Louis-Vincent Chevalier, 1743-1805

Jacques Louis Vincent (Vincent) Chevalier, 1770-1841

Charles Louis (Charles) Chevalier, 1804-1859

Louis Marie Arthur (Arthur) Chevalier, 1830-1874

René Gabriel Avizard, 1853 - after 1908

Charles Xavier Avizard, 1855 - after 1912

by Brian Stevenson

last updated July, 2025

During the 1800s, there were two important families of similarly-named microscope-makers in Paris. The subjects of this essay, the Chevaliers (1 “L”) began their business in 1765, on Quai de l’Horloge. An unrelated optical craftsman, J.G.A. Chevallier (2 “L”s), opened a competing shop on the same street in 1796. The businesses of J.G.A. Chevallier and his successors, Victor Ducray-Chevallier, and P.M.A. Chevallier / Amédée Queslin / A. Fontana are covered elsewhere on this site.

Louis-Vincent Chevalier opened his optician’s business in 1765, after completing an apprenticeship with a mirror-maker. Following his death in 1805, his son Vincent continued the shop. A younger son, Jean Louis Joseph Chevalier (best known as Louis Chevalier) opened an optical shop nearby, which became "L. Chevalier et Fils" after 1848. One of Louis' sons, Victor Chevalier, opened his own optican's shop ca. 1832. Illustrated biographies of Louis and Victor Chevalier are presented elsewhere on this site.

Vincent Chevalier became known for optical items such as cameras lucida and cameras obscura, and likely also produced some microscopes. In 1823, Vincent and his son, Charles, were enlisted by an optical engineer, Alexandre François Gilles (better known by the nickname “Selligue”) to produce an achromatic microscope to Selligue’s specifications. Upon its unveiling in 1824, the Chevaliers were angered that Selligue had not given them public credit. Moreover, they conceived a different combination of lenses that provided better achromatic vision. The Chevaliers named this new version after Léonard Euler, an early optical theorist who had worked to develop achromatic lens combinations. Use of that name was probably a jab at Selligue, implying that he had not actually created a new invention.

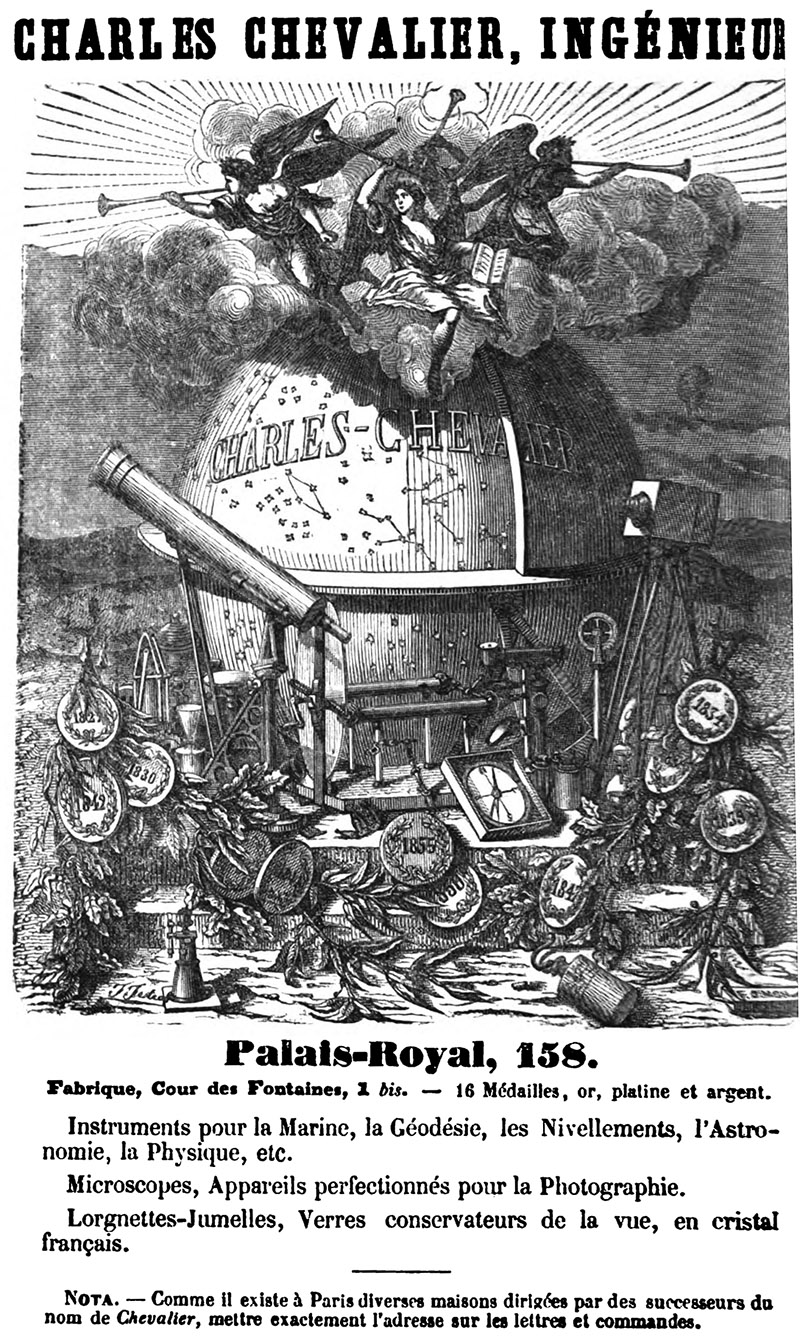

In 1833, Charles Chevalier had become tired of not receiving adequate credit for his work with Vincent, and left to open his own optical business at Palais Royal (this date is based on Charles’ statements in his 1839 book Des Microscopes et de Leur Usage - later writings by Charles’ son and others gave dates of 1830 or 1832 - I will favor Charles’ own words). Once the palace of Cardinal Richelieu, Palais Royal had been developed into an elegant shopping and social center, housing numerous businesses. Charles and Vincent maintained independent businesses until Vincent’s death. Charles’ creativity led to numerous optical and mechanical developments, and a vast expansion in the styles of microscopes offered. During this period, Vincent’s production of microscopes largely followed his designs of the 1820s or of other manufacturers. Some modern authors have suggested that the father and son were at odds during the time of their separate shops, but I have not located any contemporary sources to support that notion. Vincent left his estate to Charles and another son, suggesting a relatively normal father-son relationship.

Charles’ inheritence of Vincent’s estate has apparently led some modern writers to assume that Vincent and Charles had worked together before the father’s death. However, all historical records indicate that Charles worked only from Palais Royal.

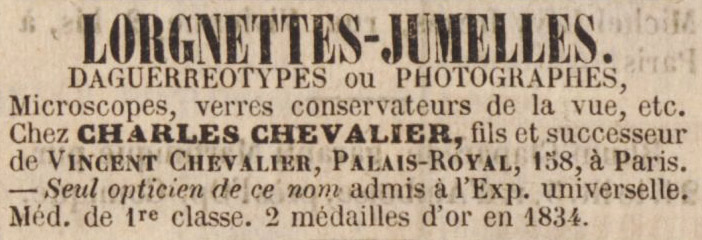

From 1841 onward, Charles advertised himself as “fils et seul successeur de Vincent Chevalier” (“son and sole successor of Vincent Chevalier”), while remaining at Palais Royale. However, an employee of Vincent’s, Pierre Ambroise Richebourg (1810-1875), took over Vincent’s shop on Quai de l’Horloge, and operated there for many years whiel describing himself as “le seul élève de Vincent Chevalier” (“the only student of Vincent Chevalier”).

