ruby for the French Academy. In 1837, the partners were awarded a patent for a microscope design, having a body that revolves around a fixed stage (Figure 6). Various records suggest that the partnership ended by 1839.

Oberhaeuser and Trécourt formed a partnership around 1835. In that year, they produced microscope lenses made of diamond, sapphire, and ruby for the French Academy. In 1837, the partners were awarded a patent for a microscope design, having a body that revolves around a fixed stage (Figure 6). Various records suggest that the partnership ended by 1839.

![]() Edmund Hartnack began working for Oberhaeuser in 1847.

Edmund Hartnack began working for Oberhaeuser in 1847.

![]() Oberhaeuser took Hartnack as a partner in 1854, then retired from active work. However, the business operated as “Oberhaeuser and Hartnack” until 1859.

Oberhaeuser took Hartnack as a partner in 1854, then retired from active work. However, the business operated as “Oberhaeuser and Hartnack” until 1859.

![]() Hartnack became the sole owner during 1859, and the firm became simply “Hartnack”.

Hartnack became the sole owner during 1859, and the firm became simply “Hartnack”.

![]() Hartnack formed “Hartnack et Cie.” upon his departure from Paris in 1870. The business became “Hartnack & Prażmowski” in 1873, then sole ownership was transferred to Prażmowski in 1878.

Hartnack formed “Hartnack et Cie.” upon his departure from Paris in 1870. The business became “Hartnack & Prażmowski” in 1873, then sole ownership was transferred to Prażmowski in 1878.

Some useful dates for determining the age of Oberhaeuser-Hartnack-Prażmowski microscopes:

ca. 1830: Oberhaeuser left Rochette and established his own business.

ca. 1831: Collaboration of Oberhaeuser and Bouquet.

1832: Oberhaeuser was established at 19 Place Dauphine by January, 1832. It is likely that he started his shop at that address.

ca. 1833 - ca. 1839: Partnership of Oberhaeuser and Trécourt. This was probably restricted to microscopes, as Oberhaeuser is known to have made surveying equipment during this period, under his name only.

ca. 1840: Microscope number 638 is signed by only Oberhaeuser

1848: Pieter Harting purchased a large microscope with serial number 1550 from Oberhaeuser.

1850: Willem Vrolik purchased microscope number 1786 on March 7, 1850.

1855: The address of “Oberhaeuser and Hartnack” changed from 19 to 21 Place Dauphine.

1859: “Oberhaeuser and Hartnack” became “Hartnack”.

1870: Hartnack left Paris with the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War. The Paris business became “Hartnack et Cie.”, and a second operation was begun in Potsdam as “Hartnack & Co.” (and which later became simply "Hartnack").

1873: The Paris business became “Hartnack & Prażmowski”, and moved to 1 Rue Bonaparte.

1878: Hartnack and Prażmowski dissolved their Paris partnership on July 27, and that business continued as “Prażmowski”.

1883: The Prażmowski business was passed to two former employees and their backers, becoming “Bézu, Hausser et Cie”, although they continued to use Prażmowski’s name until his death in 1885.

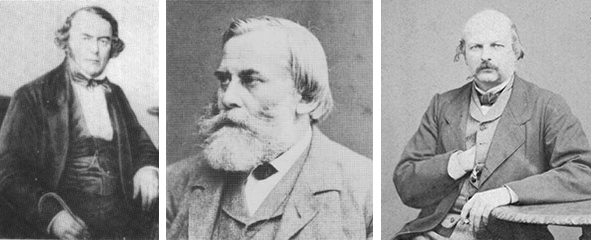

Figure 1.

Left to right: Georges Oberhaeuser, Edmund Hartnack, and Adam Prażmowski.

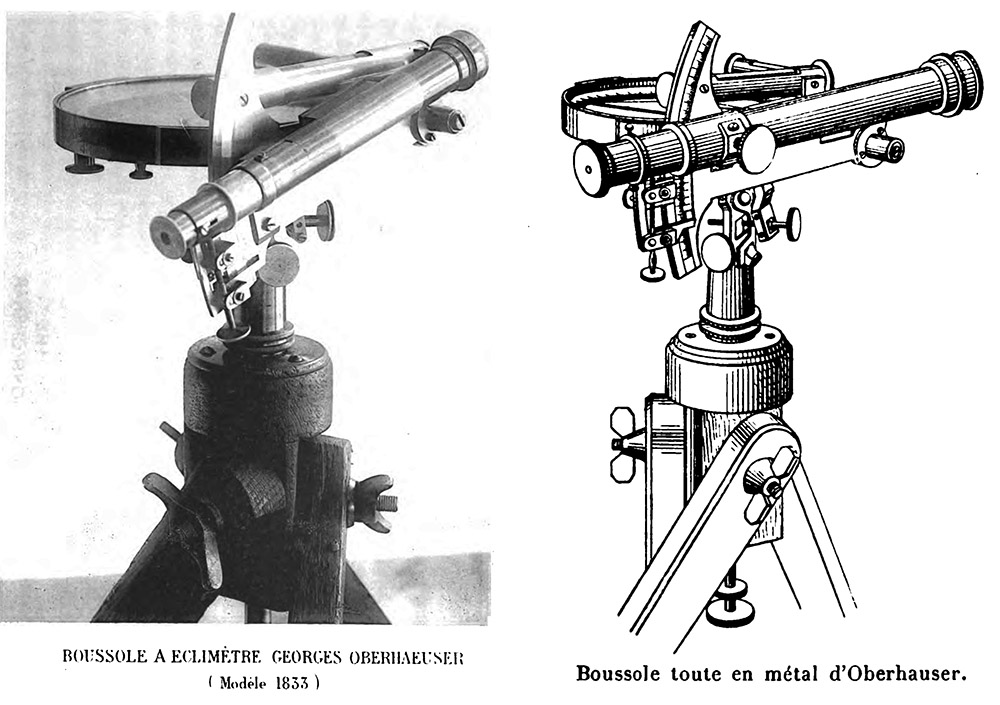

Figure 2.

One of the earliest known microscopes that was produced by Georges Oberhaeuser, a drum-style instrument that he made in collaboration with Bouquet. Oberhaeuser is credited with the popularization of the solid, yet inexpensive, drum type of microscope in the nineteenth century. Note that the inscription gives Oberhaeuser’s first name, but not that of Bouquet, suggestive of a collaboration between two businesses, rather than a formal partnership. The illustrated microscope is one of only two known examples of Bouquet and Oberhaeuser microscopes, the other having been in Alfred Nachet’s famed collection. The paucity of Bouquet and Oberhaeuser instruments is consistent with the apparent brevity of their collaboration. Adapted with permission of Albert Balasse, http://www.lecompendium.com/dossier_optique_143_microscope_bouquet_et_oberhauser/microscope_bouquet_et_oberhauser.htm.

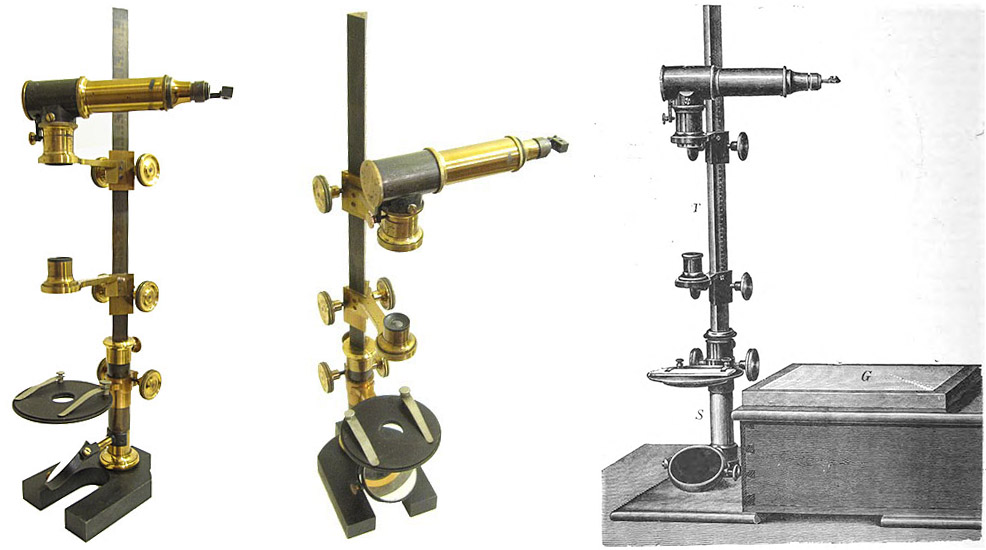

Figure 3.

Photograph and drawing of Oberhaeuser’s ca. 1833 surveying instruments, which he manufactured for the Ministry of War. A chance meeting with Achille Trécourt, who was a secretary in the Ministry, led to Oberhaeuser being appointed to first maintain, then produce, optical apparatus for the Ministries of War and the Navy.

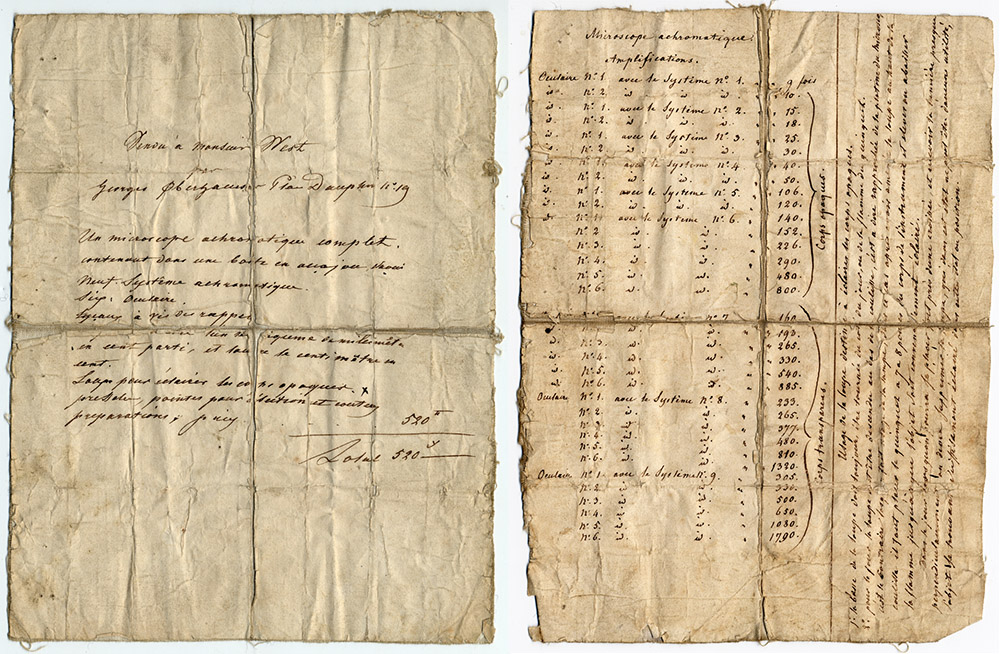

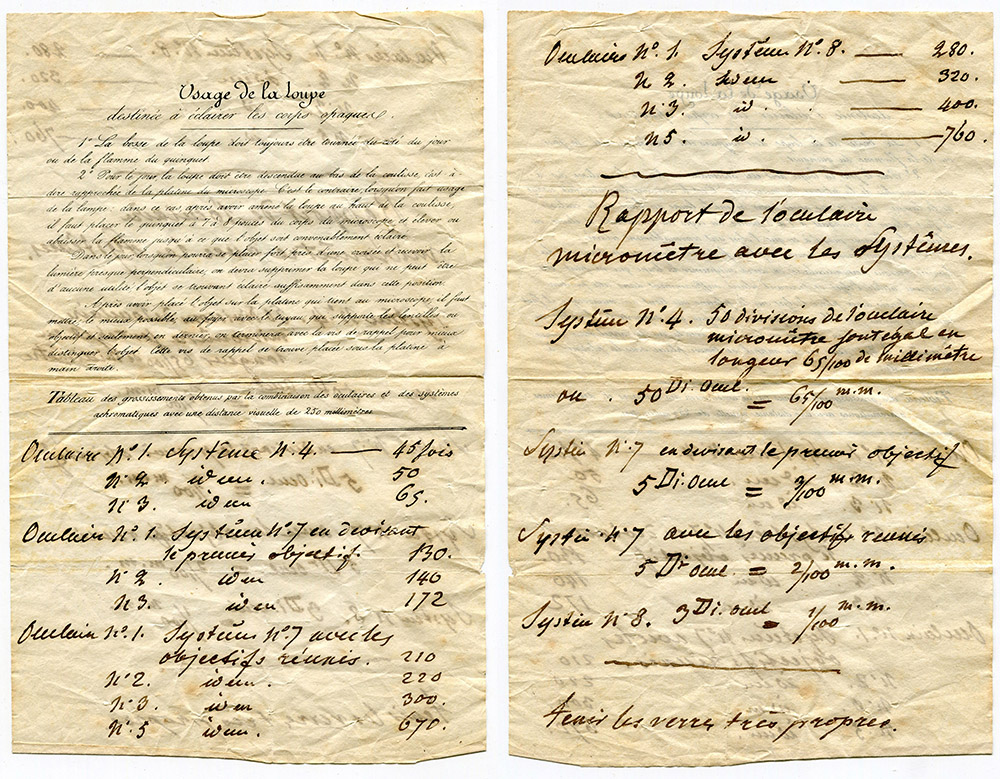

Figure 4A.

A circa 1835 small drum microscope, signed “Trécourt and Oberhaeuser, á Paris”. The center of the round base is stamped with the number "14", presumably indicating that this was produced in a batch of at least that many instruments. This set originally included 9 objective lenses and 6 ocular lenses, all of different powers. Throughout the nineteenth century, it was common for French microscope-makers to provide multiple ocular lenses, which enables rapid changes of magnification. Another, identical microscope is shown in Figure 5, below. Images adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://mhs.web.ox.ac.uk/collections-online#/item/hsm-catalogue-5870.

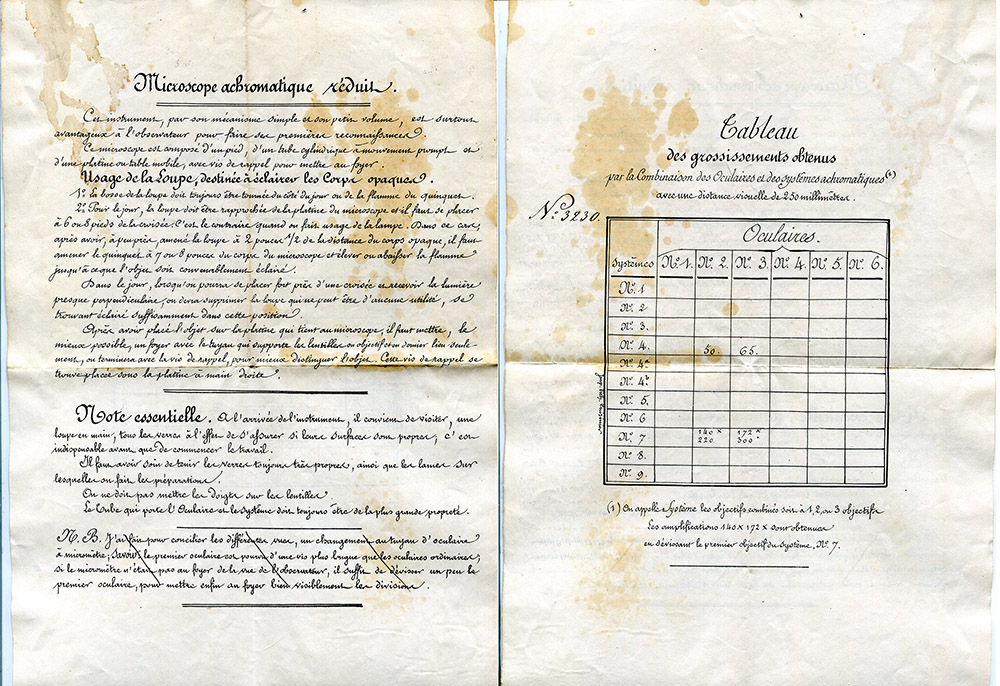

Figure 4B.

Information that originally accompanied the small microscope that is shown in Figure 4, presumably written by Oberhaeuser himself. Note that even though the microscope is signed “Trécourt and Oberhaeuser”, the bill of sale mentions only Oberhaeuser. The sheet on the right provides information on combinations of the 9 objective and 6 ocular lenses that were provided with this instrument. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://mhs.web.ox.ac.uk/collections-online#/item/hsm-catalogue-5870.

Figure 5.

Another microscope from Trécourt and Oberhaeuser, identical to the instrument shown in Figure 4, but signed "L’Ingr Chevallier, Opticien du Roi, Vis à vis le Marché aux Fleurs, a Paris". In the later years of his life, “J.G.A Chevallier ("L’Ingr Chevallier")” was known to have sold instruments from other makers. The round base and case of this microscope are marked with the number "31". Oberhaeuser is known to have produced batches of the same model at the same time, so the number "31" identifies components of a microscope that were made to fit with each other.

Figure 6A.

Five ca.1837-39 large drum microscopes by Trécourt and Oberhaeuser. The upper bodies revolve around the axis of illumination. All are engraved "Trécourt & Georges Oberhaeuser”, with Oberhaeuser’s address, “Place Dauphine No. 19, Paris”, and “Brevet d'Invention", which indicates their 1837 patent on this form of microscope. The middle example includes a horizontal body extension (with an internal mirror) and camera lucida. The microscope on the right is probably the newest of the series. Adapted with permission of Jeroen Meeusen, https://www.meeusen.com

Figure 6B.

