William Rushby, ca. 1745 - ca. 1810

and his association with the manufacture of

“folding-pin” naturalist’s simple microscopes

by Brian Stevenson

last updated September, 2020

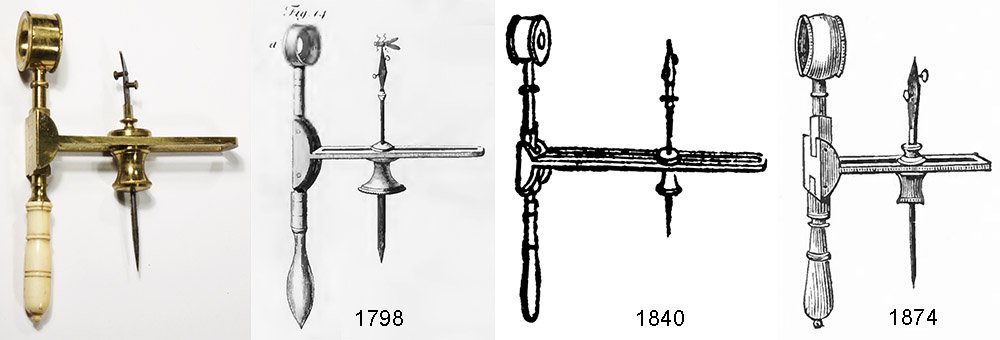

Small, folding, hand-held simple microscopes are quite popular among antique collectors (Figures 1-2). When in use, they are 2.5 - 3 inches / 6-7 cm from the top of the lens to the tip of the handle. The handle and lens-holder fold on hinges into a flat shape (Figures 3-4). Many were originally sold with rectangular cardboard boxes (Figures 3-5). Two main types of naturalist’s simple microscopes were produced.

One type has a specimen holder that consists of only a brass pin (Figure 1). For storage, the tip of the pin folds flat (Figures 3-4). One “folding-pin” microscope has a carry case that is dated 1787 (Figure 10). That, plus investigations of historical records, indicate that “folding-pin” microscopes were made during the late 1700s, and that their production likely ended around 1800.

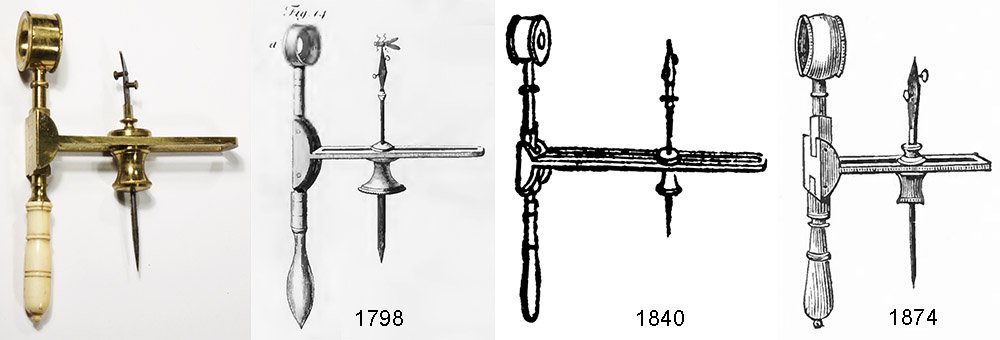

Two major drawbacks of the “folding-pin” type - the brass spike is easily bent or dulled, and specimens must be impaled - were remedied by development of the “forceps” type, which has a specimen holder with a forceps on one end and a sharp steel spike on the other (Figure 2). This form was first illustrated in the 1798 edition of George Adams Jr.’s Essays on the Microscope and was manufactured by W. & S. Jones. For that reason, the “forceps” type is frequently called a “Jones’ naturalist” or “Jones’ botanical” microscope, although it was made by numerous other manufacturers throughout the nineteenth century (Figure 2). These are far more commonly encountered today, reflective of their having been manufactured over a span of roughly 100 years.

Figure 1.

A “folding-pin” type of naturalist’s simple microscope. Specimens must be impaled on the brass pin for viewing, with focus by sliding the pin mount toward/away from the simple lens. The two parts of the pin mount are connected by a screw, which can be loosened to move the mount or tightened to hold it in position. For storage, the pin folds down, and the lens and handle fold together (see Figure 3). The handle is made from bone. Images from a private collection.

