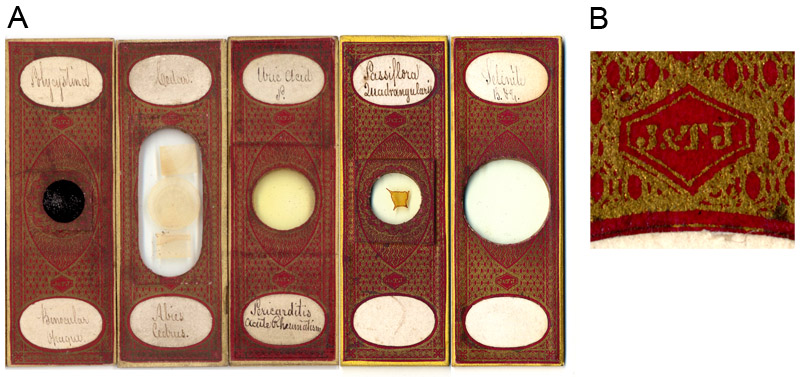

Figure 1. (A) Examples of papered microscope slides made by J&TJ (B) Their initials appear in small hexagons above and below the specimen.

In Search of the Victorian-era Microscope Slide Makers “J&TJ”

by Brian Stevenson and Stanley Warren

last updated September, 2014

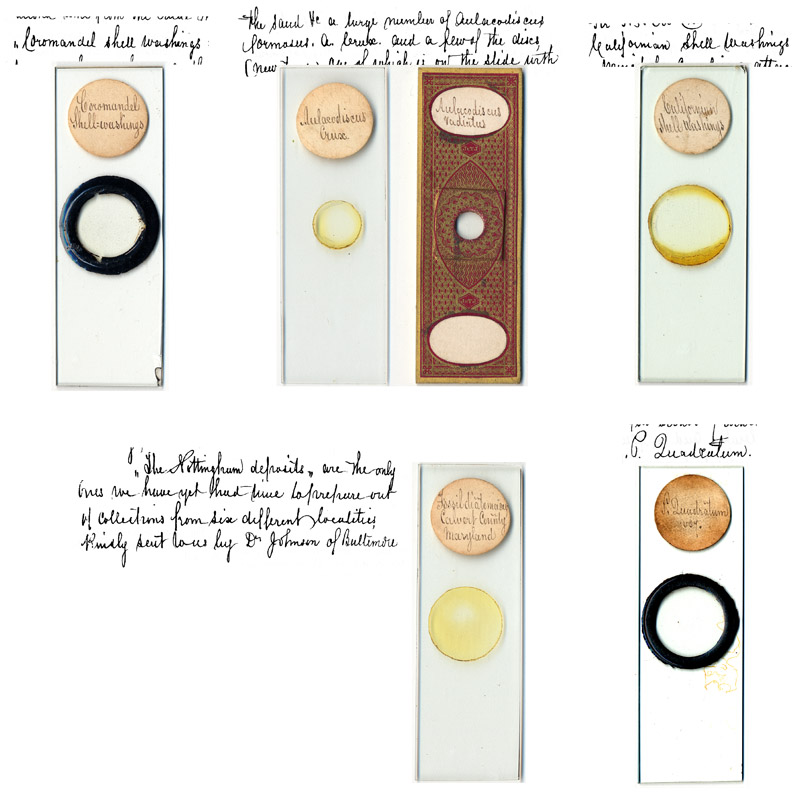

Among the many high quality slide preparers of the mid-19th Century are “J&TJ”. Most of their slides are readily identified by red patterned papers that include small hexagonal lozenges bearing these initials (Figure 1). Other slides with labels written in the same hand are found occasionally, without either paper covers or the maker’s name (Figure 2). Slides by J&TJ often display highly skilled craftsmanship (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

(A) Examples of papered microscope slides made by J&TJ

(B) Their initials appear in small hexagons above and below the

specimen.

Figure 2.

Center, an unpapered microscope slide of “Heliopelta”, bearing the same handwriting as that appearing on J. &T. J. slides.

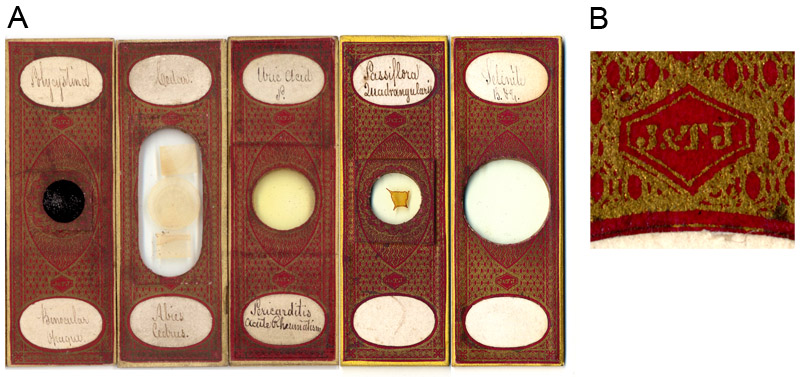

Figure 3.

A J&TJ dry mount of arranged diatom frustules.

