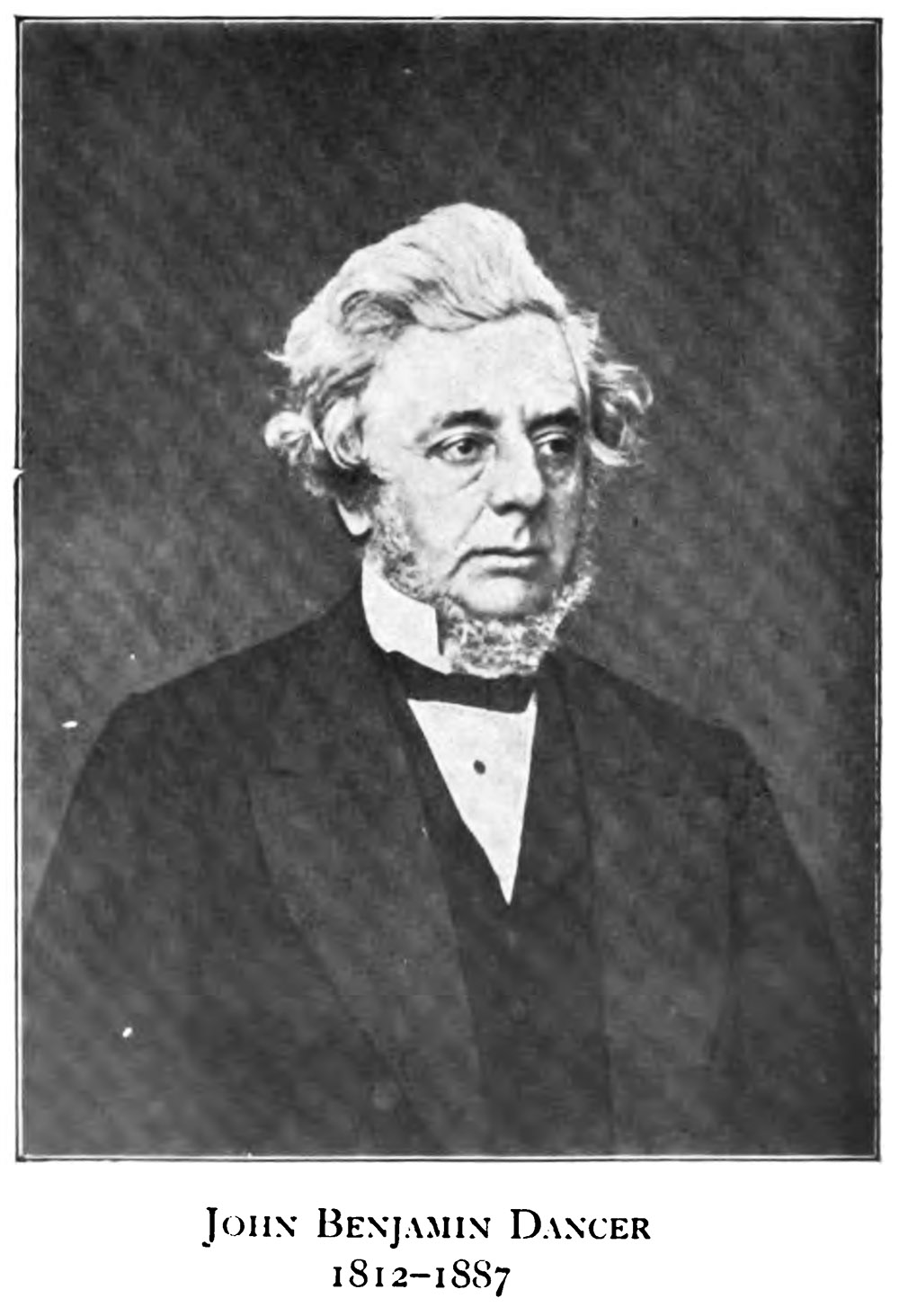

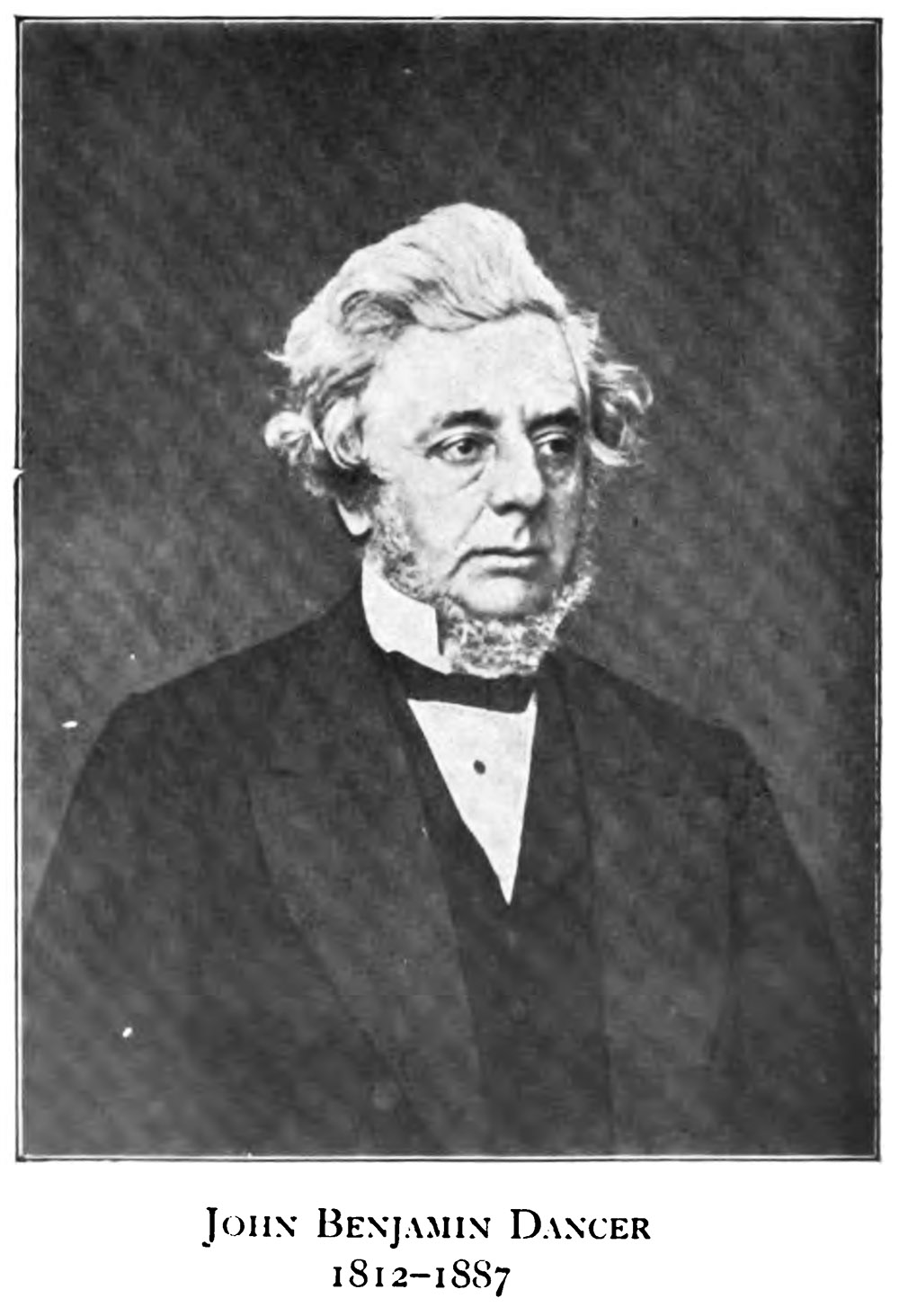

John Benjamin Dancer, 1812 - 1887

Josiah William Dancer, 1837 - 1907

Elizabeth Eleanor Dancer, 1846 - 1925

Anna Maria Dancer, 1847 - 1896

by Brian Stevenson

last updated February, 2025

J.B. Dancer is best known to modern microscopists for his microphotograph slides (Figures 2-7). He is generally credited as being the inventor of those novelties, which used a camera and a reversed microscope to reduce, rather than enlarge, the image.

Joseph Sidebotham wrote in 1859, "Mr. Dancer, if not actually the first, was one of the first who took a daguerreotype picture in this country, before any specimens taken by Daguerre himself had been brought over: as early as the year 1839 he paid some attention to the production of minute photographs on silver plates, reducing a bill of twenty inches in length to one-eighth of an inch, by means of an achromatic combination of one and-a-half inch focus. … I have in my possession two micro-photographs, given to me by Mr. Dancer early in 1853; they are about one-sixteenth of an inch in diameter. One is a copy of the monumental tablet erected to the memory of Sturgeon, the electrician; the other a group of portraits of Mr. Dancer’s own family. Since that time Mr. Dancer has paid considerable attention to the subject, and produced much more minute and perfect specimens, copies from pictures and photographs from nature in great variety, and has supplied them to the principal opticians here and on the continent, and there are few interested in such matters who do not possess some of them. The Queen is in possession of a set of portraits of members of the royal family and other subjects, the production of our respected townsman". The 1853 microphotographs described by Sidebotham are reproduced below in Figures 2 and 4.

Dancer also sold a wide variety of other types of microscope slides, prepared by his business or brought in from other slide-makers (Figures 8-12).

J.B. Dancer was also a skilled manufacturer of microscopes and other optical / technical instruments. He learned from his father, Josiah Dancer, a skilled optician and machinist. John took over his father’s business in Liverpool after the elder man’s death in 1835. In 1841, Dancer formed a partnership with optical and scientific instrument-maker Abraham Abraham, and opened a branch store in Manchester as “Abraham and Dancer”. When the partnership dissolved in 1844, Dancer continued the Manchester shop under his own name.

Of J.B. Dancer’s microscopes, an obituary wrote, “When Mr. Dancer established himself as an optician in Manchester his presence soon made itself felt amongst the few microscopists then living in the district. Good microscopes were then costly, and worthless ones very common. Mr. Dancer successively brought out several forms of instruments, as excellent in their mechanical and optical arrangements as they were moderate in price. Instruments fully equal to the requirements of original research were thus brought within the reach of many whose observing faculties were more conspicuous than their financial resources. It would be difficult to over-estimate the stimulus which Mr. Dancer thus gave to Manchester microscopy; it cannot be doubted that the present energy of our local microscopists is the direct outcome of the impulse which their means of research then received".

William B. Carpenter wrote this testimonial to Dancer on November 30, 1846: "I have great pleasure in stating that, having examined with much attention the Achromatic Microscope recently constructed by Mr. Dancer of Manchester I can speak most favourably of its performance, both mechanically and optically. The adjustments are effected with the greatest ease and precision; and the Achromatic objectives are much superior to those usually supplied with instruments of so low a price. Altogether I have no hesitation in saying, that I have seen no instruments which I can so strongly recommend to those who desire to possess an Achromatic Microscope for general use, but who are obliged to limit themselves to the very moderate price, from 9 to 12 guineas according to the number of powers, for which Mr. Dancer furnishes the one alluded to".

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Two ca. 1851 self-portrait stereoviews of J.B. Dancer, surrounded by optical, scientific, and engineering apparatus that he manufactured and/or sold. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://www.gallery.ca/collection/artwork/self-portrait-with-scientific-apparatus and http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O119158/scientist-in-his-laboratory-daguerreotype-dancer-john-benjamin/

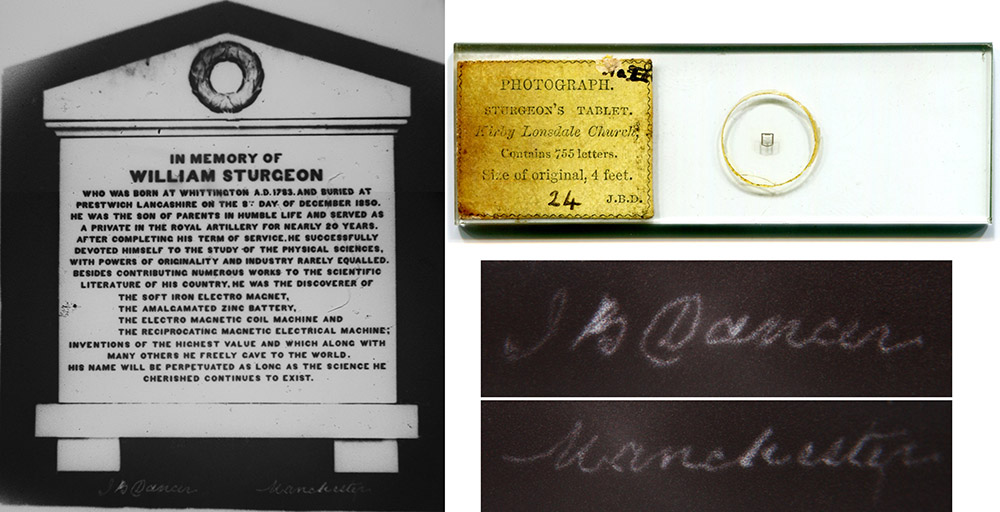

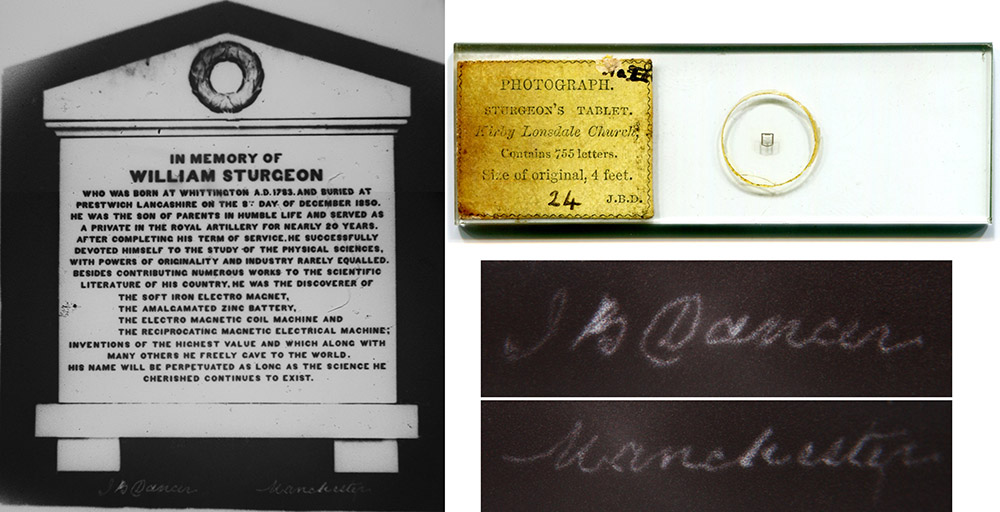

Figure 2.

J.B. Dancer's first commercial microphotograph, of the memorial tablet of William Sturgeon. Joseph Sidebotham reported that he received one of these microphotographs in 1853. The slide may be found either with a small number 1 in the lower left corner of the label, or without a number (as here). Dancer's unnumbered slides are presumed to be fairly early productions, when a limited number of different images were available from him. The label notes that the original image is 4 feet wide, and so was likely chosen as a subject to emphasize Dancer's extensive miniaturization to reduce it to less than 2 mm. Dancer signed this, and many other microphotograph negatives, with his name and "Manchester". It is not uncommon to find microphotographs with other retailer's labels but with Dancer's signature in the image, indicating that he was the actual source.