A ca.1837-39 large drum microscope by Trécourt and Oberhaeuser, with its case and accessories. Adapted with permission of Jeroen Meeusen, https://www.meeusen.com

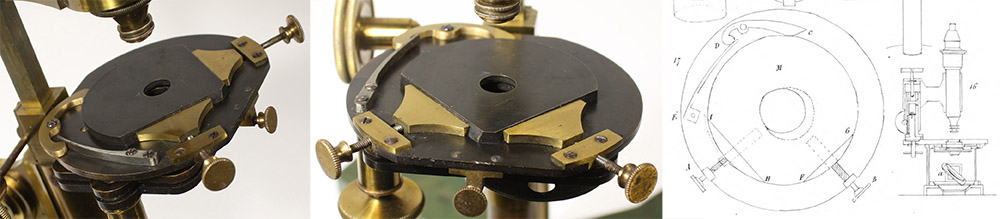

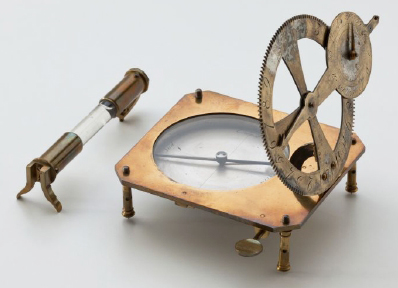

Figure 7.

Georges Oberhaeuser invented this relatively simple mechanical stage ca. 1839. The stage is moved by two thumbscrews, positioned 90 degrees from each other. A spring mechanism holds the stage in position. The two photographs show such a stage, built to fit the rectangular stage of a microscope ascribed to Charles Chevalier. Oberhaeuser’s original design fit on the circular stages of his drum microscopes. The image on the right is from Louis Mandl’s 1839 “Traité Pratique du Microscope”, where it was described as being new. Mandl’s figure also shows a diagram of Trécourt and Oberhaeuser’s patented drum microscope design (see Figures 6 and 39).

Figure 8A.

A medium-sized drum-type microscope by Oberhaeuser, serial number 733, manufactured ca. 1843. It is somewhat smaller than the large drum microscopes shown in Figures 6A and 8B (see Figure 8C). The limb is engraved "Brevet d'Invention, Microscope Achromatique, Eclairage à rayons parallèles. Diaphragme à mouvement vertical". The base is engraved, "Georges Oberhaeuser, Ingr Optn Brevete, Place Dauphine 19, Paris" and "No. 733".

Figure 8B.

Large Oberhaeuser drum microscope, serial number 794, manufactured ca. 1844. It is similar to the right-most Trécourt and Oberhaeuser microscope shown in Figure 6A, above. It is engraved, "Georges Oberhaeuser, Ingenieur Opticien, breveté, Place Dauphine, 19 Paris" and "Microscope achromatique Platine à Tourbillon. Eclairage à rayons parallèles. Diaphragme à mouvement vertical". Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Figure 8C.

Another large drum microscope by Oberhaeuser, with a differently-shaped arm. Seial number 994, ca. 1845. This example was initially sold with a leather case that fits around the wooden cabinet, and which is still intact - a rarity! Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet sale site.

Figure 8D.

An Oberhaeuser “Microscope Achromatique à Grossissements Variables” (achromatic microscope with variable magnifications) that was owned by Louis Agassiz. It has serial number 1194, and was manufactured ca. 1845. This model was first produced by Oberhaeuser and Trécourt in 1839. The upper rack-and-pinion adjusts the length of the body tube, which changes the apparent magnification of the specimen. The designers promoted this feature as a means to vary the magnification without changing the microscope's lenses. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from http://waywiser.fas.harvard.edu/objects/16205/drum-compound-microscope?ctx=9dd0f741-2899-4a0a-8e05-5577c98391ff&idx=6. Another example of this model, with serial number 790, can be seen at http://www.museum-optischer-instrumente.de/oberhaeuser_790.html.

Figure 8E.

Three sizes of early-/mid-1840s Oberhaeuser drum microscopes. Left to right, serial numbers 1821, 733, and 1249 (see Figures 13A, 8A and 11).

Figure 9.

Two small Oberhaeuser microscopes: left, serial number 638, manufactured ca. 1840; right; serial number 1555, manufactured ca. 1848. This model is essentially the same as that made by Trécourt and Oberhaeuser during the mid-1830s (see Figure 4). Adapted by permission of Timo Mappes, http://www.museum-optischer-instrumente.de/oberhaeuser_638.html and http://www.museum-optischer-instrumente.de/oberhaeuser_1555.html.

Figure 10.

Oberhaeuser’s small microscope was also available in a form that attaches to a boss on the top of the case. This is sturdier than the free-standing version, although it complicates access to the case’s interior. The illustrated example has serial number 2548, and was manufactured ca. 1855. Adapted by permission of Timo Mappes, http://www.museum-optischer-instrumente.de/oberhaeuser2548.html.

Figure 11.

Another form of a small Oberhaeuser drum microscope, with a more robust connection between the bottom and top of the drum. This example has serial number 1249, and was manufactured ca. 1846.

Figure 12.

Original paperwork that accompanied Oberhaeuser microscope 1249 (see Figure 11). The upper half of the left image was machine-printed. The handwritten notes on the magnifying powers of ocular/objective lens combinations were written by Oberhaeuser.

Figure 13A.

Oberhaeuser large drum microscope, serial number 1821, manufactured ca. 1850. It is essentially the same as the microscopes shown in Figures 8A and 8B, but is engraved with only "Georges Oberhaeuser" on one side, and his address, "Place Dauphine, 19, Paris" on the other. The absence of further description is striking - perhaps indicating that the features of Oberhaeuser's microscopes were well-known by this time?

Figure 13B.

Another large Oberhaeuser drum microscope, serial number 2785, made ca. 1855. Adapted with permission of Timo Mappes, http://www.museum-optischer-instrumente.de/oberhaeuser_2785.html.

Figure 14.

An Oberhaeuser medium-sized drum microscope, serial number 1336, manufactured ca. 1846. As with his largest drum microscopes, this model has a revolving upper body (right image). Adapted with permission of Timo Mappes, http://www.museum-optischer-instrumente.de/oberhaeuser_1336.html.

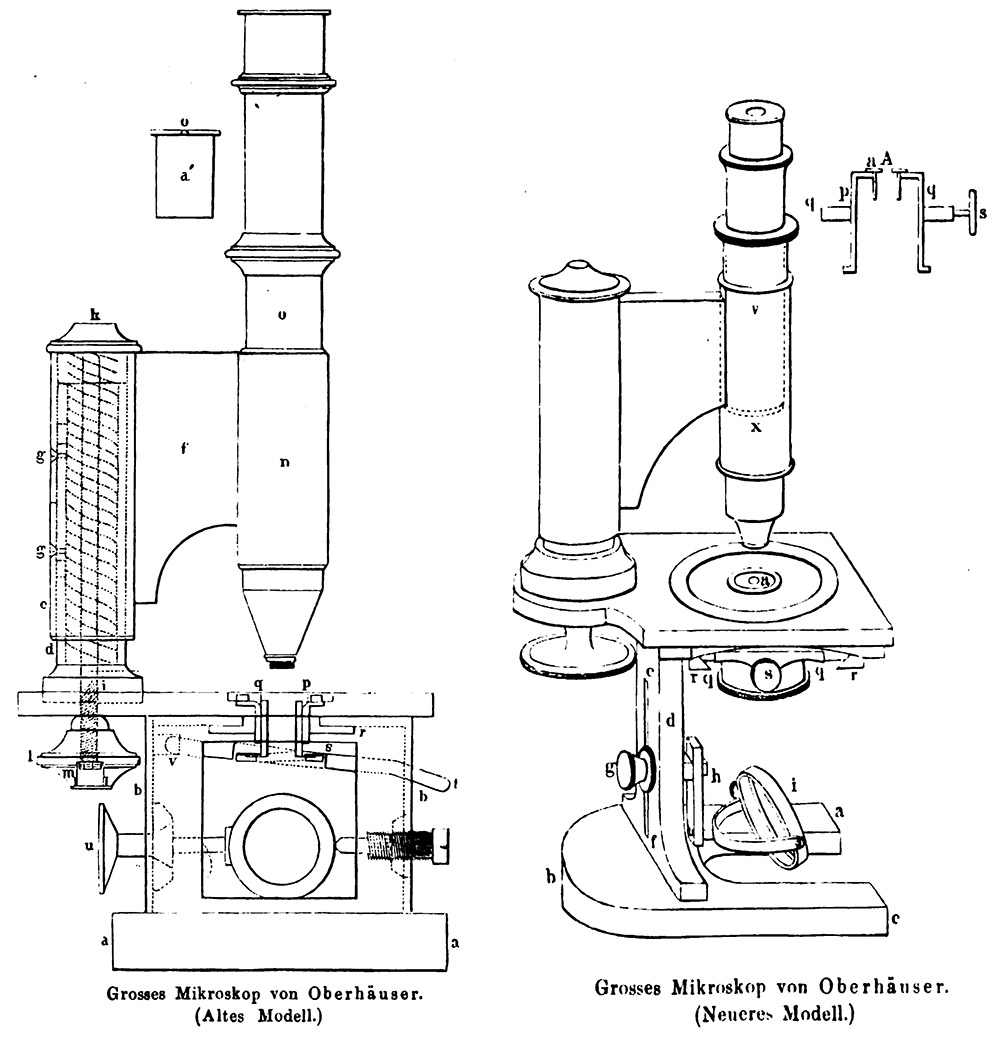

Figure 15.

In 1847, Oberhaeuser began producing microscopes with open bases, which allowed the mirror to be used in a variety of angles to provide oblique lighting. Mounted on a “U” or “horseshoe”-shaped base, this was the first use of the “Continental” foot. These illustrations are from Pieter Harting’s 1866 edition of “Das Mikroskop”.

Figure 16.

An example of the first microscope design that used a “Continental” foot. The inscription “bté” (brevet, i.e. patent) indicates production after Oberhaeuser received his patent for this instrument in 1849. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Figure 16B.

Another "Continental" microscope, signed "Georges Oberhaeuser" and "Place Dauphine 19, Paris". It does not note Oberhaeuser's 1849 patent, and so may have been produced before that date. The knurled knob on the body tube is a post-production modification; the eyepiece and objective lens are original, so it is possible that Oberhaeuser made the modification.

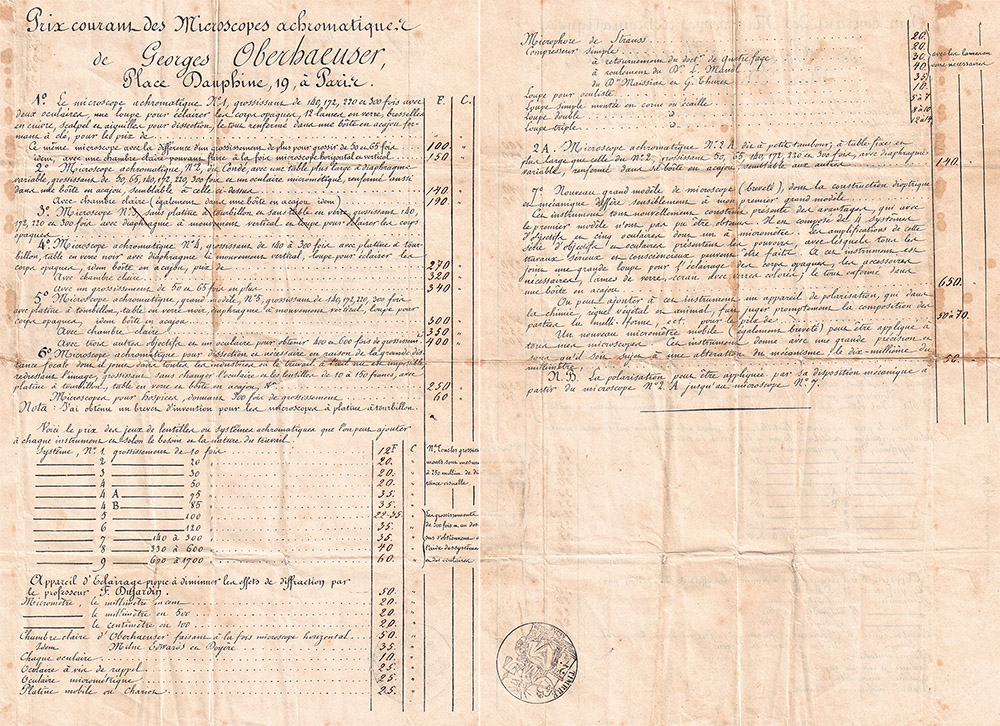

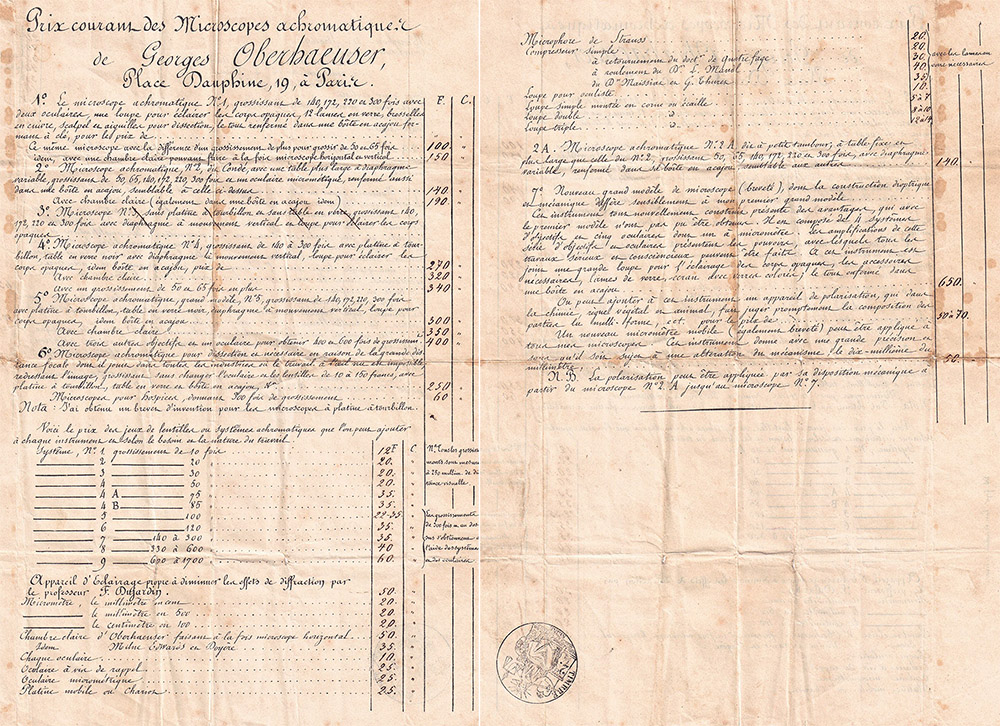

Figure 16C.

Circa 1850 handwritten description of Oberhaueser's microscopes, with prices. The second page describes a "neauveau grand modele de microscope (brevete)", which probably refers to his innovative horseshoe-footed microscope (Figure 16). Adapted with permission from Jurriaan de Groot.

Figure 17A.

A case-mounted small drum microscope by Oberhaeuser and Hartnack. Serial number 3080, manufactured ca. 1856.

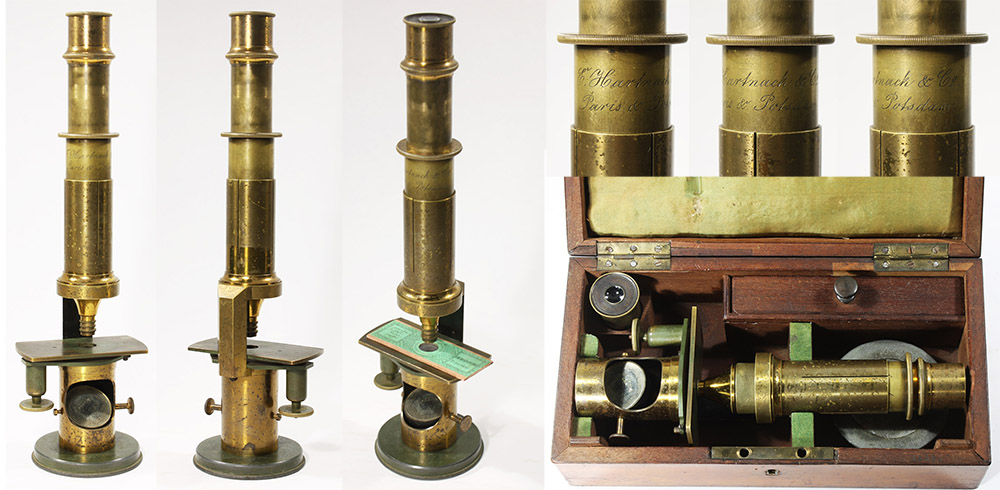

Figure 17B.

"Microscope Achromatique Reduit" by Oberhaeuser and Hartnack, with serial number 3230. The case, the base of the microscope, and the manufacturer's paperwork (see Figure 17C) are all marked with the serial number. Manufactured ca. 1857.

Figure 17C.

The original paperwork that accompanied Oberhaeuser and Hartnack's "Microscope Achromatique Reduit" number 3230 (Figure 17B).