Dating J&TJ microscope slides

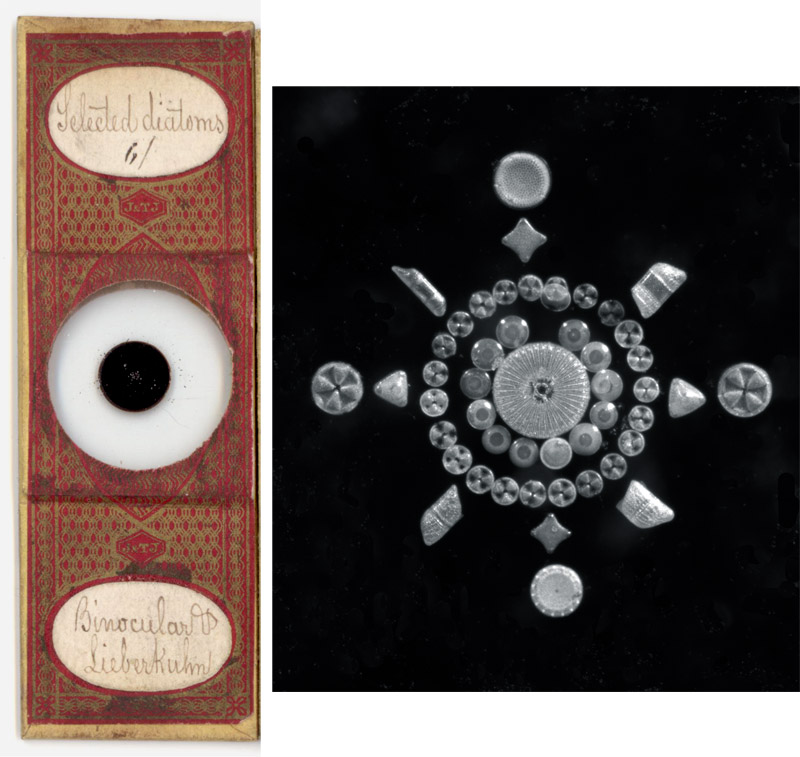

On occasion, J&TJ slides are found that carry secondary labels of microscope retailers (Figure 4). Noting that the trade labels on the illustrated examples are upside down relative to the specimen description labels, these were probably either originally intended for a different market or re-sales of used slides. The microscope firm of Smith, Beck and Beck relocated from 6 Coleman Street to 31 Cornhill during early 1863. Thus, the J&TJ slide-making operation can be confidently dated to 1863 or earlier.

Figure 4.

Slides by J&TJ with secondary labels of Smith, Beck and Beck.

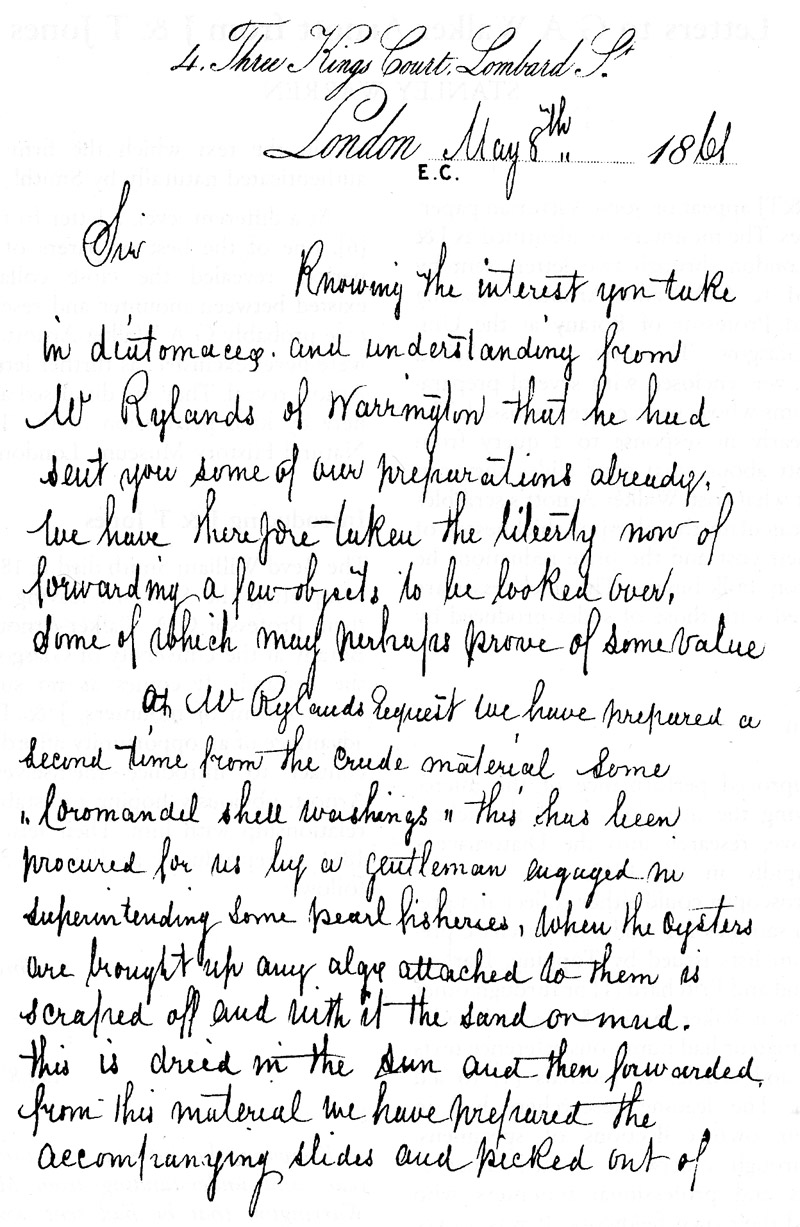

J. and T. Jones

A major step towards identifying J&TJ came with the discovery of two letters sent in 1861 to the noted diatomist George A. Walker-Arnott (Figures 5 and 6). These offered diatom slides and mounting materials, were signed “J. and T. Jones”, and were written on notepaper addressed as from 4 Three Kings Court, Lombard Street, London (also known as Three King-court). The contents of the letters were discussed in detail by Stanley Warren in the Quekett Journal of Microscopy, 2002.

Similarities between the writers’ initials, handwriting, and description of contents suggest that J. and T. Jones, of Three Kings Court, were the makers of J&TJ microscope slides (Figures 5, 6 and 7). Complicating matters, the letters were dated May 8 and August 7, 1861, yet neither the April, 1861 census of England nor the 1861 London Street Directory list anyone named Jones at that address. No additional evidence has been located that directly connects either J. and T. Jones or 4 Three Kings Court to microscopy. However, two men with initials of J. and T. Jones operated businesses adjacent to Three Kings Court during the time of J&TJ’s operation. Following, we present evidence suggesting that these preparations may be attributed to two Victorian entrepreneurs, Joseph and Theodore Jones.

Figure 5.

The May 8, 1861 letter from J. and T. Jones to G.A.

Walker-Arnott

, offering to provide various diatoms. Figure 7, below,

illustrates several microscope slides of specimens named in the letter or

associated with it, and that may be attributed to J&TJ.

