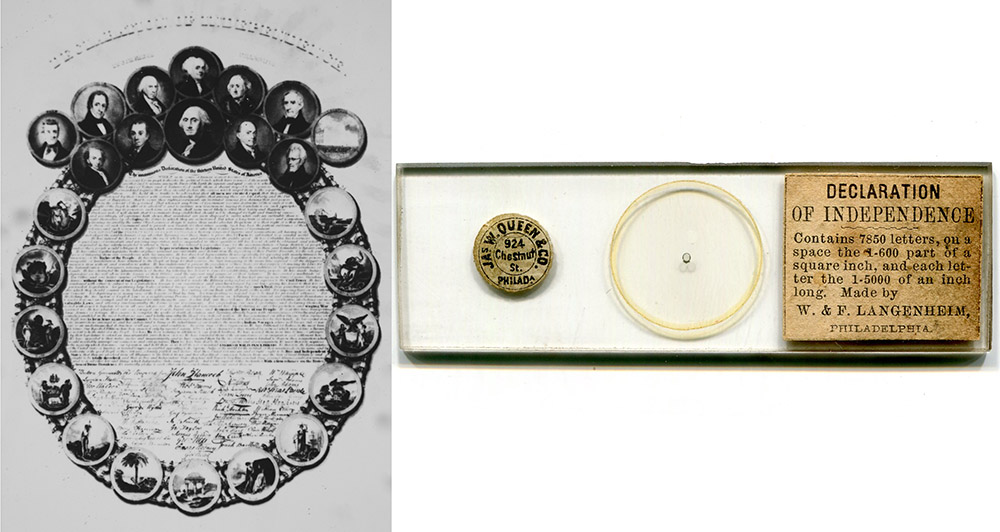

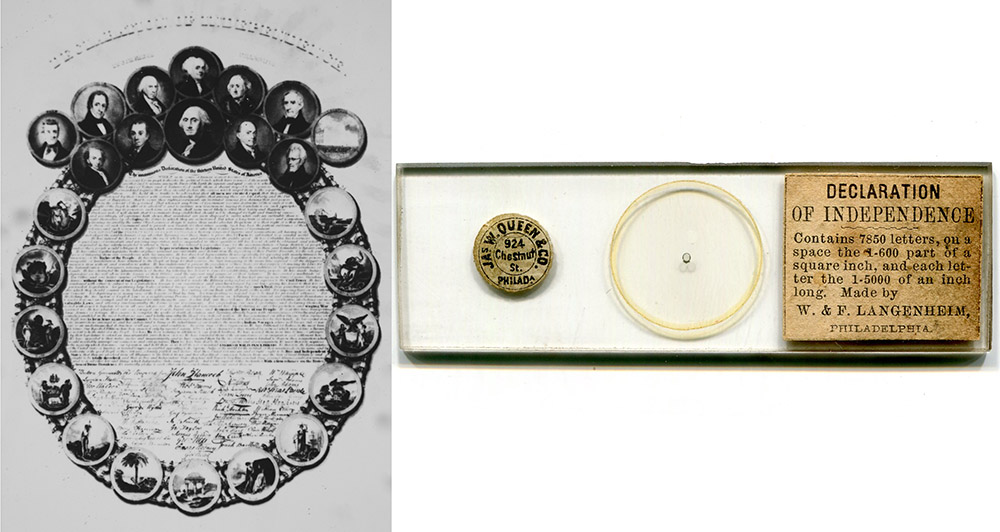

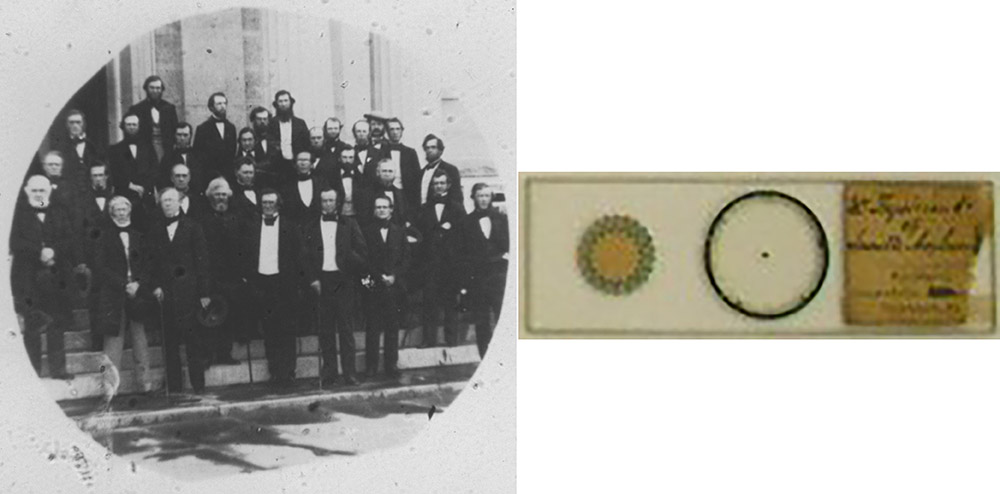

Figure 1. Microphotographs by W. & F. Langenheim, ca. 1855-1870s. The Philadelphia firm of James W. Queen & Co. was incorporated in 1858.

William Langenheim, 1807 - 1874

Frederick Langenheim, 1809 - 1879

W. & F. Langenheim

Langenheim & Brecker

Langenheim & Co.

Langenheim, Loyd, & Co.

American Stereoscopic Company

by Brian Stevenson

last updated June, 2023

Brothers William and Frederick Langenheim were pioneering American photographers. During the early 1840s, they obtained daguerreotype photographic equipment and opened a business in Philadelphia. One of their most significant contributions to photography was to adapt “talbotype” photography, invented by William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877) and which used paper for both the negative and positive, to instead capture the negative and subsequent positive on glass. They called this process “hyalotype”, and displayed examples at the 1851 International Exhibition in London. The hyalotype process was then adapted by Louis Jules Duboscq-Soliel (1817-1886) to produce glass slides for stereoscopes. It may also have facilitated John Benjamin Dancer's ca. 1853 development of microscopical photographs (microphotographs) on glass slides.

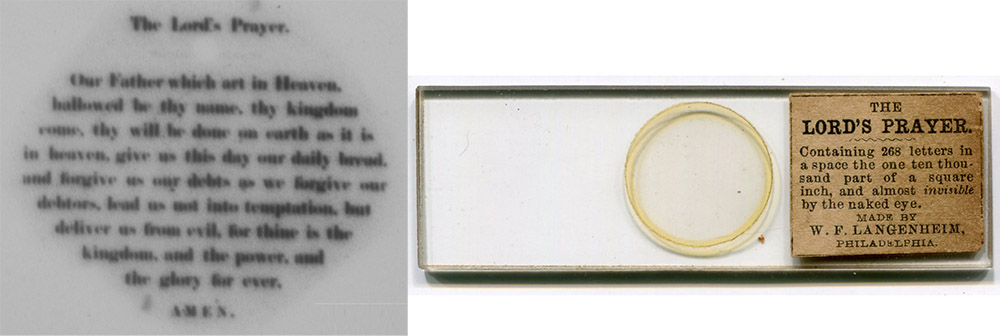

By 1857, the Langenheim brothers were also producing microphotographs. Their Philadelphia business was in flux at the time, having dissolved into bankruptcy during early 1851, then re-establishing in 1854. They also established two companies to distribute their products: The American Stereoscopic Company and Langenheim, Loyd, & Company. It also appears that William may have produced microphotographs on his own, during the time of the brothers’ business breakup. Langenheim microphotograph slides can be found with various names on the labels (Figures 1-4). They are quite rare, and often command very high prices at auction.

