Figure 1. Advertisement for Cornelius Poulton, from Quekett’s 2nd edition of “A Practical Treatise on the Use of the Microscope” (1852)

Cornelius Poulton, 1814 – 1854

by Brian Stevenson and Howard Lynk

last updated April, 2013

John Quekett published his classic A Practical Treatise on the Use of the Microscope: Including the Different Methods of Preparing and Examining Animal, Vegetable, and Mineral Structures in 1848, with revised editions published in 1852 and 1855. These books make fascinating reading for students of Victorian era microscopy. Particularly relevant to this series of biographies, Quekett named several professional microscope slide preparers with whom he had dealt favorably. The 1848 edition mentioned only Charles M. Topping (page 366), with whom Quekett had a long-term friendship and who is perhaps the most famous of all the early English slide preparers. In the 1852 edition (page 399), Quekett again named Topping, along with “ Mr. Darker, of No. 9, Paradise Street, Lambeth – Mr. J. T. Norman, of No. 10, Fountain Place, City Road – Mr. J. W. Bond, of No. 1. Emma Street, Ann’s Place, Hackney Road – and Mr. C. H. Poulton, of Southern Hill, Reading.”. William H. Darker was well known in his time for high quality thin-sectioned mineral, wood and bone mounts, although most were not labeled with his name and are not always recognized today. James W. Bond was a major supplier of prepared slides through the early- to mid-1800s, many of which where labeled with his initials, JWB. Charles M. Topping and John T. Norman remain famous to this day, due in part to their well-labeled slides. Prior to our studies, almost nothing was known about Cornelius Poulton other than his brief mention by Quekett. Particularly intriguing, Quekett’s 1855 edition again mentioned Topping, Darker, Norman and Bond, but omitted Poulton (page 430). In this essay, we describe some of Poulton’s work, and present a biography of his short life.

In addition to the “tip of the hat” given by Quekett in 1852, Cornelius Poulton bought an advertisement in the back of the book (Figure 1). Whether the advertisement prompted Quekett to include Poulton among his list of preferred slide mounters, or vice versa, is unknown. However, Quekett knew of Poulton’s work by 1850, at the latest (see below).

Figure 1. Advertisement for Cornelius Poulton, from Quekett’s 2nd edition of “A Practical Treatise on the Use of the

Microscope” (1852)

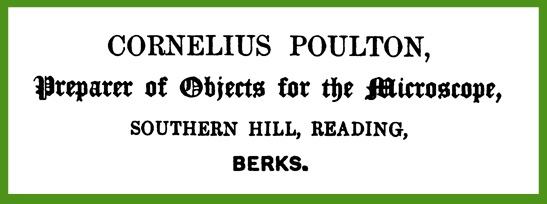

We know of only two microscope slides that bear Cornelius Poulton’s name (Figure 2). The reverse sides of each carry a label with Poulton’s name and address. The fronts are a simple geometric pattern of gold on pale green paper. Descriptions of the specimens are written in what is presumably Poulton’s hand.

Figure 2. Front and back views of two microscope

slides labeled with Cornelius Poulton’s name.

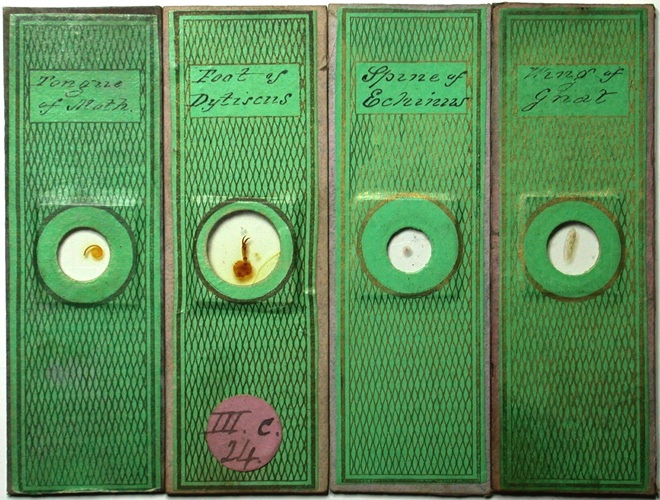

Unnamed slides with the paper style and handwriting shown in Figure 2 are somewhat common. Other slides with the same paper, but a more flowing style to the capital letters, are also commonly found in antique slide collections. Numerous similarities between other written letters make it highly likely that all these slides were labeled by the same person (Figure 3).