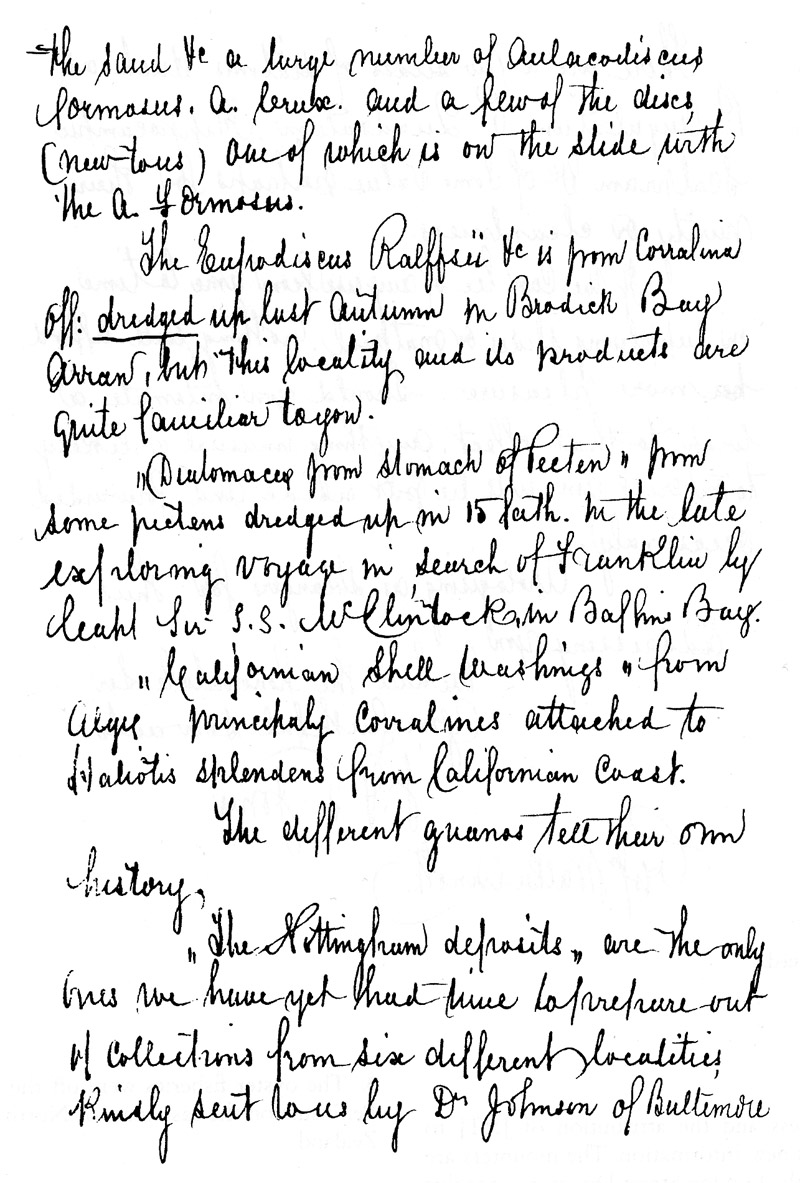

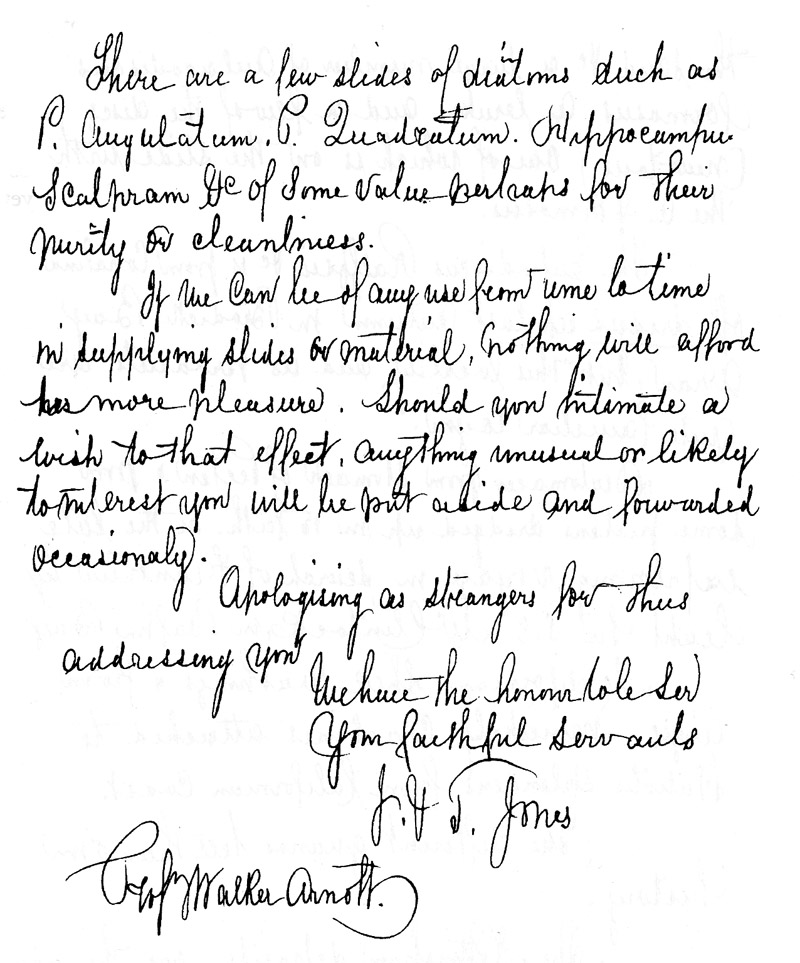

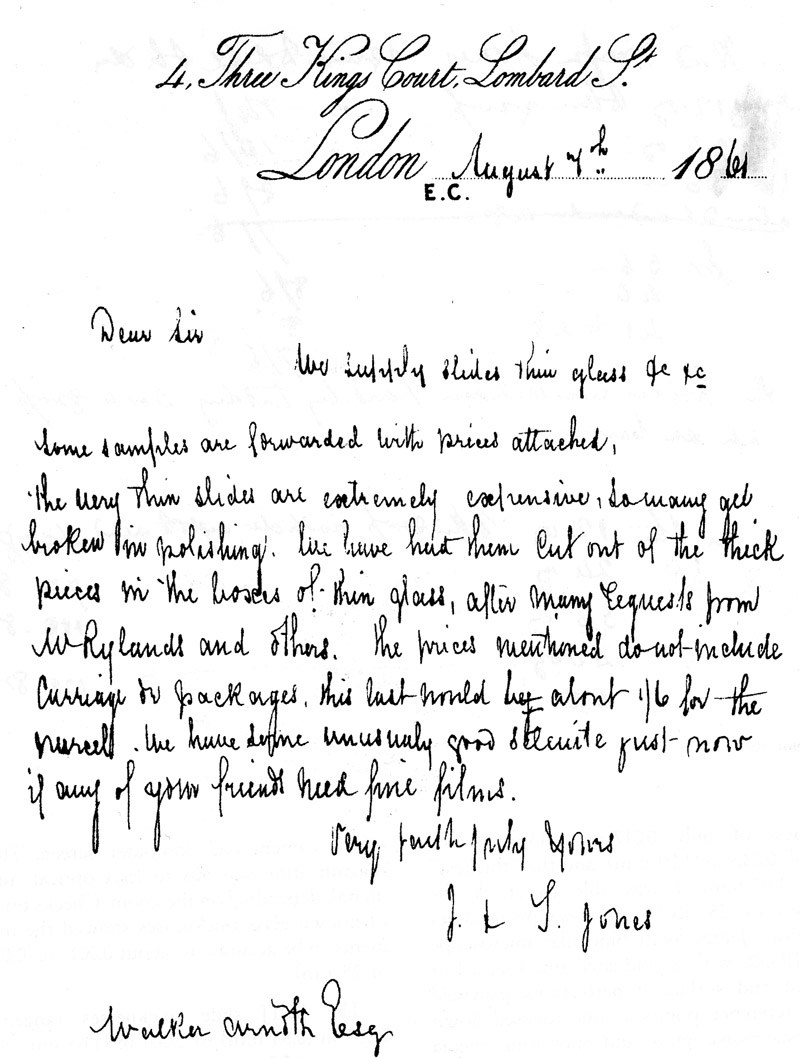

Figure 6.

A

second letter from J. and T. Jones to G.A.

Walker-Arnott, dated 7 August, 1861.

This letter offered to provide thin glass, for use as cover slips.

Figure 7.

Microscope slides attributable to J&TJ, alongside excerpts from the

May 6, 1861 letter that describe the same or similar preparations. The

handwriting in the letter bears some similarities to that on J&TJ slides,

although we are uncertain whether they are from the same person.

4 Three Kings Court

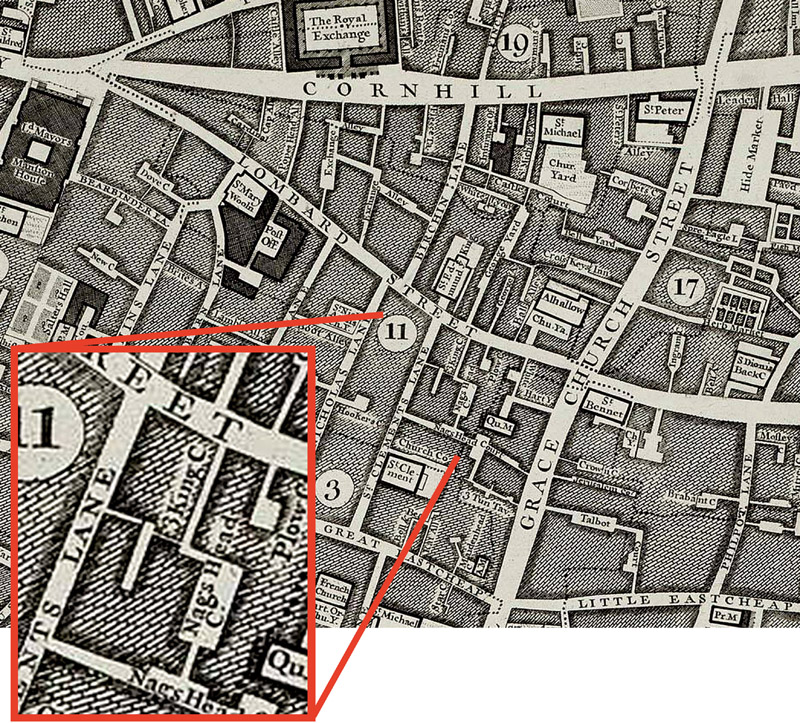

Three Kings Court was one of several narrow lanes or closes running off fashionable Lombard Street in Victorian Central London (Figures 8, 9 and 10). Lombard Street was an early banking center on London, granted to goldsmiths/bankers from Lombardy during the reign of King Edward I (1272-1307). Goldsmiths historically also served as bankers. Three King Court was named for an early business whose symbol was the Three Magi. The Court was some 20 yards east of the junction with Clements Lane (also known as St. Clement’s Lane). The Court led back through Nag’s Head Court to Clements Lane and formed one side of a rectangular area of property some 20 yards in width by 27 yards in depth (Figure 8). The Court no longer exists, but in an early view looking east along Lombard Street (Figure 10), the Court was located just beyond the Church of St. Edmund King, on the opposite (south) side. The view shows the substantial nature of the properties fronting onto Lombard Street while behind, in the Court itself, buildings of a more commercial nature rose to five storeys.

Figure 8.

A Victorian-era map of central London. The inset

highlights the Three King Court – Clements Lane – Lombard Street area. The

