Isaac Cooke Thompson, 1843 - 1903

Thompson and Capper

by Brian Stevenson

last updated July, 2024

Isaac C. Thompson was a significant member of the scientific communities of Liverpool, England, during the last quarter of the nineteenth century. He was a Fellow of the Royal Microscopical Society, Fellow of the Linnean Society, and a member of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, the Quekett Microscopical Club, the Liverpool Microscopical Society, the Liverpool Biological Society, and the Liverpool Physical Society. A colleague wrote that Thompson was "recognised as the leading local authority on the microscope".

During his later years, he developed expertise in the study of copepods (e.g. Figures 1 and 4). Connected to that interest, he played an important part of the establishment of the Liverpool Biological Society’s Port Erin Biological Station.

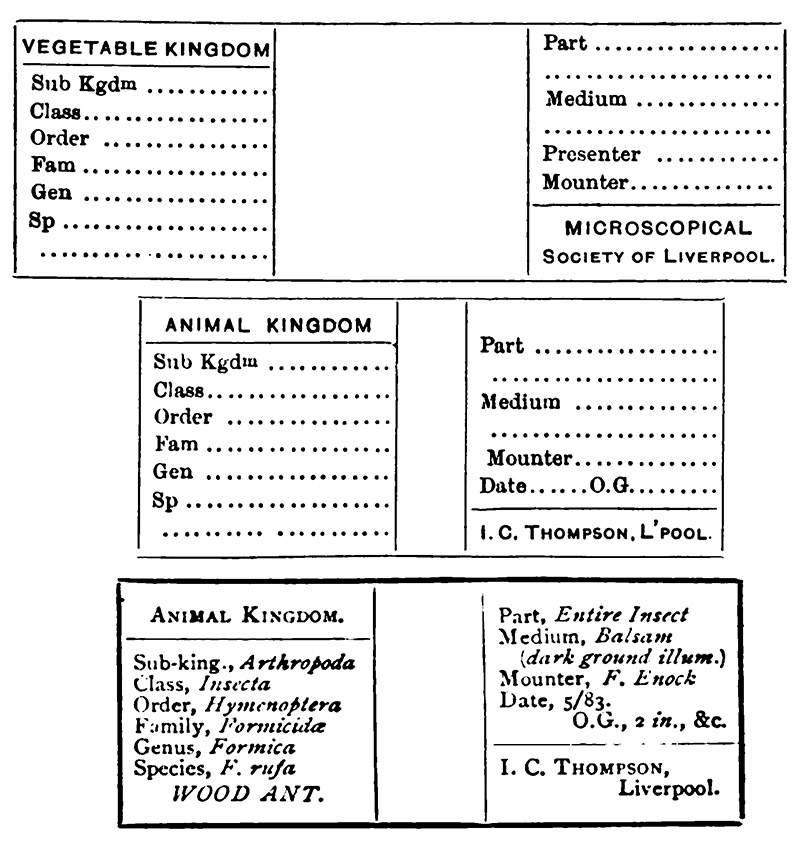

I.C. Thompson prepared good quality microscope slides (Figure 1). His earlier mounts are identifiable by shield-shaped labels that bear the initials “I.C.T.” and his family crest. He designed labels ca. 1883 that provide spaces for details on each specimen’s scientific name, source, date, etc., which also bear his name and address (Figures 1 and 2).

Thompson was a partner in the homeopathic pharmaceutical business of Thompson and Capper, assuming that position in 1869 upon the death of his father, George Thompson. Thompson and Capper sold microscopes, microscope slides, associated apparatus, and magazines (Figures 5-8). That firm is still in business, as a manufacturer of vitamins, minerals, and other dietary supplements.

Figure 1.

Microscope slides by Isaac C. Thompson. Left: dated 1877, identified by Thompson’s initials and family crest. Right: mounts of microscopic crustaceans by Thompson, dated 1886 and 1887. He designed this type of label in 1883 (see Figure 2). From the author's collection or adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

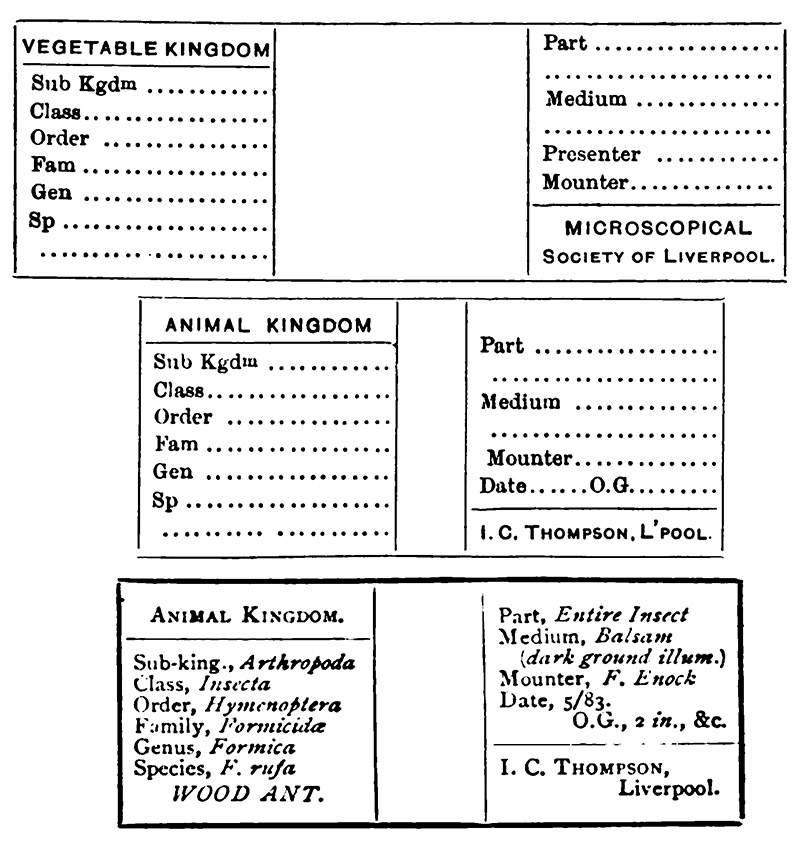

Figure 2.

Examples of slide labels that were designed by I.C. Thompson in 1883. From “Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip” and “Microscopical News and Northern Microscopist”.

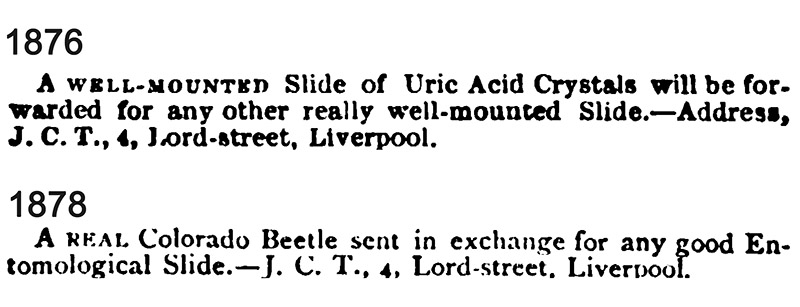

Figure 3.

Exchange advertisements from I.C. Thompson, 1876 and 1878, both from “Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip”. Publications often printed his first initial as “J.”.

Figure 4.

Photomicrographs of copeopods that were mounted by Isaac C. Thompson (see Figure 1). Left: Peltidium interruptum (10x objective). Right: Candace pachydactyla (now Candacia pachdactyla) (3.5x objective).

Figure 5.

Thompson’s business, Thompson & Capper, retailed microscopes and microscope slides, such as these mounts by John W.D. Hume (1851-1912). Images adapted from Paisley, 2012.

Figure 6.

Thompson & Capper was the original distributor of “The Botterill Trough”, designed ca. 1878 by Charles Botterill (1825-1894). The trough measures 3 inches wide x 1 inch high. Images adapted from an internet auction site, for nonprofit, educational purposes.