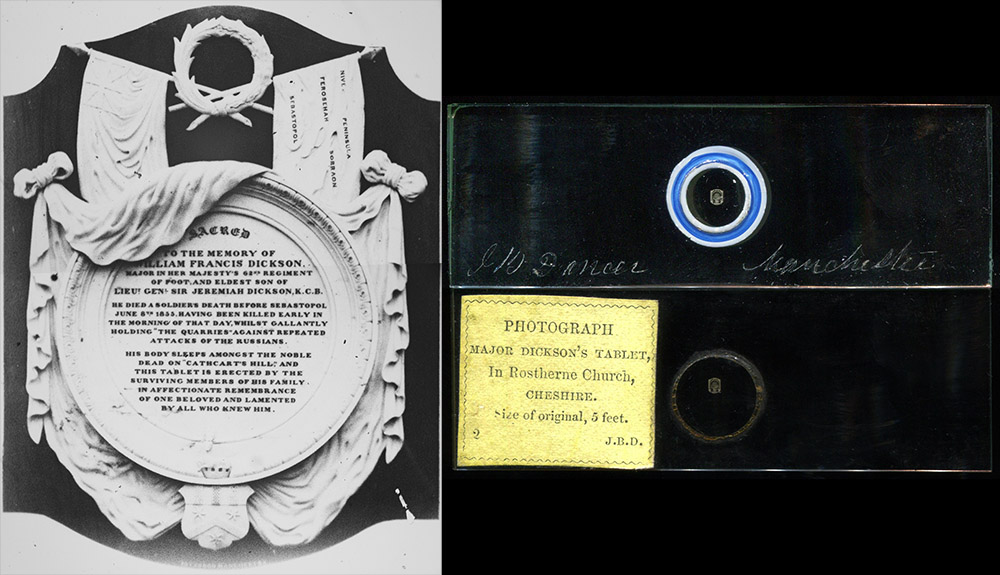

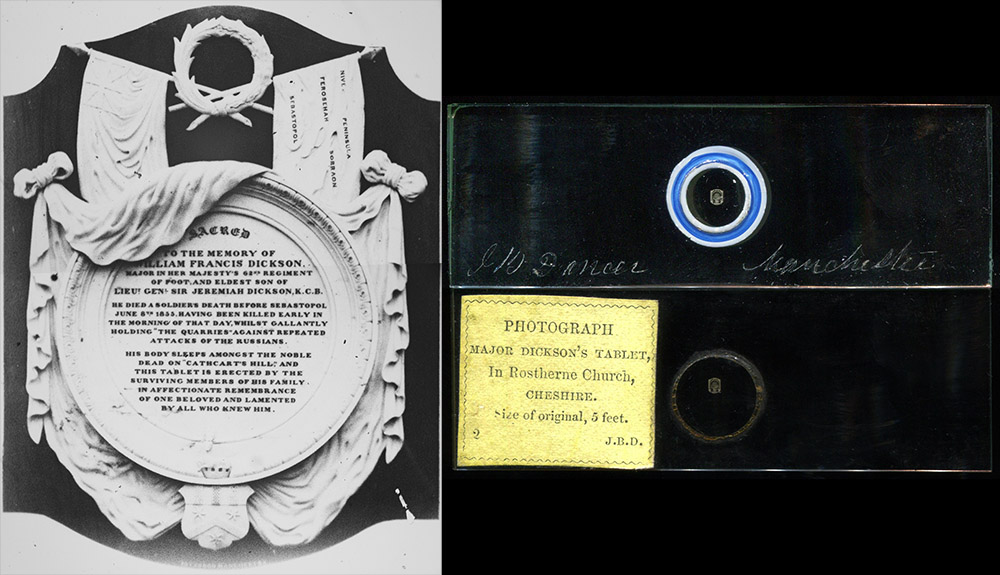

Figure 3.

Two examples of Dancer's second commercial microphotograph, of the memorial tablet of Major W.F. Dickson. The original is 5 feet tall, again emphasizing Dancer's feat of miniaturization. The top slide was probably a very early production, with a diamond-engraved description and lacking a paper label. Dancer is not known to have used ringing on his microphotograph slides, so the colored ringing on this example was probably applied by an owner.

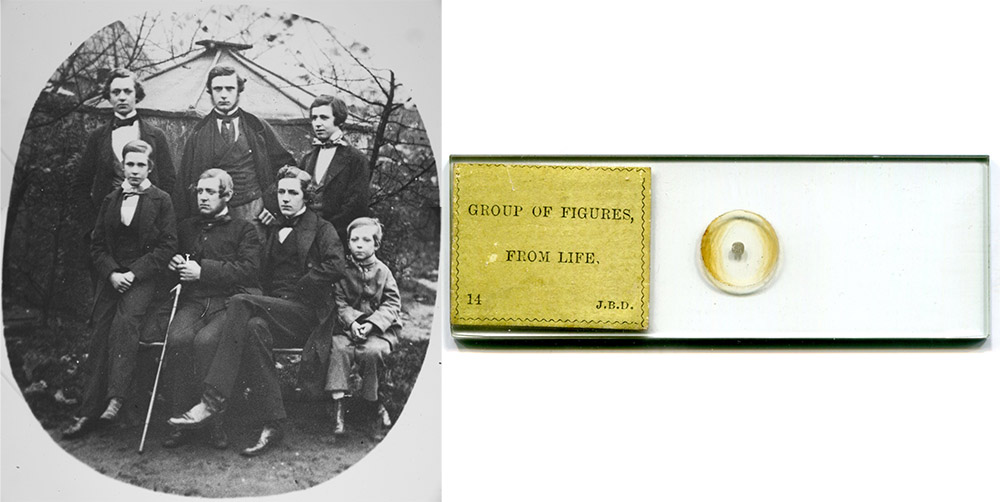

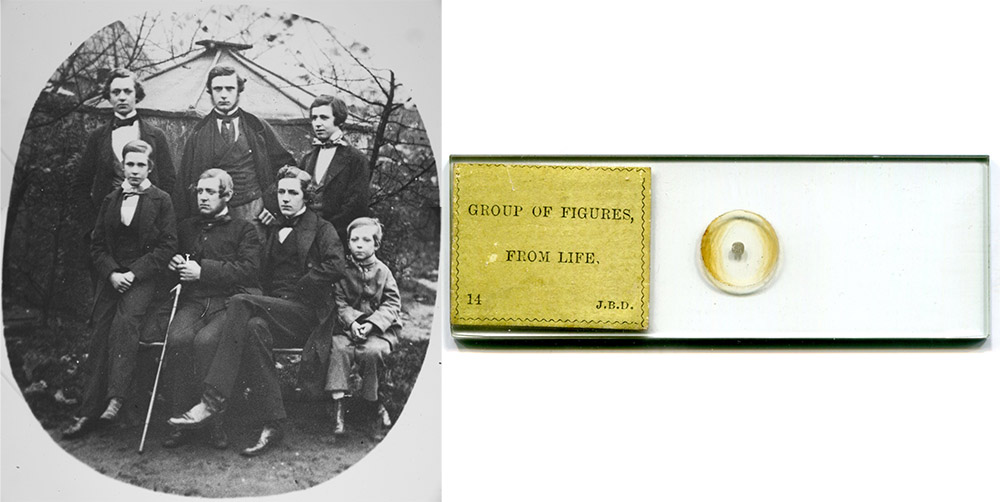

Figure 4.

Three label variants of Dancer's third commercial microphotograph. Dancer produced slides with different numbering schemes at different times, as illustrated by the lower slide with number "22". This microphotograph featured members of Dancer's family, photographed in 1853 (possibly earlier): wife Elizabeth (1819-1889) with four sons and two daughters. The girls are Elizabeth (1846-1925) and Anna (1847-1896). The young boy in skirts on his mother's right was probably James (1844-1889), who would have been around 9 years old. The youngest of the five sons, Charles (1850-1939), was only 2-3 years old. The other boys are the Dancers' elder sons: Josiah (1837-1907), John (1839-1876), and William (1841-1928).

Figure 5.

Microphotograph 14 features J.B. Dancer (center, with a walking stick), the five Dancer sons, and another, unknown man.

Figure 6.

A rare Dancer microphotograph, unnumbered and not recorded in any known list. The five Dancer sons are shown, with youngest son Charles still in skirts, suggesting that it was taken during the late 1850s (Charles was born in 1850). The three middle boys, John, William, and James, are wearing some sort of uniform. The photographs shown in Figures 4, 5, and 6 were all taken in the same location, in front of a building with an angled roof, possibly the garden of the Dancer home in Crumpsall, Lancashire. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

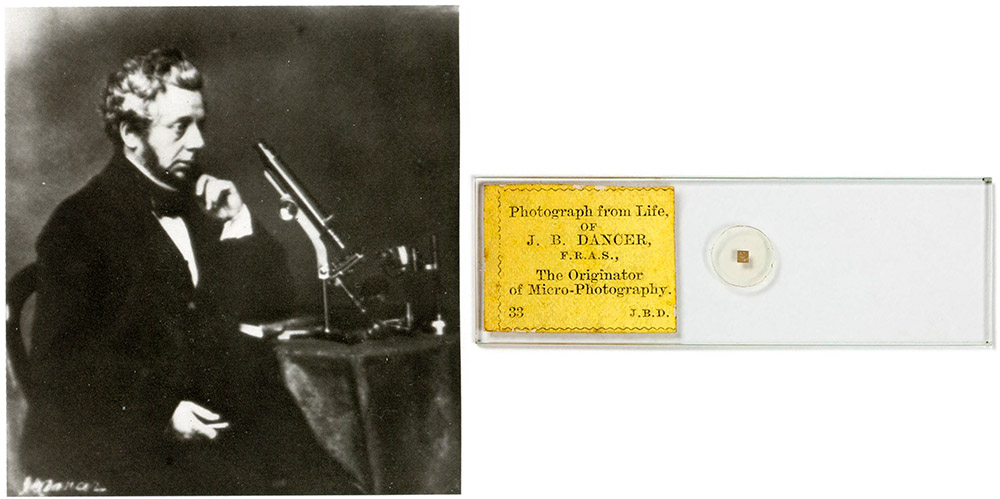

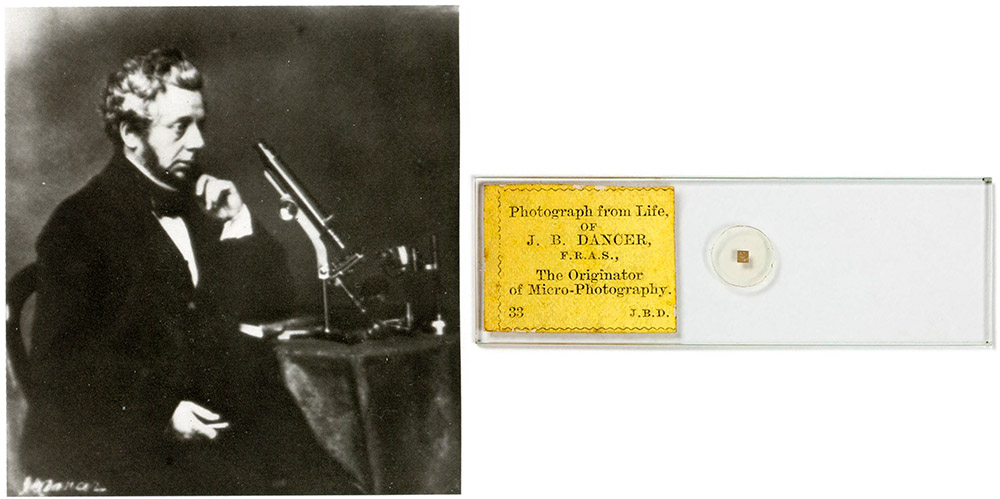

Figure 7A.

Dancer microphotograph 33, a self portrait, circa 1860. The microscope appears to be the same model shown in Figure 21, below. Dancer was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society (F.R.A.S.) on March 9, 1855. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from Bracegirdle and McCormick, and https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co8405564/microphotograph-photograph-from-life-of-j-b-dancer-microphotograph

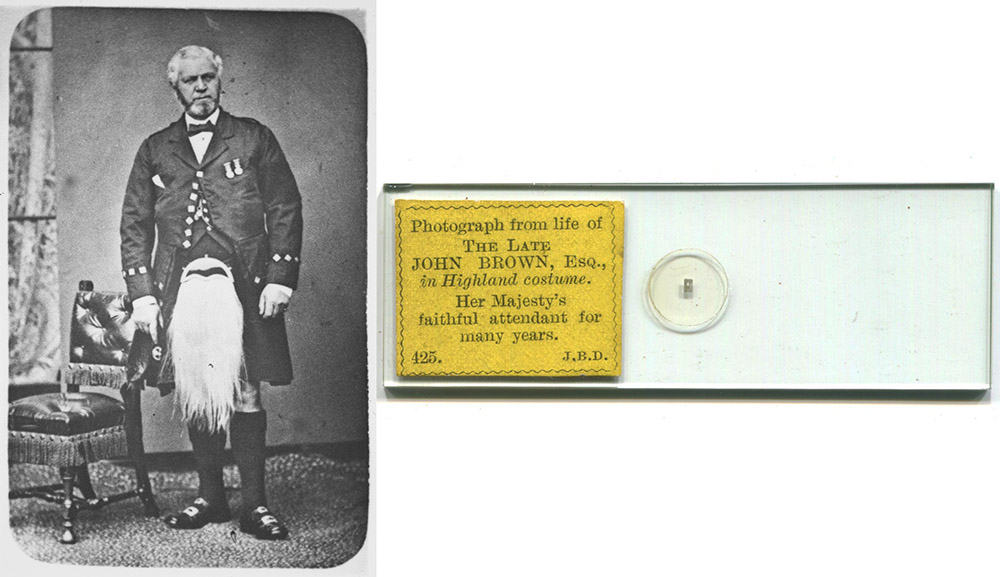

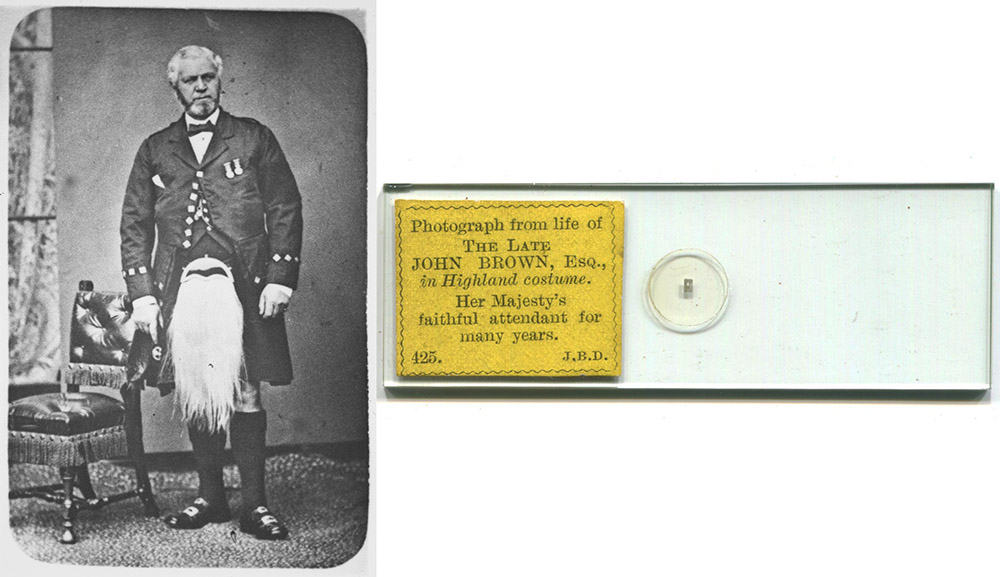

Figure 7B.

Although Bracegirdle and McCormick's "The Microscopic Photographs of J.B. Dancer" illustrates the majority of Dancer's microphotoraphs, those authors were not able to locate examples of all known slides. Examples of many of those "unknown" microphotographs do exist, however, such as this microphotograph number 425, "The Late John Brown", which was in another collection at the time that the Dancer book was written.

