John Harbord Lewis, 1848 - 1906

by Brian Stevenson

last updated August, 2017

J.Harbord Lewis was an amateur botanist, whose interests evolved to desmids, then other microscopical items, during the 1880s. His exchange advertisements suggest that he quit those hobbies around 1890. His slides are of varying quality: some were made for his own collection, while others were intended for exchange or for sale.

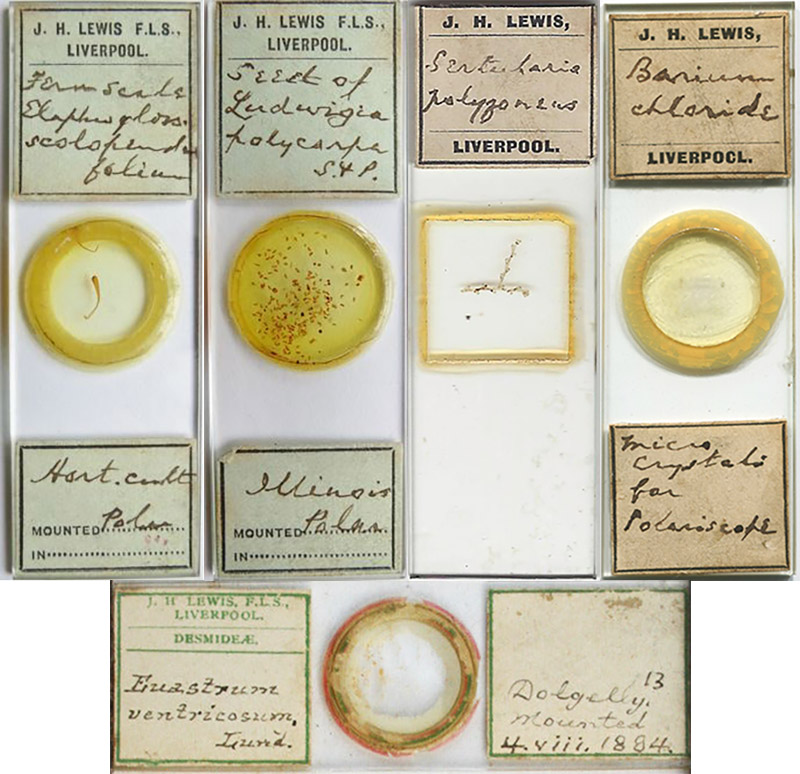

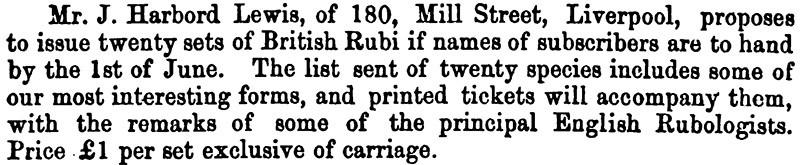

Figure 1.

A selection of microscope slides by J. Harbord Lewis. The lower slide, of desmids, is dated August 4, 1884 (“viii” is month 8 of the Society of Friends/”Quaker” calendar, i.e. August). Bracegirdle’s “Microscopical Mounts and Mounters” illustrates Lewis slides that are dated 1883 and 1886. Images from the author’s collection or adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from internet auction sites.

