Carpenter

Carpenter and Westley

Philip Carpenter, 1776 - 1833

Mary Carpenter, 1787 - 1877

William Westley, 1807 - 1887

William Manning, 1834 - 1910

Eric Manning Stokes, 1855 - 1926

Ella Margaret Stokes, 1896 - 1998

by Brian Stevenson

last updated February, 2023

Beginning with a ca. 1800 optical glass grinding shop in Birmingham, England, Philip Carpenter built a major optical and scientific business in London. After Philp’s death, his sister, Mary Carpenter, took over the business. She and her business partner, William Westley, expanded the operation with a primary focus on projection lanterns and eyeglasses. The business passed to trusted employee (and possible relative) William Manning after William Westley’s death. After Manning’s death, a nephew of William Westley, then a great-niece, ran the firm Carpenter and Westley was sold out of the family in the 1940s.

From around the mid-1820 through the 1850s, Carpenter / Carpenter & Westley produced a substantial number of microscopes. Many of their products were acquired wholesale by other retailers, then resold under their other names. Evidently, large numbers of the “Carpenter’s Most Improved” microscope were manufactured (Figures 3 and 4), which are frequently seen nowadays with signatures by Carpenter / Carpenter & Westley and by other retailers, as well as without a signature. The firm also produced numerous small case-mounted microscopes (“Cary-Gould” types), which are also often seen with signatures by Carpenter / Carpenter & Westley or others (Figures 5-9).

Figure 1.

Microscope slides that were retailed by Carpenter and Westley. Prepared by professional slide-makers(left) Cornelius Poulton (1814-1854) and (right) John Barnett (1816-1882). Brian Bracegirdle’s “Microscopical Mounts and Mounters” shows additional Barnett slides that were retailed by Carpenter and Westley in plates 9-C and 44-H.

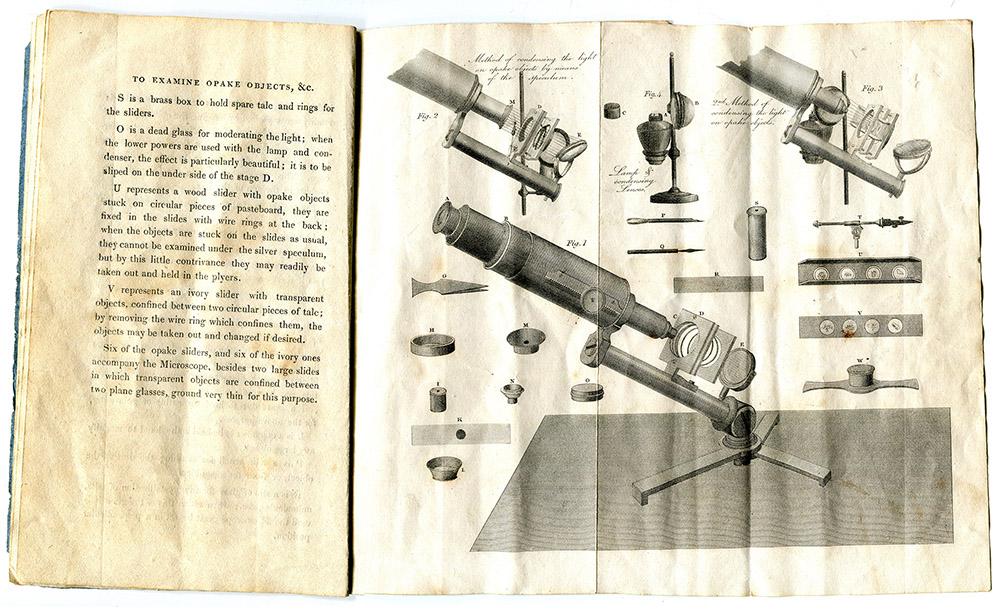

Figure 2.

Philip Carpenter’s “Improved Opake and Transparent” microscope, inscribed with his address of 24 Regent Street, London, ca. 1830. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://mhs.web.ox.ac.uk/collections-online#/item/hsm-catalogue-7018

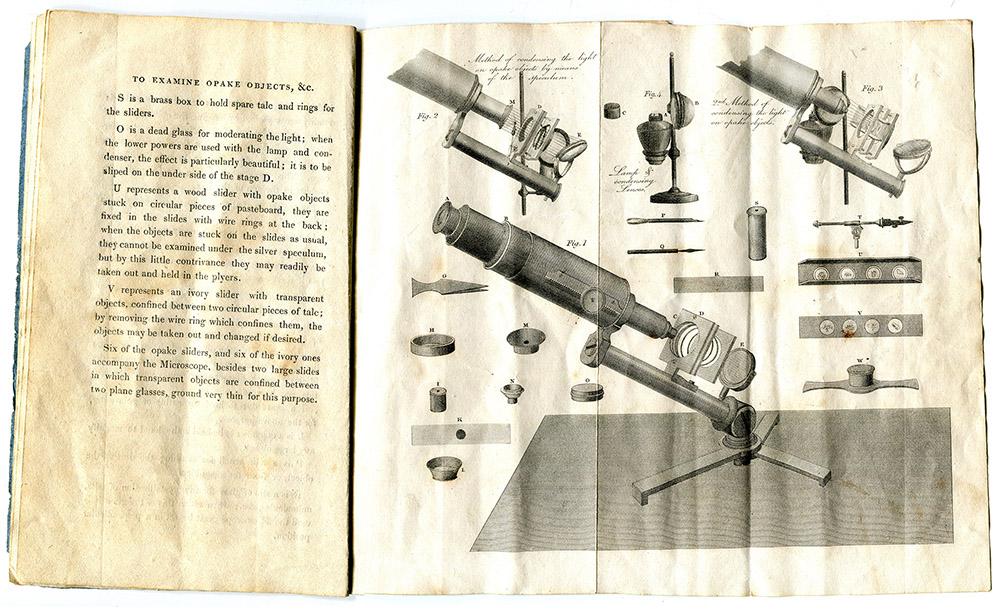

Figure 3.

Philip Carpenter’s “Most Improved Compound Microscope”, ca. 1830. This form was widely sold by the manufacturer or through wholesale retailers, and is frequently encountered with signatures from Carpenter, Carpenter & Westley, or other retailers, or without an engraved seller’s name. Images from the author’s collection or adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from internet auction sites.

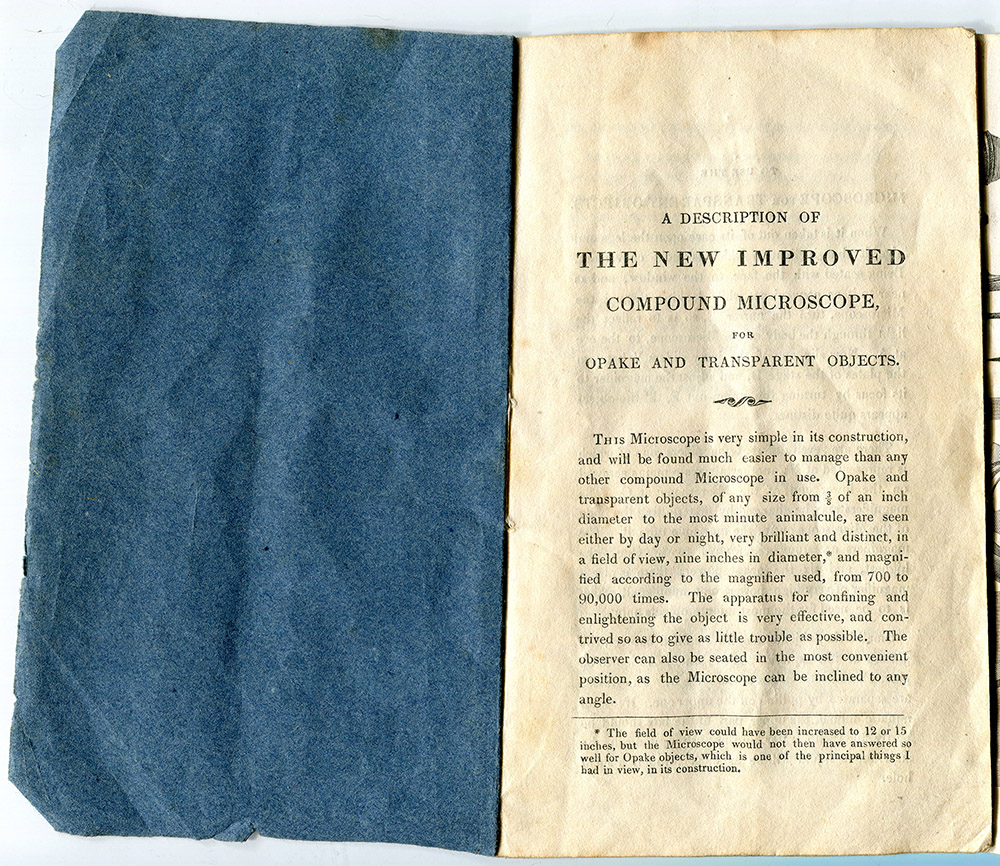

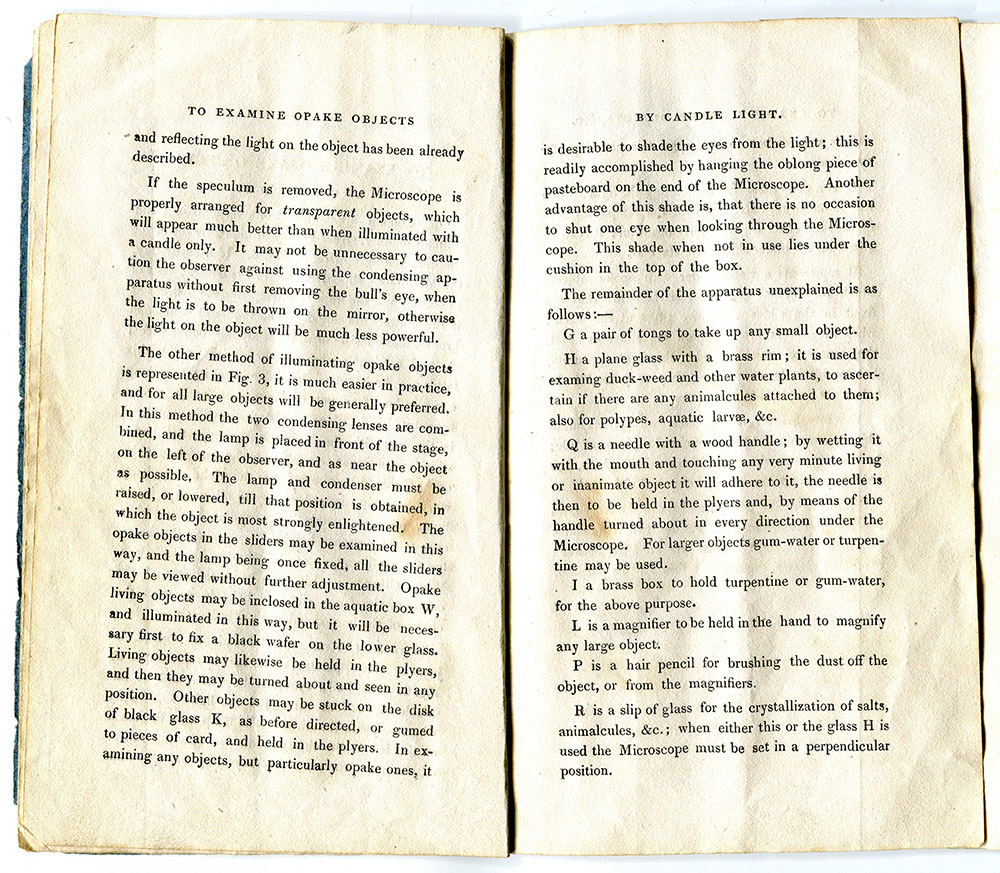

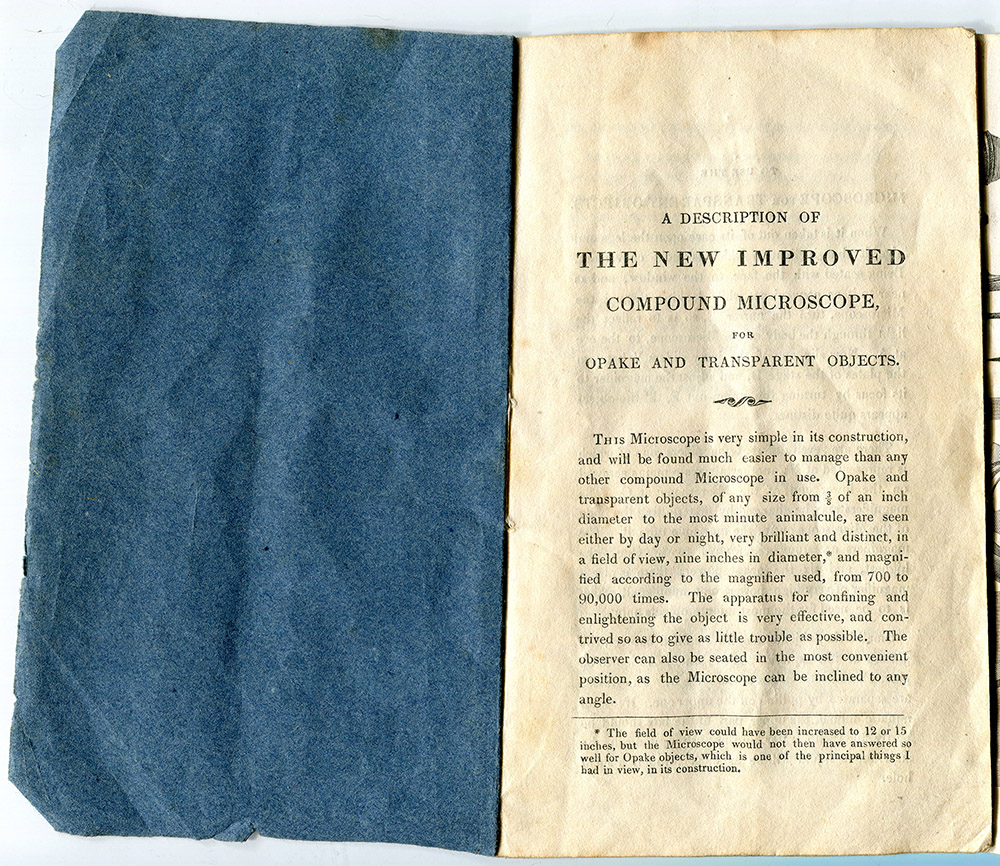

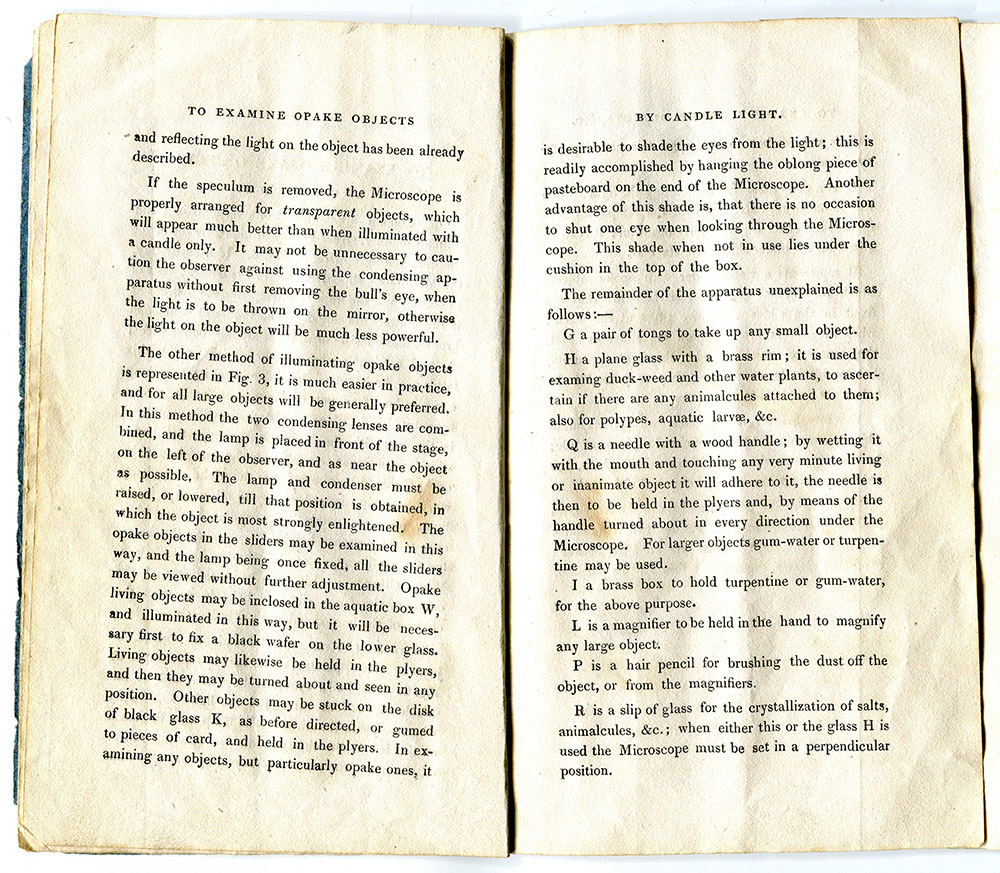

Figure 4.

