Charles Proctor, 1739 - 1808

Luke Proctor, 1743 - 1817

Thomas Beilby, 1747 - 1826

George Proctor, 1774 - after 1820

William Proctor, 1776 - after 1830

Thomas Bielby, Jr, 1781 - 1860

Proctor / C. & L. Proctor, ca. 1760s - ca. 1787

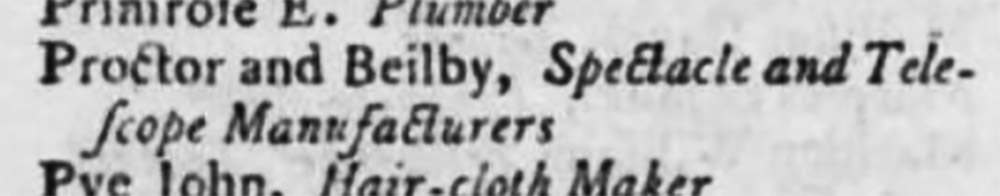

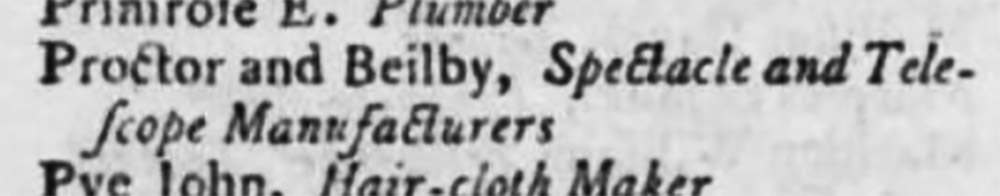

Proctors and Beilby, ca. 1780 - ca. 1787

Proctor and Beilby, ca. 1787 - 1808

Proctor, Beilby, and Company, 1808 - 1812

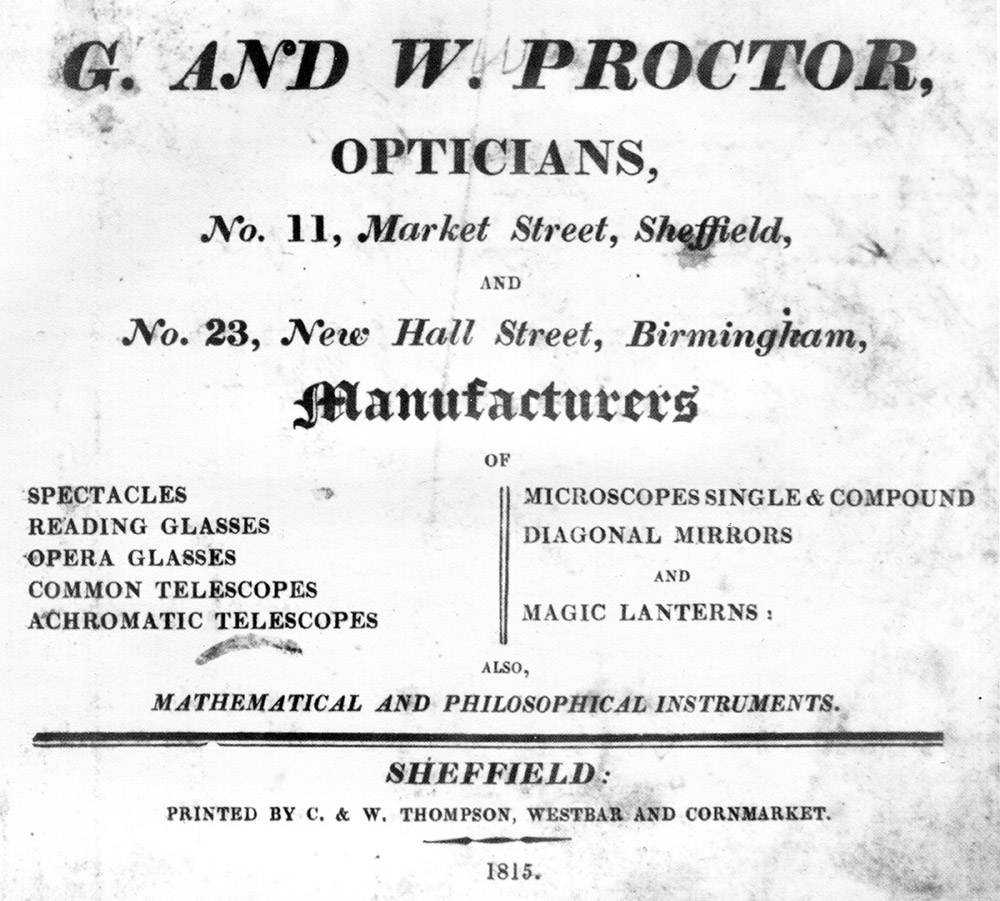

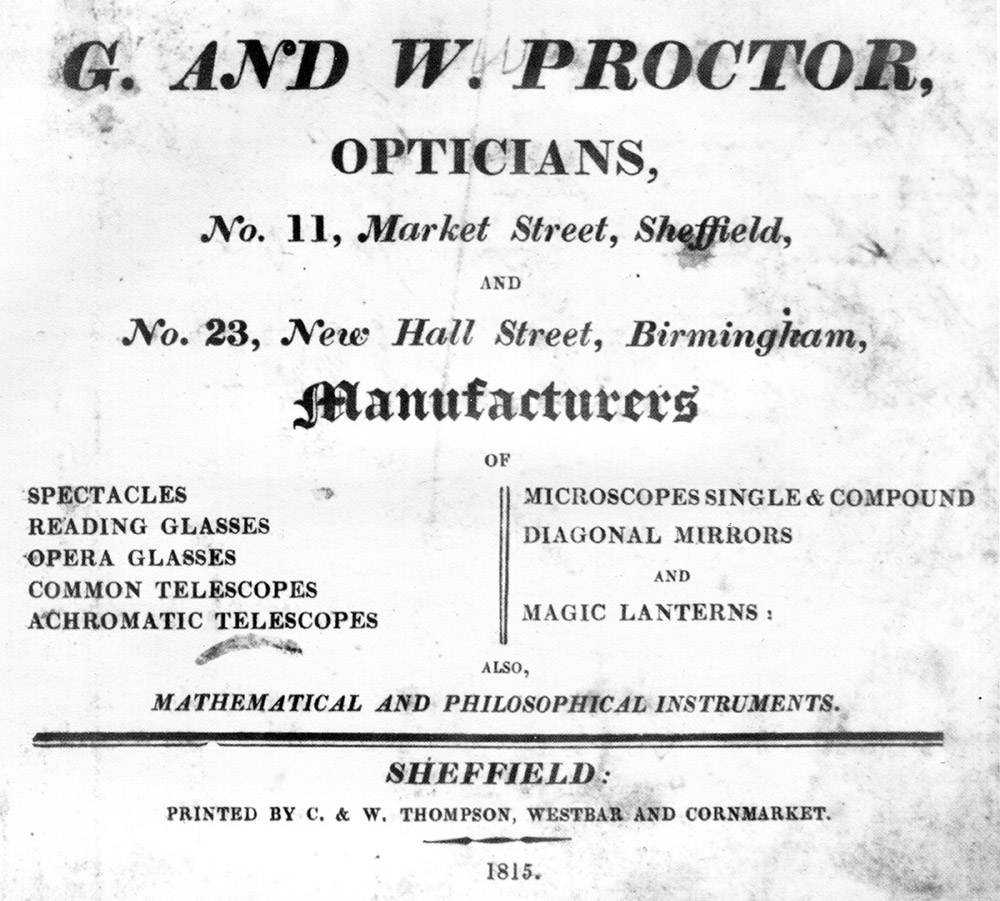

G. and W. Proctor, 1812 - 1818

by Brian Stevenson

last updated December, 2023

This series of businesses in Sheffield, England, began as producers of silver and brass ware, such as knives, forks, and other cutlery, fleams, powder flasks, and inkpots. By the early 1780s, Thomas Beilby joined the business of Charles and Luke Proctor, and began making eyeglasses, microscopes, and other optical apparatus. They were one of the first businesses to use a steam-powered glass-grinding machine, built in 1786. Branches were later opened in Birmingham and London, probably as distribution centers.