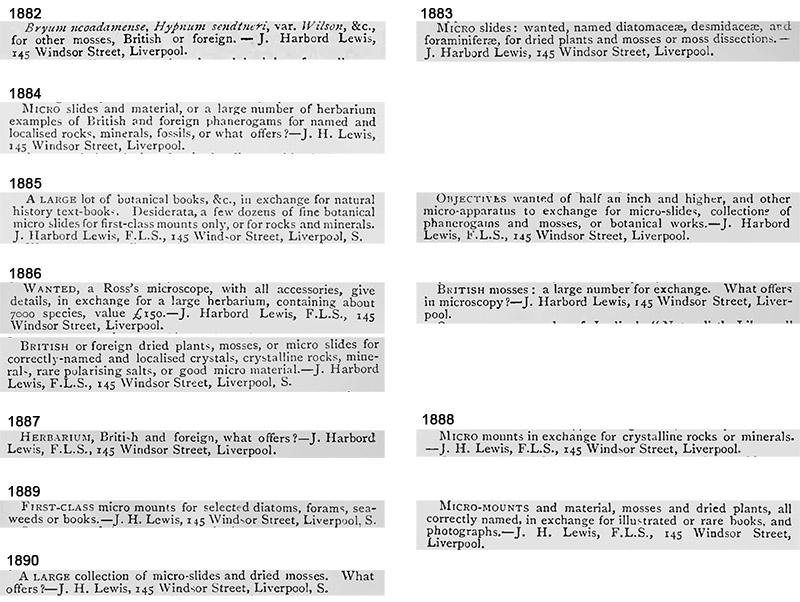

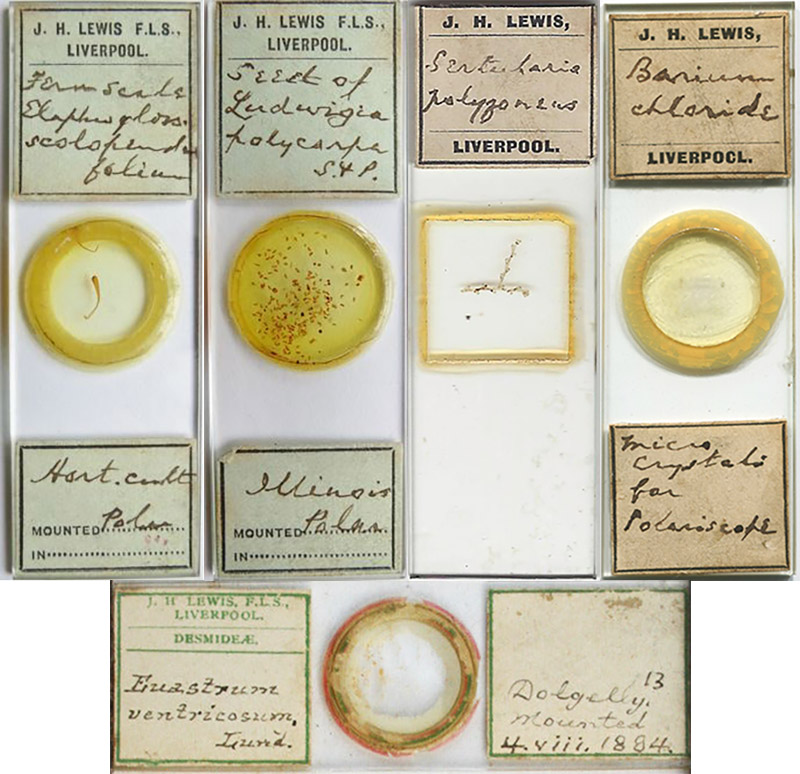

Figure 2.

J.H. Lewis’ advertisements from “Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip”, 1882-1890. His prime scientific interest prior to that time was botany. He appears to have first mentioned microscopical items in 1882, when he requested to receive microscope slides. Lenses were requested in 1885, then a high-quality microscope in 1886. Lewis’ extensive herbarium was offered up for exchange in 1886, suggesting a waned interest in plant collecting. Slides that were presumably prepared by Lewis were offered in exchange during the later 1880s. By 1890, Lewis appears to have been selling off his slide collection.