Instruction booklet that accompanied Carpenter’s “Most Improved Compound Microscopes”.

Figure 5.

ca. 1830s case-mounted compound/simple (“Cary-Gould”) microscope, by Philip Carpenter. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an online auction site.

Figure 6.

Another style of ca. 1830s case-mounted compound/simple (“Cary-Gould”) microscope, with Philip Carpenter’s engraved name. Signed and unsigned versions are relatively common, due to Carpenter / Carpenter & Westley producing large numbers for wholesale trade. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from online auction sites.

Figure 7.

Carpenter & Westley case-mounted compound/simple (“Cary-Gould”) microscopes, ca. 1830s. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from online auction sites.

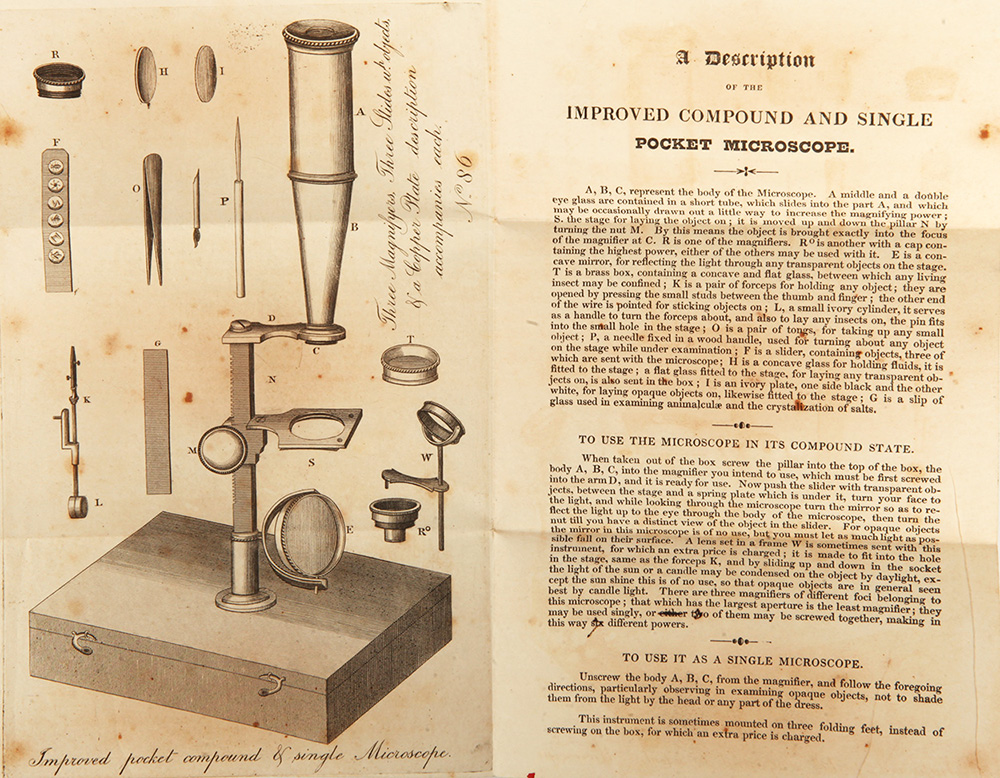

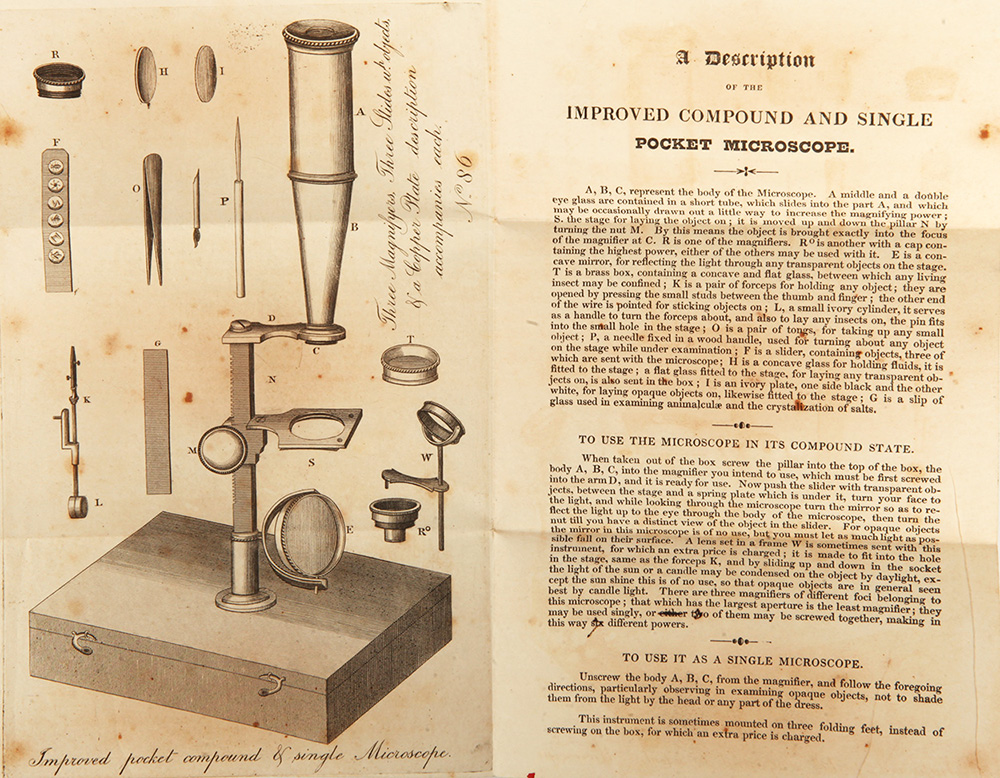

Figure 8.

Informational booklet that accompanied ca. 1830s Carpenter / Carpenter & Westley case-mounted compound/simple (“Cary-Gould”) microscopes. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an online auction site.

Figure 9.

ca. 1830s Carpenter & Westley compound/simple (“Cary-Gould”) microscope with a heavy, circular base. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://exhibits.charlotte.edu/s/Microscopes/item/2723.

Figure 10.

A less-common simple microscope by Philip Carpenter, ca. 1820s, Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co118608/botanic-microscope-of-unusual-design-in-case-by-philip-carpenter-botanic-microscopes.

Figure 11.

Philp Carpenter’s “Improved Compound Amician Microscope”, ca. 1830. Giovanni Battista Amici (1786-1863) developed a horizontal microscope that included magnifying mirrors in the late 1820s. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from http://nms.scran.ac.uk/database/record.php?usi=000-180-000-938-C .

Figure 12.

Compound microscope by Carpenter and Westley, ca. 1840. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co118856/compound-monocular-microscope-compound-monocular-microscopes .

Figure 13.

Compound microscope by Carpenter and Westley, ca. 1840. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an online auction site.

Figure 14.

Compound microscope by Carpenter and Westley, ca. 1840. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co118498/compound-monocular-microscope-by-carpenter-westl-compound-monocular-microscopes .

Philip Carpenter was born on November 18, 1776, in Kidderminster, Worcestershire. He was the first child of George and Mary (née Hooke), and was named after his paternal grandfather. Father George was a manufacturer / retailer of carpets. Five children followed Philip: Thomas Hooke Carpenter (ca. 1778 – 1843), who owned a wire-manufacturing business in Birmingham; Lant Carpenter (1780-1840), who was a well-known Unitarian minister, and father of microscopist/scientist William Benjamin Carpenter (1813-1885); Ann Carpenter Matthews (ca. 1781 - after 1833); Mary Carpenter (1887-1877), who remained single, and inherited Philip Carpenter’s optical business; and Sarah Carpenter (1789 - 1860), who also did not marry, and who live with Philip and Mary throughout her life. Philip’s will implied that Sarah was disabled, requesting funds “towards the maintenance and care of my poor sister Sarah”.

Father George’s carpet business declared bankruptcy in 1783. Litigation continued until at least 1789.

Philip and his family appear to have moved to the vicinity of Birmingham by 1800.

Philip Carpenter and one Thomas Ryland formed a partnership as “grinders of glass”, which was dissolved in 1803 (Figure 15). Presumably, the Carpenter-Ryland business manufactured eyeglasses and/or lenses for optical instruments. Ryland eventually become a manufacturer of metal products.

The next five years of Carpenter’s life are uncertain. However, Timmins (1866) reported that “About 1808, Mr. Philip Carpenter, the founder of the firm of Carpenter and Westley, commenced business in Birmingham in a more systematic manner than had been known before. Achromatic lenses had raised telescopes from mere toys to philosophical instruments, and Mr. Carpenter soon established a large trade, and supplied even Dollond himself with large numbers of telescopes bearing his famous name”. Timmins’ approximate date of 1808 could be consistent with Carpenter opening his own business after separating from Ryland in 1803. It is known that Carpenter operated a shop on Inge Street, Birmingham in 1808.

Around 1813, Carpenter moved to Bath Row. By 1819, he had an additional site at 111 New Street. He continued to use both of those locations through the 1830s.

David Brewster (1781-1868) developed and patented the kaleidoscope in 1817, which rapidly became a popular toy. Carpenter promptly negotiated a deal to be the only manufacturer of Brewster’s kaleidoscopes. Those early instruments state that Carpenter was the “sole producer” (Figure 16). Within a year, demand had exceeded Carpenter’ capacity, and Brewster arranged for several other manufacturers to produce kaleidoscopes (Figure 17). That year or two of monopoly proved to be very lucrative for Carpenter.

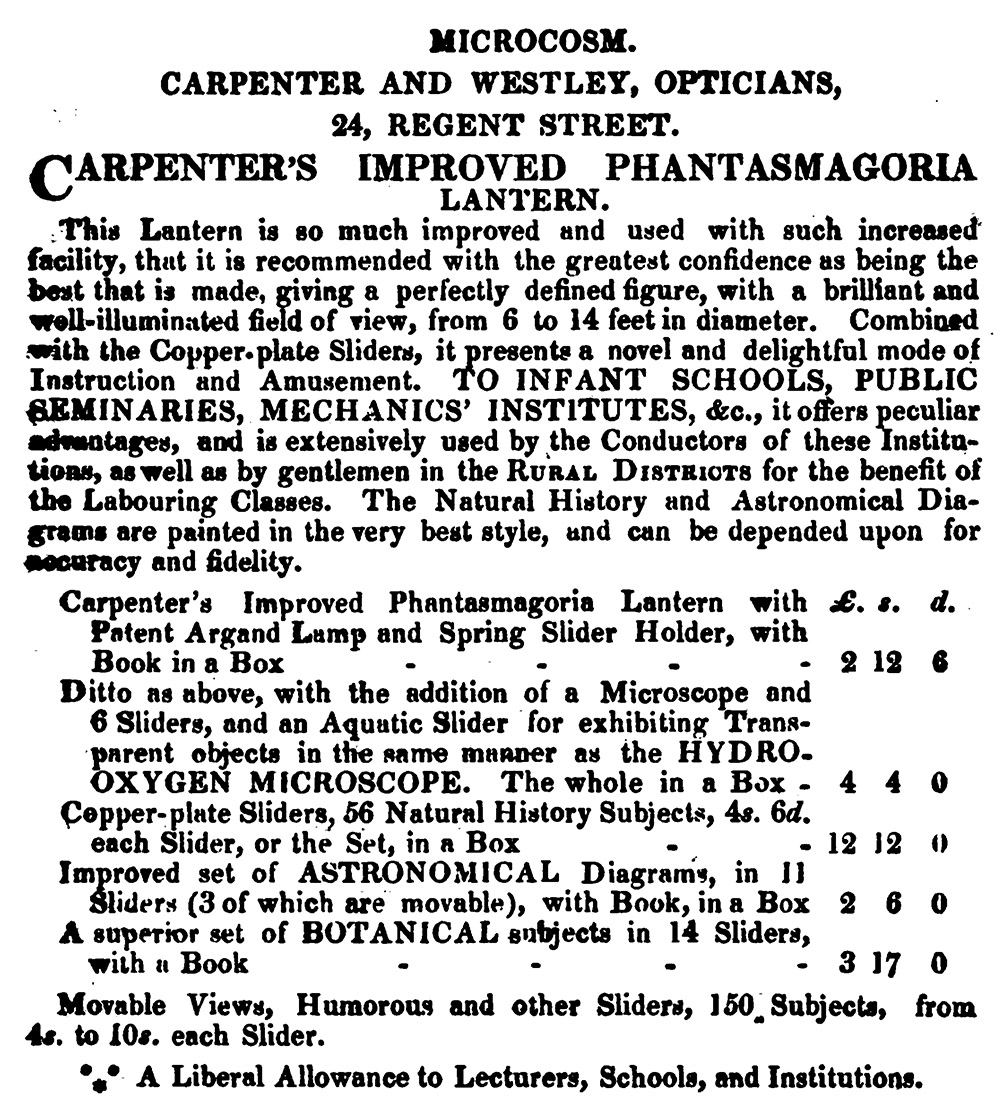

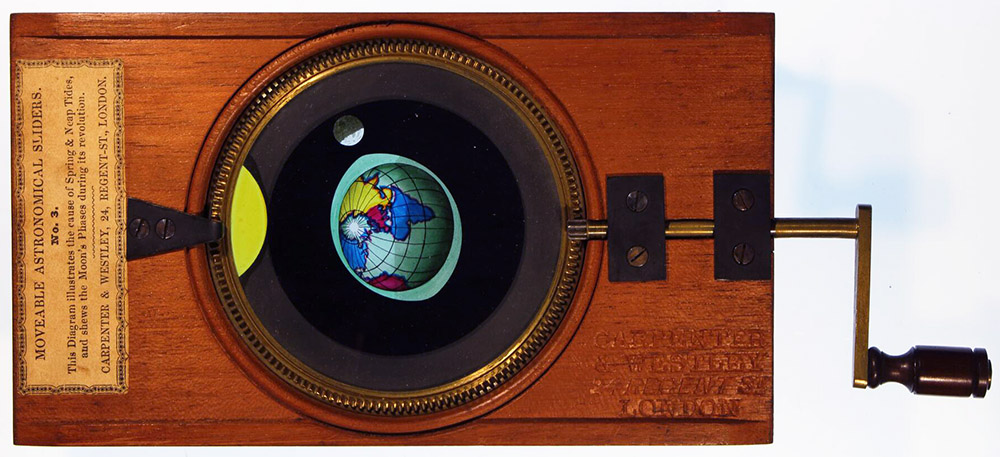

Around 1820, Carpenter developed his “Phantasmagoria” line of lantern projectors (Figures 18 and 19). He also produced large numbers of “copperplate” slides for the projectors. Their production involved stamping the outlines of images onto glass with engraved copper plates, which were then filled in with colored paints by skilled artists (Figures 20 and 21). Both were big commercial successes. They were sold directly by Carpenter, with his name attached, or wholesaled to other dealers who often sold those items under their own names.