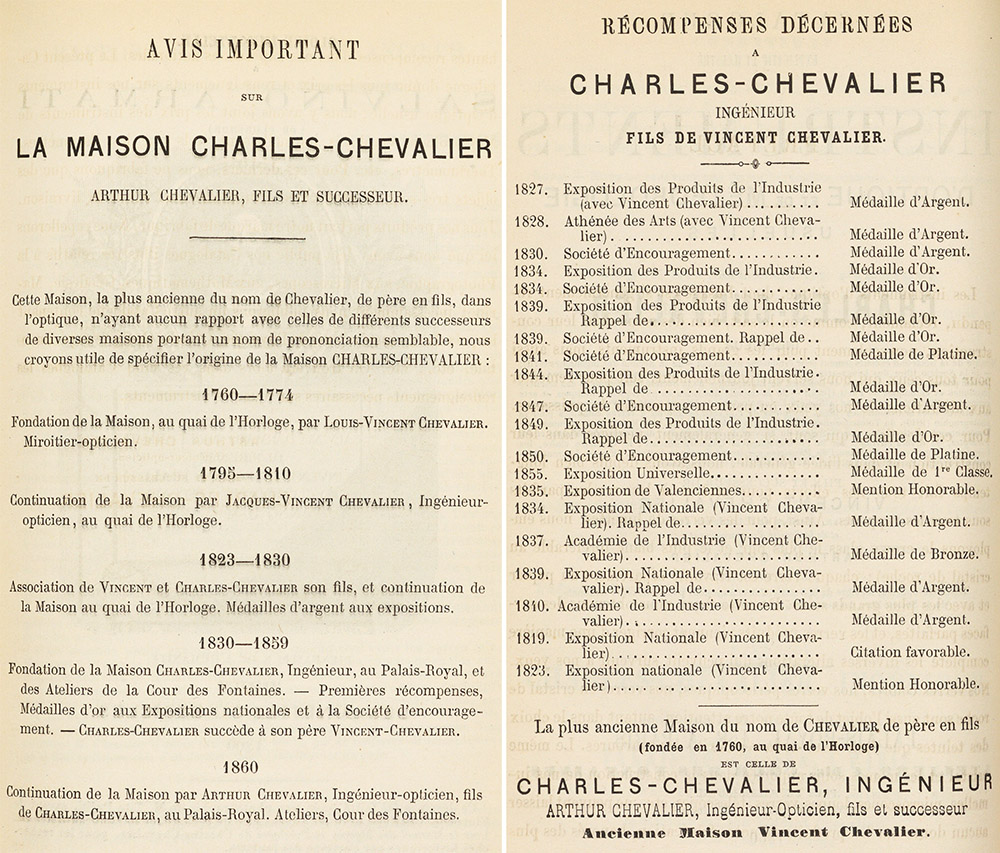

Of note, later advertisements from Charles and his son, Arthur, list the history of the Chevalier business as having passed from Vincent to Charles in the early 1830s without mention of Vincent’s independent 1833-1841 business. This modified business genealogy was probably intended to support Charles’ claim to be Vincent’s sole successor. Confessing that Vincent had a separate business would acknowledge that Richebourg was also a successor to Vincent’s business.

Upon Charles’ death in 1859, his son, Arthur, took over the business. Arthur was presented with an honorary doctoral degree from the University of Rostock in 1870, and subsequently referred to himself as “Dr. Arthur Chevalier”. This is an important point for establishing production dates for Arthur Chevalier’s microscopes.

Arthur Chevalier died in January, 1874, when only 43 years old. His widow died a month later. Ownership of the Chevalier business fell to their young daughters. They, too, rapidly succumbed to illness, the last one dying in 1880. The early deaths of Arthur, his wife, and their daughters, suggest a cummunicable infectious disease such as tuberculosis.

The Chevalier business was purchased in 1881 by two brothers, René and Charles Avizard, who owned other optical businesses. Perhaps not a coincidence, Charles Avizard had evaluated the estates of Arthur and his last daughter, and thus helped set the selling price. Two years later, in February, 1883, the Avizards bought the optical business that had been started by J.G.A. Chevallier (2 “LL”s). The Chevalier and Chevallier shops operated separately, under their old names, until ca. 1914-1921. Thus, a substantial number of microscopes that are marked with “Dr. Arthur Chevalier” were produced during the Avizard’s stewardship, and manufactured by contracted businesses.

Note: The Chevalier family, especially Charles, played significant roles in the development of photography. In keeping with the theme of this essay series on historical microscopists, I will focus primarily on the microscope aspects of the Chevaliers’ business.

A detailed history of the Chevalier family and their businesses is presented below, following illustrations and descriptions of their microscopes.

Notable dates in the Chevalier businesses:

1765: Louis Vincent Chevalier established a shop on Quai de l’Horloge.

1805: Louis Vincent Chevalier died, Vincent Chevalier (“Chevalier fils”) continued the business. At 67 Quai de l’Horloge.

ca. 1820: Address became 69 Quai de l’Horloge.

1823-24: Vincent Chevalier, accompanied by Charles, produced his first known microscopes. These were achromatic instruments, initially produced in conjunction with “Selligue” (Alexandre François Gilles). From 1825 onward, they were produced to a different design (“Selon Euler”).

1826: Earliest known record of Vincent and Charles Chevalier as partners (“Vincent Chevalier aîné et fils”).

1829: The partners described their business as “Vincent et C. Chevalier”.

1833: Charles Chevalier left to open his own shop, at 163 Palais Royal. Vincent Chevalier continued at 69 Quai de l’Horloge.

1839: Camille Sébastien Nachet (1799-1881), who had manufactured microscope lenses for Charles Chevalier, opened his own business. Nachet initially manufactured achromatic objectives, which were used by several microscope manufacurers of the time. He went on to be a major producer of microscopes and other optical devices.

1841: Vincent Chevalier died. Charles Chevalier subsequently referred to himself as “seul successor de feu Vincent Chevalier” (“only successor to the late Vincent Chevalier”). The business at 69 Quai de l’Horloge was continued by Vincent’s employee, Pierre Ambroise Richebourg (1810-1875), who subsequently referred to himself as “seul élève de Vincent Chevalier” (“only student of Vincent Chevalier”).

1848: Address of Charles Chevalier’s shop changed from 163 Palais Royal to 163 Palais National.

1849: Address of the Chevalier shop changed from 163 to 158 Palais National.

1852: Palais National changed its name back to Palais Royal, so the address of Chevalier’s shop changed to 158 Palais Royal.

1859: Charles Chevalier died. The business was continued by Arthur Chevalier.

1870: Arthur Chevalier awarded an honorary doctoral degree from the University of Rostock, and subsequently referred to himself as “Dr. Arthur Chevalier”.

1874: Arthur Chevalier died. His wife and one of his daughters died one month later. The business was inherited by Arthur’s two surviving daughters, Adèle Marie Gabrielle and Marie Louise Charlotte Chevalier, and continued as “Dr. Arthur Chevalier”.

1880: Marie Louise Charlotte Chevalier died. Her sister, Adèle Marie Gabrielle, had evidently died earlier. The Chevalier business was aquired in 1881 by Charles and René Avizard, who continued to use the name “Dr. Arthur Chevalier”.

ca. 1914-1922: The “Chevalier” business was merged with that of “l’Engénieur Chevallier”, which the Avizards had aquired in 1883.