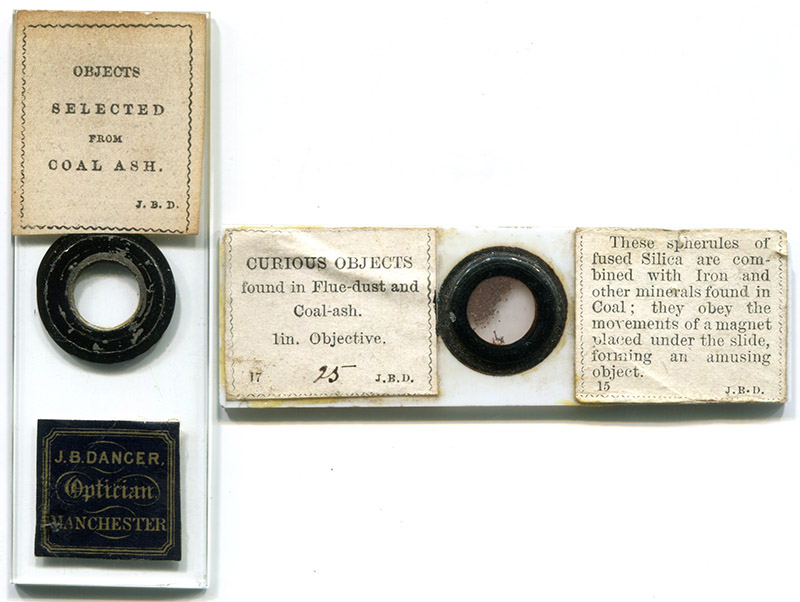

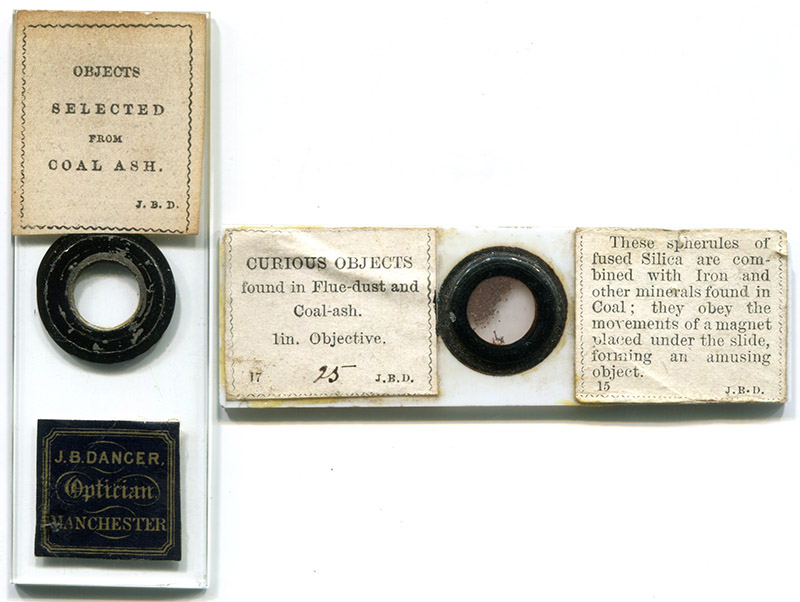

Figure 8.

"Curious objects found in flue-dust and coal-ash". Dancer wrote on "Microscopical examination of coal ash from the flue of a furnace" in 1868. The editor of "Microscopical News and Northern Microscopist" wrote in 1882 that Dancer had "not long since … kindly sent us a slide of these particles".

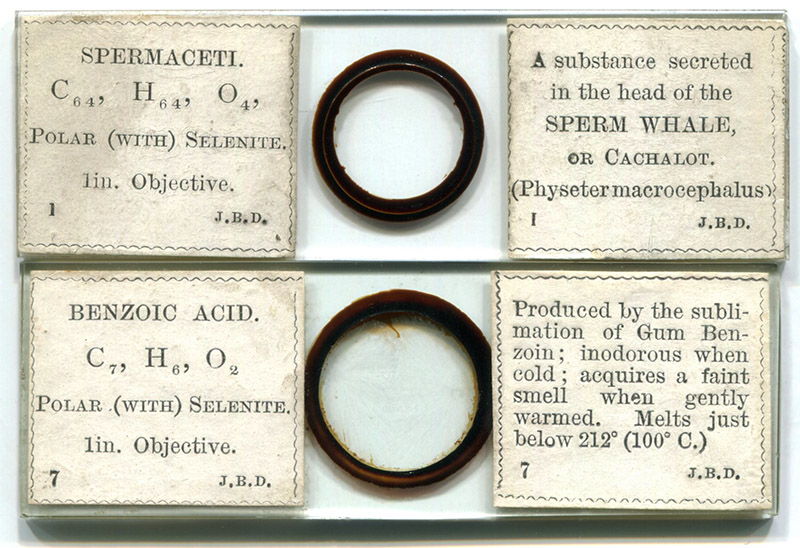

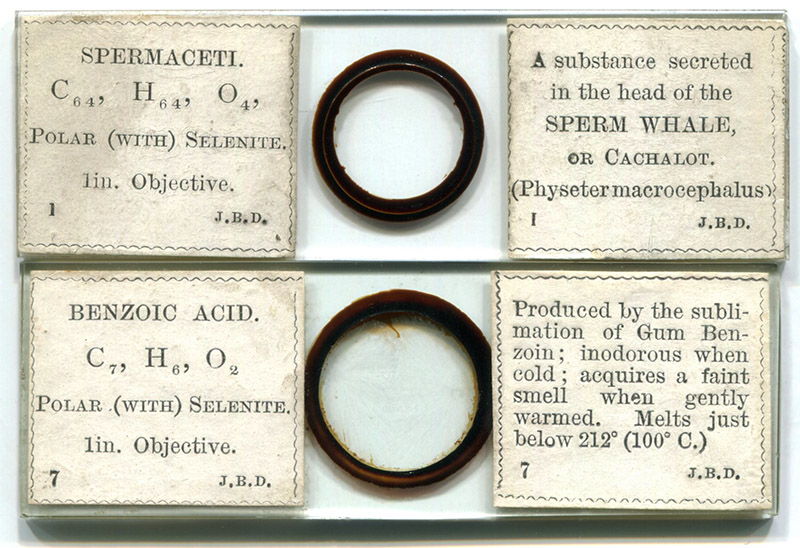

Figure 9.

Dancer produced a series of about 20 slides of chemicals, for microscopic observations between crossed polarizing filters. These may date from about 1870: on January 3 of that year, "Mr. J.B. Dancer, F.R.A.S., presented the (Microscopical and Natural History Section of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society) with a box containing twelve new polarizing objects. These partly consisted of some of the hard fatty acids which form very effective objects, and partly of crystallizations of some of the hydro-carbon compounds which compete with the best specimens of polarizing objects of the present day".

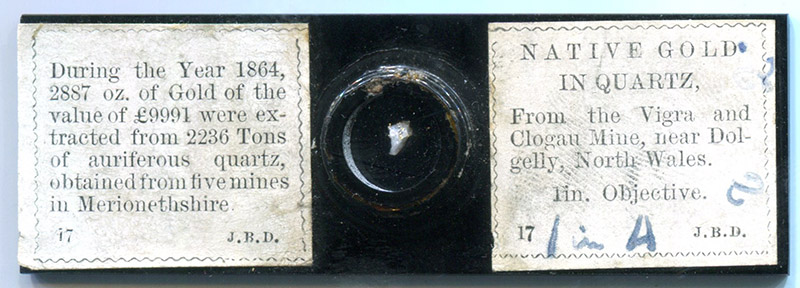

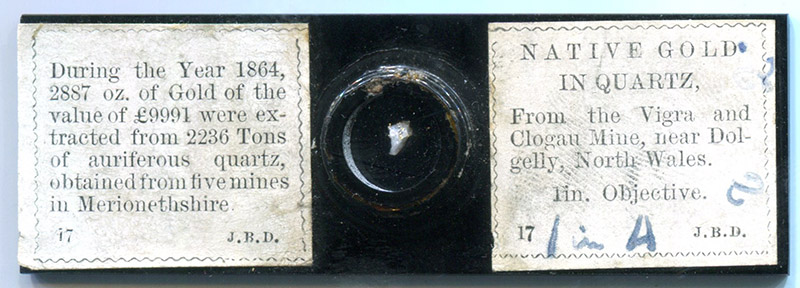

Figure 10.

"Native gold in quartz from the Vigra and Clogau Mine, near Dolgelly, North Wales", dry-mount on black opaque glass. Dancer's label states the value of gold mined from Merionethshire in 1864, suggesting that this slide was produced shortly after that year.

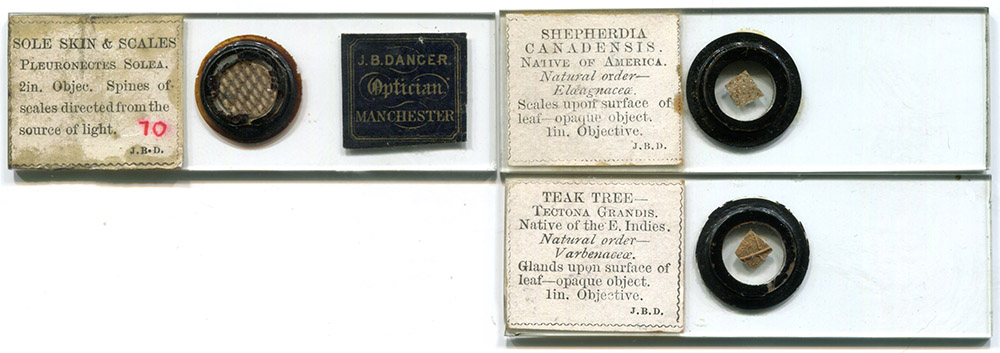

Figure 11.

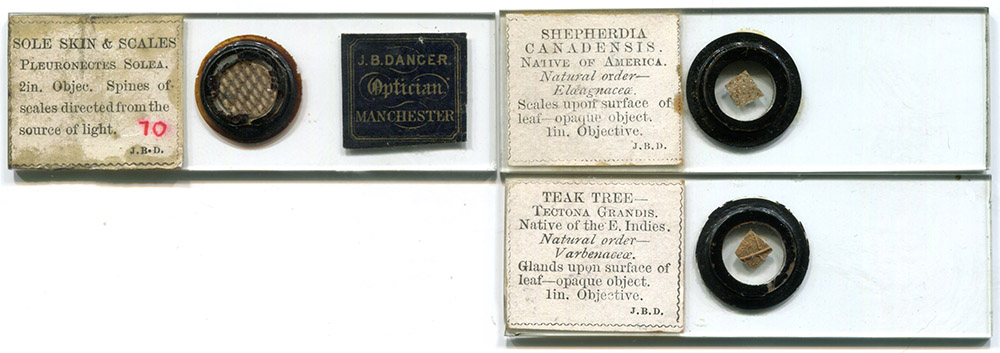

Dry-mounts of scales on a fish skin, and leaves from three species of foreign trees.

Figure 12.

Microscope slides from other makers that were retailed/re-sold by J.B. Dancer. Top row, left to right: Charles M. Topping, John T. Norman, J. & T. Jones, an unidentified amateur, and two slides by Joseph Bourgogne (top slide sold by Dancer, the lower slide sold by Abraham & Dancer). Bottom row, a stage micrometer, which may have been produced by Dancer, mounted in a 4 mm (approximately 5/32 inch) thick wooden block.

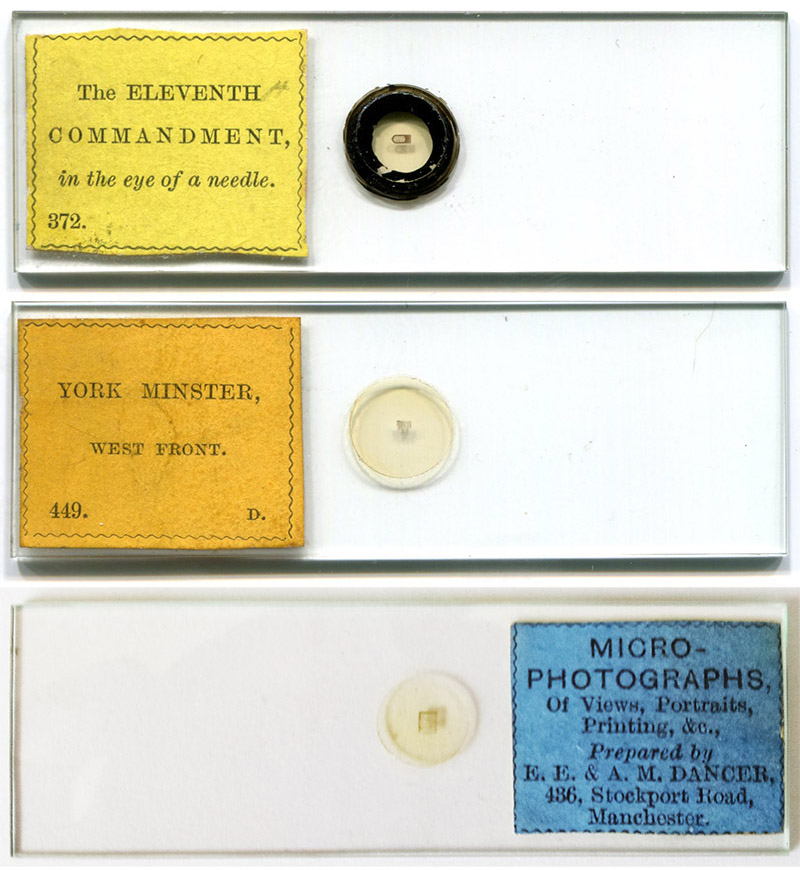

Figure 13.

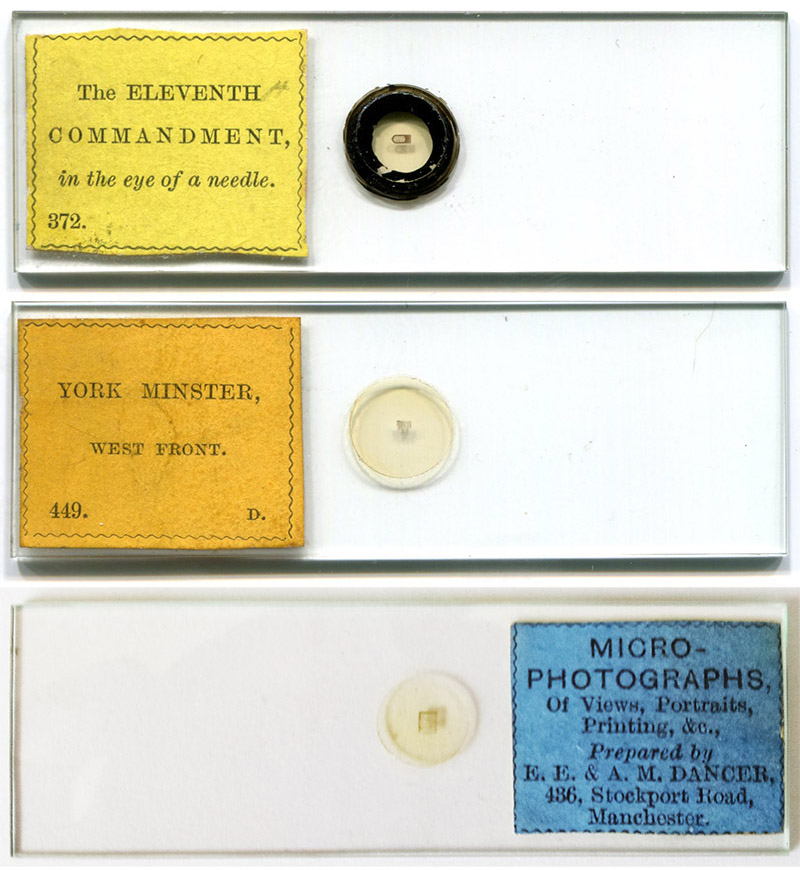

(Top to bottom) High-numbered Dancer microphotographs without J.B.D.'s initials, with only a "D", and labeled with Elizabeth and Anna Dancer's names. J.B. Dancer's sight began to fail in 1870, and he was essentially blind by 1878. His elder daughters continued his microphotograph business from a shop on Stockport Road (see Figure 14). The 1881 census listed both Elizabeth and Anna as working as "photographers", and letters written in 1883 by artist James Nasmyth to J.B. Dancer complimented Elizabeth and Anna Dancer on the microphotographs that they had produced. The top slide, "The Eleventh Commandment" was advertised by the Dancer daughters in 1884 (see Figure 14).