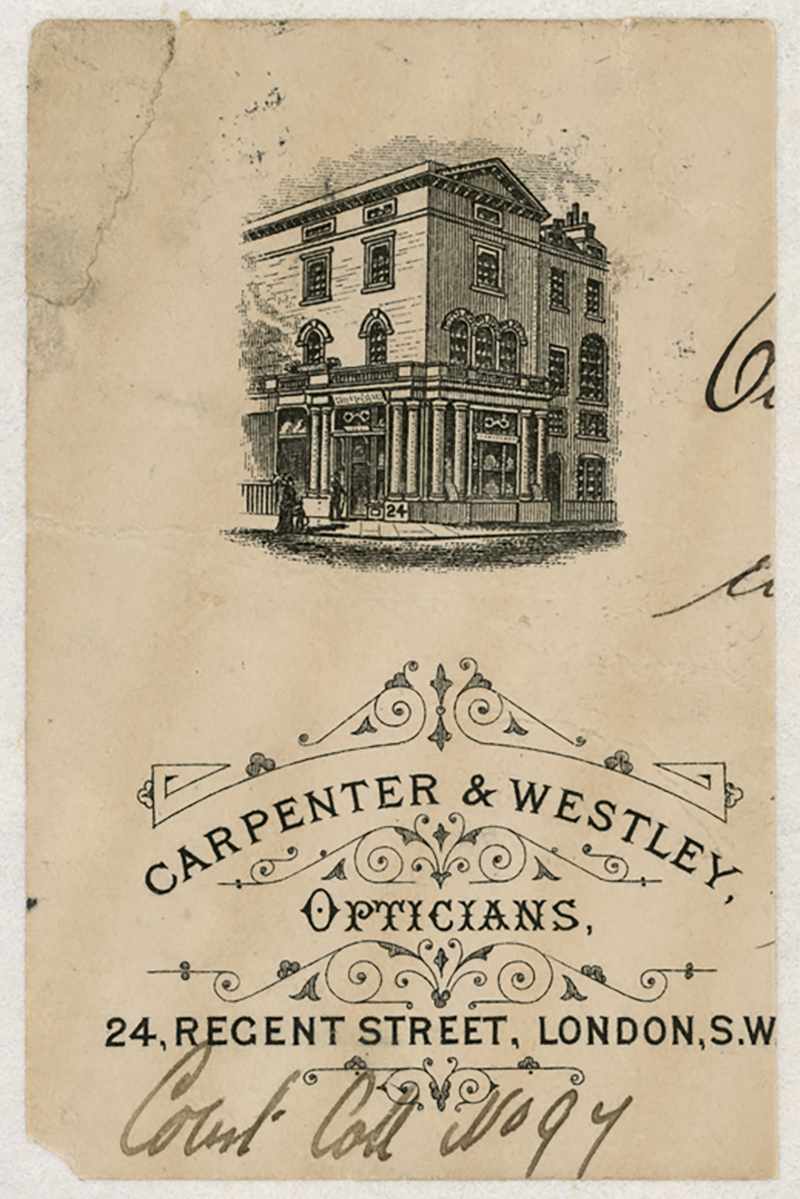

Carpenter’s success with magic lantern projectors led him to open his “Microcosm” shop in London during 1826 (Figures 22 and 23). He retained his Birmingham business for several years, which was eventually sold in 1837. The business at 24 Regent Street, London also served as the family home. Peter brought his unmarried sisters, Mary and Sarah, with him to London.

The “Microcosm” featured a large solar projection microscope, with which Carpenter put on daily exhibitions to the public (Figures 24 and 25).

Carpenter’s Companion to the Microcosm, published in 1827, provided insights on the man and his business. This advertisement inside states that Carpenter began optical work around 1797, and that eyeglasses were a major product, “Philip Carpenter Respectfully informs the Nobility, Gentry, and Public in general, that having been nearly thirty years engaged in business as a practical Optician, he is able to supply every article in the Optical way superior to most and inferior to none, P.C. wishes particularly to recommend his Spectacles and Eye-Glasses, as being the very best that can be made: his long experience and the great attention he pays in the selection of the best and most suitable Glasses and Pebbles, justify him in asserting that those Ladies and Gentlemen who honour him with their commands, will find the different imperfections of vision remedied by his Spectacles, in a very superior manner. Persons residing in the country may have their Eyes properly suited, by sending the Glasses they have been accustomed to wear, or if broken, any small piece of one. Those who have not begun to use Spectacles may have proper ones by informing P.C. whether they can read the small print of a Newspaper, and at what distance.”

Carpenter also provided insights on how he developed the Microscosm’s large projector, “Being engaged, some years ago, in a course of experiments; with a view to render the Compound Microscope better adapted for viewing opake objects, I soon perceived the great advantage of using lenses of large diameter, and increasing the length of the instrument. The expense of these large instruments, together with the disadvantage of the objects and mirrors being out of the reach of the observer, induced me to consider that, for general use, the length should be restricted by these circumstances, and I have accordingly, for some years been in the habit of making Microscopes upon these principles; a description of which will shortly appear in a publication on the Microscope, which is preparing for the press. Having been fortunate enough to procure some good glass, sufficient to make lenses of eight and nine inches in diameter, I was so much struck with the beautiful manner in which insects and other opake objects were exhibited, that I determined to try to what extent, in point of size, these instruments could be carried, and as the expense connected with these experiments was considerable, it occurred to me that if the instruments answered my expectations, an Exhibition of Microscopic Objects would prove a rational and instructive source of amusement to the public, and remunerate me for my time, and money expended. Accordingly the plate glass-houses (the only kind of glass suitable for the purpose being of that description) were applied to, but the Excise Law prevented the making of glass beyond a certain thickness, and it was only by chance, pieces could be procured of the diameter required, and of a sufficient substance. The houses in France and Germany were then applied to, and though they could furnish glass of any thickness and diameter, yet so few pieces could be obtained pure enough for the purpose, that nearly three years have passed before the requisite number could be worked. These difficulties being overcome, and the writer having fitted up the apparatus in an elegant and convenient manner, he looks forward, with confidence, to the support and patronage of the Public, and in particular to the Friends of Science and the Diffusion of Knowledge.”

Philip Carpenter played an indirect, yet important, role in popularizing the use of Canada balsam as a mountant, enabling microscopists to prepare long-lasting slides. James Bowerbank presented "Reminiscences of the Early Times of the Achromatic Microscope" to the Royal Microscopical Society on 11 May, 1870, and said about Canada balsam, “this valuable and effective mode of mounting microscopical objects, I am informed by Mr. Topping, was originally suggested by Mr. J.T. Cooper, an eminent analytical chemist, and was first applied to the preparation of large objects for exhibition by the solar microscope by a person of the name of Newth (sic), who was employed by the late Mr. Carpenter, the optician, of Regent Street, to exhibit them with the microscope, and who subsequently carried on a very profitable trade in objects so mounted.”

Philip Carpenter died on April 30, 1833, at the Regent Street home/shop.

Philip’s brothers, Lant and Thomas, were named as executors of his will. Philip requested that his property be sold to provide money for the support of sister Mary, with an expectation that Mary “will do what lies in her power towards the maintenance and care of my poor sister Sarah”. Lant and Thomas, who had their own businesses elsewhere, evidently decided to let Mary Carpenter instead operate the optical business. The name “P. Carpenter” remained on the London shop for several years.

Mary Carpenter was assisted by William Westley, who had been a key employee of Philip’s in both Birmingham and London. Mary Carpenter and William Westley were never married to each other, although descriptions of their business often mistakenly assume that they were.

The Birmingham branch became Carpenter and Westley ca. 1835 (Figure 26). William was born on March 27, 1807, in Birmingham, the eldest child of Isaac and Jane Westley. Father Isaac worked as a furniture japanner (1841 census) and clerk (1851 census). One of William Westley’s brothers, and several of his nephews, worked for Carpenter & Westley over the years.

The Birmingham shop was sold in 1837, to Robert Field (ca. 1787 - 1851). Field, Field & Son, and Field & Co. were major manufacturers of microscopes and other apparatus throughout the nineteenth century. They are best known today for their Society of Arts Prize microscopes.

The name of the London shop changed to Carpenter and Westley in 1837/1838 (Figure 27). Projection lanterns and their slides were major products. The Photographic News wrote in 1887, “When dissolving views were … first invented, William Westley put them before the public, but the method of their production was kept secret. William Westley raised lantern slide painting to a fine art; he selected the best artists and encouraged them to improve by paying them twice the usual fees for their work, with something in addition for any exceptional specimen of skill.”

William Westley was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Microscopical Society in 1840.

The 1851 census listed the inhabitants of 24 Regent Street as Mary Carpenter (“mistress optician”), Sarah Carpenter, William Westley (“optician master”), James Westley (William’s younger brother, “optician assistant”), Frederick J. Westley (William’s 15 year-old nephew, “optician apprentice”), three lodgers (a Member of Parliament/Magistrate, a Major General of the Army, and a Lieutenant Colonel of the Army), and two house servants.

Sarah Carpenter died on January 12, 1860.

At the time of the 1861 census, 24 Regent Street housed as Mary Carpenter (head of household, “optician”), William Westley (“co-partner” “optician”), William Manning and Frederick J. Westley (“optician assistants”), the Army General, and two housekeepers. Frederick left a few years afterward, and established his own optical business elsewhere in London.

“Optician assistant” William Manning had a relationship with the Westley family since his birth. He was born on December 9, 1834, son of Helen Manning, a “single woman”. All censuses except one report that he was born in Hampstead, Middlesex (London). William’s January, 1838, baptism record at St. Martin’s, Birmingham, states that he and mother Helen then lived on Powell Street, Birmingham. That was also where William Westley’s parents and siblings lived. At the time of the 1841 census, William Manning lived with the Westley family, but Helen Manning was not there. Manning was still living with the Westleys in 1851. As noted above, he lived and worked at 24 Regent Street in 1861. William Manning married Elizabeth Bevan on March 19, 1862, in Jersey. He became a Fellow of the Royal Microscopical Society in 1867. William and Elizabeth raised their family in Kensington, London, with all censuses recording his occupation as “optician”. We have not been able to locate any items or advertisements from William Manning, implying that he did not run a business in his own name. After William Westley died in 1887, Manning became owner. These facts suggest that William Manning was a manager of Carpenter and Westley, from the early 1860s onward. His birth in London, but life from at least three years old with the Westley family in Birmingham, then inheritance of Carpenter and Westley lead me to suspect that William Manning was not a mere foundling. Perhaps he was William Westley’s son?

The 1871 census recorded that 24 Regent Street was home to Mary Carpenter, William Westley, two more nephews of Westley (George and Westley Horton, sons of sister Hannah Westley Horton) who worked as optician’s assistants/apprentices, an Army colonel, and two servants.

Mary Carpenter died on October 30, 1877. An obituary: “Miss Mary Carpenter, whose death we recently announced, was born July 18th, 1787, at West Bromwich, where her parents, George and Mary Carpenter, then resided. After some years spent as a governess, she kept house for her eldest brother Philip, who was a manufacturing optician in Birmingham, and when, in 1826, he removed to 24, Regent street, London, Mary, with her youngest sister and their aged parents, accompanied him. On his death, in 1833, she was encouraged by her brother, Dr. L. Carpenter, to carry on the business with the help of Mr. Westley, who had for some time assisted in it, and whom, in 1837, she took into a partnership which continued for forty years. Her excellent judgment and equable temper, her perseverance and strength of character, combined with her accuracy and aptitude for accounts, will fitted her for the department she filled. She took an honourable pride in the character of her firm. ‘We not unfrequently’ (she wrote to a relative) ‘pay more to our workpeople than they demand, if unusual pains or time have been taken; from our customers we are constantly receiving letters testifying the confidence they repose in us; and we are quite free from what Dr. Hutton used to call the tricks of trade.' As her duties were congenial to her, she had no wish to relinquish them; and, at her partner's desire, she remained at her post nearly to the last. Old age enhanced the beauty of her character. In seasons of severe suffering, the self-control which had been her safeguard in active life preserved her sweet serenity. For the last year of her life she could not move without assistance, and she seldom left her room; but the plants which blossomed in it, the visits of children, the books and papers she read, the reports her friends gave of what was interesting them, and some business engagements, kept her mind cheerful and occupied. During the long period in which she was the sole survivor of her father's family, she more than ever took a motherly interest in her younger relatives and friends. As her attention was less needed for what had been her stated work, it was the more occupied in planning for their welfare. Her sympathy, her counsel, her help seemed always ready. The poor and suffering experienced her thoughtful kindness. She was not content to be a liberal contributor to public charities – ‘Her secret bounty largely flowed, And brought unasked relief’. Last July she commenced her ninety-first year, happy in the loving remembrance of the many to whom she was endeared. Her eye was not dim, nor her mind clouded, nor was the steadfastness of her affection and her faith impaired. Her only fear seemed to be of a long illness, which might exhaust the strength, though not the tender care of attendants. She was spared it; and peacefully entered into rest on the morning of Tuesday, October 30th. On the next Saturday a large number of those who loved and revered her, followed her remains to the Highgate Cemetery, where the Rev. J. Estlin Carpenter conducted the service; and the next day the Rev. P.H. Wicksteed paid a tribute to her memory, in the Little Portland-street Chapel. She and her sister had been among the first members of the congregation, which removed thither from York-street. Miss Carpenter left the following charitable bequests: Ministers' Benevolent Society, £200; Governesses' Benevolent Society, £200; London Domestic Mission, £100; Hospital for Consumptives, £100; Home for Incurables, £50; Portland-street Schools, £50; for benevolent objects in memory of her niece (Anna) Mrs. Herbert Thomas, £500; and to her partner, Mr. Westley, for the poor she aided, £200”.

A book on Remarkable Women wrote that Mary Carpenter was “a very able and excellent woman of business; one of those persons who do with their might whatever their hands find to do. The shop of Carpenter and Westley, opticians, in Regent Street, London, is well known; but few who pass it know that the Mary Carpenter whose life is sketched in the book before us was the partner who bore the name of Carpenter which appears above the door, and that she took an active part in the management for a great number of years. Under her skillful direction, the business grew large and profitable. She gave her whole mind to it, and tried to make everything perfect in its way, whether it related to the quality of the goods, the arrangements for the shop, or the comfort of those employed, continuing to give her assistance when she was of a great age. She lived a few months beyond her ninetieth birthday, having accumulated an ample fortune, and expended a large amount of it in deeds of thoughtful kindness and charity.”

After Mary Carpenter’s death, William Westley evidently ran the optical business as sole owner. The 1881 census listed him, two “optician’s assistants” nephews (George Horton and Eric Manning Stokes), younger brother John, two nieces, a cook, and a housemaid. As noted above, William Manning lived elsewhere, along with his wife, four children, an unmarried sister-in-law, a cook, a housemaid, and a nursemaid. Westley Horton, who had worked for Carpenter and Westley at the time of the 1871 census, was now a professional artist.

William Westley died on January 22, 1887, at 24 Regent Street. William Manning served as an executor of Westley’s will. An article in The Photographic News stated, “The oldest manufacturers of magic lanterns in this country are Messrs. Carpenter and Westley, of Regent Street, London. Philip Carpenter began the making of lanterns in Birmingham about the year 1808, and subsequently the late William Westley, who was born in 1807, entered his employment. In 1827, shortly after the removal of the business to London, William Westley rejoined his employer, first as foreman, then as partner; lastly he became the principal. He died at the beginning of this year, and was buried in Highgate Cemetery.” William Westley shares a grave monument with Mary Carpenter and other members of her family.

The writer of The Photographic News article further stated, “A few days ago I had the pleasure of meeting in the establishment a nephew of each of the founders of the firm, from whom the particulars herein given in relation to its history were obtained. They have about 12,000 slides on the premises, some of them by departed artists, whose productions they will not now part with on any terms, and all people connected with the lantern trade agree in telling me that photography has killed lantern slide painting as a fine art.”

William Manning took over operations of Carpenter and Westley, retaining the old name. Eyeglasses were the main product (Figures 33 and 34). Lanterns and their slides slipped to the side. Trevor Beattie (2013) wrote that he never located a Carpenter and Westley lantern slide made after 1887. Production of microscopes appears to have ceased in the mid-1800s.

The 1891 census listed William Manning and family at 21 Redcliffe, Kensington. His occupation was recorded as “optician” and “employer”.

Eric Manning Stokes, who had lived at 24 Regent Street in 1881 and then worked for William Westley as an “optician’s assistant”, was married and lived in Fulham, London by 1891. His occupation was listed as “optician” and “employed”. Stokes who was a son of William Westley’s sister, Jane Westley Stokes.

The 1901 census still listed William Manning as “optician” and “employer”, while Eric Manning Stokes was “optician’s manager” and “worker”.

William Manning appears to have died during late 1910. The March, 1911 census reported that his wife was a widow.

Eric M. Stokes reported himself to be an “optician’s manager” and “worker” on the 1911 census. Based on information from a descendant, Trevor Beattie (2013) reported that Eric Manning Stokes eventually inherited the Carpenter and Westley business. After Eric’s death, his daughter, Ella Margaret Stokes, took over the business. The 1939 survey of England, taken at the outbreak of World War 2, recorded that Ella Stokes worked in “ophthalmic dispensing". She was unmarried, and lived in Holborn with her widowed mother. Carpenter and Westley was sold “to a major chain of opticians in 1940” (Beattie, 2013).

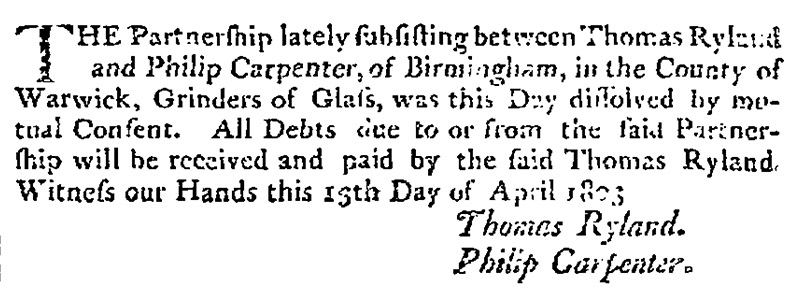

Figure 15.