Figure 3. A selection of microscope slides with the same paper style as those shown in Figure 2. The handwriting style of the two leftmost slides is identical to that of the slides in Figure 2. Although the two rightmost slides have distinct styles for most capital letters, the lowercase letters on all four slides are nearly identical in style. In particular, compare the word ‘of’ and the capital letter ‘M’ in these slides and those shown in Figures 2 and 4. These similarities strongly suggest that all four of these slides were also made by Cornelius Poulton.

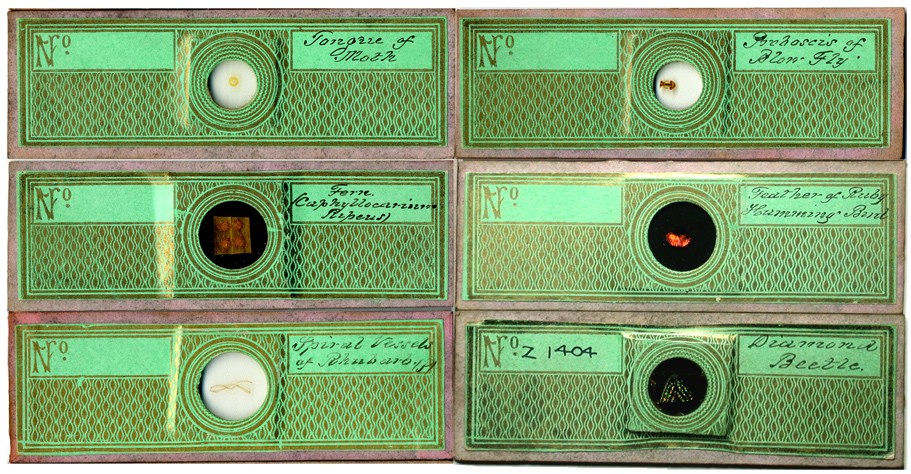

Using the handwriting styles of slides such as shown in Figures 2 and 3 as guides, we consider it highly probable that microscope slides using another style of paper were also produced by Cornelius Poulton (Figure 4). Additional examples of Cornelius Poulton’s slides, and other paper styles, may be seen at Howard Lynk’s illustrated web site of Victorian Microscope Slides

Figure 4. A selection of microscope slides with the same handwriting style as the two rightmost slides shown in Figure 3, with a different style of paper wrappers. Compare the “Tongue of Moth” with the leftmost slide in Figure 3: except for the capital ‘T’, the handwriting is identical.

Cornelius Poulton was the eldest of six children of Cornelius and Mary Poulton, born 17 October, 1814. Cornelius, senior, was a linen draper in Reading. The youngest son, William, was a noted architect and the father of Edward Bagnall Poulton, a professor of zoology at Oxford. There is a wealth of information on William and Edward available on the web.

Our Cornelius married Mary Wright in late 1840, in Basingstoke, Hampshire. The young couple then set up in Duke St., Saint Lawrence, Reading, Berkshire. The 1841 England census records Cornelius as being a chemist (pharmacist, to Americans).

Two mentions of Cornelius Poulton appeared in books published during 1850, both indicating that he was deeply involved with preparing microscopical specimens by that time. In the first, Gideon Mantell’s Notice of the Remains of the Dinornis, and Other Birds, and of Fossils and Rock-Specimens, Recently Collected by Walter Mantell, Esq. from the Middle Island of New Zealand, a footnote on pages 332-333 reads “For the most beautiful preparations of these infusorial earths, and especially for a selection of the most delicate organisms mounted separately, I am indebted to Mr. C. Poulton, of Southern Hill, Reading, whose skill in this department of microscopic manipulation is well known.” Poulton evidently prepared and mounted diatoms, foraminifera and other microscopic objects from soils brought from New Zealand for Mantell’s benefit.