________________________________________________________________________

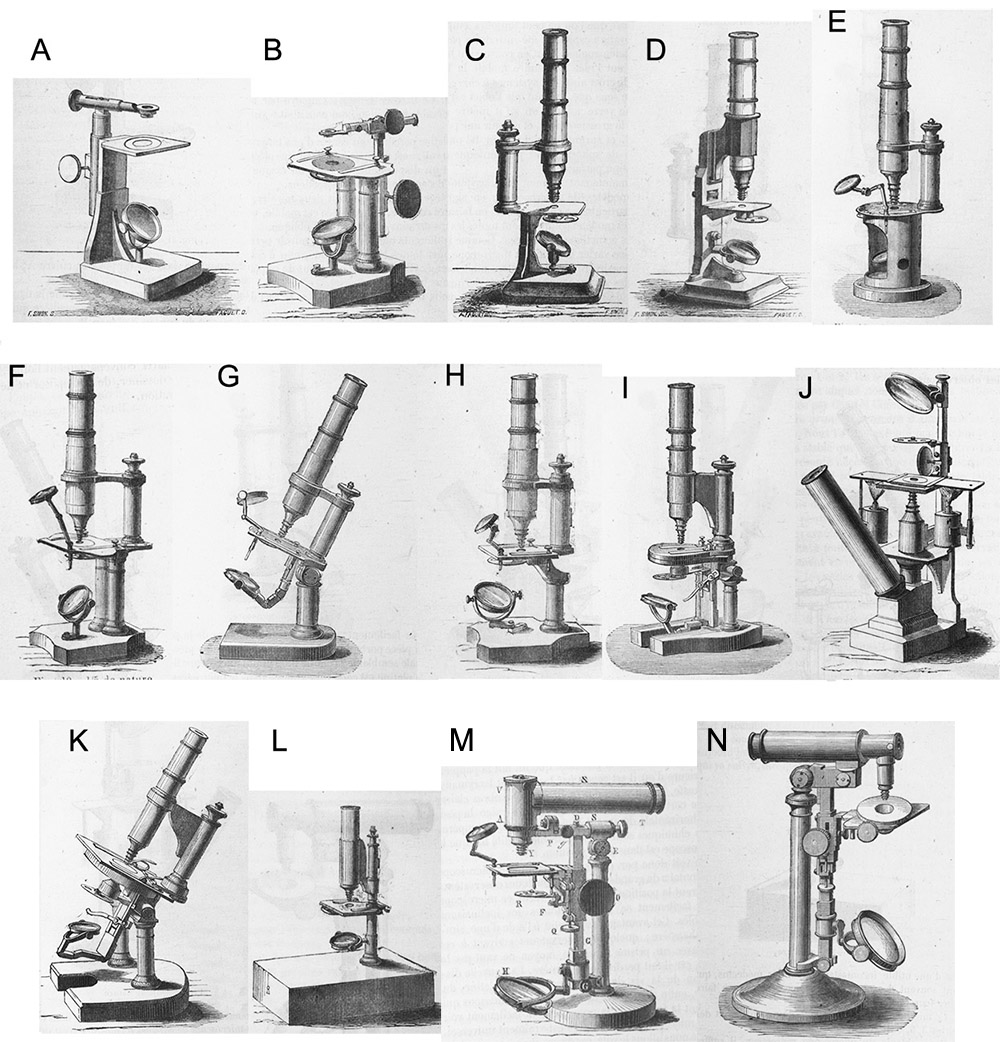

Examples of Chevalier microscopes, in approximate chronological order

Vincent Chevalier, 1805 - ca. 1826

After taking over the business from his father in 1805, Vincent intially added the phrase “fils” (“son”) to his name. That usage ended around 1809. By 1819, however, he was amending his name with “aîné” (“elder”), probably to clarify the relationship with his younger brother, Louis Chevalier, who opened an independent optical shop on the same street in 1818.

Vincent Chevalier appears to have produced microscopes prior to 1823. An old-style microscope, signed “V. Chevalier aîné”, is shown in Figure 1, and likely was made soon after 1818. It is certain that Vincent made two early contributions of note to other aspects of optical engineering: a camera lucida in 1819 and a camera obscura in 1820. In 1819, Vincent earned a Citation at the Exposition des Produits de l’Industrie for “divers instruments d’optique”, and an Honorable Mention at the 1823 Exposition for “instruments d’optique - aérometres de toute espèce, caféomètres et lactomètres”.

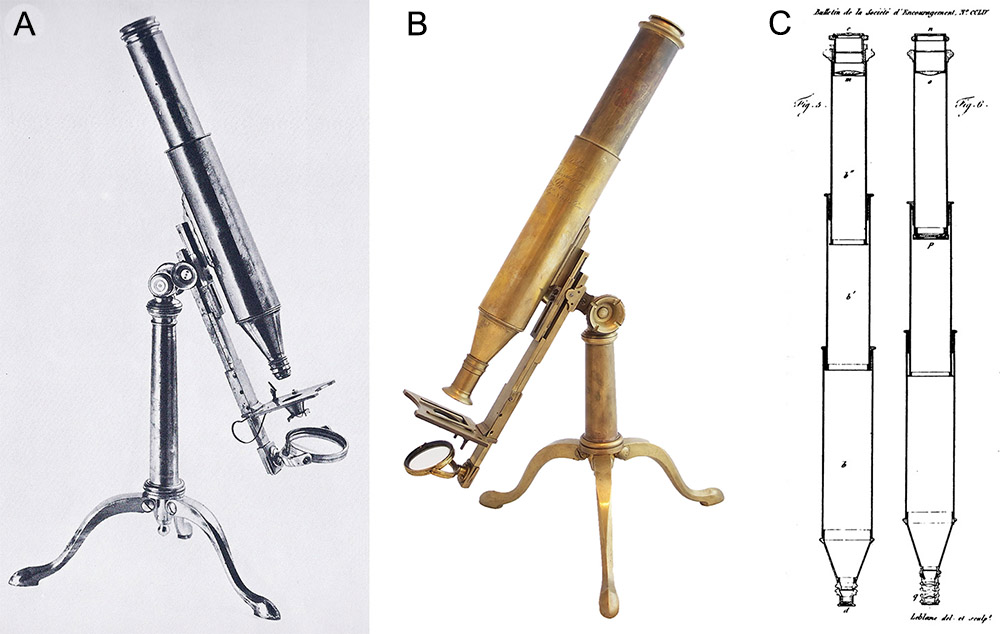

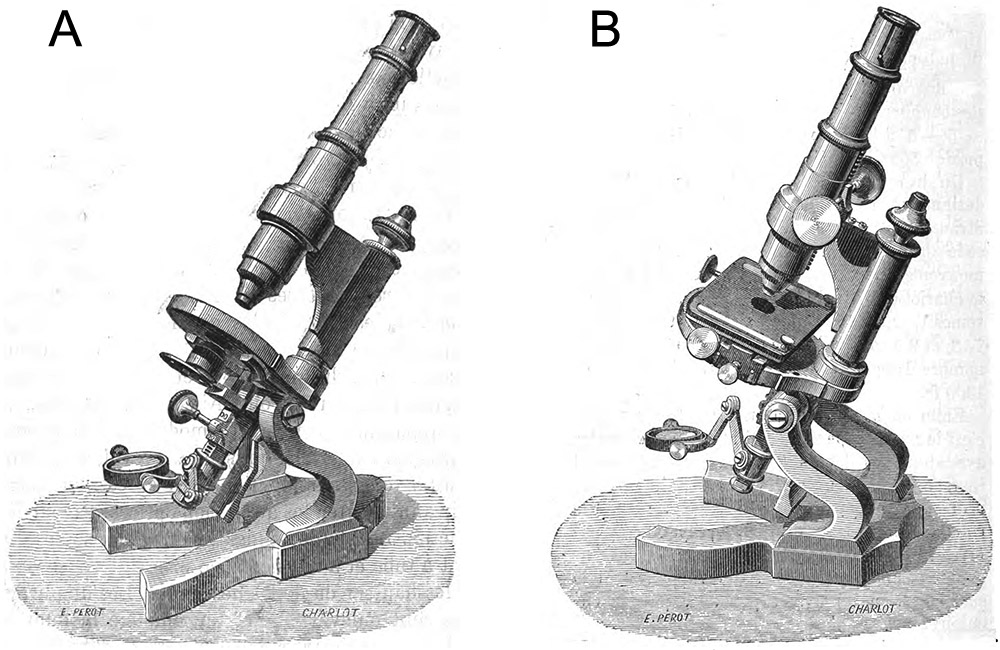

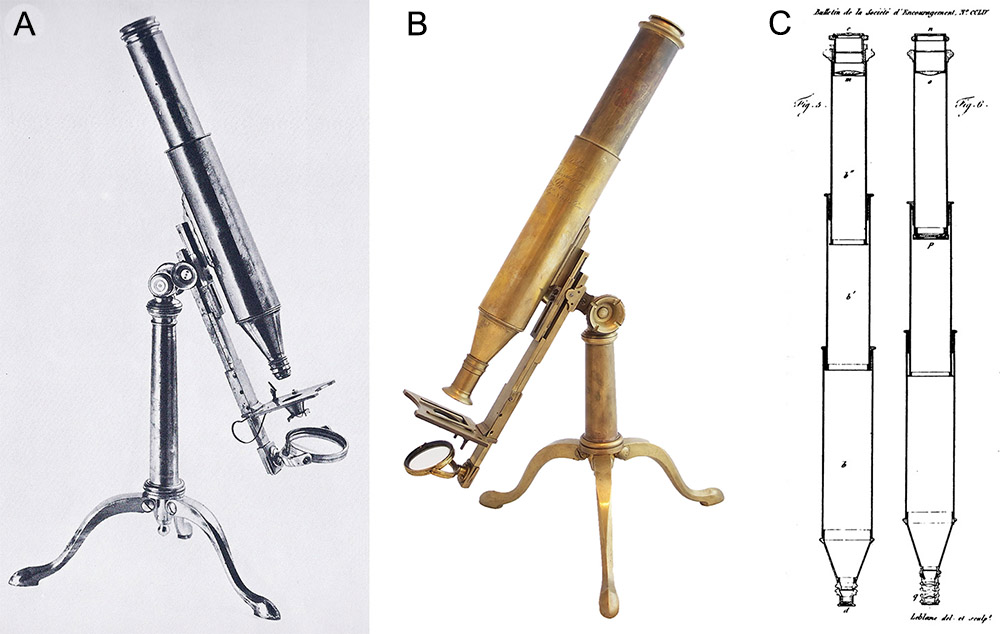

Toward the end of 1823, the Chevaliers were enlisted by Alexandre François Gilles (a.k.a. “Selligue”) to produce an achromatic microscope to his design. The first of these was presented to the Academy of Sciences of Paris in August, 1824. The instruments shown in Figure 2A and B are examples of this initial achromatic microscope.

The 1824 report on the achromatic microscope design failed to mention the Chevalier’s contribution, an omission that led to a split between the Chevaliers and Selligue. Additionally, the Chevaliers determined that a different arrangement of lenses in the objective provided better achromatic vision. They marketed their version as “microscope achromatique selon Euler” (“achromatic microscope in the style of Euler”), named after Léonard Euler (1707-1783), who had earlier theorized on achromatic lens combinations. Adopting Euler’s name may also have been a dig against their former colleague, implying that Selligue had not actually developed anything new.