1803 record of the dissolution of the glass grinding partnership between Philip Carpenter and Thomas Ryland. From the “London Gazette”. Carpenter wrote in 1827 that he had been in the optical business for “nearly thirty years”, implying that Carpenter worked with the Ryland and Carpenter business, or another like it, since around 1797.

Figure 16.

A ca. 1817 kaleidoscope that was manufactured by Philip Carpenter. He was the sole maker from 1817 until around 1819. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from http://journal.sciencemuseum.ac.uk/browse/issue-07/philip-carpenter-and-the-convergence-of-science/the-kaleidoscope/

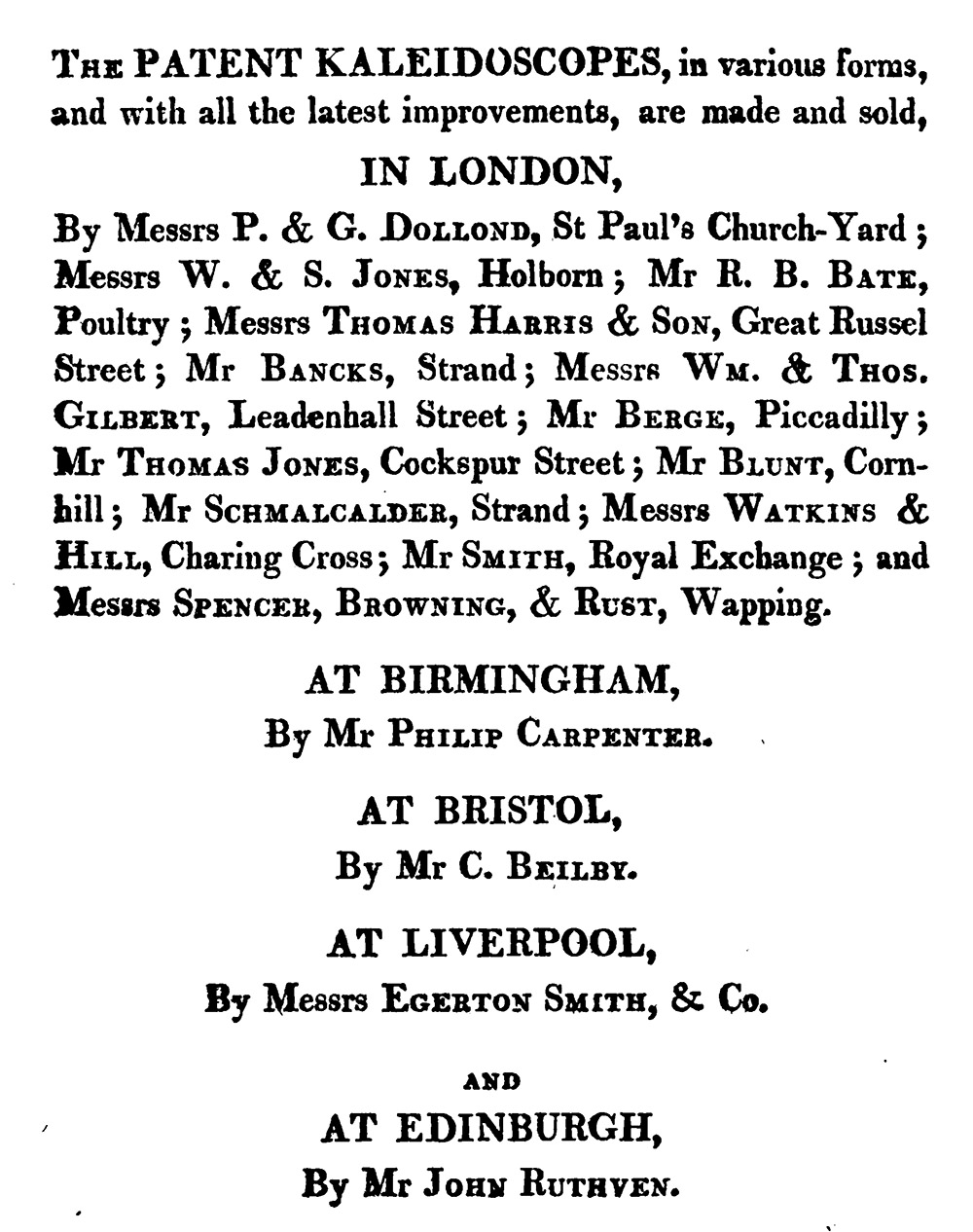

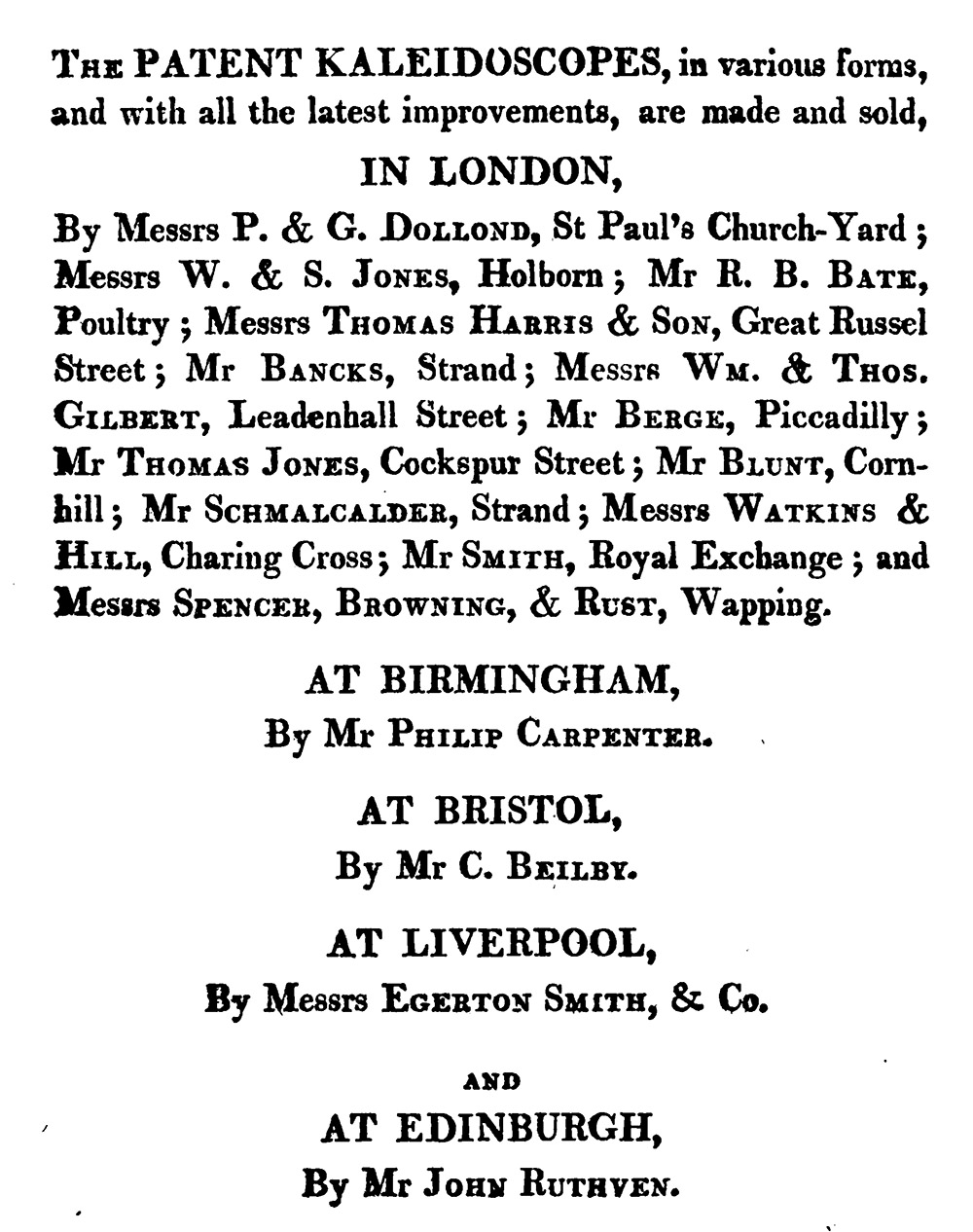

Figure 17.

List of kaleidoscope manufacturers/retailers in 1819, from David Brewster’s “A Treatise on the Kaleidoscope”.

Figure 18.

“Phantasmagoria” lanterns by Philip Carpenter (left and center) and by Carpenter & Westley (right). Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from http://journal.sciencemuseum.ac.uk/browse/issue-07/philip-carpenter-and-the-convergence-of-science/the-improved-phantasmagoria-lantern/ or from internet auction sites.

