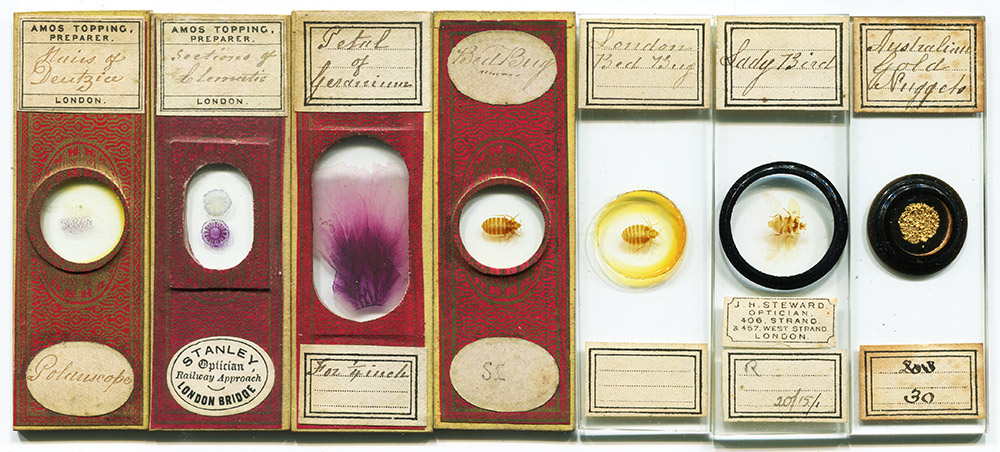

Figure 1. Figure 1. A sampling of microscope slides that were prepared by Amos Topping. Paper-wrapped microscope slides fell out of fashion ca. 1880, so those are presumably his earlier productions.

Amos Topping, 1834 - 1900

by Brian Stevenson

Last updated December 2025

Amos Topping was a son of Charles Morgan Topping (1799-1874), who was one of the most well-regarded preparers of microscope slides during the nineteenth century. Amos began working for his father as a boy. The handwritings of Charles and Amos are readily distinguished, and a fair number of slides with Charles Topping's name bear labels that were written by Amos (and presumably made by Amos). During the early 1870s, before his father's death, Amos began exhibiting his own microscope slides to London societies, suggesting that he had begun an independent business by that time. Amos Topping was considered by contemporary microscopists to be the heir of his father's skills.

"It must be a very poor miscellaneous collection indeed which does not include some, at least, of (Amos Topping's) beautifully neat red and yellow paper-covered slides." George C. Karop, 1900.

"For a period of fifty-seven years (Amos Topping) has sent forth to the world objects of exquisite beauty, much above the average in their freedom from imperfection, and all characterised by great care and neat finish. In every department of his work he was extremely successful.” Frederick W. Watson-Baker, 1900.