The Proctor and Beilby businesses are especially noteworthy for two reasons:

First, G. & W. Proctor published an illustrated catalogue in 1815, a copy of which is known to exist. The catalogue makes it clear that the Proctors manufactured microscopes, telescopes, and other optical apparatus for the wholesale trade. Only a very few instruments are known that are marked with Proctor’s/Beilby’s names (Figures 1-2, and 11-12), but many others are known that are identical to pictures in the catalogue, yet are unsigned or bear the names of other retailers (Figure 3-6). It is very likely that many or all of those were produced in Sheffield by Proctor & Beilby / G. & W. Proctor. This information suggests that there were businesses in other burgeoning industrial cities of England that also manufactured microscopes, telescopes, etc. for retailers in London and elsewhere. For examples, Philip Carpenter (1776-1833) produced optical goods for the wholesale market from ca. 1800 through 1837 in Birmingham and 1826 onward in London, and John Priston Cutts (1787-1858), a former apprentice of Priston & Beilby, formed a competing business in Sheffield ca. 1804.

Second, a man named John Holland (1794-1872) worked for Proctor & Beilby and G. & W. Proctor during the first two decades of the nineteenth century. Holland later became a journalist, and published a memoir of his life. He thus provided a rare, detailed look at scientific instrument-making during the early 1800s.

Proctor’s 1815 catalogue included five illustrations of compound and simple microscopes that they commonly manufactured. The catalogue was intended for wholesale trade, provided to retailers who would then sell these instruments to consumers. The Proctor businesses evidently sold a small number of microscopes under their own names, with three such signed instruments being currently known.

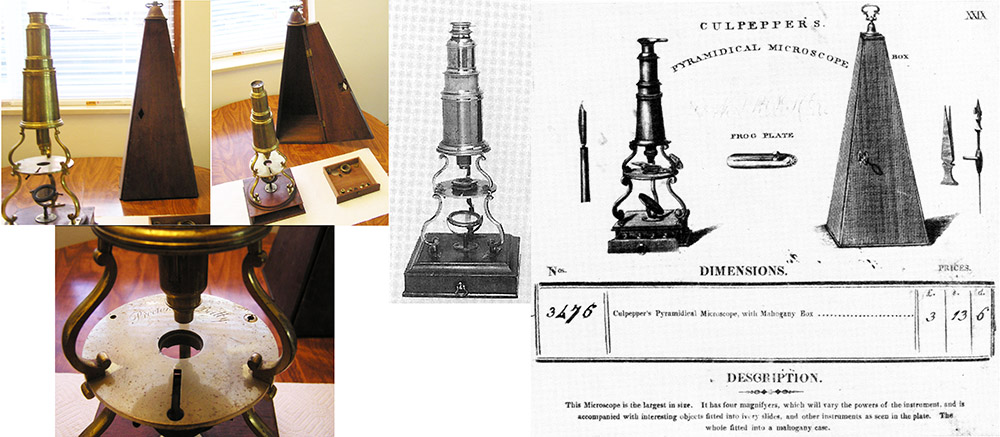

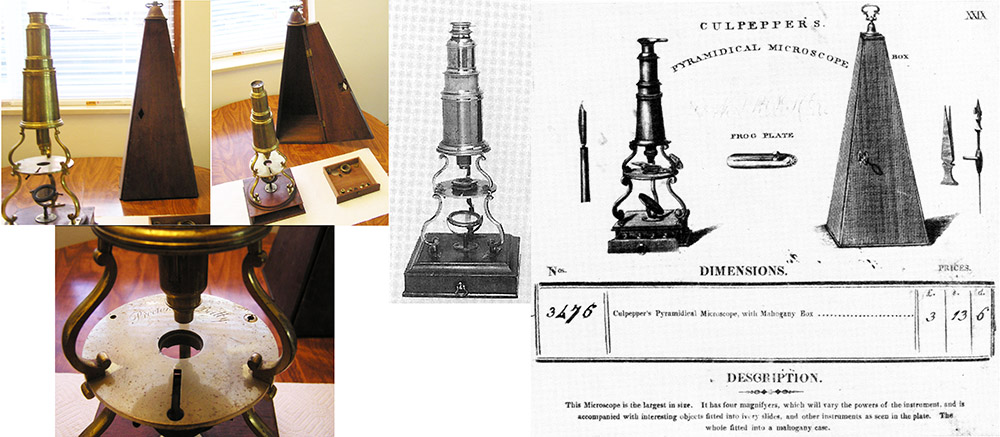

Figure 1.

Two “Culpepper’s Pyramidical Microscopes”, engraved “Proctors and Beilby” (left, in color, dateable to the early 1780s) and “G. & W. Proctor” (middle, black/white image, dateable to 1812-1818), and illustrations from G. & W. Proctor’s 1815 catalogue. They described it, “This microscope is largest in size. It has four magnifyers, which will vary in powers of the instrument, and is accompanied with interesting objects fitted into ivory slides, and other instruments as seen in the plate. The whole fitted into a mahogany case”. The wholesale price was 3£ 13s 6d. The comment that objectives “will vary in powers” was probably due to an absence of scientific method in their production, such that actual degree of magnification could not be precisely planned.

Figure 2.

A “Martin’s Microscope”, signed “G. & W. Proctor, London”, and the relevant illustrations from their 1815 catalogue. Proctor manufactured instruments in their Sheffield factory, and had a distribution arrangement in London. With a mahogany box and instruments, the wholesale price was 1£ 11s 6d. It was described, “This microscope is made to stand upon a table, taking care to let light fall upon the mirror. It has three different magnifyers, as exhibited in the plate, and is well worth the attention of all persons who are inquiring into the beauties of nature. It may conveniently be carried in the pocket.”

Figure 3.

Three microscopes that are identical / very similar to Proctor’s “Martin’s Microscope”. (A) In the Science Museum, London, and includes a wooden cabinet and accessories as described in Proctor’s 1815 catalogue. (B) In the Whipple Museum. (C) Also in the Whipple museum, this example is engraved “J. Saldarini, Peterborough”. Joseph Saldarini (ca. 1803 – 1888) was undoubtedly the retailer, not the maker, of this instrument - numerous wooden barometers are known with his name, but no other microscopes. Additional images of these microscopes, and another of the same design, are illustrated in https://www.microscopehistory.com/martin-pocket. Images adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes.