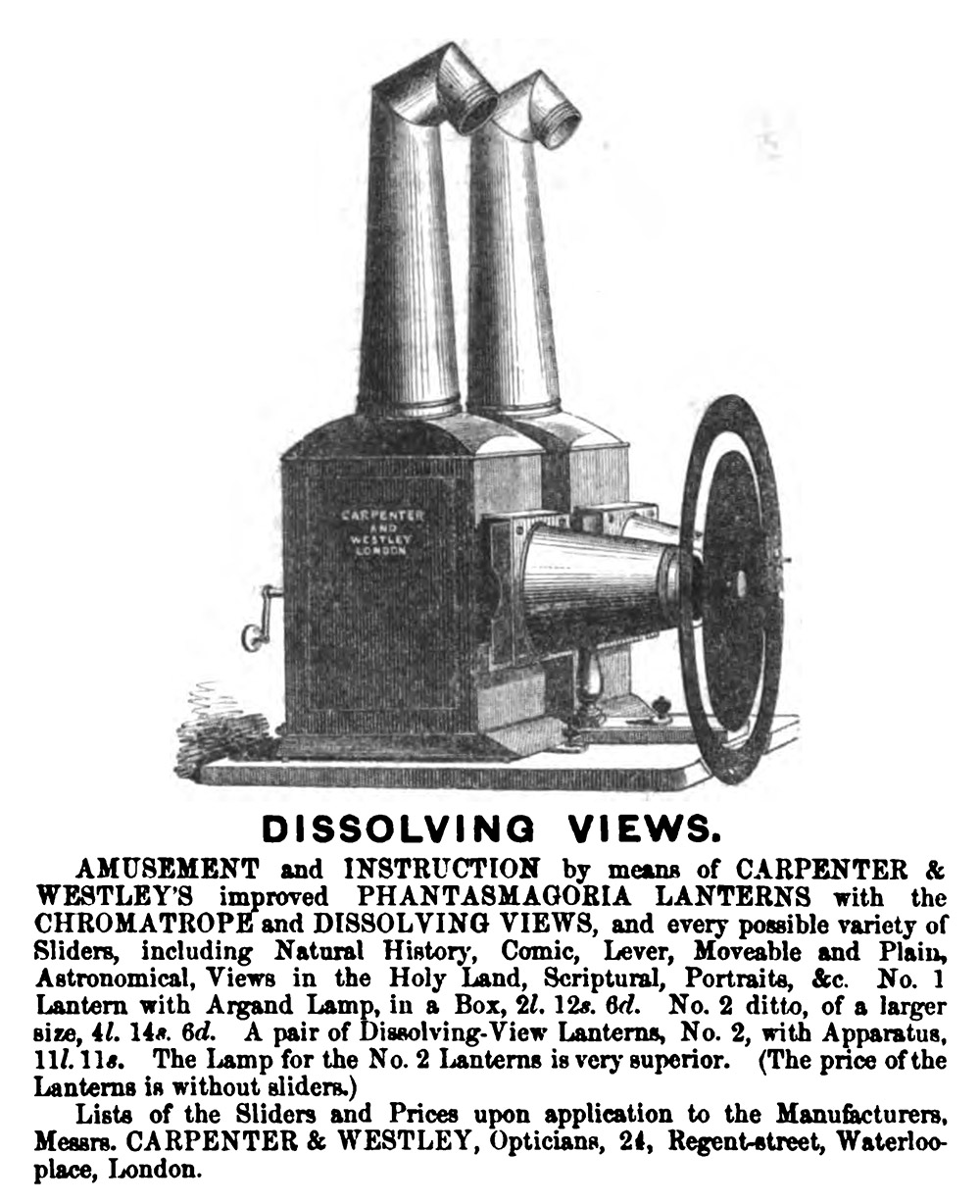

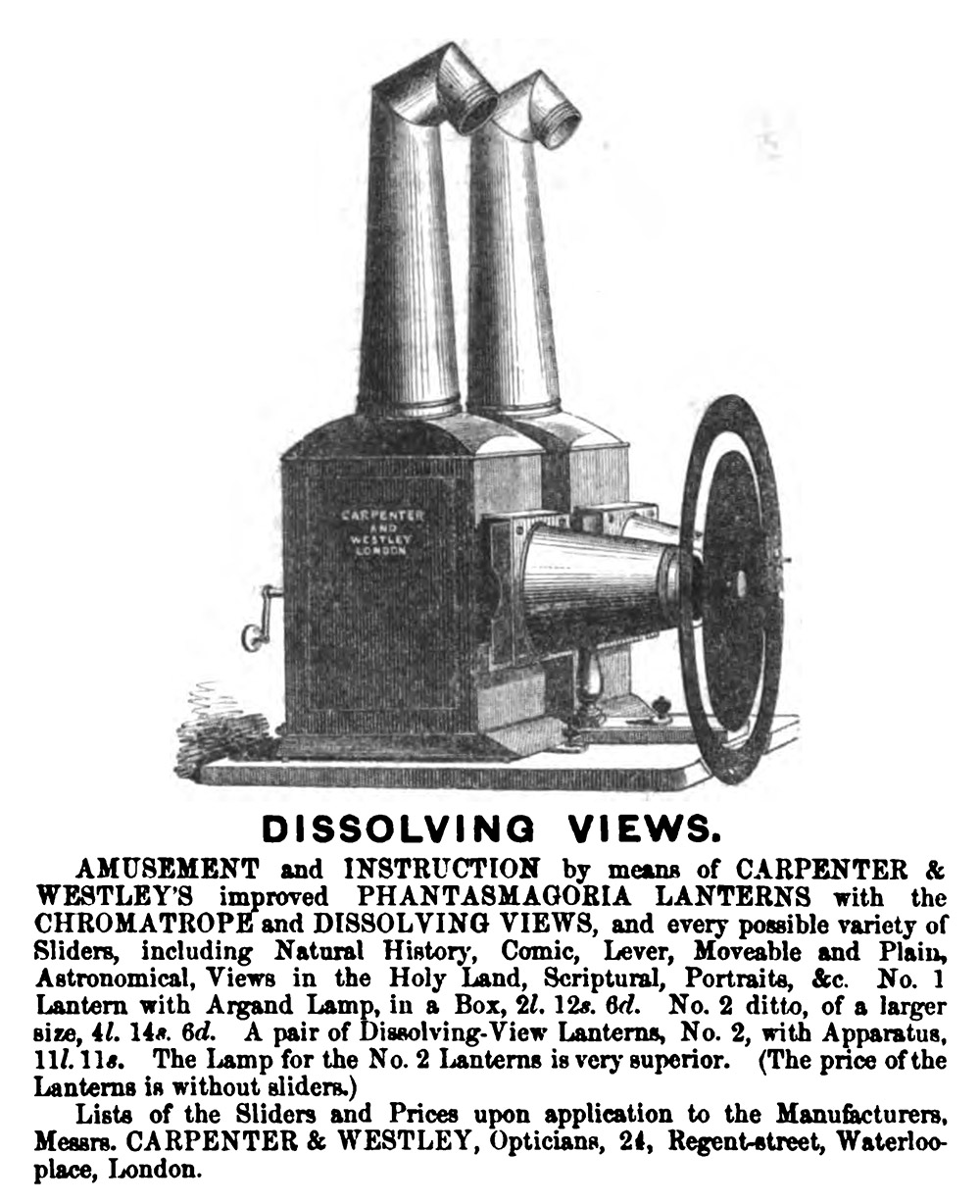

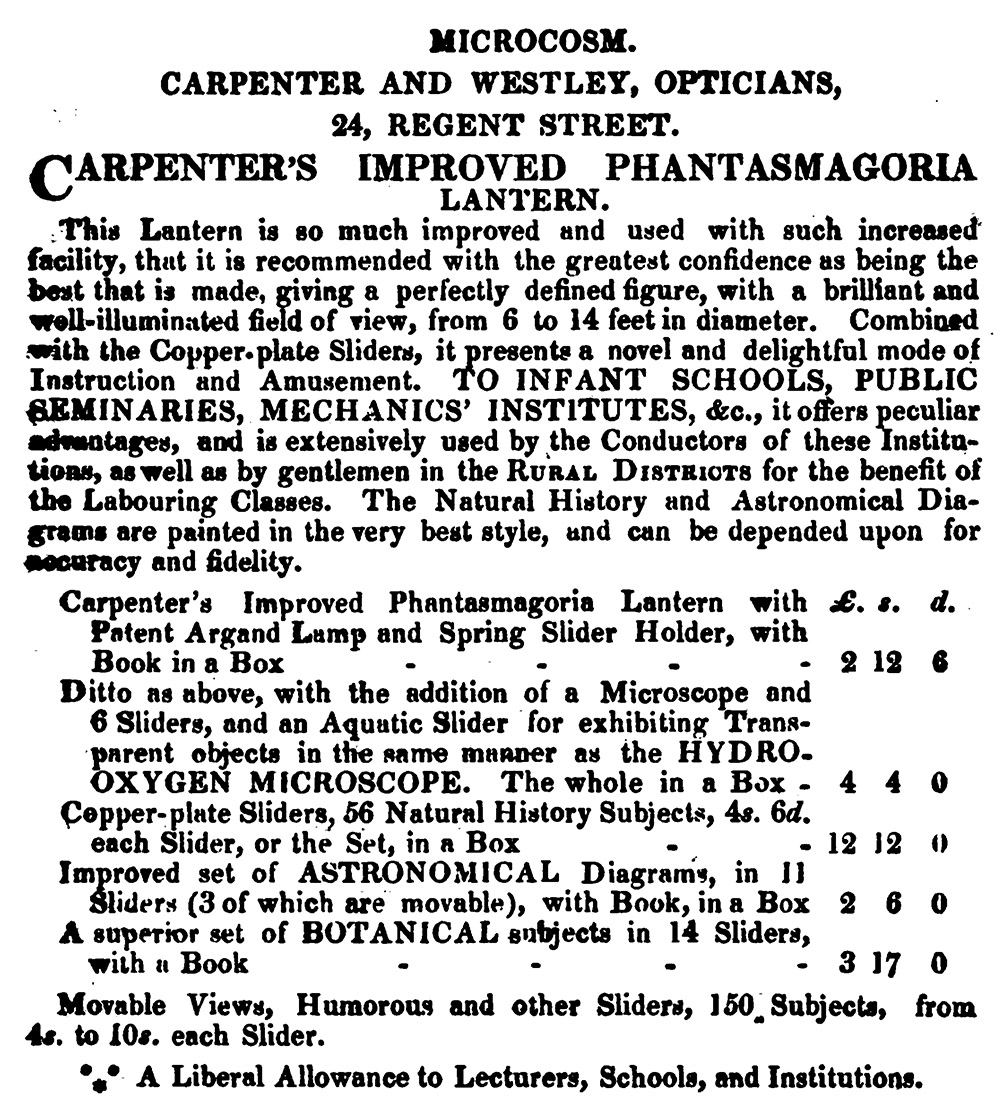

Figure 19.

An 1852 advertisement for Carpenter & Westley Phantasmagoria lanterns with a “dissolving view” attachment. The revolving disc on the front has two slits that each progress from narrow to full width of the projector lens. One can thus display a single image from one projector, then slowly rotate the disc to narrow then eliminate that projected image while simultaneously expanding an image from the second projector. This facilitates smooth presentation of slideshows, as opposed to use of a single projector (which creates visual and time gaps when the projectionist changes slides) or use of paired lanterns where one would need to move a screen from the front of one projector to the other. Blending image transitions is more pleasing to audiences than abrupt changes. “The Photographic News”, in 1887, wrote, “Messrs. Carpenter and Westley introduced the crescent form of dissolver, in which a crescent was cut out near the circumference of a circular disc; it gets rid of the shadows on the picture cast by opaque dissolvers”. Advertisement from John Quekett’s “A Practical Treatise on the Use of the Microscope”, third edition.

Figure 20.

A ca. 1820-1830 “Copperplate” lantern slide that was manufactured by Philip Carpenter. Mammalia slide number 13, it shows kangaroo rats, two types of moles, and a porcupine and hedgehog. The colors were applied by painting the backs of the glass discs. Although the slide is not signed, the stamped “Copperplate Sliders” indicates this as a Carpenter production. The slide measures just under 14 x 4 inches (36 x 10 cm), with circular glass discs of 2 ¼ (5.5 cm) in diameter.

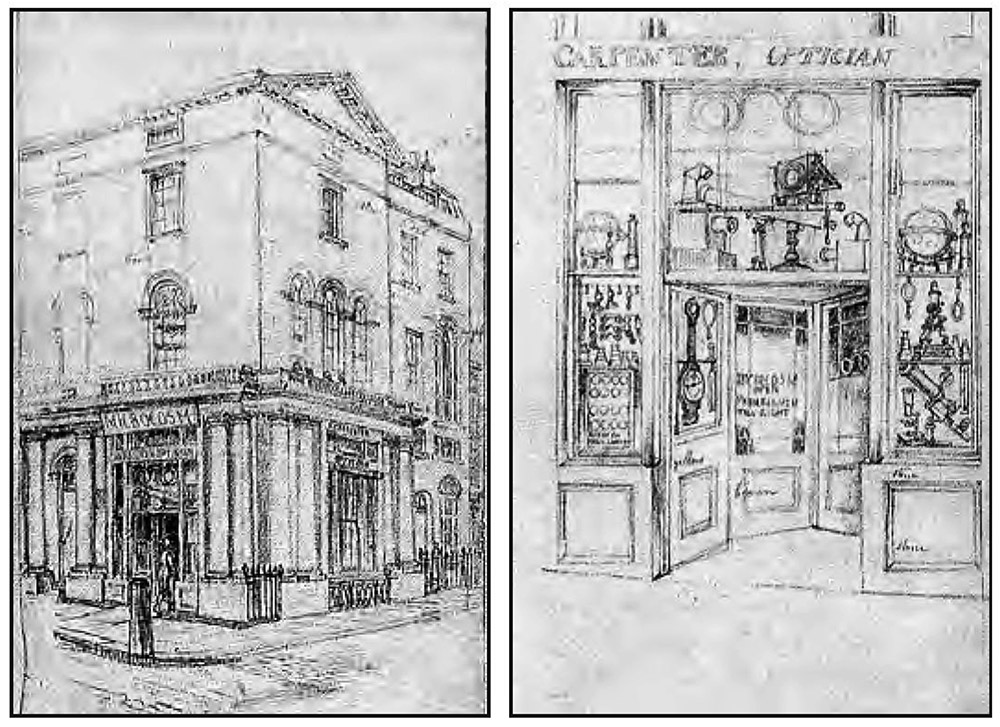

Figure 21.

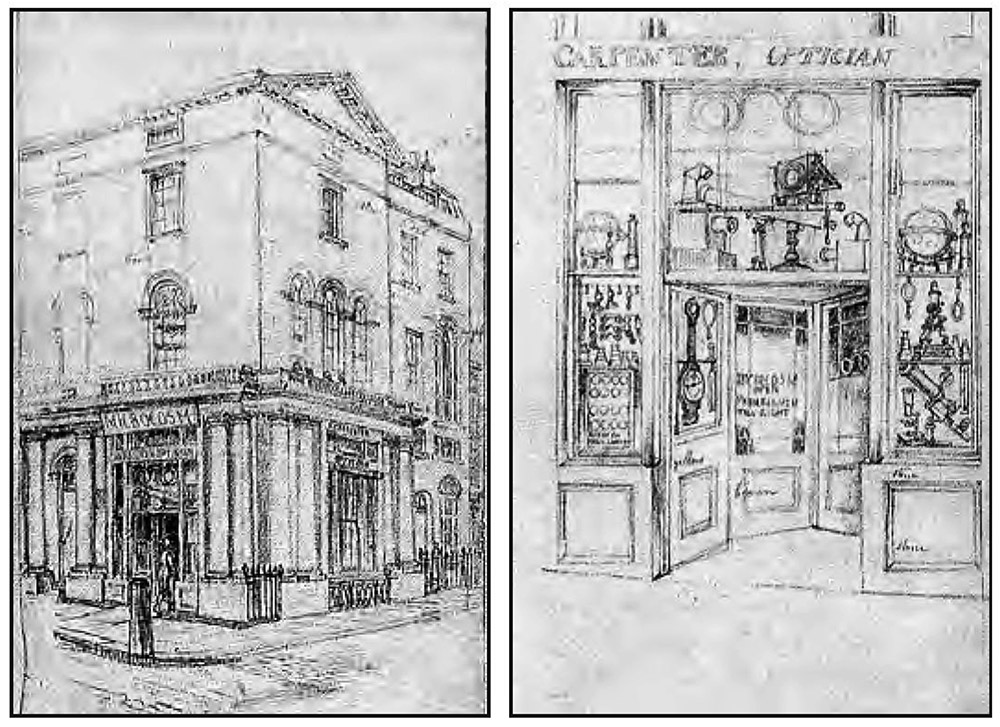

Philip Carpenter’s shop at 24 Regent Street, London, from drawings by George Sharf, 1828. Examples of items manufactured and/or sold by Carpenter can be seen in the picture on the right. Note the Culpeper-type microscope on the middle shelf to the right of the door. Two other microscopes are shown on the shelf below: a Jones’ Most Improved-type and a case-mounted “Cary-Gould”-type. A Phantasmagoria lantern is perched above the door. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from Talbot, 2007, and from the British Museum.

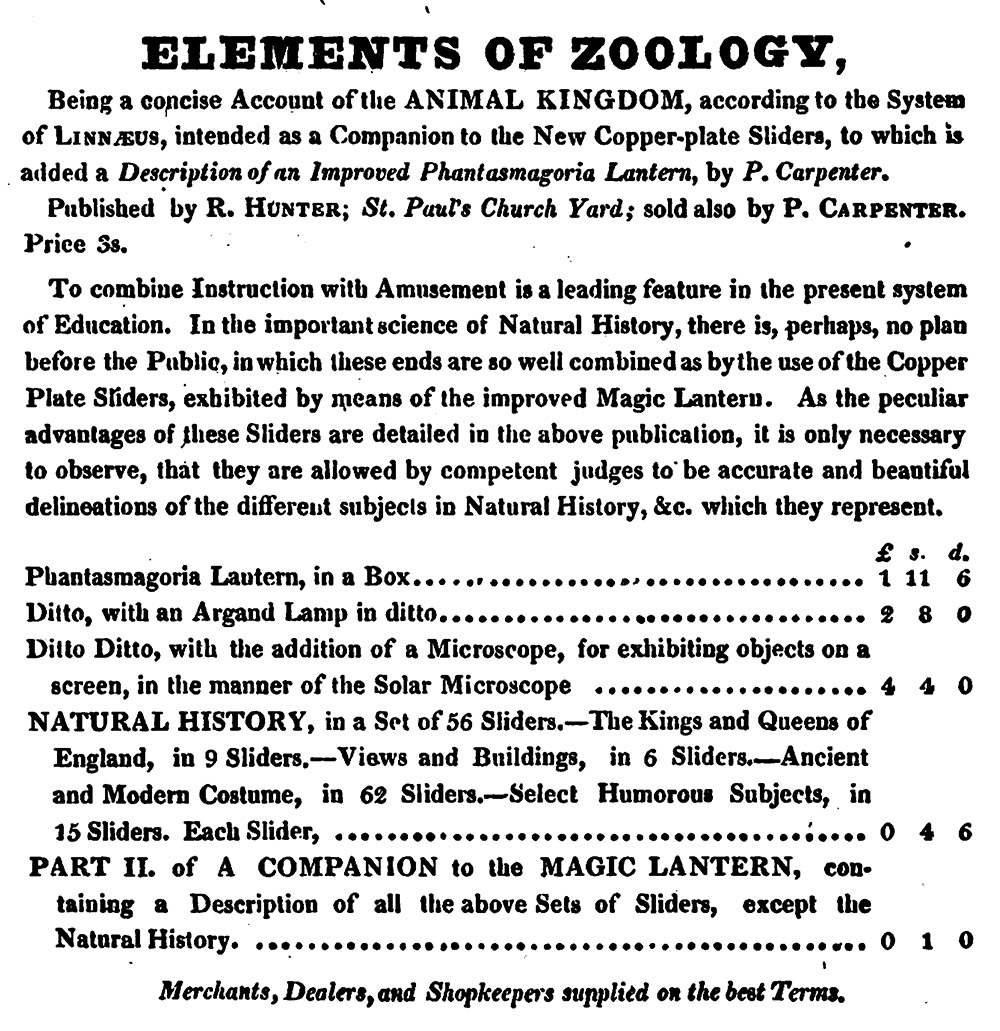

Figure 22.

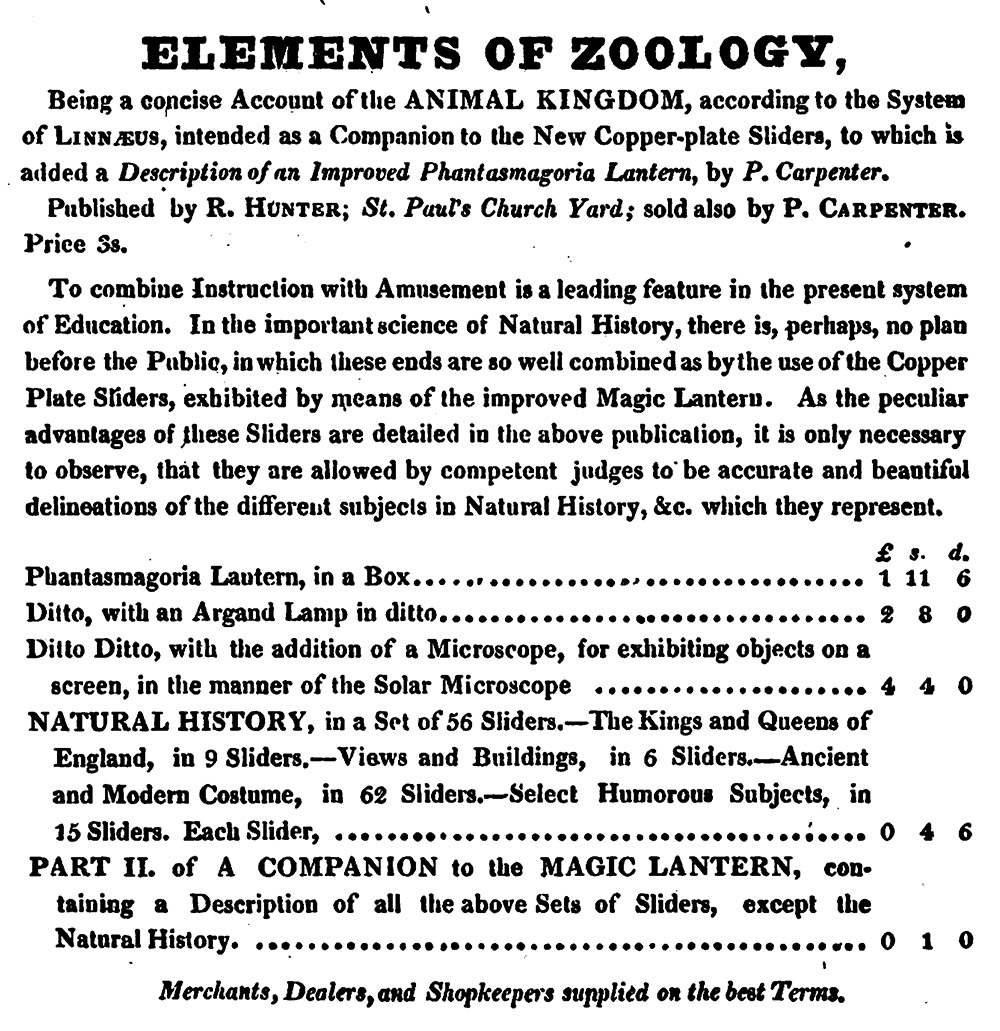

1827 catalogue of items for sale at Philip Carpenter’s shop at 24 Regent Street, London. Note that Carpenter promoted the sale of his goods to other “merchants, dealers, and shopkeepers”. Microscopes and other items are often encountered that look like those manufactured by Carpenter but are either unsigned or bear other people’s names, which likely came from wholesale distribution by Carpenter. From his “A Companion to the Microcosm”.