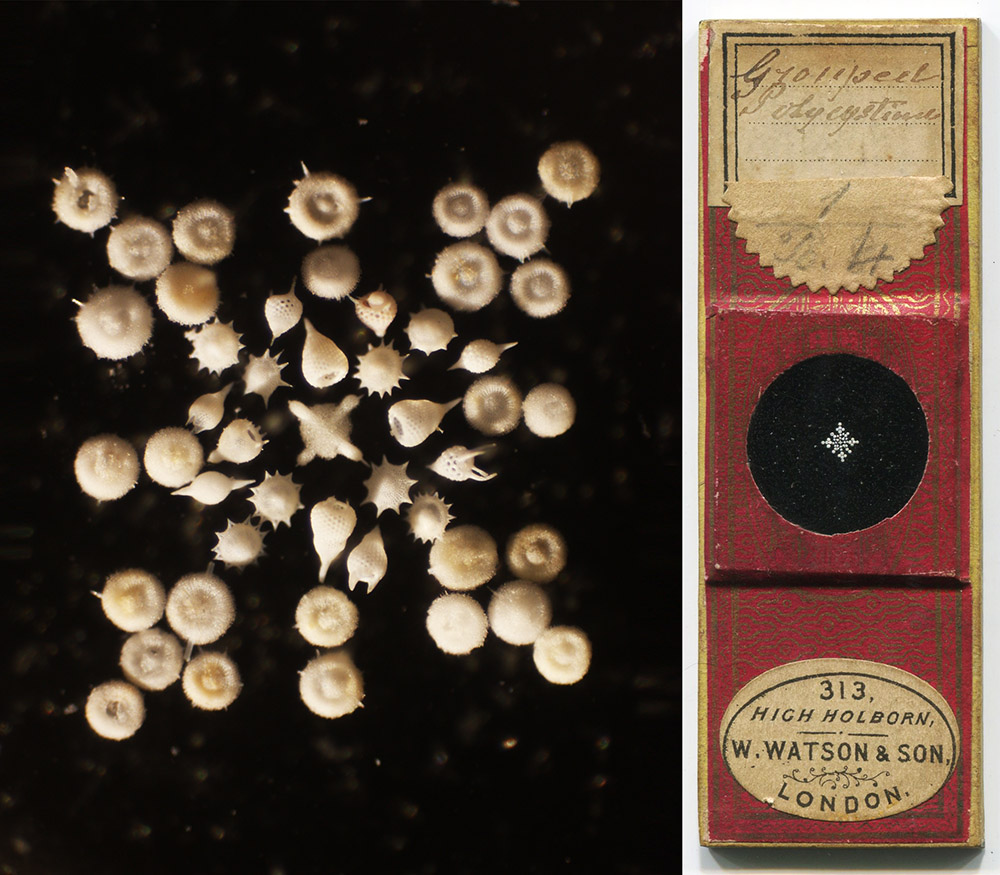

Figure 1.

Figure 1. A sampling of microscope slides that were prepared by Amos Topping. Paper-wrapped microscope slides fell out of fashion ca. 1880, so those are presumably his earlier productions.

Figure 2.

Amos Topping regularly used a gold-on-red patterned paper for the tops of his slides. I have not seen it used by other slide-makers, suggesting that Topping had it custom-printed.

Figure 3.

Amos worked for his father, Charles Topping, for many years before striking out on his own, ca. 1870. It is not uncommon to see slides such as this one, with C.M. Topping’s custom papers and the label written in Amos’ handwriting. Curtesy of Howard Lynk.

Figure 4.

Amos and Charles Topping were both renowned for their mounts of “proboscis of blow fly”. The blowfly’s mouthparts present an intriguing complexity of forms, which the Toppings mounted very flat, such that all components were clearly visible in a plane of view. Frederick W. Watson-Baker wrote about Amos, “he has always been noted for one particular slide, and that is the proboscis of the blow-fly. No other preparer has succeeded in so mounting this subject as to render it sufficiently flat for use as a test-object; and unless some other worker knows the secret, it is likely to become one of the lost arts, and, as we at present know it, a rarity. Mr. Topping was always a little reticent regarding his method of preparing this object, and if he were asked whether he would mind saying how it was done, he promptly replied 'With pleasure, sir', and proceeded as follows: 'I put a piece of sugar upon my bench and hold a blow-fly very closely to it; directly he puts out his proboscis to touch the sugar. I just snip off the tongue with a pair of scissors I keep handy for the purpose, and straightway mount it’."

Figure 5.

Amos Topping regularly sold slides through microscope retailers, sometimes using labels imprinted with the retailers’ information. Most such slides do not give his name, but can be recognized by Amos’ distinctive handwriting. See also Figures 1, 7, 10, 11, 12, and 13).

Figure 6.

A set of small microscope slides, recognizable from the handwriting as having been produced by Amos Topping. They are 2 1/2 x 3/4 inches, 64 x 19 mm, presumably made for a manufacturer/retailer of small drum-type microscopes or similar instruments with small stages.

