John Boyd, 1852 – 1929

by Brian Stevenson

last updated June, 2018

John

Boyd was a relatively well-off Victorian-Edwardian industrialist and amateur

microscopist. He was an early member and officer of the Manchester

Microscopical Society, the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester,

and other microscopy clubs. He

also amassed what appears to have been a considerable library of microscope

slides. Some were probably of his own make, while others were acquired by

trading with other microscopists. Boyd’s collection included quite a few slides

that came from the personal collection of professional slide maker

Edward Ward, possibly after Ward’s death in 1901. Boyd and Ward were colleagues for many years in the Manchester Microscopical Society.

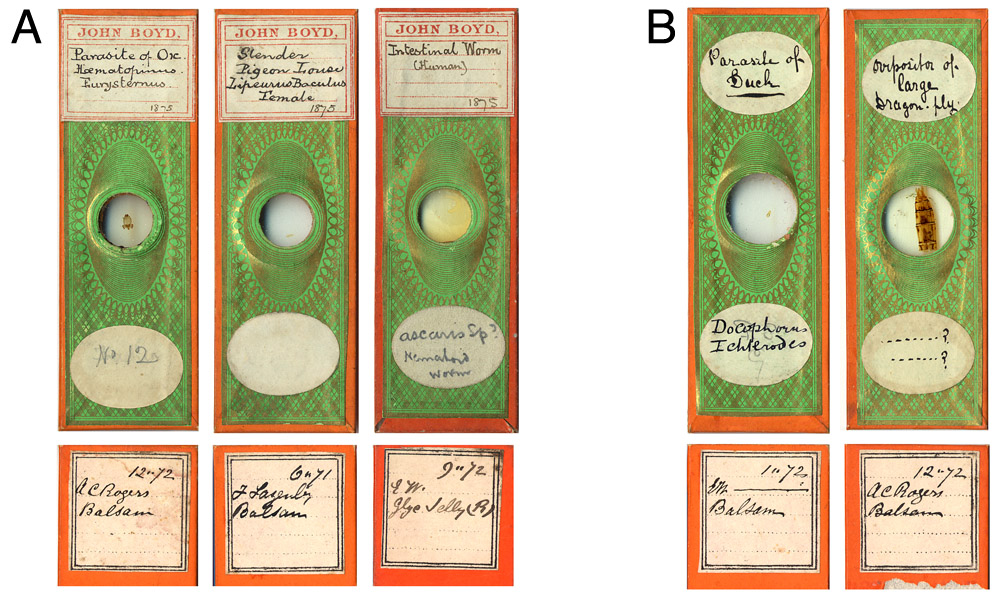

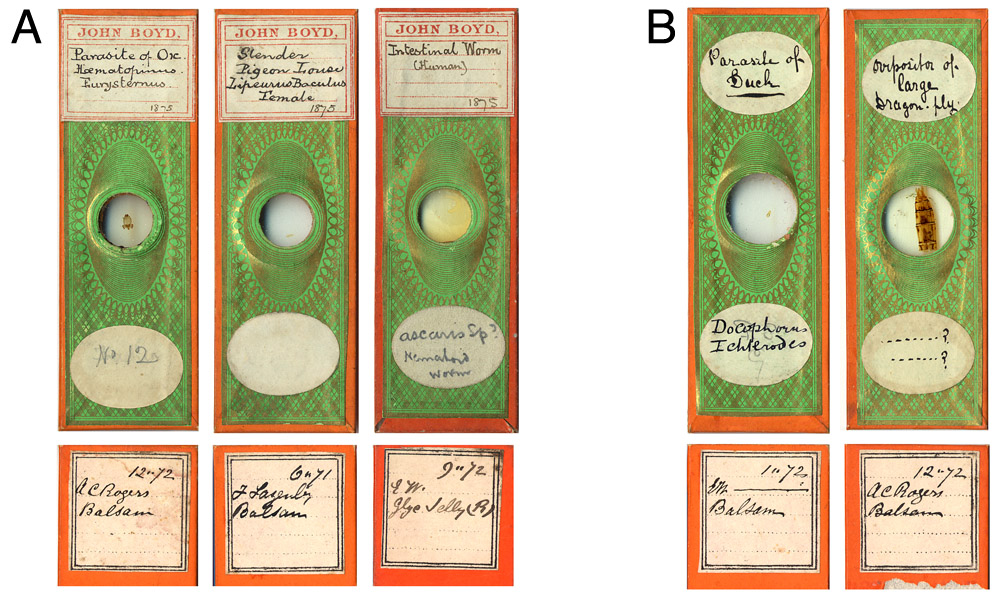

Figure 1. Several microscope slides that bear John Boyd’s

label. The wide variety of ringing styles and colors may be due to their

acquistion from other microscopists. However, the Manchester Microscopical

Society had frequent classes on slide making, so it is equally probable that

the variations stemmed from techniques learned over Boyd’s many decades as a

member of that Society.

Figure 2.

(A)

Examples of papered slides with John Boyd’s personalized label. The handwriting

on the square labels matches that on other Boyd-labeled slides (see Figure 1).

Many of these slides have additional labels or writing on the back, in a

different hand, listing names, dates and mounting media (snippets are shown

below each slide front).

(B) Such

labels, written in the same hand, are also often found on the reverse of slides

that do not have Boyd’s label, but instead have oval labels written in another

hand. Close examination of Boyd-labeled slides such as those in panel A

frequently reveals an oval paper label or traces of glue in an oval shape underneath Boyd’s label. Handwriting

comparisons indicate that the oval labels were written out by Edward Ward, and

suggest that Boyd acquired the slides in panel A from Ward’s collection.

John

Boyd was born in Manchester, England during the Autumn of 1852. He was the

third son of James and Isabella Boyd. James was originally from Scotland, but

by the time of John’s birth was a cotton yarn merchant in Manchester. Isabella,

and all of their children, were born in Lancashire. The 1861 and 1871 censuses

record the family as living in Chorlton upon Medlock, Lancashire. At the time

of the 1871 census, 18 year old John was recorded as being a salesman, possibly

for his father’s firm.

John