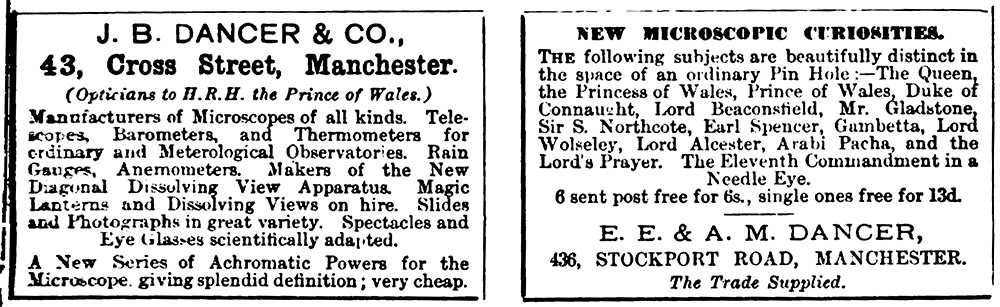

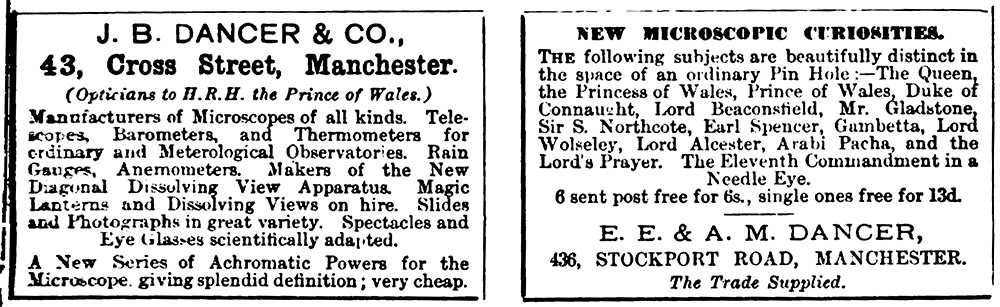

Figure 14.

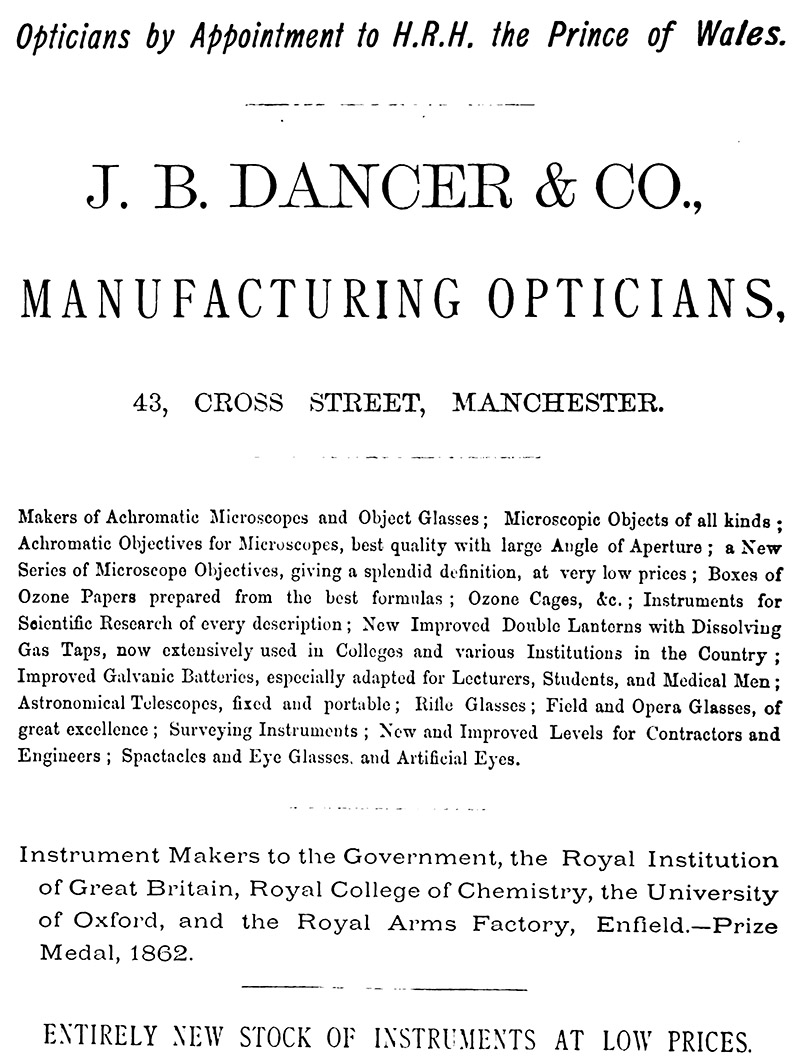

Two side-by-side 1884 advertisements. J.B. Dancer had been blind and unable to work since 1878. The "J.B. Dancer & Co." business at 43 Cross Street was probably operated by his eldest son, Josiah, and possibly others. That business ended in 1884. Microphotographs, old and new, continued to be produced by his elder daughters Elizabeth and Anna, who operated from a separate shop. The advertised microphotographs include Dancer 363 through 372, confirming that those were produced by the Dancer daughters. From "The Microscopical News and Northern Microscopist".

Figure 15.

Microscope slides that were not made by J.B. Dancer. Brian Bracegirdle’s Microscopical Mounts and Mounters includes images of slides that were stated to have been prepared by J.B. Dancer, apparently due to the slide’s labels having a monogram with the letters “J”, “B”, and “D” (Plates 14-F and 43-G). All bear dates from the early- to mid-1870s, which Bracegirdle referred to as "standard" slides from Dancer’s “main period”. However, Dancer was diagnosed with diabetes in 1870, had three operations for glaucoma, and was too blind to work by 1878. Moreover, these monogrammed, handwritten slide labels are not “typical” of Dancer’s productions - his slides generally have typeset labels (see Figures 2-11). Instead, the monogram and period of activity point to the maker having been Benjamin Daydon Jackson (1846-1927), who joined the Linnean Society of London in 1868, the Quekett Microscopical Club in 1869, and the Royal Microscopical Society in 1872. He was a frequent exhibitor of slides at meetings of the QMC, with the vast majority of his preparations being of botanical specimens.

Figure 16.

Also not made by J.B. Dancer: a Micrograph set, with turned ivory viewer and circular glass microphotographs. Although Bracegirdle and McCormick (1993) attributed these instruments to J.B. Dancer, they did not provide any evidence. Extensive investigations by Stanley Warren (2014) conclusively determined that Dancer could not have been the maker of the Micrograph, but instead identified John C. Stovin (1814-1896) as the maker. Stovin was a major maker of microphotograph slides, identified by his initials "J.S." or "J.C.S.". Accompanying instructions accompanying Micrographs state that these devices were "exhibited at the International Exhibition 1862 Class 14", where Stovin exhibited and earned praise for his microphotographs. 73 of the microphotographs known to accompany Micrograph sets were also produced as 1x3 slides by Stovin, while only 13 of them match Dancer productions (all of the Dancer matches are common pictures that were produced by numerous microphotographers).

Figure 17.

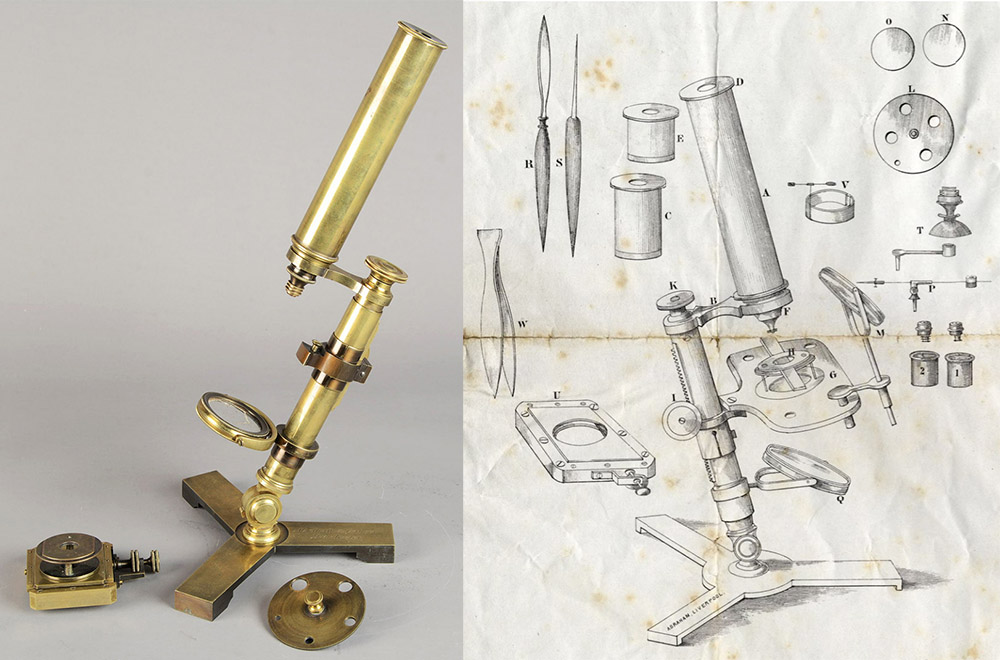

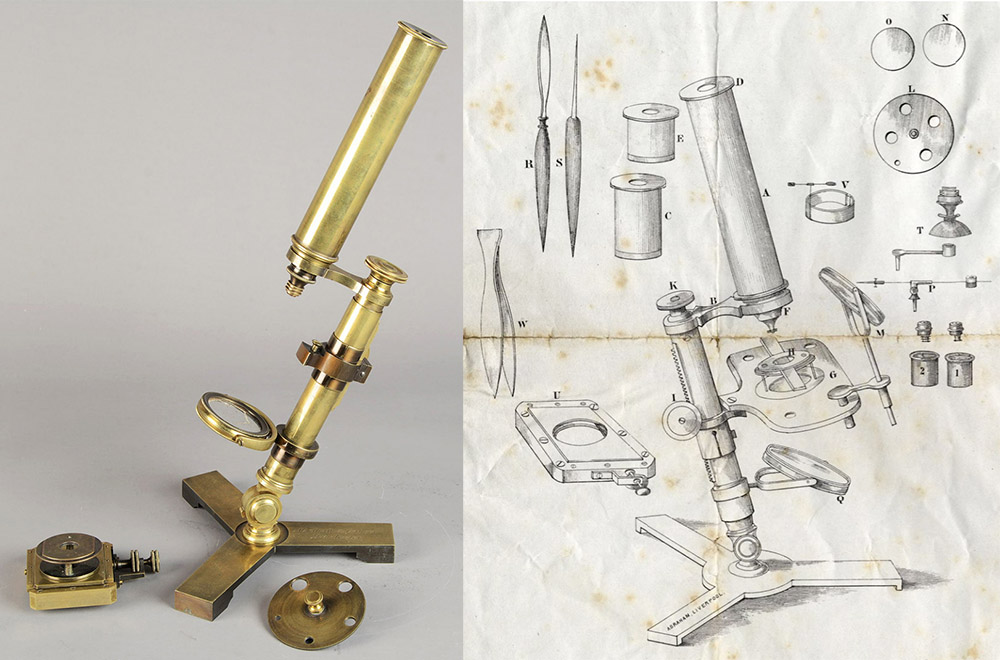

Microscope retailed by Abraham and Dancer, 1841-1844. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from The Museum for the History of Science.

Figure 18.

(Left) Another microscope signed “Abraham and Dancer”, and therefore ca. 1841-1844. Other examples of this model are known that are signed by only Abraham. (Right) Illustration from "Directions for using the compound achromatic microscope manufactured by A. Abraham, 20, Lord Street, Liverpool, and Abraham and Dancer, 13, Cross Street, King Street, Manchester". Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://diglib.amphilsoc.org/islandora/object/text%3A661#page/1/mode/1up .

Figure 19.

An 1841 Advertisement for achromatic microscopes, by Abraham & Dancer (Manchester) Abraham Abraham (Liverpool), and Abraham & Co. (another of Abraham’s partnerships, located in Glasgow). From "The Athenaeum".

Figure 20.

Dancer’s initial shop in Manchester was located at 13 Cross Street, as was also the Abraham and Dancer shop. This early Dancer microscope bears a trade label from that location.

Figure 21.

Another early Dancer microscope from his 13 Cross Street shop. This was designed for microscopical examination of cloth, an important manufactured product of Manchester. Adapted with permission from https://microscope-antiques.com/dancercloth.html .

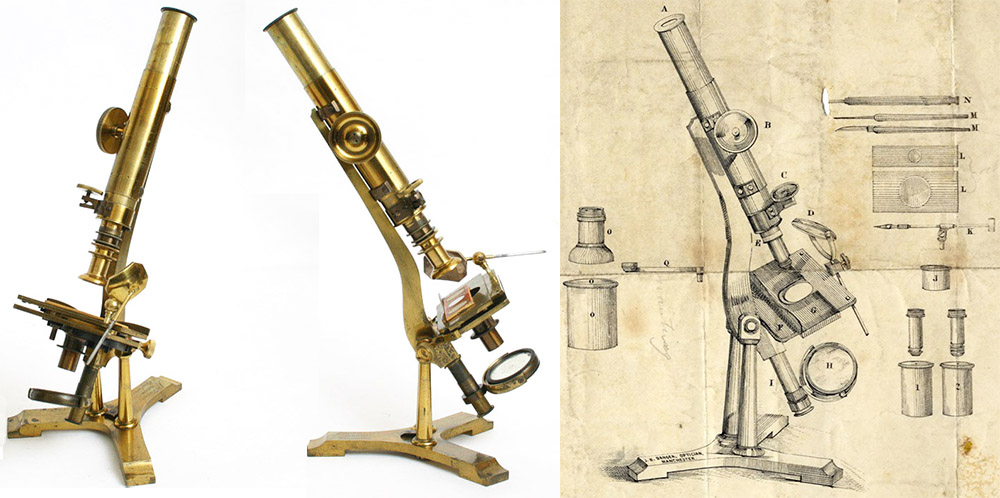

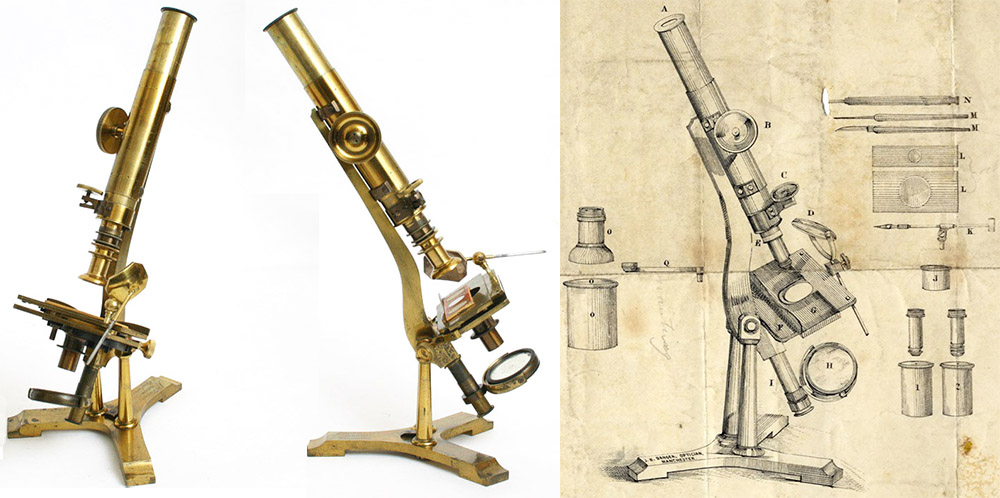

Figure 22.

The illustration bears Dancer’s address of 13 Cross Street, Manchester, dating this microscope to between 1845 and 1848, when Dancer moved to 43 Cross Street. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site and https://diglib.amphilsoc.org/islandora/object/description-achromatic-microscope-made-j-b-dancer-optician-13-cross-street#page/1/mode/1up .