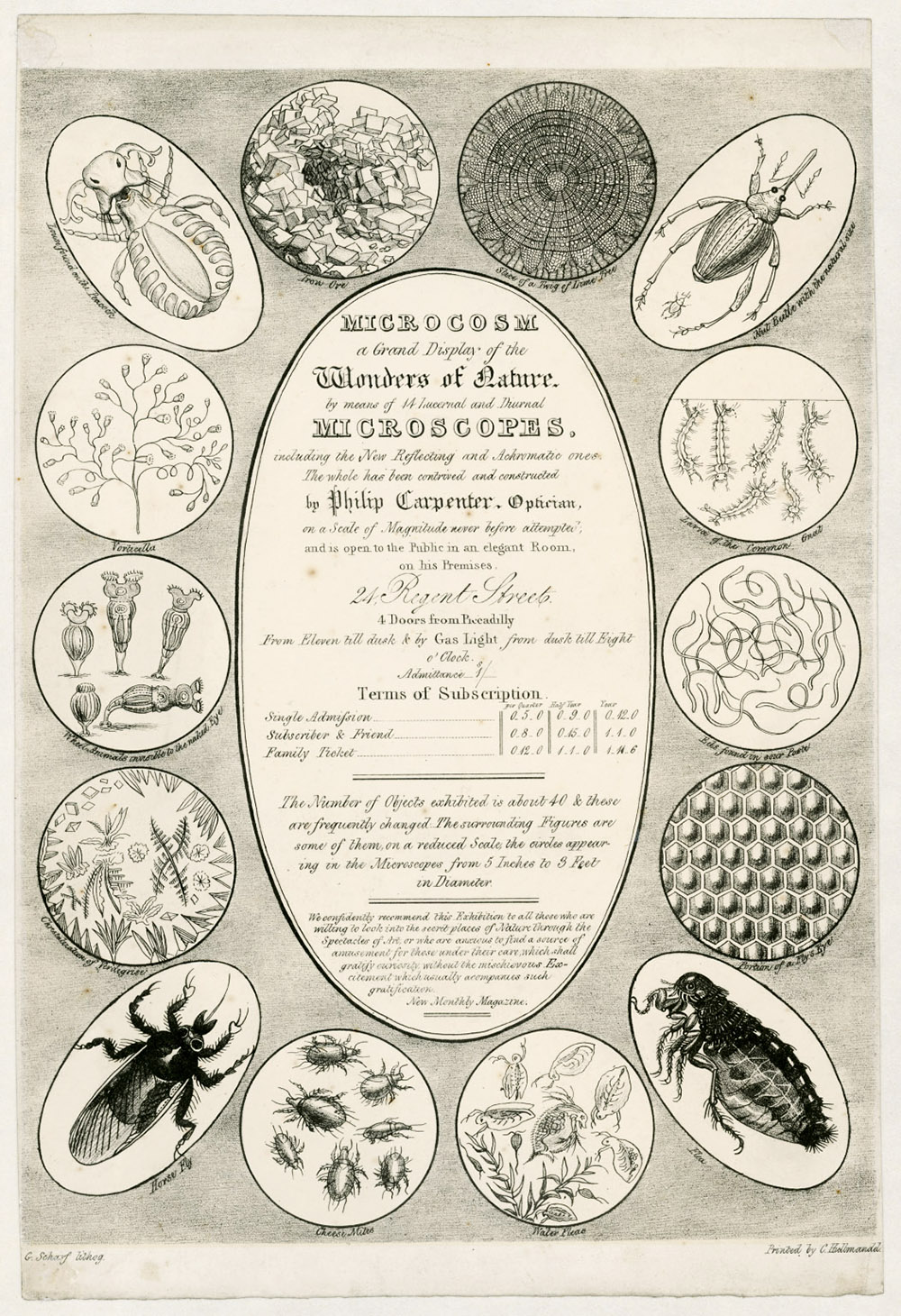

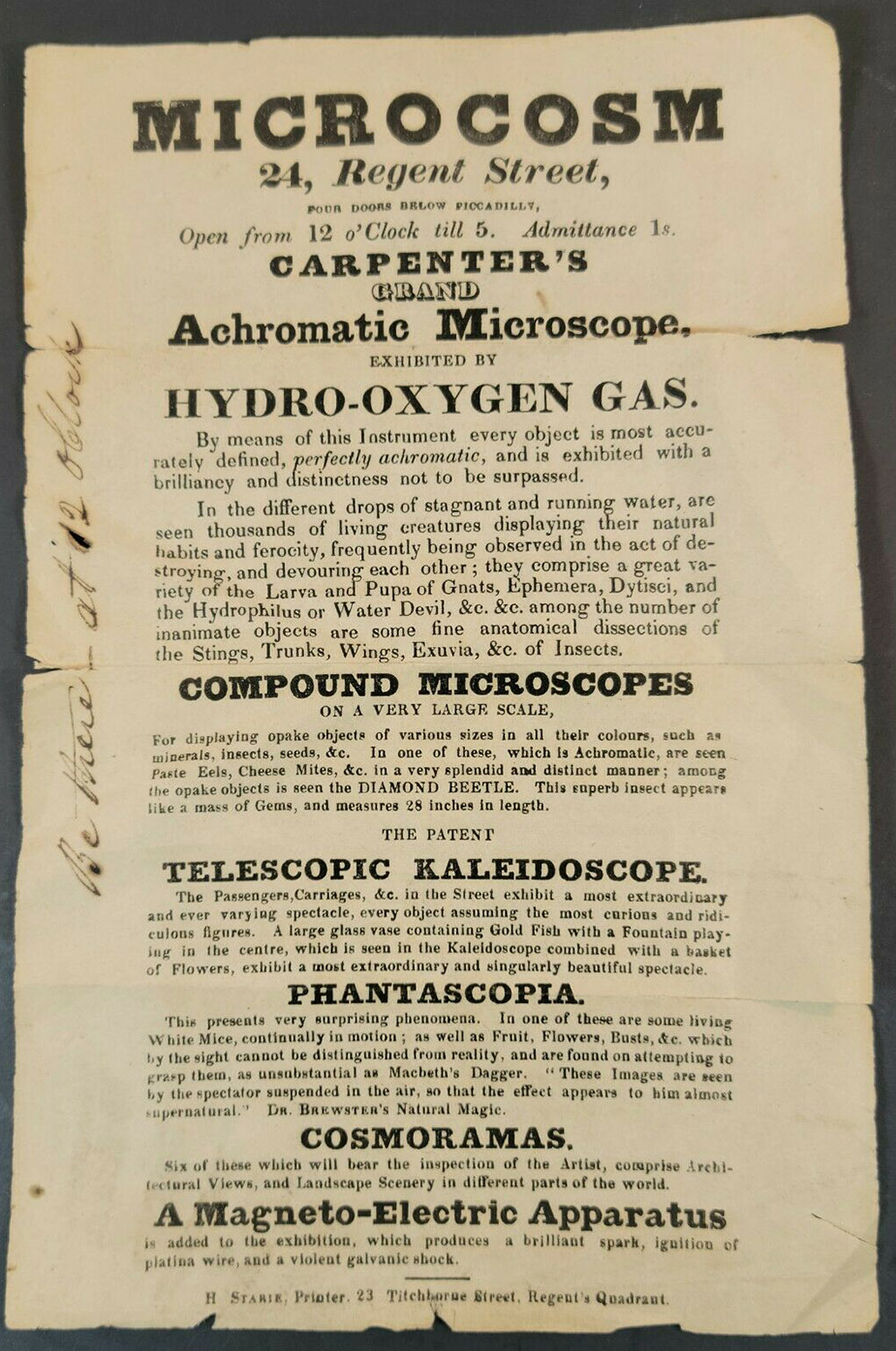

Figure 23.

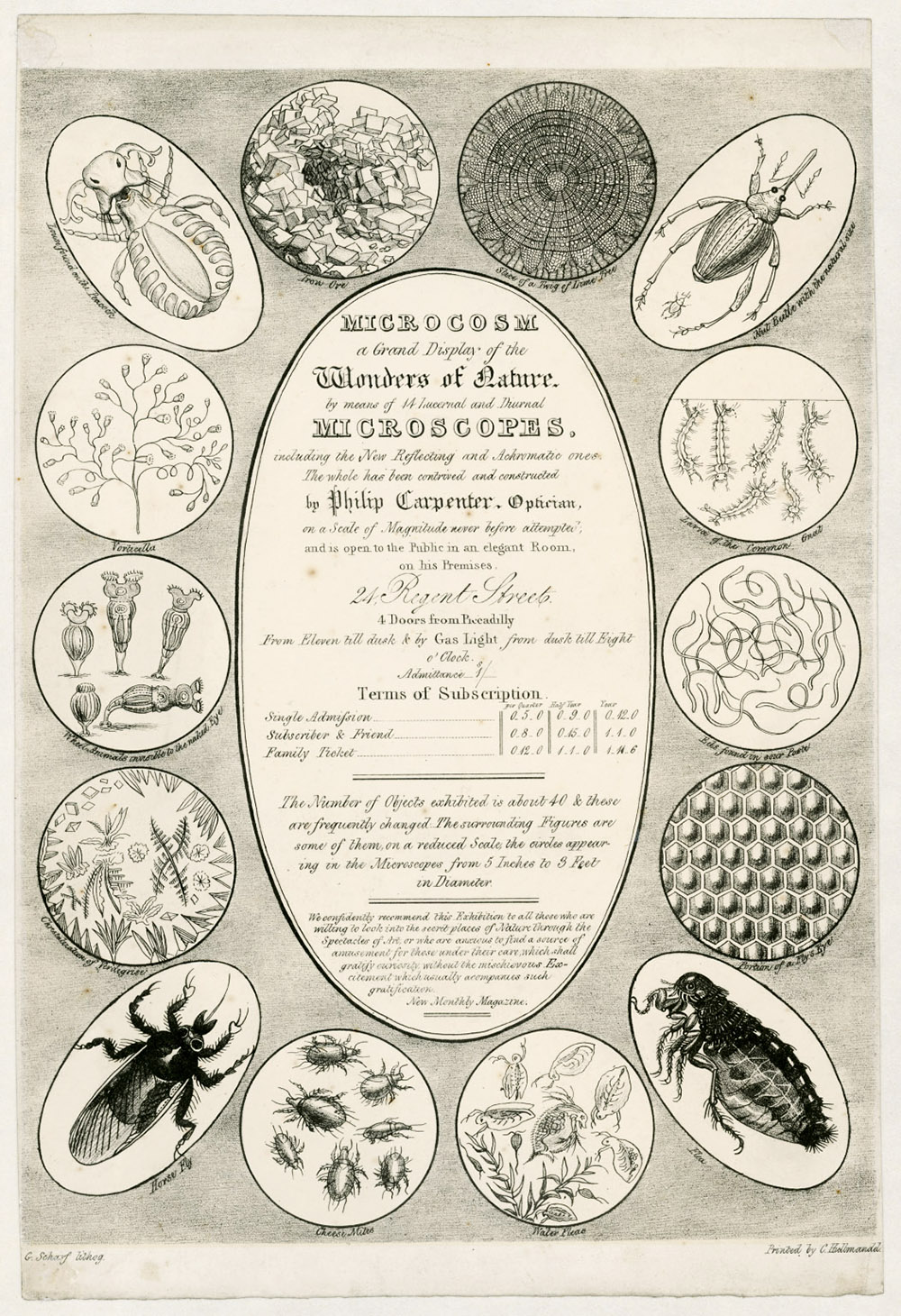

A ca. 1826 advertisement for Philip Carpenter’s “Microcosm”. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes.

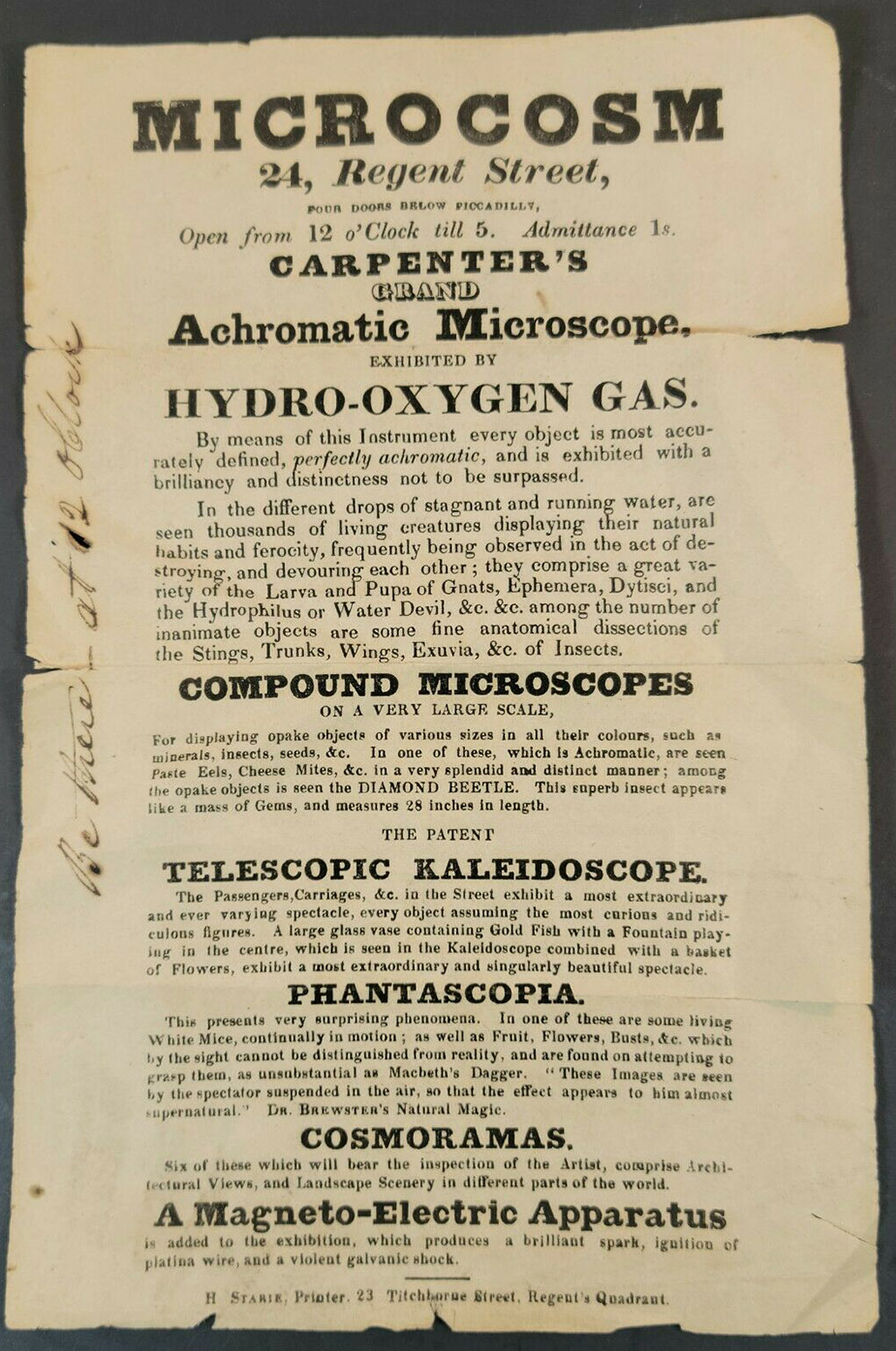

Figure 24.

A ca. 1826 advertising flier from Philip Carpenter. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes.

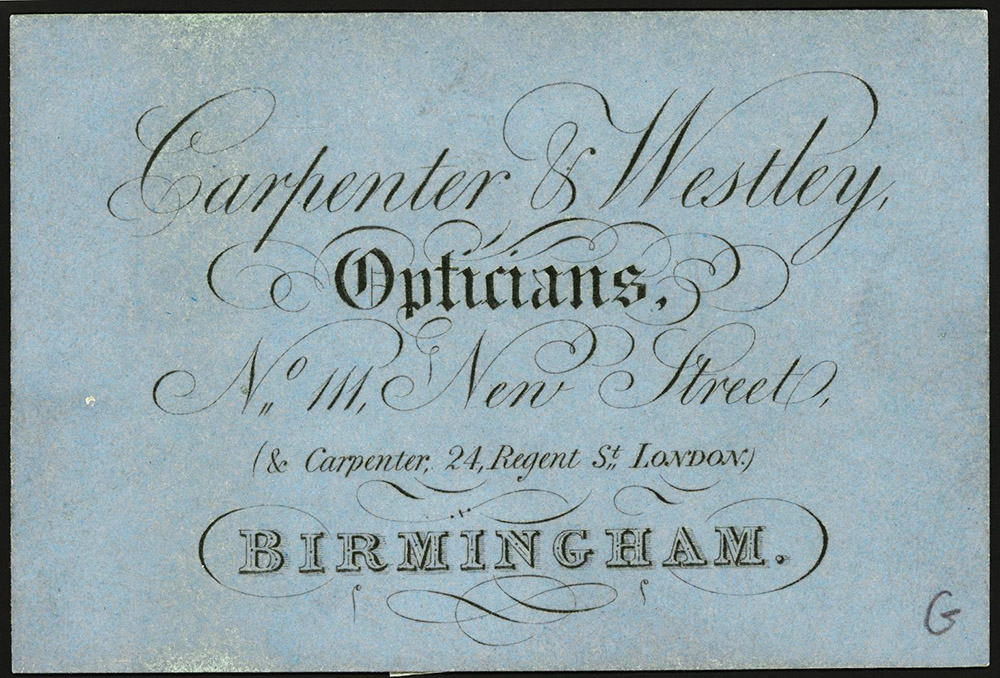

Figure 25.