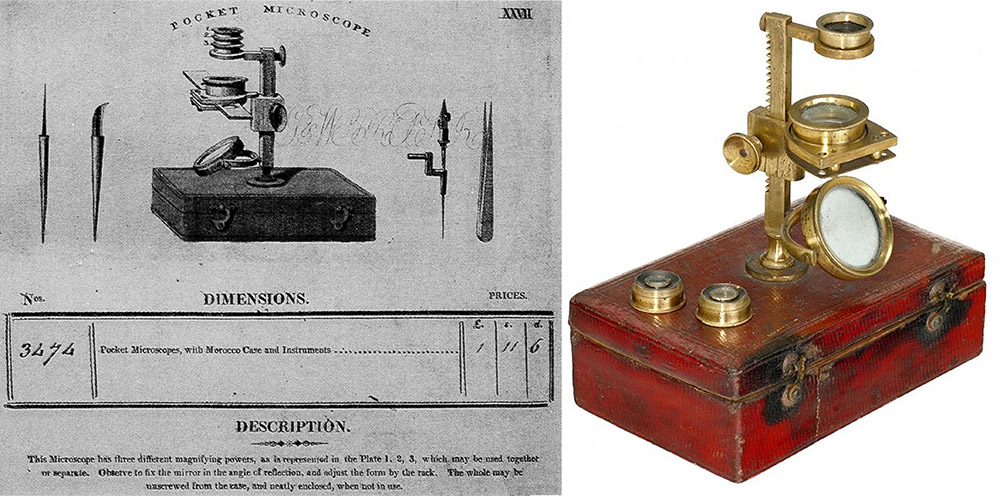

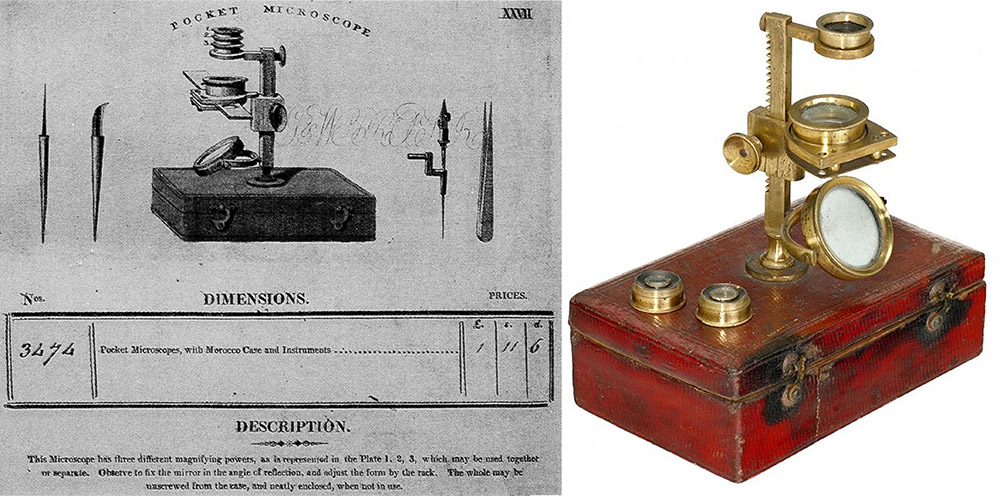

Figure 4.

Illustration and description of the “Pocket Microscope” from G. & W. Proctor’s 1815 catalogue, and an unsigned microscope that matches the description: “Pocket microscope with Morocco case and instruments. This microscope has three different magnifying powers, as is represented in the Plate 1, 2, 3, which may be used together or separate. Observe to fix the mirror in the angle of reflection, and adjust the form by the rack. The whole may be unscrewed from the case, and neatly enclosed, when not in use.” The design is essentially copied from the microscopes developed ca. 1800 by Robert Bancks (1765-1841), of London. Image adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

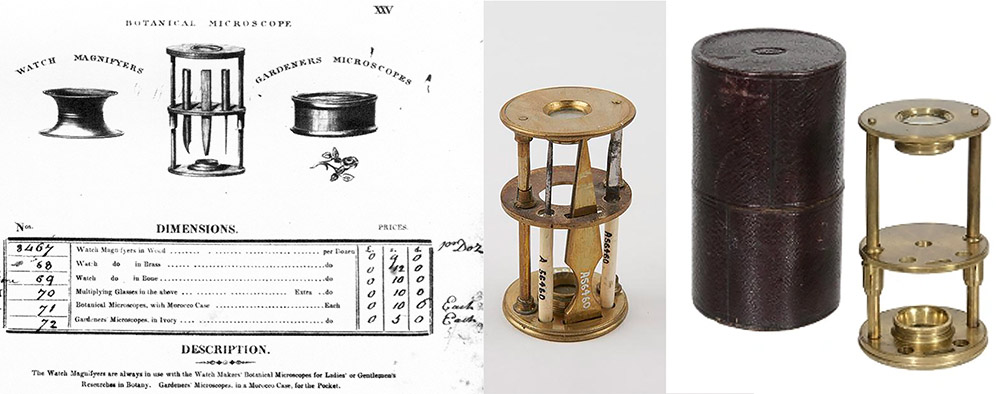

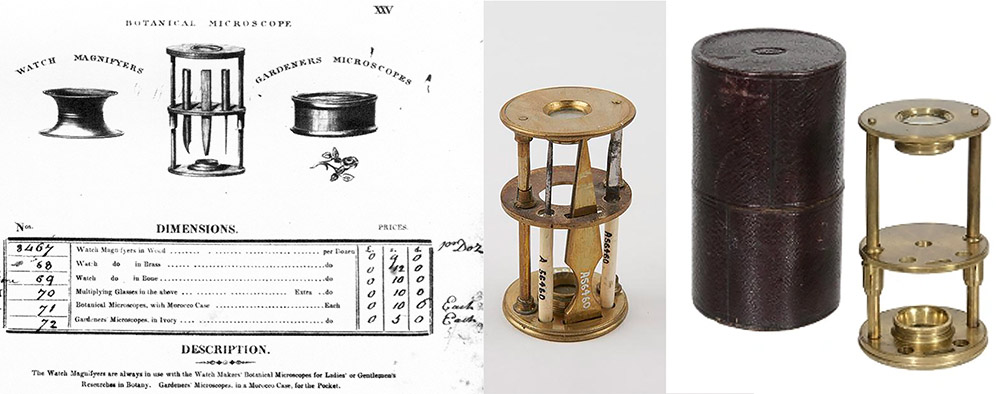

Figure 5.

Illustrations and descriptions of small magnifiers, including the “Botanical Microscope” from the 1815 catalogue. It is based on a design by William Withering (1741-1799), and often called by his name. Two unsigned microscopes that matches the Proctors’ illustration are shown to the right. The “Botanical microscope with Morocco case” was advertised “for Ladies’ or Gentlemen’s researches in botany”. Images adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co118821/withering-botanic-microscope-early-type-withering-botanic-microscopes or from an internet auction site.

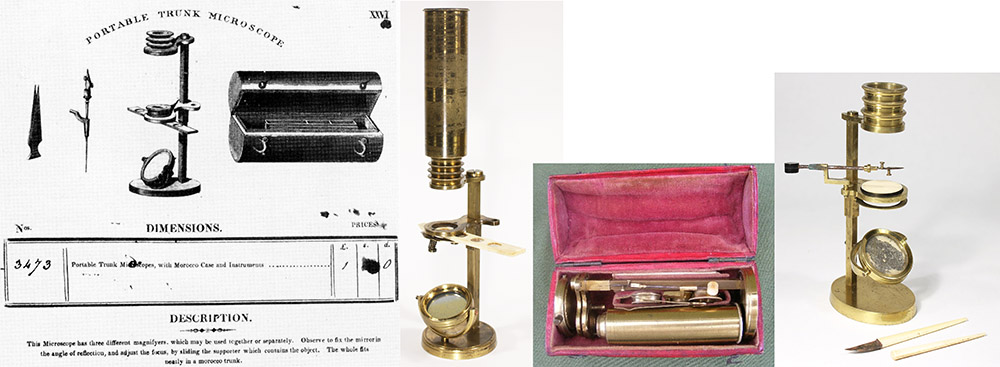

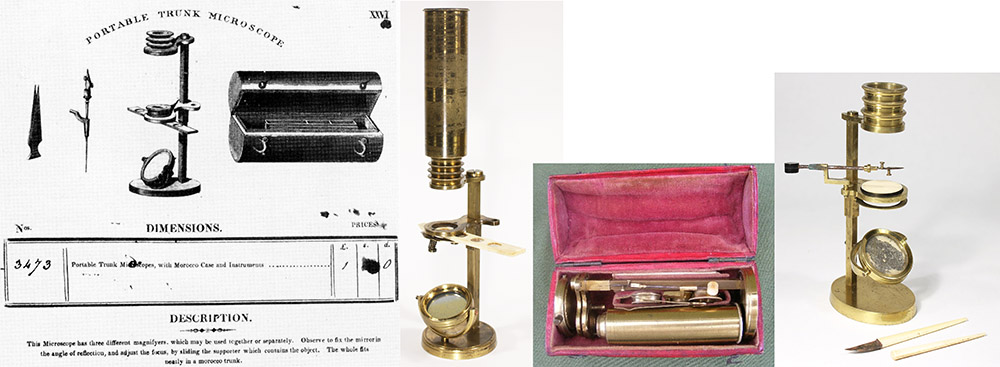

Figure 6.