The first “selon Euler” achromatic microscope was presented by Vincent Chevalier to the Academy of Sciences on March 30, 1825.

After ca. 1826, the business came to be known under the names of both Vincent and Charles Chevalier.

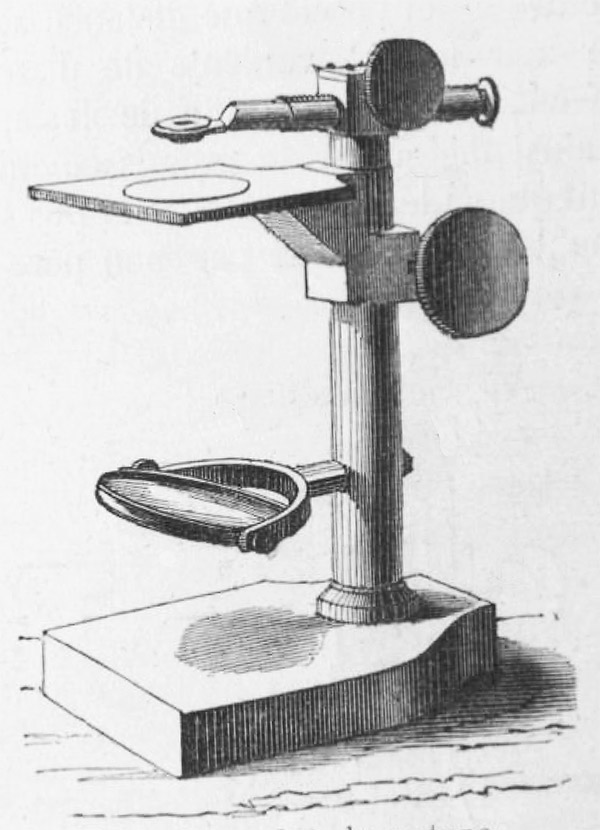

Figure 1.

Signed “V. Chevalier aîné, opticien, quai de l’Horloge-du-Palais, 69”. The compound body resembles the style of Louis Dellebarre (1726-1805). It stands a massive 30 inches / 80 cm tall. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an auction brochure.

Figure 2.

A. A circa 1824 “Selligue”-type microscope, signed “Selon Mr Selligue par Vincent Chevalier aîné, Ingr. Opten. Breveté, Quai de l'Horloge No 69 à Paris”. Image adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from “Museum of Art and History, Geneva”, by Margarida Archinard.

B. A second “Selligue”-type microscope, also signed by Vincent Chevalier. This example was later modified, and the optics are not original. Adapted by permission of Jeroen Meeusen from https://www.meeusen.com.

C. Diagram of cross-sections of the achromatic microscopes of Chevalier (left) and Selligue (right), showing the different number of lenses used in each objective. From “Bulletin de la Société d'Encouragement pour l'Industrie Nationale”, 1825.

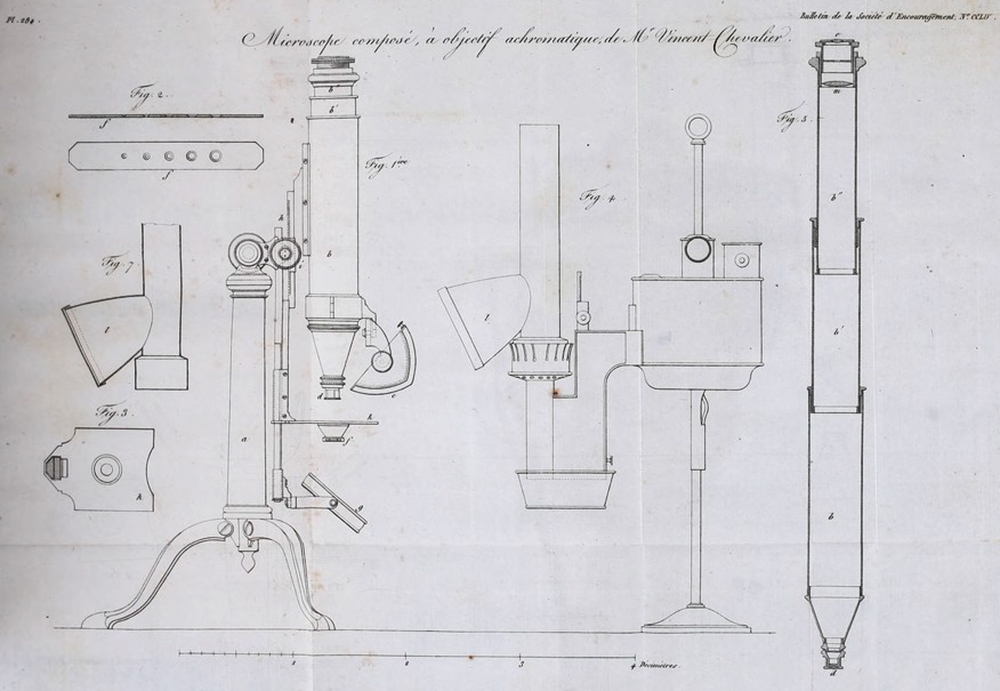

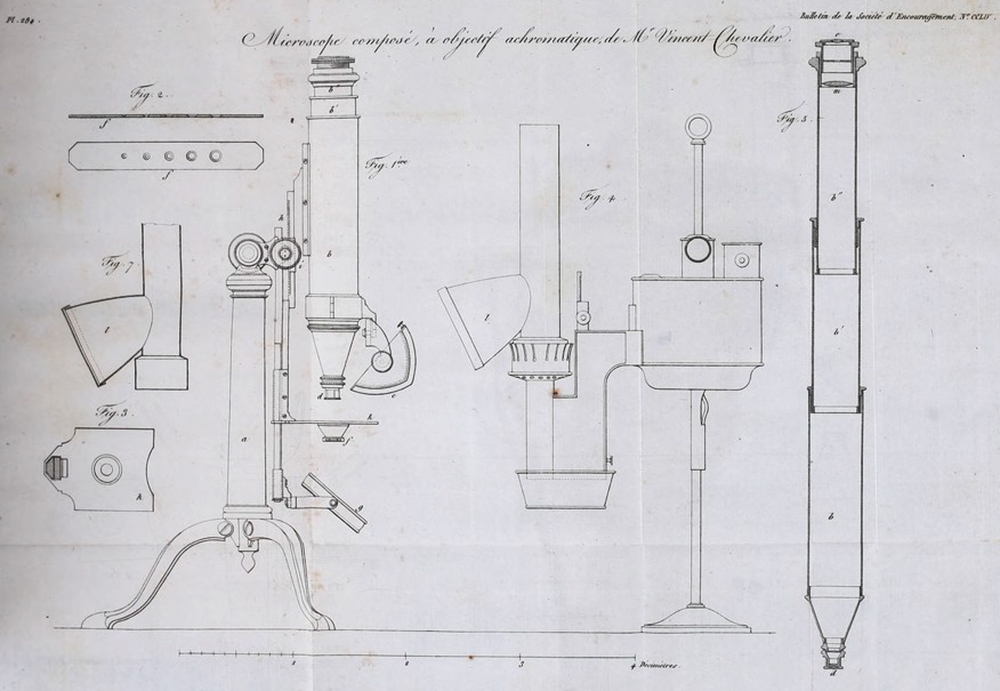

Figure 3.