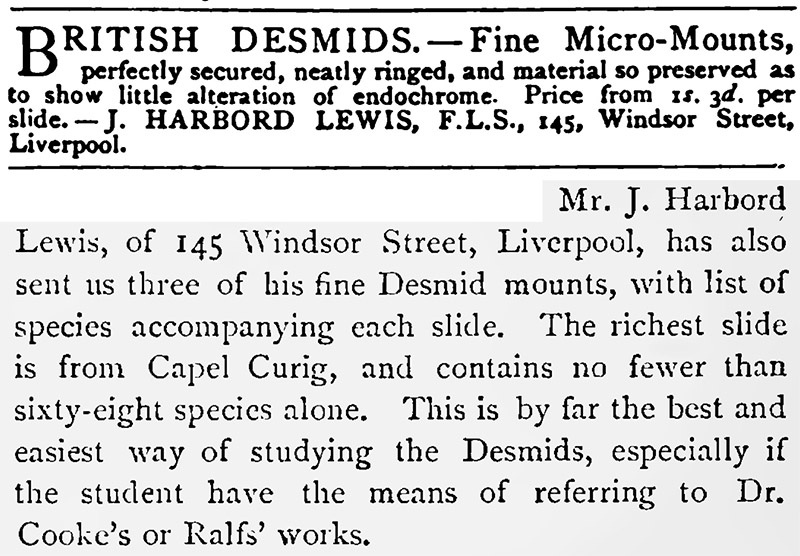

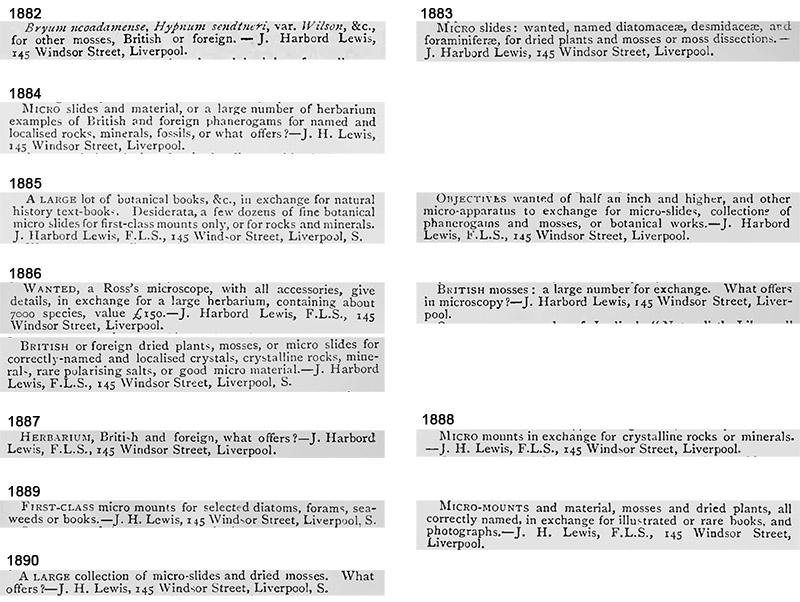

Figure 3.

An 1886 advertisement for Lewis’ microscope slides of desmids, and an editorial description of those slides, both from “Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip”.

John Harbord Lewis was born during the winter of 1848, in the West Derby section of Liverpool, England. His father, Thomas, was a partner in a shoe and boot manufacturing business. The partner, Edward Thomas, was three years older than Thomas, and the two were probably brothers. The 1851 census recorded that the T. & E. Lewis company employed “6 men”, and the 1861 census recorded employment of “18 hands”. The Lewis family lived at the business address, and did not employ domestic servants. It appears to have been a fairly modest enterprise.

As a teenager, John developed an interest in botany. He was a member of the London Botanical Exchange Club by the time he was 18. He was using custom-made labels for his collection by 1869, when he was 20 years old (Figure 4).

His mother, Ann, died in 1870, at the age of only 47. The 1871 census recorded that father Thomas, John, his sister Mary, and a widowed aunt lived at the shoe factory at 180 Mill Street, Toxteth Park, Liverpool. John was working as a commercial clerk, presumably outside of the factory.

That year, John Hooker of the Royal Gardens at Kew was searching for a Second Assistant to the Herbarium and Library. In letters, Hooker lamented that none of the current workers at the Gardens wanted the job, due to the position requiring the applicant take an onerous Civil Service examination, and “Moreover as the appointment is a poorly paid one (60£ rising to 100£), it can only be regarded as a means of improvement, or a step to promotion to botanical appointments of which there is no reasonably near prospect in the Civil Service”. Hooker further wrote, “Under these circumstances I sought elsewhere for candidates, and after several weeks inquiry, found Mr. J. Harbord Lewis, who has been a correspondent of the Herbarium, and has collected living plants for the garden, and who possesses the essential qualifications that cannot be tested by a competitive system, and whom I therefore, in my letter of 2nd September, recommended should be temporarily appointed, and only confirmed on his satisfying the Civil Service Commissioners in respect of his other qualifications”. Lewis’ interest in the position suggests that either the prospect of working with Hooker at Kew was worth the low pay, or that the family was not in very good financial shape. In the end, however, the bureaucracy changed the hiring rules to eliminate the Civil Service exam, and a London gardener was hired instead. John remained in Liverpool.

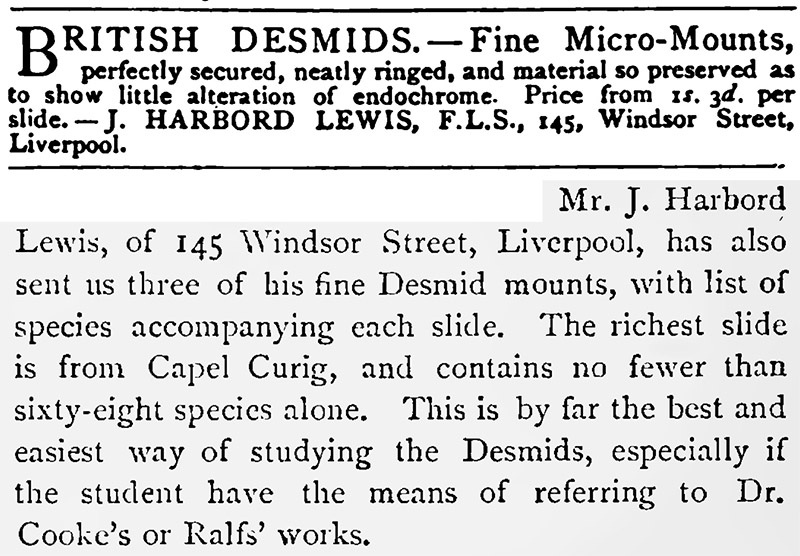

Lewis was elected to membership the Linnean Society on June 18, 1874. That year he published a proposal to sell sets of 20 different British Rubus plants (Figure 4). During 1874 and for several years afterward, he published requests to exchange plant specimens with other collectors.