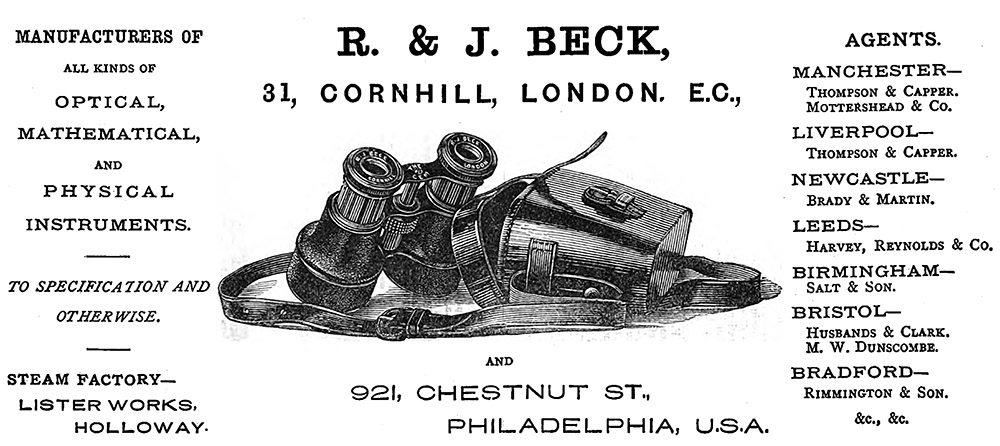

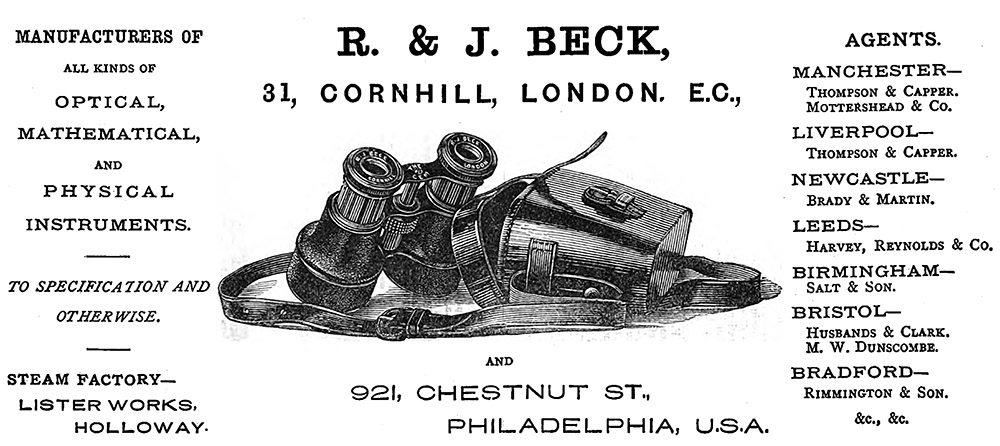

Figure 7.

An 1879 advertisement from R. & J. Beck, noting that Thompson and Capper were a distributor of their microscopes and other optical instruments. From “Nature”.

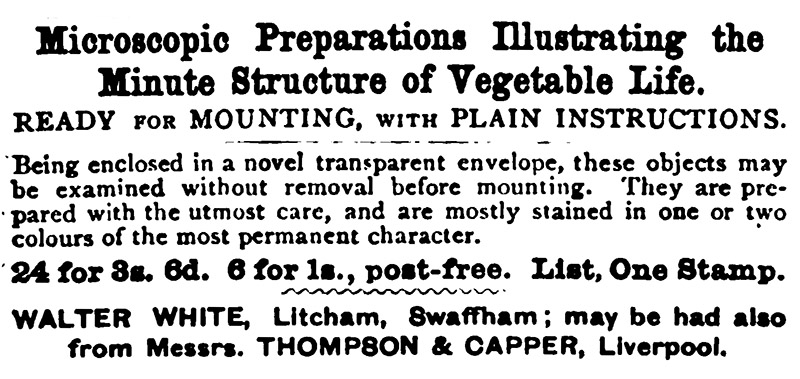

Figure 8.

Thompson and Capper also distributed of the unmounted botanical specimens that Walter White (1841-1923) produced for use by amateur slide-makers. From “Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip”, 1889.