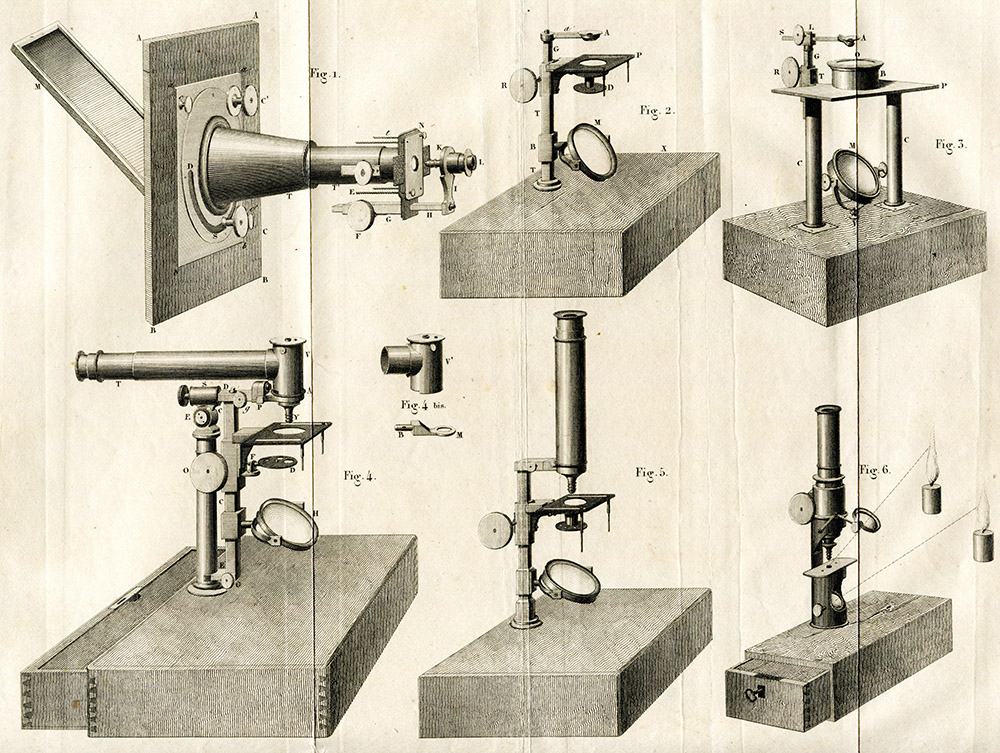

Illustration from “Microscope Achromatic, Selon Euler, Construit et Perfectionné de 1825 a 1826, par Vincent Chevalier ainé et fils”. It was adapted by the Chevaliers from the figure that accompanied an 1825 article that was published in “Bulletin de la Société d'Encouragement pour l'Industrie Nationale”, which compared the Chevalier’s microscope with that of Sellingue, their erstwhile collaborator turned competitor. In the “Bulletin”, this figure is captioned: “Fig. 1. The microscope of M. Chevalier, seen in side elevation and in experiment. a, microscope stand; b, body of the telescope; b', first draw; b", second draw; c, eyepiece; d, achromatic objective; e, prism with curvilinear surfaces, through which light is projected onto opaque bodies; f, variable diaphragm with decreasing holes, to moderate the effect of reflection of the mirror; g, mirror which reflects the light for transparent objects; h, rack adapted to the body of the telescope and in which meshes a pinion mounted on the axis of a screw, i, it is used to move the stage, k, up or down. Fig. 2. Sliding diaphragm with graduated apertures, seen in side and top views. Fig. 3. Stage on which objects are placed. Fig. 4. Lamp with double air current, the light of which projects through the prism to illuminate objects. l, parabolic reflector of this lamp. Fig. 5. Section of the telescope of the microscope of Mr. Chevalier, - b, body of the telescope; b', first draw; b", second print; c', first biconvex eyepiece; c", second bi-convex eyepiece; d, achromatic objective composed of three glasses of 6 lines (14 mm) of focus. Fig. 7. Section of the lamp chimney and the parabolic reflector”. (Figure 6 was omitted in the Chevalier reprint, as it is an illustration of Sellingue’s design - compare with Figure 2C, above).

Figure 4.

An example of the initial, 1825 form of the Chevalier’s Euler-type microscope. Signed “Selon Euler perfectionné par Vincent Chevalier Ingr. Ainé Opten. Quai de l'Horloge No 69 à Paris”. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from R.H. Nuttall, "Microscopes of the Frank Collection, 1800-1860". The author suggested that this microscope may have been produced after Charles left the partnership in 1830.

________________________________________________________________________

Vincent and Charles Chevalier, “aîné et fils”, 1826 - 1833

Probably due to Charles’ insistence for recognition of his contributions to the achromatic microscope, the business began to be known as “Chevalier ainé et fils”, or variants thereof.

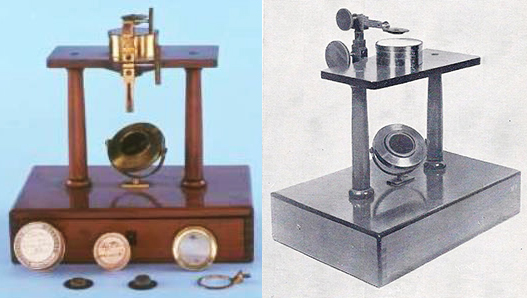

Figure 5.

Two examples of “microscope achromatique selon Euler”, both signed by Vincent and Charles Chevalier. The foot, arm, and substage are distinct from their initial, 1825 design (see Figure 4), implying that these are later productions, from the late 1820s. Images adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from http://www.mhs.ox.ac.uk/collections/imu-search-page/record-details/?TitInventoryNo=51388 and an internet auction site.

Figure 6.

A later form of achromatic microscope, signed “Perfectionné Vinct. Chevalier ainé et fils, Ingrs. Optns. Brevetés, Quai de l'Horloge No 69 à Paris”. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from Brian Bracegirdle “Science Museum, London”.

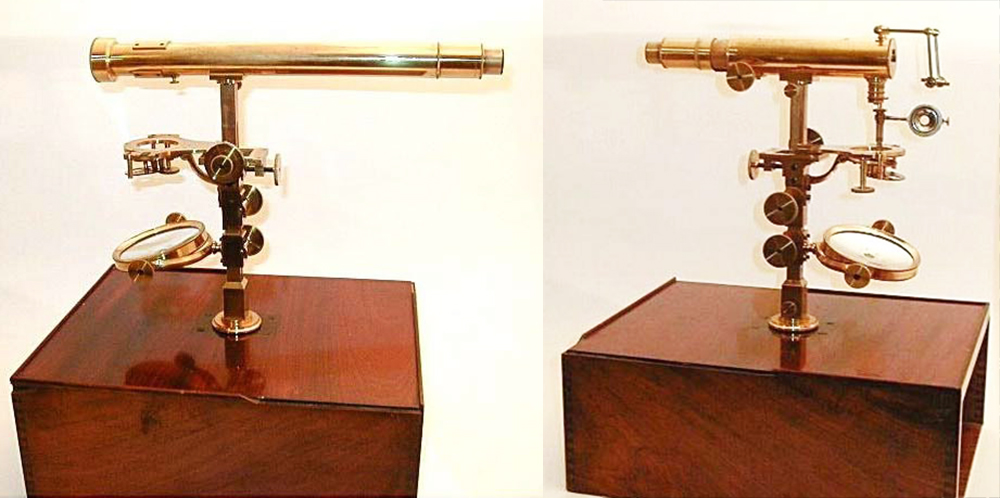

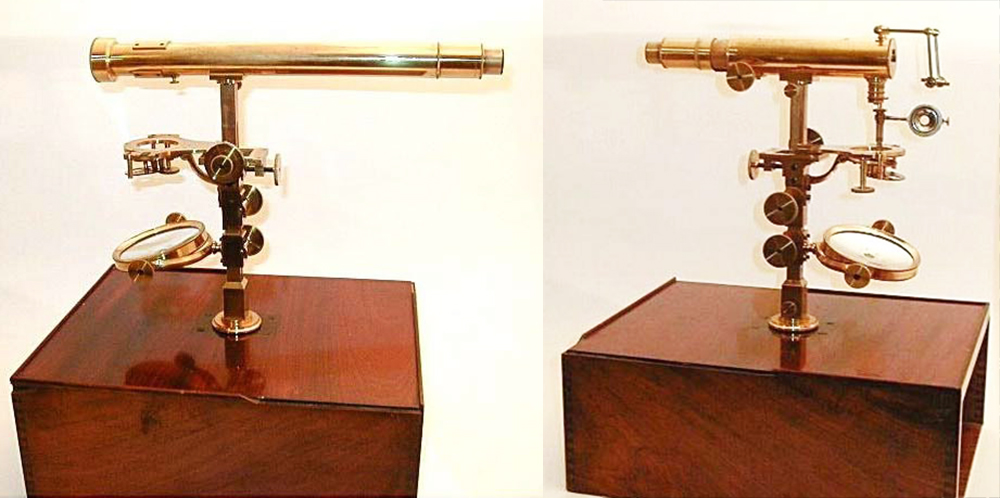

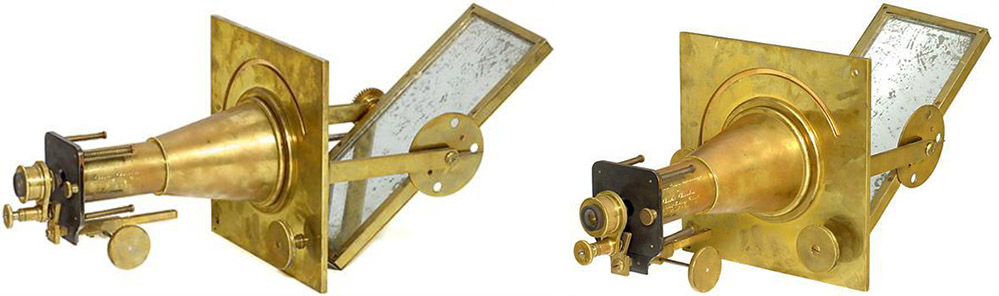

Figure 7.