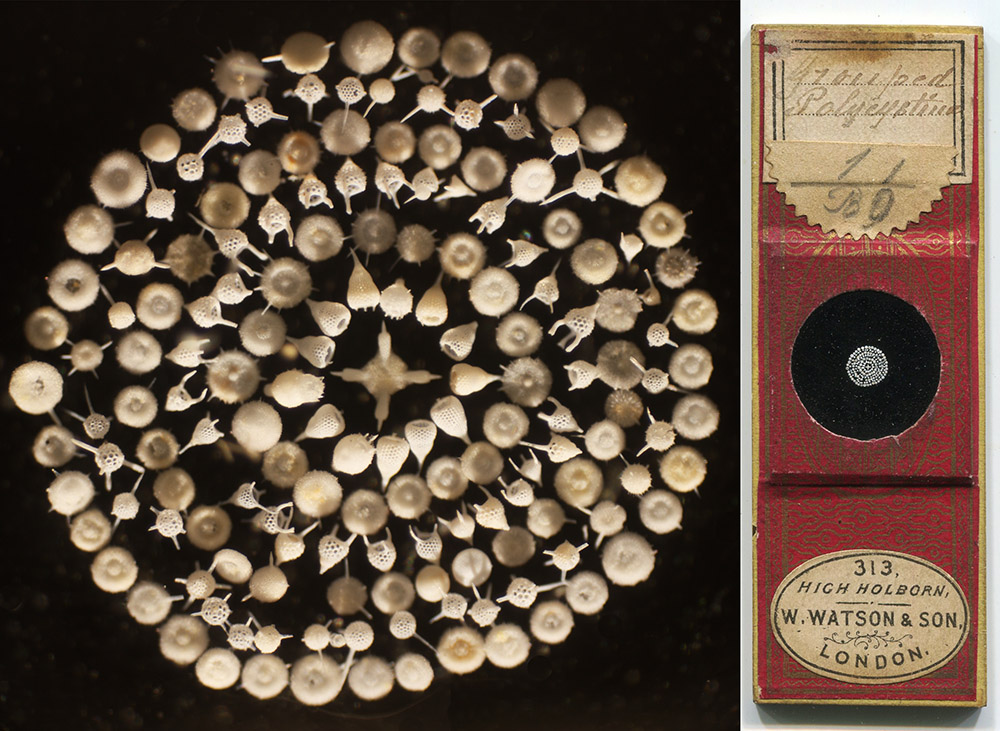

Figure 7.

A set of 1x2 inch slides with Amos Topping’s handwriting, produced for W. Watson & Sons. The set presumably accompanied a microscope or projector that could not hold the standard 1x3 inch format.

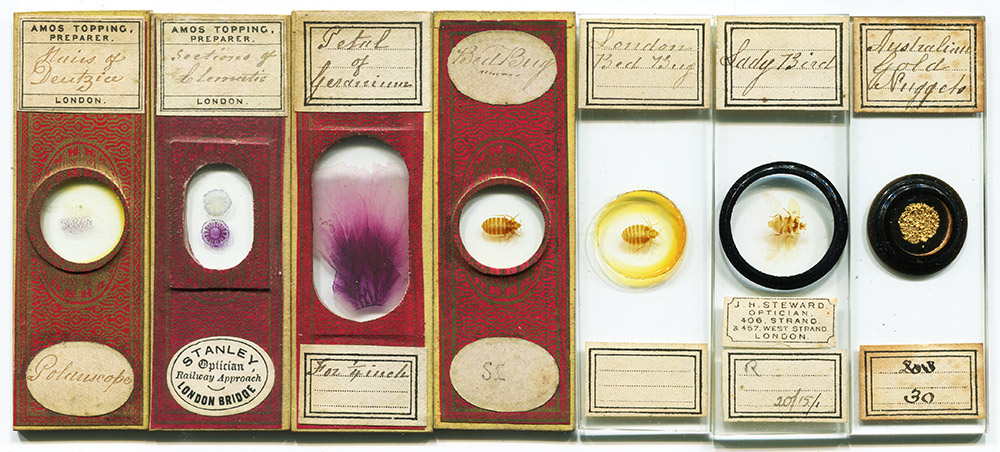

Figure 8.

Amos Topping, from an undated lantern slide. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from the Quekett Microscopical Club.

Charles Morgan Topping began life as a printer, working in the shop that was owned by his father, who was named Amos. Charles inherited the printworks after his father's death in 1817, but sold off the family business by 1828. He remained in the printing business for quite some time after that, evidently as an employee. Two of his subsequent addresses were 10-15 minute walks from the shops of printers who produced books for noted microscopist Andrew Pritchard; if Charles Topping had worked for either of those printers, then he would have met one an important manufacturer of microscopes, and may therefore have been prompted to mount slides for Pritchard’s customers. It is certain that Charles Topping was professionally preparing microscope slides by 1841.