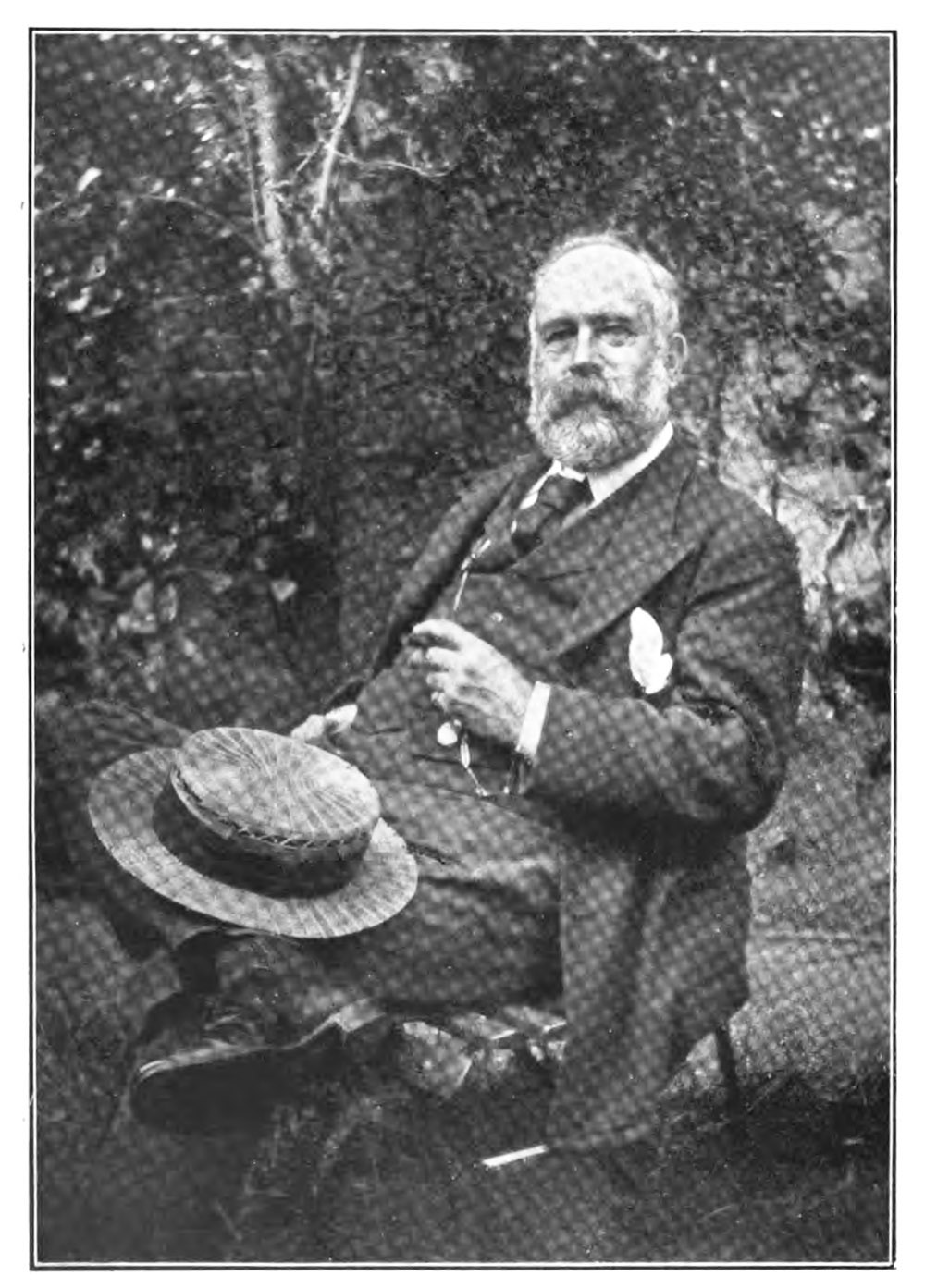

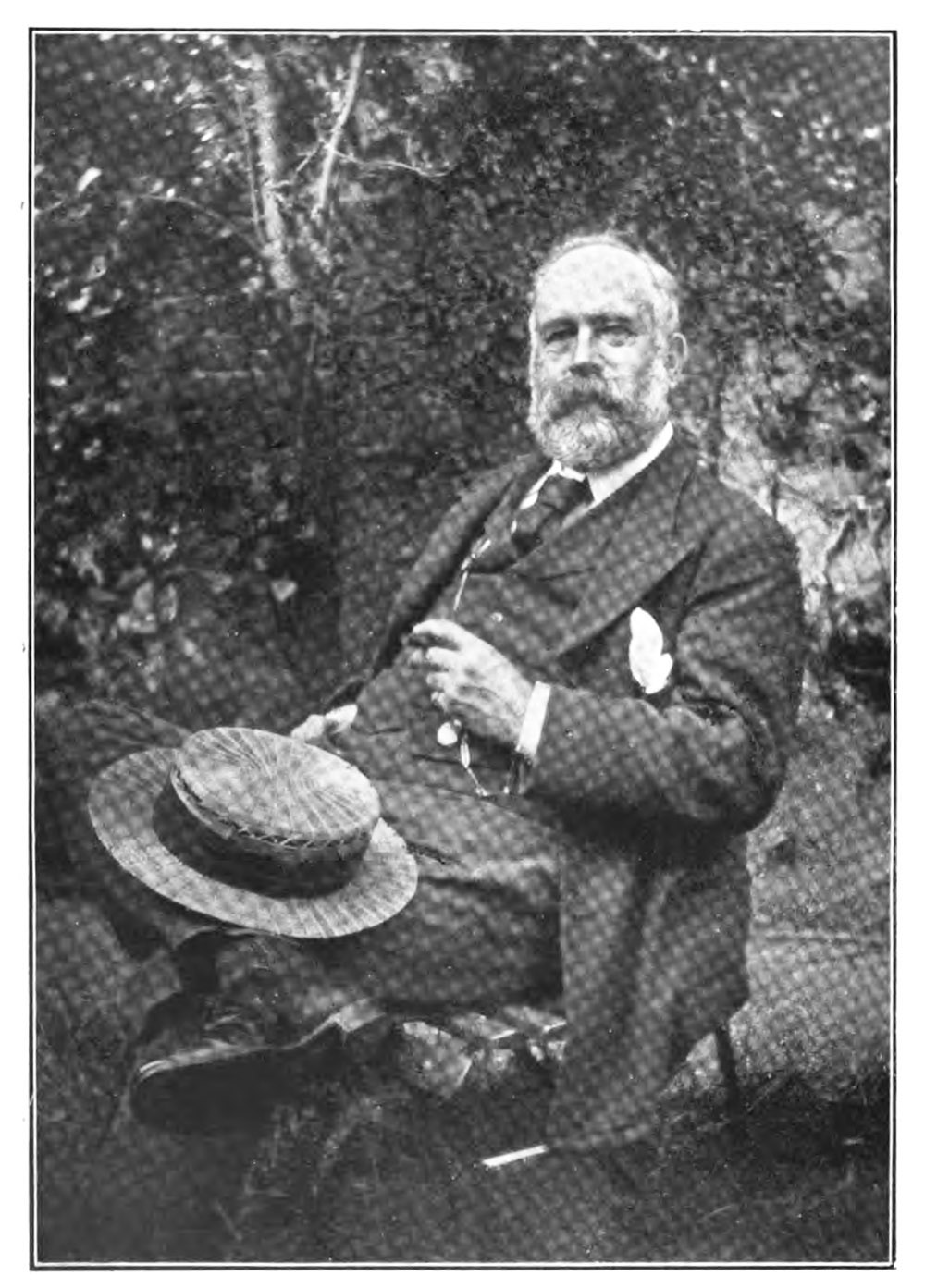

Figure 9.

Isaac Cooke Thompson in 1895. From Herdman, “Proceedings and Transactions of the Liverpool Biological Society”, 1903.

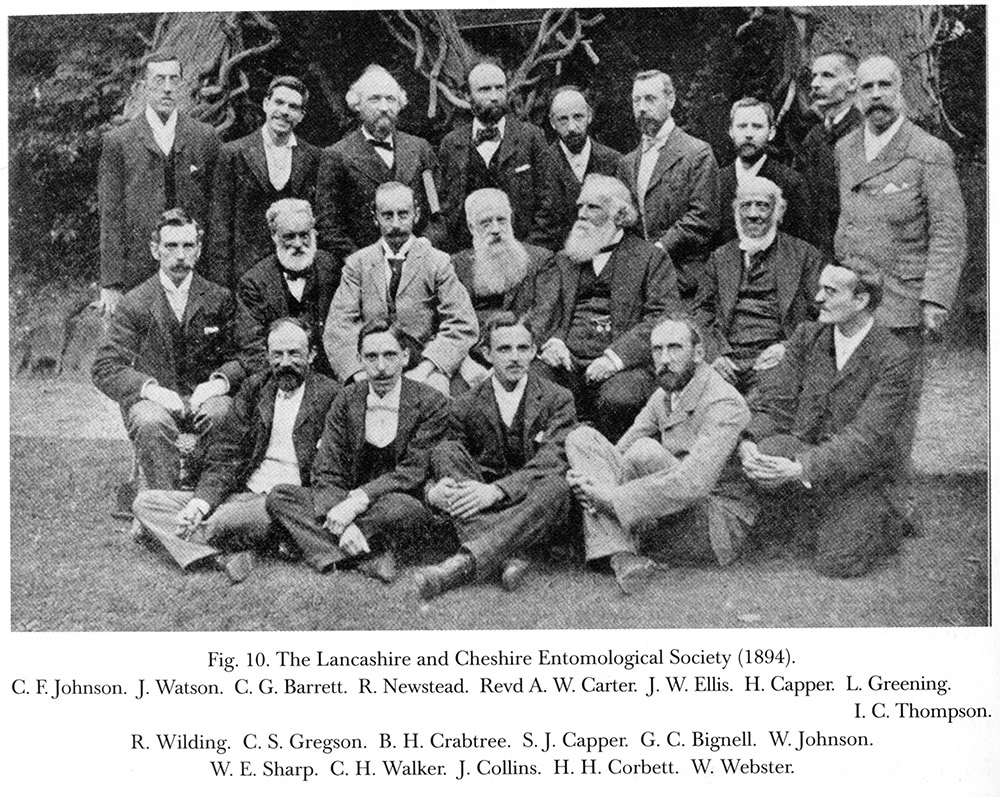

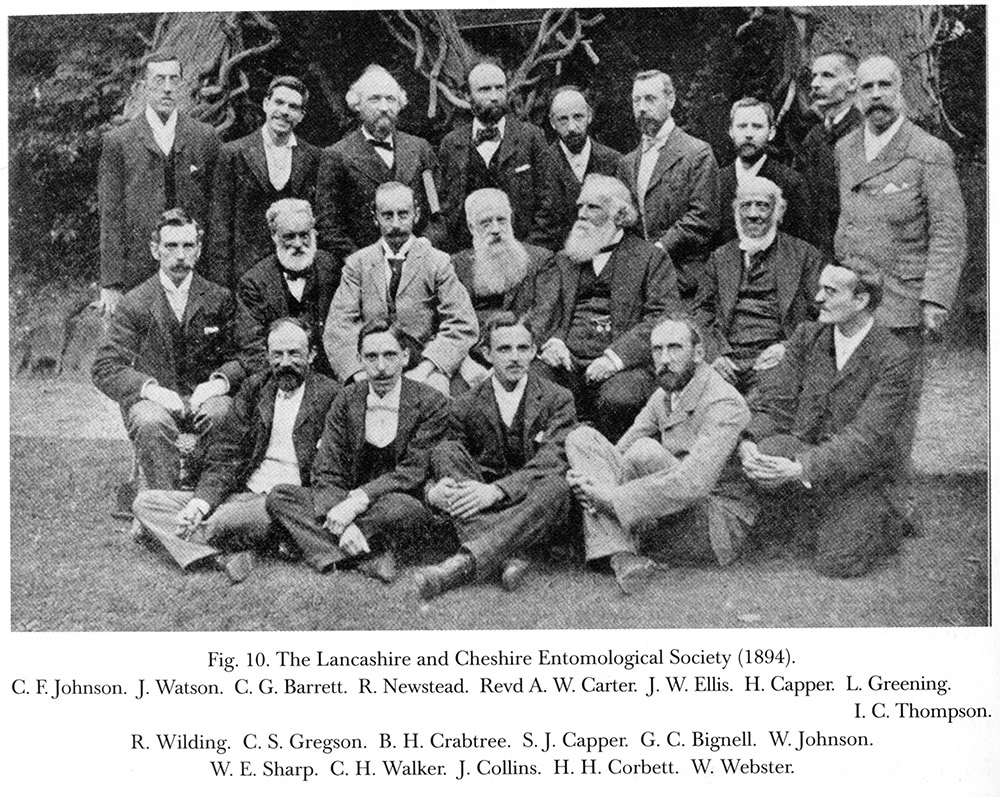

Figure 10.