Figure 18.

An Oberhaeuser and Hartnack medium-sized drum microscope, with serial number 3134. Manufactured ca. 1857. Another example of this model may be seen at http://www.museum-optischer-instrumente.de/oberhaeuser_3207.html.

Figure 19.

Signed “E. Hartnack sucr. de G. Oberhaeuser”, this drum microscope is essentially identical to the Oberhaeuser and Hartnack instrument shown in Figure 18. This microscope bears serial number 5024, and was probably manufactured ca. 1865. Adapted with permission of Allan Wissner from http://www.antique-microscopes.com/photos/Hartnack_microscope_5024.htm.

Figure 20.

Edmund Hartnack introduced continental-footed microscopes whose upper bodies were essentially the same as the company’s medium-sized drum microscope (see Figures 18 and 19, above). This example is a Stand IX (later renamed the Stand VIII; see Figure 24), with serial number 3879, is signed “E. Hartnack sucr de G. Oberhaeuser, Place Dauphine 21, Paris”, and was manufactured ca. 1859-60. Adapted by permission of Timo Mappes from http://www.museum-optischer-instrumente.de/Hartnack_3879.html.

Figure 21.

A small, case-mounted drum microscope, signed “E. Hartnack sucr de G. Oberhaeuser, Place Dauphine 21, Paris”. The serial number is not known, but the signature indicates production after 1859. It is essentially identical to the ca. 1856 Oberhaeuser and Hartnack microscope that is shown in Figure 17. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Figure 22.

A large, continental-footed microscope, signed “E. Hartnack sucr de G. Oberhaeuser”. Serial number 4815, made ca. 1864. It is essentially the same as the first Oberhaeuser continental-footed microscopes (see Figure 16, above). Adapted by permission of Timo Mappes from http://www.museum-optischer-instrumente.de/Hartnack_4815.html.

Figure 23.

An unusual microscope with two support columns, signed “E. Hartnack sucr de G. Oberhaeuser”. I am not aware of another such microscope with Hartnack’s signature. Similar instruments appear to have been made by several different sources (an essay on this form can be read here). Hartnack may have produced this model in limited quantities, or perhaps brought it in from another manufacturer for a particular customer. The serial number not known, but the signature dates it to between 1859 and 1870. Adapted by permission from https://www.microscope-antiques.com/doublepillar.html.

Figure 24.

A Stand II microscope, signed “E. Hartnack, Place Dauphine 21, Paris”. A relatively simple instrument, with a wheel of stops built into the stage. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Figure 25.

A Stand VII (formerly Stand IX; see Figure 20), signed “E. Hartnack, Place Dauphine 21, Paris”, with serial number 7398, made ca. 1868. A variant, the Stand VIII-A, has a joint below the stage to allow the upper body to recline, and has a stabilizing extension reaching backward from the foot. The Stands VIII and VIII-A have a complex substage, while the nearly-identical Stands III and III-A have a simple wheel of stops within the stage (see Figures 25, 26, and 28). Adapted by permission of Timo Mappes from http://www.museum-optischer-instrumente.de/Hartnack7398.html.

Figure 26.

A Stand III-A, with simple substage and an extension from the rear for increased stability when the instrument is inclined. It is signed “E. Hartnack, Place Dauphine 21, Paris”. With serial number 11186, it was made ca. 1869. Adapted by permission of Timo Mappes from http://www.museum-optischer-instrumente.de/Hartnack_11186.html.

Figure 27A.

Another Stand III-A, signed “Hartnack et Cie, Place Dauphine 21, Paris”. Manufactured in Paris ca. 1870. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Figure 27B.

An unusual nickel-plated Stand III-A microscope, signed “Hartnack et Cie, Place Dauphine 21, Paris”, indicating production ca. 1870. The cabinet is stamped with serial number 7690.

Figure 27C.

A small drum microscope, signed “Hartnack & Co, Paris & Potsdam”. This instrument was aquired from Ukraine, and so was probably manufactured in Potsdam. The case bears the serial number 15552, which is after some instruments signed "Hartnack & Prażmowski, Paris" (see Figure 28, below). This suggests that Prażmowski was not an equal partner in the Potsdam branch.

Figure 28.

A Stand VII microscope with serial number 12498, inscribed “E. Hartnack & A. Prażmowski, Rue Bonaparte 1, Paris”. Produced between 1873 and 1879. Adapted by permission of Timo Mappes from http://www.museum-optischer-instrumente.de/Hartnack_12498.html.

Figure 29.

A Stand III-A microscope, with serial number 16607, inscribed “E. Hartnack & A. Prażmowski, Rue Bonaparte 1, Paris”. Manufactured between 1873 and 1879. The stage is also engraved “Bryson, Edinburgh”, who was a major importer of these instruments to Scotland.

Figure 30.

A Stand VIII microscope, with serial number 23339, inscribed “E. Hartnack & A. Prażmowski, A. Prażmowski Sucr, Paris”. The signature dates the production of this instrument to after 1878, when Adam Prażmowski acquired full ownership of the Paris business.

Figure 31.

A Stand VIII microscope, with serial number 21097, inscribed “Dr. E. Hartnack, Potsdam”. The serial number suggests production during the late 1870s. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Figure 32.

An example of a Stand VIII-A microscope; note the substage, joint for inclination, and stabilizing extension on the foot. It has serial number 21579, and is signed “Dr. E. Hartnack, Potsdam”. Adapted by permission of Timo Mappes from https://www.musoptin.com/item/labormikroskop-dr-e-hartnack-21579-1880.

Figure 33.

Hartnack’s “Embryograph”, introduced in 1881, is an open-framed, low-power camera lucida. Images of a surviving instrument adapted by permission of Allan Wissner from http://www.antique-microscopes.com/photos/Embryograph.htm. The engraving was published in “The Journal of the Royal Microscopical Society” in 1882 and 1899.

Figure 34.

Circa 1885 Stand V microscope by Hartnack, serial number 24312. Adapted by permission of Timo Mappes from https://www.musoptin.com/item/labormikroskop-dr-e-hartnack-24312-um-1885.

Figure 35.

A different form of Hartnack’s Stand V microscope, serial number 24560, ca. 1885. The foot is different from that of the Stand V shown in Figure 34. Adapted by permission of Timo Mappes from https://www.musoptin.com/item/bakterienmikroskop-e-hartnack-24560-um-1885.

Figure 36.

A ca. 1890 Stand IV-A microscope that is inscribed “E. Hartnack, Potsdam”. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Figure 37.

Circa 1910 small Hartnack’s microscope, serial number 24560, ca. 1885. Adapted by permission of Timo Mappes from https://www.musoptin.com/item/kleines-mikroskop-e-hartnack-um-1900.

A large portion of what follows is drawn from the biography of Oberhaeuser that was written by Lorenz Strebel, the Ansbach schoolmaster. He personally knew Oberhaeuser and his family. Strebel’s essay is full of detailed anecdotes, names, and dates, and was evidently drawn from personal conversations and letters. His information is supplemented with data from official records.

Georg Johann Oberhäuser was born on July 16, 1798, in Ansbach, Bavaria. He was one of three children, having two sisters.

His father, Michael Oberhäuser, was a master wood-turner (lathe operator). Much earlier, Michael had worked in Paris, and was fluent in French. At the outbreak of the 1789 French Revolution, the Marquis de Ponnat and his family fled that country, and settled in Ansbach in a house owned by Oberhäuser. The Marquis’ two sons had previously turned wood as a hobby, and so took up that profession in Bavaria. The Marquis and his wife died around the turn of the century, but the two sons returned to Paris in 1802.

After completing his schooling in 1811, Georg was sent to Würzburg to learn technical engineering and scientific instrument construction with Laurent Dantan du Monceau, another refugee of the French Revolution.

In 1816, Oberhaeuser left Würzburg for Paris. His father’s former tenant and work colleague, the new Marquis of Ponnat, helped Oberhaeuser to settle in and find work. Initially, he worked for Henri Gambey (1787-1847). Within a few years, he moved to work with an optican surnamed Rochette. This would have been one either of the father and son opticians, known as Rochette Père and Rochette Jeune, respectively, who each operated a shop on Quai de l’Horloge. Rochette Jeune is particularly notable as having owned a celebrated shop known as “Au Griffon”, the history of which is described elsewhere on this site”“. In addition to receiving better pay from Rochette than from Gambey, Oberhaeuser learned details of manufacturing high-quality mathematical and optical instruments.

By 1830, Oberhaeuser had grown tired of the work environment at Rochette’s shop. He also felt that he could do as well by working for himself, and so struck out alone. He soon found out that skill alone is not enough: he lacked a reputation, and found it difficult to acquire metals and other supplies on credit.

Those hard times may have been the reason for his (apparently brief) partnership with an optician named Bouquet. A small number of microscopes are known that are engraved “Bouquet et Georges Oberhaeuser” (Figure 2). The inclusion of Oberhaeuser’s first name, but not that of Bouquet, seems to indicate that this was a collaboration of two individual businesses, and not necessarily a full-on parternship. Little is known of Bouquet, including his first name. In 1835, Bouquet provided the French Academy with a pair of optical lenses made from diamonds. Shortly afterwards, Oberhaeuser and his new partner, Achille Trécourt, presented further jewel lenses, and they were described as being competitors of Bouquet. Other dated records imply that Oberhaeuser and Trécourt had established a working relationship by 1833, suggesting that the Oberhaeuser-Bouquet collaboration took place during a time between 1830 and 1833. Bouquet was likely the “opticien” of that name who was listed in a 1837 Paris business directory as having a shop on Quai Napoléon. Of note, microscope slide-maker Joseph Bourgogne worked from that same address, at the same time as Bouquet.

Oberhaeuser’s contempararies credit him with popularizing the the vertical “drum” style of microscope. Based on earlier designs of Benjamin Martin, Oberhaeuser’s drum designs were inexpensive yet sturdy, and became highly popular and widely imitated. His earliest identified microscopes, produced in collaboration with Bouquet, were drum styles (Figure 2). It is possible that a desire to build this revolutionary design spurred Oberhaeuser’s departure from Rochette.

Oberhaeuser clearly worked alone to a large extent, while continuing to advance scientific instrument manufacturing. For example, the January, 1832 issue of Bulletin de la Société d'Encouragement pour l'Industrie Nationale described “la machine à limer les surfaces planes et courbes, inventée par M. George Oberhaeuser, ingénieur en instrumens de précision, place Dauphine, no. 19” (“a machine to file flat or curved surfaces”). A translated description: “The tool that works the metal is a simple chisel that receives from the machine a quick movement back and forth, so that it removes only one chip each time it is brought back; at the same time, the piece to be filed receives from the hand of the workman a very slow movement of translation which is directed perpendicular to that of the chisel, the result being that the furrows produced by this tool are perfectly contiguous and parallel, the surface is worked in the most regular manner, without showing any solution of continuity between the furrows; only, looking at it in a certain light, one sees iridescent reflections which are a play of light attesting the regularity of the mode of action employed. With this machine, in a given time, we obtain the same work as five workers, and the product is much better executed. However, its use is limited to metal parts, mainly brass and copper, which are used in the construction of astronomy, geodesy and navigation instruments”. This report indicates that Oberhaeuser was working alone, under his own name, in late 1831 and early 1832. It also shows that he was already established at 19 Place Dauphine at that time.

One day, prior to 1833, Oberhaeuser had a chance encounter with Achile Trécourt in a coffee shop. Trécourt was a clerk in the Ministry of War and, upon learning of Oberhaeuser’s skills, invited him to take a position with the Ministry to repair mechanical equipment. The quality of his work, and promptness of delivery, soon led to orders for new apparatus from the Ministries of both War and Navy. Among these orders, Oberhaeuser manufactured surveying equipment of his own design for the Ministry of War between 1833 and 1836 (Figure 3). Notably, his name alone was associated with those devices.

Trécourt played another significant role in Oberhaeuser’s business, that of showing off the latter’s microscopes and introducing him to the top scientists of France and elsewhere. Oberhaeuser’s microscopes were soon widely known for their superior quality, and were in use throughout Europe.

As noted above, Oberhaeuser and Trécourt delivered microscope lenses to the French Academy in 1835. The pair were jointly awarded a patent in 1837, for a large drum-style achromatic microscope, the body of which revolves around the optical axis: “MM. Oberhaeuser (Georges), ingénieur-mécanicien, demeurant place Dauphine, no. 19, et Trécourt (Achille), demeurant rue Saint-Dominique-Saint-Germain, no. 29, à Paris, auxquels il a été délivré, le 17 août dernier, le certificat de leur demande d'un brevet d'invention de cinq ans, pour un microscope achromatique vertical à miroir fixe, avec platine à tourbillon, fonctionnant sans déplacement de l'axe optique, par rapport à l'objet soumis à i'observation”. Examples of this design are shown in Figure 6.

Another new variant of microscope by Trécourt and Oberhaeuser was announced in 1839, their “Microscope Achromatique à Grossissements Variables” (achromatic microscope with variable magnifications) (Figure 7). This large drum-style microscope has a rack-and-pinion that adjusts the length of the body tube, which changes the apparent magnification of the specimen. The makers stated that this feature allowed users to change the magnification without switching microscope lenses.

Oberhaeuser developed a relatively inexpensive type of mechanical stage in about 1839 (Figure 8). It was described that year in Louis Mandl’s Traité Pratique du Microscope. The stage is moved by two screws, positioned 90 degrees from each other, while a spring mechanism holds the stage in position. Of particular interest, Mandl wrote that the mechanical stage was produced by “Georges Oberhaeuser”, without mention of Trécourt, suggesting that the partnership had come apart by the time that Mandl’s book was published.

The nature of the relationship between Oberhaeuser and Trécourt seems to have been complex, and its duration is unclear. Microscopes were engraved with both of their names, and they were listed together in the above-noted 1835 description of jewel microscope lenses and in later descriptions of microscopes. Yet surveying equipment was described as Oberhaeuser’s alone. That may have been due to Oberhaeuser producing surveying apparatus under direct contracts from the French government, whereas microscopes would have been piecemeal work for private individuals. Trécourt arranged important connections for Oberhaeuser; perhaps those opportunities enticed Oberhaeuser to form the partnership. It is also possible that Trécourt provided capital to purchase raw materials, since an inventory would be necessary for display to potential customers, and Oberhaeuser struggled with poverty during his early days of business. The Oberhaeuser-Trécourt partnership appears to have ended circa 1839, when microscopes began to be described with only Oberhaeuser’s name.

It may be significant that the 1840 edition of the Paris Annuaire Général (published in late 1839) marked the first appearance of a listing for “Oberhaeuser, opticien”. Although Oberhaeuser had lived at that address since at least 1832, he had not been listed in the Annuaire Général, which was a directory of businesses.

Oberhaeuser continued to make all of the forms of microscopes that he had made with Trécourt, with continued emphasis on the economical and practical drum style. In a letter from Oberhaeuser to Pieter Harting that was dated February 20, 1848, he wrote, “si j’ai rendu jamais service à la science, c’est d’avoir fait le premier des microscopes à bon marchée, pour que les savants qui ordinairement ne sont pas riches délier leurs bourses plus facilement” (“if I ever rendered a service to science, it was by being the first to make inexpensive microscopes, so that scholars who are not wealthy can readily afford to purchase them”) (my thanks to Jeroen Meeusen for sharing information in that letter).

During 1840, Oberhaeuser provided a valuable service to the French government, while also endangering his safety. All gold and silver goods produced in France were required to be stamped with an official mark, indicative of tax payment. The Ministry of Finance noticed that taxes from gold and silver were declining, even though exports of those goods were increasing. A conspiracy of fraudulent tax stamps was uncovered, and Oberhaeuser gave expert testimony wherein his microscope clearly showed differences between official and counterfeit tax stamps. The criminal syndicate behind the counterfeit stamps made threates against Oberhaeuser, so he decided to leave town for a while.

This gave him an excuse to make a long-overdue trip home to Ansbach, having been away since 1816. Oberhaeuser had left home with only a few coins in his pocket, but he returned in the spring of 1841 as a very wealthy man. His mother and sisters were still alive, and he spent the summer with them, returning to Paris in September of that year.

Oberhaeuser made a cameo appearance in Benjamin Daydon Jackson’s biography of botanist George Bentham (1800-1884). Quoting Bentham’s diary entry of Saturday, June 7, 1845, “After breakfast to the Theatre Francais to take places, and did some commissions; with Scudamore to Baron Delessert's, then home and to the Jardin des Plantes, where found only Ad. Brongniart and Tulasne. To Oberhaeuser, 19 Place Dauphin, for a microscope ordered by Mr. Edgeworth on an excellent plan; found him au deuxiéme (at the moment) in such a nasty house, but surrounded by microscopes, which he finishes up very nicely”. The author, B.D. Jackson (1846-1927), was also a significant botanist and skilled microscopist - an illustrated essay on his life and microscope slide preparations is presented elsewhere on this site.