In the second

instance from 1850, Cornelius Poulton was acknowledged for his donation of a

prepared slide to the Royal College of Surgeons Museum. Page 180 of John Quekett’s Descriptive

and Illustrated Catalogue of the Histological Series Contained in the Museum of

the Royal College of Surgeons of England, Volume 1, describes specimen Ap6 as:

“A

portion of the horny skeleton of a Sponge allied to the genus Verongia, having

a coarse network of large fibres, in many of which may be discerned either a

single large spiculum, or others of smaller size arranged in bundles, as shown

in Plate X. fig. 10a. The spicula

are not present in every fibre, but principally in those that are of large

size, and more or less flattened. Presented by Mr. C. Poulton.” This slide is still part of the

Museum’s collection, although currently not on public display.

By 1851, Poulton was apparently producing large quantities of microscope slides, describing himself for that year’s census as a “Mounter of Microscopic Objects”. He seems to have been doing fairly well for himself, as he and Mary employed a 13 year old girl as a live-in house servant. The original census record includes the phrase ’10-9 others’, the meaning of which is uncertain. It may indicate that Poulton employed several workers. However, the handwriting is not that of the census taker. A similar note appears elsewhere in this census book, in the same handwriting. The notes may have been added to the record book at a later time, but why they are there is not known.

1851 was the year of the Great Exhibition in London. As did many other professional microscopists, Poulton displayed his work there. His was exhibit 252 in Class 10 (Philosophical, Musical, Horological and Surgical Instruments), described in the Official Catalogue as “Objects prepared for the microscope, with drawings by M.S. Legg.” The artist was presumably the same M.S. Legg who was a member and officer of the Microscopical Society of London, as were also J. Quekett and many other important early microscopists. This suggests that good connections existed between Poulton and the “powers that be” of English microscopy. Notwithstanding, a review of the microscopy exhibits published in Medical Times glowed about the displays of Charles Topping and Alexander Hett, but had this to say about Poulton: “The remaining collections of Mr. Poulton (252), Mr. Hudson (256), and Mr. Stark (284), possess little or no interest; they are most of them common objects, which serve rather as toys for amusement than for instruction, and are by no means so well mounted as those we have already noticed.” The anonymous reviewer had this additional snipe regarding Stark: “Mr. Stark's collection is chiefly remarkable for the use of rings of gutta percha for cells, instead of glass rings usually employed. This idea, although, perhaps novel in Edinburgh, was tried and abandoned years ago by Mr. Quekett, who found that the gutta percha could not be made to adhere with certainty to the glass.”

That year, Poulton exhibited slides at the annual meeting of the Microscopical Society of London (which became the Royal Microscopical Society in 1866). He was noted by Fredrick Hudson as displaying “some good objects”, including mounted spiracles of a breeze fly.