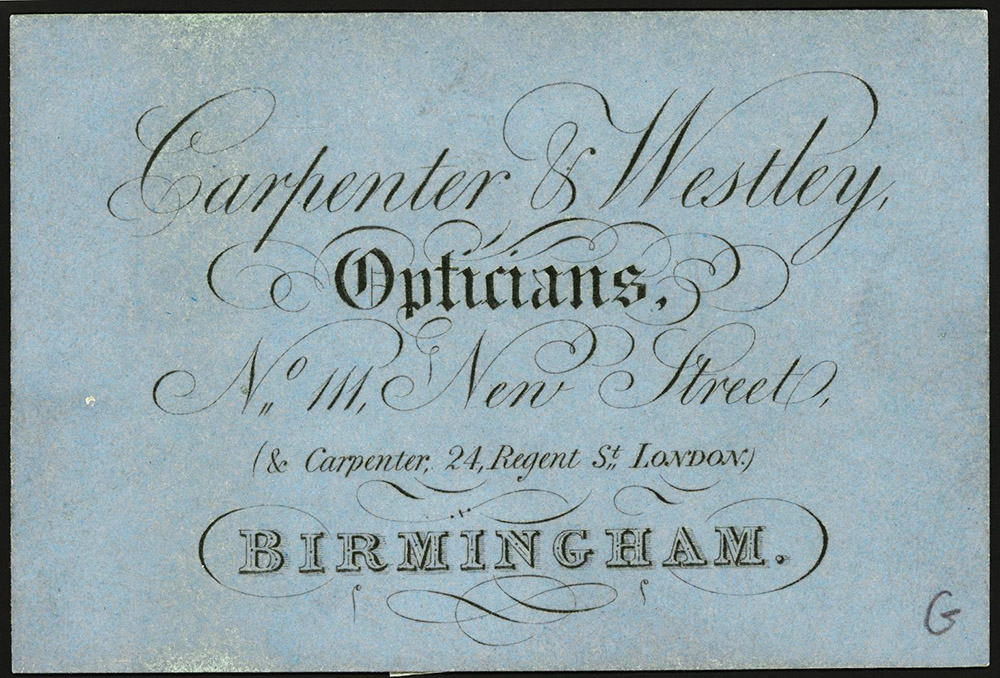

1830s trade card. Note that the Birmingham branch was named “Carpenter & Westley”, while the London branch was simply “Carpenter”. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co8015902/trade-card-carpenter-westley-111-new-st-birmi-trade-card

Figure 26.

An 1838 advertisement from Carpenter and Westley, from “Arcana of Science”.

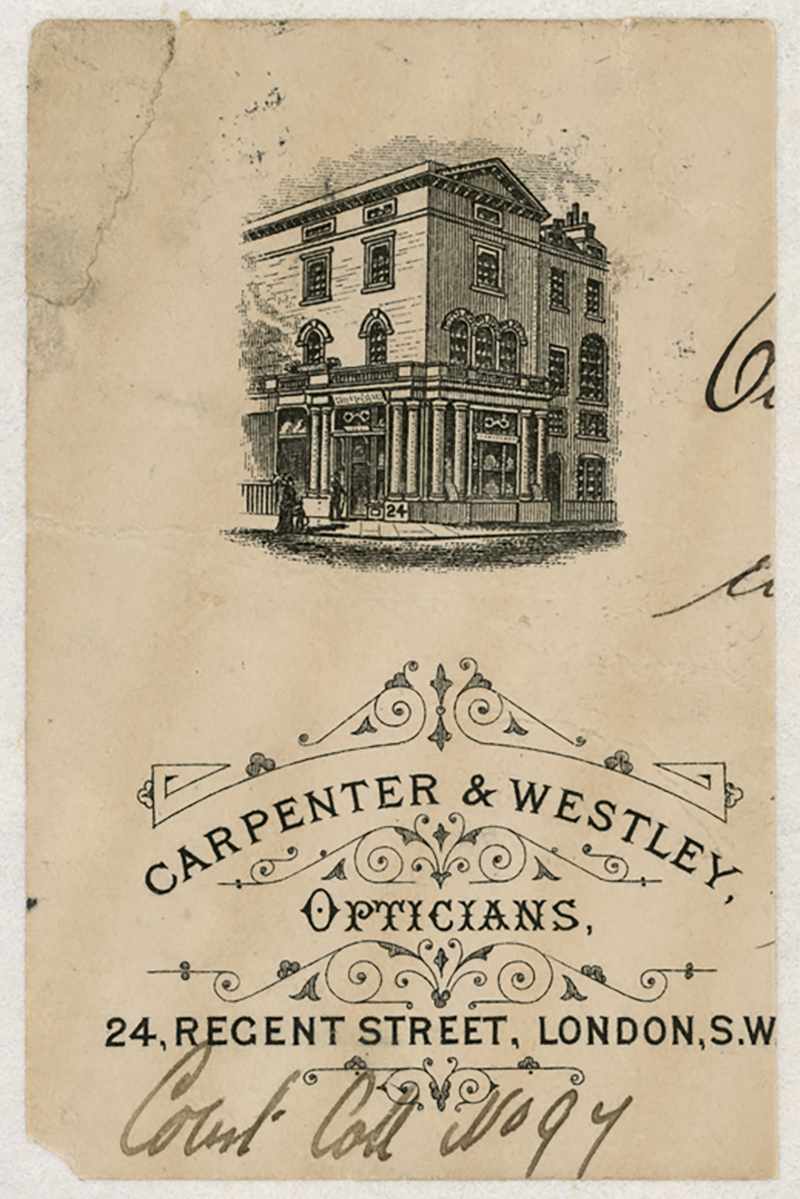

Figure 27.

Mid-1800s illustration of the Carpenter and Westley shop/home at 24 Regent Street. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co8002170/carpenter-westley-trade-card-trade-card

Figure 28.

Three ca. 1850 lantern slides, each with “Carpenter & Westley, 24 Regent St, London” stamped into the wood frames. They contain balsam-mounted specimens (upper left) three small crabs, (upper right) swallowtail butterfly, and (bottom) a lanternfly. The hardwood frames measure 7 x 3 ¾ inches (17.5 x 9.5 cm), with glass discs that are 3 inches (7.6 cm) in diameter.

Figure 29.

A mid-1800s “copperplate” lantern slide by Carpenter and Westley. The outline of the design was printed onto the glass disc, which was then hand painted. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/0e/Magic_lantern_slide_Carpenter_and_Westley.jpg

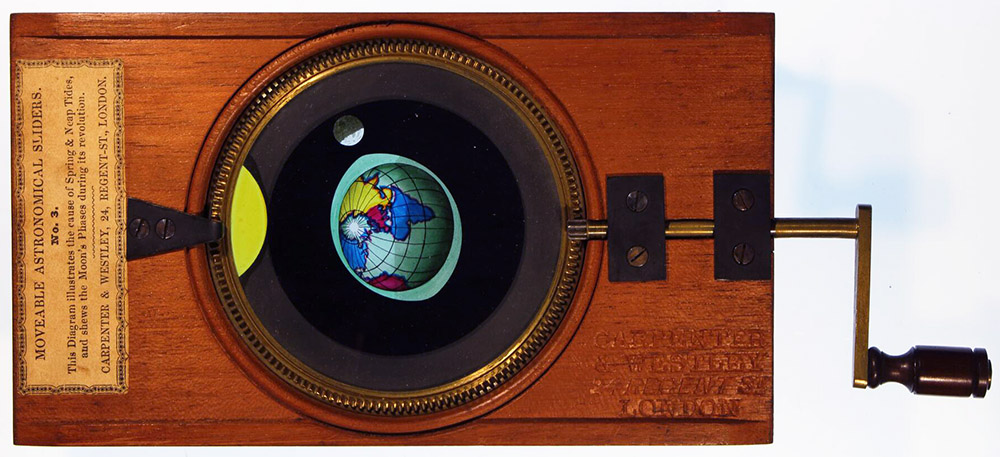

Figure 30.

Mid-1800s “copperplate” lantern slide with mechanical action, by Carpenter and Westley. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://www.arts.kuleuven.be/cultuurgeschiedenis/afbeeldingen/movable-astronomical-slide-from-carpenter.jpg

Figure 31.

Pocket barometers by Carpenter and Westley, mid- to late-1800s. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from internet auction sites.

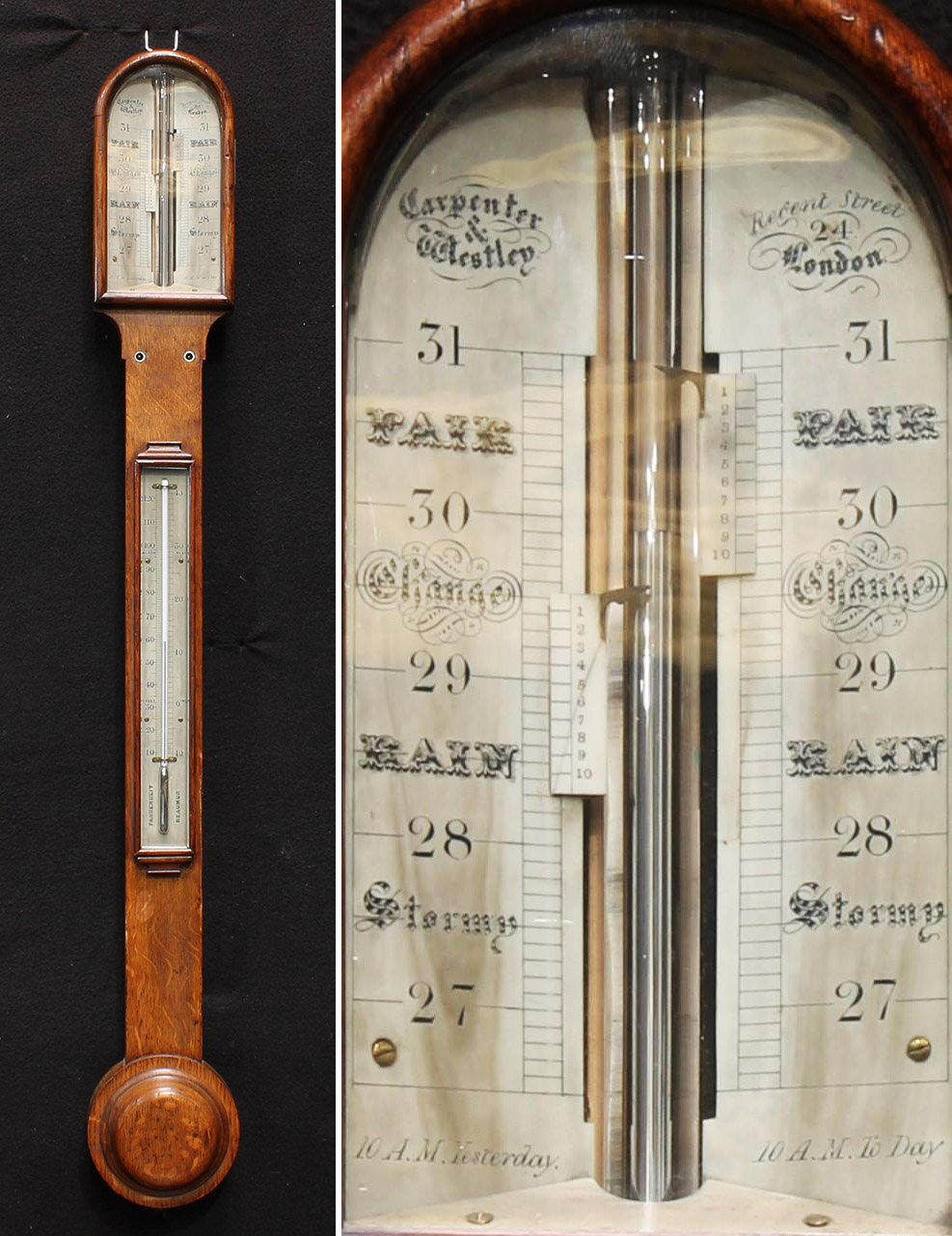

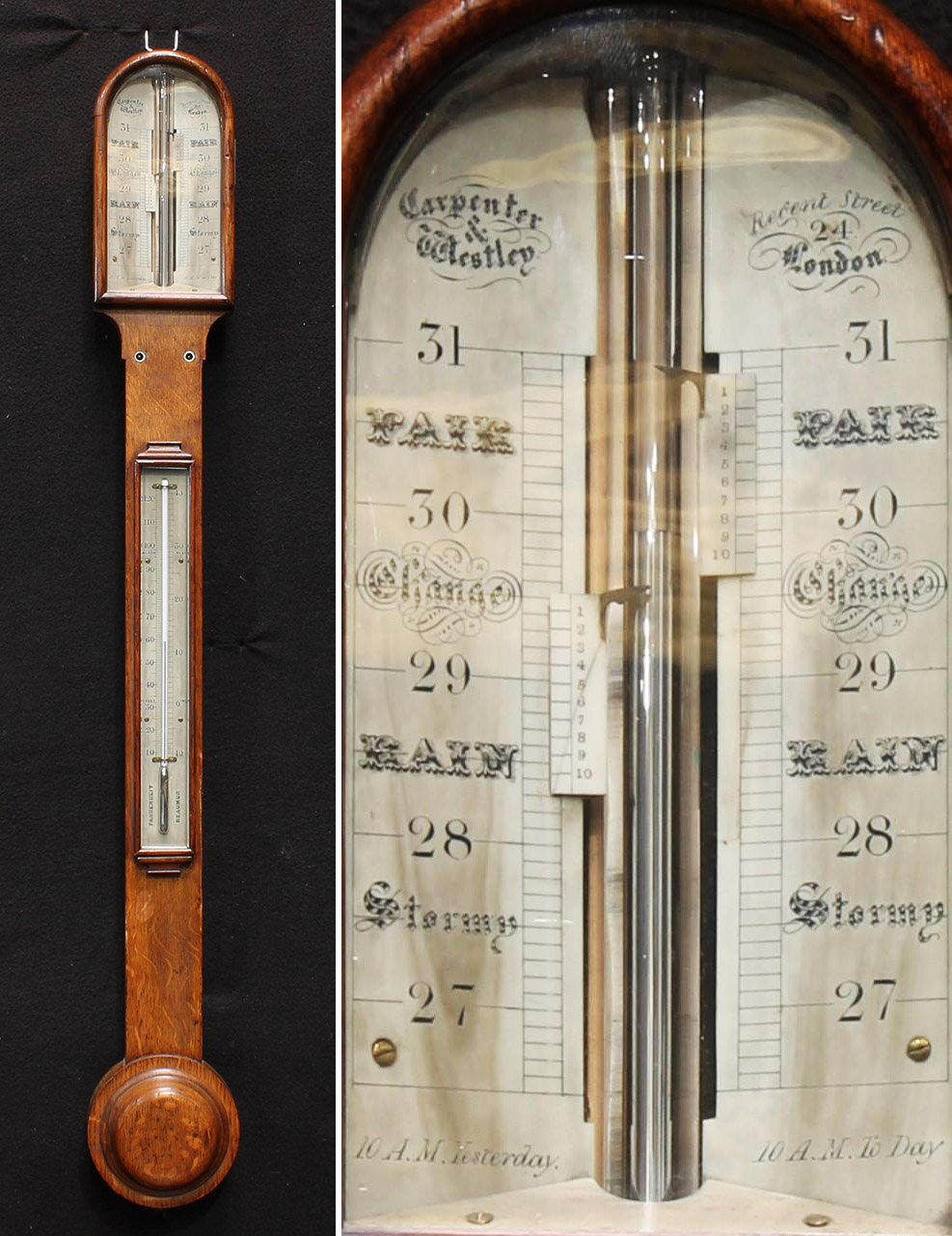

Figure 32.

A wall-mounting barometer by Carpenter and Westley, mid- to late-1800s. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Figure 33.

An 1890 advertisement, from “The Ophthalmic Review”.

Figure 34.

Two glasses cases. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from internet auction sites.