general appearance of the area in the mid-1800s was probably not much different

than this 1598 description by John Stow, “But now for the South side of Lombard

Street. Betwixt Grasschurch Street and St. Clement’s Lane, are these Courts and

Alleys, viz. White Hart Court, which hath a Passage through an Entry, into

another Court so called, which leadeth into Grasschurch Street, a Place well

inhabited by Wholesale Dealers, and most by Quakers, where they have their

Meeting-house… Plough Yard hath a good Free Stone Pavement, and the Houses well

built and inhabited. Three Kings Court, well inhabited by Wholesale Dealers and

others. Out of this Court is a Passage into two others, the one leading into

St. Clement’s Lane, narrow and ordinary; but the other is large and open, and

well Tenanted; and this Court hath a Passage into Nags Head Court, which is

long and large, and another Passage into St. Clement’s Lane”.

Figure 9.

Lombard Street (on the right) and Cornhill (on the

left), from the Poultry, circa 1830. The enigmatic wagon with “Jones” on the

tarpaulin, turning into Lombard Street, was owned by Jones and Co., an

unrelated business that operated from Temple of the Muses, Finsbury Square. The

spire of St. Edmund the King can be seen rising over Lombard Street.

Figure 10.

Lombard Street, circa 1849. St. Edmund the King is

on the left. The entrance to Clements Lane is at the streetlight, on the right

side of the street, across from the church. The perfume business of Hughes and

Jones was located on the near corner of Lombard and Clements. The entrance to

Three Kings Court was some 20 yards (ca. 20 meters) beyond that, possibly the

taller archway just beyond the streetlight. To judge from maps, Three Kings

Court was probably only a couple of yards/meters wide. The church in the

background is the now-demolished St. Benet Gracechurch.