evidently had developed an interest in microscopy by his early twenties. In

1874, he advertised in Hardwicke’s

Science-Gossip for “Well-mounted

Diatomaceae, Zoophytes, Palates, Sections, Spicula, &c., for mounted

Parasites, showing all the legs.” His address was given as Victoria Park,

Manchester. It is notable that

Boyd was offering to provide slides of parasites, since fleas, lice, ticks and

the like were a passion of his, as evidenced by his frequent lectures on

parasites through the following years.

In 1875,

John Boyd was instrumental in the restoration of the “Leeuwenhoek Microscopical

Club” of Manchester. That club was founded in 1867, and consisted of only a

small number of members. From A Review of the Work of the Leeuwenhoek

Microscopical Club: “Throughout its

existence the Club has limited its membership to just that number which its

members could conveniently accommodate in each other’s house and seat around a

common table; but, generally, at the meetings there has been room for one or

two guests. There has never been a

period when it could not have enlarged its borders; but a doubling of the

number of its members would, in most cases, have proved inconvenient for

accomodation in a private house, and would, besides, have consumed too much

time in the examination of the suite of objects prepared to illustrate the

special study of the evening. It has been found by experience that six or eight

persons, with two or three microscopes revolving in order within the circle,

make the happy medium for the most effective consideration and discussion of

the many points which arise during the demonstration of any practical subject.” The club’s first President was the Reverend John E. Vize, who later achieved fame as a mycologist. The small number of

members led to the suspension of the club’s meetings in 1873, after several

members resigned due to business obligations, moving away, etc. On Sept. 30, 1875, the club reorganized

with a membership of five, including John Boyd. He was elected Secretary, and later served as President from

1890-91. Boyd was also noted in

the club archives as having developed a simple rotating table-top platform for

moving microscopes from one viewer to another. This club, and probably others

of which Boyd was a member, also contributed to his growing collection of microscope

slides. The Review notes that “at all

these meetings the exchange of slides illustrating the selected subjects of

study, or novel modes of mounting, was observed for many years…the cabinets of

the members were thus enriched with many valuable slides, which in some cases

remain as mementoes of friends passed away”.