Figure 1.

Microphotographs by W. & F. Langenheim, ca. 1855-1870s. The Philadelphia firm of James W. Queen & Co. was incorporated in 1858.

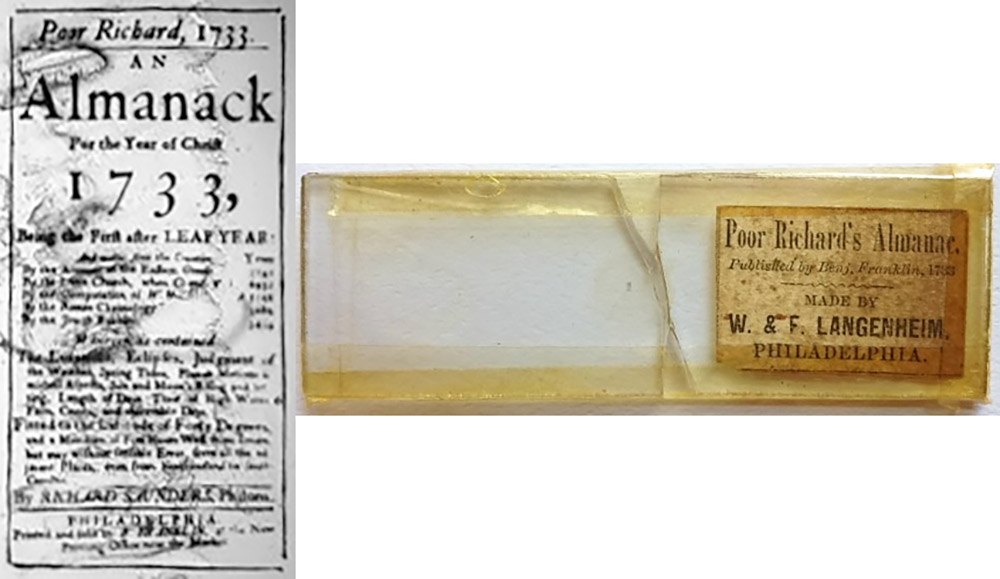

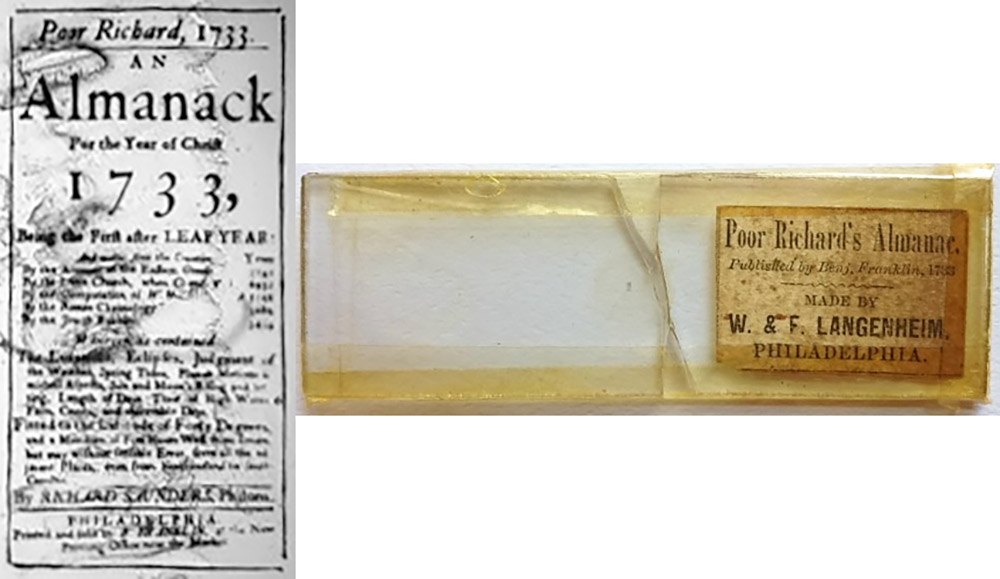

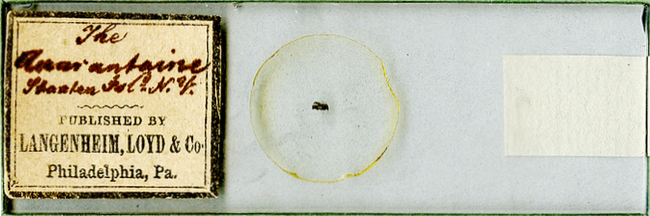

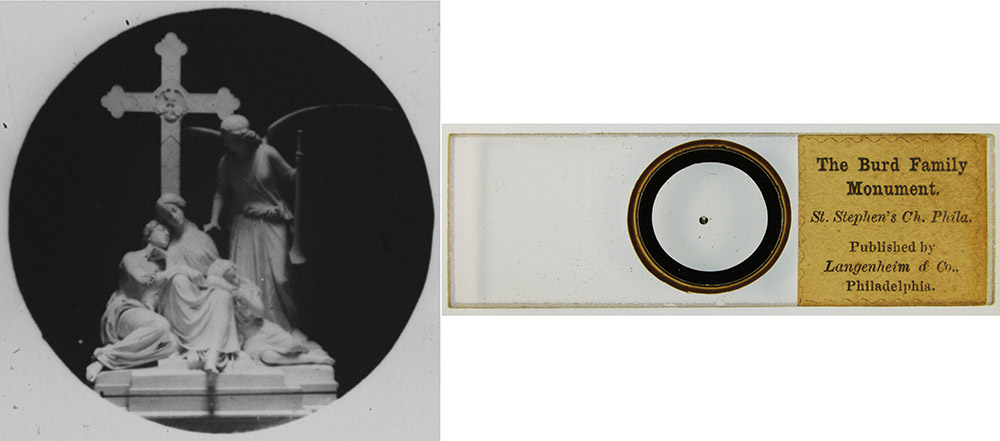

Figure 2.

Microphotograph by W.F. Langenheim. This may date from the mid-1850s and have been produced by William (full name Ernst Wilhelm Fredrich Langenheim), before he and Frederick re-established their joint business.