Isaac Thompson and other members of the Lancashire and Cheshire Entomological Society in 1894. From Salmon and Edwards’ “The Aurelian's Fireside Companion”, 2005.

The life of Isaac Cooke Thompson was best described by his friend, Sir William Abbott Herdman (1858-1924), in a 1903 memorial that was published in The Proceedings and Transactions of the Liverpool Biological Society:

"In the death of Mr. Isaac C. Thompson last November, at the comparatively early age of 60, the Biological Society loses one of the founders, a constant member of Council and a past President, the L.M.B.C. a devoted Hon. Treasurer and business-head, and Liverpool a much esteemed and helpful citizen, who will be greatly missed in connection with various scientific and educational organisations. His scientific comrades will probably wish to have some record of the leading events of his active life, and his many business and social friends may be interested to know what he did for biological science in Liverpool. I am indebted to Mrs. Thompson, to his sister (Miss Frances Thompson) and to his brothers (Mr. W.P. Thompson and Mr. G.E. Thompson) for some of the particulars and dates previous to about 1880, when I first met my friend.

Since 1881 I have been privileged to enjoy a very close companionship with Isaac Thompson, both in town and country, over our microscopes and books in the winter evenings, and on sea and moorland during vacation expeditions. The Sunday before his death, as on many previous Sunday evenings, we met and spent some time together over scientific work, and before we parted walked up and down Ullet Road planning our next expedition to Port Erin. He remarked more than once how he was looking forward to it. A few days later his happy and useful life was suddenly closed by an apoplectic attack which struck him down as he was leaving for business in the morning and terminated fatally in a few hours. He was thus active to the last both in science and business; he had a large piece of scientific work in the printer's hands, and many interests. and concerns on his mind. He died, if any one did, in harness, and his death, coming thus suddenly in the midst of his various activities, leaves a gap in many relations of life which it will be difficult, if indeed possible, to fill.

The family of Thompson, I am told, was one of that rapidly disappearing class, in Westmorland, called ‘statesmen’, viz., farmers cultivating their own land, during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Near the end of the latter they also took to banking, but about 1800 a fire burnt down the bank, with a large number of securities, and ruined the family. Thomas Thompson, the eldest son, at that time a student of medicine in Durham University, at once took the coach to London, in the hope of getting employment. On the coach he got into conversation with William Allen, F.R.S., of Allen and Hanbury, the chemists, whose assistant he became, and at whose house he met James Phillips, the father of William Phillips, F.R.S., the Geologist.

Some time after this Thomas Thompson married Frances, the daughter of James Phillips, and settled in Liverpool as a chemist, at first in connection, to some extent, with Messrs. Allen & Hanbury. Frances Phillips must have been a remarkably talented lady, and her house is said to have become a literary and scientific centre in Liverpool, especially amongst the Quaker community to which they belonged. Her second son. George, after receiving a medical education, succeeded to his father's business - in which, after it had become Thompson & Capper, his second son, Isaac, eventually became a partner. The ancestry thus shows considerable scientific and medical tendencies through several generations.

Isaac Cooke Thompson was descended from old Quaker families on both sides, and has been closely connected with Liverpool by business, social, and scientific ties during the last sixty years. He was born on the 27th July, 1843, at Elm Cottage, a quaint old house which, with its garden and aged mulberry trees, then on the outskirts of Liverpool, has long since been swept away by the inroads of bricks and mortar. When his paternal grandfather, Thomas Thompson, came from London and started the business of chemist and druggist just below what is now the Pro-Cathedral in Church Street, it was thought to be too far from the centre of the town.

Thomas Thompson is described as being an interesting man, with antiquarian tastes. He and the maternal grandfather, Isaac Cooke, of West Derby, who was for long head of the Liverpool firm of cotton brokers, ‘Isaac Cooke & Sons’, were both members of the Society of Friends, in which they occupied leading positions. Their respective son and daughter, George and Eliza Thompson, both had marked ability and showed intellectual tastes. Simplicity of life is said to have been one of the chief characteristics of the home, and the children were encouraged in their love of outdoor life, rambles in the woods and fern collecting being amongst their chief delights. Isaac was the third of six, and they are described as being all high-spirited, fond of adventure, and at times mischievous, but perfectly truthful and obedient children. There are various tales of the pranks and exploits of the four sons, but probably other families of active boys have done much the same.

Isaac was educated first at a boarding school at Kendal, and then went for a couple of years to the Friends' School at Bootham, York, where his uncle, the father of Professor Silvanus Thompson, was one of the masters. There, probably, his love of Natural History received a fresh impetus, this school having always given considerable attention to the study of science. An old schoolfellow, now Dr. Nicholson, of Clifton, writes: ‘His chief characteristic was his enthusiasm for everything he put his hand to. I recollect how he put life into the Natural History Society when he became secretary. He seemed to me to have a special bent towards Natural History when I knew him so well’. He left York in consequence of a severe illness, and afterwards finished his education at the Liverpool Institute.

In the meantime his father had established the business of homoeopathic chemist, and on leaving school, in 1858, he was apprenticed to the firm of ‘Thompson and Capper’, in which he afterwards became a partner. In the early sixties he attended classes in science at the Liverpool Royal Infirmary School of Medicine, which afterwards became the Medical Faculty of University College. Amongst his teachers at that time were Dr. Cuthbert Collingwood (Natural History), Dr. Nevins (Botany), and Dr. Birkenhead (Chemistry) and Thompson, we know, distinguished himself, amongst other subjects, by his attainments in Botany, and was indefatigable in the formation of a large herbarium of local plants, for which he obtained a special prize. The search for rare specimens led him to explore minutely the district around Liverpool; and it was then he took the longer walks in Scotland and into North Wales, which he used sometimes to recall. I have heard of his doing over sixty miles in the day. It is of this time that Dr. Nicholson writes:

‘We had several pursuits in common, and one was the long walks you refer to. We walked fifty miles together to Rhyl, and he was not quite content, and walked several more after getting home. We repeated the same for two years, I think. It did not appear to hurt us, and we were all teetotalers’. Miss Thompson adds to this: ‘A medical man wished to see Isaac, and expressed his concern at his taking these long walks. Isaac naturally asked, Why? as he did not feel any the worse. Whereupon the doctor said he must have to take doses of brandy towards the end of the walk to keep up his strength; but on hearing that he was a teetotaler, he had nothing more to say’.

Thompson remained an active man all his life, and being for the most part in vigorous health, was addicted to many forms of healthy exercise-climbing, cycling, rowing and swimming. He ascended Mont Blanc and Monte Rosa in 1868; and when in the country was keen to get to the tops of all the hills in sight. He was always fond of sea-bathing, which he would indulge in at any hour of the day or night, and sometimes, during holidays at the sea-side, several times in the day. It was his regular custom, when on scientific expeditions at Puffin Island or Port Erin, to begin the day with a plunge and a swim before breakfast, and no weather deterred him. The present writer has been routed out of bed and conveyed off to bathe by his friend more than once in December and January, over ground covered with snow.

He is said to have been the first in this part of the country to ride the bicycle. His brother George writes to me: 'I believe it was in 1865 that he read of bicycles being made in Paris. He and I went to Mr. Thomas, carriage builder, in St. Anne Street, Liverpool. Thomas said that he had not seen one, but could build one, and he soon did so. There were two light wooden carriage wheels of nearly the same size, the larger (front one) being twenty-three inches in diameter. A heavy spring, nearly three feet long, supported the saddle. The pedals were of solid brass, triangular in shape. The wheels being small gave an idea of speed, but I do not think that it ran above eight miles an hour. When it came home, I said I would have a larger one, and ordered it to have a front wheel of twenty-five inches. A fork in front supported the legs when going down hill. I rode through Perthshire on mine in company with my younger brother, Edwin. The folk ran from the fields to see us pass. Such was the old bone-shaker'.