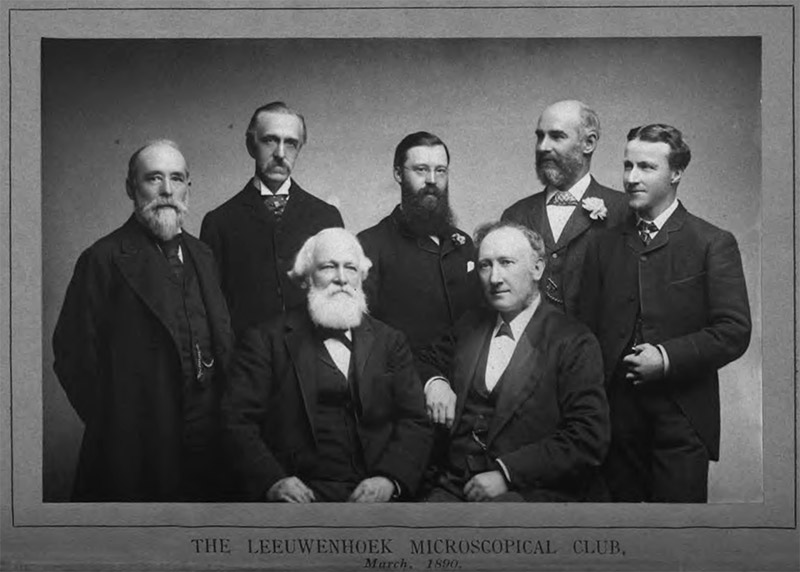

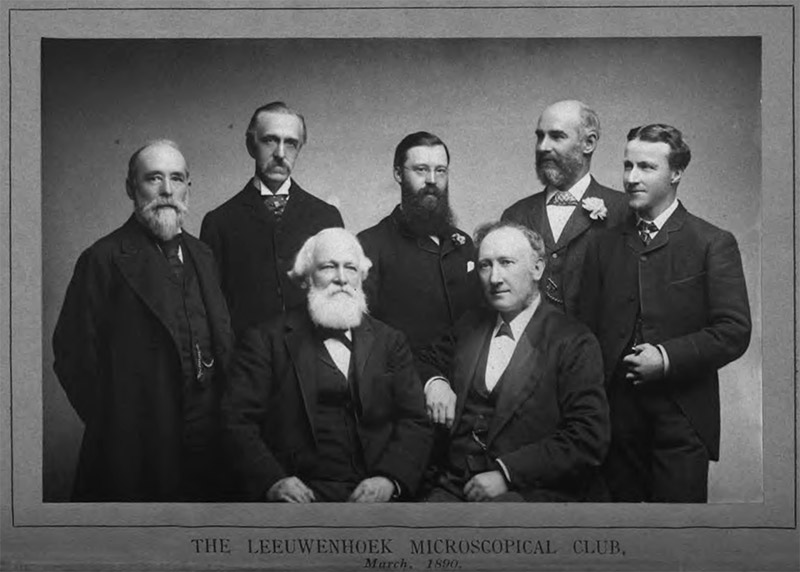

Figure 3. The Leeuwenhoek Microscopical Club, March 1890. The gentlemen can be identified from other photographs of them, and their ages at the time. Left to right, Mark Stirrup, William Blackburn, John Barrow, John Boyd (see Figure 5, below), John Tatham, Charles Bailey, and John B. Pettigrew. Slides with the labels of Charles Bailey, John Barrow and John Tatham are illustrated in Figure 4, below.