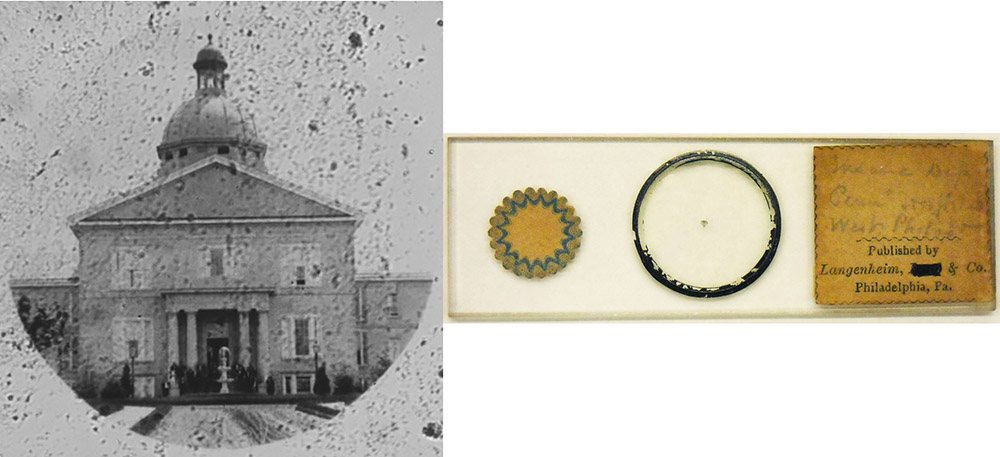

Figure 3.

Microphotographs from Langenheim, Loyd, and Company. This business was formed ca. 1857 to distribute the Langenheim’s magic lantern slides and William Loyd’s projectors. It appears to be synonymous with the American Stereoscopic Company. The business probably was dissolved in the early 1860s. Slides with Loyd’s name crossed out were sold after the partnership ended.

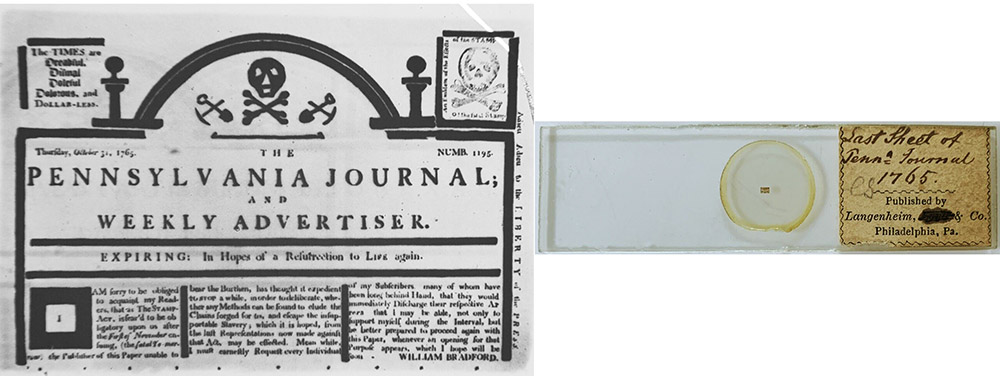

Figure 4.

Microphotograph labeled by Langenheim & Company. Probably made after the end of Langenheim, Loyd, and Company,during the 1860s.

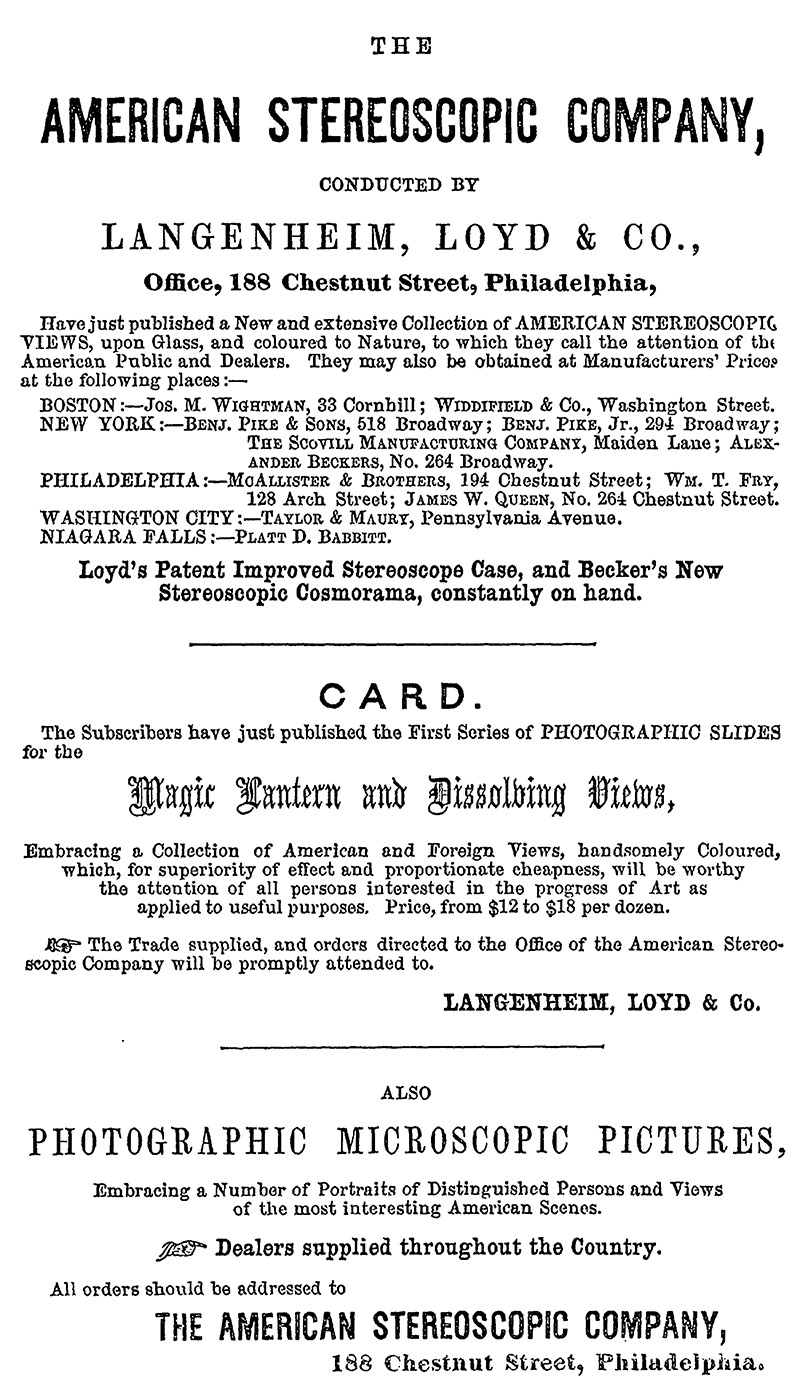

Figure 5.

1857 advertisement for microphotographs, from M.P. Simons' "Plain Instructions for Colouring Photographs in Water Colours and India Ink".