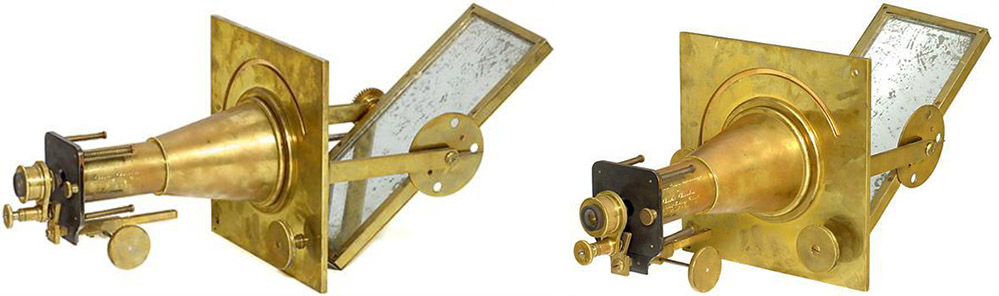

A horizontal microscope by Vincent & Charles Chevalier, with two, interchangeable body tubes. The left image shows the "catadioptric" reflecting body tube: a small mirror is directly above the specimen, set at a 45 degree angle, which reflects light toward the short end of the body tube, where a concave mirror magnifies and reflects the light path down the length of the body tube to the ocular lens. Magnification is achieved by reflection of the lightpath by parabolic mirror, in principle, like a reflecting telescope. Although the catadioptric reflecting method achieves magnification without spherical or chromatic aberration, it was very difficult to produce small, uniformly smooth mirrors. The right image shows the "dioptric" compound body in use: light from the specimen passes through an achromatic objective lens, then is redirected by a glass prism toward the ocular lens. The catadioptric body tube is signed "Vincent Chevalier aîné et C.L. Chevalier Opticiens Brevetés à Paris, 1828", and the compound body tube is signed "Vincent et C. Chevalier Optns Brevetés Quai de l'Horloge No 69 à Paris, 1829". Adapted by permission from http://www.kambeck.de/index.php/mikroskope-microskopes/2-uncategorised/109-m100.

________________________________________________________________________

Vincent Chevalier, “aîné”, 1833 - 1841

Charles left the partnership to establish his own business in 1833. Vincent continued at 69 Quai de l’Horloge until his death on November 29, 1841. He was often referred to as “aîné” (“elder”), to clarify his position with Charles and brother Louis. The following microscopes are signed by Vincent alone, and the designs suggest that they were probably produced after the split with Charles.

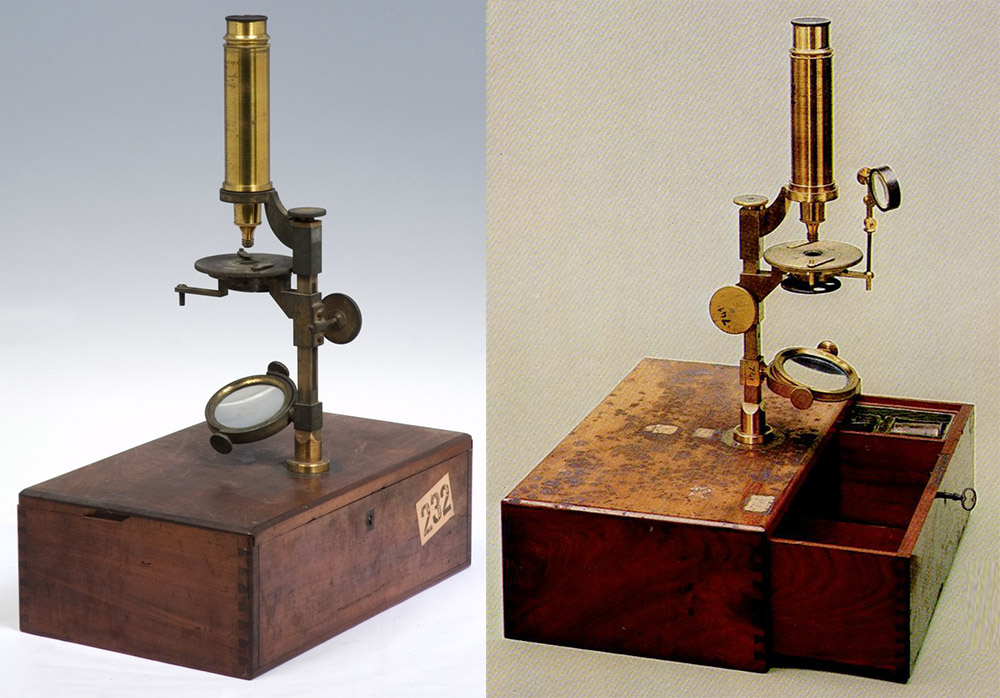

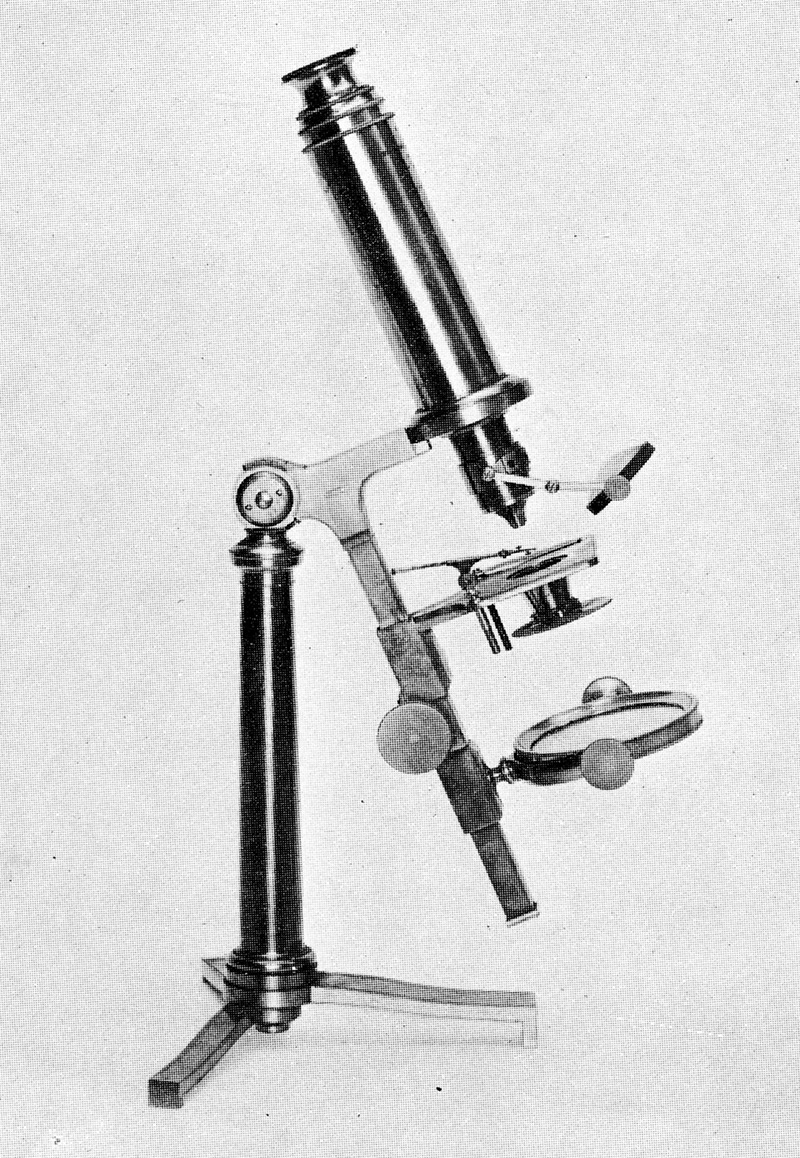

Figure 8.

A Euler-type microscope, signed “Vincent Chevalier, Achromatique Perfectionne, Ingr Brevte, Quai de l'Horloge 69, Paris”. It is very similar to the microscopes shown in Figure 5, above. Note, however, that the condenser for viewing opaque specimens, initially a thick prism, is now a biconvex “bull’s-eye” lens. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from “The Catalogue of the Billings Microscope Collection”, Fig. 55, page 29.

Figure 9.

A case-mounted compound microscope, for use as either a compound of simple instrument, signed “Microscope Achromatic, par Vincent Chevalier, Ing Brevéte, Quai de l’Horloge 69, Paris”. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet sale site.

Figure 10.