In 1847, Oberhaeuser introduced another revolutionary development to microscope design: he opened up the base of his drum pattern, so that the mirror could accept light from all angles. The round foot of the drum became an elongated “U” or horseshoe-shape, and Georges Oberhaeuser had invented the “Continental” foot that dominated microscope design into the 1900s. In his 1849 patent, Oberhaeuser wrote, “Les personnes qui travaillent sérieusement avec les microscopes connaissent l'immense importance qu'il y a de pouvoir parfaitement éclairer les diverses parties des objets soumis à l'observation, et en outre le grand avantage de faire varier à volonté la lumière sur divers points de ces objets. L'instrument pour lequel je demande le présent brevet possède ces qualités au degré le plus éminent, avec la propriété de conserver son axe optique dans le mouvement circulaire de la platine, par rapport à l'objet soumis à l'observation, tout en ayant le mérite de pouvoir être commodément manié, ou autrement dit, cette nouvelle combinaison permet d'accomplir, avec toutes les facilités désirables, les différents travaux que l'on peut avoir à effectuer avec les microscopes. Ce nouveau microscope est porté par un pied dont la base est découpée en forme de fer à cheval, afin de dégager le centre de l'instrument, tout en lui donnant la solidité désirable”. (“People who work seriously with microscopes know the great importance of being able to perfectly illuminate the various parts of objects under observation, and, in addition, the great advantage of varying the illumination on various points these objects at will. The instrument for which I am applying for this patent has these qualities to the highest degree, with the property of retaining its optical axis in the circular movement of the stage, with respect to the object under observation, while having the merit of being able to be conveniently handled, or in other words, this new combination makes it possible to accomplish, with all the desirable facilities, the various works that one may have to carry out with microscopes. This new microscope is carried by a stand, the base of which is cut in the shape of a horseshoe, in order to clear the center of the instrument, while giving it the desired stabilty.”).

Pieter Harting wrote about Oberhaeuser and his collaborators, “They have the merit of having seen that if the newer microscopic improvement for science and their disciples really fruitful to be, the mechanical device must be as simple as possible, so that the lower price makes it possible even less well-off naturalists to acquire a useful instrument for most observations. In particular, Georg Oberhäuser, who was born in Anspach, has achieved great merit in this regard. After having separated from the two partners mentioned above, he worked for himself for a number of years, and there is no second workshop from which an equal number of microscopes have emerged. I received from him in 1848 a large microscope, No. 1550, and Professor W. Vrolik received the microscope No. 1786 on March 7, 1850, so that in less than one and a half years 236 microscopes came from this workshop. In 1859 the number of manufactured microscopes rose to more than 3000”. (“Dabei kommt ihnen das Verdienst zu, eingesehen zu haben, dass, wenn die neuere Mikroskopverbesserung für die Wissenschaft und deren Jünger wirklich fruchtbringend sein soll, die mechanische Einrichtung möglichst einfach sein muss, damit der geringere Treis es auch den weniger bemittelten Naturforschern möglich macht, sich ein zu den meisten Beobachtungen brauchbares Instrument anzuschaffen. Namentlich hat sich der in Anspach geborne Georg Oberhäuser in dieser Hinsicht grosse Verdienste erworben. Nachdem er sich von den beiden vorhin genannten Compagnons getrennt hatte, arbeitete er eine Reihe von Jahren hindurch für sich allein, und es giebt keine zweite Werkstatt, aus der eine gleich grosse Anzahl von Mikroskopen hervorgegangen ist. Ich erhielt von ihm im Jahre 1848 ein grosses Mikroskop, Nr. 1550, und Professor W. Vrolik empfing am 7. März 1850 das Mikroskop Nr. 1786, so dass also in noch nicht ganz anderthalb Jahren 236 Mikroskope aus dieser Werkstatt gekommen sind. Im Jahre 1859 erhob sich die Ziffer der gefertigten Mikroskope bereits auf mehr denn 3000”).

Edmund Hartnack joined Georges Oberhaeuser’s workshop in about 1850. Hartnack had been born on April 9, 1826, in Templin, Brandenburg (some 80 kilometers north of Berlin). His father, Karl Ludwig Hartnack, was described in records as having been a “Kaufmann” (merchant) and “Schiedsmann” (arbitrator) of the city of Potsdam. From 1842 until 1847, Edmund Hartnack worked in Berlin as an apprentice to Wilhelm Hirschmann (1780-1847). Moving to Paris in 1847, he found work with Heinrich Rühmkorff (1803-1877), a scientific instrument-maker who is best known for designing electrical devices such as induction coils and lamps.

Oberhaeuser evidently grew to trust and respect Hartnack, and formed the partnership of “Oberhaeuser and Hartnack” in 1854. Strebel’s memorial of Oberhaeuser states that he retired from work upon creating the partnership, suggesting that Oberhaeuser retained a financial interest in the business but left the day-to-day operations to Hartnack. In mid-1855, the business address changed from 19 to 21 Place Dauphine - it is not clear whether this was a change in locations or a renumbering of the street.

On April 24, 1855, Edmund Hartnack married Oberhaeuser’s niece, Johanna Maria Louise Kleinod, in Ansbach. She was a daughter of Georges Oberhaeuser’s sister, Maria.

Oberhaeuser and Hartnack won a Medal First Class at the 1857 Paris International Exposition, for their display of microscopes and lenses. This included a microscopic apparatus in which the specimen and objective lens were enclosed in a vacuum chamber to “faciliter certaines recherches délicates dans lesquelles on doit craindre les illusions produites par des bulles d'air qui sont renfermées dans les liquides” (“facilitate precise studies that may be distorted by air bubbles in liquids”).

Hartnack completely took over the business in 1859, and the name changed to simply “Hartnack” (Figure 40).

A brother of Johanna’s, Johann Kristopher (Jean-Christophe) Kleinod, joined the business, probably around the time of Edmund and Johanna’s marriage. Kleinod left to open his own microscope and scientific instrument shop in about 1863, but died soon afterward, in 1866. Another of Hartnack’s’ employees, Constant Verick (1829-1892) then purchased the Kleinod business. Verick married Kleinod’s widow in 1869, and thus became an indirect relative of Hartnack’s. An illustrated essay of the Kleinod-Verick microscope business is presented elsewhere on this site.

In 1864, Hartnack had the good fortune to hire Adam Prażmowski, an accomplished Polish astronomer who had come to Paris to further his studies, but whose educational visa had expired.

Adam Józef Ignacy Prażmowski was born in Warsaw on March 15, 1821 into a wealthy family. His father, Józef Prażmowski, was a judge, and his uncle, Adam Michał Prażmowski, was bishop of Płock.

In 1839, Adam Prażmowski became an assistant at the Warsaw Astronomical Observatory, under director Franciszek Armiński (1789-1848). Here, Prażmowski learned to calculate and create optical lenses, as well as produce glass items such as barometers and thermometers. He installed a pendulum along the form of Jean Foucault, to demonstrate the rotation of the earth. For additional income, Prażmowski repaired and manufactured scientific instruments.

From 1846 to 1849, Prażmowski was involved with surveying projects throughout Poland and into Prussia and Austria. He returned to the Warsaw Observatory in 1849, taking the position of First Assistant. He continued to make trips around Europe to observe astronomical phenomena, including analyses in Spain of the sun’s corona during the solar eclipse of 1860.

During the summer of 1863, Prażmowski began studies in Paris. To make ends meet, he took a position with Hartnack in 1864. Prażmowski’s experience with making and repairing scientific instruments proved invaluable to his new employer. By 1865, Prażmowski was appointed as Hartnack’s mechanical director. Hartnack and Prażmowski jointly published a scientific paper on polarized light in 1866, in Annalen der Physik.

Georges Oberhaeuser died on January 11, 1868, after “une longue et douloureuse maladie” (“a long and painful illness”).

That summer, Edmund Hartnack was awarded an honorary Doctorate in Medicine from the University of Bonn, for his advances in optics. Thereafter, he was often referred to as “Doctor Hartnack”. Among the other honorees were Louis Pasteur and Charles Darwin. One wonders whether Georges Oberhaeuser would have received such an honor if he had lived?

The Franco-Prussian War broke out on July 19, 1870. Being a Prussian, Hartnack was compelled to leave Paris. He moved to Potsdam, near Berlin, and opened a microscope factory and shop. The Paris branch was probably managed by Prażmowski, and became known as “Hartnack et Cie”. For the next several years, the Paris and Potsdam branches produced essentially identical microscopes.

The 1874 Paris Annuaire-Almanach, which was published in late 1873, included “Hartnack et Prażmowski”, indicating a change in the two men’s relationship from employer-employee to partners. The Annuaire-Almanach also indicated that the shop had moved during 1873 from 21 Rue Dauphine to 1 Rue Bonaparte.

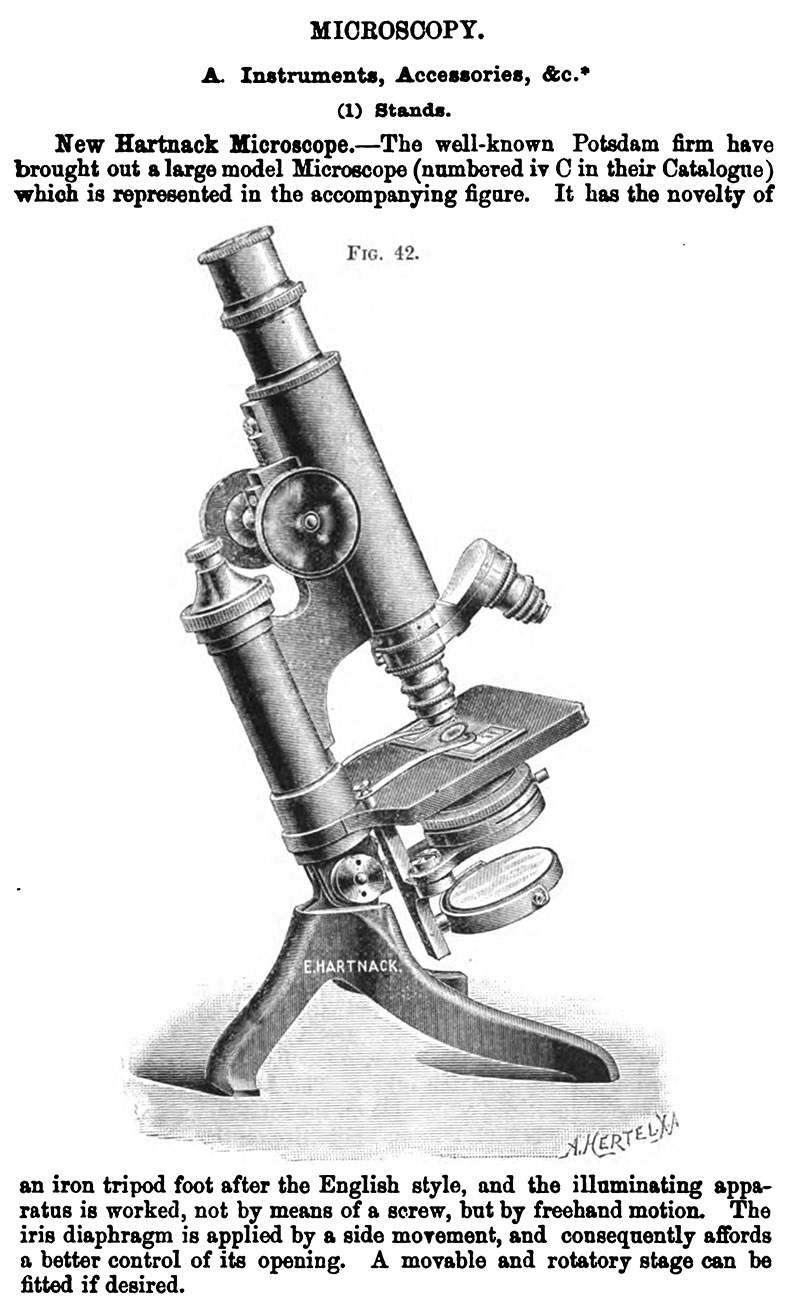

Hartnack and Prażmowski’s horseshoe-footed Stands III and III-A had become very popular by this time, and those models are nowadays the most commonly-encountered of their microscopes. William Rutherford’s 1875 Outlines of Practical Histology stated that “in the histological section of the class of Practical Physiology in the University of Edinburgh, the student is supplied with a Hartnack's No. IIIA microscope, having a No. 3 and a No. 7 objective, and a No. 3 eyepiece” (Figure 42). This instrument was available in England from several dealers. Additionally, James Swift produced a knock-off, “Swift’s improved form of Hartnack’s microscope” (Figure 43).

The Stand III was also preferred by institutions as far away as the McGill School of Medicine, in Montreal, Canada. William Osler wrote in 1876, “The first essential in a course like this is a proper supply of good microscopes, every student must be furnished with one to enable him to follow out the demonstrations with any degree of satisfaction. These have been obtained from Dr. Hartnack of Paris and Potsdam, and are the same as are in use in the chief laboratories of Europe. No microscope maker, British or foreign, has yet, (as far as my experience goes), made up an instrument at all to be compared with compact, Hartnack's students' microscope. It is small and easily carried about, not burdened with stage movements, &c, and so not liable to get out of order. The object glasses are very superior, possessing a clearness of definition, and power of penetration excelled by few, if any, English lenses. Their uniform excellence is remarkable; of the dozens of lenses by this maker that I have examined, I have never met with an inferior one”.

On July 27, 1878, the partnership of Hartnack and Prażmowski was dissolved (Figure 44). The Paris business was continued by Prażmowski alone, under his own name.

An English writer noted in 1881 that, “It is now eleven years since Hartnack was - in common with other Prussians during the Franco German war - compelled to leave France. He immediately settled in Potsdam, and there established an optical factory for microscopical work. M. Prazmowski - who had been for several years working with Hartnack - was admitted into partnership, and took entire charge of the house in Paris. The exhibit of microscopes, &c, at the Paris Exhibition of 1878, was by the firm Hartnack and Prazmowski. Since that date the partnership has been dissolved; the Potsdam house remaining exclusively Hartnack's and the Paris house Prazmowski's. It is well known in Paris that to M. Prazmowski's mathematical attainments have been due the improvements developed by the house during the past fifteen years or more. It is also known that his labours have not been limited exclusively to microscopical work; he has been remarkably successful in devising telescope object-glasses of very short focus, portable binocular telescopes, a practical form of Heliostat for physical researches, especially for micro-photography, and, more recently, has been engaged in the construction of spectroscopic and photographic apparatus for M. Janssen. He is now finishing an achromatic object-glass of 13in. diameter, for which he computed the formula himself”.

Two of Prażmowski’s employees, Bézu and Hauser, acquired the Paris business in 1883. However, they continued to use Prażmowski’s name until his death, two years later. Adam Prażmowski died in Paris on February 5, 1885.

A separate essay on this site discusses the lives and works of Bézu and Hauser. They sold the business to Alfred Nachet in 1896.

Hartnack continued to produce high quality microscopes in Potsdam for many more years. Additionally, he was appointed Professor at the Potsdam solar observatory. Edmund Hartnack died on February 9, 1891, in Potsdam. The business continued under his name until well into the twentieth century. One should remember that microscopes bearing Edmund Hartnack’s name were produced for several decades after his death.

Figure 38.

An equatorial sundial by Laurent Dantan du Monceau, of Würzburg, with whom Georges Oberhäuser served his apprenticeship. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from the Landesmuseum Württemberg, https://bawue.museum-digital.de/index.php?t=objekt&oges=19022

Figure 39.

Cutaway diagram of Trécourt and Oberhaeuser’s patented drum microscope design, from Louis Mandl’s 1839 “Traité Pratique du Microscope”.

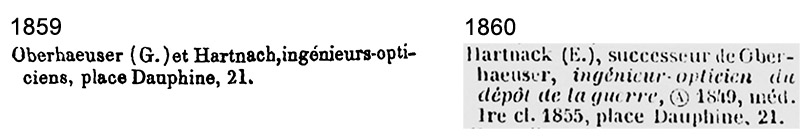

Figure 40.

The firm of “Oberhaeuser & Hartnack” was renamed “Hartnack” during 1859. Excerpts from “Annuaire général”, which was published late in each previous year (the 1859 edition was published in 1858, and the 1860 edition published in 1859).

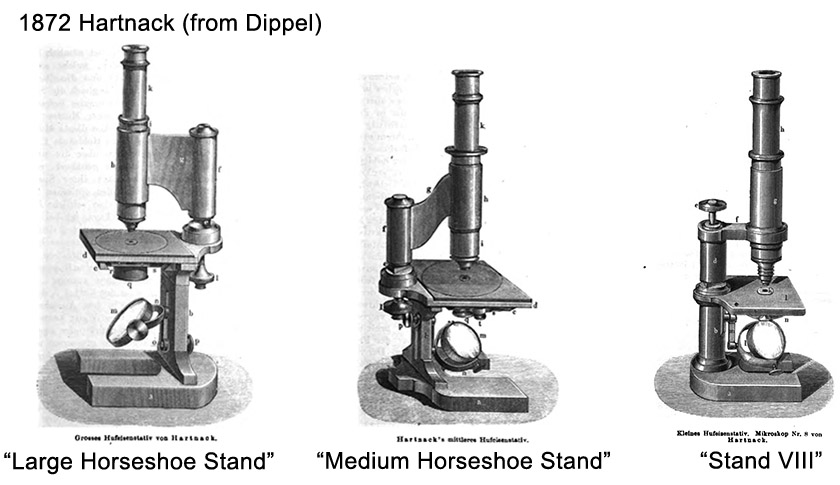

Figure 41.

1872 illustrations of some Hartnack microscope models, from Leopold Dippel’s “Das Mikroskop”.