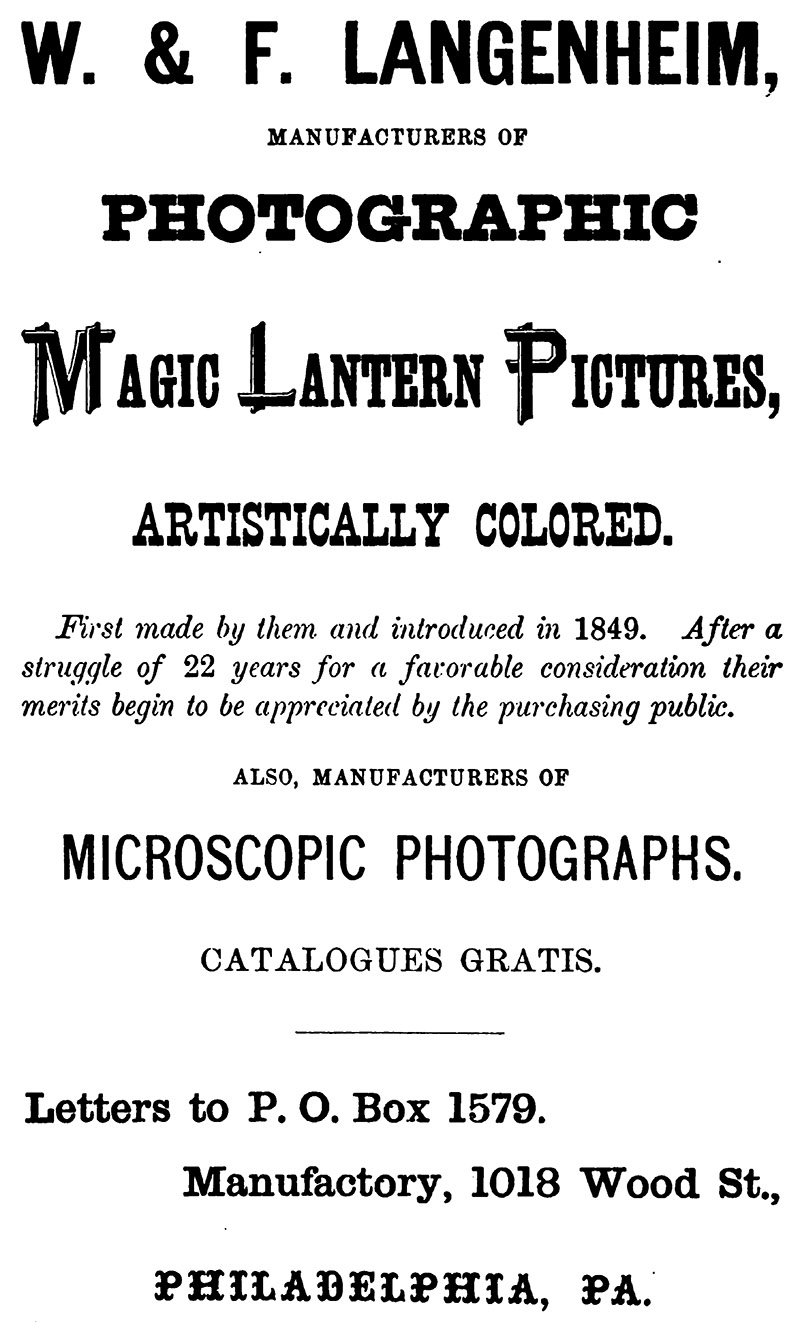

Figure 6.

1871 advertisement for microphotographs, from "Photographic Mosaics".

The Langenheim brothers were both born in Brunswick, Saxony (now part of Germany). Ernst Wilhelm Fredrich Langenheim (later “William”) was born February 23, 1807, and Friedrich Langenheim (later “Frederick”) was born on May 5, 1809. I will use their Americanized names in this essay.

William studied law at the University of Gottinen. He left Germany in 1834, possibly due to the political unrest of that time.

He landed in the USA in Baltimore, then accompanied a party of German emigrees to the Texas region of Mexico. War between the Texas settlers and the Mexican government broke out in 1835. Wiliam joined the Texas volunteer army, and fought to expel Mexican troops from San Antonio in the Battle of Bexar, October-December, 1835.

In February, 1836, William accompanied Francis Johnson on an expedition to acquire horses for the Texan army. On February 27, 1836, the group of approximately 40 men was surprised at San Patricio by General José de Urrea’s army, and were quickly defeated. William was taken prisoner, and held captive for almost a year.

He was released on January 29, 1837 in a prisoner exchange. William then traveled to New Orleans and Saint Louis, looking for work. Unsuccessful, he joined the Second Dragoons of the regular US Army in New Orleans on May 15, 1837. He served in Florida, during the wars against the Seminoles. William was discharged on May 14, 1840, with the rank of sergeant. His discharge record reported that he was an imposing 6 feet ½ inch (1.85 meters) tall, with blue eyes and red hair.

William then moved to Philadelphia to join his younger brother, who apparently had recently arrived in the USA. Little is known of Frederick’s early life, other than he was employed in agriculture. The two brothers took work with a German-language newspaper.

In a series of coincidences, one of the Langenheims’ sisters married an instructor at the Carolo Wilhelmina Polytechnic Institute, who was a teacher of Peter von Voigtländer (1812-1878), who was then making photographic cameras and lenses. The Langenheim’s new brother-in-law sent them one of Voigtländer’s daguerreotype cameras and other apparatus, which made them decide to go into the photography business. William traveled to Germany in 1842 to arrange shipment of daguerreotype equipment and supplies, and to establish a distribution arrangement with Voigtländer. The 1843 Directory of Philadelphia listed, “W. & F. Langenheim - Daguerreotypers”. Ties between the lens manufacturer and the distributors were strengthened in 1845, when Peter von Voigtländer married the Langenheims’ younger sister.

The Langenheim business caused a big splash in 1845, with their production of “Panorama of the Falls of Niagara”. This was a series of five daguerreotypes, taken from the Canadian side by Frederick, and arranged to resemble a panoramic view from a balcony, with “columns” dividing the images (Figure 10). They sent copies to the US President, Queen Victoria, and other notables. That generated a lot of press, which brought in considerable business.

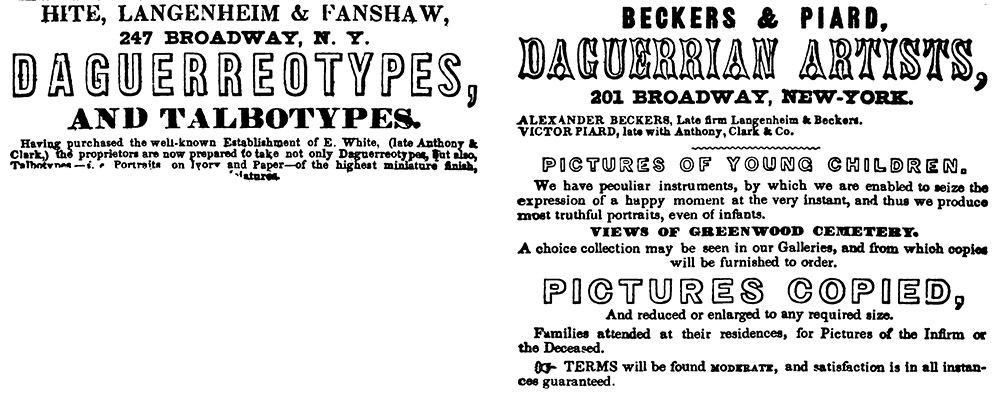

Also in 1845, the Langenheims formed a partnership with Alexander Beckers to operate a shop in New York City, as "Langenheim and Beckers". The partner left in 1849. The Langenheims then formed a partnership with George Hite and Thomas Fanshaw, which persisted in New York for another 2-3 years (Figure 12).