The “Portable Trunk Microscope”, with “three different magnifyers, which may be used together or separately. Observe to fix the mirror in the angle of reflection, and adjust the focus, by sliding the supporter which contains the object. The whole fits neatly in a Morocco trunk”. Two similar, unsigned microscopes are also shown, one of which has a compound body, and fits into a cylindrical, Morocco-covered case that is seemingly identical to that of the Proctors. Images adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from internet auction sites.

Figure 7.

Cover of G. & W. Proctor’s 1815 catalogue. This and other images from the catalogue are adapted for educational, nonprofit use from Crom, 1989.

Figure 8.

The 1815 catalogue included illustrations and descriptions of other optical devices such as a camera obscura (an unsigned instrument that matches the illustration is shown here), a “Diagonal Mirror” for optical illusions, a magic lantern, and six pages of folding magnifying glasses. Image adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from the Getty Collection.

Figure 9.

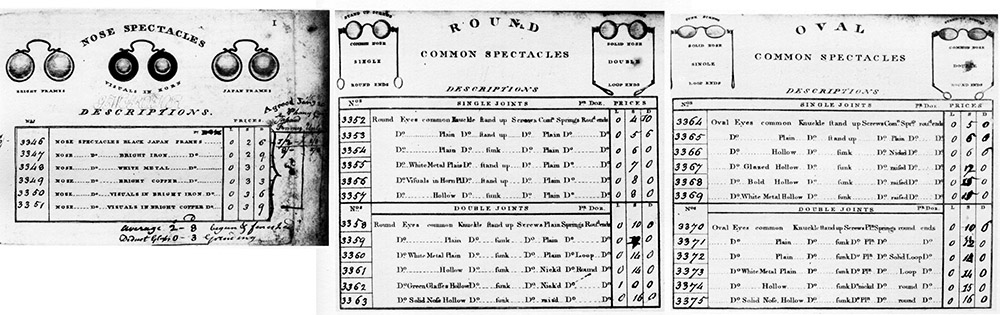

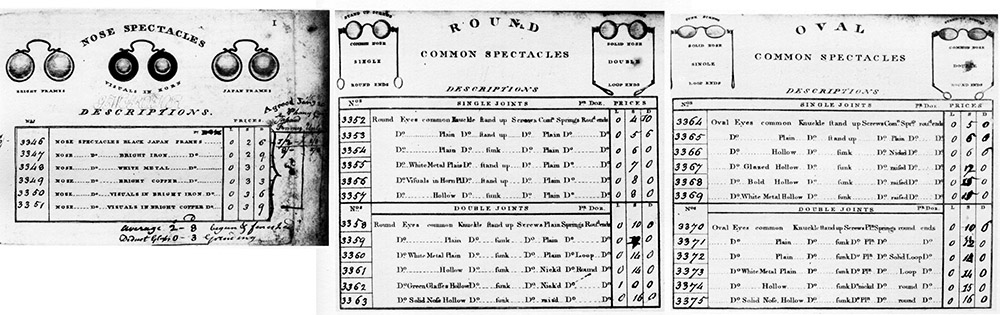

The 1815 catalogue included five pages of pre-made eyeglasses, in a variety of styles.

Figure 10.