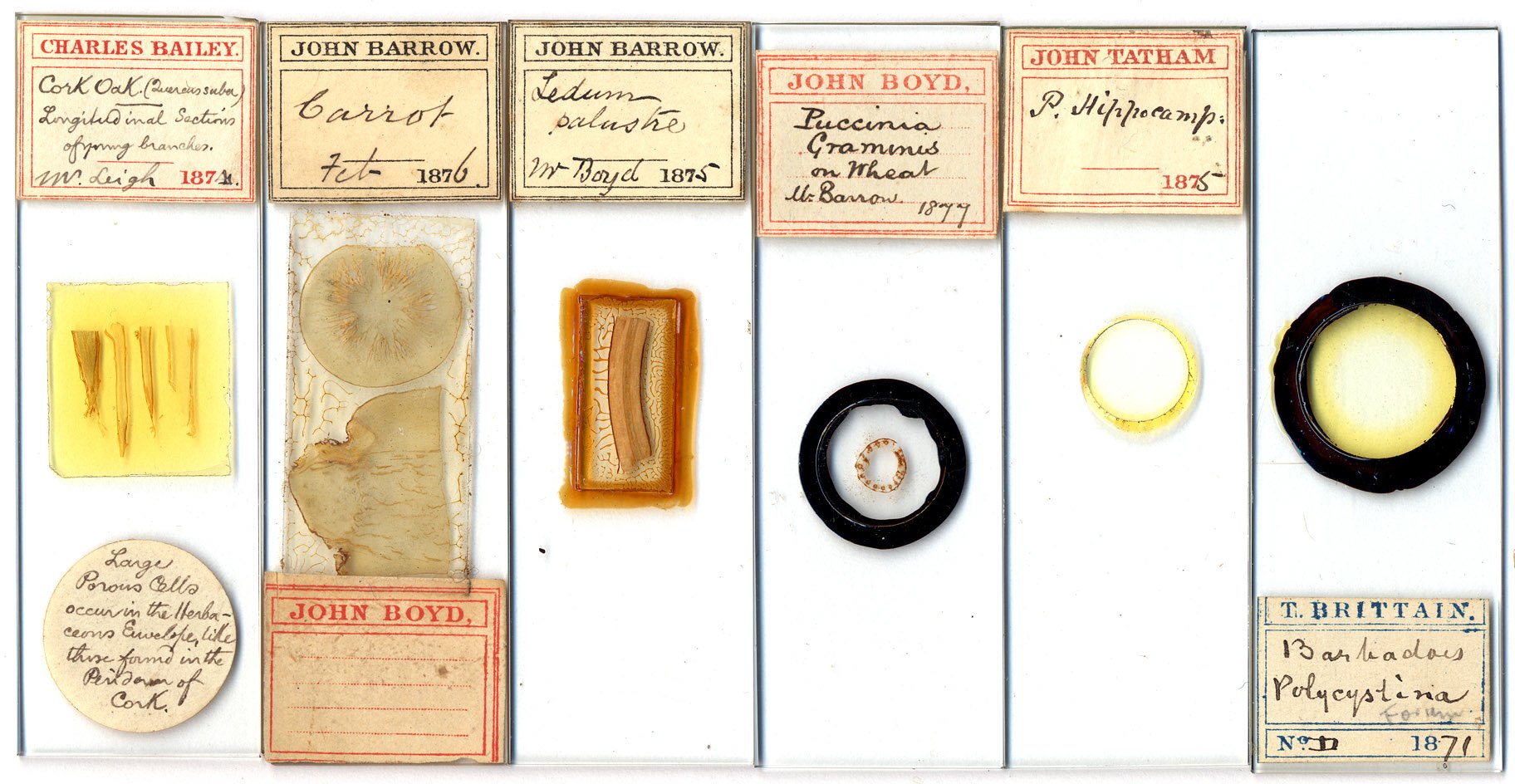

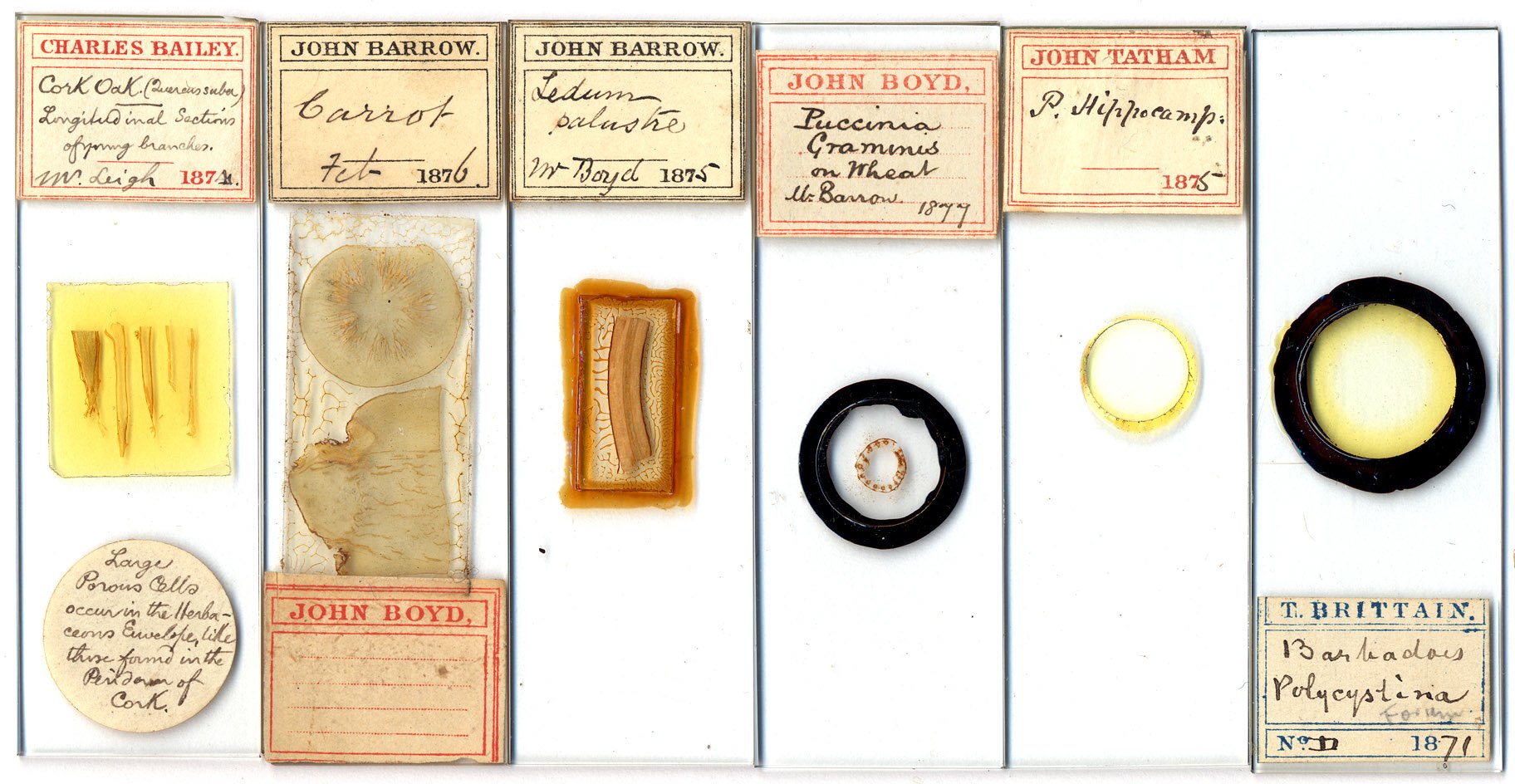

Figure 4. Examples of microscope slides once owned by John Boyd’s colleagues in the Leeuwenhoek Microscopical Club and the Manchester Microscopical Society. Left to right: Charles Bailey, sections of cork oak; John Barrow, sections of carrot, apparently given to John Boyd; John Barrow, section of Ledum, given to him by John Boyd; Puccinia fungus, with Boyd’s label, which was given to him by Barrow; John Tatham, diatoms; and Thomas Brittain, polycystina. It appears that all these colleagues used the same printer to make their labels.

Through

1875, Boyd continued to advertise for slides and specimens. Ads in Science-Gossip offered “Well-mounted Objects exchanged for Parasites

and their Eggs” and “Well-mounted

Slides or good Material for mounting; for unmounted Animal Parasites, in

spirits.” I have not located exchange ads from Boyd after 1875, even with

thorough searches of subsequent issues of Science-Gossip.

It may be that his clubs or established contacts provided Boyd with a

sufficient supply of new slides from then on.

In

1875, John Boyd was elected an Ordinary Member of the Literary and

Philosophical Society of Manchester. The following year he was elected a Member of the Society’s Microscopical

and Natural History Section. On Dec. 3, 1877, Boyd presented to the Section on

“the Chiego or ‘Jigger’ Flea (Pulex

penetrans, L.) from Demerara ”, and exhibited specimens of that

flea and of the human and cat fleas P. irritans and P. felis. The

following February, he exhibited slides of a fresh water sponge. In April,

1878, Boyd was elected a member of the Council of the Microscopical

and Natural History Section. His colleague from the Leeuwenhoek club, Charles

Bailey, was then Chairman of the Section.