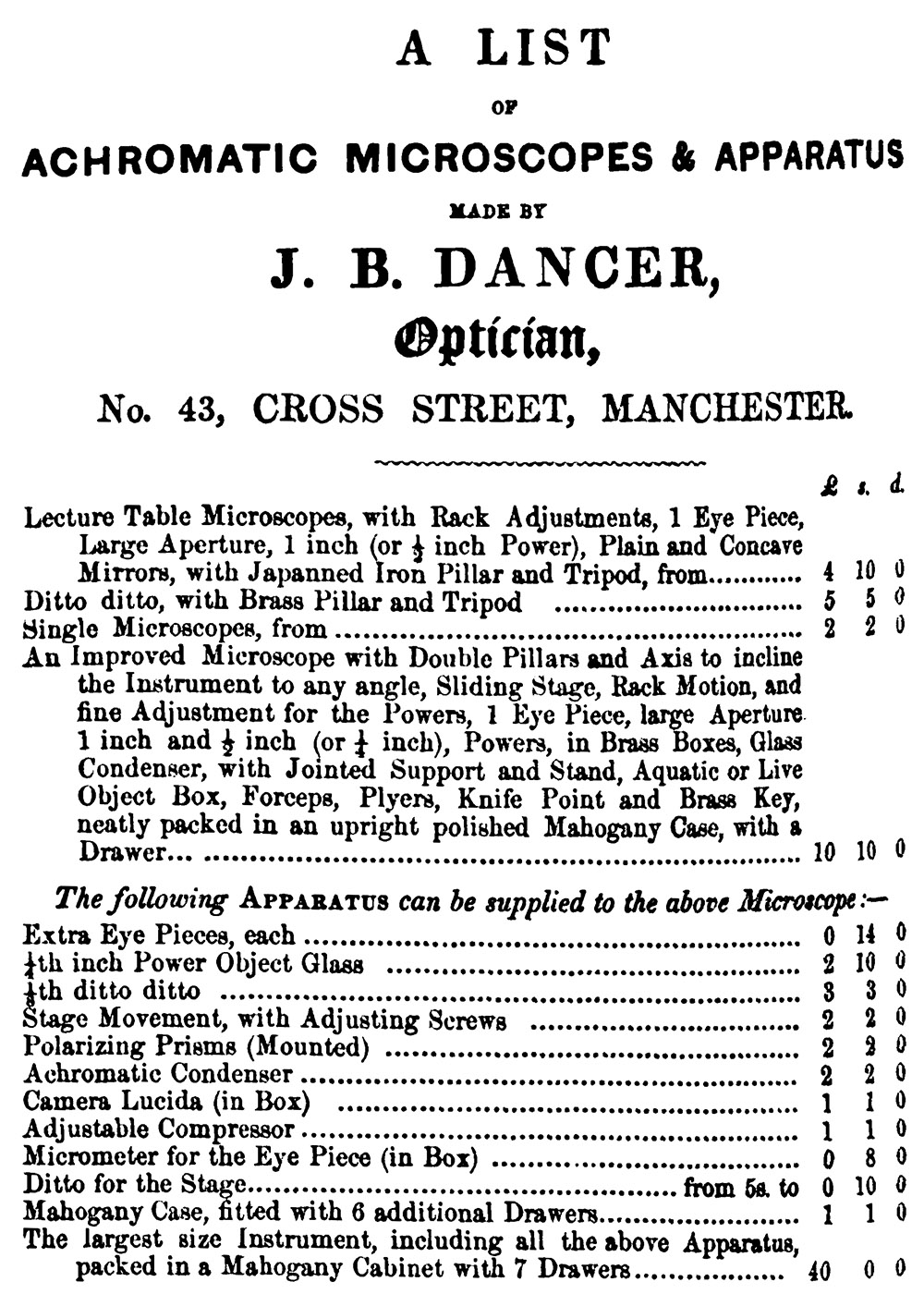

Figure 23.

Dancer had relocated to 43 Cross Street, Manchester by 1848. He advertised in John Quekett’s 1848, first edition of “A Practical Treatise on the Use of the Microscope”.

Figure 24.

A circa 1848 Dancer microscope. It features a “Jackson limb”, a design of George Jackson (1792-1861) in which the body tube and stage are mounted onto a single metal piece, making imaging much more stable than earlier microscopes such as those shown above in Figures 17 and 18. This model, or the one shown in Figure 22 (above), was probably the one described by John Quekett in his 1848 “Practical Treatise on the Use of the Microscope”: “Another very excellent form of microscope is that constructed by Mr. Dancer, of 43, Cross-street, Manchester; it consists of a firm tripod of brass, from which rise two stout pillars, bearing at their upper extremities the trunnions that support a slightly curved arm, to which the stage and compound body are attached, somewhat after the plan of that of Mr. George Jackson. The compound body itself consists of two tubes, the outer one being attached to the arm by two saddle-pieces with screws; this tube is sprung at either end, and within it a smaller one can be moved up and down by rack and pinion, turned by a large milled head; this forms the coarse adjustment, whereas the fine is effected in a similar manner to that in Mr. Smith's and Mr. Varley's instruments; viz. by a lever attached to the small tube carrying the object-glasses, which is moved either up or down by a fine threaded screw. The stage is about four inches long, and two and-a-half broad, and on it slides an object-plate longer than the stage-plate, but about half its breadth. To the front of the stage may be fixed the forceps and a large condensing lens, if necessary.”

Figure 25.

Compound microscope with a folding tripod stand, circa 1850. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Figure 26.

Dancer binocular microscope, with engraved serial number 371. Adapted with permission from http://www.antique-microscopes.com/photos/dancer.htm .

Figure 27.

J.B. Dancer bar-limb / “Society of Arts” type compound microscope, ca. 1860s.

Figure 28.

Student-type compound microscope by J.B. Dancer, circa 1860s-1870s. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co118854/student-microscope-by-j-b-dancer-manchester-cir-student-microscopes .

Figure 29.

Another student-type microscope, similar to that shown in Figure 28, but with a cast iron base. Dancer’s name and address were included in the casting mold. Of relatively low quality, this may have been brought in from a wholesale manufacturer. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Figure 30.

Engraved as having been sold by J.B. Dancer, but most likely manufactured for the wholesale trade by Baker, circa 1870s-1880s. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

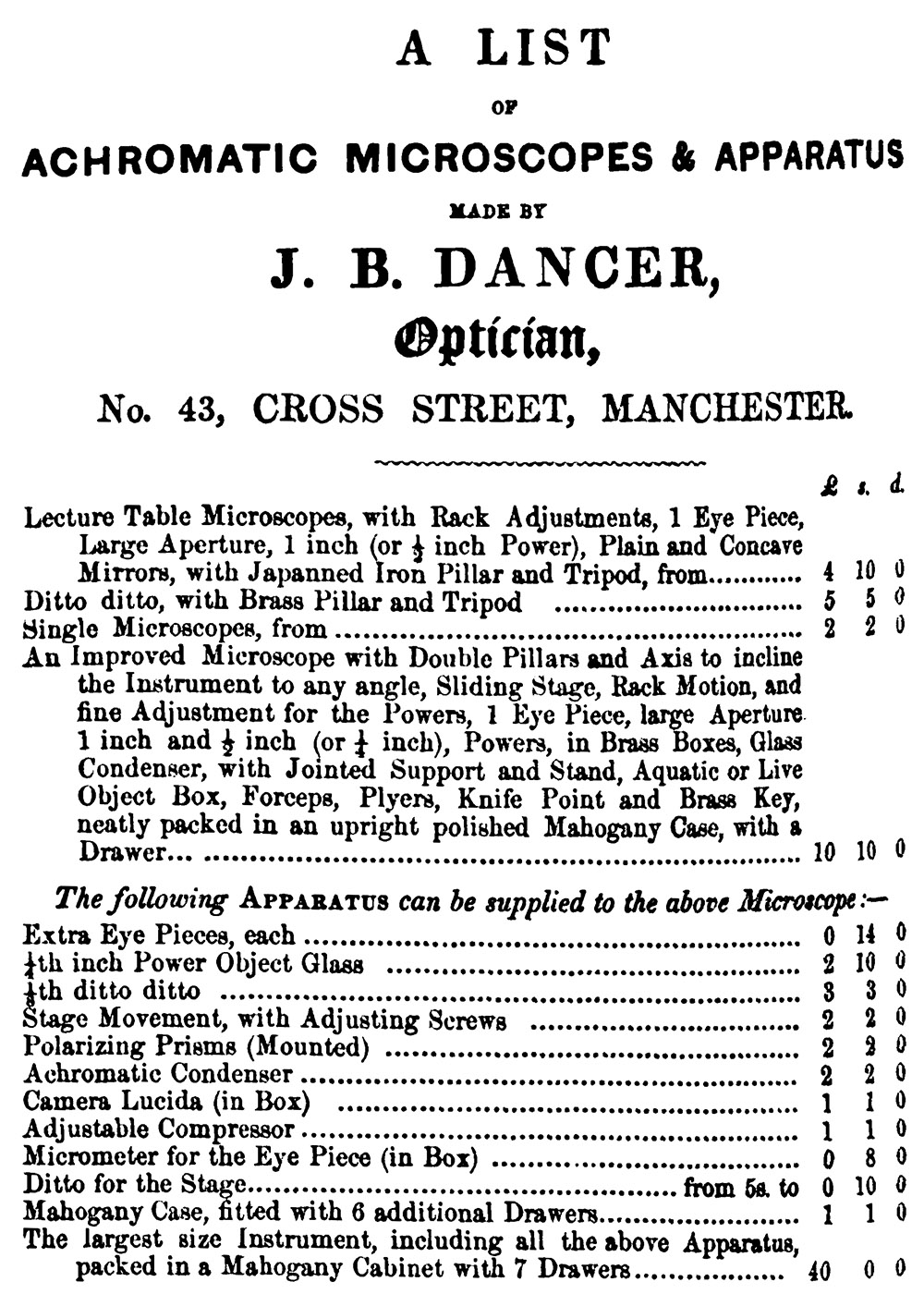

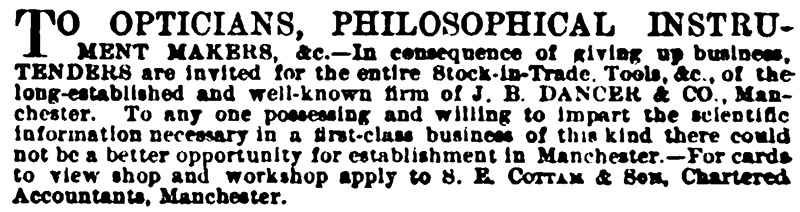

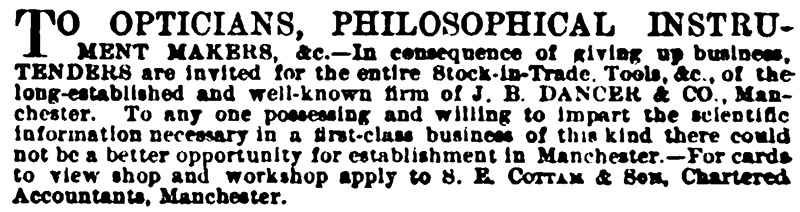

Figure 31.

J.B. Dancer and Company closed its doors in 1884. Advertisement from “The Athenaeum”, January 19, 1884.

Late in his life, probably two or three years before he died, John Benjamin Dancer dictated his autobiography to his granddaughter, Elizabeth Dancer (later Wilkie, lived 1871-1959). That manuscript came to light around the time of Elizabeth’s death, when her daughter made it known to the Manchester Microscopical Society. A transcript was then published in the Memoirs and Proceedings of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society, edited by W. Browning. I have relied upon Dancer’s memoir for information on a number of facets of his life.

Dancer stated, “John Benjamin Dancer was born in London on October 8th, 1812. His father and grandfather were manufacturers of Optical, Philosophical, and Nautical Instruments (to the trade)".

"Mr. Michael Dancer, the grandfather of the subject of this sketch, after serving for two years as Midshipman on board one of the Honourable East India Co. Canton tea ships, became an apprentice to Mr. Sangate, a favourite pupil of Jesse Ramsden, a celebrated London optician, son-in-law to Dollond, and Inventor of the Dividing Engine."

"Mr. Josiah Dancer, the father of Mr. J.B. Dancer, was born 1779. He served his apprenticeship to his father, Mr. Michael Dancer, and at the end of his apprenticeship he became principal assistant to Mr. Edward Troughton, then an eminent optician in London, manufacturer and inventor of many new forms of astronomical instruments. Mr. Josiah Dancer was principally engaged in the construction of Mr. Troughton’s new inventions."

"After a time, Mr. Dancer had to resign his situation, much to Mr. Troughton’s regret, and return home to take the management of his own father’s business, in consequence of the declining health of the latter. The late Mr. Simms took Mr. Josiah Dancer’s position and became Troughton’s partner.” (J.B. Dancer’s timeline is off here, as Josiah would have left the service of either John Troughton (1739-1807) or Edward Troughton (1756-1835) around 1800, while William Simms (1793-1860) joined Edward Troughton in 1826)."

Josiah Dancer had left Troughton to manage “Michael Dancer, mathematical instrument maker” at 52 Great Sutton Street, Clerkenwell. That business closed after Michael died in late 1816.

Josiah married Anna Maria Tolkien (1779-1815) on September 27, 1800. Our microscopist was named after his maternal grandfather, John Benjamin Tolkien (1752-1819). Anna Maria’s half-brother, George Tolkien, was the grandfather of author J.R.R. Tolkien. The two families evidently had another relationship in Tolkien and Dancer, “watch movement and tool manufacturer”, at 145 St. John's Street, London. That partnership dissolved in 1810, and was continued by George Tolkien.

Anna Dancer died in 1816. Josiah remarried in 1819, to Martha Lewis, after he moved the family to Liverpool.

According to J.B. Dancer, “In the year 1818, the family moved from London to Liverpool, and Mr. Josiah Dancer continued to carry on a similar business to that which he had been engaged in London, to which he added that of Public Lecturer on Natural History and various other subjects. He was an ardent student of physical science, including astronomy, optics, chemistry, electricity, and magnetism. Mr. Josiah Dancer with others founded the Liverpool Mechanics Institution. He greatly assisted the Institution in its early days by the gratuitous delivery of many courses of lectures on scientific and literary subjects, and with the assistance of a few literary friends the Lit and Phil Society of Liverpool was formed.”

“Mr. Dancer’s family at this time consisted of four daughters and one son, John Benjamin Dancer. The other sons had died in infancy.”

“After leaving a Dame’s School, J.B. Dancer’s education in arithmetic, algebra, trigonometry, and the dead languages were superintended by his father and Mr. Nixon and Mr. Bleasdale. He received instruction in French and writing.”

“At an early age, he was put to work first at grinding lenses for microscope objectives, and afterwards went through the mechanical training required in the manufacture of optical and philosophical instruments.” This sentence is particularly important, as Dancer specifically states that he manufactured microscope lenses for his father, indicating that Josiah manufactured microscopes. A small number of microscopes are known that are inscribed “J. Dancer, Liverpool” (Figure 32). J.B. Dancer’s statement supports the belief that they were manufactured by Josiah Dancer.

“At the age of 10 years (J.B. Dancer) assisted in the preparation of the experiments for his father’s lectures, and imbibed a great liking for experimental natural philosophy. Mr. Josiah Dancer had constructed for his own use a large solar microscope, the condensing lens of which was twelve inches in diameter. In favourable weather in the summer time he gave public exhibitions with this instrument. Some idea of its magnifying power may be formed by stating that by its means the human hair was magnified to 6 feet in diameter and cheese mites were magnified from four to five feet in length. The management of this instrument was deputed to his son J.B. Dancer and, as live objects were the most popular, he fished all the ponds for several miles distance around Liverpool to obtain the greatest variety of pond life. These he kept in numerous glass tanks for the purpose of observing their habits and changes. By this means he acquired a considerable amount of information which he afterwards found very useful. Mr. Josiah Dancer had a collection of many rare minerals. The forming of these into small cabinets, and mounting specimens for microscopic objects, fell to the share of John B. Dancer.”