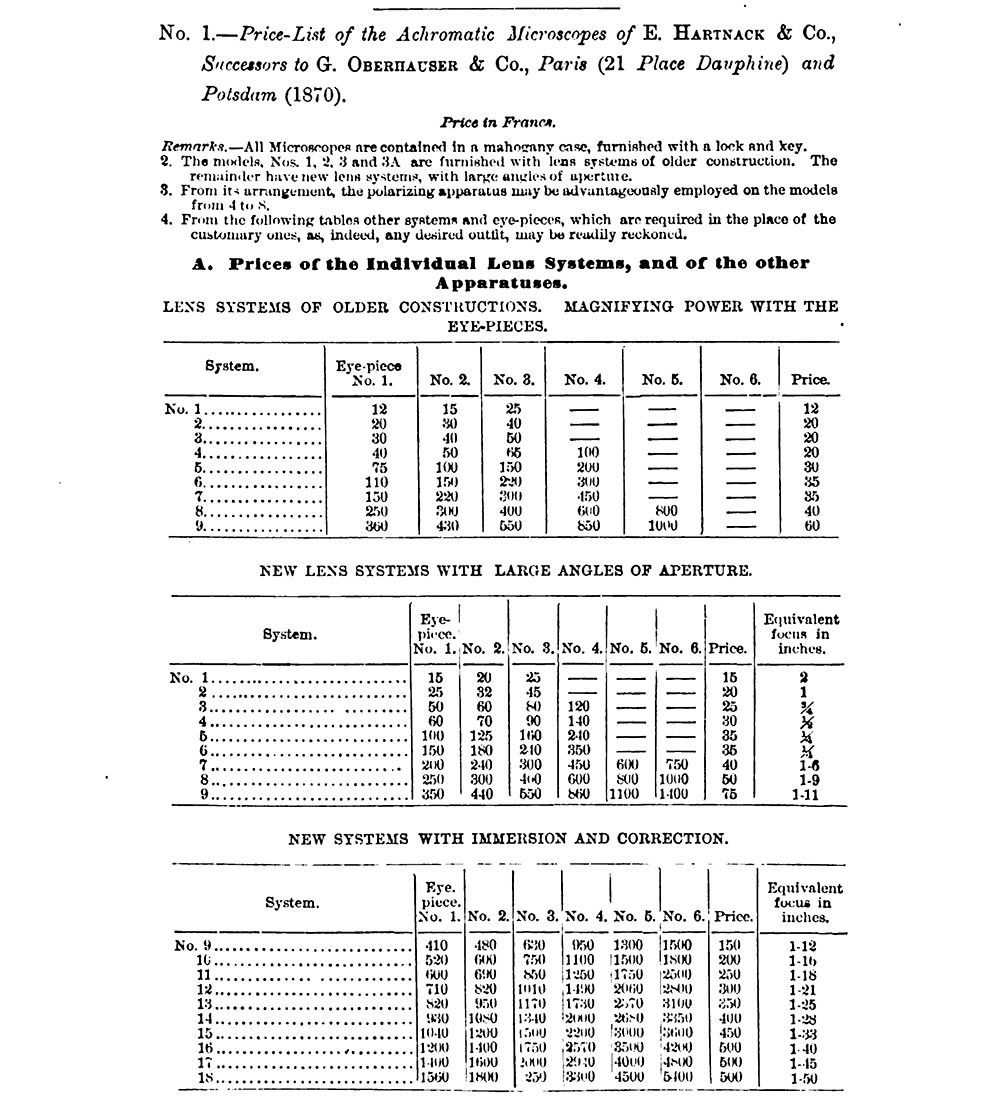

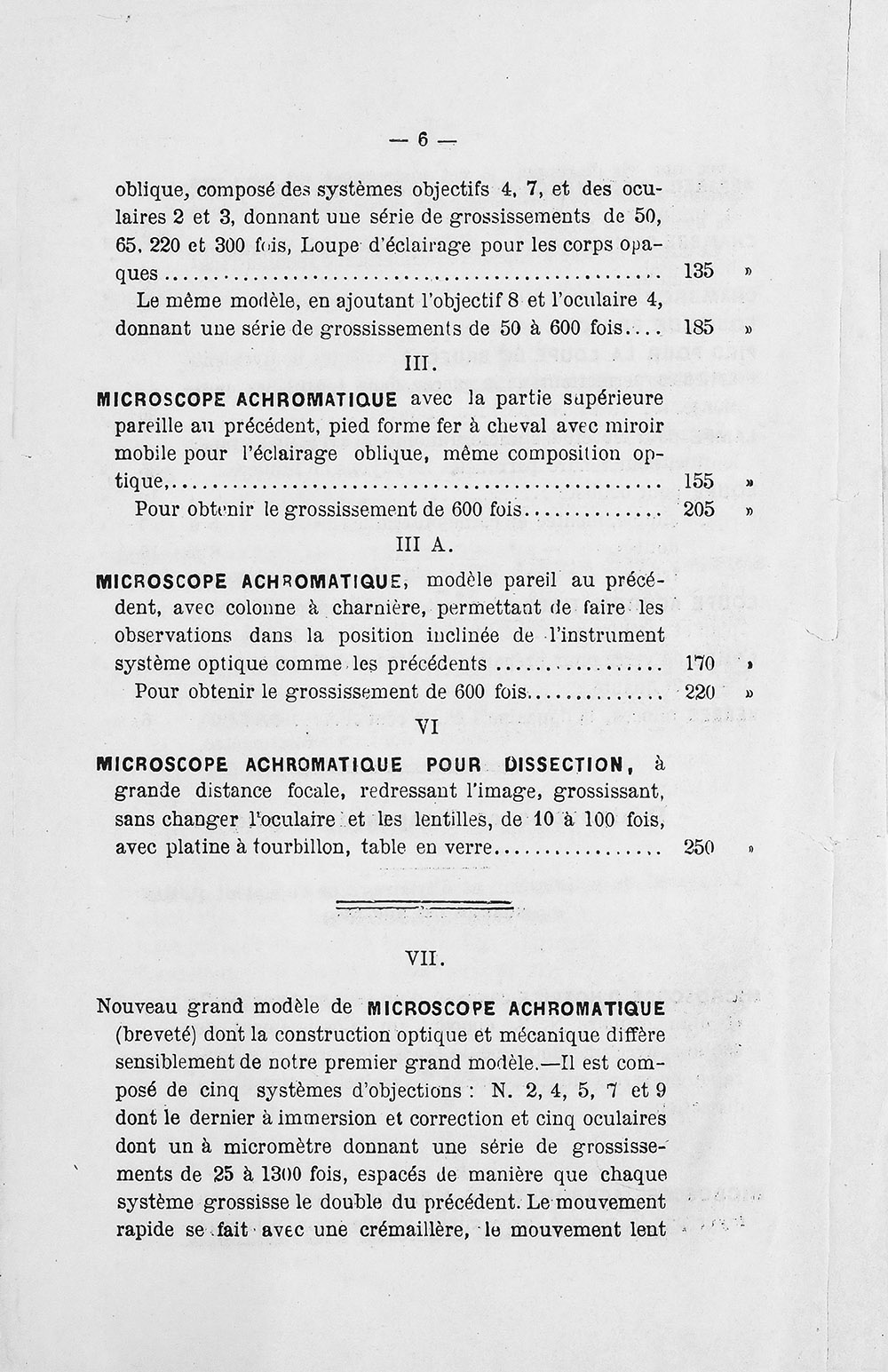

Figure 42A.

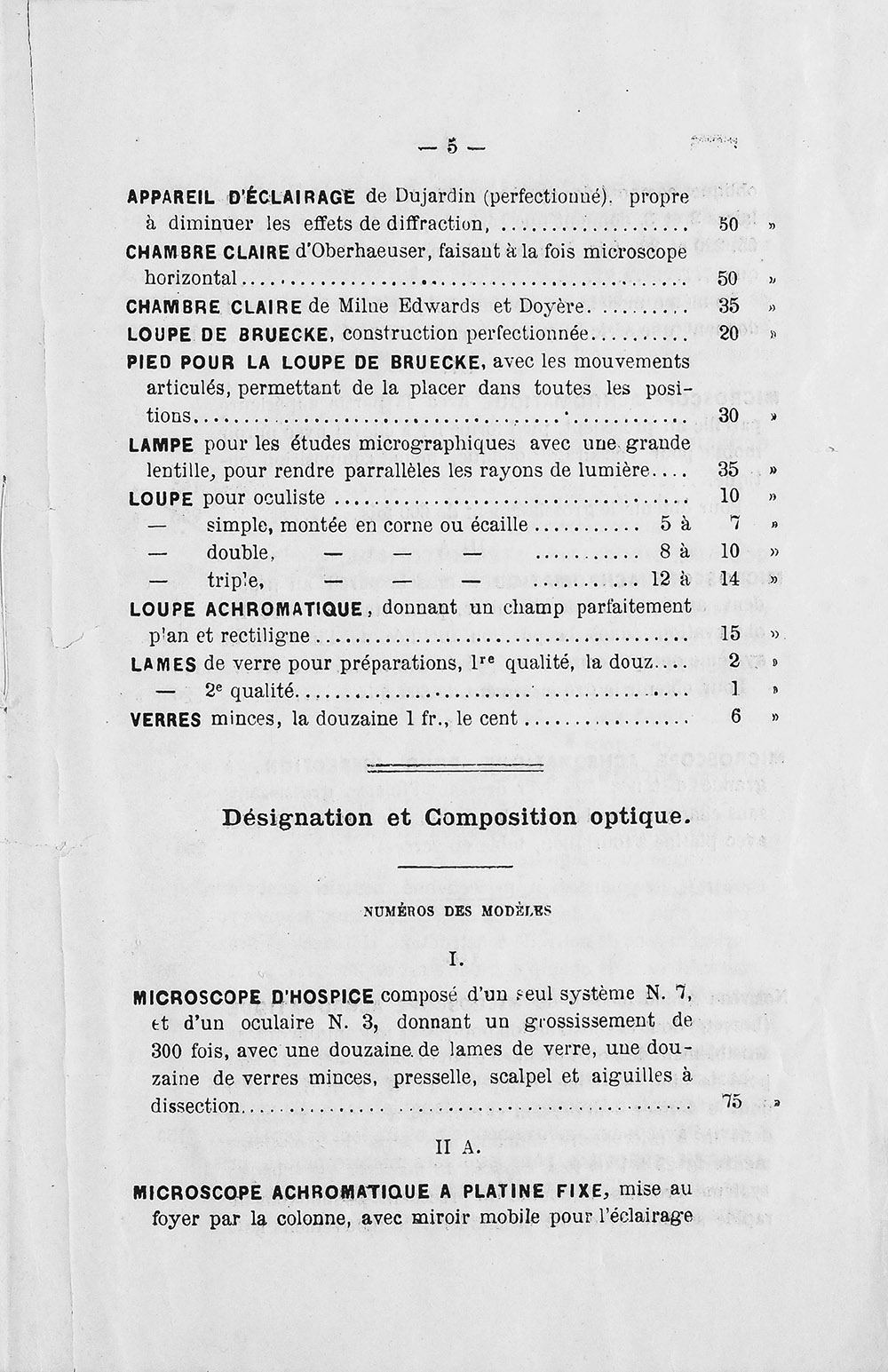

Hartnack and Company’s 1870 catalogue, with prices, from Heinrich Frey's "The Microscope and Microscopical Technology" (English translation, 1872).

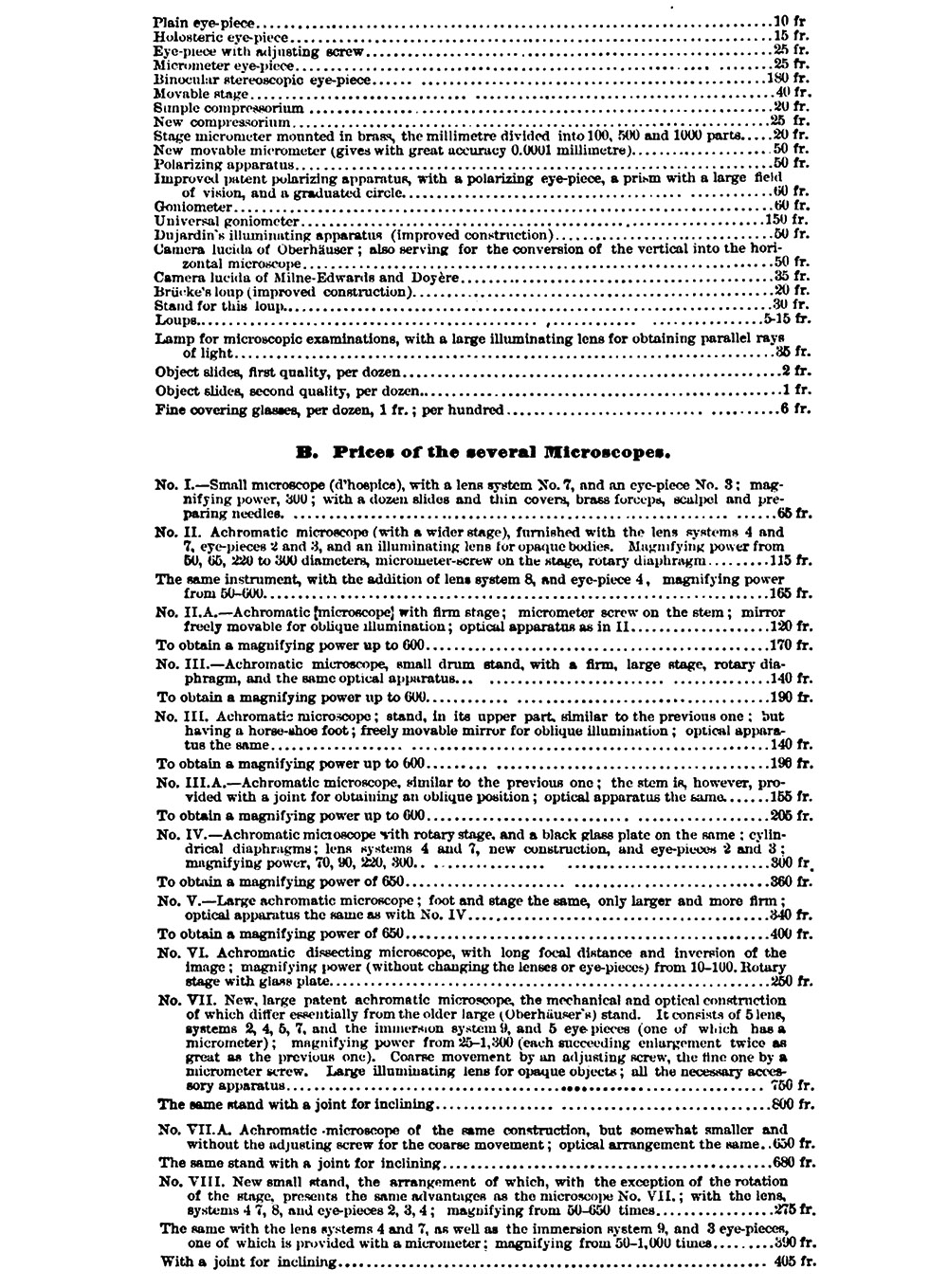

Figure 42A.