The

small size of the Leeuwenhoek Microscopical Club’s membership led Thomas Brittain, who had been a frequent guest of that club, to form the Manchester

Microscopical Society in the year 1880. John Boyd was an original member, and

was elected as the club’s President in 1881.

Boyd

continued to present microscopical slides and lectures to his clubs, with a

bias toward blood-sucking arthropods. On March 15, 1880, he presented to the

Microscopical and Natural History Section “on

the Haustellum of the Haustellata, with diagrams, and also exhibited some

microscopical slides illustrative of the subject” (‘haustellata’ is an

artificial division of insects, including all those with a sucking

proboscis). On Nov. 18 of that

year, he exhibited to the Manchester Microscopical Society “some camera lucida drawings of Vaginicola

valvata; the long posterior-spine Daphnia Schaeferi, and also of Chydorus

sphaericus, all of which he had taken in Derwentwater.” On Feb. 3, 1881, he

exhibited and spoke on the “Ixodes (tick) of the Tortoise”, and on March 3 about “a

parasite from the skin of man, Demodex folliculorum; this was also illustrated

by a diagram prepared by Mr. Boyd.” At that year’s Manchester Microscopical

Society Annual Soiree, members exhibited “by

means of microscopes, which were placed on tables, arranged around the room, a

variety of objects illustrative of pond life, and other branches of the animal

and vegetable world, as well as preparations from the mineral kingdom. There

were present a large number of members and friends. During the evening the Rev.

J.G. Wood, M.A., delivered a lecture on Unappreciated Insects.” That night,

President Boyd exhibited a “live flea”,

“eggs of parasite of partridge” and “parasite of a fish (alive).” At the 1882

Soiree, Boyd exhibited “mange insect”,

“body louse”, “Daphnia pulex”, “Cyclops

quadricornis infested with Epistylis digitalis”, and “crab louse of man.”

A modern day collector of antique microscopes would love to have seen “the excellent display made by members, both

before and after the lecture. Over fifty microscopes had been set up, and under

each was shown some interesting object. The variety of stands was worthy of a

careful inspection. The best

English and Continental makers were well represented. The first-class stands of

Ross, Powell and Lealand, Smith and Beck, Swift, Crouch, and Zeiss; while

serviceable and good students’ stands were also shown by Messrs. Ward and

Aylward, of Manchester.”

One last story from Boyd’s long involvement in microscopy: on May 4, 1881, “Mr. John Boyd made a communication, in which

he stated that most Microscopists are familiar with the story that on a certain

old church-door some nails were shewn fastening what appeared to be fragments

of leather, and that tradition stated that the skin of a felon who had been

flayed had been nailed to the door. These portions of leather were examined

under the microscope, and were found to be really human skin, proving the correctness

of the tradition. Quite recently a circumstance came under my notice, in some

respects similar. That is to say, that a statement made as to a certain object

was proved to be correct from microscopical examination. I was visiting in a

country house in Scotland, and one day, to amuse a child who was playing about

in the room, a peculiar carved stool was brought out. It was of a very unusual

shape, narrow at the bottom, and broader and wider at the top ; and this top

instead of being flat was hollowed out. The material was the twin-trunk of a

small tree. It was said to have been brought by a missionary from Africa, and

although apparently a stool was really a pillow. As is well known to you, many

tribes dress their hair into most extravagant shapes. The process takes a very

long time, and the hair is not again dressed for a month or two. The small

stool is used to support the neck, to prevent the hair being dis-arranged. The

thought at once struck me that such a style of hair dressing would be particularly

conducive to the plentiful propagation of Pediculus capitis (author’s note: the

human head louse), and that I might by careful search find traces of these

interesting and beautiful creatures; and on further examination I discovered

dozens of the small white eggs of this parasite in recesses of the carving on

the little stool. When I announced this, there was quite a commotion, and the

question was asked if there was any danger of the eggs hatching. Evidently for

the moment, the fact of the many years which had elapsed since the stool was

brought from Africa was lost sight of. However, I was able to shew under the

microscope that the little lids which give such a pretty finish to the eggs of

this and of many other parasites were in each lifted off, shewing that the

little tenant had made his exit at some previous time. In mentioning this as another instance

of how microscopic examination, of an object which apparently was of little

interest to the microscopist, may confirm or confute statements made about it.