William temporarily left the businesses in 1846. The Republic of Texas gave land to him and other early volunteers who had fought for independence from Mexico. Despite being awarded over 2000 acres, William soon returned to Philadelphia due to epidemic yellow fever.

In March, 1847, William married Sophia Palmer, who was also an immigrant from Germany (Figure 13). They had three children, two of whom survived to adulthood, the other dying at 6 weeks old. Sophia died in December, 1852, at the age of 26, possibly due to post-partum infection. Frederick did not marry.

As the 1840s drew to a close, the popularity of daguerreotype photography was fading. In England, William Henry Fox Talbot developed a method that used paper for both the negative and the positive, which he called “talbotype”. The Langenheims negotiated with Fox Talbot for sole rights to distribute the talbotype process in the US, reportedly paying $6000. Unfortunately, the image quality of talbotypes was poor (compare the daguerreotypes in Figure 7 with the talbotypes in Figure 8). Frederick later said, “The best paper is always a fibrous substance, and the texture of the negative paper is always imprinted on the positive picture, and very few Talbotypes were fit to be shown, except after touching them up by hand. In portraits particularly this process is very apt to destroy the likeness”. The Langenheims made very little money from their talbotype distribution, forcing them to dissolve in early 1851 (Figure 16).

Nevertheless, Frederick exhibited in the 1851 International Exposition, London. He showed, “two large Talbotypes, one of which is a panoramic view of Philadelphia, executed in compartments, but wanting unity of effect. This artist, also, exhibits a series of subjects on glass, designated by him under the name of hyalotypes, being delicate miniatures, excellently adapted for magic-lanthorn subjects. The material would appear to be collodion, albumen, or some similar preparation, forming a film on the glass, capable of receiving the impression.”

Critic Robert Hunt, writing in The Art Journal, raved about Langenheim’s hyalotypes: “We are not made acquainted with the details of the process, but it appears evident that it is some modification of those processes on glass which we have already published-gelatine or albumen being made the surface on which the sensitive coating is spread. In the original French photographs on glass, the negatives only were received on that substance ... In the Hyalotype, both the positive and negative impressions are obtained on glass, and the result is as near an approach to perfection as we can imagine. The Hyalotype is the invention of Messrs. W. & F. Langenheim of Philadelphia … The most interesting application of this discovery is the construction of magic-lantern slides, taken from nature by the camera obscura, without the aid of the pencil or brush … We have now before us a series of these magic-lantern slides-the Hyalotypes-and we feel bound to declare that their delicacy and the perfection of the details cannot be overstated. In a view of Spring Garden Hall, Philadelphia, about three inches in diameter, the delineation of the details are marvellous, every stone in that fine building is distinctly marked, and the ornamental portions, the Corinthian capitals, the galleries of the tower, the delicate tracery around the clocks, given with such accuracy, that the more it is enlarged by lenses the more perfect and beautiful does it appear. The trees on one side of the building, the houses on the other, the rough hoarding in front, and all the rude evidences of yet incomplete masonic labours scattered around; and the lady with the parasol coming over the steps of Spring Hall are all equally perfect reflections of the scene. It is in every respect precisely the beautiful picture which would be seen when viewing such a spot in a very brilliant mirror. … The exquisite delicacy of the Hyalotype is, however, still more strikingly shown in copies of the engravings from the Vernon Gallery, which are now being published in the Art Journal. In these, not merely is the picture copied, but every line-the most delicate touch of the graver is retained—and when enlarged by a magnifying glass, it is seen that even the texture of the paper is preserved. Of the thousands of lines which cover our engraving of Collins's charming picture of the boy riding on a gate, not one is lost. The more we study the photographic picture, accustomed to every variety and having practised the art for years, familiar with its beauties and its wonders, we are astonished at the perfection of the details here preserved.”

In a later interview, Frederick said, “while in Paris in 1853, I was introduced to the celebrated optician, Dubosque-Soliel … they had come over to London to examine my transparent positive pictures taken on glass, and that since then, they had tried and made such transparent positive pictures on glass for the stereoscope.”

Frederick brought the technologies for glass stereoscopic photography home to Philadelphia, and the Langenheim brothers were back in business. The business included sales of series by subscription, described in The Photographic News, 1855: "Langenheim's New Series of American Stereoscopic Views -We, the undersigned, who by subscribing and furnishing F. Langenheim with the means to commence a new series of American stereoscopic views between Philadelphia and Niagara Falls, have received the number subscribed for, and take pleasure in expressing our entire satisfaction with them, and would recommend them to all who have a desire to cultivate a taste for their own American works of art and skill. They are also coloured with much taste and truthfulness to nature."

In addition, their “Stereoscope Cosmorama” catered to those who could not afford to purchase their pictures. It was described in May, 1855, as “views seen, magnified, through the stereoscope, now open to the public at Langenheim's Photographic Academy, No. 188, Chestnut street, opposite the Masonic Hall. The price of admission is 25 cents. Season tickets to July, one Dollar … The subjects now to be seen consist of a series of twenty-four Winter Views of the Falls of Niagara and Vicinity, which have never been exhibited in this or any other country; and of twenty-four views of the Principal Public Buildings and National Monuments in Paris and Vicinity. The views at present on exhibition will be changed at short intervals, so that on a subsequent visit to the Cosmorama the visitors will find a new and interesting series of views”.