The United Kingdom’s 1861 census was taken on Sunday, 7 April, just one month before the first of our two letters was written to Walker-Arnott. It recorded those actually in residence in Three Kings Court on that day. No.4 was occupied by 71-year old John Hill, his wife, two daughters and three sons, plus one boarder. The Hill family also lived there at the time of the 1851 census, at which time they had three boarders. John Hill was a brush maker, a trade his eldest son had also taken up by 1861. The premises were presumably large enough to house not only this grown-up family and a boarder but also the brush making business. Judging from the presence of three boarders in 1851 but only one in 1861, the house likely had sufficient spare capacity to house a slide preparing business. However, the Jones were not listed as occupants on that census day. Thus, two key sources of information - the 1861 Street Directory and the 1861 Census returns – did not conclusively identify the J. & T. Jones of No.4 Three Kings Court.

Much had changed by the time of the next census, in 1871. Three Kings Court was no longer listed, the Hill brush making business and, with it, any Jones slide making business had gone. The Hill family was traced to 70 Stoke Newington Road, Hackney, but both the father and the youngest son had died, the oldest son was now head of the household, and he and his younger brother were employed as clerks. Further searches for information on the two surviving Hill sons failed to identify any interests in microscopy or natural history, and it seems likely that neither had been directly involved in slide preparation. What had happened at Three Kings Court?

Among the other businesses in Three Kings Court was the large cosmetic company of J. Gosnell at No.12, one of three such companies in the immediate area. The others were Price & Co., subsumed by Hughes and Jones at 28 Lombard Street and 39 Clements Lane, and Patey and Co. at 37 Lombard Street. Together they formed a mini centre for perfumery and cosmetics. It is very likely that the brush making Hill family were part of that industry, manufacturing brushes as cosmetic and toiletry accessories, rather than as sweeping appliances. Advertisements from these perfumers often mentioned that they sold brushes.

Disaster befell Three Kings Court just before midnight on 27th November, 1865, when fire broke out in the Gosnell factory at No.12. Although 12 appliances rushed to the scene, there was little prospect of reaching and containing the fire. The Times (London) reported that, “the building of five floors was burnt out to the roof; the staircase was destroyed, and the rest of the house and contents most severely injured by fire and water… Several other houses in the vicinity were considerably damaged by fire, water and breakage”. Renovations in the area led to demolition of Three Kings Court in late 1866/early 1867. Street improvements included “permanent stopping up of … any passage between Plough-court and Three King-court … Three King-court and the passages into the same from Lombard-street and Nag’s Head-court …(and) the passage from Clement’s lane into Three King-court”.

The “Jones” of the Hughes and Jones perfume business was Joseph Jones, who had also been an employee of Price & Co., their predecessor. Hughes and Jones shared its premises of 28 Lombard Street and 39 St. Clements Lane with a firm of accountants operated by Theodore Jones. We thus had a J.J. and a T.J. operating from the same addresses, in the vicinity of 4 Three Kings Court.

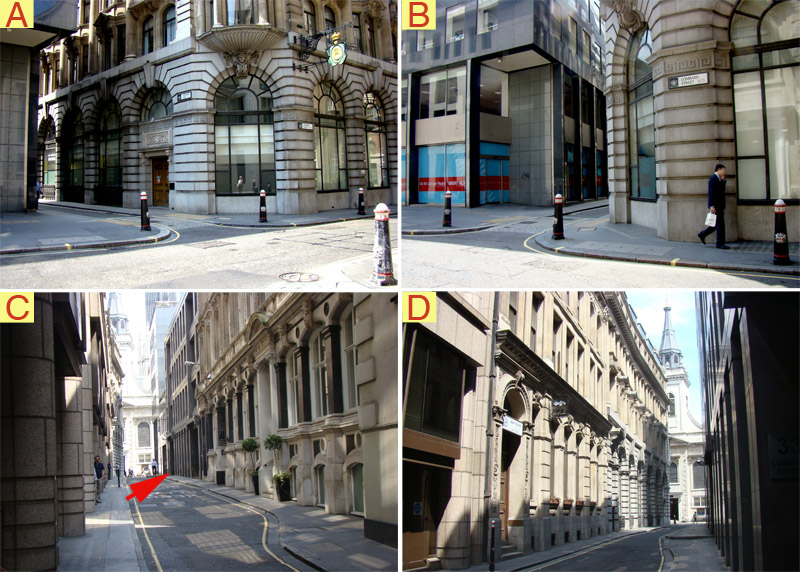

How close were their businesses to Three Kings Court? As mentioned above, the area has been substantially re-developed, with office blocks absorbing smaller buildings both along Lombard Street and in depth behind. These developments were piecemeal, leaving the street pattern and outermost property boundaries unaltered. A large new block would incorporate a numbered run of properties and might simply take one of those numbers for its address. Other than that, the street numbers run as they did in the 1850s/60s period. Walking from the Bank of England eastward along Lombard Street (in the direction illustrated in the ca. 1849 woodcut shown in Figure 10), the numbers increase sequentially on the south (right-hand) side and then continue increasing back on the north side to the Bank of England. Clements Lane intersects Lombard Street between numbers 28 and 29. This put our perfumer and accountant businesses on the right-hand corner, when facing down Clements Lane (Figure 11 A and B). If one then turns into Clements Lane, the numbers increase sequentially on the west side and continue increasing back to Lombard Street on the east side. No.39 was the last property before one reached No.29 Lombard Street. Thus the Jones’ two business premises were separated only by the narrow width of the Lane. The same numbering system would have been true for Three Kings Court so No.4 was on the west side and back to back with properties on Clements Lane, including No.39. Of course we do not know the exact disposition of the properties or what internal passageways might have run through them but it is possible that Hills’ brush making and the Jones’ slide preparing businesses were linked under a common roof with the J. Jones perfume and T. Jones accountancy businesses. At any rate, they were all within a few steps of each other.

Figure 11.

Modern views of the Lombard Street-Clements

Lane-Three Kings Court area.

(A).

View from Lombard Street, looking southwest into Clements Lane. The building on

the far corner, dating from 1910, occupies number 24-28 Lombard Street.

Therefore, the Hughes and Jones perfumery at 28 Lombard stood on that corner of

Lombard and Clements.

(B) Another

view of the corner of Lombard and Clements. The second site of Hughes and Jones

occupied 39 Clements Lane, which was just back from Lombard, on the same side

of Clements as the modern, blocky building.

(C) View from Clements Lane, north toward Lombard Street, with St.