”In the year 1835, Mr. Josiah Dancer died. Whilst making some astronomical observations, he was seized with a fit from which he never recovered."

“The business was carried on by his son, John B. Dancer. He also followed his father’s practice in delivering experimental lectures in natural philosophy at a number of large educational establishments in and around Liverpool.”

J.B. Dancer married soon after he inherited his father’s business. On March 22, 1836, he married Elizabeth Barrow (1819-1889). The pair had 8 children: Josiah W. Dancer (1837-1907), John Dancer (1839-1876), William Dancer (1841-1928), James Dancer (1844-1889), Elizabeth Eleanor Dancer (1846-1925), Anna Maria Dancer (1847-1896), Charles Henry Dancer (1850-1939), and Catherine Dancer (1853-1943). After J.B. Dancer went blind in 1878, son Josiah continued operation of the optical shop. Elizabeth and Anna ran a second shop that sold both J.B. Dancer’s microphotographs and those of their own making.

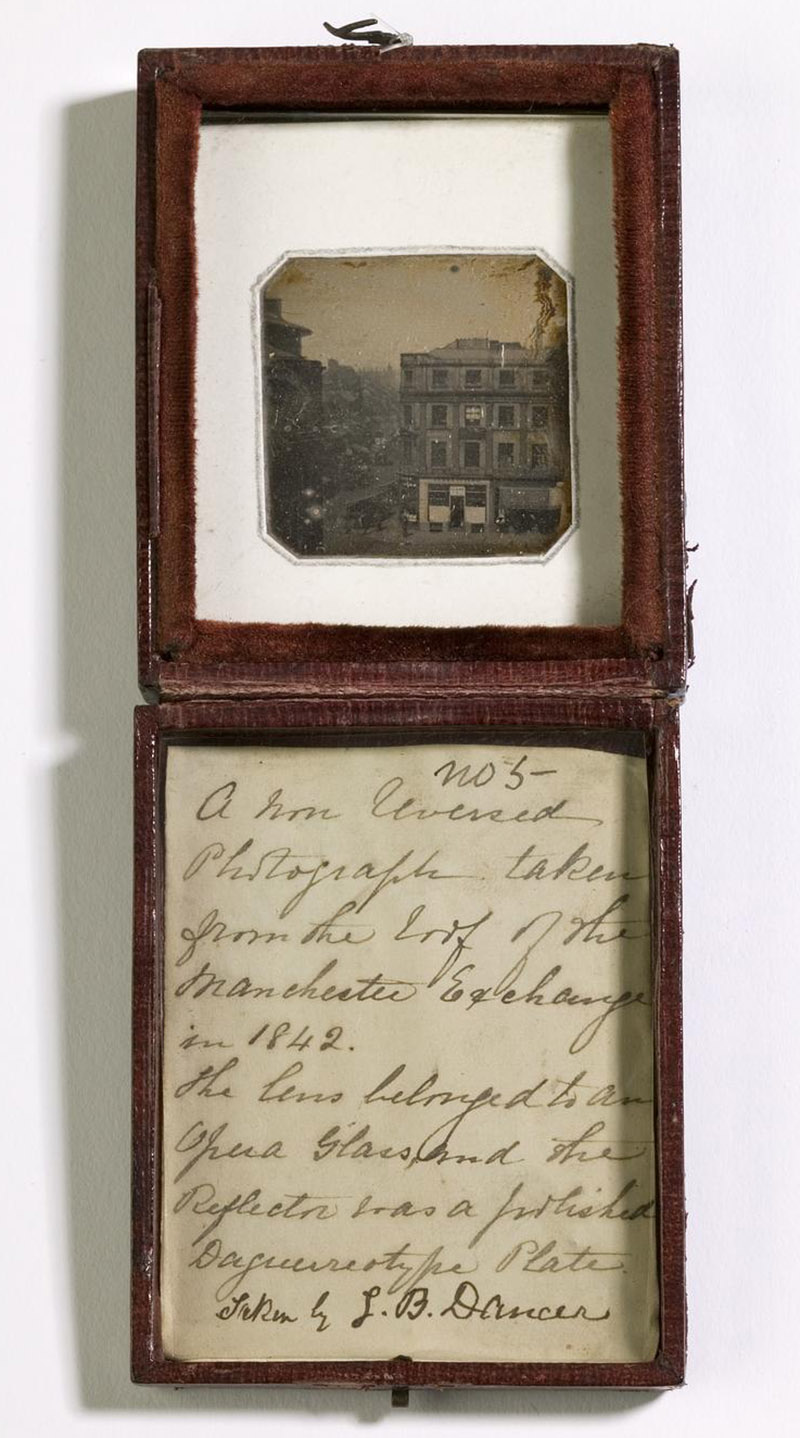

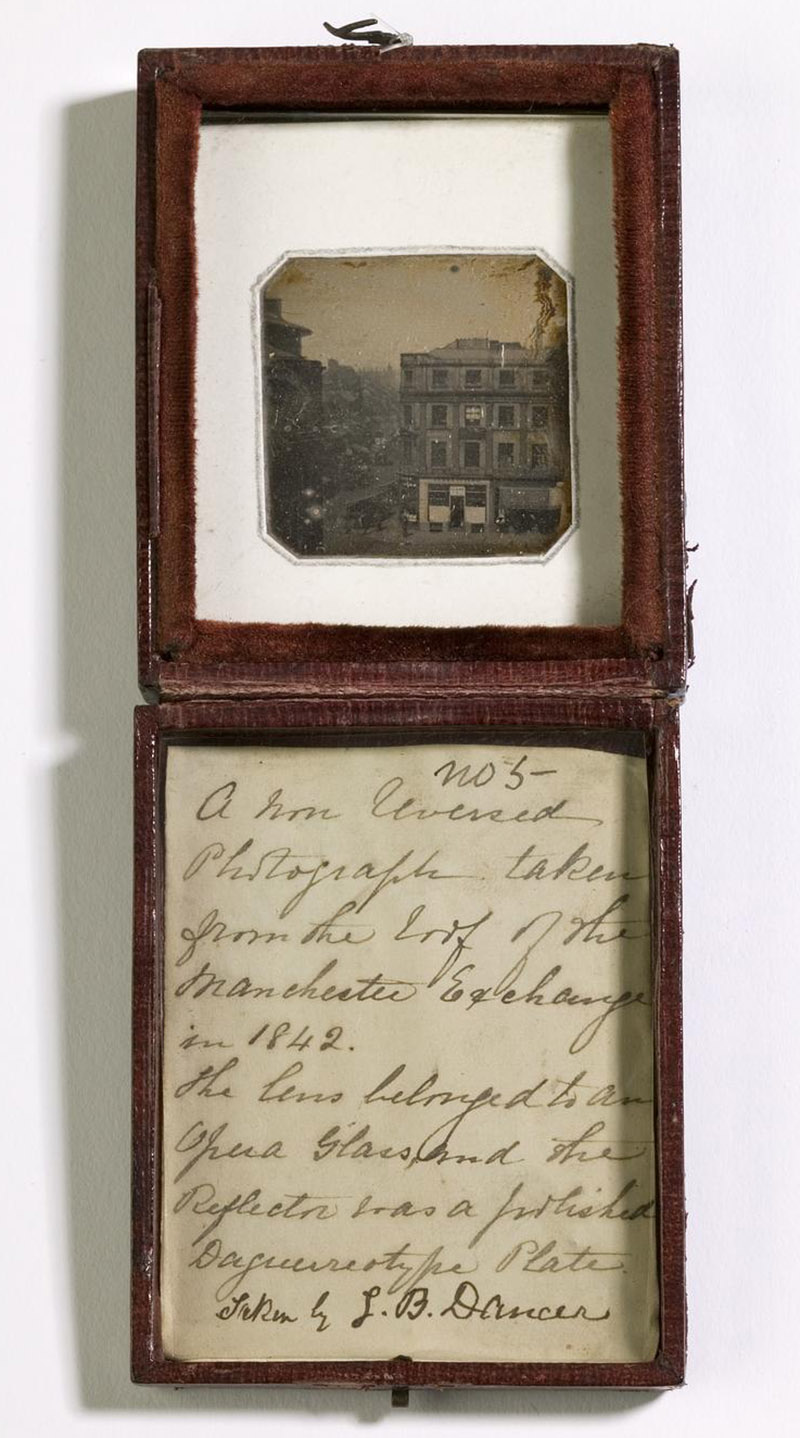

Dancer was an early practitioner of photography. In the late 1830s, he copied the silver chloride on paper method of William Fox Talbot (1800-1877), and “became engaged to a considerable extent in preparing this paper for commercial purposes”. Around 1840, Dancer learned the silver plate photographic process of Louis Daguerre (1787-1851). “He afterwards obtained from Daguerre a complete set of his apparatus and succeeded in obtaining pictures of the principal buildings in Liverpool, (and) he also publicly exhibited the process.” Dancer wrote that upon his “arrival in Manchester in the year 1841, he found that the daguerreotype process of photography had not been practiced there so far as he could discover, and he had the pleasure of showing and teaching the process to many of the influential and scientific men in the town”. Figure 33 shows a scenic daguerreotype of Manchester that was taken by Dancer in 1842.

Dancer further stated, “During a lecture at the Mechanic’s Institution, Liverpool, by the aid of the gas microscope, he produced the image of a flea on a Daguerrotype plate magnified to six inches in length. This sections of wood, the itch insect, and many other microscopic objects were copied in like manner. He also attempted minute microscopic photographs, the size of the particles of mercury, however, which formed the picture limited the reduction.”