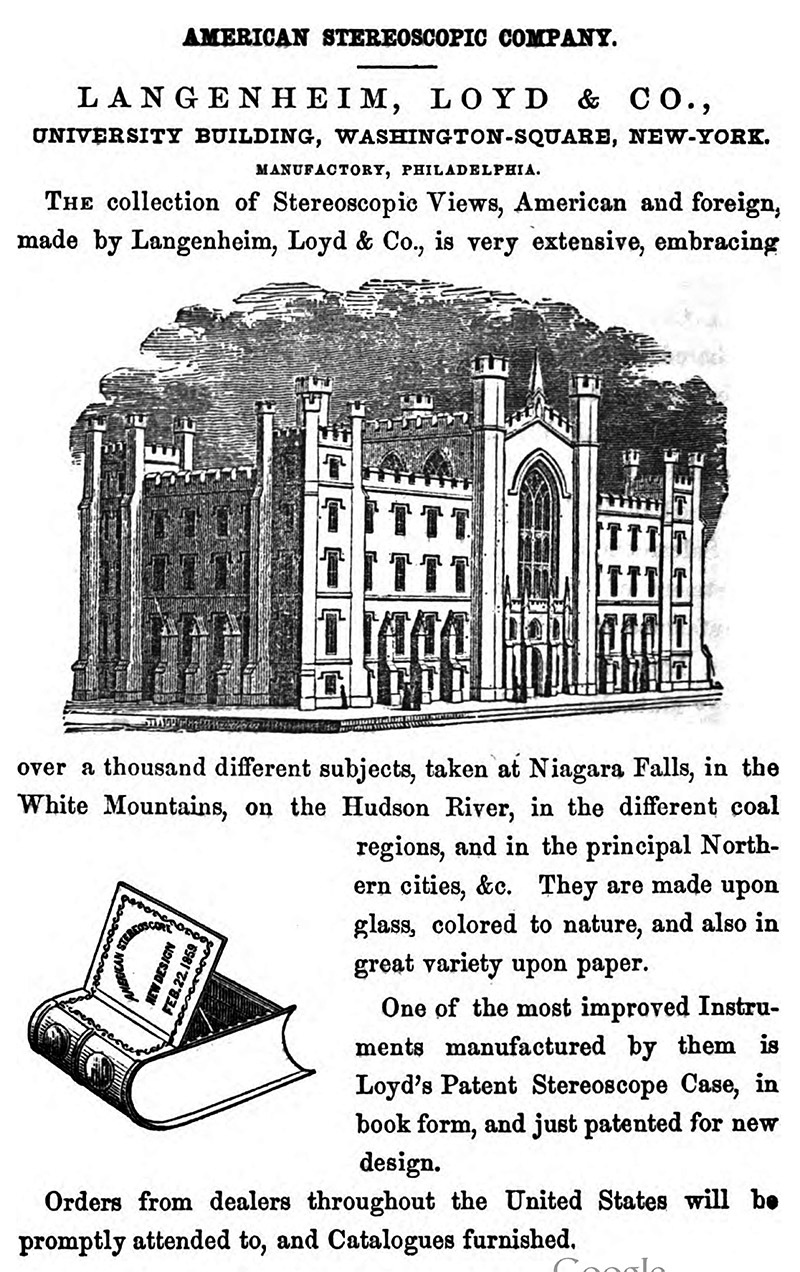

The Langenheims entered into a partnership with William Loyd to facilitate distribution of photographs by the Langenheim and stereoscopes that were made by Loyd. The 1855 article from The Photographic News that was quoted above continued, “These pictures are soon to be published upon glass and porcelain by an entirely new process. They are also to be published in a cheaper form upon albumenised paper, and may be had at the publication office of William Lloyd, 188, Chestnut Street, Philadelphia”. The partnership of Langenheim, Loyd & Co. was also known as The American Stereoscopic Company (Figure 5).

In England, photographer and microscope-manufacturer John B. Dancer had experimented with making microscopical photographs during the 1840s, but was stymied by the low resolution of the daguerreotype process. Likely inspired by the Langenheims’ hyalotype process, Dancer began producing high-resolution microphotographs by 1853.

An 1857 advertisement (Figure 5) shows the Langenheims selling, through their American Stereoscopic Company, “photographic microscopic pictures, embracing a number of portraits of distinguished persons and views of the most interesting American scenes”. Their production of American subjects was probably attractive to domestic customers, as opposed to the English scenes of Dancer and other British microphotographers.

The Boston Advertiser wrote, “The following delightful description of these unusual microscopic pictures was written by the editor of The Boston Advertiser, “Procure one of their microscopic photographs, and you will receive a piece of glass upon which you see a little circle about as big as a three-cent piece, in the centre of which are a few scratches not larger altogether than the head of a pin. Try to divine with your naked eye what these scratches are. Carry home the glass and ponder the question twenty-four hours. We did this, and were as wise on the subject the next morning as the day before. Get out microscope of some 400 magnifying power and the mystery vanishes. Those few scratches, not as big altogether as the head of a pin, are the whole Declaration of Independence – heading, body, and signatures, complete – 7000 and more letters, distinctly delineated on glass. You cannot see the first sign of a letter with the naked eye, but the microscope shows you that in this infinitesimal space the unerring instrument has faithfully copied the whole charter of the nation’s liberty, not distorting a hair’s-breadth of the least flourish of a signature. Is not this marvelous?” (quoted by Brey in “The Langenheims of Philadelphia”).

“Microscopic photographs” were still being advertised in 1871 (see Figure 6).

William Langenheim died on May 4, 1874. Frederick soon sold the business to Casper Briggs, then retired from work. Frederick died on January 10, 1879.

Figure 7.

Daguerreotype photographs of William (left) and Frederick (right). Adapted for educational, nonprofit purposes from metmuseum.org

Figure 8.

Talbotype photographs of William (left) and Frederick (right). In the talbotype process, both the negative and the positive are produced on paper. Due to fibers and other roughness of the paper, the negative lacks the clarity of what one can obtain on smooth metal or glass, and the paper of the positive compounds the flaws of the negative. The Langenheims paid a considerable sum for the rights to Talbot’s process, but were unable to recoup their expenses and were forced out of business in 1851. Their later development of transparent photography on glass allowed the brothers to re-start their business in 1855. Adapted for educational, nonprofit purposes from getty.edu

Figure 9.

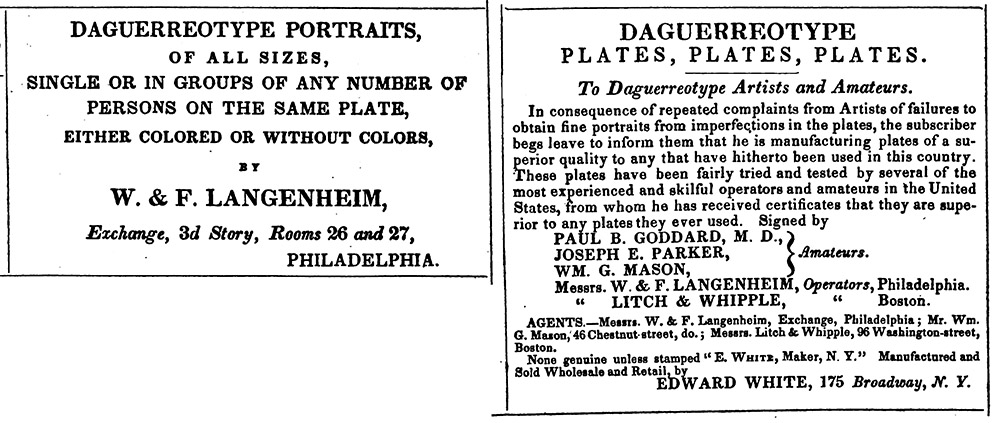

1845 advertisements for W. & F. Langenheim. From “Sheldon & Co.'s Business Or Advertising Directory”.