Charles and his first wife, Sarah, had five children: Charles Amos (born in 1827), Sarah (born in 1828), Amos (our microscopist, born in 1831), Harrietta (born in 1837), and Henry (born in 1838). Amos was reported to have begun seriously working with his father at the age of twelve, and all of the children probably worked for their father in his slide-making business to some extent. The 1861 national census reported that Charles Topping employed three workers, who would have been Amos, Henry, and another, as-yet unknown employee (both Amos and Henry were listed as “opticians” in that year’s census). Henry Topping died in 1868, when only 29 years old.

Amos Topping married Sarah Louise Ainge on October 29, 1853. They had three children, all girls.

Amos joined the Quekett Microscopical Club in 1871. During the next year, he exhibited slides to the club, including “injected toe of mouse”, “injected voluntary muscle of frog”, “section of glandular stomach of fowl”, and “section (transverse) medicinal leech”. In December, 1872, he exhibited, “injected bone of kitten, and section of cartilage injected” at a meeting of the Royal Microscopical Society. These steps suggest the beginnings of Amos’ independent business, as QMC membership and displays of his slides would be excellent means of reaching potential customers.

Amos’ mother, also named Sarah, died during the early-mid 1860s. His father, Charles, then moved in with his other wife and their family. It appears that Amos, his mother, and siblings were not previously aware that Charles Topping had a second wife, Emma, with whom he had six children since the mid-1850s. This may have prompted Amos to distance himself from his father and form his own business.

Charles Topping died in September, 1874. He was buried in a common grave like a pauper, further indication of alienation between Amos and his father.

By 1875, Amos Topping’s microscopical preparations were rated among the best in the country, “Among the English preparers, Barnett, Cole, Enock, Norman, and Amos Topping take the lead in their specialities” (English Mechanics and the World of Science).

In 1883, The American Monthly Microscopical Journal reported, “Mr. Amos Topping, of London, who is the successor of his father in the business of preparing microscope slides, favored us with a call at the Fisheries Exhibition, some time ago, and brought with him some of his preparations, which we were much pleased to see. All workers with the microscope are familiar with the preparations for which the elder Mr. Topping has long been famous. His son continues to supply the trade and microscopists generally with preparations of his own, many of which find their way to America”.

Lewis Wright wrote to The English Mechanic and World of Science in 1884, “May I be allowed one more word upon the subject of mounted insect preparations? As I recently contrasted unfavourably those now obtainable with some by the late Mr. Topping, it is, I think, only fair to say I have since received from the present Mr. A. Topping some of the best I ever saw. He tells me that, as I supposed, the demand is for a certain average quality at an average price”.

I have not found any advertisements for Amos Topping selling directly to the public. However, numerous retailers in Britain and the US advertised his slides (Figure 15), which is also evident from the large number of Topping’s slides that bear secondary labels (Figures 1, 5, 7, 10, 11, 12, and 13).

Amos Topping died unexpectedly on February 25, 1900.

Frederick W. Watson Baker wrote this obituary for Science-Gossip, “There is scarcely an amateur microscopist who is not acquainted with the name of Amos Topping, or who does not possess some of the objects prepared by him. The news of his death, which took place on February 25th, was received with deep regret. Although he was sixty-nine years old. he carried his age well, and had the heart and manners of a young man. His genial disposition, sympathetic nature, and even temper gained for him warm friends wherever he went. He may be said to have died in harness. It was his rule to call upon London opticians, with whom he did business, every week; and so recently as February 22nd, three days before his death, he paid his usual visits and seemed to be in his ordinary state of health. His death was due to syncope, and was quite sudden and unexpected.