Figure 2.

An improvement on the “folding-pin” microscope, the “forceps” type has a specimen-holder with hardened-steel forceps on one end and a sharp steel spike on the other. The steel specimen holder slides in the brass fitting, can be inverted depending upon use, and is removed for storage. This type of naturalist’s simple microscope was first illustrated in the 1798 edition of George Adams Jr.’s “Essays on the Microscope”, which was published by W. & S. Jones, and is often called the “Jones’ naturalist” or “Jones’ botanical” microscope. The type was also illustrated in catalogues throughout the nineteenth century, including those of Edward Palmer (1840) and James Queen & Co. (1874). Microscope image from a private collection.

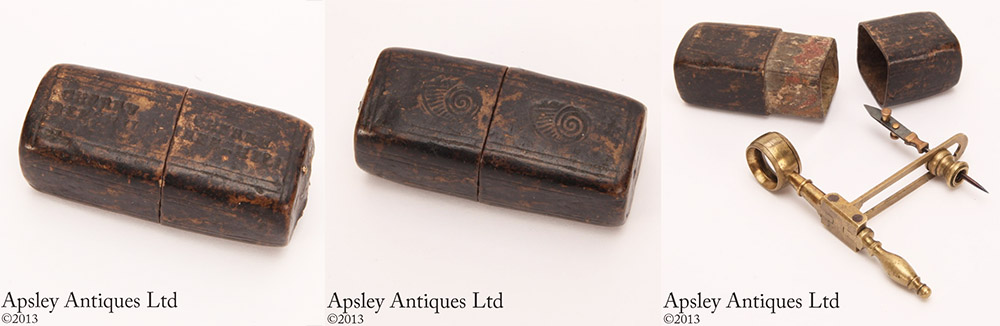

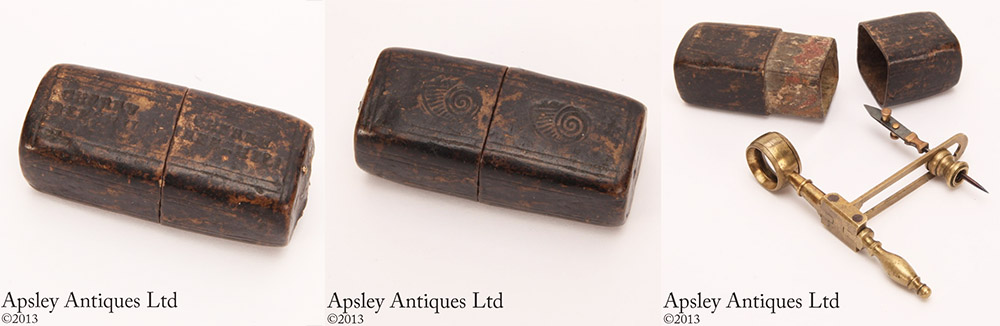

Records of museum holdings and past auctions revealed 5 “pin-mounted” simple microscopes with cases that are embossed with “W. Rushby” and “Cherry Tree Hill” (Figure 3). Several others have identically-sized cases that are stamped with only “Cherry Tree Hill” or motifs found on Rushby-signed cases (Figures 4-5). That large number of examples indicate that Rushby was involved with the microscopes’ manufacture or distribution.