The missionary's tale about this peculiar little and apparently uncomfortable

stool, being used as a pillow, was abundantly confirmed by the presence of

these eggs.”

John Boyd

lived a long and apparently successful life. By the time of the 1881 census, he

was married to a Scot named Mary, with whom he had a one year old son named

James. They had two live-in domestic servants. John’s profession was “yarn merchant.” By 1991, they had moved

to Barton House, Didsbury, Lancashire, had three children, and John was a “cotton yarn agent.”

Boyd

served the Microscopical and Natural

History Section of the Literary and

Philosophical Society of Manchester in various offices through the 1890s

and into the 20th century. In 1921, Boyd donated 32 volumes of the Society’s Memoirs and Proceedings to that club. In

1923, he donated A Manual of the

Infusoria by W. Saville Kent (6 parts) to the Manchester Microscopical

Society, which appears still to be in their library. Boyd died in 1929, at the

age of 78.

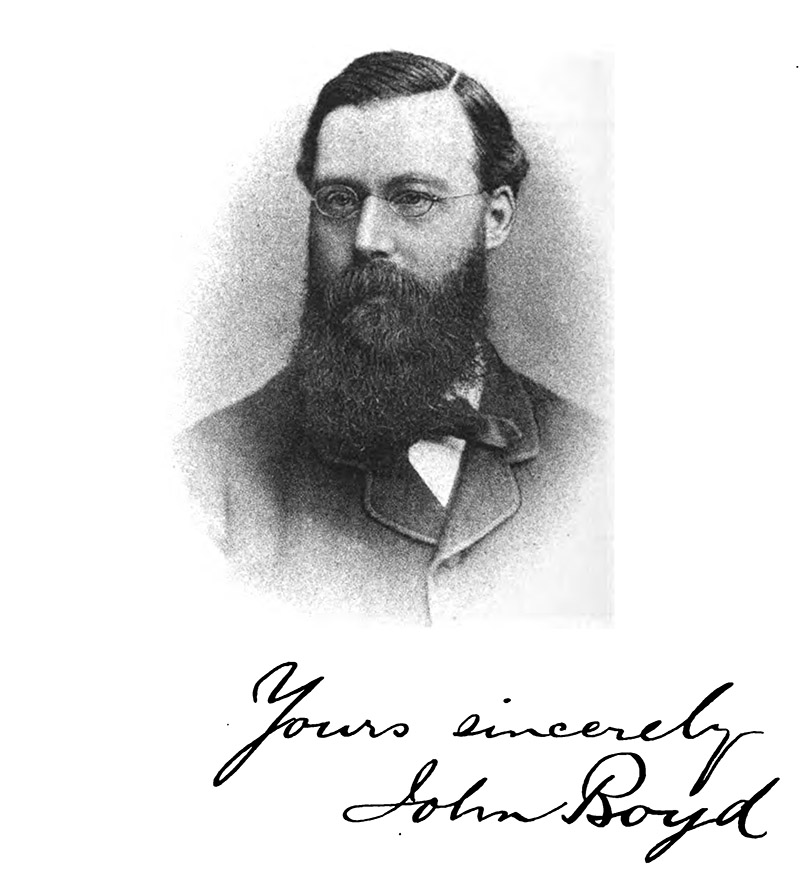

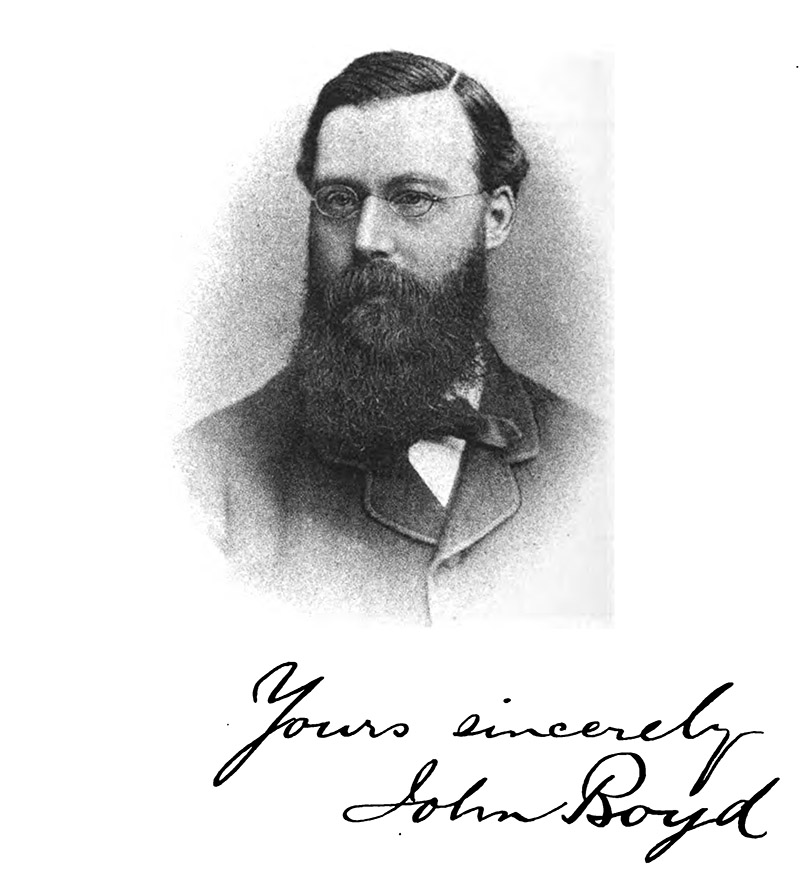

Figure 5. John Boyd, from the 1888 "Transactions and Annual Report of the Manchester Microscopical Society". Boyd was a long-standing member, and served as President in 1881.

Resources

Brian Bracegirdle (1998) Microscopical

Mounts and Mounters, Quekett Microscopical Club, London. pages 13 and 91,

and plates 5-O and 34-F

England census, birth, marriage and death records, accessed

through www.ancestry.co.uk

Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip (1874) Vol. 10, page 284

Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip (1875) Vol. 11, pages 24 and 283

Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip (1877) Vol. 13, page 210.

Manchester Microscopical & Natural History Society web

pages, on line at http://www.manchestermicroscopical.org.uk

Memoirs and Proceedings of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester (1888) Fourth series, Vol. 2, pages 9-10