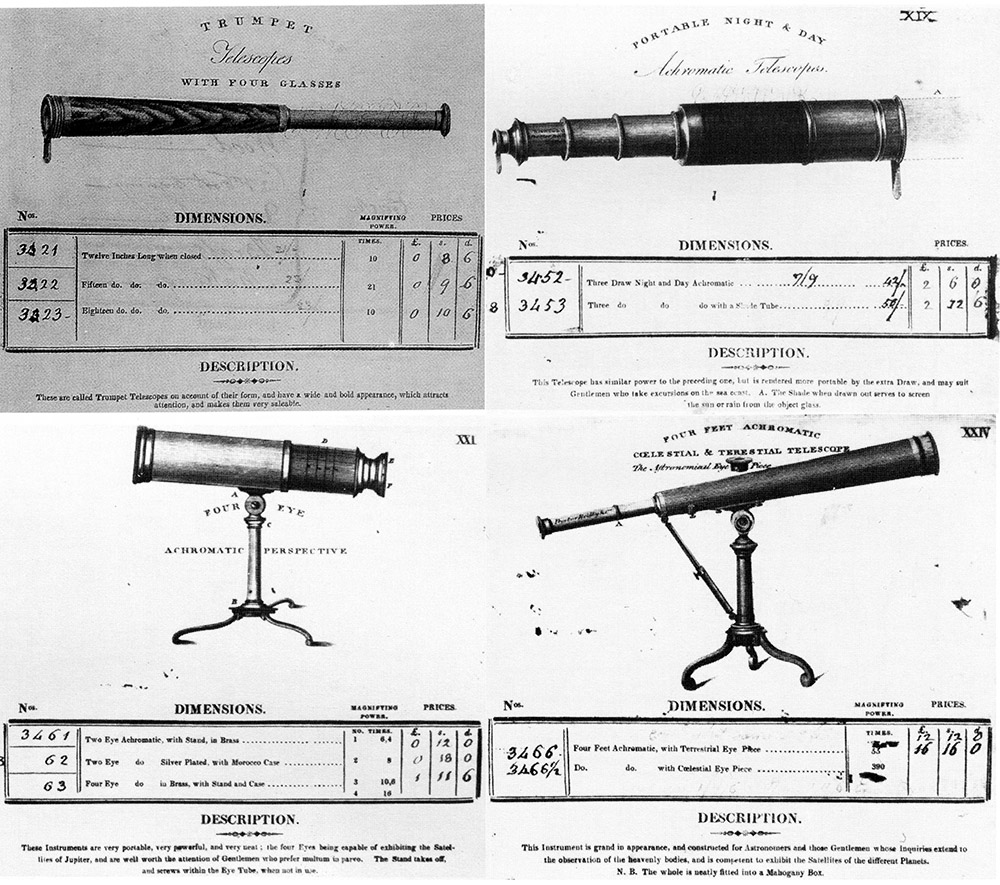

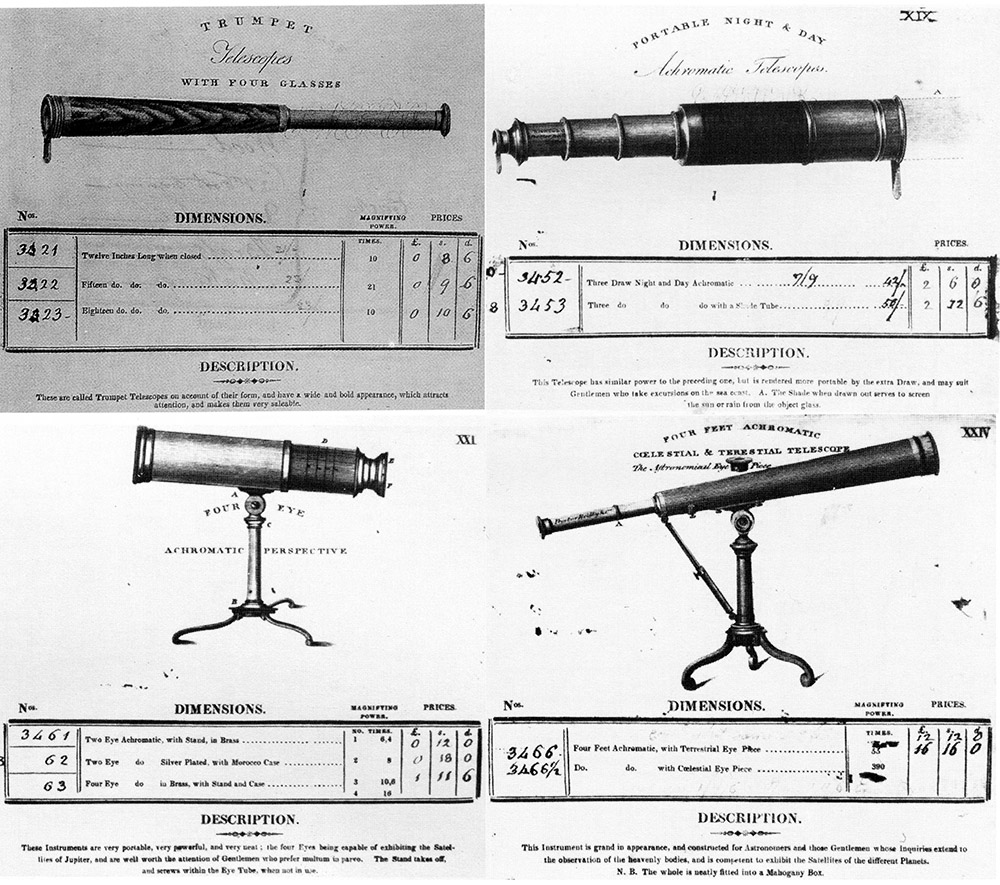

Telescopes were a major product of G. & W. Proctor, with the catalogue having 19 pages of different models.

Figure 11.

A four-draw telescope that was manufactured by Proctor, Beilby & Company (dates 1808-1812), and distributed by them in London. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Figure 12.

A ring dial (solar time piece) by Proctor, Beilby, and Company, London, ca. 1808-1812. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Figure 13.

Although it was not listed in the 1815 catalogue, this folding, hand-held simple microscope can be attributed to the Proctor(s) and Beilby iteration of the business, ca. 1780-1800. This, and several other known examples, were distributed with cases marked “W. Rushby, Cherry Tree Hill”. William Rushby (ca. 1745 – ca. 1810) was a maker of “Sheaths, Paper Inkpots, &c.”, and Cherry Tree Hill was a village outside Sheffield. Rushby was not a glass or metalworker, so it is reasonable to conclude that he supplied cases to the microscopes’ maker. Proctors & Beilby / Proctor Beilby were the only such manufacturers near to Rushby. A detailed analysis of these simple microscopes is available elsewhere on this site.

Brothers Charles and Luke Proctor (born in 1743 and 1747, respectively) were sons of Jonathan Proctor. Father Jonathan made fleams (bloodletting devices), knives, and other cutlery. After completing apprenticeships as Cutlers, the sons set up their own cutlery businesses, working both together and individually. A fleam marked “Cha. Proctor” is shown in Figure 14.

Charles Proctor married a woman named Dorothy ca. 1773, and had four children: George (born 1774), Deborah (born 1775), William (born 1776), and Luke (born 1779). Sons George and William later inherited their father’s business. Deborah married Thomas Beilby, Jr., son of Charles & Luke’s business partner, and also an eventual owner of the Proctor/Beilby business. Son Luke died while young.

Around 1780, the Proctor brothers formed a partnership with Thomas Beilby, Sr., as “Proctors & Beilby” (Figure 15). John Holland recalled that, “Beilby was a Birmingham man, and I think practiced in Sheffield as a teacher of drawing. How the partners came together, I do not know, but they commenced making various articles in brass”.

Beilby does not appear to have brought any particular skill to the partnership, and so may have been a source of money to expand the operation. Holland wrote, “Proctor and Beilby erected that capital and extensive range of buildings forming the greater part of the west side of Market-street, the front portion comprising workrooms and dwelling-house; the commodious workshops ranging immediately behind”.

Thomas Beilby married Isabella Fell on January 1, 1780, in Sheffield. Their first child, Thomas, Jr., was born in 1781.

Holland reported, “Luke Proctor was an agreeable man of fashion, an accomplished violinist, and he soon fiddled himself out of the firm. Charles, a lover of music too, was a quiet, assiduous, and successful man of business, and I remember how I used to look for his white wig opposite one of the windows in the old Cutlers' Hall, at ‘The Feast’, where he sat ‘above the salt’. He was a widower when first I knew him, his wife Dorothy being named on a tablet in St. Paul’s Church. His family consisted of himself, his three sons - Luke, George, and William - his daughter, Deborah, and last, but not least, in those days, his sister, Miss Nancy - a sharp little consequential woman, who did a great part of the familiar book-keeping of the concern, including especially the entering of the men's work and wages”.

Luke Proctor left the partnership during the mid 1780s. He operated several other businesses, alone or in partnership, producing cutlery and silverware. The brass and optical works was known as “Proctor and Beilby” after Luke’s departure (Figure 16).

Proctor and Beilby built a steam engine in 1786 to help with grinding lenses. It was one of the first applications of steam power for that application in Britain.

Holland’s memoir spans the development of instrument making from separate cottage industries to incorporation into a manufacturing center. He wrote that his father, also named John, “was a maker of optical instruments. He worked at his trade at home in a large garret, which was furnished with turning lathes and other machinery pertaining to his craft”. The elder Holland’s telescopes and other instruments were sold to Proctor & Beilby, who then moved them along the wholesale trade. The son worked at home with his father from a young age, until both moved to Proctor & Beilby’s new manufacturing facilities.

By the time the younger John Holland entered employment with Proctor & Beilby, in 1807 when he was thirteen years old, their premises housed numerous workmen and produced a wide variety of apparatus. Holland wrote, “There was a systematic distribution of work throughout the establishment, one man being mostly employed on a special class of articles, in the making of which he acquired great dexterity. Each, too had his own ‘side’, or work-board, and ‘engine’, as his lathe was called, about which were arranged ‘chucks’ of all shapes.”

“I may remark that the variety of articles manufactured was very great, comprising telescopes of all sorts, from the four feet achromatic on brass stand, to the simple spyglass of a few inches in length; and microscopes – from the “Culpepper’s pyramidal” – grand affair in those days! - to the pillared magnifier an inch high … and then there were spectacles of all sorts … But besides articles which might be called optical in a sense more or less strict, the workshop turned out an immense quantity of other things: two may be mentioned, viz., tinder-boxes and ink-pots”.

“I need hardly say that the ‘glazing’ or fitting the higher class of instruments with glasses was in no degree scientifically conducted: of the doctrine of optics, in the abstract, the men and women engaged, of course, knew nothing. They knew that a telescope was called achromatic, which had a compound object glass; and they could measure, in a rude way, the focal length of the lenses used, so that adhering to a special formula, they succeeded in practically producing a good telescope.”

Holland provided intimate details of the workmen and their particular products:

“William Padley was the brass caster, and Thomas Stovin the glass caster, as they were called; the latter melted pieces of broken glass … on a red-hot iron plate; then, with a spatula, transferred the plastic mass from a mould under a screw press, out of which it came ready for grinding as a ‘spectacle eye’.”