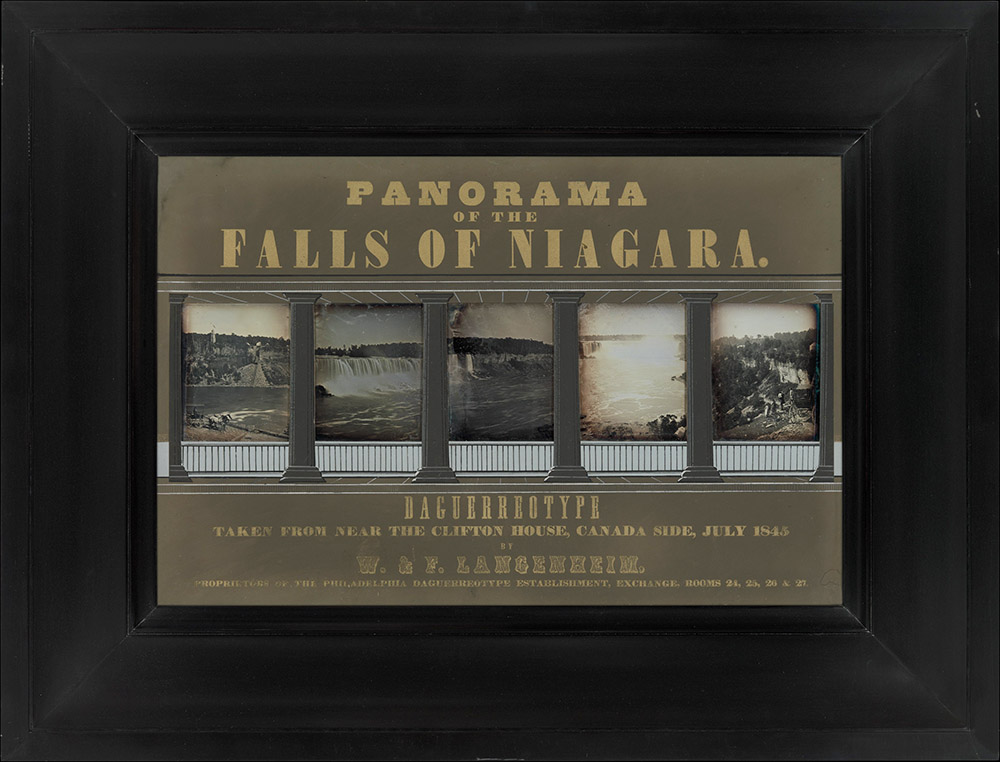

Figure 10.

Framed “Panorama of the Falls of Niagara”, a series of 5 daguerreotypes that were taken by Frederick Langenheim in 1845. The Langenheims sent copies to US President Polk, Queen Victoria, several German kings, Louis Daguerre, and others, which helped make the brothers famous. Adapted for educational, nonprofit use from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/286333

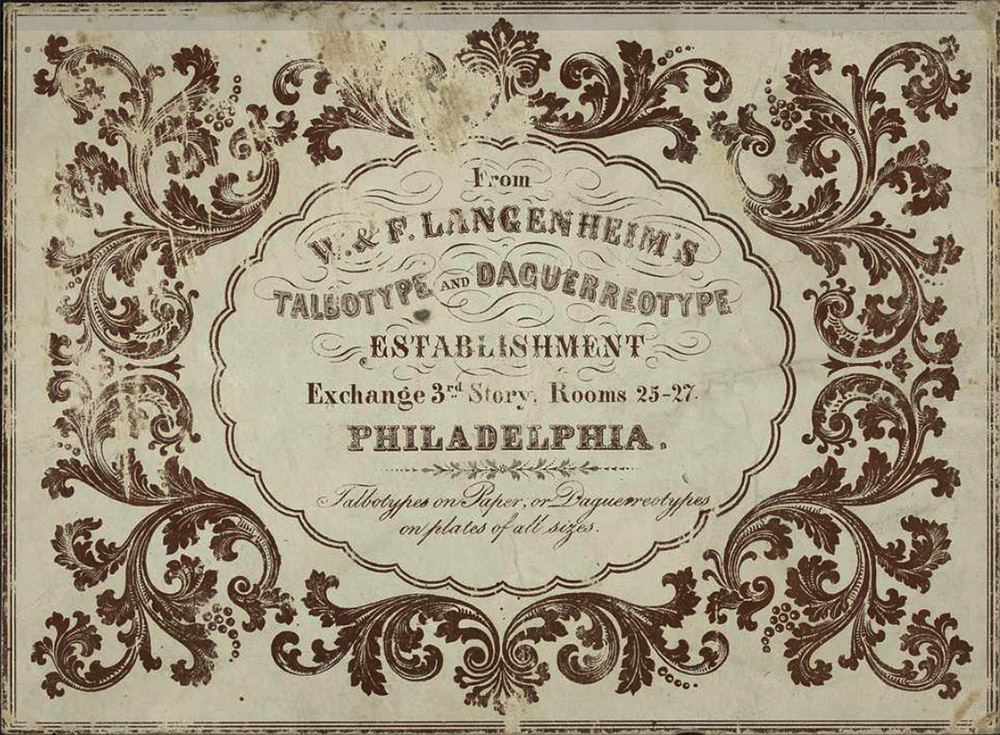

Figure 11.

ca. 1850 trade label of W. & F. Langenheim. Adapted for educational, nonprofit use from https://loc.getarchive.net/media/unidentified-man-half-length-portrait-w-and-f-langenheims-philadelphia-2

Figure 12.

1850 advertisements for the Langenheim’s New York partnership, and for their former partner, Alexander Beckers. From “New-York, Past, Present, and Future”.

Figure 13.

Daguerreotype photograph of William and Sophia Langenheim. They married in 1847, and Sophia died in 1852. Adapted for nonprofit, educational use from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/285769

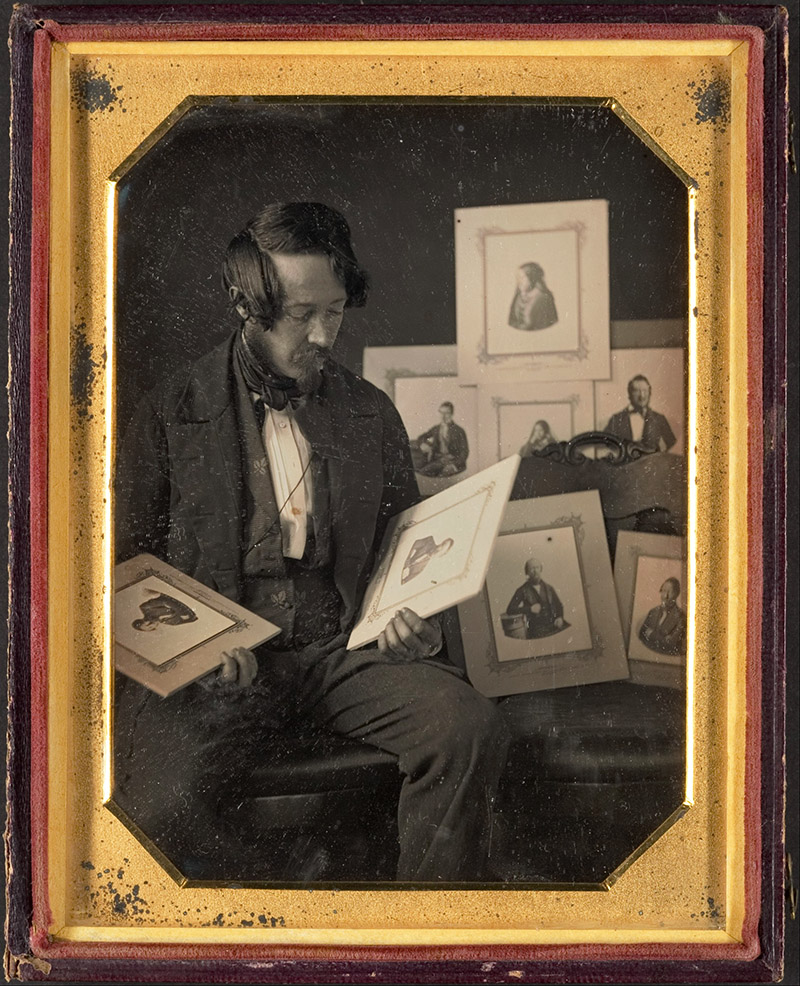

Figure 14.