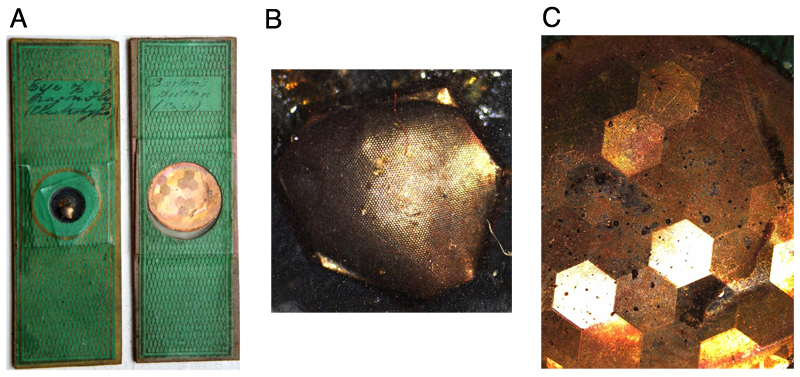

Also during 1851, Poulton was reported to produce high quality electro-cast engravings for viewing under the microscope. In Elements of Electro-Metallurgy, Alfred Smee wrote, “Mr. Poulton has lately sent me an electro cast of the eye of a dragon fly, which under the microscope exhibits perfectly all the facets common to a compound eye. This must be regarded as a very remarkable application to this ingenious manipulation.” and “I have an electro cast of a Barton’s button in copper, which was given to me by Mr. Poulton, one of our preparers of microscopic objects, of whom, I believe, they can be purchased”. Surviving examples of these slides are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. (A) Poulton slides of electro-engravings on metal. (B) Magnified detail of cast eye of dragonfly. (C) Magnified detail of Barton’s button. These were metal buttons with various types of diffraction patterns engraved on their top surface. Made by John Barton, these samples were drawn using his own ruling engine to produce a rainbow of colours due to the interference of light when it strikes the engravings. Ornamented pieces with diffraction patterns ruled upon them became popular with the public during the 19th century.

The diversity and significance of Cornelius Poulton’s work are also evident from his contributions to the study of diatoms. The Reverend William Smith, in his 1853 and 1856 editions of A Synopsis of the British Diatomaceae, acknowledged Poulton for descriptions of Biddulphia pulchella, Eupodiscus argus and Pleurosigma spencerii. Gideon Mantell wrote in his 1854 Medals of Creation that “As both the recent and fossil frustules of Diatomaceae are beautiful objects for the microscope and polariscope, they are in much request. Specimens mounted on glass slides may be had of Mr. Topping, and Mr. Poulton” and “Mr. Poulton has specimens of the shells, and the bodies of the animals deprived of the shell, mounted for the microscope”. Curiously, a list of suppliers in Mantell’s 1854 book provided an address for Poulton of Wooburn, Buckinghamshire, although all other records of Poulton place his home in Reading, Berkshire.

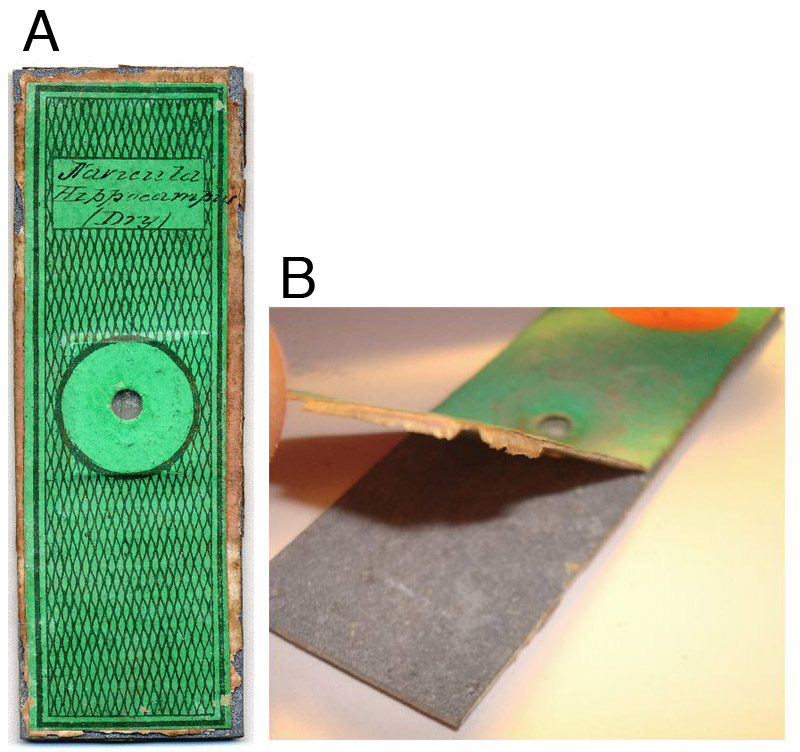

Diatom mounts by Cornelius Poulton are relatively uncommon. Figure 6 illustrates a slide of Navicula hippocampus diatoms that were mounted dry between two thin glass slips, and then affixed to a metal slide. Other mounters of the time, such as C.M. Topping, similarly mounted diatoms between thin glass, but generally attached the glass to wooden slides. The metal of the Poulton slide has oxidized over the years, and the labels have become loose (Figure 6B). If this was Poulton’s standard method for mounting diatoms, their tendency of fall apart over time may explain the paucity of such slides today.