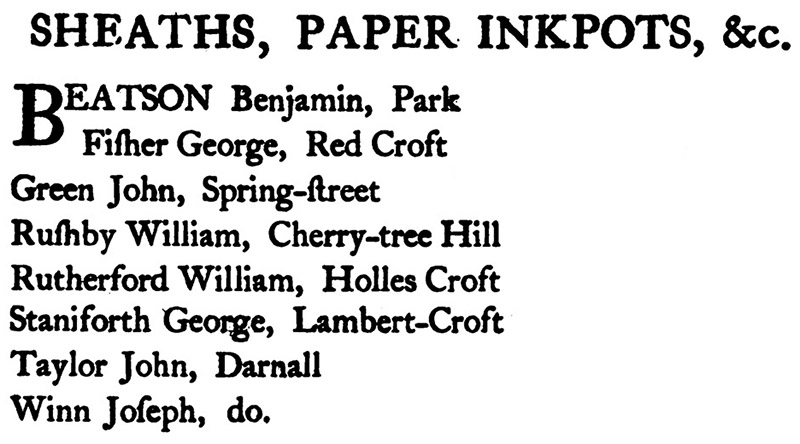

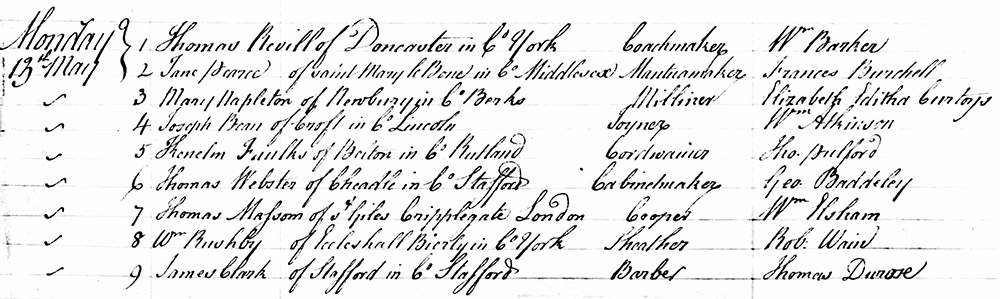

William Rushby was a manufacturer of “Sheaths, Paper Inkpots, &c.”, working in Cherry Tree Hill, Yorkshire in the mid-/late-1700s (Figure 6). Cherry Tree Hill was then a village on the outskirts of Sheffield. Even in the 1700s, Sheffield was a major center for production of knives, swords, scythes, scissors, files, and other cutting implements. Rushby and a half dozen other craftsmen produced the sheaths for those instruments. William Rushby served as master to an apprentice sheath-maker in 1776, indicating that he was then established in the craft and thus at least 25-30 years old (Figure 7). Therefore, Rushby was born, at the latest, in 1745-1750. An average lifespan would place his death around 1810. Tax records indicate that a William Rushby lived in the Cherry Tree Hill area until at least 1802.

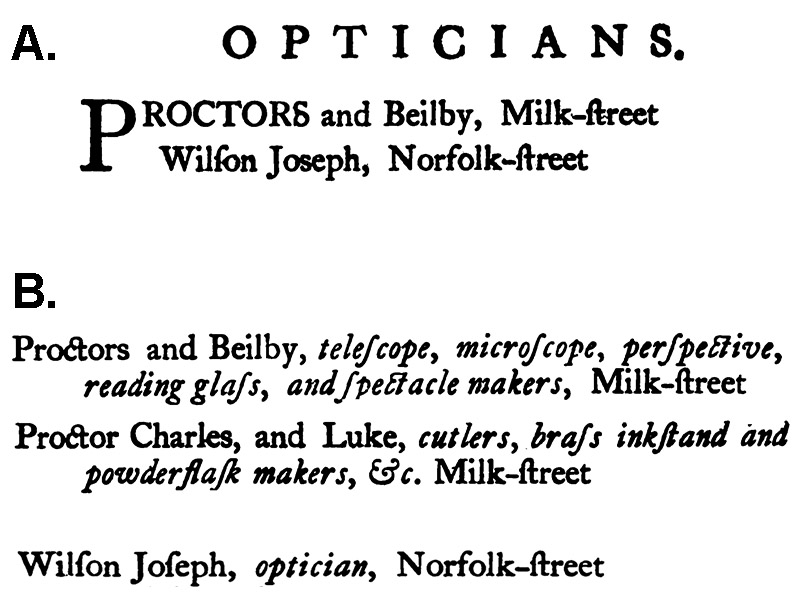

However, William Rushby was not a worker of brass or glass (indeed, the 1787 directory of Sheffield has a separate listing for makers of brass inkpots). While Sheffield had numerous metalworkers, some of whom worked in brass, the vast majority stamped their works with distinctive hallmarks, and, to the best of my knowledge, no “folding-pin” type microscope has a hallmark. A more probable source would be Proctors & Beilby (later Proctor & Beilby, then G. & W. Proctor), who were “telescope, microscope, perspective, reading glass, and spectacle makers” and “cutlers, brass inkstand and powderflask makers”. That firm employed workers who were experienced in lens grinding, brasswork, and, being cutlers, shaping of bone for handles (see below). Also of note, John Priston Cutts (1787-1858), later a well-known manufacturer of microscopes, learned his trade as an apprentice with Proctor & Beilby.