“But the moulding and casting in ‘front sand’ (i.e. sand-casting brass into shapes) was to me the more interesting operation, and at this Padley was an adept. And boy as I was, I was both surprised and sorry to see him put into the melting pot shovelsful of the fine, plump pennies of George the Third’s reign, which I thought might have been so much better used. But I lived to learn that each of these coins weighed nearly an ounce – while copper in the ingot was nearly two shillings a pound!” Thus we learn that many of the microscopes and other brass instruments of the early 1800s may have once been coins.

“Besides the brass and other work which employed so many hands in the Sheffield shop, there were two branches of the manufacture carried on in a ‘mill’, or ‘wheel’ … on the Rivelin, a picturesque river… I allude to the boring and turning of sycamore and mahogany outsides of telescopes … and the still more important and curious operation of glass grinding, comprising the production of lenses of every size and curve, from the hemispherical ‘bulls eye’ of the magic lantern to the convex or concave ‘spectacle eye’ ground in or upon ‘tools’ of large radius.”

Of particular interest to modern microscopists: ca. 1807, “Microscopes of all sorts, as well as various optical and other knic-knacs, were mostly made by Dickey Hobson, a Birmingham man”. Holland also wrote that during the mid-1810s, when the business was in decline and many workmen had left for other opportunities, “I alone was left on the premises to make, as far as the brass work was concerned, whatever might be wanted in the entire range of the pattern book”. Holland’s words indicate that it is highly likely that microscopes of the patterns of Proctor & Beilby / G. W. Proctor were handmade by either Richard Hobson or John Holland.

Of other workmen:

“Prime, as a workman, was George Hadfield, and not less remarkable as a toper than a turner. I used to wonder at the desperate dash with which, after his weekly drunken fit, his trembling hand applied the tool to a brass-casting, used in the successful production of large ‘day and night’ telescopes. John Holland (the author’s father) was also employed in similar work, and his brother Amos, in making accurate imitations of the 14, 18, and 27 inch telescopes of the celebrated Dollond.”

“William Egginton made long ‘six-glass’, or, as they were called from their form, ‘trumpet telescopes.” (see Figure 10).

“Another … was Johnny Coe, a little, knock-kneed man … made ‘reading glasses’, as they were called, i.e., a sort of polished horn box containing a magnifying glass from one to three inches in diameter, tortoise-shell spectacles (and) lorgnettes … Coe was an elderly man when I first knew him, and had been with the Proctors from the first, was early employed by them in making ‘ring dials’.” (see Figure 12).

“Tinderboxes and ink-pots … these articles being made of brass, were all polished by old Daniel Vaughan, a Chelsea pensioner, who, after formerly doing duty as a recruiting sergeant in Sheffield, went abroad and fought beside General Wolfe at Quebec … Ben Wright, another pensioner, had ‘seen service’ – at the alehouse, possibly in the streets – but he had, without leaving the town, won the common trophy – a wooden leg; and I used to look with boyish wonder at the way he ‘treddled’ at his lathe.”

Holland also reported that the workmen at Proctor and Beilby, and other such businesses, required employees to purchase many of their necessities through the employers. These included “various articles of food, especially cheese and tea, and every description of clothing, from the workman’s outermost garment to his wife’s undermost garment”. The prices of these goods were heavily marked up by the employer, and payment was taken out of paychecks. This not only created additional profits for the employer, but “tethered the workman by a perpetual debt, which it must be admitted, he did not always discharge.”

“Charles Proctor, the respected head of this large establishment, died July 4th, 1808, and was carried y six faithful workmen to his grave in Saint Paul’s Church. He was described in the local newspaper as ‘a most useful member of the community at large, taking on all occasions a most active, persevering part to accomplish any object for the benefit of society’. He left behind, according to this ‘Gossip’s Gazette’, property to the amount of thirty thousand pounds.”

After Charles’ death, the business reorganized as “Proctor, Beilby & Company”, owned by Charles’ sons, George and William, Thomas Beilby, Sr., and his son, Thomas, Jr. As noted above, Thomas Beilby Jr. had married George and William Proctor’s sister, Deborah. Thomas Jr. and Deborah lived in Birmingham, where he owned a publishing company.

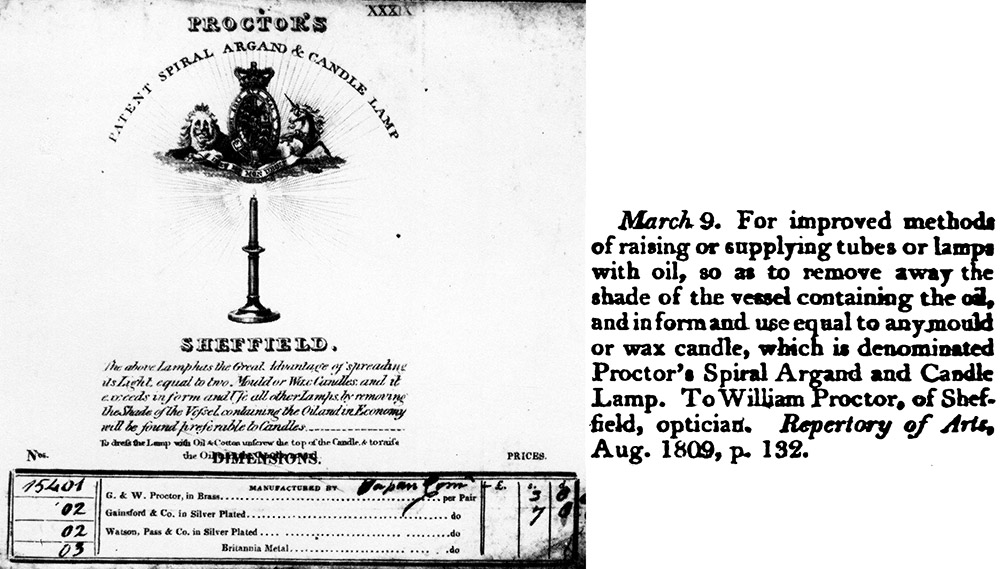

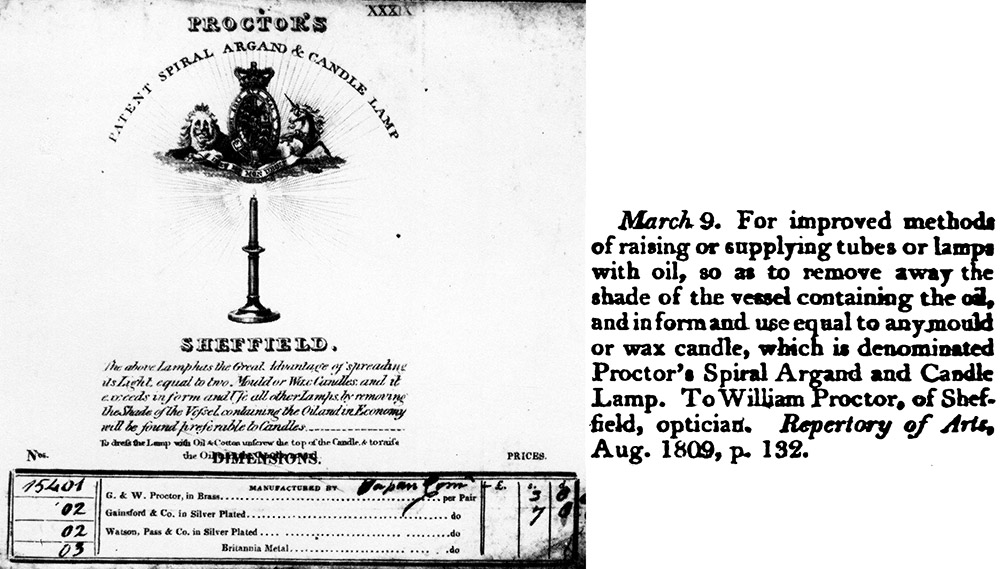

William Proctor was awarded a patent in 1809, for an oil lamp. Proctor’s “Patent Spiral Argand and Candle Lamp” was still featured in their 1815 catalogue (Figure 17). Holland wrote in 1867, “In the latter years of existence of the Market-street firm, the manufacture of an article was commenced, which, while in no way related to optics, promised for a time to realise the sanguine expectations of the inventor. I allude to ‘Proctor’s patent argand candle-lamp’, so called from its resemblance to a brass candlestick, the oil being contained in a candle-shaped tube. The contrivance was certainly ingenious, but three causes concurred to make an end of the speculation – the lamp could not e sold cheap, it required frequent manipulation, and it had a common cotton wick that required attention. Although several tons weight of this lamp were made and sold, it would probably be impossible to obtain a specimen at any price.”