Figure 6. (A) A rare diatom slide by Cornelius Poulton, being a dry mount of Navicula hippocampus. (B) The metal used as the base of the slide has oxidized over the years, and the labels have partly detached.

Figure 7. Two more rarities. Microscope slides labeled by the famed diatomist Reverend William Smith, with either the specimens or mounted slides having been provided to him by Cornelius Poulton.

Cornelius Poulton died at the age of 39 on 20 July, 1854 at his home in Reading. The listed cause of death was peritonitis, an infection of the peritoneum (abdominal cavity). The origin of the peritonitis was not recorded, but may have resulted from a burst appendix. In the pre-antibiotic era, such infections were highly fatal. The death record noted Poulton’s occupation as “photographic artist”, suggesting that he also had a photography business. Cornelius’ wife, Mary, probably died in 1862, also in Reading. They do not appear to have had any children.

In conclusion, Cornelius Poulton was a well-regarded preparer of microscope slides during the mid-1800s. Judging from the large numbers of his slides to be found today, he was probably a significant supplier in his time. Other than the two examples illustrated in Figure 2, we are not aware of any extant microscope slides that bear his name. We would be extremely grateful for information on any other named slides.

Acknowledgment:

Many thanks to Stephen Parker for generously providing images of Poulton’s electro-engraving slides.

Resources:

Davidson, Brian (2007) Topping Slides 1840-50, Quekett Journal of Microscopy, vol. 40, pages 375-388.

Death record for Cornelius Poulton (1854)

Descendants of Silver Poulton. http://www.uspoultons.fsworld.co.uk/cookham/pafg07.htm

England vital statistics, accessed through www.ancestry.co.uk

Mantell, Gideon Algernon (1850) Notice of the Remains of the Dinornis, and Other Birds, and of Fossils and Rock-Specimens, Recently Collected by Walter Mantell, Esq. from the Middle Island of New Zealand, published by the Geological Society of London

Mantell, Gideon Algernon (1854) The Medals of Creation: Or, First Lessons in Geology and the Study of Organic Remains, Edition 2, published by H. G. Bohn. Reprinted in 1980 by Ayer. Pages 100 and 348

Medical Times (1851) The Great Exhibition, vol. 24, pages 71-72, published by J. A. Carfrae

Microscopical Society of London (1847) Report of the Seventh Anniversary of the Microscopical Society of London, printed by E. Newman (contains information on M.S. Legg)

Quekett, John Thomas (1848) A Practical Treatise on the Use of the Microscope: Including the Different Methods of Preparing and Examining Animal, Vegetable, and Mineral Structures, 1st Edition, published by H. Bailliere

Quekett, John Thomas (1852) A Practical Treatise on the Use of the Microscope: Including the Different Methods of Preparing and Examining Animal, Vegetable, and Mineral Structures, 2nd Edition, published by H. Bailliere

Quekett, John Thomas (1855) A Practical Treatise on the Use of the Microscope: Including the Different Methods of Preparing and Examining Animal, Vegetable, and Mineral Structures, 3rd Edition, published by H. Bailliere

Quekett, John (1850) Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue of the Histological Series Contained in the Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, Volume 1, printed by R and JE Taylor

Official Catalogue of the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations (1851) published by Spicer Brothers (Poulton entry on page 63)

Rootsweb Poulton-L archives, 24 Feb., 2007. http://archiver.rootsweb.ancestry.com/th/read/POULTON/2007-02/1172288573

Royal College of Surgeons of England Museum catalog information on item Ap6, a specimen of sponge skeleton donated by Cornelius Poulton. http://surgicat.rcseng.ac.uk

Smee, Alfred (1852) Elements of Electro-Metallurgy, 1st American edition, from the 3rd London edition (published in 1851), J. Wiley, New York. Pages 280 and 288

Smith, William (1853) A Synopsis of the British Diatomaceae, printed for Smith & Beck by J. Van Voorst. Pages 24 and 68-69

Smith, William (1856) A Synopsis of the British Diatomaceae, printed for Smith & Beck by J. Van Voorst. Page 48

Turner, Gerald L. (1994) Frederick Thomas Hudson’s microscopical diary, Quekett Journal of Microscopy, Vol. 37, pages 191-206