Signed “Microscope Achromatic Perfectionne, Vincent Chevalier, Optn Brevte, Quai de l’Horloge 69, Paris”. The arm and the placement on the wooden case are different from the microscope shown in Figure 9. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet sale site.

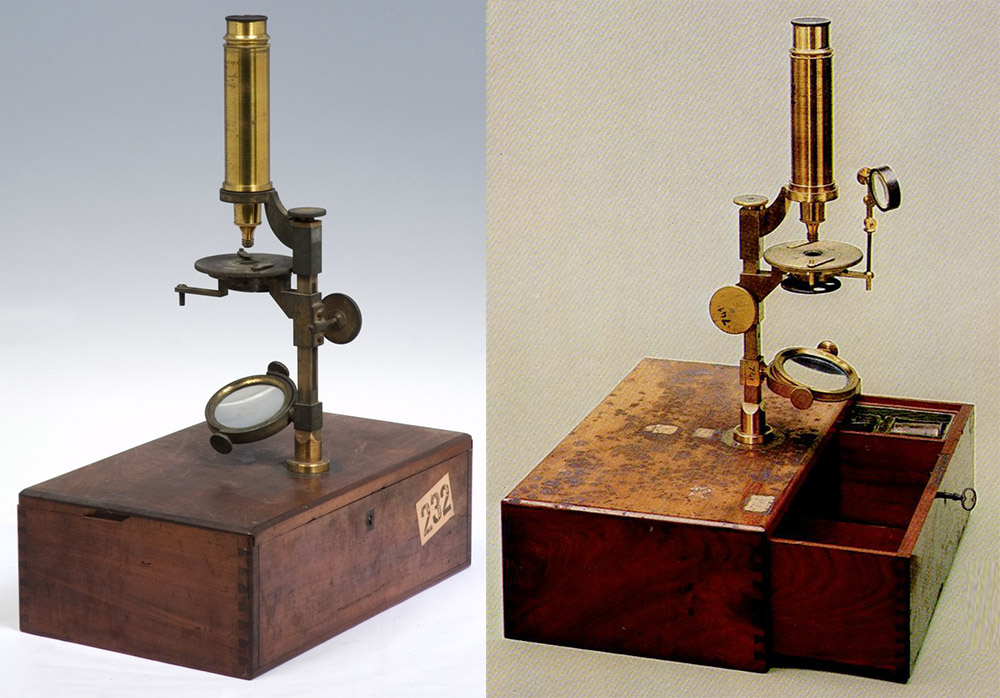

Figure 11.

Two additional case-mounted achromatic microscopes by Vincent Chevalier. Adapted for nonprifit, educational purposes from http://www.mhs.ox.ac.uk/collections/imu-search-page/record-details/?TitInventoryNo=39889 and http://jedlik.phy.bme.hu/~hartlein/Museum/Museum-old/Optics-6.html.

Figure 12.

A tripod-mounted achromatic microscope by Vincent Chevalier. Above the foot, the design closely resembles the case-mounted microscopes that are shown in Figures 9-11. Shown with a horizontal body tube attached. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co8159/microscope-by-vincent-chevalier-microscope.

Figure 13.

A solar microscope by Vincent Chevalier. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet sale site.

Figure 13B.

ca. 1827 sunglasses, with a label that names only Vincent Chevalier. The label highlights the Silver Medal that was awarded to Vincent and Charles at the 1827 Exposition des Produits de l’Industrie. The father and son partnership won another Silver Medal in 1828. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet sale site.

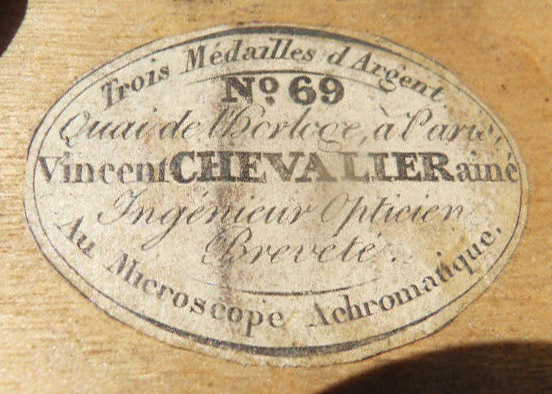

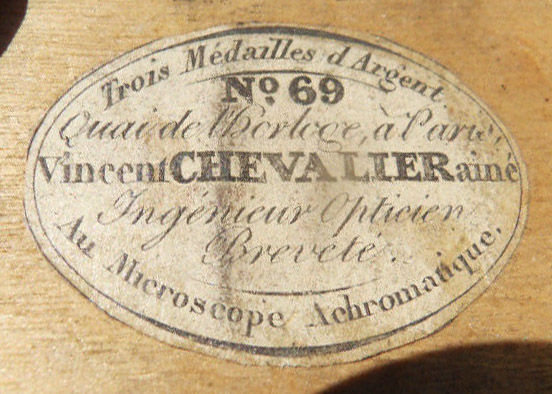

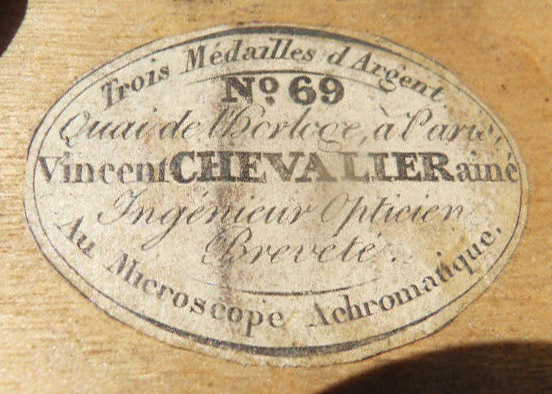

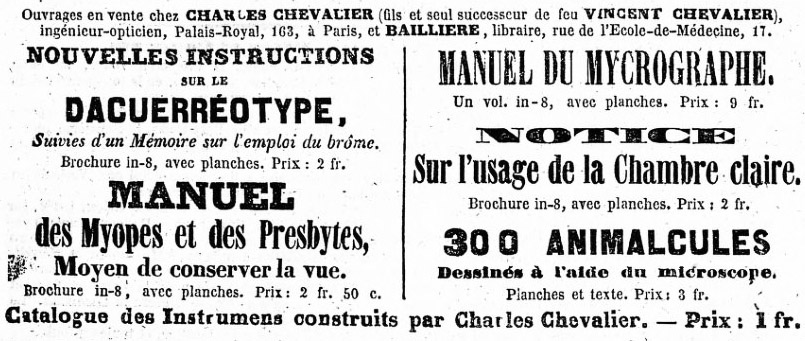

Figure 13C.

A Vincent Chevalier trade label, from the case of a ca. 1833 Raspail-type microscope. The label mentions three Silver Medals; Vincent and Charles won such medals in 1827, 1828, and 1830. After the partnership ended, Vincent won a Silver Medal in 1834, while Charles won a Gold Medal at the same exposition. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet sale site.