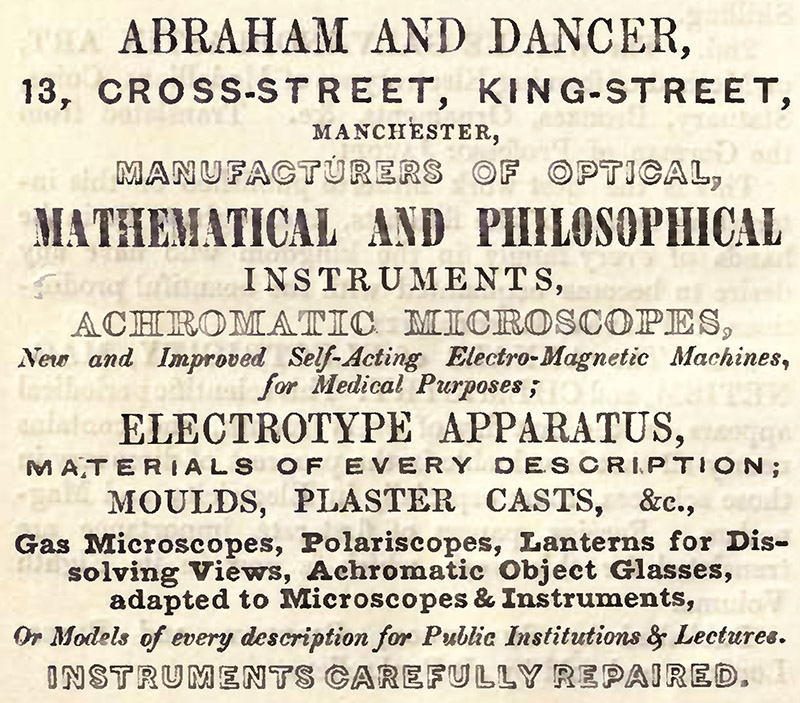

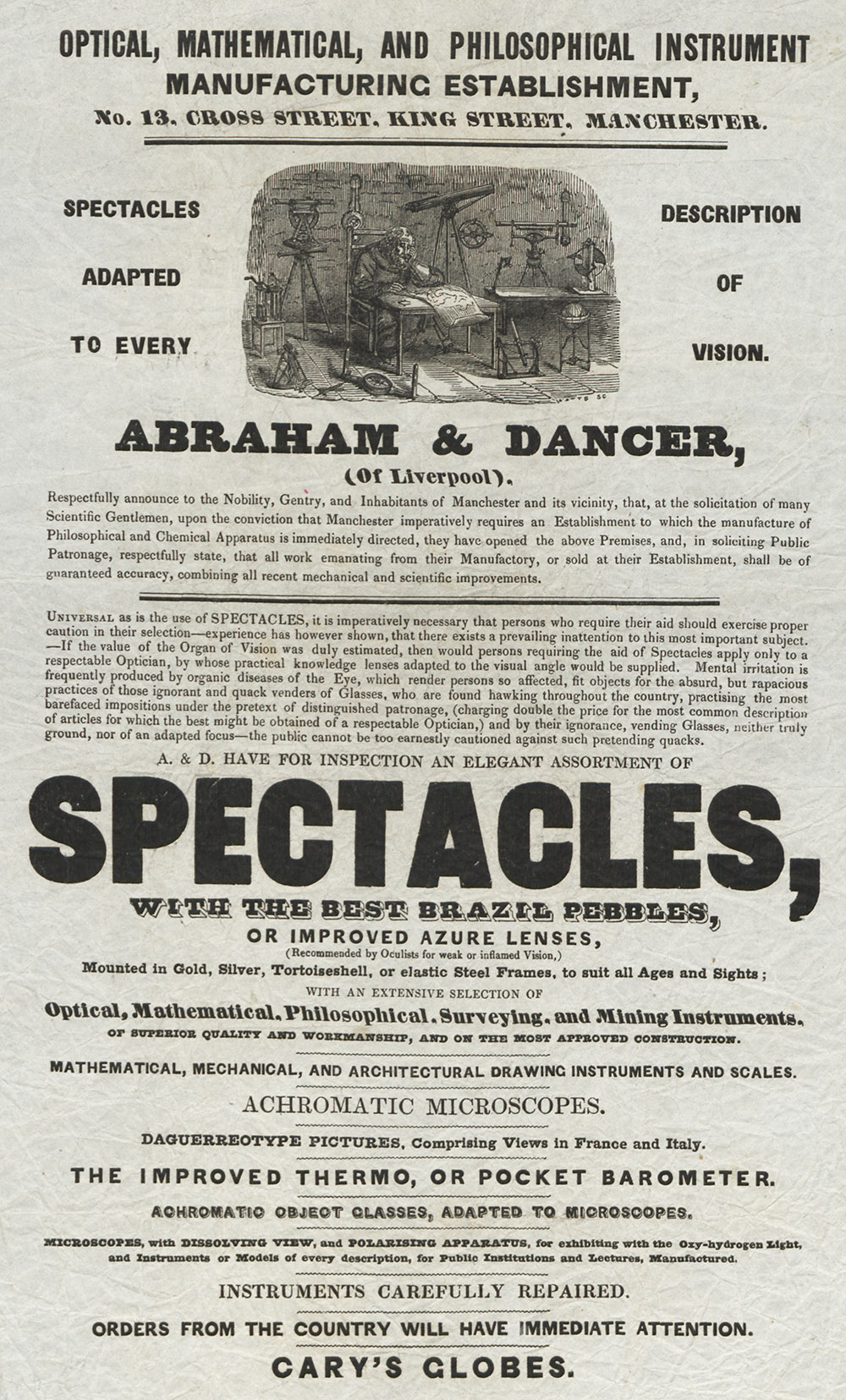

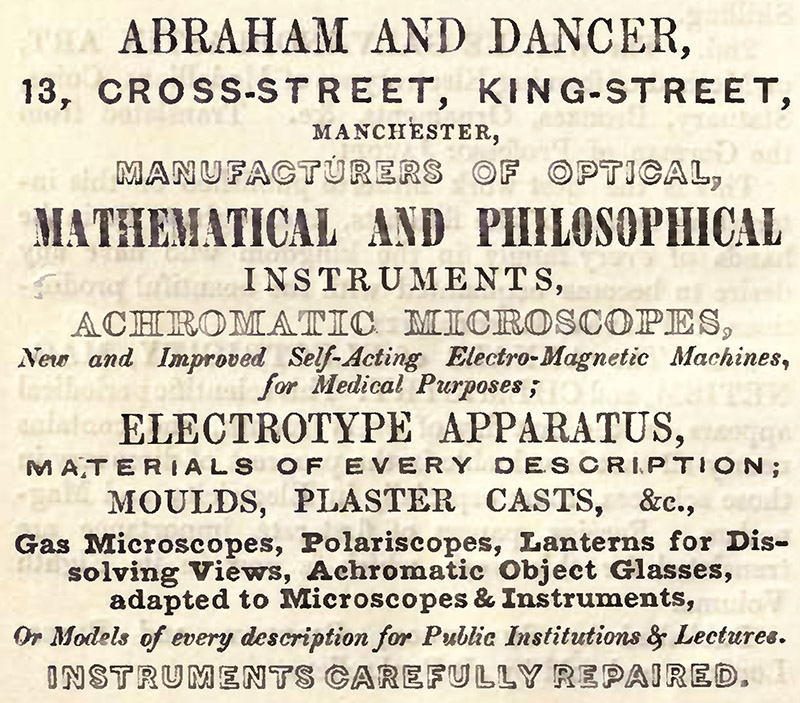

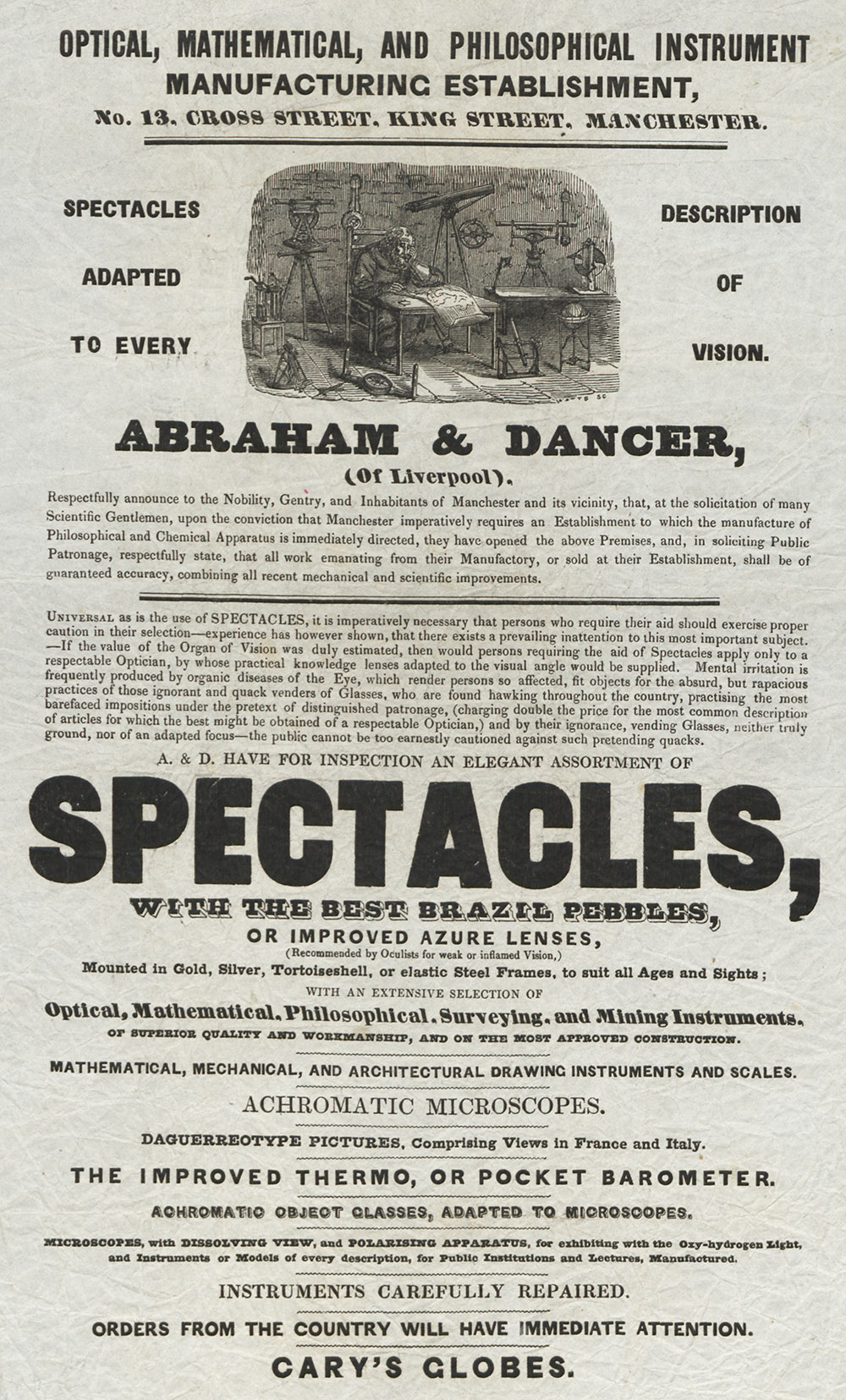

In 1841, Dancer closed his Liverpool shop and entered into partnership with Abraham Abraham (ca. 1799 - 1863). Abraham had operated an optical/scientific business in Liverpool since 1817. In 1838, Abraham had expanded his business into Glasgow, by forming the “Abraham & Company” partnership with Simon Cohen (1805-1894), which lasted until Cohen bought out the business in 1843. A similar situation occurred between Abraham and Dancer, with the younger man moving to 13 Cross Street, Manchester, to open and manage a shop as “Abraham and Dancer”, while Abraham maintained his original Liverpool shop as simply “A. Abraham”. (Figure 19). Details on the life, businesses, and works of Abraham Abraham can be seen elsewhere on this web site.

An 1841 advertisement declared that A. Abraham, Abraham and Dancer, and Abraham and Company “manufactured and sold … a microscope … with jointed pillar and tripod stand, two sets of achromatic object-glasses, two Huygenian eye-pieces, forming a combination of five magnifying powers, varying from 30 to 250 times linear” (Figure 19). These were probably microscopes such as shown in Figures 17 and 18, above. Other advertisements indicate that they manufactured and sold eyeglasses and a wide variety of optical, scientific, and engineering apparatus (Figures 34, 35).

Dancer: “Before leaving Liverpool, Mr. Dancer had assisted the late Mr. Abraham, optician of that town, in the construction of cheap achromatic microscopes, which that gentleman thought was an instrument much needed by the medical profession. When Mr. Dancer came to Manchester in 1841, he brought with him some of the moderate priced instruments. So far as he was aware, there were then only two achromatic microscopes in the city, and the introduction of the cheap achromatic microscopes were hailed with satisfaction by numerous medical men to whom they were exhibited by Mr. Dancer. The old fashioned Culpeper and other microscopes with single lenses were speedily discarded.”

James P. Joule and others later wrote, “When Mr. Dancer established himself as an optician in Manchester, his presence soon made itself felt amongst the few microscopists then living in the district. Good microscopes were then costly, and worthless ones very common. Mr. Dancer successively brought out several forms of instruments, as excellent in their mechanical and optical arrangements as they were moderate in price. Instruments fully equal to the requirements of original research were thus brought within the reach of many whose observing faculties were more conspicuous than their financial resources. It would be difficult to overestimate the stimulus which Mr. Dancer thus gave to Manchester microscopy; it cannot be doubted that the present energy of our local microscopists is the direct outcome of the impulse which their means of research then received.”

Dancer: “in 1842, Mr. Dancer was appointed to superintend and keep in order the first telegraphic wires in Manchester by Messrs. Cook and Wheatstone. The wires were laid from the Victoria Station, Strangeways, to Miles Platting. He also made many telegraphic instruments for Messrs. Cook and Wheatstone. He felt obliged to decline the appointment in consequence of its interference with his optical business."

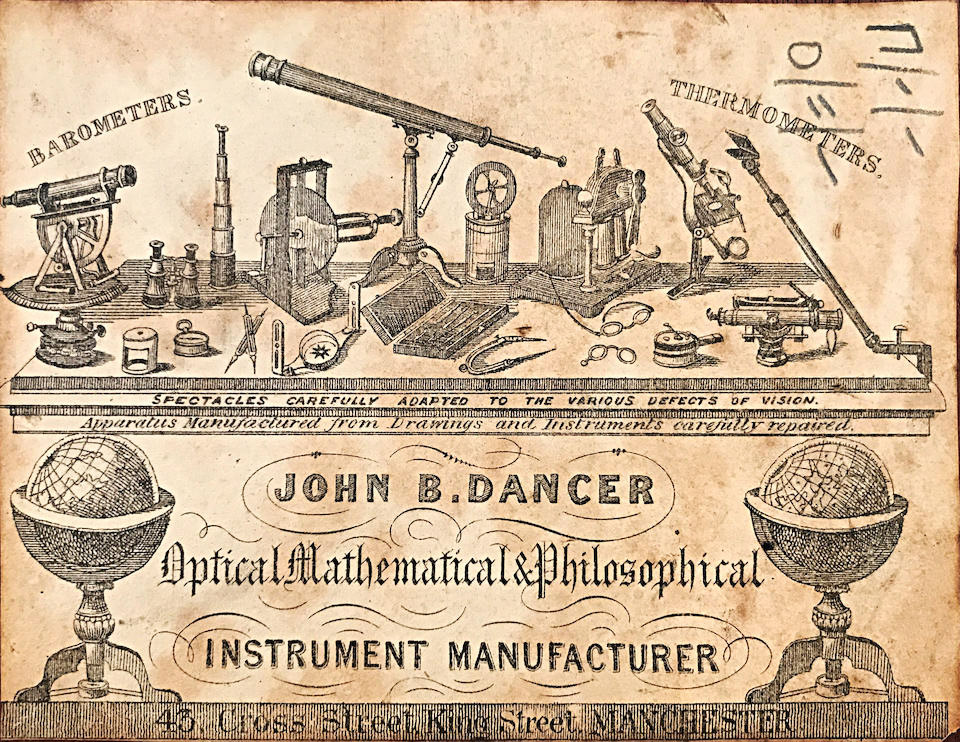

The Abraham and Dancer partnership was dissolved in 1844, as recorded in The Gazette, “Notice is hereby given, that the partnership heretofore subsisting between us the undersigned, as Opticians, at Manchester, in the county of Lancaster, under the firm of Abraham and Dancer, is dissolved, by mutual consent, as on the 31st day of December last. All debts due from or to the late partnership will be paid and received by the undersigned John Benjamin Dancer, by whom the business will hereafter be carried on. - Dated this 31st day of March, 1845, Abraham Abraham, John. B. Dancer”.

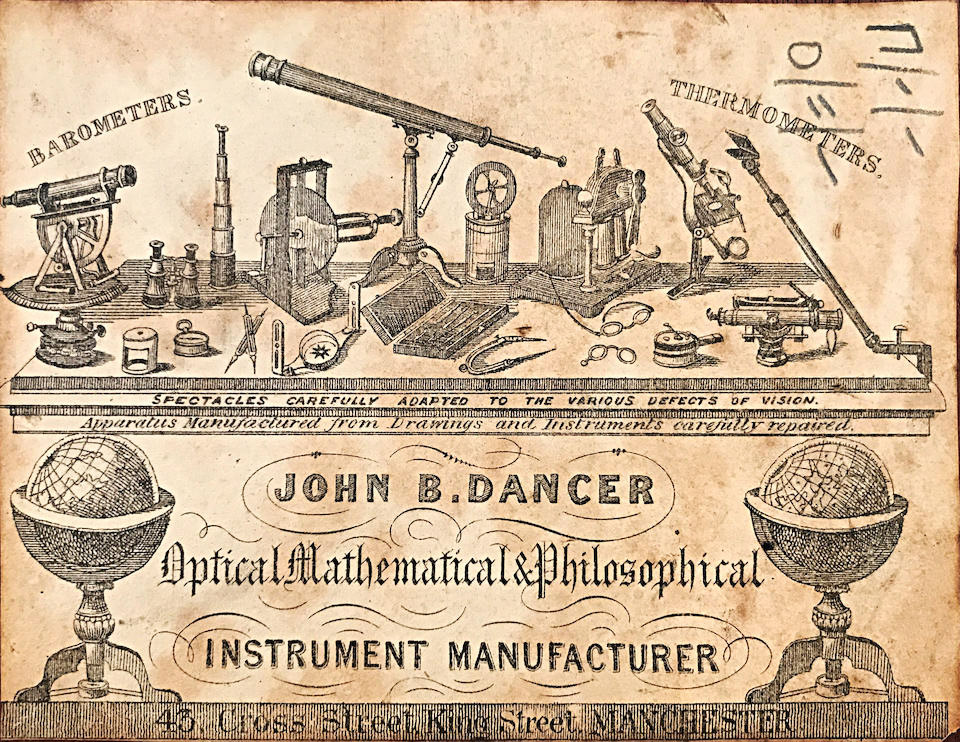

Circa 1846-1848, the number of Dancer’s shop changed from 13 to 43 Cross Street. This may have been a renumbering of the road. Many of Dancer’s early instruments include notice of his address, so the street number may be useful in dating apparatus.

Dancer: “At this period Mr. Dancer was closely connected with the Manchester Mechanics Institution, and contributed in various ways to their annual exhibitions. He supplied them with one of his improved dissolving view lanterns. Illuminated by the oxyhydrogen light, the lantern exhibitions proved very attractive and remunerative. Beautiful paintings were exhibited, illustrating subjects of historical interest, many views reaching the amount of £5 each. During these lectures, Mr. Dancer added the charm of photography by exhibiting a series of beautiful photographs on albumen, taken by Ferrier of Paris for the stereoscope. Mr. Dancer removed the gray film from the back of these photographs and converted them into slides for the lantern. Now that the introduction of photography in connection with the magic lantern had become instituted, its value as an educational instrument became far more apparent, for although many of the hand painted slides were very beautiful and artistically produced, yet an artist, however eminent, can never aspire to the accuracy of photography in minute detail.”

“When Scott Archer’s collodian process was made known in 1850-52, amateurs hailed it with delight, as it enabled them to commence landscape photography on a considerable scale at a trifling expense with but a small amount of labour in comparison with the daguerreotype process. Mr. Dancer at once re-commenced his experiments in microscopic photography.”

“Sir David Brewster exhibited in the year 1856 Mr. Dancer’s microscopic photographs to the members of the scientific academies of Paris. One photographer in Pari, of the name of Dagron, was not only impudent enough to take out a patent for Mr. Dancer’s invention, but also to commence an action against one of Mr. Dancer’s customers who supplied the public with is microscopic photographs. Of course, the patent could not be sustained under such circumstances.”

“Sir David Brewster also exhibited them to the nobility at Florence and Rome, amongst others, to the Pope and other officials at the Vatican.”

“Mr. Dancer presented a dozen microscopic copies of Winterhalter’s paintings of our Royal Family to the Queen. Prince Albert, who was present at the time, said that he was the photographer and that the photographs must have been intended for him. These minute pictures are now to be found in the cabinets of the curious in all parts of the civilized world.”

“The process of photographic reduction has been employed by Mr. Dancer for the production of micrometers for telescopes and microscopes, and diffraction gratings.”

Dancer was elected Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society on March 9, 1855.

At the 1862 International Exhibition in London, Dancer won a Medal in Class XIII, Philosophical Instruments, for “the general excellence of his microscopes and microscopic photographs”, and an Honourable Mention in Class XIV, Photography and Photographic Apparatus, for “microscopic photographs, landscapes, and portraits.”

According to Dancer, he began to suffer the effects of diabetes in 1870. He wrote, “by strict attention to diet, for a number years he was enabled to keep the complaint in abeyance”. That same year, “his sight began to fail. Three operations were performed on his eyes, for glaucoma”. By 1878, “ill health and failing vision prevented him from attending to business”.

Eldest son Josiah ran the optical and scientific shop as J.B. Dancer & Company, before closing it down in 1884 (Figures 31 and 32).