His life had been entirely devoted to microscopical work. Mr. Topping's father enjoyed a high reputation in his day for his preparations for the microscope, and the son began to take part in the work at the early age of twelve years. For a period of fifty-seven years he has sent forth to the world objects of exquisite beauty, much above the average in their freedom from imperfection, and all characterised by great care and neat finish. In every department of his work he was extremely successful, but he has always been noted for one particular slide, and that is the proboscis of the blow-fly. No other preparer has succeeded in so mounting this subject as to render it sufficiently flat for use as a test-object; and unless some other worker knows the secret, it is likely to become one of the lost arts, and, as we at present know it, a rarity. Mr. Topping was always a little reticent regarding his method of preparing this object, and if he were asked whether he would mind saying how it was done, he promptly replied ‘With pleasure, sir’, and proceeded as follows: ‘I put a piece of sugar upon my bench and hold a blow-fly very closely to it; directly he puts out his proboscis to touch the sugar. I just snip off the tongue with a pair of scissors I keep handy for the purpose, and straightway mount it.’

With the death of Mr. Topping one of the links with the early days of practical microscopy is broken, and the whole microscopical world is the richer for his years of hard work and the poorer by his death. He leaves a widow, who was helpmeet, not only in his domestic life, but in his business labours, for forty-six years. He leaves also three daughters”.

“Group of diatoms”, by Amos Topping. Absence of wrapping papers suggests production after that style fell out of favor, ca. 1880-1900. Imaged with a 10x objective lens, transmitted light, and C-mounted digital SLR camera on a Leitz Ortholux II, four images stitched together with Photoshop.

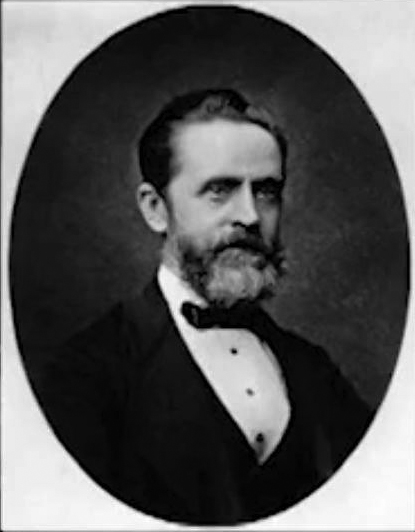

Figure 10.

“Grouped Polycystina”, by Amos Topping. Note retail by Watson & Son, London. William Watson’s business changed to that name ca. 1867, then became Watson & Sons in 1883. Imaged with a 3.5x objective lens, indirect light, and C-mounted digital SLR camera on a Leitz Ortholux II, two images stitched together with Photoshop.

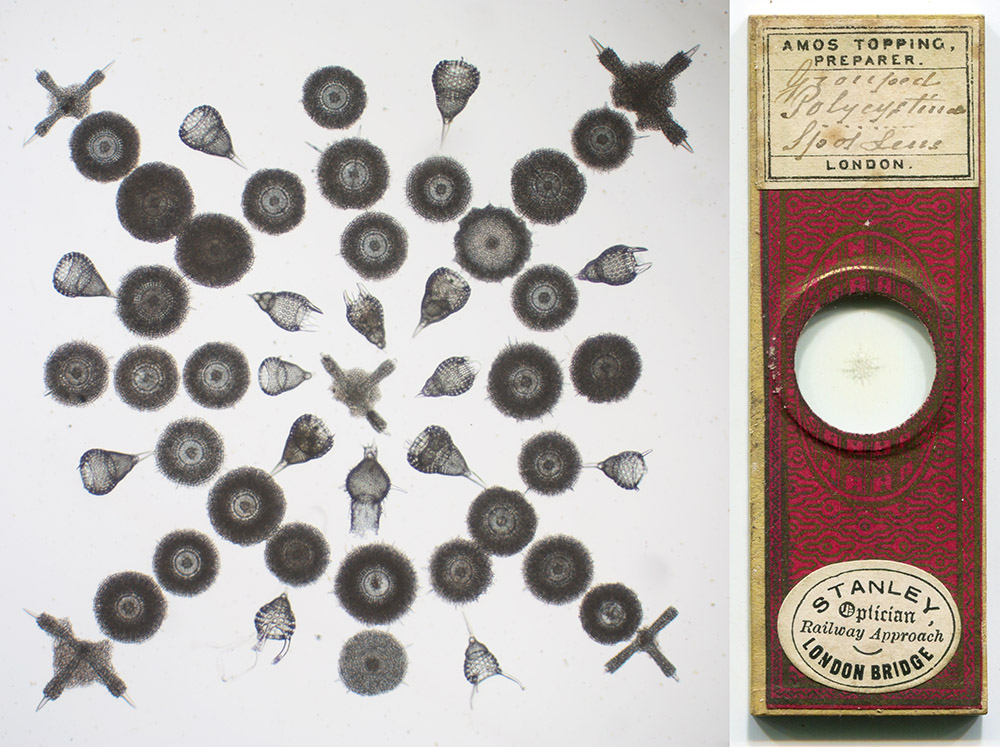

Figure 11.