Isaac Thompson was an active cyclist to the end, and in recent years made several pleasant cycling tours with members of his family, both in this country and abroad. He keenly enjoyed travel in foreign countries, and everywhere he went had an eye to the Natural History, brought back specimens, and met interesting friends. He travelled through Norway in early days, was in Switzerland in 1868 - where he met Professor Tyndall, and returned with him through France - visited the United States and Canada in 1876 - when he was much interested in the exploration of the Mammoth Cave of Kentucky - and again in 1884, when he went through the Yellowstone National Park with his friend, Sir Oliver Lodge; traversed the Mediterranean, for the first time, in 1877, and made interesting remarks in his diary as to the Physalia, and other forms of surface life, that he observed; did the Pyrenees in 1880, Donegal, Holland, Germany, Austria, &c., in the eighties, and made several other visits to Italy, France, Switzerland, Greece, Palestine, and Egypt since. In 1896 he called upon Claus in Vienna, and seems, from his diary, to have had a pleasant visit, with some discussion on Copepoda. The Prince of Monaco invited him, in June, 1889, to his house in Paris, where he met Baron de Guerne and other French Zoologists, and was much interested in hearing from them of the tow-nets and other oceanographic collecting apparatus used on the Prince's yacht. A trip to the Canary Islands, in 1887, with Mr. Macmillan, yielded some zoological material upon which papers were written, to be referred to below. Many of the acquaintances made on these travels ripened into friendship, and he had latterly interesting scientific correspondents in many parts of the world.

Dr. Nicholson, writing of him as a student, says: 'His geniality and great simplicity of character made him a host of friends; and he seems to have retained this quality just the same as in old days. The ‘old days’ were when he was starting his business life in Liverpool, and the same friend writes of that time: ‘After studying science, he had a great wish to begin medicine. I tried to dissuade him from this, for I thought he could not do both well. The desire continued for a long time, I think. Of course he would have made a successful practitioner, but probably he did much better work as it was’.

In 1867 his younger sister died, after an illness of two years which Isaac did much to lighten and cheer by his improvised fairy tales and bright stories of the imagination. Her death was followed in two years by that of his father, and in one more by that of his youngest brother, Edwin, at the age of 22, just on the completion of his medical course at Edinburgh. This brother's career had been one of great promise, and these successive breaks in the family circle were keenly felt, and are said to have left an impress on Isaac Thompson's mind and character. On June 1st, 1870, he married Susan, the youngest daughter of Joseph and Agnes Stevens, Liverpool Friends. They went to Switzerland for the wedding tour, returning through Paris just before the siege.

Thompson's early scientific studies led him first into Botany, and then to the microscopic study of the lower plants, and so to the lower fresh-water animals and ‘Pond life’ in general. He became an accomplished microscopist at a time when Liverpool was distinguished by having Dallinger and Drysdale carrying on their important investigations into the life-history of the lowest organisms. At that time, thirty years ago, he was a Fellow of the Royal Microscopical Society, and held successively the posts of Secretary and President of the Liverpool Microscopical Society. Soon after, when Mr. Dallinger had left Liverpool, and Dr. Drysdale was no longer an active worker, Mr. Thompson came to be recognised as the leading local authority on the microscope.

He was a prominent member of several of the scientific societies, and along with the Rev. H.H. Higgins, Mr. T.J. Moore, and other local Naturalists, he took a leading part in organising the ‘Associated Soirée’ of these societies, which was held each winter in St. George's Hall until about 1884. It was at one of these gatherings, in December, 1881, that the present writer first met Isaac Thompson, and other members of the ‘Microscopical’ and ‘Literary and Philosophical’ Societies; and when a few weeks later, in January, 1882, University College opened, a couple of these local Naturalists very kindly came to give a welcome at his first lecture to the young and inexperienced Professor of Natural History. I well remember, and can recall, amongst the sprinkling of students, the serious but kindly face, largely covered with, at that time, a dense black beard. At the end of the lecture he joined me, with pleasant remarks, and invited me to his house in Waverley Road. From that time we were close friends, and our intercourse has been very constant and very intimate both in Liverpool and on expeditions, and in country quarters, such as Bute, Arran, Tarbert and Wales, during the last twenty-two years. I found him an ardent field-naturalist, with a wide general knowledge of biology, and a specialist's acquaintance with the construction and use of the microscope. He was ready for the more serious original scientific work to which he presently turned. His position at that time in the local scientific circles was fitly indicated by his selection, in April, 1882, to attend Darwin's funeral in Westminster Abbey as the representative of the Liverpool scientific societies.

A few years later Thompson was one of the founders of the Biological Society and of the Liverpool Marine Biology Committee, and it is in connection with the latter, and during the last twenty years, that most of his original scientific work has been done. It has long been a characteristic feature of English science that really distinguished work has come, not only from those professionally engaged, but also from serious amateurs-men who have the scientific spirit and training, but do the work solely for the love of research, and for the intellectual interests and the aesthetic beauties of nature which their investigations reveal. This has been especially the case in Natural History, and Thompson was one of these serious amateurs who did good work of lasting value. Like Dr. George Johnston, Alder and Hancock, Hincks, H.B. Brady, and Gwyn Jeffreys - to mention only a few of those who preceded him - Isaac Thompson made contributions to our knowledge of the marine fauna which, taken with the scientific memoirs of these other amateurs, constitute one of the glories of British Zoology.

In taking up a subject for serious study in connection with the L.M.B.C. investigations, he soon acquired a wide acquaintance with the Crustacea, and an intimate detailed knowledge of the Copepoda and some allied groups of Entomostraca. He never claimed to be a morphologist, in the modern academic sense, or to go into minute histological structure; but he was a good type of the cultured field-naturalist, and of a systematist of the bestkind, interested in the lives and habits of his animals, and preferring to catch the specimens himself, and to examine them in the first place alive. He was always a prominent member of the party during our dredging expeditions in Liverpool Bay, and at the Port Erin Biological Station. Little more than a month before hist death he was one of the leaders in the British Association dredging excursion, which followed the Southport meeting. His special function on these occasions was to take charge of the tow-nets, and any who have been out with the L.M.B.C. will recall his familiar figure sitting at the stern with the rope in his hand, or emptying his net into a wide-mouthed collecting-jar, or it may be examining his catch with a lens, as shown in the accompanying cut-it is unfortunately taken from a very poor photograph (of 1892) but it is of interest as recalling to some of us our friend at work. Another familiar and favourite pursuit of his, tow-netting from our little ‘shell-bend’ punt in Port Erin Bay, may be recalled by this figure taken from a photograph by his son, Edwin Thompson, in 1898. We had just landed on the flat sand below the old Biological Station, and the tide had run out and left us.

On expeditions he was indefatigable as a collector, and seized every opportunity when the steamer slowed down, even temporarily, to get his net overboard, and secure at least a dip; he washed our dredged sand, mud and debris through sieves and gauze bags to separate the minute bottom-living Copepoda, and he opened the molluscs and fish that we trawled to examine them for parasitic forms. I have seen him secure some good specimens from the gills of fish in passing through the fish market at Douglas, on the way from the steamer to the train. His pockets seemed always to contain little bottles and tubes, into which specimens could be popped; and the result of all this was that he rarely went out without finding something, and nearly every expedition yielded new species or specimens of great interest. It was a common occurrence for him to ring me up on the telephone on a Sunday afternoon to announce what he had just found under the microscope, as the result of Saturday's expedition. He was an accurate worker, and yet a rapid worker. I was often astonished at the amount of work he got through in the scanty leisure of an active business life. He had, I consider, a good eye for species. His critical remarks both on those who split up species unduly and on those who fail to recognise the differences between allied but distinct forms were valuable, and he showed a sound, reliable judgment on the essential characters and affinities of the new forms he discovered.

Thompson's early papers on the Copepoda dealt with the species found in Liverpool Bay and other parts of the Irish Sea, and in 1893 he published a ‘Revision’ of our local Copepoda, with twenty-one plates, in which 136 species, of which eighteen were new to Britain and eleven new to science, are recorded. The number was increased, as the result of his own work and that of Mr. Andrew Scott, to 246 species in his Southport British Association list of 1903. As the result of his own and his friends' vacation travels, however, he also published papers on the Mediterranean and Norwegian species, and on collections from the West Indies, Madeira and the Canaries, the West Coast of Ireland, the Faeroe Channel, and a traverse through the North Atlantic to Quebec. He also described Copepoda from the Bay of Bengal, the Antarctic, the Red Sea and East Coast of Africa, and recently from the ‘Oceana’ expedition in the North Atlantic. As a complete list of his published. works will be appended to this Memoir, further particulars need not, perhaps, be given here; but I may add that in these papers he described many new forms, aided in the elucidation of not a few obscure points, and greatly extended our knowledge of the geographical distribution of the group.