It is reasonable to conclude that many of the “folding-pin” type simple microscopes like those shown in Figures 1, 3, and 4 were manufactured in Sheffield during the late 1700s (and possibly into the very early 1800s). Many of their cases were marked by William Rushby, suggesting that he played a role in their distribution. Other cases were evidently produced by Rushby, but without his name on them, and were presumably distributed by another source(s). Proctor and Beilby were the likely manufacturer.

Figure 3.

Three “folding-pin” simple microscopes, each of which has a cardboard carrying case embossed with “W. Rushby” and “Cherry Tree Hill”. The case of example A is also embossed with two ammonites (or snails). Two other “folding-pin” microscopes of the same pattern are known that also have Rushby cases. Images from private collections or adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from internet sale sites.

Figure 4.

The case of this “folding-pin” microscope is embossed with a large ammonite or snail on one side and a pair of simple shapes on the other. The similarities between the microscope and case with those shown in Figures 1 and 3 suggest that they were all produced by the same maker. Images from adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet sale site.

Figure 5.

A similar microscope with a handle of brass, rather than bone, with a case that is marked “Cherry Tree Hill” (twice) and stamped on the other side with a pair of ammonites. Although it currently has a forceps specimen holder, that may not be original: note the length of the specimen holder - if it is inverted so that a specimen can be impaled on the spike, the specimen will not align with the lens, and so the lens must be folded by 45 degrees or so in order to be used. “Forceps” type naturalist’s simple microscopes generally have much longer specimen holders (see Figure 2), which allow easy use of either the spike or the forceps. This example has a short specimen holder so that it will fit into the case. A standard “forceps” type holder is 1/2 inch / 1.5 cm too long to fit into a Rushby-type case. Images from adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet sale site.

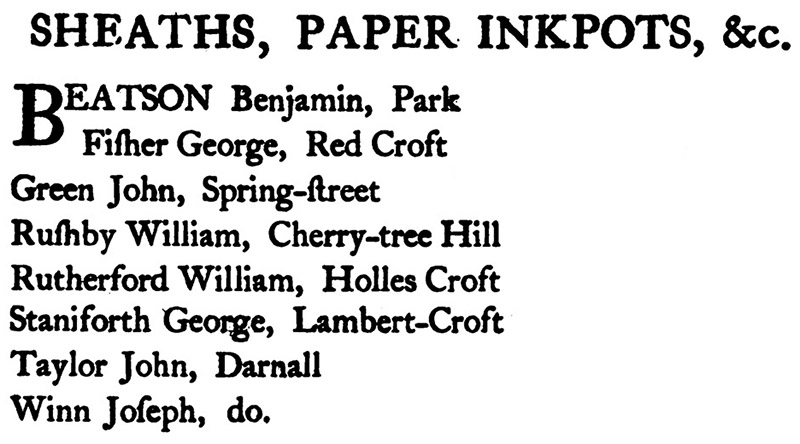

Figure 6.

From “A Directory of Sheffield”, 1787.