Edward Lewis died in May, 1876. The T. & E. Lewis shoemaking business then became Thomas Lewis & Son, as John joined as a partner.

John Lewis married in 1879, to Jemima Bland Johnson. Their first child died in 1880, at 5 weeks of age. Two later children survived infancy, a boy and a girl.

The Lewis family occupied 145 Windsor Street, which was also a business address of Lewis & Son. Finances appear to have been a bit better for the shoe business partners by now, as John and Jemima had a live-in domestic servant at the time of the 1881 census.

Exchange advertisements suggest that Lewis had acquired a strong interest in microscopy by 1883, when he advertised to exchange his plant specimens for prepared microscope slides (Figure 2). He joined the Liverpool Microscopical Society in 1884. The 1885 International Scientists' Directory listed Lewis as interested in botany and microscopical objects. Slides of desmids were offered for sale in 1886 (Figure 3). “A large collection of micro-slides”, was offered for sale in 1890 (Figure 2). He appears to have ceased selling microscope slides around that time. This information suggests that J.H. Lewis was an active supplier of microscope slides from about 1883 until around 1890.

John, his family, and a servant lived at 145 Windsor Street, Liverpool, at the time of the 1891 census. As noted above, this was one of the partnership’s business sites. Father Thomas and a servant lived at the other business site, 180 Mill Street. The Thomas Lewis & Son shoe- and boot-making business appears to have gone out of business shortly after that time. They are not listed in the 1894 Kelly’s Directory of Liverpool. The 1901 census listed Thomas as retired. John was an “insurance agent” and “worker” (instead of “employer”), living at 48 Alt Street, Toxteth Park, Liverpool. John and Jemima’s 15 year-old daughter, Eleanor, died in February, 1902. John Harbord Lewis died in June, 1906, when 57 years old. Jemima died not long afterward, in 1913, also aged 57.

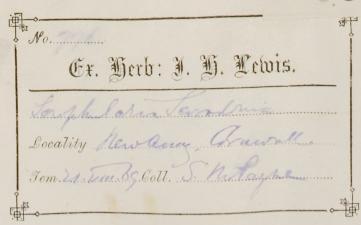

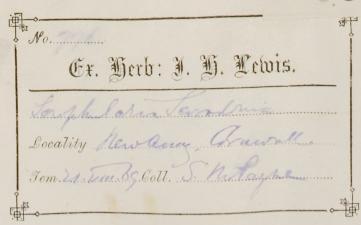

Figure 4.

Label from the herbarium of John Harbord Lewis, 1869. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from http://herbariaunited.org/collector/2694/.

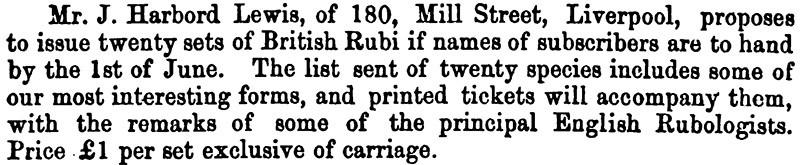

Figure 5.

An 1876 announcement of J.H. Lewis’ intention to sell sets of examples of plants from the genus Rubus. Prior to his keenness for microscopy, Lewis was an avid amateur collector of botanical specimens.

Figure 6.

Two examples of specimens that were once in J.H. Lewis’ herbarium. Left, Caltha palustris, collected by Lewis in 1873, then acquired by Charles Bailey in 1895. Right, Consolida regalis collected by Jean Piquet in 1864, then acquired by Lewis, and later acquired by Bailey. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from http://herbariaunited.org/specimen/231114/ and http://herbariaunited.org/specimen/215060