The Proctors and Beilbys were also involved with a separate partnership, “Blackwell, Proctor, Dakin & Company”, which manufactured “stove grates, fenders, and fire irons” in Sheffield. William Proctor was awarded a patent in 1808 for “improved methods of melting and using malleable wrought iron or steel”. That partnership was dissolved in 1811, and the business was continued by William Proctor alone.

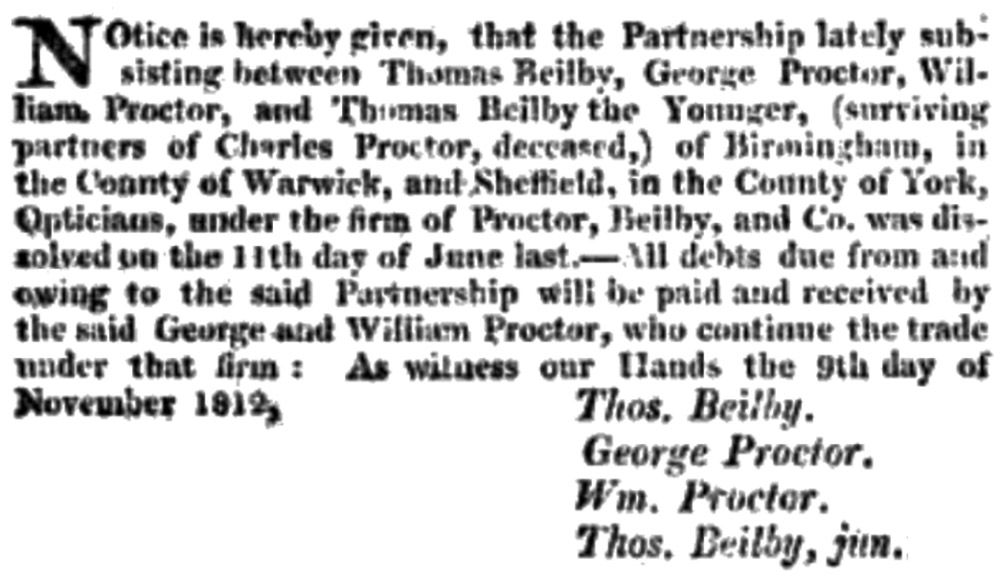

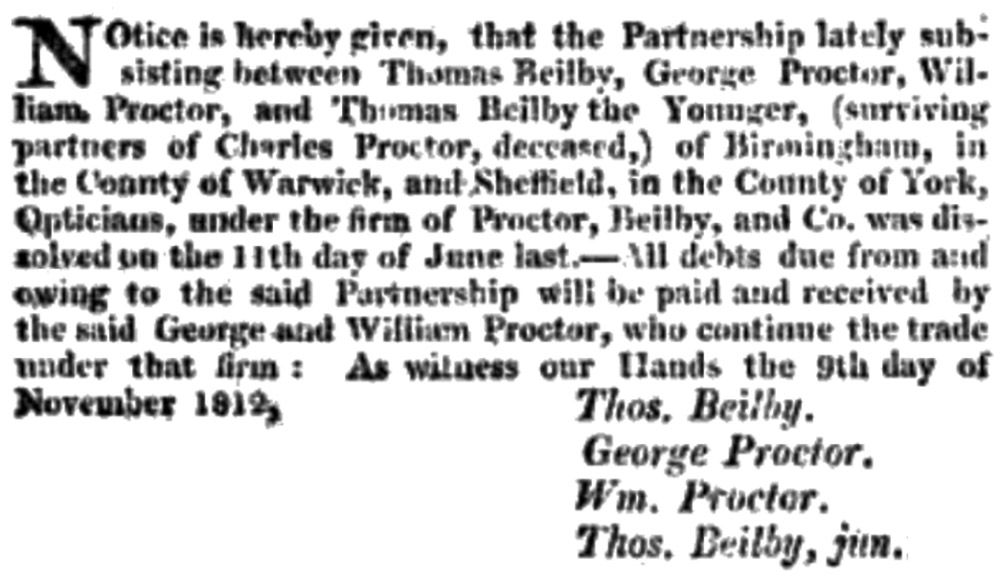

The Proctor, Beilby & Co. optical/brass partnership was dissolved in 1812. It was continued by the Proctor brothers as “G. & W. Proctor.” George Proctor soon moved to Birmingham, and opened a branch shop in that city. Thomas Beilby, Sr., also moved to Birmingham, and operated a saw factory.

Holland wrote that after the death of Charles Proctor, the business had “reached its culminating period of prosperity; thenceforth its fortunes were downward. Not only were competitive firms being established, but changes in the modes of manufacture at current prices, and carrying on traffic generally, were taking place. Moreover, Mr. William Proctor was less a man of business than a man of genius, if a fondness for making all sorts of experiments can justify the appellation. As the business declined, or temptations were offered from other quarters, the workmen, including those I have named and many others, successively went or were sent away, until I alone was left on the premises to make, as far as the brass work was concerned, whatever might be wanted in the entire range of the pattern book.” Competitors would have included former apprentice John Priston Cutts, who established an optical instrument-making business in Sheffield ca. 1804.