Edmund the King church opposite. The entrance to Three Kings Court from Clements

Lane would have been in the vicinity of the red arrow.

(D) Another view along Clements Lane, toward Lombard Street.

Having established that Joseph and Theodore Jones operated businesses adjacent to 4 Three Kings Court, who were these men?

Joseph Bowen Jones was born in 1817 in Swansea, Wales. He had moved to London by 1841, being recorded in that year’s census as living at 28 Lombard St. His occupation was reported to be “traveller”, most likely a travelling salesman in perfumes and cosmetics because also at that address were a perfumer, Rees Price, his wife Elizabeth, and a servant. As given in greater detail in Appendix 1, Price had been in partnership with Gosnell at 12 Three Kings Court, then continued to trade as Price and Co. at 28 Lombard Street. Price sold the export side of his business to Hughes and Jones in 1845. That business operated from both 28 Lombard Street and 39 Clements Lane. Hughes and Jones exported substantial quantities of their goods throughout the world, which would have also enabled importing of items from the Americas, Oceania and other distant locations. Jones’ advertisements stated that he provided brushes, possibly produced by his specialist neighbour, John Hill. The 1851 and 1861 censuses recorded that Joseph, a bachelor, continued to live at 28 Lombard Street. He was involved in a lawsuit in London during 1867, so presumably still lived in the city at that time. He moved back to Swansea, Wales some time later, and died there in 1869.

Theodore Brook Jones was born during 1828 in Kington, Middlesex, England, son of Orlando Jones. Orlando was an entrepreneur who became very wealthy for inventing a method for extracting starch from grains. In 1846, Theodore Jones joined an uncle in an accounting business, and was described as “consulting accountant, & author of Jones’s English system of bookkeeping with important additions, & of rules & tables for the use of building & investment societies, 28 Lombard street, & 39 Clement’s lane”. He was clearly a successful business manager/accountant and he developed a chain of such offices in other parts of the country. In addition to wealth, he inherited his father’s enthusiasms and invented a “silent alarum bedstead” which excited much interest at the 1851 Great Exhibition. His accounting business did not tie him to London, and he was often recorded as living in distant locations. He married Euphemia Turnbull in Glasgow in 1860 and they spent the first part of 1861 at the baths in Matlock, Derbyshire. Their first son, Theodore Chase Jones, was born there in February, and they were still at a Matlock hotel on the census night of April 7, 1861. Theodore and family moved away from the London area in 1870 and he died in 1920 at the age of 93. More comprehensive details on his life are given in Appendix 2.

Discussion.

We know through surviving letters to the noted diatomist George Walker Arnott that, in 1861, J. and T. Jones operated a business at 4 Three Kings Court, Lombard Street, as suppliers of diatom slides and mounting materials. We now know, additionally, that a perfumer, Joseph Jones, and an accountant, Theodore Jones, shared business addresses at both 28 Lombard Street and at Clements Lane. We can show that not only were those two addresses within a few yards of each other, but that the Clements Lane property was adjacent to Three Kings Court. One may conclude that Joseph and Theodore went into partnership and opened up as slide preparers next door to their primary businesses. There are, however, some grounds for hesitation.

We had expected J&TJ to be a family business and were surprised to find that Joseph and Theodore simply shared a very common surname and ran other, separate businesses from the same addresses. We had also expected to identify the slide preparers through the 1861 Street Directory and the 1861 census returns but, instead, both sources showed only that No.4 was occupied by the Hill family of brush makers, who had no known interests in microscopy. An explanation is that the Hills were renting out some space in their building for a business whose proprietors did not live on the premises. Joseph Jones lived adjacent to the Hills, which would have facilitated easy access to the slide production facility.

Joseph and Theodore Jones are our only strong candidates for having been the slide makers J&TJ. However, we have no direct evidence for either Joseph or Theodore being interested in microscopy. Both ran major businesses, so it seems unlikely that either would have the time to produce slides on a commercial scale. Thus, J&TJ may have been a venture to tap into the burgeoning fascination with microscopy, in which they capitalized a premises and employed one or more slide preparer. The letters to Walker Arnott were clearly written by someone in full charge of the business, but we are uncertain whether differences in handwriting of the letters and J&TJ slides indicate that they were written by different people. Theodore, in particular, had the financial resources for such a venture. Noting that he operated a firm of accountants without his daily presence, so too might he have been comfortable with being an absentee partner in the J&TJ firm of slide preparers. Joseph lived and worked adjacent to the J&TJ production facility, where he could easily have overseen slide preparation in addition to his business as a supplier of perfumes and toiletries. Joseph probably had an established business connection with John Hill’s brush manufacturing operation, so it is logical that the Jones would have taken advantage of the room(s) in Hill’s building vacated by the two boarders who moved out after 1851. A slide making operation would not require much space.

We have not identified any advertisements from J&TJ, but they probably had no need to advertise. The correspondences we have suggest they made direct approaches to microscopists, and also relied on word of mouth contacts. Note that both letters mention that they had also been in contact with diatomist Thomas Rylands (Figure 5). As a perfumer, Joseph had world wide contacts and extensive trade outlets for his wares, so why not similar contacts and outlets for slide preparations? Both Theodore and Joseph had close connections to the wealthy classes who, at that time, were very excited about microscopy. In that case there would have been no need to advertise to the masses, no need to list an address and no need to identify themselves other than through discreet initials on their slide papers. Likewise, neither James W. Bond nor John Barnett appear to have advertised their wares, although both produced significant numbers of microscope slides during the 19th century, marked only with their initials. Edmund Wheeler also labeled his earlier slides with his initials only. Strikingly, even when Wheeler had a booming business as a slide preparer, he declared himself in census returns to be a “lecturer on natural philosophy”, a “teacher of sciences”, or a “public lecturer”, and his death record stated that he was a “gentleman”. If Wheeler had not advertised his microscopical preparations and printed his full name on later slide labels, one would never suspect his prolific output as a slide preparer.

J&TJ slides, while not rare, are certainly not as common as those of Wheeler or Barnett, but records suggest that they were in business for only a short time. Between the fire in Three Kings Court of 1865 and the Court’s demolition in 1866, they may have let the business lapse rather than re-start in another location. Neither Joseph nor Theodore would have depended on slide preparing for a living. The expansion of large-scale slide-makers in the field, such as Edmund Wheeler, John Barnett, Charles Topping, and John Norman, may have cut into the profitability of operations such as J&TJ. Meanwhile, Joseph’s health deteriorated and he died four years after the fire. Theodore developed a successful chain of accountancy businesses throughout the island, and left London for good in 1870.