“Grouped Polycystina”, by Amos Topping. Imaged with a 3.5x objective lens, indirect light, and C-mounted digital SLR camera on a Leitz Ortholux II.

Figure 12.

“Grouped Polycystina”, by Amos Topping. Imaged with a 3.5x objective lens, transmitted light, and C-mounted digital SLR camera on a Leitz Ortholux II.

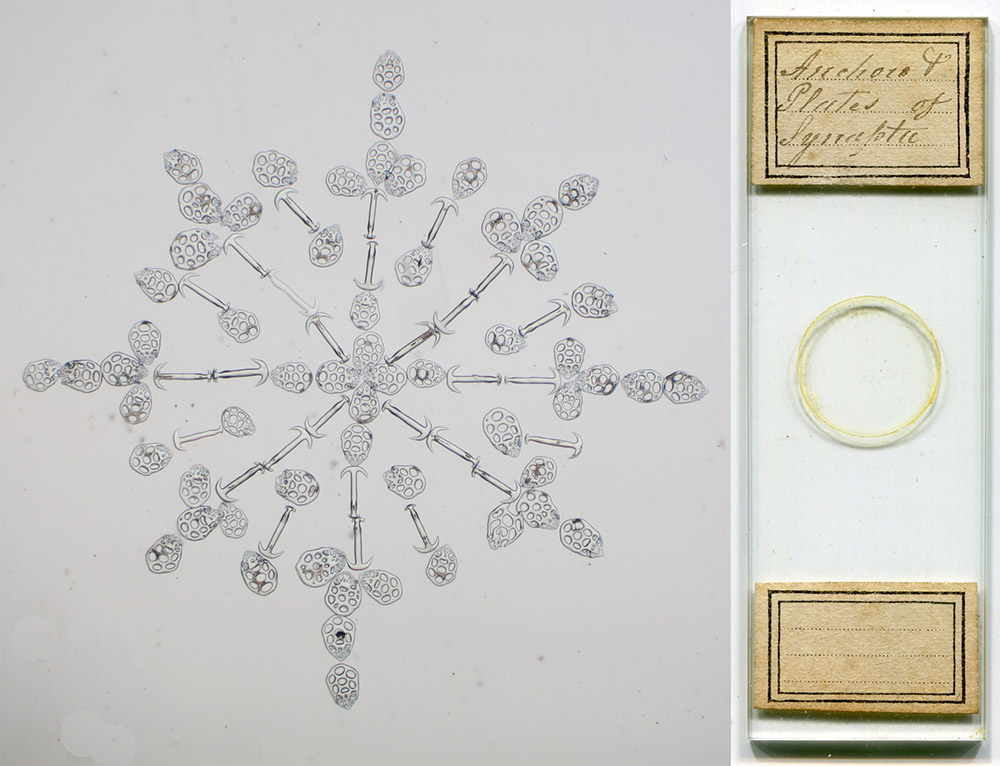

Figure 13.

“Scales of a Moth”, by Amos Topping. Imaged with a 3.5x objective lens, transmitted light, and C-mounted digital SLR camera on a Leitz Ortholux II.

Figure 14.

“Anchors & Plates of Synapta”, by Amos Topping. Imaged with a 3.5x objective lens, transmitted light, and C-mounted digital SLR camera on a Leitz Ortholux II.