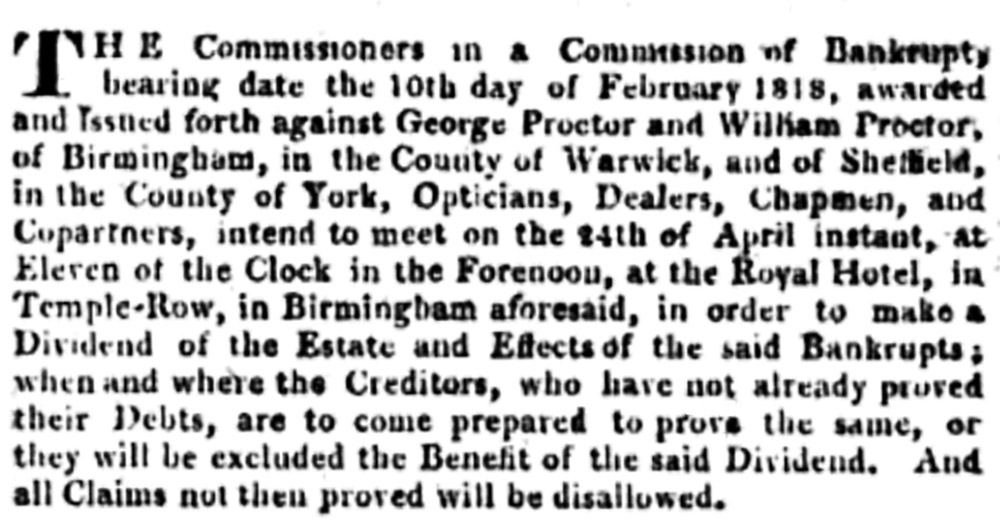

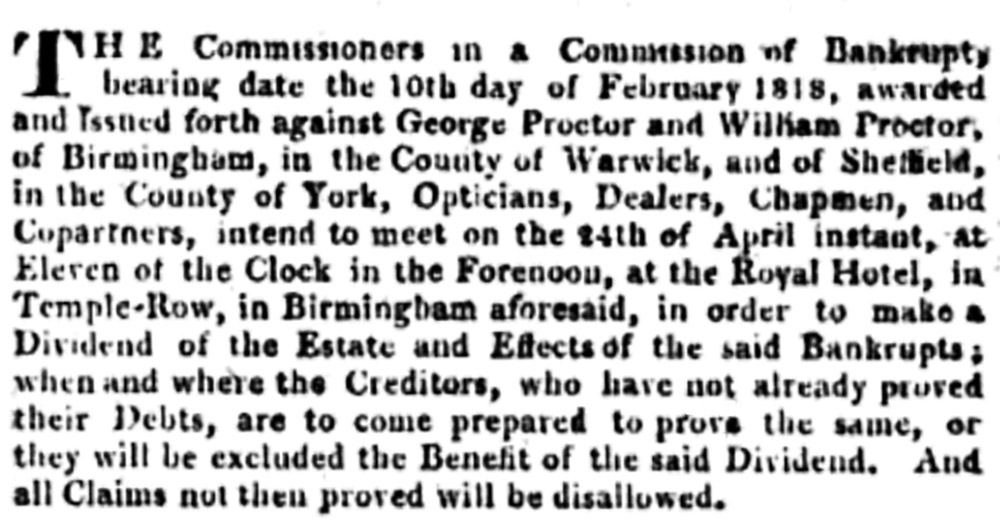

George and William Proctor filed for bankruptcy in 1818 (Figure 19). Filings referred to both men as “opticians”, indicating that William’s cast iron business was not involved. A Sheffield newspaper announced the auction of “sixteen valuable turning engines, a boring engine, a powerful fly, two brushing engines, two glazing engines, a hearth of tools, two grindstones in frames, draw bench with all the valuable tools, large shears, pair of rollers, two glass cutting machines, a globe grinder, a water engine twenty-five capital vices, a quantity of glazers, mandrils, gauges, files, and other tools, beam and scales, metal weights, work benches, five cwt. of brass tools, and five cwt. of metal tools, writing desks, two iron bookcases, shelving, counters, cupboards, tables, nests of drawers, work benches, stools &c. At the Wheels, near Sheffield, all the machinery for glass grinding, lot of telescope wood, lot of timber, quantity of old iron and old metal, a turning engine, a joiner’s bench, vice, and quantity of tools.”

By 1822, William was again operating an optical business is Sheffield (Figure 20). It is not known whether that firm manufactured microscopes and other such items. William also operated his cast iron works at the same location. He disappeared from business directories after 1828.

Figure 14.

A two-bladed fleam that was manufactured by Charles Proctor. Possibly dates to the early 1760s, after he completed his apprenticeship but before Luke completed his. Image adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Figure 15.

Excerpt from a 1787 directory of Sheffield. At that time, Charles and Luke Proctor operated their optical goods business in partnership with Thomas Beilby, Sr., as “Proctors and Beilby”, and a separate business entity as manufacturers of cutlery and small brass items. Luke also had a separate business at another location, producing silver items. Their father, Jonathan Proctor, had a separate business that produced fleams.

Figure 16.

Excerpt from a 1790 Sheffield directory, after Luke Proctor had left the business, which was now called “Proctor and Beilby".

Figure 17.

William Proctor patented an oil lamp in 1809. The 1815 catalogue indicates that it was also manufactured / distributed by Gainsford & Co. of London, and Watson, Pass & Co. of Sheffield and London.

Figure 18.

“Proctor, Beilby & Co.” was dissolved in 1812, and continued by the Proctor brothers as “G. & W. Proctor”. From “The London Gazette”.

Figure 19.

G. & W. Proctor was dissolved in bankruptcy during 1818. From “The London Gazette”.

Figure 20.

This excerpt from the 1822 “History, Directory & Gazeteer of the County of York” indicates William Proctor maintained his cast iron business, and re-established an optical business after the dissolution of G. & W. Proctor. The nature of his optical business is not known.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Joe Zeligs for helpful discussions and for assistance in locating images, and to the University of Kentucky Interlibrary Loan Department.

Resources

Clifton, Goria (1995) Directory of British scientific instrument makers 1550-1851, Zwemmer, London, pages 224-225

Crom, Theodore R (1989) Trade Catalogues 1542-1842, Crom, Melrose Florida, pages 357-370

A Directory of Sheffield (1787) Gales & Martin, Facsimile reprinted in 1889 by Pawson & Brailsford, Sheffield, pages 72-73

The Edinburgh Annual Register (1809) Notice of William Proctor’s patent for an oil lamp, page 458

England census and other records, accessed through ancestry.com

The European Magazine, and London Review (1818) “An alphabetical list of bankrupts … Proctor, William, Sheffield, optician; Proctor, George, Birmingham, optician”, Vol. 73, page 367

The Examiner (1818) “Tuesday’s London Gazette … Bankrupts … G. and W. Proctor, Birmingham, opticians”, page 170

Habershon, Matthew H. (1893) Chapeltown Researches, Archaeological and Historical, Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co., London, page 176

History, Directory & Gazeteer of the County of York (1822) page 337

Hudson, William (1874) The Life of John Holland, of Sheffield Park, Longman, Green, and Co., London

Hutton, William (1809) An History of Birmingham, includes this statement: “Published by the same Author, and to be had of Thomas Beilby, jun. and Co. Birmingham”

Leader, Robert E., ed. (1876) Reminiscences of Old Sheffield: Its Streets and Its People, Second edition, Leader & Sons, Sheffield, pages 94-97

The London Gazette (1811) Notice of dissolution of Blackwell, Proctor, Dakin & Co., page 1414

The London Gazette (1812) Notice of dissolution of Proctor, Beilby & Co., page 2332

The London Gazette (1819) Notice of closing of accounts for G. and W. Proctor, page 601

The Monthly Magazine (1808) “At Sheffield, Mr. Charles Proctor, optician, 70”, page 80

Morrison-Low, Alison D. (1994) Proctor & Beilby, part 1: early 19th century scientific instrument making in the English Midlands, Bulletin of the Scientific Instrument Society, number 41, pages 9-15

Morrison-Low, Alison D. (1994) Proctor & Beilby, part 2: Proctor & Beilby’s Sheffield, Bulletin of the Scientific Instrument Society, number 42, pages 17-21

Morrison-Low, Alison D. (2007) Making Scientific Instruments in the Industrial Revolution, Ashgate, Hampshire

Philosophical Magazine (1808) “List of patents for new inventions … To William Proctor, of Sheffield, in the county of York, optician, for his improved methods of melting and using malleable wrought iron or steel, July 6”, page 239

Pigot and Co.'s National Commercial Directory (1828) page 1091

The Repertory of Arts, Manufactures, and Agriculture (1809) “Specification of the patent granted to William Proctor, of Sheffield, in the County of York, optician; for improved methods of raising or supplying tubes or lamps with oil, so as to remove away the shade of the vessel containing the oil, and in form and use equal to any mould or wax candle, which he denominates Proctor's Spiral, Argand, and Candle Lamp”, Vol. 15, pages 132-133

Sheffield Directory and Guide (1828) John Blackwell, Sheffield, page xvi

The Tradesman (1809) A patent lamp, pages 444-446

Wrightson's New Triennial Directory of Birmingham (1818) “Thompson, Griffin, Beilby, and Co., saw manufacturers, Great Brooke-street”, page 128

The Universal British Directory of Trade, Commerce, and Manufacture (1790) page 404

Will of Thomas Beilby, Sr. (1827) accessed through ancestry.com