In conclusion, we located strong circumstantial evidence pointing to Joseph Jones, perfumer, and Theodore Jones, accountant, as the partners behind the J&TJ microscopy business. It is likely that one or more employees actually prepared the J&TJ slides. We further suggest that they let that business lapse by the mid-1860s.

Appendix 1: Joseph Bowen Jones

Joseph Jones was born 25 September, 1817 in Swansea, Glamorgan, Wales, son of Joseph and Catherine Jones.

The 1841 census of England found 25-year old Joseph living at 28 Lombard St., London. His occupation was recorded as “traveller”, i.e., a travelling salesman. Also at that address were Rees Price (misspelled as “Rice” in the census record), his wife Elizabeth, and a servant. Price was then recorded as being a “perfumer”, a manufacturer of perfumes and personal toiletries (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Examples of cosmetics pot lids from Rees Price’s perfumery business. He sometimes described the company as “Napoleon Price”, a fictitious name. Note that Price advertised his company to be the successor to Price and Gosnell.

Rees Price had previously been a partner in a perfumery business with John Gosnell, but had sold off his interest in the business to Gosnell. Although Price had pledged not to compete with Gosnell as a condition of dissolving the partnership, Price clearly disregarded that promise (Figure 12). This led to an 1845 law suit by Gosnell’s heirs, which ended in their favor. As part of the settlement, the following announcement was published: “PRICE and GOSNELL'S PERFUMERY. Notice. Executors of the late John Gosnell v. Rees Price, Perfumer, 28, Lombard-street, trading under the firm of Price and Co., and previously under the assumed name of ‘Napoleon Price and Co.’ The Judges in the Court of Exchequer in this day decided in favour of the plaintiff in this case. The defendant, Rees Price, had disposed of his interest in the Perfumery and other trades carried on by the late firm of Price and Gosnell, to the late Mr. John Gosnell (father of the parties now carrying on business under the firm of John Gosnell and Co., 12, Three King-court, Lombard-street), and bound himself, under forfeiture of £5,000, not to commence business within the Cities of London or Westminster, or within the distance of 600 miles from the same, and, notwithstanding this, had carried on business. This action was brought to recover liquidated damages for such breach of contract. —12, Three King-court Lombard-street, Jan. 27, 1845”. This law suit evidently worked, as the 1851 census found Rees Price working as a “licensed victualler” in Pentonville.

Figure 13.

A label from Price and Gosnell (pre-1841) and a pot

lid from John Gosnell and Co, the legal successors to Price and Gosnell.

Joseph Jones purchased part of Rees Prices’ business and remained at 28 Lombard St. His business appears to have been primarily importing and exporting from England (Figures 14 and 15). A German magazine reported in 1849 that “Montpellier House, 28 Lombard-Street London .. This perfume has also become a peculiar favourite in every foreign Court and City”. The 1851 census reported Jones as being a “wholesale perfumer”, living at 28 Lombard along with a servant. The business was then known as Hughes and Jones, described in the 1851 Post Office London Directory as “perfumers to her Majesty, manufacturers of fancy soaps, brushes, &c. importers of essential oils & foreign perfumery”. Prior to 1851, Jones had entered into a partnership with William Phillips Hughes, a relatively wealthy merchant. Hughes did not live at Lombard St. From what we can glean from records, Hughes was probably the money behind the partnership, while Joseph Jones supplied the expertise in perfumery.

Figure 14.

Pot lids from Hughes and Jones’ Reindeer’s Marrow hair dressing.

Figure 15.

An 1859 advertisement from the Daily Southern Cross (New Zealand).

Joseph Jones was still residing at 28 Lombard St. at the time of the 1861 census. J. and T. Jones wrote their letters to George Walker-Arnott on May 8 and August 7, 1861.

Joseph Jones never married. He was involved in a lawsuit in London during 1867, so presumably still lived in the city at that time. He moved back to Swansea, Wales some time later, and died on October 1, 1869 from “hepatic congestion”, “dropsy” and “congestion of lungs”

Appendix 2: Theodore Brook Jones

Theodore Jones was born during the summer of 1828 in Kingston, Middlesex, England, son of Orlando and Anne Jones. Orlando was an entrepreneur who became very wealthy for inventing a method for extracting starch from grains (Figure 16). Arthur Dewing reported, “In 1840, an Englishman, Orlando Jones, patented an improved process whereby an alkali was employed in the recovery of the starch granules. This process shortened the period of manufacture, and enabled the starch maker to obtain a larger yield. The Orlando Jones invention was patented for the United States in 1841 and may be regarded as the basic patent for the present industry. In 1844, Colgate and Company, who had been manufacturing wheat starch in their Jersey City factory, began to apply the Orlando Jones process to corn. The experiment proved satisfactory, and was subsequently adopted by Julius J. Wood and Charles Colgate at their wheat factory in Columbus, Ohio”.

Figure 16.

A label from Orlando Jones’ starch company

In 1846, Theodore Jones became a partner in an accounting business with his Uncle Theodore (Orlando’s brother). The 1851 census found young Theodore at his home, 5 Clapton Square, Hackney. The 1851 Post Office London Directory listed his business as “consulting accountant, & author of Jones’s English system of bookkeeping with important additions, & of rules & tables for the use of building & investment societies, 28 Lombard street, & 30 Clement’s lane”.

Theodore inherited his father’s enthusiasm for inventing. He displayed his “silent alarum bedstead” in the Crystal Palace at the 1851 Great Exhibition. This was remarked upon by many people, including Charlotte Brontë, who noted in a letter “a silent alarum bedstead to turn any one out of bed at a given hour, invented by Mr. Jones of Lombard Street”. Dickens’ Household Words reported, “Here is that extraordinary stroke of genius, the alarum bedstead, - extraordinary, we may be sure, when we are told that ‘the movement of the hand of a common watch will turn any one out of bed at any given hour when attached to this bedstead’ - a resolute act, very impressive to perform at six o'clock on a cold wintry morning”. Jones’ device connected two folding legs of a bed to an alarm clock. When the alarm went off, the legs retracted, inclining the bed and dropping the occupant onto the floor. Presumably for use with servants, the occupant had no choice but to stay up, since the bed was no longer flat.

Theodore Jones married Euphemia Turnbull in Glasgow, Scotland in 1860. They spent part of 1861 at the baths in Matlock, Derbyshire. Their first son, Theodore Chase Jones, was born in Matlock in February, and they were still at a Matlock hotel on the April 7 census night. J. and T. Jones wrote their letters to George Walker-Arnott on May 8 and August 7, 1861.