Daughters Elizabeth and Anna operated a separate shop, at 436 Stockport Road, where they continued to produce and sell microphotographs (Figure 31). Letters from artist James Nasmyth (1808-1890) to J.B Dancer confirm that Elizabeth and Anna Dancer produced new microphotographs: “Your daughters must be most skillful in the photo art to be able to reduce my pen sketches in such microscopic size as you name! Such a result is very creditable to their skill” (August 15, 1883), and “Many, many thanks for your kind and very valued present of these marvelously minute photo copies of some of my fancy etchings, they are wonderful examples of your daughters’ skill as a micro-photo artist! … I like ‘The Fairies’ best for their clearness of the rendering of the details.” (November 2, 1883). Dancer microphotographs 411 through 417 reproduced Nasmyth’s engravings, the “The Fairies” being number 412. Of note, Bracegirdle and McCormick’s The Microscopic Photographs of J.B. Dancer attributed Dancer slide 417 (Nasmyth’s “Robinson Crusoe”) to Richard Suter, while the above-quoted letters implicate the Dancer daughters as being the actual producers. Their 1884 advertisement names microphotographs that are known to be labeled with numbers 363 through 372. One might reasonably conclude that they also produced many other Dancer microphotographs in that number range.

In 1883, a collection was taken up to establish an annuity to support J.B. Dancer and his wife, noting, “It is sad to have to say, that notwithstanding Mr. Dancer's talents and achievements, he is now living in very straitened circumstances, is moreover afflicted with almost total blindness, and therefore unable to follow the optical business to which his life has been devoted. It is not an unusual thing for a man of great mechanical ingenuity and skill to be an indifferent man of the world, and so it has been with him; as a business man he has been a failure. He has made improvement after improvement, invention after invention, any one of which might pushing hands have made a fortune; but more interested in science than in money-making, he has allowed the golden chances to become public property, and has thus remained poor himself, while the world has reaped the advantage of his labours. Mr. Dancer is now in his seventy-fourth year, and we beg respectfully to suggest that in his hour of darkness the world should pay back to him something for that which it has freely received at his hands.”

John Benjamin Dancer died on November 22, 1887.

Microscope slide-maker Richard Suter (1864-1959) purchased the Dancers’ microphotographs negatives, and the right to reproduce them, in 1896.

Anna Dancer died in early 1896, at the age of 49.

The 1901 national census recorded Elizabeth Dancer as working as a domestic housekeeper for an accountant. By 1911, she had moved in with niece Elizabeth and her husband, John Wilkie. It was Elizabeth Wilkie who wrote down J.B. Dancer’s autobiography and later made it publicly available. Elizabeth Dancer died in 1925, at the age of 80.

After shuttering the J.B. Dancer shop in 1884, son Josiah W. Dancer continued to work as an optician, according to census records, although he likely worked for an employer. The 1901 census listed him as a “retired optician”, age 64, living with his younger brother, William, who managed a chemical business. Josiah W. Dancer died in 1907, at 71 years of age.

Figure 32.

A microscope that is signed “J. Dancer, Liverpool”, most likely produced by J.B. Dancer’s father, Josiah, ca. 1830. Adapted by permission for nonprofit, educational purposes.

Figure 33.

“A non reversed photograph taken from the roof of the Manchester Exchange in 1842. The lense belonged to an opera glass and the reflector was a polished daguerreotype plate. Taken by J.B. Dancer”. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://blog.scienceandindustrymuseum.org.uk/j-b-dancer/

Figure 34.

1842 advertisement for Abraham and Dancer, 13 Cross Street, Manchester. From William Sturgeon’s “Lectures on Electricity”.

Figure 35.

ca. 1842 broadsheet advertisement from Abraham and Dancer. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://mhs.web.ox.ac.uk/collections-online#/item/hsm-catalogue-30505

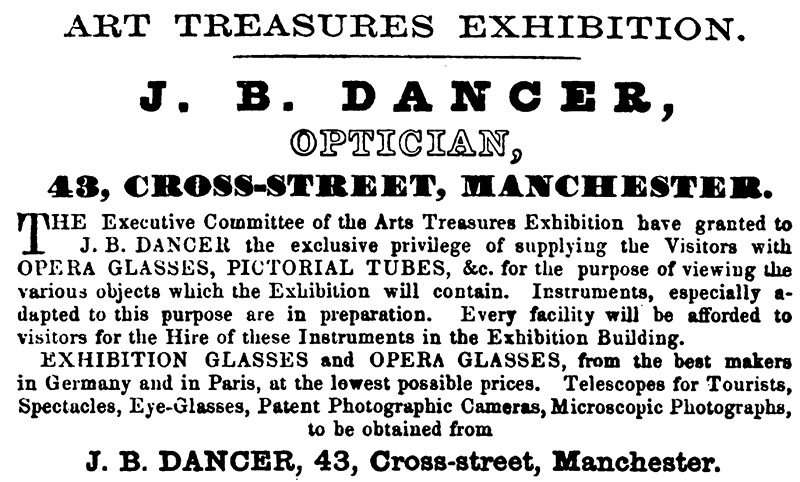

Figure 36.

A J.B. Dancer trade label, illustrating a microscope and many other types of scientific and engineering apparatus, as well corrective eyeglasses. The address of 43 Cross Street dates it to after 1846-1848.

Figure 37.

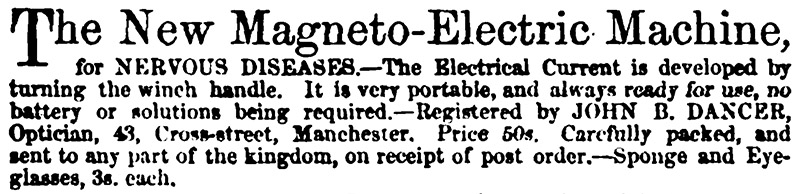

1856 advertisement, from “The Lancet”.

Figure 38.

1857 advertisement, from “The Strangers’ Guide to Manchester”.

Figure 39.

1863 advertisement, from H.W. Heaton’s “Notes on Rifle-Shooting”.

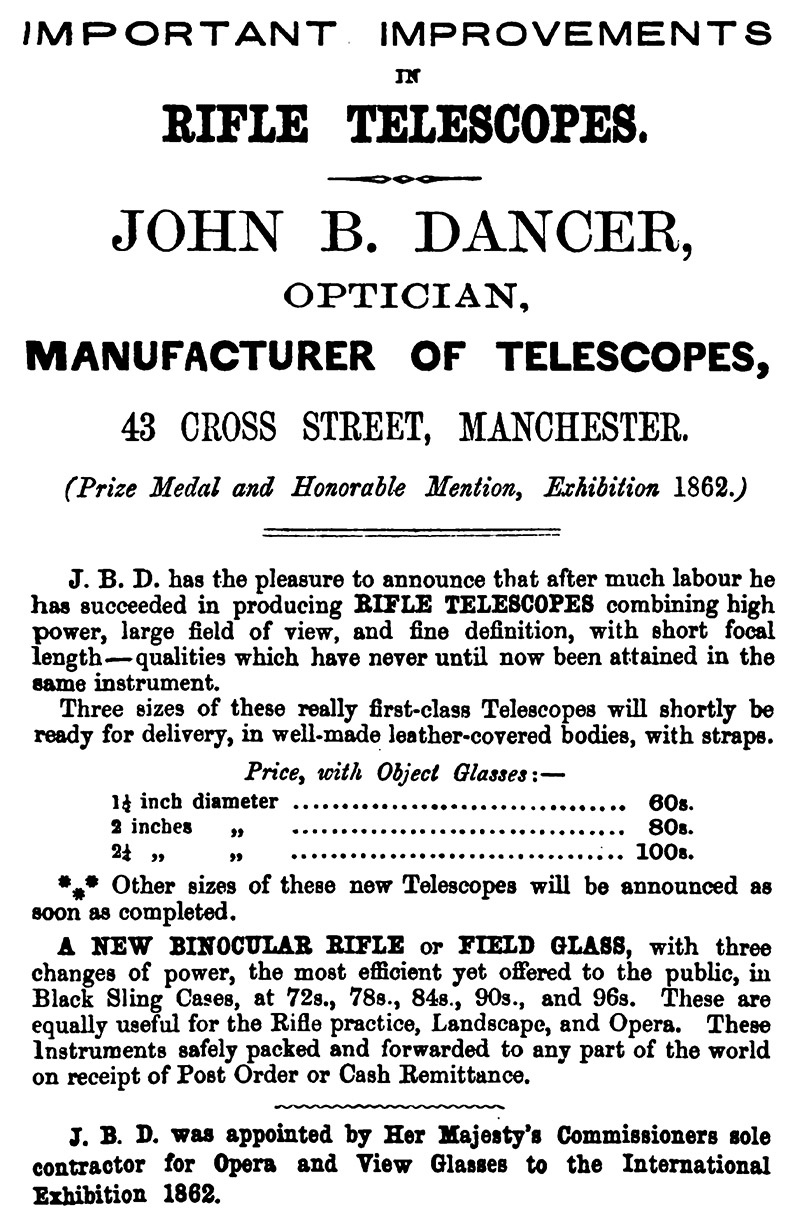

Figure 40.

1878 advertisements, both of which appeared in the August 30, 1878 issue of “The English Mechanic and World of Science”.

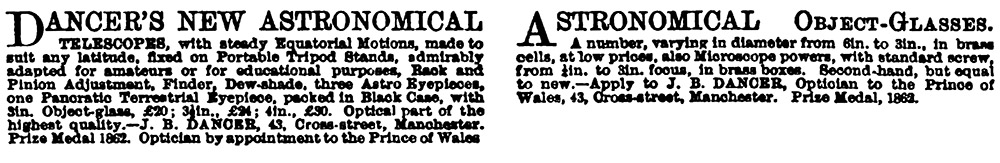

Figure 41.

1882 advertisement, from “The Field Naturalist and Scientific Student”.

Figure 42.

Photograph of J.B. Dancer that accompanied Henry Garnett’s 1927 biography, “taken from the original negative of a stereoscopic photograph formerly in the possession of his family”.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Barry Sobel, Joe Zeligs, James McClintock, and Allan Wissner for helpful discussions and/or providing images.

Resources

The Athenaeum (1841) Advertisement for Abraham and Dancer, et al., October 16 issue, page 799

The Athenaeum (1844) Advertisement for Abraham and Dancer, et al., October 5 issue, page 911

The Athenaeum (1884) Advertisement for J.B. Dancer & Co., January 19 issue, page 74

Baines’ Directory of Liverpool (1824) “Dancer, Josiah, optician, 14, New quay; h. 20, Grafton st.”, page 235

Baptism record of John Benjamin Dancer (1812) Parish records of Saint John Clerkenwell, accessed through ancestry.com

Bracegirdle, Brian (1987) A History of Microtechnique, Second Edition, Science Heritage Ltd., Lincolnwood, Illinois, pages 190-191

Bracegirdle, Brian (1998) Microscopical Mounts and Mounters, Quekett Microscopical Club, London, pages 28-29, 132, 190, and 196, and Plates 14-B, 14-C, 14-D, 14-E, 14-F, 14-G, 43-G, 46-O, 46-P, 46-Q, and 46-R

Bracegirdle, Brian, and James McCormick (1993) The Microscopic Photographs of J.B. Dancer, Science Heritage Ltd., Chicago

Brittain, Thomas (1883) The beginnings of microscopic study in Manchester, The Field Naturalist and Scientific Student, pages 148-150

Burial record of Michael Dancer (1816) Parish records of Saint James Clerkenwell, accessed through ancestry.com

Burial record of Anna Dancer (1815) Home: “Great Sutton Street”, Records of Bunhill Fields Burial Ground, City Road, accessed through ancestry.com

Chemical Trade Journal (1887) The late Mr. J.B. Dancer, pages 258-259

Dancer, John B. (1868) Microscopical examination of coal ash from the flue of a furnace, Annual of Scientific Discovery, pages 178-180

England census and other records, accessed through ancestry.com

The English Mechanic and World of Science (1878) Advertisements from J.B. Dancer, August 30 issue

The Field Naturalist and Scientific Student (1882) Advertisement from J.B. Dancer & Co., June issue

Fletcher, J.R. (2022) Dancer’s chemical slides, Quekett Journal of Microscopy, Vol. 44, pages 291-296

“Galadhorn” (2018, accessed May, 2023) John Benjamin Tolkien (1752-1819): a summary, http://tolkniety.blogspot.com/2017/05/john-benjamin-tolkien-1753-1819-summary.html

Garnett, Henry (1927) John Benjamin Dancer, instrument maker and inventor, Memoirs and Proceedings of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society, pages 7-20

Gazette (1845) Notice of dissolution of Abraham and Dancer, page 1027

Gore’s Directory of Liverpool (1827) Opticians, “Dancer Josiah, 20, Grafton st”, page 332

Hallett, Michael (1986) John Benjamin Dancer 1812-1887: A perspective, History of Photography, Vol. 3, pages 237-255

Heaton, Henry W. (1863) Notes on Rifle-Shooting, Second Edition, Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts & Green, London, advertisement from J.B. Dancer in back

Holden’s Triennial Directory (1805) “Dancer Mich. mathematical instrument-maker, 52, Great Sutton st. Goswell-st.”

Joule, J.P., W.C. Williamson, B. Stewart, J. Dale, L.H. Grindon, S. Platt, C. Bailey, J. Birchall, and A. Heywood (1886) Announcement of the “Dancer Subscription”, The Chemical Trade Journal, pages 305-306

The Kaleidoscope (1825) Announcement for lectures by Josiah Dancer at the Liverpool Apprentices and Mechanics’ Library, page 332

The Lancet (1856) Advertisements from J.B. Dancer, November 15 and other issues

London Directory (1811) “Dancer and Son, mathematical instrument maker, 53, Red Lion street, Clerkenwell … Dancer Michael, mathematical instrument-maker, 55, Great Sutton street, Clerkenwell … Dancer Joseph, jun. mathematical instrument maker, 5, Corporation lane, Clerkenwell”

Manchester Microscopical & Natural History Society (accessed May, 2023) John Benjamin Dancer, 1812-1887, 19th Century Manchester Instrument Maker, Inventor & Inventor of Microphotography, http://www.manchestermicroscopical.org.uk/danchom.html

Mantell, Gideon A. (1846) Thoughts on Animalcules, J. Murray, London, page 111

Marriage record of Josiah Dancer and Anna Maria Tolkein (1800) Parish records of Saint James, Clerkenwell, accessed through ancestry.com

Marriage record of Josiah Dancer and Martha Lewis (1819) Parish records of Saint Nicholas, Liverpool, accessed through ancestry.com

Medals and Honourable Mentions Awarded by the International Juries (1862) pages 197 and 207

Memoirs and Proceedings of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society (1870) Microscopical and Natural History Section, Vol. 9, page 64

Memoirs and Proceedings of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society (1964) John Benjamin Dancer, F.R.A.S., 1812-1887, an autobiographical sketch, with some letters, forward by W. Browning, pages 115-142

Microscopical News and Northern Microscopist (1882) The dust from boiler flues under the microscope, Vol. 2, pages 316-317

Microscopical News and Northern Microscopist (1884) Atmospheric dust, Vol. 4, pages 109-110

Microscopical News and Northern Microscopist (1884) Advertisements from J.B. Dancer & Co. and from E.E. & A.M. Dancer, Vol. 4, January issue

The National Register (1808) Partnerships dissolved, “Tolkien and Dancer, St. Sepulchre, clock and watch tool dealers”, page 601

Post Office Directory of London (1814) “Dancer Michael, Mathematical Instrument-maker, 52, Great Sutton-street, Clerkenwell”, page 86

Quekett, John (1848) A Practical Treatise on the Use of the Microscope, Bailliere, London, pages 97-98 and advertisement in back

Sidebotham, Joseph (1859) On micro-photography, The Photographic Journal, Vol. 6, page 91

The Strangers’ Guide to Manchester (1857) Advertisement from J.B. Dancer

Sturgeon, William (1842) Lectures on Electricity, Sherwood, Gilbert and Piper, London, Advertisement from Abraham and Dancer in back

Universal British Directory (1791) London, “Dancer Michael, Mathemat. Instrument-maker, 11, New-street-square”, page 120

Warren, Stanley E. (2014) The Micrograph, Micro Miscellanea, the Newsletter of the Manchester Microscopical and Natural History Society, Issue No.85, Spring, pages 14-24