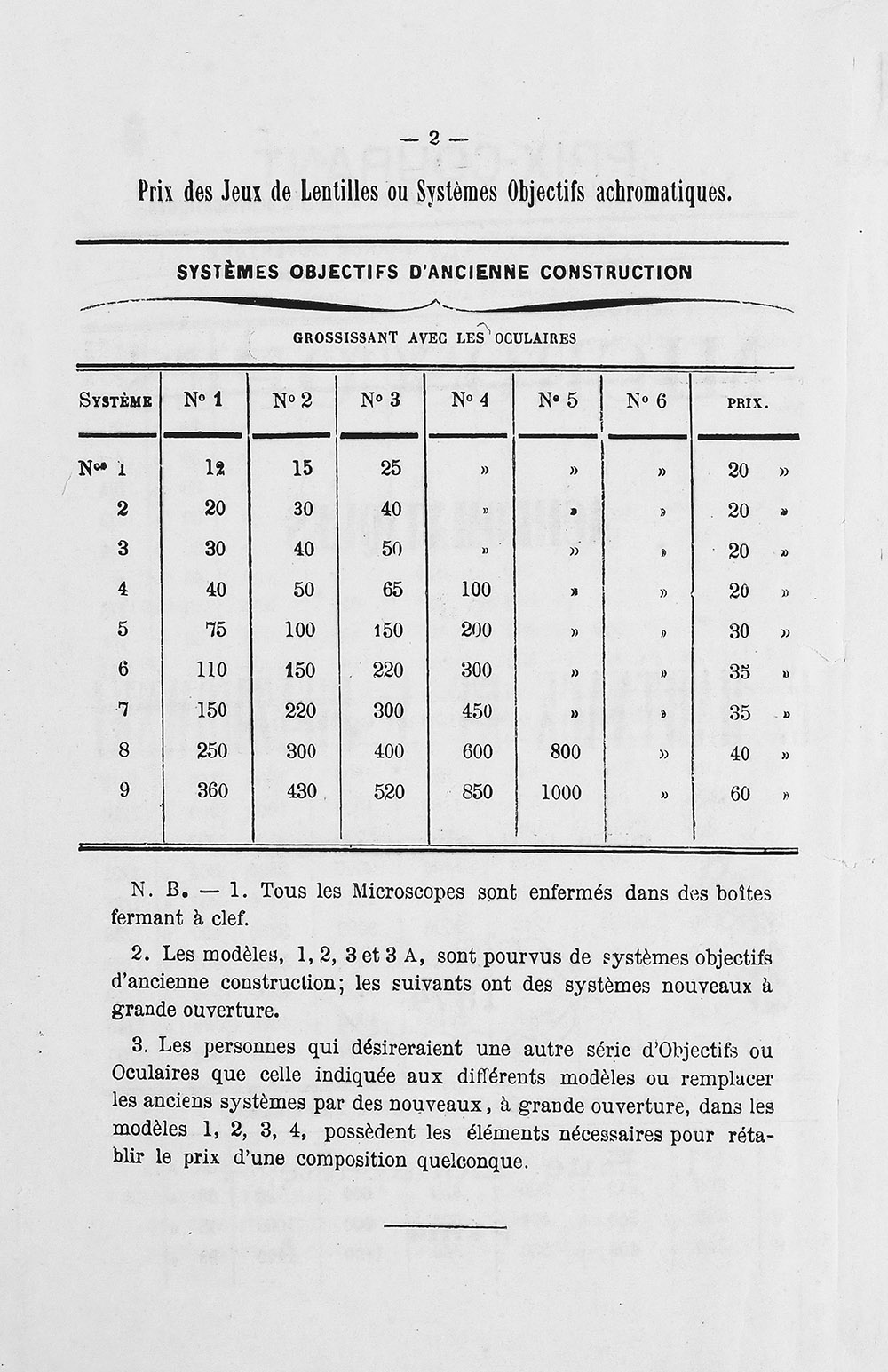

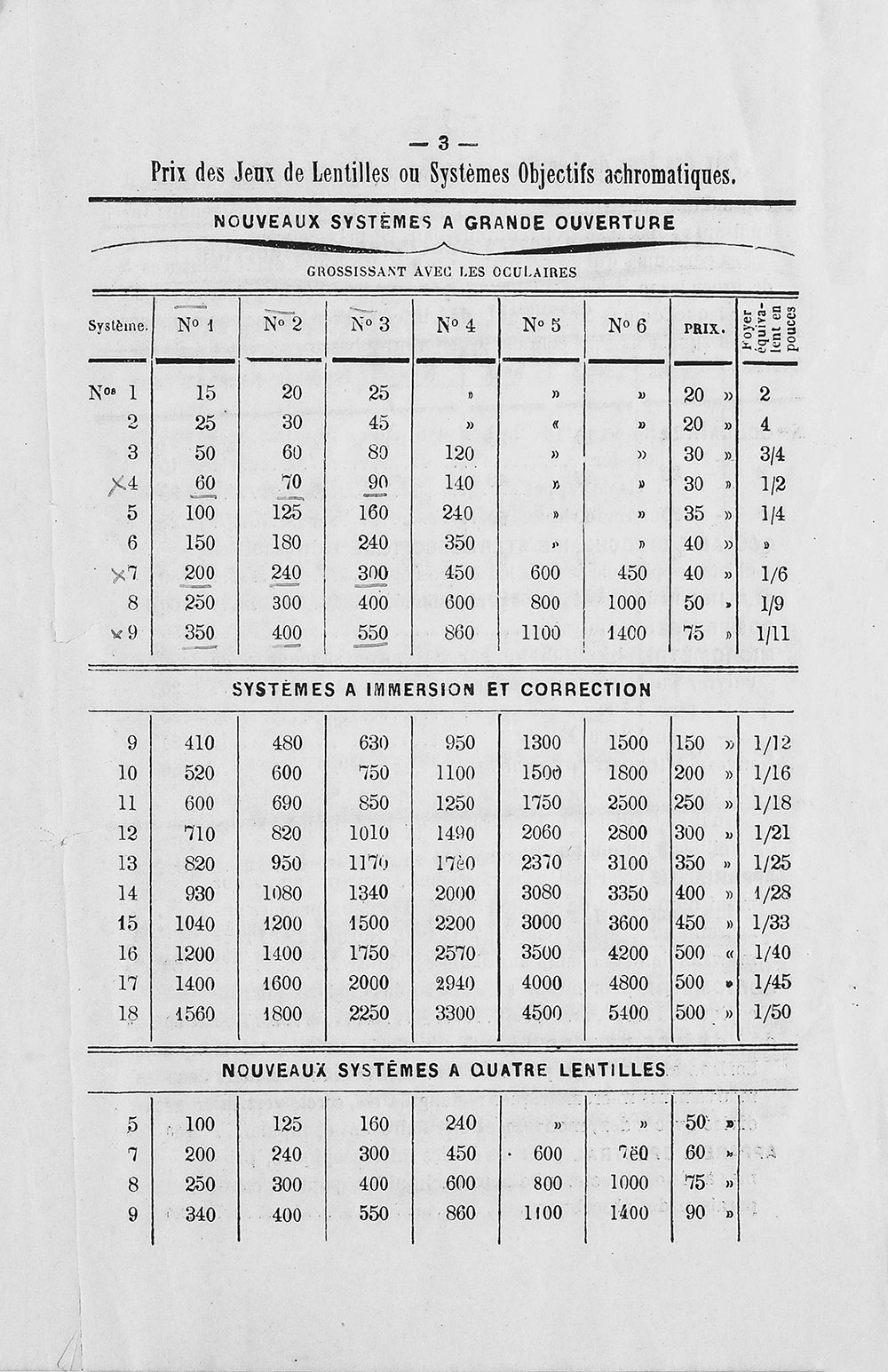

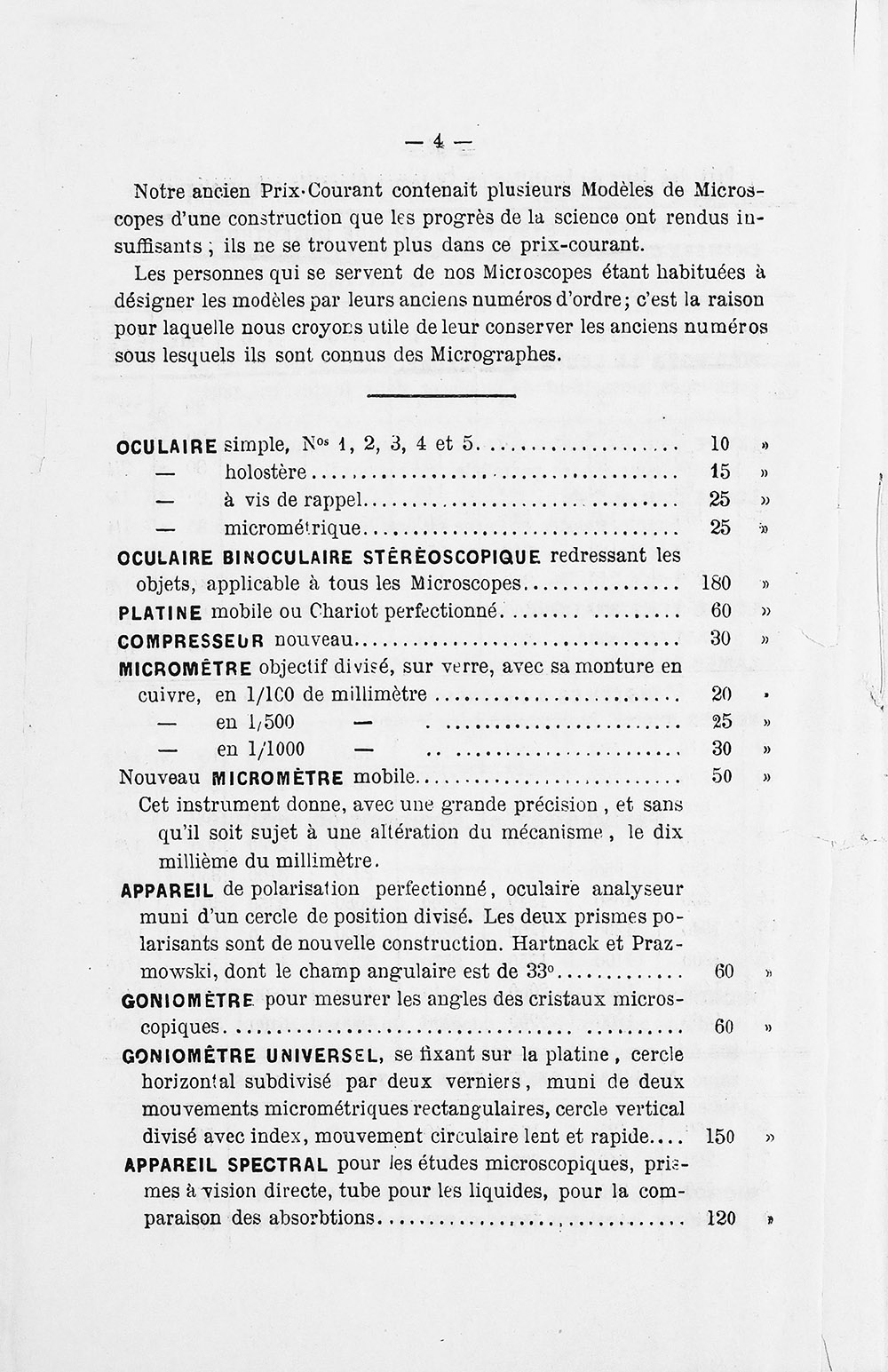

Hartnack and Prażmowski’s 1874 catalogue of lenses and microscope stands, with prices. Reproduced with permission of Andrew VonBank.

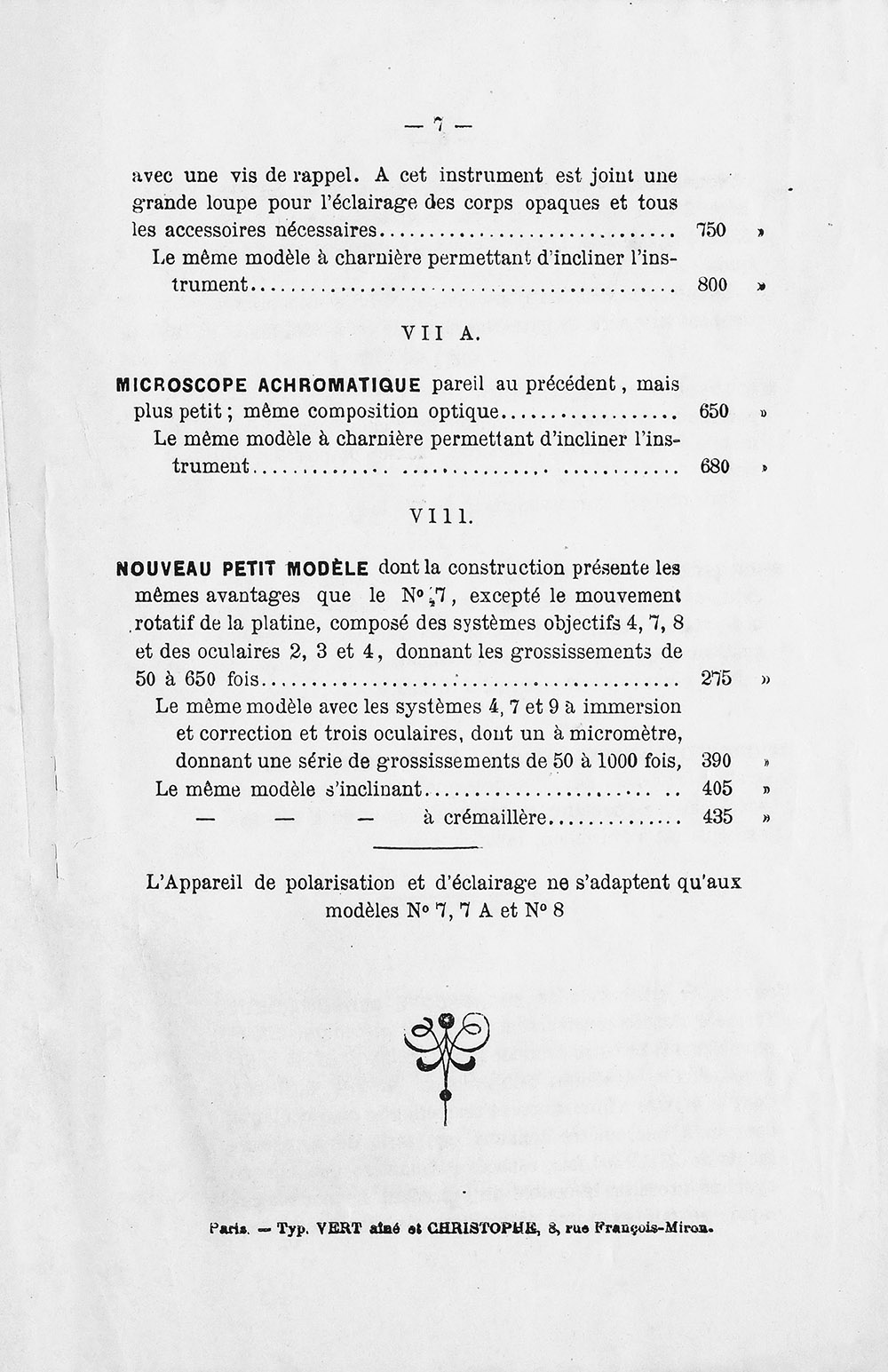

Figure 43A.

An illustration of Hartnack and Prażmowski’s Stand III-A, from William Rutherford’s 1875 “Outlines of Practical Histology”. The author stated, “ In the histological section of the class of Practical Physiology in the University of Edinburgh, the student is supplied with a Hartnack's No. IIIA microscope, having a No. 3 and a No. 7 objective, and a No. 3 eyepiece - the No. 4 eyepiece commonly supplied by Hartnack being intentionally omitted as of little value”, and “Hartnack's microscopes may be obtained from Bryson, Optician, 60 Princes Street, Edinburgh; Tisley and Spiller, 172 Brompton Road, London, SW; Baker, 244 High Holborn, London, WC”.

Figure 43B.

Hartnack and Prażmowski’s popular Stand III-A was copied by James Swift of London, from an 1875 advertisement. Of note, Bryan C. Waller’s 1881 “An Investigation Into the Microscopic Anatomy of Interstitial Nephritis” described “a small and extremely convenient (microscope) by Bryson of Edinburgh, after a design by Swift”!

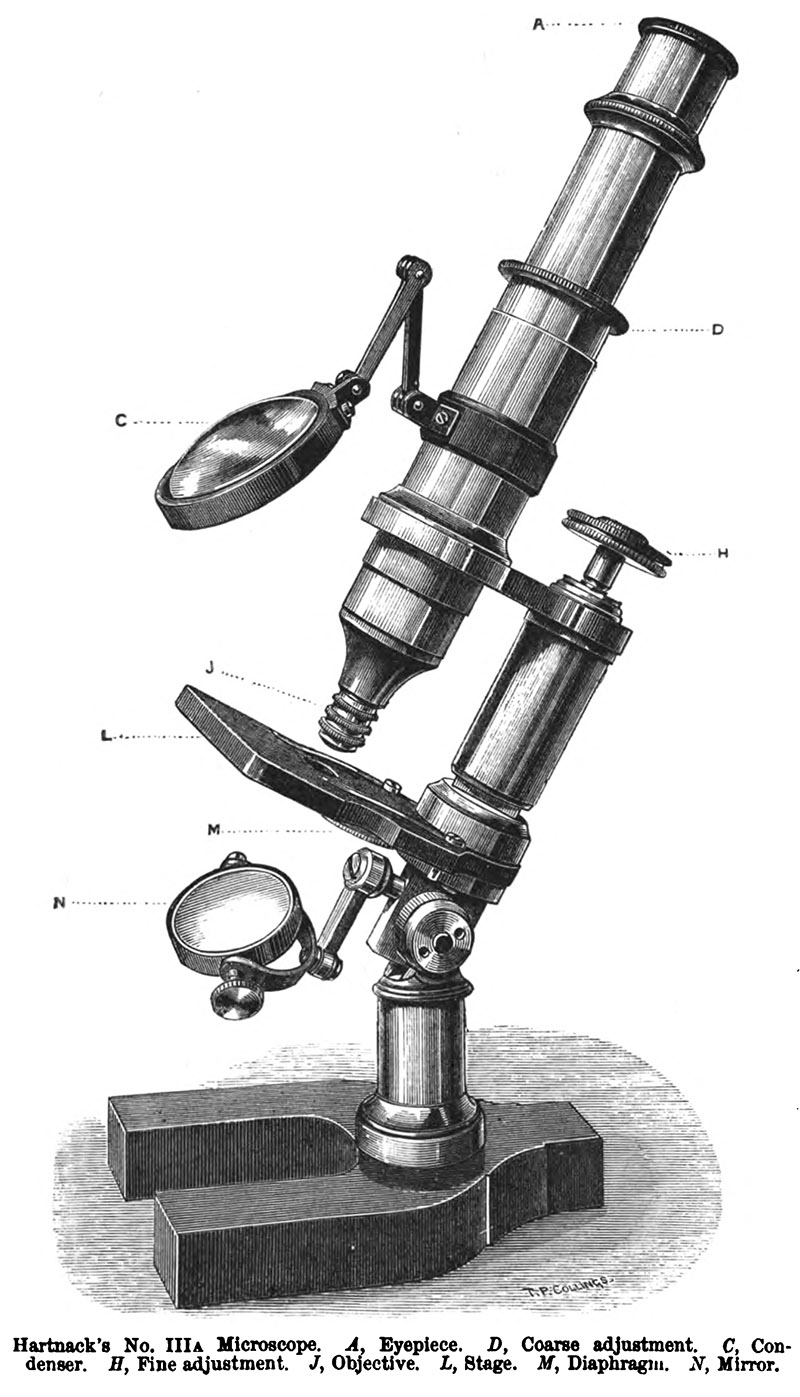

Figure 44.