Memoirs and Proceedings of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester (1891) Fourth series, Vol. 5, pages 60, 91 and 94

Memoirs and Proceedings of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester (1892) Fourth series, Vol. 5, pages 173 and 204

Memoirs and Proceedings of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester (1895) Fourth series, Vol. 9, pages 15-17 and 191

Memoirs and Proceedings of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester (1898) Vol. 42, pages xxvi, xxviii and lxviii

Memoirs and Proceedings of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester (1902) Vol. 46, pages xxxviii and xlvi

Memoirs and Proceedings of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester (1921) Vol. 54,

Memoirs and Proceedings of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester (1923)

The Northern Microscopist (1881) Vol. 1, January, pages 16, 63, 94-95,

and 116-119

The Northern Microscopist (1882) vol. 2, pages 73, 97-98, and 159-161

Proceedings of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester (1875-76) Vol. 15, pages 19 and 134

Proceedings of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester (1876-77) Vol. 16, page 90

Proceedings of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester (1877-78) Vol. 17, pages 104 and 228

Proceedings of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester (1878-79) Vol. 18, page 130

Proceedings of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester (1879-80) Vol. 19, page 155

Proceedings of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester (1883-84) Vol. 23, page 79

Proceedings of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester (1884-85) Vol. 24, page 49

A Review of the Work of the Leeuwenhoek Microscopical Club, Manchester, From October, 1867, to March, 1891. in

Pamphlets on

Protozoology (Kofoid Collection), Vol. 298, page 323, , on line at http://books.google.com/books?id=jmA0AAAAIAAJ