Thompson's last piece of scientific work was a large report, undertaken jointly with Mr. Andrew Scott, upon the Copepoda of the Ceylon Pearl Banks, recording 283 species, of which seventy-six are described as new to science. This extensive work has since been published by the Royal Society; it was completed during October, and the last of his sheets were passed for press a few days before he was struck down. It has been referred to by one who saw the proofs as the pioneer work on tropical Harpacticidae and Lichomolgida. Thompson's papers have been published for the most part in the Transactions of the Liverpool Biological Society and the Reports of the L.M.B.C., the Journal of the Linnean Society, the Annals and Magazine of Natural History, and the Reports of the British Association. But there was much of his information that he did not publish. He was so naturally kind and liberal that all that he knew, and all the specimens he had, were always at his friends' disposal. For example, he sent his single specimen of Artotrogus orbicularis, found at Puffin Island, to be described and figured by Giesbrecht in his Naples monograph on the Asterocherida. He was in correspondence with Claus, Richard, Giesbrecht, Brian, Poppe, Canu, and other Continental workers, and frequently supplied them with British specimens required for comparison or for description in their monographs.

This original and special scientific work did not, however, represent all his work for Science. There were few of our local organisations for the advancement of science, and the application of scientific teaching, in which Mr. Thompson did not play a prominent part. Although fully occupied as an active man of business, with many concerns on his mind and hands, he found time to help on good work on very varied lines. Few men had more appeals for lectures, for papers, for help in organising, for his services (which were always highly valued) as Hon. Treasurer of funds, as member of Council or Committee; and never in the experience of some of us were such appeals made to him in vain. He has discoursed with equal success on the wonders of Nature in the lecture theatres of the University and the mission. halls of the slums, and many in Liverpool must have heard him expound, either at scientific meetings or in conversation, the importance of Biology to man, and the value of his minute crustaceans both as the food of many fishes, and also as scavengers of the sea.

He took a keen interest in educational matters, and held advanced views as to the teaching of science to the young, and the exclusion of religious instruction from schools. He was Treasurer of the Hope Street Unitarian Schools for twenty years, until they were taken over by the new authority under the recent Education Act. His interest in the progress of University College and the establishment of the University has been unfailing. He was delighted at the provision made for local marine biology, both in laboratory and museum accommodation, in the Natural History building now in course of erection. Soon after the opening of University College, at a time when it was badly needed, he kindly gave a small donation for the provision of books for the biological department; and it is pleasant to think that arrangements are being made whereby his own library of marine biology will be deposited in the departmental library of our new buildings for the use of the workers who follow in his footsteps, and to keep alive his name in connection with the subject for which he did so much.

Thompson was a fellow of the Linnean Society, and sometimes attended the meetings; although for the most part he was too busy in Liverpool to take an active interest in London scientific societies. But he was a regular and useful member of Section D (Zoology) at British Association Meetings. He has served on various Committees of the Association, and has taken part in the preparation of several Reports. On the occasion of the last visit of the British Association to Liverpool, in 1896, Thompson was one of the Local Secretaries, and his colleagues, the other local officers, can testify how well he did his share of the hard work, and how much the success of that great meeting depended upon his admirable business arrangements and careful attention to detail.

Although a Quaker in early life, he afterwards severed his connection with that community, and joined the Unitarians. Of late years he attended the Ullet Road Unitarian Church. He took much interest in the investigation of telepathy and allied phenomena carried on by Lodge and others, and attended many of their meetings and sittings. He was a member of the Psychical Research Society for some years.

Mrs. Thompson, three daughters and a son-all grown up-survive him. The portrait at the beginning of this Memoir is from a photograph by his son, Edwin Thompson, taken in 1895.

The progress of Natural History investigation in this district during the last quarter of the nineteenth century will ever be connected with a few names, such as H.H. Higgins, T.J. Moore, and Frank Archer; and amongst that little band of workers-some others of whom are happily still with us - the name of Isaac Thompson holds an honourable position. His loss will be keenly felt both by many in Liverpool, where his work chiefly lay, and also by the large number of scientific men throughout the country who were his personal friends, and had learned to appreciate, not only his scientific knowledge and skill, but also his honest, fearless, upright character and his bright and sympathetic loving nature. The loss to science is great, the loss to Liverpool of the man doing his duty nobly and full of good works is greater still; and of the loss to those who were privileged to enjoy his friendship, or to be united with him by still closer ties, it is impossible to speak.”

____________________________________________________________

Additional memorials:

From The Journal of Concholoy:

"The Society, in common with the scientific world at large, has to deplore a serious loss in the person of Mr. Isaac C. Thompson, of Liverpool, who was suddenly struck down by apoplexy in full vigour only five days ago. He was born at Birkenhead, in 1843, and descended from a family well and honourably known in the Society of Friends. His mother was one of the ministers of that body, and both for her character and discourses much valued by the Liverpool meeting. He inherited his scientific tastes from his father, who was a member of the old-established firm of Thompson and Capper, pharmaceutical chemists, and was fond of assembling a number of congenial friends around him to spend the evening in studying specimens with the microscope. If report speaks truly these gatherings had a well-developed social as well as a scientific sidw.

Isaac Thompson was educated at Kendal, and subsequently at York, and then, on leaving school at the age of fifteen, was sent into his father's place of business. At this time his chief scientific interest was in botany; he was passionately fond of flowers, and so successful as a collector that he won a prize offered by the Liverpool Royal Infirmary for the best series obtained in the neighbourhood of that city. It is recorded in the family annals that being sent one day on a message to Lord Derby's house, he picked on the way all the flowers not previously known to him, mostly what would be termed weeds. Not wishing to appear at the door with these treasures in his hands, he concealed them until his return. His surprise may be imagined when two ladies of Lord Derby's family called at the shop next day with a choice bouquet for "the young man who was so fond of flowers." Eventually he became a partner in the business, and on his father's death, at the age of fifty-seven, took a very active share in the management of the firm.

Turning to Thompson's scientific work, that for which he will best be known by posterity will be his long series of papers on the smaller Crustacea, beginning in 1886 with a ‘Report on the Copepoda of Liverpool Bay’, and proceeding steadily and with increasing importance and culminating in a long report on the Copepoda collected by Professor Herdman in Ceylon—a monumental work occupying eighty pages, and illustrated by twenty plates, undertaken in collaboration with Mr. Andrew Scott, and, by a curious coincidence, sent to press on the very day of his death.

Isaac Thompson was not, however, a mere specialist among minute Crustacea; he was a naturalist of extensive knowledge and broad sympathies. In conjunction with his friend Dr. Herdman, he took an active part in the foundation and subsequent management of the Liverpool Marine Biology Committee, founded for the systematic investigation of the fauna of the district. He filled for years the important office of treasurer, watched over its small beginnings in the Marine Laboratory on Puffin Island, and eventually saw it installed in more commodious premises at Port Erin.

He was also an original member of the Liverpool Biological Society, and was recently elected to its Presidential Chair. His interest in science was, however, even wider than that of the naturalist pure and simple: he had a sympathy with, and understanding of, the problems of physical science, and was one of the founders of the Liverpool Physical Society.

But he was more than a scientist: he was intensely human in all his thoughts and feelings; full of warm sympathetic interest in all that concerned the welfare of his fellow-men. In him we have lost at one blow the earnest student of nature, the sound financier, the active clear-minded administrator, the sympathetic neighbour, and the truehearted comrade. What wonder, then, that his friends and colleagues feel the loss a heavy one.”

From The Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London:

“Isaac Cooke Thompson was born July 27, 1843, became a Fellow of the Linnean Society Dec. 1, 1887; died Nov. 6, 1903. He was a chemist by profession and a naturalist from his boyhood. As a young man he attended classes in science at the Liverpool Royal Infirmary School of Medicine, distinguishing himself by his attainments in botany, and industriously forming a large herbarium of local plants, for which he obtained a special prize, In those days he would walk fifty or sixty miles a day in search of rare specimens, and being a teetotaler he accomplished these long distances without recourse to stimulants. He was a great traveller by land and sea; an ardent hill-climber, ascending Mont Blanc and Monte Rosa in 1868; a vigorous athlete in many exercises, with a special devotion to swimming. "It was his regular custom, when on scientific expeditions at Puffin Island or Port Erin, to begin the day with a plunge and a swim before breakfast, and no weather deterred him." Professor Herdman, from whose memoir most of these facts are taken, "has been routed out of bed and conveyed off to bathe by his friend more than once in December and January, over ground covered with snow." One may perhaps sorrowfully reflect that Thompson trusted too far to an iron constitution, and made demands upon it beyond what even the most rigid temperance in other respects could justify. His mental activity matched his physical powers of endurance. Thirty years ago he was already an accomplished microscopist. He held successively the posts of Secretary and President of the Liverpool Microscopical Society, coming to be recognized, in succession to Dallinger and Drysdale, as the leading local authority on the microscope.