The partnership between Edmund Hartnack and Adam Prażmowski was dissolved on July 27, 1878. Excerpted from “Archives Commerciales de la France”.

Figure 45.

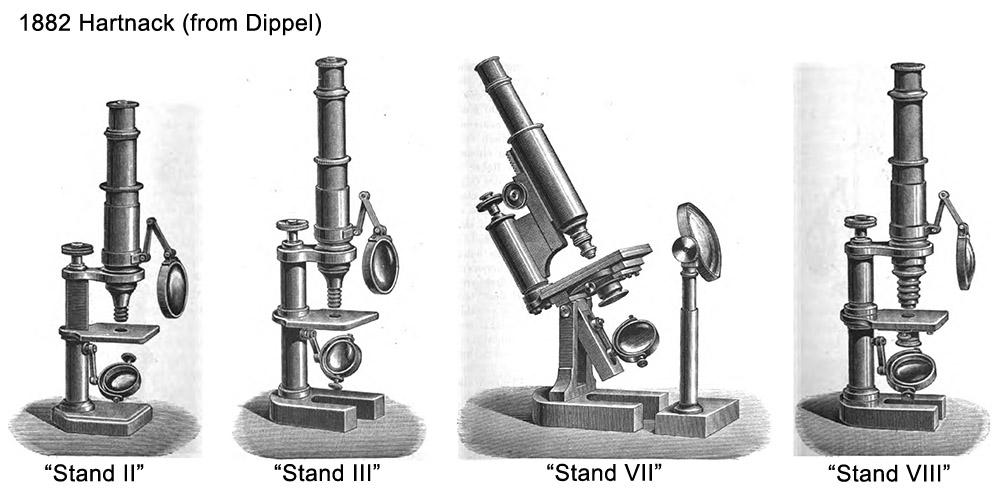

Illustrations of 1882 Hartnack microscopes, from Leopold Dippel’s “Das Mikroskop”.

Figure 46.

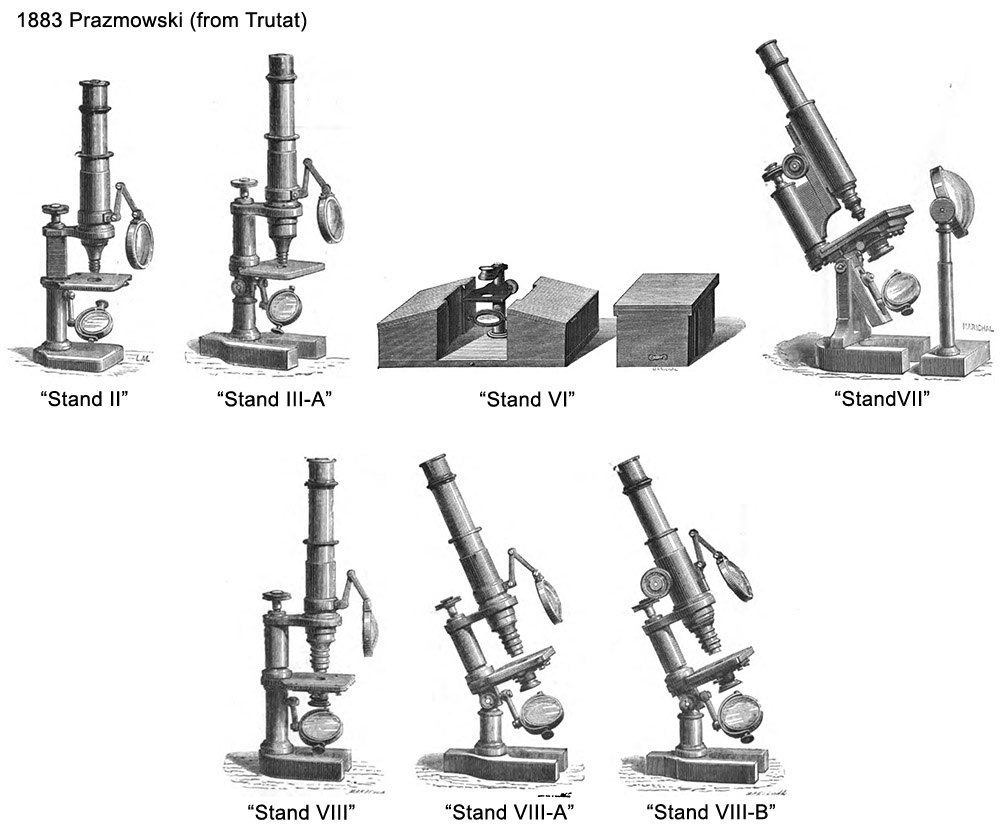

Illustrations of 1883 Prażmowski microscopes, from Eugène Trutat’s “Traité Élémentaire du Microscope”.

Figure 47.

A circa 1880s Prażmowski camera lens. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

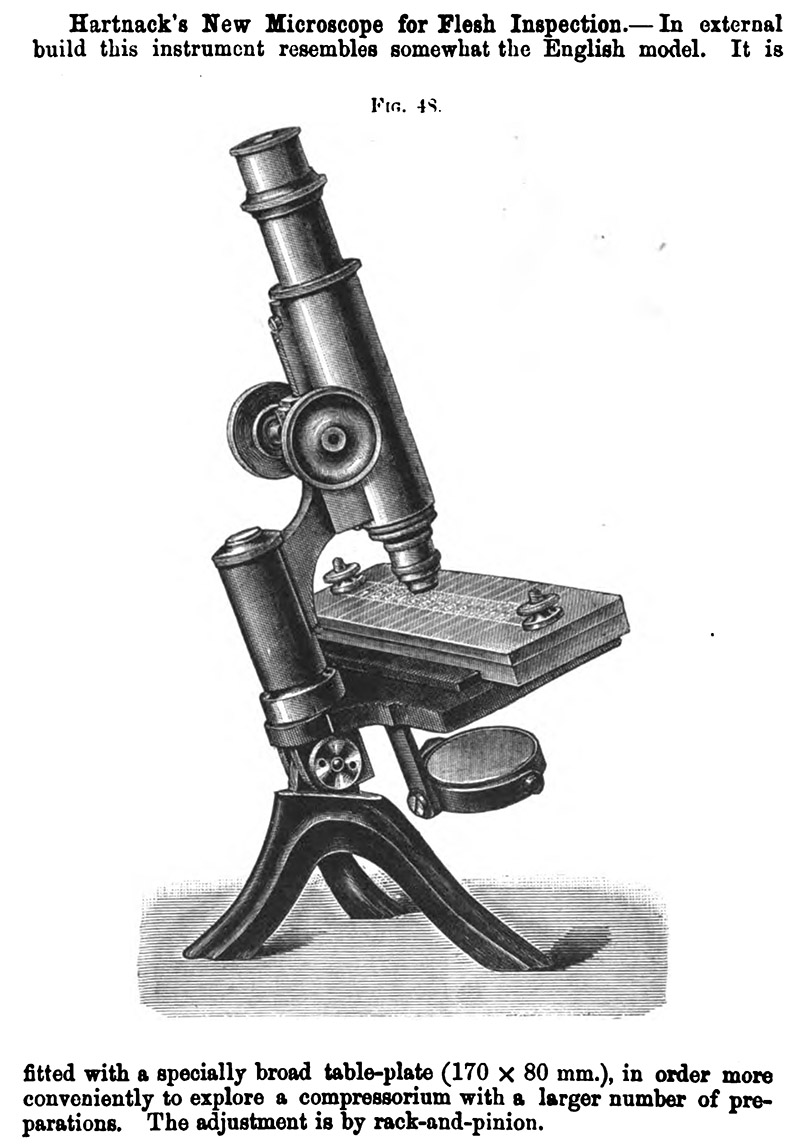

Figure 48.

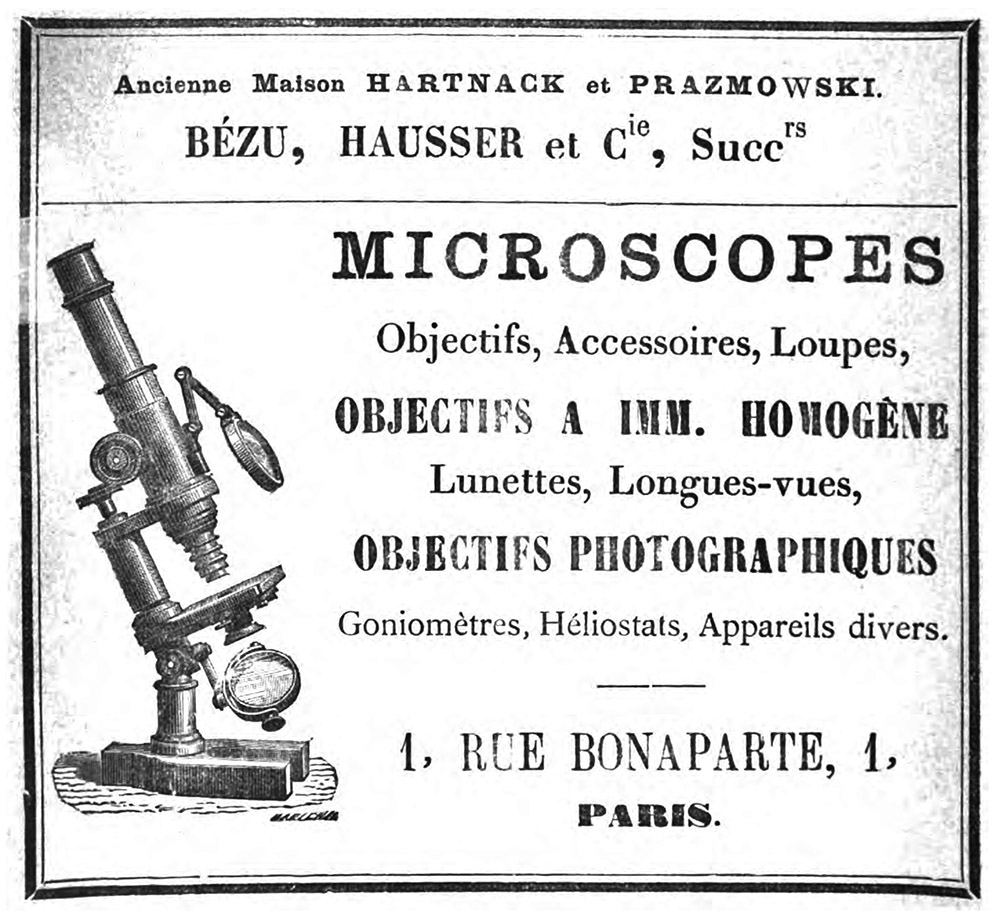

An 1885 advertisement, from “Journal de Micrographie”. “Bézu, Hausser et Cie” began using their name after Adam Prażmowski’s death.

Figure 49.

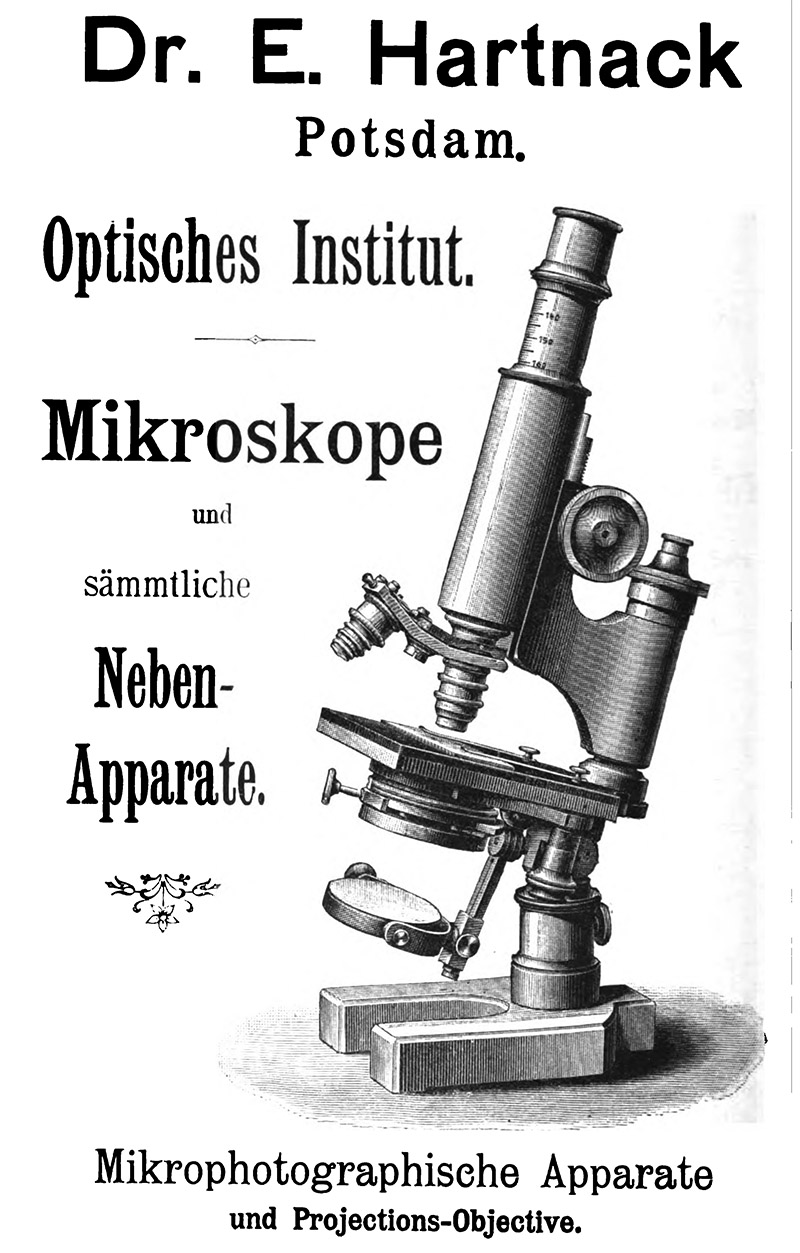

An 1890 advertisement by Hartnack, from P. Baumgarten’s “Jahresbericht über die Fortschritte in der Lehre von den Pathogenen Mikroorganismen”.

Figure 50.

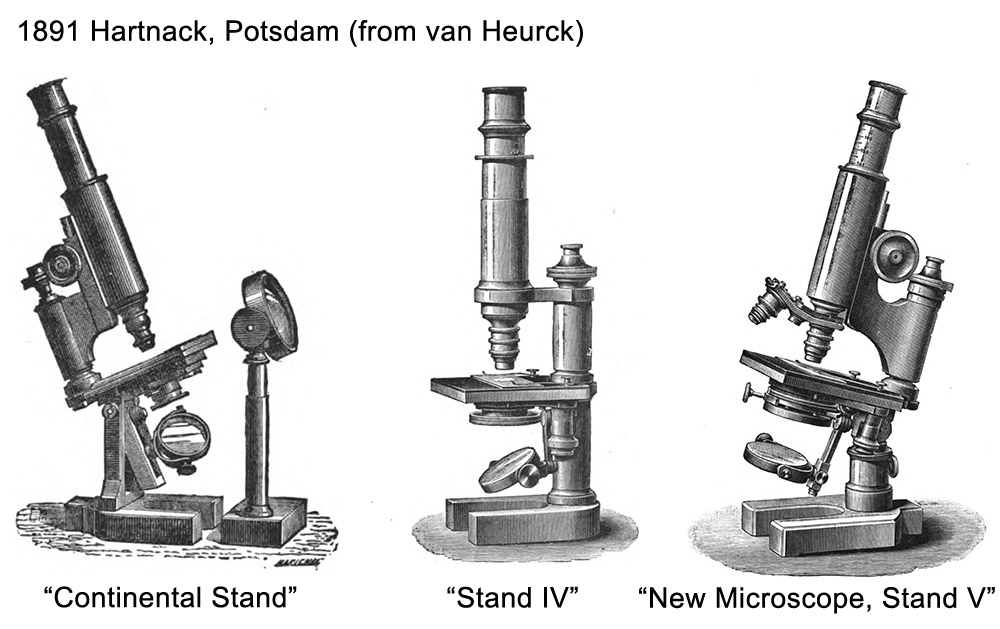

Illustrations of Hartnack microscopes from Henri van Heurck’s 1891 edition of “Le Microscope”.

Figure 51A.

1893 advertisement, from the English translation of Walter Migula’s “An Introduction to Practical Bacteriology”.