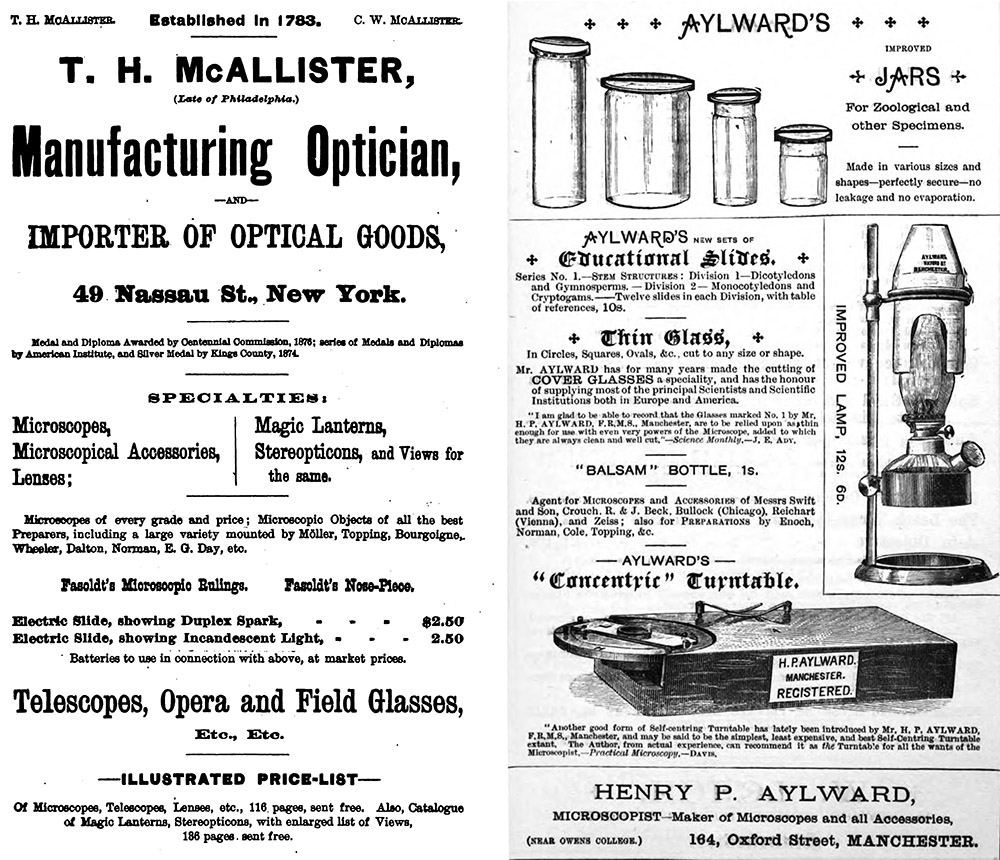

Figure 15.

Advertisements that include microscope slides by Amos Topping, from McAllister (1887, Philadelphia, USA), and Aylward (1888, Manchester, England).

Acknowledgement

Many thanks are due to the late Howard Lynk, for generously sharing slides and other information over the years.

Resources

The American Monthly Microscopical Journal (1883) Notes, Vol. 4, page 218

Annual Report of the Manchester Microscopical Society (1888) Advertisement from H.P. Aylward

Bracegirdle, Brian (1998) Microscopical Mounts and Mounters, Quekett Microscopical Club, London, pages 94 and 174, Plate 35-N, O, P, and Q

England census and other records, accessed through ancestry.com

Gill, Steve (2011) The two families of Charles Morgan Topping, Quekett Journal of Microscopy, Vol. 41, pages 553-555

Journal of the New-York Microscopical Society (1887) Advertisements from T.H. McAllister, multiple issues

Journal of the Quekett Microscopical Club (1871) Minutes of the June 23 meeting, page 243

Journal of the Quekett Microscopical Club (1872) Minutes of meetings, pages 28-30, 59-62, 118-120, and 121-125

Karop, G.C. (1900) Obituary notices, Journal of the Quekett Microscopical Club, page 440

The Monthly Microscopical Journal (1872) Minutes of the December 11 meeting

“Nun. Dor.” (1875) Preparing microscope slides, The English Mechanics and the World of Science, Vol. 22, pages 172-173

Stevenson, Brian, and Howard Lynk (accessed December, 2025) Charles Morgan Topping, 1799-1874, https://microscopist.net/ToppingCM.html

Watson Baker, Frederick W. (1900) Amos Topping, Science-Gossip, Vol. 6, page 344

Wright, Lewis (1884) Microscopic tests – mounted insect preparations, The English Mechanics and the World of Science, Vol. 39, page 34