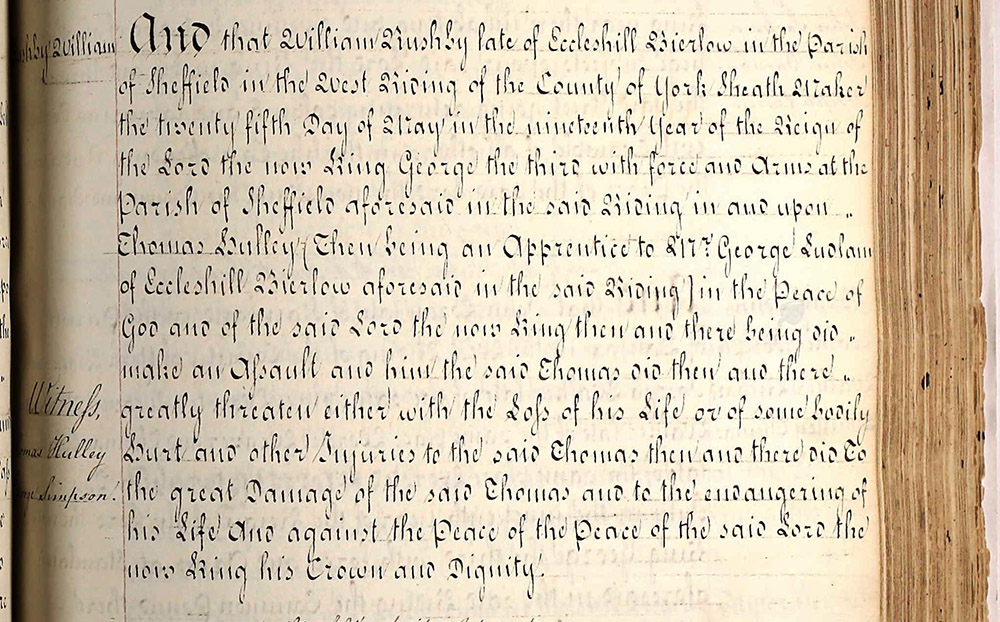

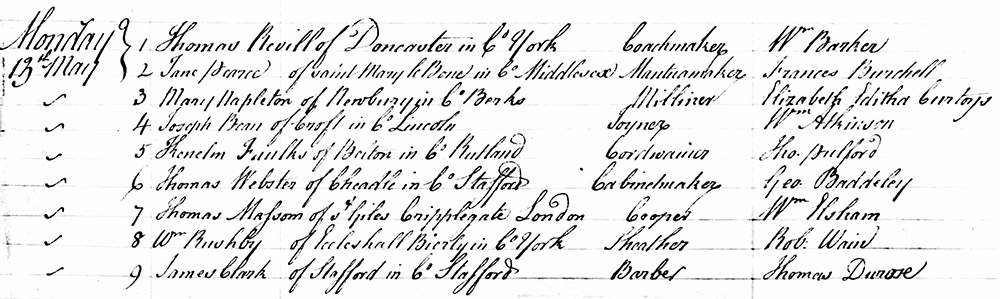

Figure 7.

On May 13, 1776, “Wm. Rushby of Eccleshall Bierly (sic) in Co. York, Sheather” took Robert Wain as his apprentice. This indicates that Rushby was an accomplished master craftsman by this date. Cherry Tree Hill is within the area known as Ecclesall Bierlow.

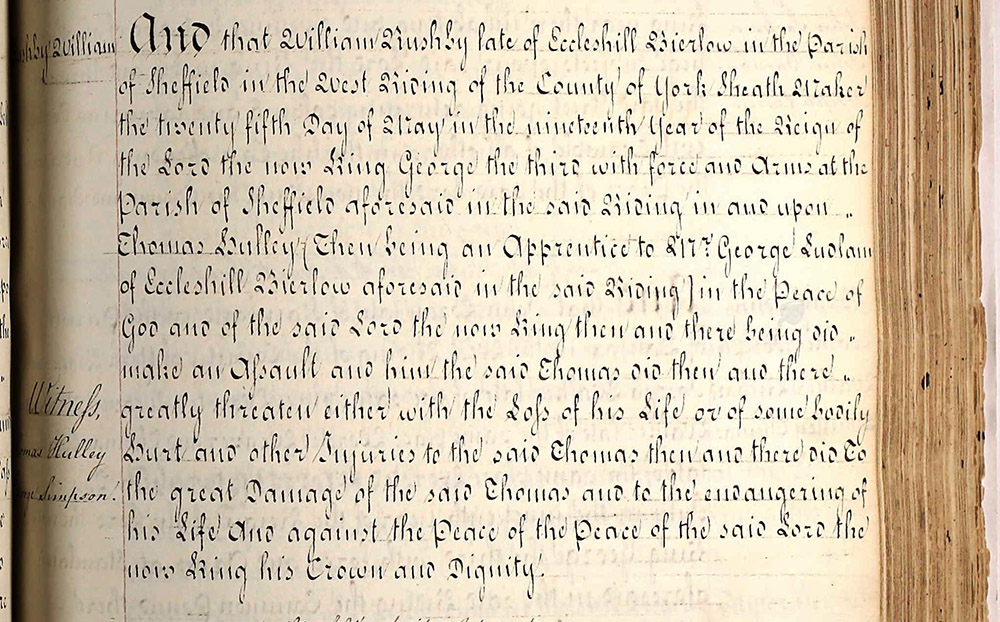

Figure 8.