Resources

The American Monthly Microscopical Journal (1886) “Desmid Material Wanted - We are in receipt of a letter from Mr. J. Harbord Lewis, F.L.S., of 145 Windsor street, Liverpool, England, dated 25th October, 1886. The letter is evidently intended as a personal communication to Prof. R. Hitchcock, the writer not knowing of his absence from this country. The writer encloses an advertisement of fine mounts of British desmids, which he offers for sale at prices varying from 4s. to 1s. 3d. He is anxious to obtain American desmid and filamentous fresh-water alga material, and offers to make suitable return in slides. 'Materials may be in the rough, just as gathered; and it is advisable to have exact locality, date, and the preservative used, for sake of reference, in case anything good turns up.' Since the offer of Mr. Lewis was intended for Mr. Hitchcock, who has studied these plants very fully, we do not wish our readers to understand that everyone is requested to exchange on the terms mentioned, but we suggest that any desmid collector who desires to improve this opportunity confer for himself with Mr. Lewis”, Vol. 7, page 214

The American Monthly Microscopical Journal (1887) “Microscopical Societies: Washington, D.C. … The 60th regular meeting was given up to an exhibition of slides, principally a lot recently imported from Moller by various members of the Society. Two type-plates, one of one hundred and one of four hundred diatoms, were shown, with other slides of different kinds. … One of J. Harbord Lewis' desmid slides, containing some fifty species, was also shown.”, Vol. 8, page 116

Bracegirdle, Brian (1998) Microscopical Mounts and Mounters, Quekett Microscopical Club, London, pages 62 and 152, and Plate 24-G and 24-H

Burial records of Toxteth Park Cemetery (accessed August, 2017) http://www.toxtethparkcemetery.co.uk

The Commercial Directory of Liverpool, and Shipping Guide (1875) “Lewis T. & E., bootmakers, 180 Mill street S”, page 85

England census, birth, marriage, death, and other records, accessed through ancestry.com

A. Green and Co.'s Directory for Liverpool and Birkenhead (1870) “Lewis, T. & E. boot and shoe manufacturers, 180, Mill street”, page 296

Herbaria United (accessed August, 2017) http://herbariaunited.org

Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip (1874) Exchange offer from J. Harbord Lewis, Vol. 9, page 284

Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip (1875) Exchange offers from J. Harbord Lewis, Vol. 11, pages 120, 240, and 283

Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip (1882) Exchange offer from J. Harbord Lewis, Vol. 18, page 144

Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip (1883) Exchange offer from J. Harbord Lewis, Vol. 19, page 120

Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip (1884) Exchange offer from J. Harbord Lewis, Vol. 20, page 264

Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip (1885) Exchange offers from J. Harbord Lewis, Vol. 21, pages 24, 72, and 168

Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip (1886) Advertisement from J. Harbord Lewis, Vol. 22, page xciv

Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip (1887) Exchange offers from J. Harbord Lewis, Vol. 23, pages 48, and 168

Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip (1889) Exchange offers from J. Harbord Lewis, Vol. 25, pages vi and xiv

Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip (1890) Exchange offers from J. Harbord Lewis, Vol. 26, page 95

The International Scientists' Directory (1882) “Lewis, J. H., 145 Windsor Street, Liverpool. Bot.”, SE Cassino, Boston, page 271

The International Scientists' Directory (1885) “Lewis, J. Harbord, F.L.S., 145 Windsor St., Liverpool. Crypt. Bot., Mic. objects. C. Ex.”, SE Cassino, Boston, page 228

The International Scientists' Directory (1888) “Lewis, J. Harbord, F.L.S., 145 Windsor St., Liverpool, S. Desmids. C. Ex.”, SE Cassino, Boston, page 237

The Journal of Botany, British and Foreign (1874) Announcement of J.H. Lewis’ intent to issue a collection of Rubus specimens, Vol. 12, page 160

ather dying when Carl was young, Carl was fascinated Kelly's Directory of the Leather Trades (1880) “Lewis Thomas & Son, 145 Windsor st. & 180 Mill st. Toxteth park, Liverpool”, page 281

Kelly's Directory of the Leather Trades (1885) “Lewis Thomas & Son, 145 & 147 Windsor st. & 180 Mill st. Toxteth pk.”, page 103

Kelly’s Directory of Liverpool and Suburbs (1894)

London Botanical Exchange Club, Report of the Curators (1867) “Members … Lewis, J. Harlow (sic), 180, Mill Street, Liverpool”, page 4

Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London (1874) Minutes of the June 18, 1874 meeting, “E. Birchall, Esq., James Leathem, M.D., and J. Harbord Lewis, Esq., were elected Fellows”, page 39

Report of the Liverpool Microscopical Society (1887) Members “1884 Lewis, J. Harbord, F.L.S. 145, Windsor-street”

Sessional Papers Printed by the Order of the House of Lords (1871) Letters of J.D. Hooker in regards to J.H. Lewis, pages 125 and 129