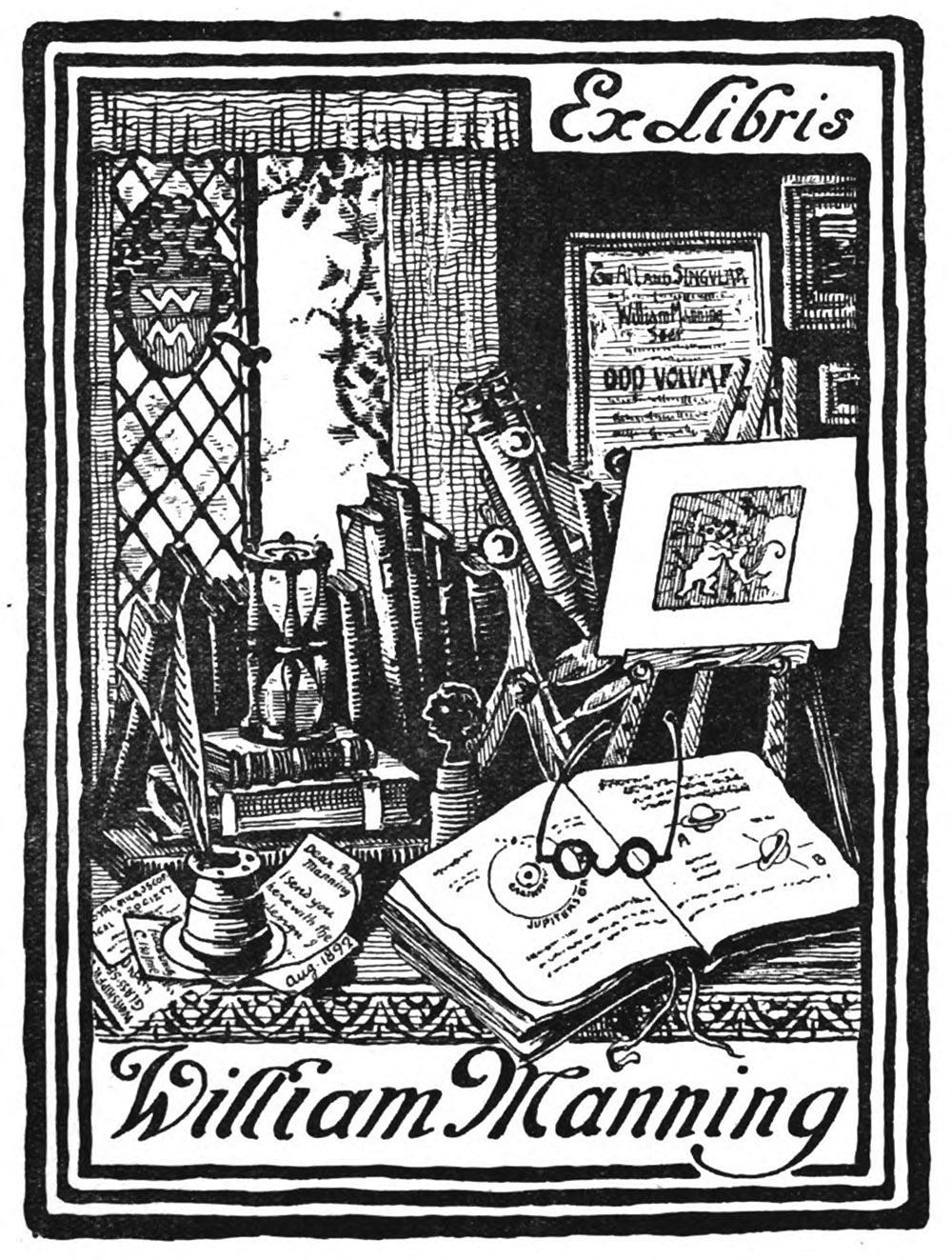

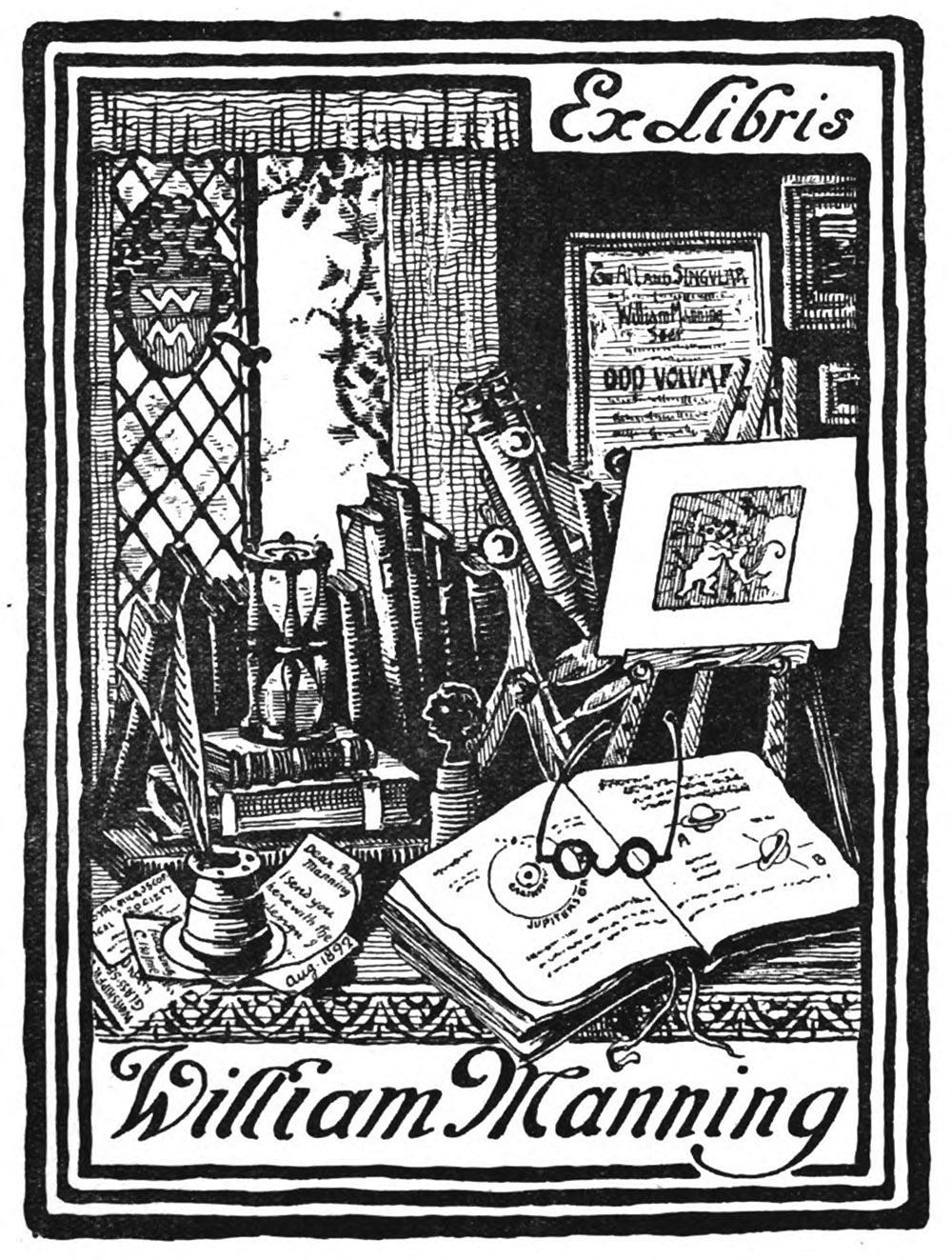

Figure 35.

William Manning’s bookplate. Note the eyeglasses and microscope (Manning was a Fellow of the Royal Microscopical Society). From “Journal of the Ex Libris Society”, 1899.

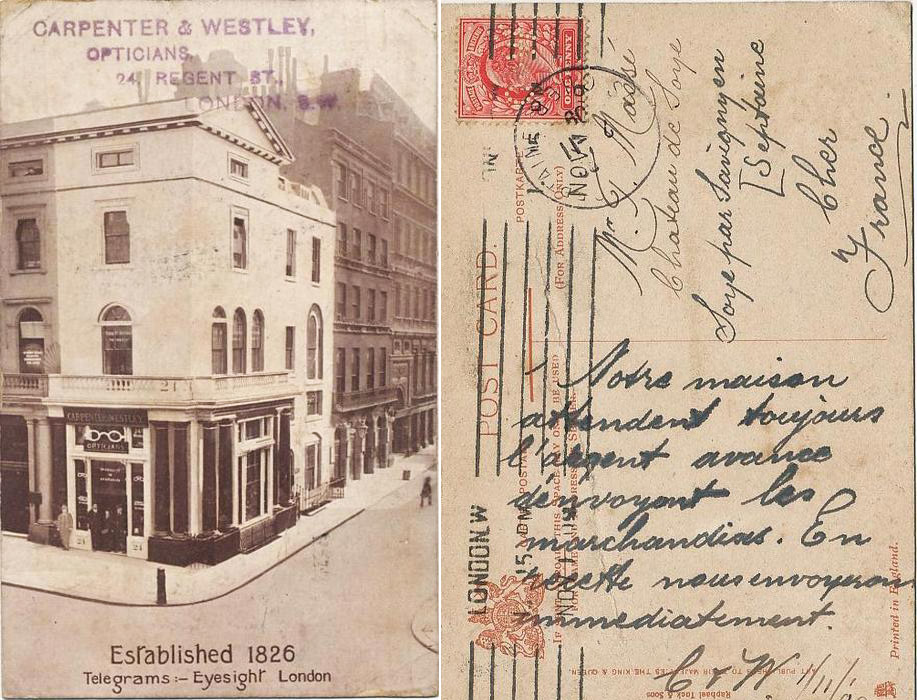

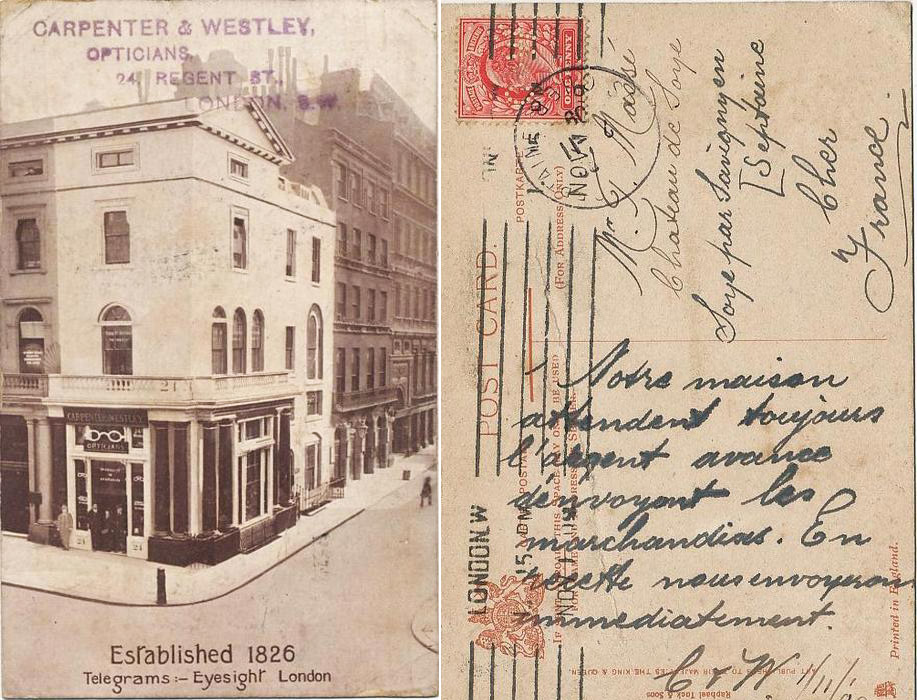

Figure 36.

24 Regent Street, 1909. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://tuckdbpostcards.org/items/135810

Acknowledgement

Thank you to Joe Zeligs for helpful discussions during production of this essay.

Resources

Arcana of Science (1838) Advertisemnt from Carpenter and Westley

Barnes, John (1984) Philip Carpenter 1776-1833, The New Magic Lantern Journal, Vol. 3, No. 2, pages 8-9

Bates, Robert (1818) History of Dr. Brewster’s Kaleidoscope, The Repertory of Arts and Manufacture, Vol. 33, pages 145-160

Beattie, Trevor (2013) Carpenter and Westley, their history and artistry, The New Magic Lantern Journal, Vol. 11, No. 4, pages 6-10

Baptism record of George Carpenter (1747) accessed through ancestry.com

Baptism record of William Manning (1834) Parish records of St. Martin Church, Birmingham, accessed through ancestry.com

Baptism record of William Westley (1807) Parish records of St. Martin Church, Birmingham, accessed through ancestry.com

Bracegirdle, Brian (1998) Microscopical Mounts and Mounters, Quekett Microscopical Club, London, pages 20, 122, and 192, and plates 9-C and 44-H

Brewster, David (1819) A Treatise of the Kaleidoscope, A. Constable & Co., Edinburgh

Carpenter, Philip (1827) A Companion to the Microcosm, Carpenter, London

Carpenter, Russell Lant (1842) Memoirs of the Life of the Rev. Lant Carpenter, LL. D., Greene, London

The Christian Life (1882) Review of Remarkable Women by Ann Swaine, Vol. 8, page 461

The Christian Reformer (1843) Memoriam of Thomas Hooke Carpenter, page 539

Cooper, Daniel (1841) A brief sketch of the rise and progress of microscopic science, Microscopic Journal and Structural Record for 1841, Vol. 2, pages 1-4

Drake, James (1837) “Opticians (Working), and manufacturers of spectacles, optical and mathematical instruments … Field Robert, 111, New Street, and 33, Navigation street”, The Picture of Birmingham, Third edition, page 133

England census and other records, accessed through ancestry.com

Haydon, Benjamin Robert (1830) Description of Eucles, includes 4 pages of advertisements from Philip Carpenter’s London Microscosm

Henry, David (1984) The pieces fit, The New Magic Lantern Journal, Vol. 3, No. 1, pages 8-9

London Gazette (1783) Bankruptcy of George Carpenter, June 3 issue, page 6

London Gazette (1789) Bankruptcy of George Carpenter, March 21 issue, page 160

London Gazette (1803) Dissolution of the partnership between Thomas Ryland and Philip Carpenter, April 121 issue, page 439

Nuttall, R.H. (1976) Philip Carpenter and the ‘Microcosm” exhibition; with a note on Carpenter & Westley’s microscopes, Quekett Journal, Vol. 33, pages 62-65

Osborne's Guide to the Grand junction, or Birmingham, Liverpool and Manchester Railway (1838) Advertisements from Thomas Hooke Carpenter, page 24

Pigot and Co.'s Classified Directories of the Merchants, Manufactures, and Wholesale Traders in Birmingham, Carlisle, Hull, Leeds, Liverpool, Manchester, Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, and Sheffield (1837) “Birmingham … Opticians … Field Robert, 33 Navigation st … Spectacle Makers … Carpenter & Westley, 11 New st”, pages 22 and 27

Pigot's Directory of Warwickshire (1816) “Opticians … Carpenter Philip, Bath-row”, page 30

Pigot's Directory of Warwickshire (1818) “Opticians … Carpenter Philip, Bath-row”, page 48

Pigot's Directory of Warwickshire (1821) “Opticians … Carpenter Philip, 11 New st”, page 800

Pigot's Directory of Warwickshire (1822) “Opticians … Carpenter Philip, Bath-row”, page 519

Pigot and Company’s National Commercial Directory (1828) “Birmingham … Opticians … Carpenter Philip 111 New st.”, page 800

The Post Office London Directory (1843) “Carpenter & Westley, opticians, Microcosm, 24 Regent street … Westley William, optician, see Carpenter & Westley”, pages 120 and 425

The Post Office London Directory (1843) Advertisement from Carpenter & Westley, page 1626

Quekett, John (1852) A Practical Treatise on the Use of the Microscope, includes advertisement from Carpenter and Westley

Roberts, Phillip (2016) Building media history from fragments: a material history of Philip Carpenter’s manufacturing practice, Early Popular Visual Culture, Vol. 14, pages 319-339

Roberts, Phillip (2016) The early life of Philip Carpenter, The Magic Lantern, Vol. 6, pages 10-13

Roberts, Phillip (2017) Philip Carpenter and the convergence of science and entertainment in the early-nineteenth century instrument trade, Science Museum Group Journal, 10.15180; 170707, http://journal.sciencemuseum.ac.uk/browse/issue-07/philip-carpenter-and-the-convergence-of-science/

Talbot, Stuart (2007) The perfectionist projectionist, The New Magic Lantern Journal, Vol. 10, No. 3, pages 49-51

Timmins, Samuel (1866) The Resources, Products and Industrial History of Birmingham and the Midland Hardware District, R. Hardwicke, London, page 534

West, William (1830) “Birmingham … Carpenter Philip, optician, 111, New-st … Field Robert, spectacle maker and optician, 33, Navigation-st.”, The History, Topography and Directory of Warwickshire, pages 318 and 333

Will of Thomas Hooke Carpenter (1843) accessed through ancestry.com

Will of Philip Carpenter (1833) accessed through ancestry.com

Wrightson's Triennial Directory of Birmingham (1815) “Carpenter Philip, optician, Bath Row”, page 24

Wrightson's Triennial Directory of Birmingham (1823) “Carpenter Philip, optician, 111, New-street, and Bath Row”, page 27