The only other known record of William Rushby’s life: on August 9, 1779, “William Rushby late of Eccleshill (sic) Bierlow … Sheath Maker” was arraigned for assault on Thomas Hulley, and did “greatly threaten either with the loss of his life or of some bodily hurt and other injuries”. The outcome of his trial was not recorded.

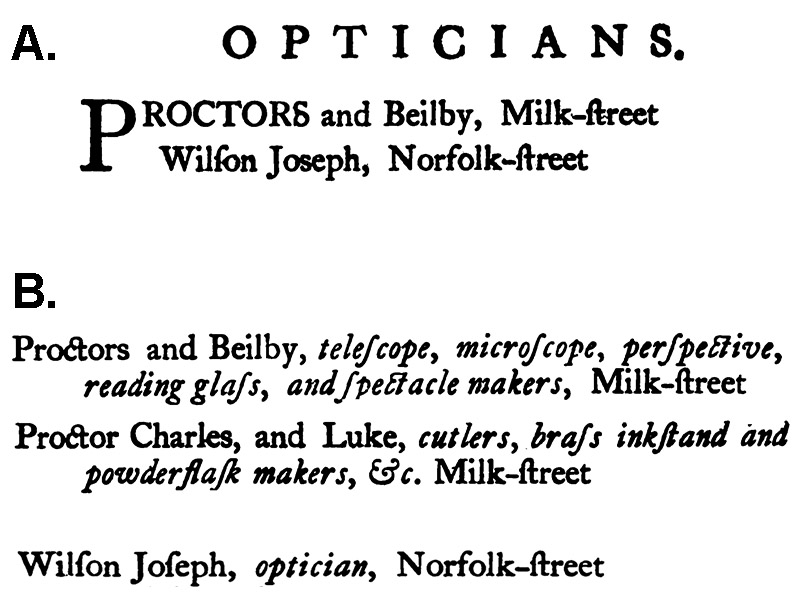

Figure 9.

Opticians’ entries from the 1787 Sheffield directory, organized by trade (A) or alphabetically (B). The firm of Proctors & Beilby consisted of brothers Charles and Luke Proctor, and Thomas Beilby, and produced a large number of products, including microscopes. The business was later known as Proctor & Beilby, and G. & W. Proctor. The town’s other optician, Joseph Wilson, appears to have made only eye glasses.

Figure 10.

A very different style of “folding-pin” microscope - compare the hinge joints with the Rushby-associated microscopes in Figures 1, 3, and 4. The lid of its box is inscribed, “The gift of Wm. Chapman Esq. 1789”, evidence that the “folding-pin” form was being produced at least 9 years before the “forceps” type was described in 1798. The date on this box is also consistent with Rushby’s involvement with producing “folding-pin” simple microscopes during the mid/late-1700s. Chapman may have been the noted civil engineer William Chapman (1749-1832). Images from a private collection.

Figure 11.

William Rushby frequently used ammonite shapes when decorating microscope cases. This is a 400 million year old Anetoceras sp., from a private collection.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Joe Zeligs and Jeff Silverman for their helpful comments.

Resources

A Directory of Sheffield, Published by Gales & Martin in 1787, Reprint (1889) Pawson & Brailsford, Sheffield

England census and other records, accessed through ancestry.com

Gardner-Medwin, David (2003) Bewick Studies: Essays in Celebration of the 250th Anniversary of the Birth of Thomas Bewick, 1753-1828, Bewick Society, page 80

London Gazette (1812) Notice of the dissolution of Proctor, Beilby & Co., page 2332

Walker, William (1864) William Chapman, M.R.I.A., Memoirs of the Distinguished Men of Science of Great Britain Living in the Years 1807-8, W. Davy & Son, London, pages 31-34