Along with Herdman, A.O. Walker, and others, Thompson was one of the founders of the Liverpool Biological Society and its Marine Biology Committee. It is in connection with the latter, and during the last twenty years, that most of his original scientific work has been done. In that period he acquired a wide acquaintance with the Crustacea, and an intimate detailed knowledge of the Copepoda and some allied groups of Entomostraca. His ‘Copepoda of Madeira and the Canary Islands, with descriptions of new genera and species’, was published in our own Journal in 1900 (vol. xx.), but, as was natural, a long series of his papers appeared in the Transactions of the Liverpool Biological Society. From time to time the Journals and Proceedings of other Societies contained essays from his pen, generally on the same favourite subject of the Copepoda. Just before his death he had completed, in partnership with Mr. Andrew Scott, A.L.S., an important Report upon the Copepoda of the Ceylon Pearl Banks, for Herdman's great work on the Pearl Oyster Fisheries of that island, now in course of publication by the Royal Society. The impression produced by I. C. Thompson on those who him only at irregular intervals fully agrees with the opinion expressed by his intimate friend. He seemed to be a man of solid worth, without caprice of temper, uniformly actuated by genuine kindness. His biographer speaks of the large number of men, well qualified to judge, who "had learned to appreciate, not only his scientific knowledge and skill, but also his honest, fearless, upright character and his bright and sympathetic loving nature."

From Nature:

“Liverpool has lost a well-known naturalist in the death of Mr. I.C. Thompson, who was hon. treasurer of the Liverpool Marine Biology Committee from its foundation nearly twenty years ago. He had a wide knowledge of the Crustacea, and, especially of Copepoda, the group upon which most of his original work was done, but he was also a keen field-naturalist, interested in the lives and habits of his animals, and preferring to catch the specimens himself and to examine them in the first place alive. He was always a prominent member of the party during the dredging expeditions in the Irish Sea and at the Port Erin Biological Station. Little more than a month before his death he was one of the leaders in the British Association dredging excursion which followed the Southport meeting.”

Figure 11.

A chest of homeopathic concoctions by Thompson & Capper. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