Jones’ accounting company expanded its business and opened new offices throughout the country. Theodore and family moved away from the London area in 1870. Wendy Habgood reported, “the origin of the firm can be traced back to Edward Thomas Jones, author of English System of Book-keeping (1796). Jones completed his training as an accountant with a Bristol, Avon, merchant in 1788, but then abandoned his accounting ambitions in favour of a coal-mining venture in Monmouth, Gwent, financed by the publication of his book. The mining scheme subsequently ran into serious difficulties and Jones returned to Bristol in 1810 to set up as a coal merchant. In 1821 he resumed his original profession, moving to London where he remained until his death in 1833. The practice was then continued by his son, Theodore. In 1846 Theodore took into partnership his nephew, Theodore Brook Jones, and, in 1867, Arthur James Hill (our note: no relation to the brush-making Hill family). Theodore Brook Jones moved to Harro(w)gate, North Yorkshire, in 1870 and opened offices in Leeds, West Yorkshire, known as Theodore B. Jones & Co, and in Manchester, Greater Manchester, known as Jones Crewdson & Co. Both of these eventually became part of Spicer & Pegler, a predecessor firm of Touche Ross & Co. In 1878 the three offices split into separate partnerships, the London firm adopting the style Theodore Jones, Hill, Velacott & Co in 1884 and to Arthur J Hill, Velacott & Co in 1888”.

Theodore Jones died in 1920, at the age of 93, in Knaresborough, Yorkshire West Riding.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks to Steve Gill and Howard Lynk for insightful comments on this research.

Resources

Allgemeiner Wohnungsanzeiger für Berlin, Charlottenburg und Umgebungen (1849) Note on Montpellier House perfume, page 39

Annual Report for the Year (1851) Registration of copyrights of designs, 1851, Jan. 14, No. 6, Silent alarm bedstead, Theodore Jones, 28, Lombard St., City, London, Vol. 1, page 623

Bracegirdle, Brian (1998) Microscopical Mounts and Mounters, Quekett Microscopical Club, London, page 58Christening record of Theodore Brook Jones (1828), West Hackney Church, Middlesex

Daily Southern Cross (1859) Advertisements for perfumery from Hughes and Jones, 8 Huitanguru page 1 and 6 Hakihea page 2.

Death record of Joseph Bowen Jones (1869), Swansea, Glamorgan, Wales

Death record of Edmund Wheeler (1884) Brighton, England

Dewing, Arthur Stone (1914) Corporate Promotions and Reorganizations, Harvard University Press, page 50

England and Wales census, birth, marriage and death records, accessed through ancestry.co.uk

Gosnell, Jules (accessed 2013) John Price / Price & Gosnell / John Gosnell & Co. (1677-Present), http://www.gosnell.org

Habgood, Wendy (1994) Hill Vellacott (Chantry Vellacott), Chartered Accountants in England and Wales, Manchester University Press, page 139

Household Words (1855) Going further (description of T. Jones’ silent alarum bedstead), Vol. 10, page 44

London Gazette (1866) Lombard Street Improvement, November 20, pages 6169-6170

Matthews, Derek, Malcolm Anderson and J.R. Edwards (1998) The Priesthood of Industry, Oxford University Press, pages 18-19, 39, 49 and 106

The National Archives (accessed April, 2011) Farina v. Hughes. Plaintiffs: Johann Maria Farina. Defendants: William Phillips Hughes and Joseph Bowen Jones. www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/catalogue/displaycataloguedetails.asp?CATLN=7&CATID=-2977286&

Official Catalogue, Great Exhibition (1851) 656 – Jones, T. 28 Lombard St. Inv.—Silent alarum bedstead to turn any one out of bed at a given hour, page 73

Old Bailey Proceedings (1851) Case 444. William Piper, stealing 24 pots of bears' grease, and other articles, value 5£ 18s.; the goods of William Phillips Hughes, and another: to which he pleaded guilty. Aged 40. He received a good character. Confined six months. http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?path=sessionsPapers%2F18510203.xml

Post Office London Directory (1851) page 191 (Clement’s lane, 28 Lombard street to 72 King William street: 39, Hughes & Jones, wholesale perfumers, and Jones Theodore, accountant), page 353 (Lombard street: 28 Jones Theodore, accountant, &c, Price & Co. perfumers, &c, and Hughes & Jones, perfumers), page 519 (Three Kings Court, 32 Lombard st. & 5 Nag’s Head court: 4 Hill John, brush, &c. manfr, 12 Gosnell John & Co. perfumers and Price & Gosnell, perfumers, &c), page 793 (Hill John, brush manfr. 4 Three King ct. Lombard street), page 807 (Hughes & Jones, perfumers to her Majesty, manufacturers of fancy soaps, brushes, &c. importers of essential oils & foreign perfumery, 39 Clement’s lane, & 28 Lombard st), page 826 (Jones Joseph B. wholesale perfumer, see Hughes & Jones) and page 827 (Jones Theodore, consulting accountant, & author of Jones’s English system of bookkeeping with important additions, & of rules & tables for the use of building & investment societies, 28 Lombard street, & 39 Clement’s lane)

The Revised Reports (1845) Citation of Executors of the late John Gosnell v. Rees Price in the case Green v. Price, Vol. 67, pages 791-792

Selected letters of Charlotte Brontë (2007) ed. by Margaret Smith, Oxford University Press, Oxford, page 194

The Shopkeeper’s Guide (1853) Perfumers, Hughes, Wm. P., 28, Lombard-street, City, and Jones, Joseph B., 28, Lombard-street, City, pages 242-243

The Sportsman's Magazine of Life in London and the Country (1845) Settlement notice of the lawsuit Executors of the late John Gosnell v. Rees Price, Vol. 1, page 442

Strype, John (1598, reissued in 1722) A History of London and Westminster, accessed online at http://www.hrionline.ac.uk/strype/index.jsp

Tallis, John and Jacob G. Strutt (1852) Tallis's History and Description of the Crystal Palace, page 118

Transactions of the London and Middlesex Archeological Society (1860) List of members, incl. Hughes, William Phillips, Esq., 24, Harley-street. W., Vol. 1, page 9

Warren, Stanley (2002) Letters to GA Walker-Arnott from J & T Jones, Quekett Journal of Microscopy, Vol. 39, pages 379-390