A daguerreotype photograph of Frederick Langenheim examining talbotype photographs. These include images of William and himself (see Figure 8, above). Adapted for nonprofit, educational use from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/286315

Figure 15.

Circa 1849-1850 hyalotype lantern slide of the Smithsonian Institute’s “Castle” under construction, by W. & F. Langenheim. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://siarchives.si.edu/blog/deconstructing-mystery-rare-photo-proves-be-earliest-ever-taken-smithsonian-castle

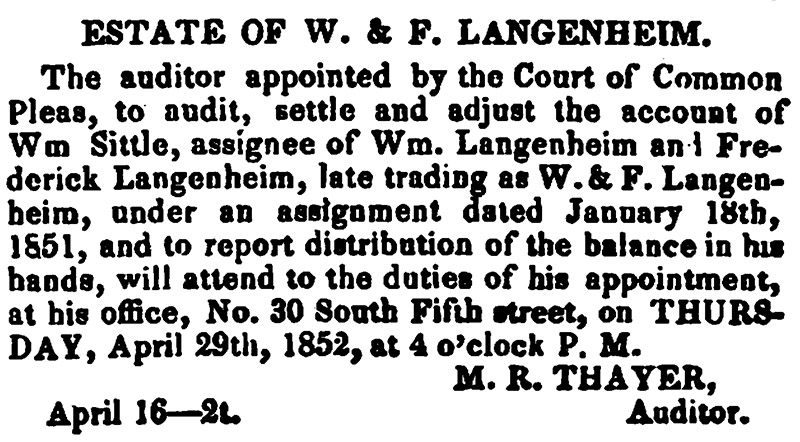

Figure 16.

Figure 16. W. & F. Langenheim was bankrupted in 1851, primarily due to lack of success in distributing the talbotype method. From “Legal Intelligencer”, April 16, 1852.

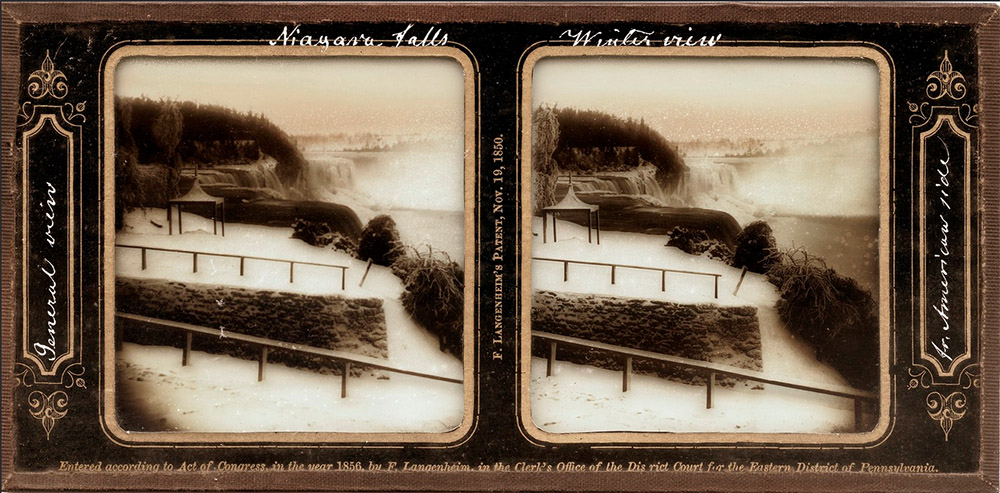

Figure 17.

Circa 1855 glass stereoview by F. Langenheim. “A series of twenty-four Winter Views of the Falls of Niagara and Vicinity” was displayed in May, 1855 the Langenheim’s “Stereoscope Cosmorama”, so this stereoview probably dates from around that time. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an unattributed image found on the internet.

Figure 18.

Figure 18. 1859 advertisement from Langenheim, Loyd & Company / American Stereoscopic Company. From “The New-York Sketch Book”.

Figure 19.

1873 advertisement from W. & F. Langenheim. From “Photographic Mosaics”.

Resources

Arrival record of Wilhelm Langenheim (1834) Port of Baltimore, accessed through ancestry.com

Beckers, Alexander (1889) Fifteen years’ experience of a daguerreotyper, The Photographic Times, Vol. 19, pages 131-132

Bizarre (1855) Stereoscope Cosmorama, page 253

Bracegirdle, Brian (1998) Microscopical Mounts and Mounters, Quekett Microscopical Club, London, page 61

Brey, William (1979) The Langenheims of Philadelphia, Stereo World, Vol. 6, pages 4-20

Discharge record of William Langenheim (1840) accessed through ancestry.com

Doggett's New York City Directory (1845) “Langenheim, F. daguerreotype, room 201 Broadway. Langenheim & Becker, daguerreotype, 201 Broadway”, page 212

Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, 1851: Reports by the Juries (1851) Langenheim, page 277

Gobright, John C. (1859) New-York Sketch Book, Advertisement from American Stereoscopic Company in back

Langenheim, Frederick (1854) Letter, Photographic and Arts Journal, October issue, page 320

Hull, Robert (1851) On the application of science to the fine and useful arts, The Art Journal, pages 106-107

Legal Intelligencer (1852) Estate of W. & F. Langenheim, April 16, page 1

New-York, Past, Present, and Future (1850) Advertisement from Hite, Langenheim & Fanshaw, page 34

Photographic and Arts Journal (1854) Note on visit from Frederick Langenheim, September issue, page 288

Photographic and Arts Journal (1854) Note on Frederick Langenheim, October issue, page 320

Photographic Mosaics (1871) Advertisement from W. & F. Langenheim, page 178

Photographic Mosaics (1873) Advertisement from American Stereopticon Comapany, page 163

Sachse, Julius (1855) Philadelphia’s share in the development of photography, The Photographic News, pages 356-357

Simons, M.P. 1857) Plain Instructions for Colouring Photographs in Water Colours and India Ink, advertisement from American Stereoscopic Company in back

Sheldon & Co.'s Business or Advertising Directory (1845) Advertisements from W. & F. Langenheim, pages 15 and 43

Texas History Trust (accessed June, 2023) https://www.texashistorytrust.org/source-material-texas-history/muster-rolls

U.S. census and other records, accessed through ancestry.com