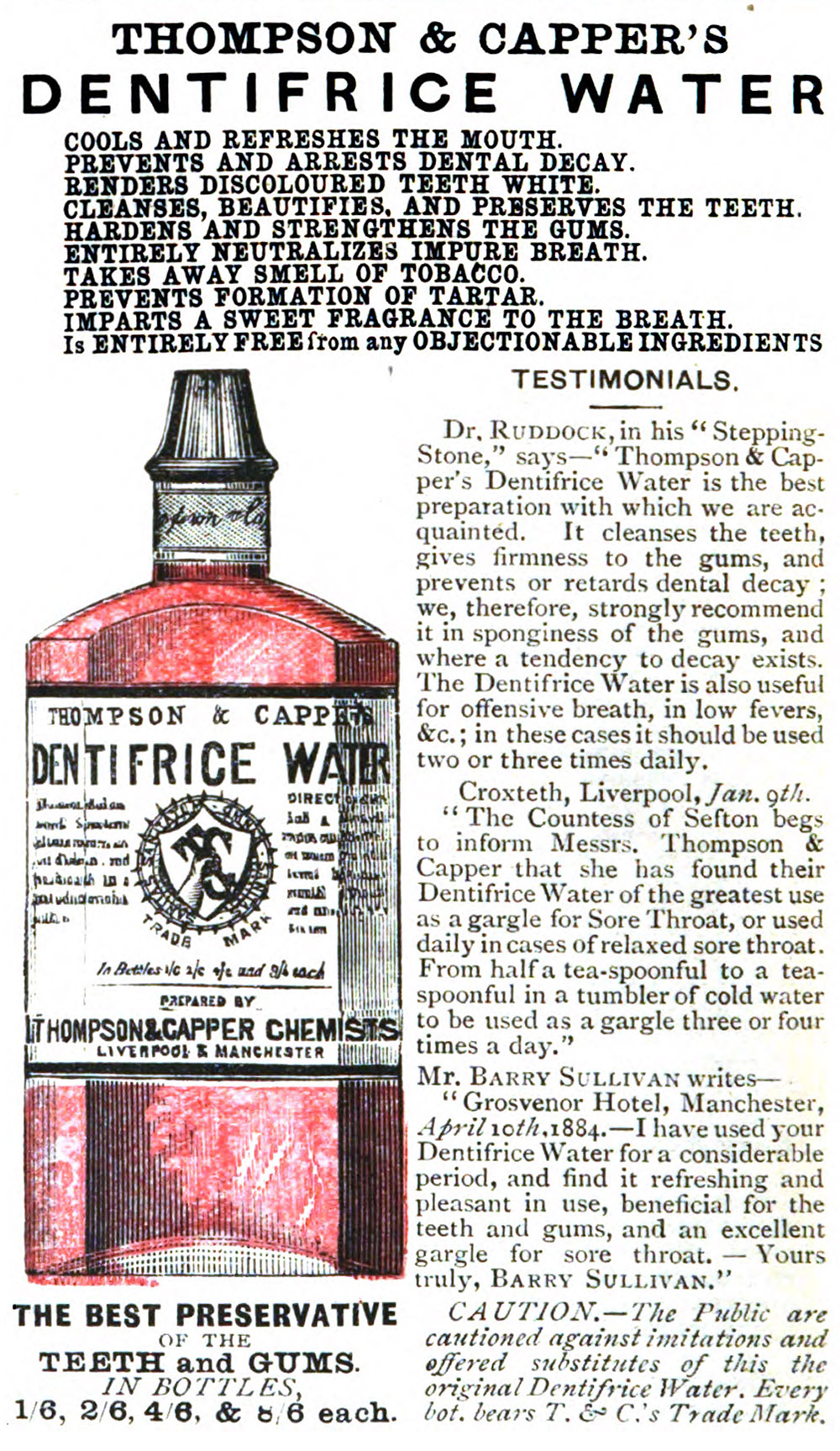

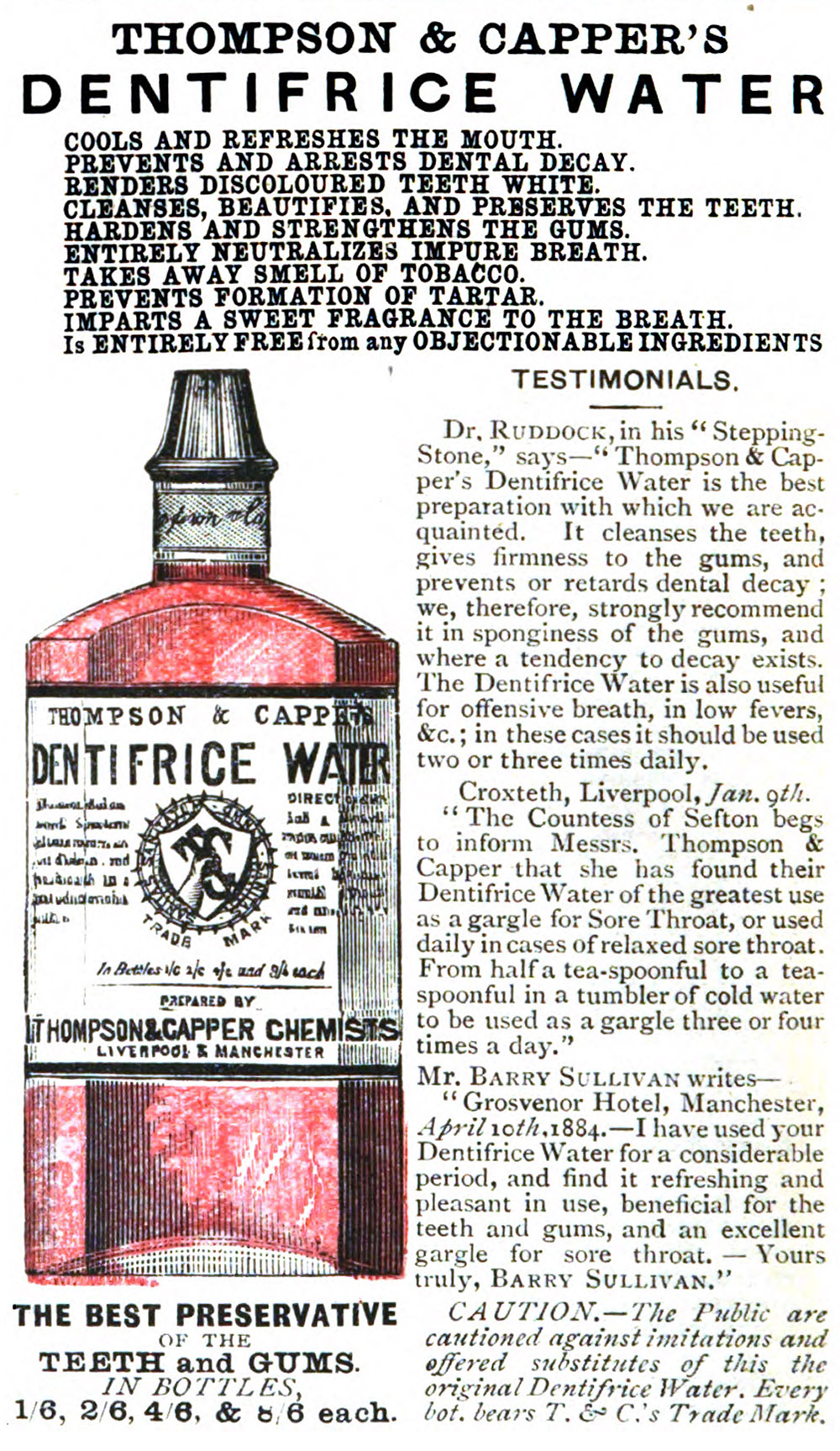

Figure 12.

An 1887 advertisement for “Thompson & Capper’s Dentifrice Water”. From Hayward, “Taking Cold”.

Acknowledgement

Thank you to the late Peter Paisley for sharing results of research on J.W.D. Hume and his connections to Thompson & Capper.

Resources

Bracegirdle, Brian (1998) Microscopical Mounts and Mounters, Quekett Microscopical Club, London, pages 93 and 184, Plate 40-R

Davis, George Edward (1882) Botterill’s trough and life-slide, Practical Microscopy, pages 87-88

England census and other records, accessed through ancestry.com

English Mechanics and the World of Science (1885) Liverpool and District Association of Science and Art Teachers, “much time was spent in the practical examination of microscopes, apparatus, and specimens … and several students' microscopes and apparatus sent by Messrs. Thompson and Capper”, page 210

Hardwicke's Science-Gossip (1876) Exchange offer from I.C. Thompson, page 24

Hardwicke's Science-Gossip (1878) Exchange offer from I.C. Thompson, page 264

Hardwicke's Science-Gossip (1889) Advertisements from Walter White, advertising sections of numerous issues

Hayward, John William (1888) Taking Cold (The Cause of Half Our Diseases): Its Nature, Causes, Prevention & Cure, Seventh edition, E. Gould & Son, London, Advertisement from Thomson and Capper

Herdman, W.A. (1903) Isaac Cook Thompson, F.L.S., a brief memoir, Proceedings and Transactions of the Liverpool Biological Society, pages 45-62

Hoyle, W.E. (1903) Isaac Cook Thompson, F.L.S., Journal of Conchology, pages 14-15

Journal of the New-York Microscopical Society (1888) Minutes of the October 12 meeting of the San Francisco Microscopical Society, “A letter was read from Mr. Isaac C. Thompson, F.R.M.S., of Liverpool, England. Mr. Thompson desires to secure material for the study of minute crustaceans, a special line of investigation which he has pursued for some time, and upon which he has made valuable reports to the Liverpool Microscopical Society. His letter prescribed the following as a solution best fitted to preserve specimens of marine life: Water, one part; proof spirits, two parts; glycerine, one part; with one per cent. of carbolic acid added. By securing gatherings from the Pacific Mr. Thompson hopes to add to his previous finds of new Copepoda. In an expedition to the Canary Islands he captured from forty to fifty new species. The San Francisco Society will endeavor to obtain the material desired”, page 95

Journal of the Quekett Microscopical Club (1887) Members, “May 23, 1879. Thompson, I.C. F.R.M.S., Woodstock, Waverley Road, Liverpool”

Journal of the Royal Microscopical Society (1889) Fellows: “1880, Thompson, Isaac Cooke, F.L.S., Woodstock, Waverley-road, Liverpool”

MacLaren, Joseph (1911) Fairbairn's Crests of the Leading Families in Great Britain and Ireland and Their Kindred in Other Lands, “Thompson”, page 489

Microscopical News and Northern Microscopist (1881) “The American Monthly Microscopical Journal, The January issue of this Journal is full of interesting matter. The detection of adulteration in coffee-Infusoria on leaves--Mounting with glycerine jelly-Cells, their growth and functions.-A very practical article on The preparation and mounting of microscopical objects. A note on the resolution of A. Pellucida, and studies of atmospheric dust. These articles, together with many paragraphs of interest, as well as the proceedings of about half-a-dozen societies, should make the journal interesting to English microscopists. The subscription is low, and copies may be easily obtained in this country from 4, Lord Street, Liverpool", page 70

Microscopical News and Northern Microscopist (1883) Liverpool Microscopical Society, page 206

Microscopical News and Northern Microscopist (1883) Microscopical labels, page 323

Nature (1879) Advertisement from R. & J. Beck, advertising sections

Nature (1903) Obituary of Issac Cooke Thompson, pages 60-61

The New England Medical Gazette (1875) Progress of homeopathy in Liverpool, “Mr. Isaac C. Thompson (of the firm of Messrs. Thompson and Capper) exhibited in the microscope some preparations of lycopodium sporules, illustrative of its therapeutic value as brought out by long trituration”, Vol. 10, pages 552-553

Paisley, Peter (2012) A bit more about Hume, Micscape, https://www.microscopy-uk.org.uk/mag/artmay12/pp-hume-3.doc (accessed July, 2024)

Probate of the will of Isaac C. Thomson (1903) “Thompson Isaac Cooke of Croxteth-road Liverpool homeopathic-chemist died 6 November 1903 Probate Liverpool 22 January to Susanna Dodgson Thompson widow and George Edward Thompson photographer Effects £10814 19s 8d”, accessed through ancestry.com

Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London (1903) Issac Cooke Thompson, pages 36-37

Radcliffe, John (1898) Note on Thompson family crests, Notes and Queries, page 116

Salmon, Michael, A., and Peter J. Edwards (2005) The Aurelian's Fireside Companion, Paphia, Lymington, Hampshire, page 16

Thompson, Isaac C. (1883) “To the Editor of ‘The Microscopical News’: Dear Sir, My attention has been called to a paragraph in the last number of your Journal, referring to a note in the previous number wherein you appear to have given credit to a Mr. Quinn for bringing out some Micro. Labels, while in the last number you divide the credit between Mr. Quinn and myself. It would certainly appear a rather curious coincidence that two people should separately bring out a set of labels precisely similar both as to special colours and matter of each, and at precisely the same time; and before giving a sketch of each I think you might with advantage have ascertained whether they had not one common origin. To convince our readers that such is the case I can only refer to Mr. Wilkinson, of Pendleton Printing Works, to whom I handed all my original sketches of the labels—three being for myself, and two for the Microscopical Society of which I am Hon. Secretary. Upon enquiry I find that Mr. Quinn saw these labels while in the printer's hands, and that he at once procured almost exactly similar ones, and of the same colours, and I am rather surprised that he should not, through your columns, have corrected your error. I would gladly have sent you copies of these labels at first, but that a full abstract of my explanatory paper, entitled "On the Classification and Labelling of Microscopical Objects," was sent to another paper, where it appears in the present month's issue. And can only add that any one is now at liberty to use similar labels, or to improve upon them”, Microscopical News and Northern Microscopist, pages 334-336

Thompson, Isaac C. (1883) On the classification and labelling of microscopical objects, Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip, pages 249-251

Thompson, Issac, C. (1888) On some Copepoda new to Britain found in Liverpool Bay, Report of the Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, page 734

Thompson and Capper (accessed July, 2024) https://www.thompsonandcapper.com