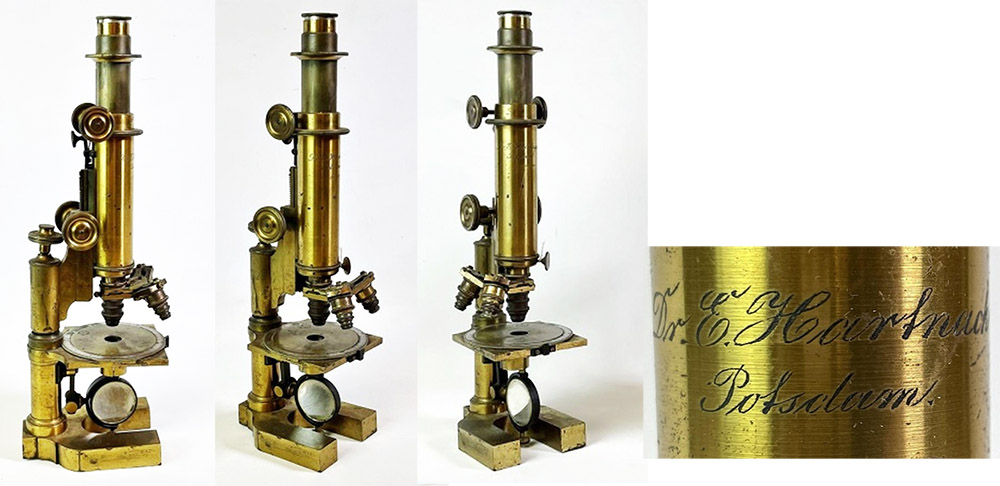

Figure 51B.

ca. 1890s microscope by Hartnack, Potsdam. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

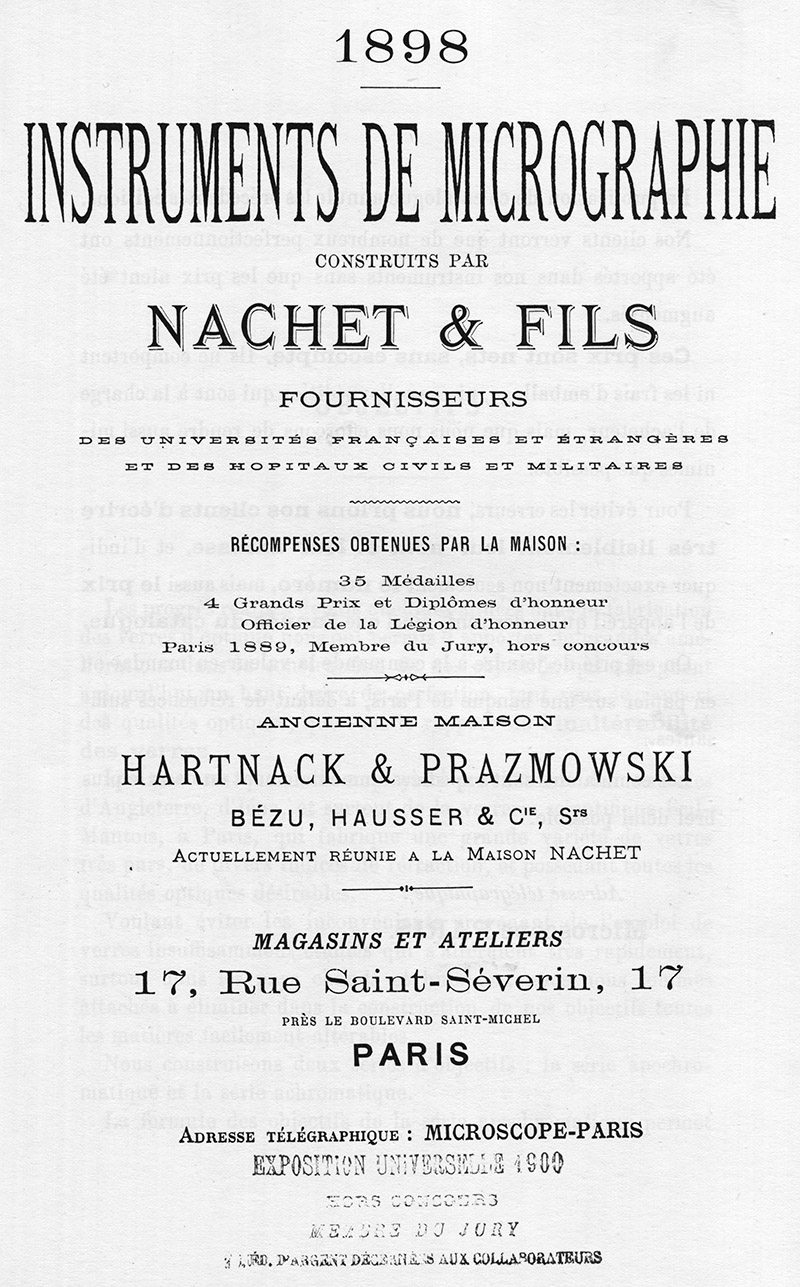

Figure 52.

Cover of a Nachet & Fils catalogue, proudly announcing their 1896 acquisition of the House of Hartnack and Prażmowski from Bézu, Hausser & Co.

Figure 53.

An 1898 description of Hartnack’s new Stand IV-C, from “The Journal of the Royal Microscopical Society”. At that time, the business was run by Edmund Hartnack’s heirs.

Figure 54.

Hartnack’s 1899 stand for inspection of meat (“trichinascope”), from “The Journal of the Royal Microscopical Society”.

Figure 55.

A 1905 advertisement, from “Der Mechaniker”. Hartnack’s firm continued to use his name for several decades after his death.

Figure 56.

1908 advertisements from “The Journal of the Royal Microscopical Society”.

Figure 57.

A model IV A microscope, signed "Hartnack, Potsdam" (see Figure 58). Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Figure 58.

1902 Hartnack microscopes from their catalogue of that year. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from www.microscopy-uk.org.uk/Little-Imp/index.html.

Acknowledgments

My thanks to Timo Mappes, Jeroen Meeusen, Albert Balasse, Barry Sobel, Andrew VonBank, and Allan Wissner for generously providing images of microscopes from their collections, and the staff of the History of Science Museum for details on their holdings.

Resources

Amtsblatt der Regierung in Potsdam (1837) “Der Kaufmann Krl Ludwig Hartnack zu Templin ist zum Schiedsmann für diese Stadt gewählt und verspflichtet worden”

Annuaire Général (throughout the 18th century) accessed through https://gallica.bnf.fr

Archives Commerciales de la France (1878) page 995

von Baumgarten, Paul (1891) Jahresbericht über die Fortschritte in der Lehre von den Pathogenen Mikroorganismen, Harald Bruhn, Braunschweig, advertisement from E. Hartnack

Berthaut, Henri Marie Auguste (1899) La Carte de France, 1750-1898: Étude Historique, Vol. 2, Service Geographique, Paris, pages 64-65, includes photograph of an Oberhaeuser inclinometer

Brisse, Léon (1857) Album de l'Exposition Universelle, page 226

British Medical Journal (1891) “Professor Dr. Edmund Hartnack, the eminent optician, is dead. He died at Potsdam, where his optical institute was. Before 1870 he lived in Paris, but, after the war broke out. he returned to Germany. He is believed to have been the first to introduce immersion into microscopy. His microscopes quickly obtained a European reputation, and it is not too much to say that indirectly we owe to him much of the progress of modern medicine. The University of Bonn made him Doctor honoris causá in 1868; the honorary title of ‘Professor’ was conferred on him by the Government”, page 434

Bulletin de la Société d'Encouragement pour l'Industrie Nationale (1832) Rapport fait par M. Francœur, au nom du Comité des arts mécaniques, sur la machine à limer les surfaces planes et courbes, inventée par M. George Oberhaeuser, ingénieur en instrumens de précision, place Dauphine, n°. 19, page 3

Bulletin des Lois (1837) “MM. Oberhauser (Georges), ingénieur-mécanicien, demeurant place Dauphine, no 19, et Trécourt (Achille), demeurant rue Saint-Dominique-Saint-Germain, no 29 , à Paris, auxquels il a été délivré, le 17 août dernier, le certificat de leur demande d'un brevet d'invention de cinq ans, pour un microscope achromatique vertical à miroir fixe , avec platine à tourbillon , fonctionnant sans déplacement de l'axe optique , par rapport à l'objet soumis à l'observation”, (“Oberhauser [Georges], engineer-mechanic, residing at place Dauphine, no. 19, and Trécourt (Achille), residing on rue Saint-Dominiquc-Saint-Germain, no. 29, in Paris, to whom it was delivered, on August 17 last , the certificate of their application for a five-year patent, for a fixed mirror vertical achromatic microscope, with a tourbillon plate, operating without displacement of the optical axis, with respect to the object subjected to observation”), page 821

Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires des Séances de l'Académie des Sciences (1839) Microscope achromatique à tous grossissements; présenté par MM. Trecourt et Georges Oberhaeuser, Vol. 9, pages 322-323

Description des Machines et Procedes Specifies Dans les Brevets d'Invention (1849) Brevet d’invention de quinze ans, au sieur Oberhaeuser, à Paris, pages 81-84

Dippel, Leopold (1872) Das Mikroskop und Seine Anwendung, F. Vieweg und Sohn, Braunschweig, pages 158-166

Dippel, Leopold (1882) Das Mikroskop und Seine Anwendung, F. Vieweg und Sohn, Braunschweig, pages 432-440

Exposition Universelle de 1855 Catalogue Officiel Publié par Ordre de la Commission Impériale (1855) “Oberhaeuser (J.) & Hartnack (Ed.), à Paris, pl. Dauphine, 19 - Microscopes, dont un pour observations dans le vide au moyen de la machine pneumatique”, page 46

“A Fellow of the Royal Microscopical Society” (1881) “It is now eleven years since Hartnack was - in common with other Prussians during the FrancoGerman war - compelled to leave France. He immediately settled in Potsdam, and there established an optical factory for microscopical work. M. Prazmowski - who had been for several years working with Hartnack - was admitted into partnership, and took entire charge of the house in Pans. The exhibit of microscopes, &c, at the Paris Exhibition of 1878, was by the firm Hartnack and Prazmowski. Since that date the partnership has been dissolved; the Potsdam house remaining exclusively Hartnack's and the Paris house Prazmowski's. It is well known in Paris that to M. Prazmowski's mathematical attainments have been due the improvements developed by the house during the past fifteen years or more. It is also known that his labours have not been limited exclusively to microscopical work; he has been remarkably successful in devising telescope object-glasses of very short focus, portable binocular telescopes, a practical form of Heliostat for physical researches, especially for micro-photography, and, more recently, has been engaged in the construction of spectroscopic and photographic apparatus for M. Janssen. He is now finishing an achromatic object-glass of 13 in. diameter, for which he computed the formula himself”, The English Mechanic and the World of Science, Vol. 32, page 614

Frey, Heinrich (1872) The Microscope and Microscopical Technology, translated by George R. Cutter, W. Wood & Co., New York, pages 629-631

Harting, Pieter (1859) Das Mikroskop, F. Vieweg und Sohn, Braunschweig, page 838

Harting, Pieter (1866) Das Mikroskop, F. Vieweg und Sohn, Braunschweig, pages 148-161

Hartnack (1902) "Preisverzeichnis der Mikroskope un Mikroskopischen Nebben-Apparate von E. Hartnack", accessed through www.microscopy-uk.org.uk/Little-Imp/index.html

van Heurck, Henri (1869) Le Microscope, Ballière et Fils, Paris, pages 79-86

van Heurck, Henri (1885) Bézu, Hausser et Cie., Journal de Micrographie, Vol. 9, pages 371-375

van Heurck, Henri (1891) Le Microscope, Fourth edition, pages 144-149

Jackson, Benjamin Daydon (1906) George Bentham, J.M. Dent, London, pages 135-136

Journal de Chimie Médicale, de Pharmacie et de Toxicologie (1835) “M. Oberhaeusen et Trécourt adressent une lettre à l'Académie, relativement à la proposition faite par M. Arago de consacrer une somme de 11 à 1,200 fr. à l'acquisition de deux lentilles achromatiques en diamant, qui seront construites par M. Bouquet. MM. Oberbaeusen et Trécourt présentent trois lentilles en pierres précieuses, l'une en diamant, l'autre en saphir, et la troisième en rubis. On peut s'en servir comme de loupes simples et comme des microscopes composés. Les lentilles de Flint qui doivent les achromatiser, sont jointes à l'envoi. La lentille de diamant a 9/10 de millimètre; son foyer est de 73 centièmes de millimètre, et sonfoyer est de plus d'un millimètre. Elle a été travaillée sur une sphère de 2 millimètres de rayon. Comme les bords en sont tranchans, l'épaisseur, au centre de la lentille , est exactement de 1/10 de millimètre. Ce peu d'épaisseur fait que la lentille vire sur fi face et peut à peine être distinguée; cependant, quelque petites que soient les dimensions de cet objet, il ne faut pas supposer que le travail nécessaire pour le confectionner soit aussi court; le poli donné aux faces a exigé un travail de vingt heures, avec une roue qui ne faisait pas moins de deux cents fours par seconde, de sorte que la lentille a tourne vingt-quatre millions de fois, sûr elle-même. Les lentilles de saphir et deruLis ont reçu les mêmes dimensions que celle de diamant quant au grossissement. La lentille de diamant, à l'état de simple loupe, donne une amplification linéaire de deux cent dix fois : avec un oculaire composé, il est de deux cent quarante-cinq fois. Dans ce cas, le grossissement de la lentille de saphir est de deux cent cinquante-cinq fois, et celui de la lentille de la rubis de 235”, Series 2, Vol. 1, page 235

Journal de Micrographie (1885) Advertisement from Bézu, Hausser et Cie, Vol. 9

Journal of the Royal Microscopical Society (1882) Hartnack’s drawing appararus (His’s Embryograph), Series 2, Vol. 2, pages 402-404

Journal of the Royal Microscopical Society (1898) New Hartnack microscope, pages 347-348

Journal of the Royal Microscopical Society (1899) Hartnack’s new microscope for flesh inspection, page 216

Journal of the Royal Microscopical Society (1899) Hartnack’s embryograph, pages 223-224

Journal of the Royal Microscopical Society (1908) advertisements from E. Hartnack, multiple issuse

The Lancet (1891) “The death is announced at Potsdam of the well-known optician, Professor Edmund Hartnack, with whose microscopes everyone is familiar. He commenced his manufacture of optical instruments in Berlin, but subsequently removed to Paris. Political feeling there, however, drove him out of France in 1870, and since that time he has been living in Potsdam. The University of Bonn conferred an honorary doctor's degree on him in 1868, and the Minister of Education granted him the title of professor in recognition of the invaluable services he had rendered to science”, page 450

Laussedat, A (1898) Aperçu Historique sur les Instruments et les Méthodes, Annales du Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers, Series 2; Volume 10, pages 128-178 (engraving of an Oberhaeuser inclinometer on page 139)

Mandl, Louis (1839) Traité Pratique du Microscope, J.B. Baillière, Paris, pages 12, 27, and 41-42, and Plate 2

Marriage record of Edmund Hartnack and Johanna Maria Louise Kleinod (1855) Anspach, Bavaria, accessed through ancestry.com

Mayall, John (1885) Cantor Lectures on the Microscope, Society of the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce, London, page 93

Der Mechaniker (1905) Advertisement from E. Hartnack, Vol. 13, advertising section in rear

Medical Times and Gazette (1868) The Jubilee of the University of Bonn, page 198

Medical Times and Gazette (1875) Advertisement from J. Swift, February 13 issue

Migula, Walter (1893) An Introduction to Practical Bacteriology, Translated by M. Campbell, edited by H.J. Campbell, Swan Sonnenschein & Co., London, advertisement from E. Hartnack

The Lancet (1891) “The death is announced at Potsdam of the well-known optician, Professor Edmund Hartnack, with whose microscopes everyone is familiar. He commenced his manufacture of optical instruments in Berlin, but subsequently removed to Paris. Political feeling there, however, drove him out of France in 1870, and since that time he has been living in Potsdam. The University of Bonn conferred an honorary doctor's degree on him in 1868, and the Minister of Education granted him the title of professor in recognition of the invaluable services he had rendered to science”, page 450

Les Mondes Revue Hebdomadaire des Sciences (1868) Nécrologie, Vol. 16, pages 136-137

Nachet et Fils (1898) Instruments de Micrographie

Nias, J.B. (1893) On the development of the continental form of microscope stand, Journal of the Royal Microscopical Society, pages 596-602

Osler, William (1876) Introductory remarks to, and synopsis of, practical course on institutes of medicine, Canada Medical and Surgical Journal, Volume 4, pages 202-207

Pharmaceutische Rundschau (1891) Edmund Hartnack, Vol. 9, pages 98-99

Rapports du Jury Mixte International (1857) MM. Oberhaeuser et Hartnack, Vol. 1, page 431

Rutherford, William (1875) Outlines of Practical Histology, J. & A. Churchill, London, pages 1-2

Seeberger, Max (1999) Oberhaeuser, Georg, Neue Deutsche Biographie 19 (1999), S. 385 f., https://www.deutsche-biographie.de/pnd117076082.html

Strebel, Lorenz Friedrich (1868) Rede bei der feierlichen Preise-Vertheilung am 14. August 1868, https://books.google.com/books?id=ew1FAAAAcAAJ

La Topographie de la Suisse, 1832-1864: Histoire de la Carte Dufour (1898) “Dufour commanda, en outre, au mécanicien Oberhauser h Paris, et par l'intermédiaire du général Pelet, chef du dépôt de la guerre, trois ‘boussoles à éclimètre’, au sujet desquelles il donna les instructions suivantes: ‘Boussole à éclimètre, de forme circulaire”, Le Bureau Topographique Fédéral, Berne, page 121

Trutat, Eugène (1883) Traité Élémentaire du Microscope, Gauthier-Villars, Paris, pages 131-137

Vierhaus, Rudolf ed. (2011) Hartnack, Edmund, Deutsche Biographische Enzyklopädie, Vol. 2, page 467

Waller, Bryan Charles (1881) An Investigation Into the Microscopic Anatomy of Interstitial Nephritis, E.& S. Livingstone, Edinburgh, page 3