________________________________________________________________________

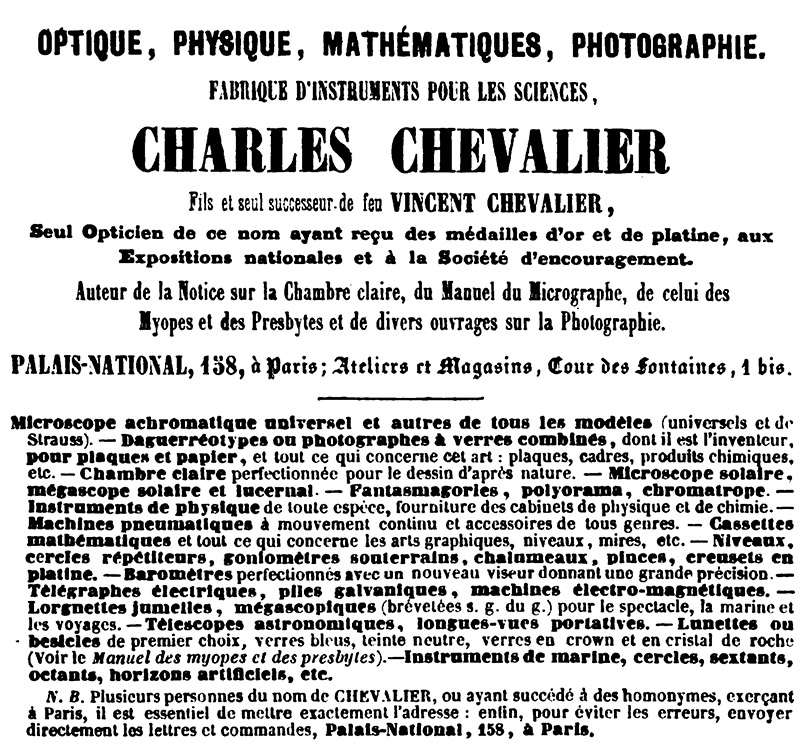

Charles Chevalier, 1833 - 1859

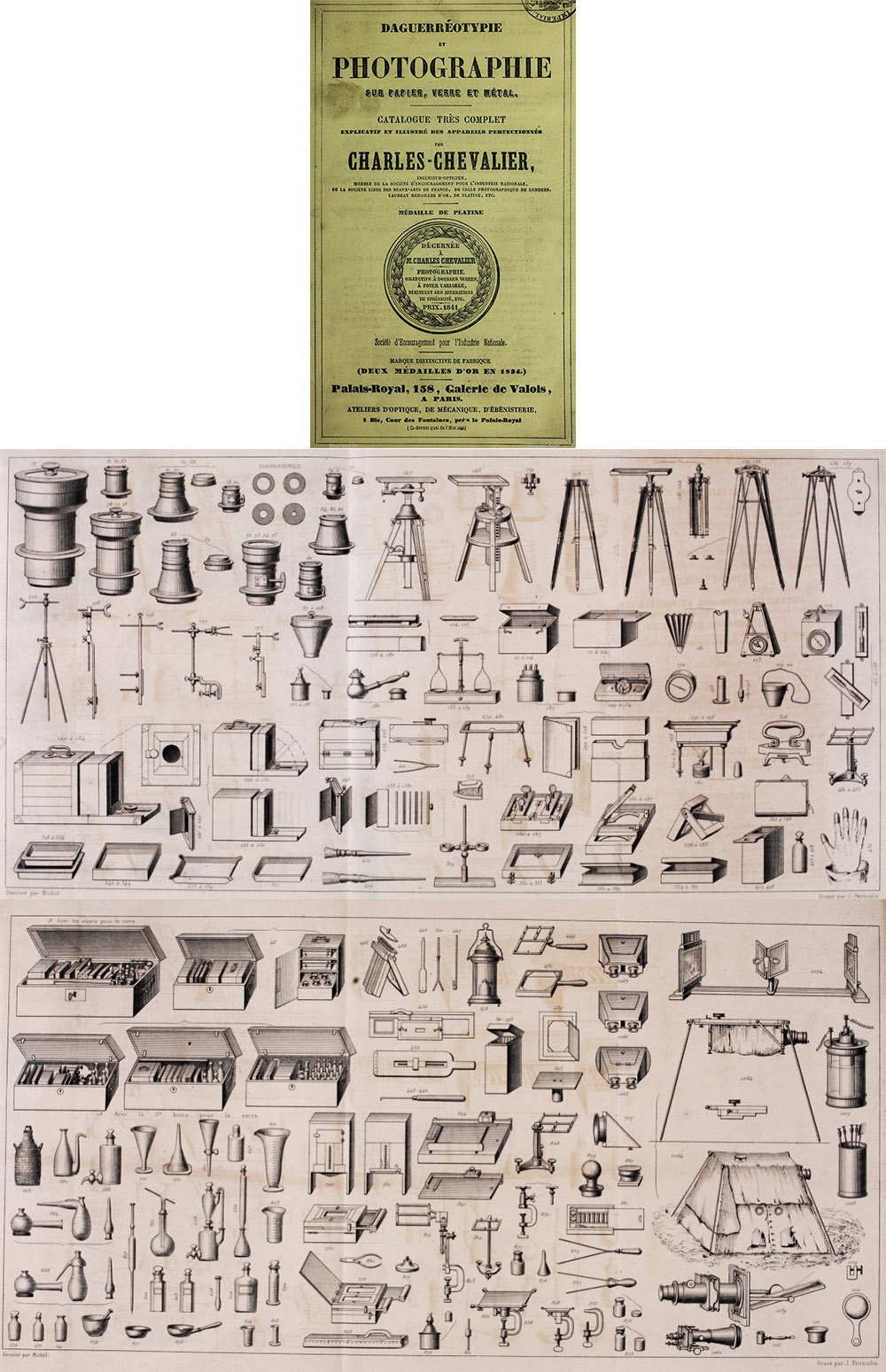

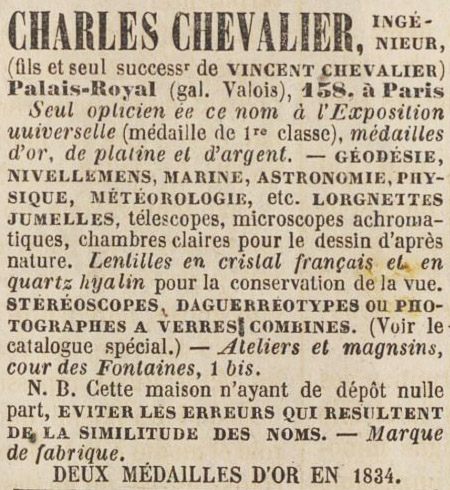

Charles left his father’s house and business in 1833, and established a separate business at 163 Palais Royal. He occasionally stated that this shop was on Galerie de Valois within the Palace. Palais Royal became Palais National in 1848. Charles’ business address changed from number 163 to 158 in 1849. The building’s name reverted to Palais Royal in 1852. Those address changes permit approximate dating of Charles Chevalier’s products.

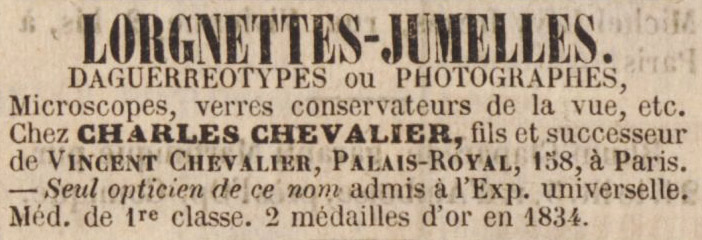

Charles published the book Des Microscopes et de Leur Usage in 1839, which included detailed engravings of 7 different models of his microscopes, printed on fold-out sheets. Both of those plates of illustrations are shown below in Figures 19-20. Charles made two different versions of his “Achromatique Universel” (“Universal Achromatic”) microscope, which differed substantially in their sizes and mode of mounting the body to the upright support - examples of each are shown in Figures 21-22. Surviving examples of the other models illustrated in Des Microscopes are shown in Figures 17 and 23-26.

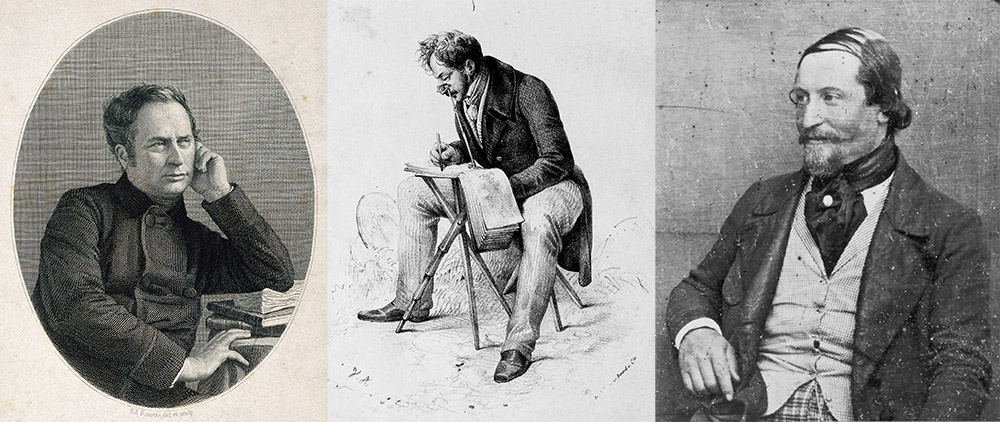

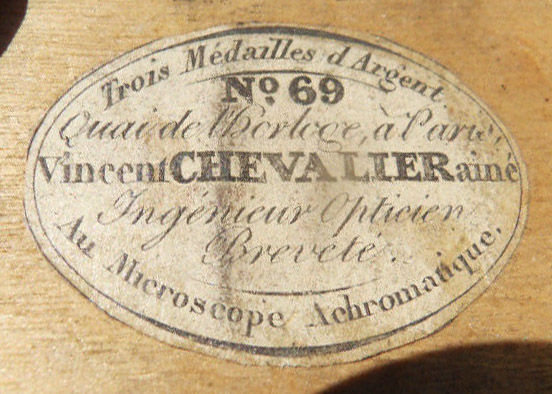

Figure 14.

Portraits of Charles Chevalier. Left, undated lithograph, from “Le Etudiante Micrographe”, 1865, second edition. Center, lithograph from his “Chambre Claire”, 1838. Right, photographic self-portrait, ca. 1843.

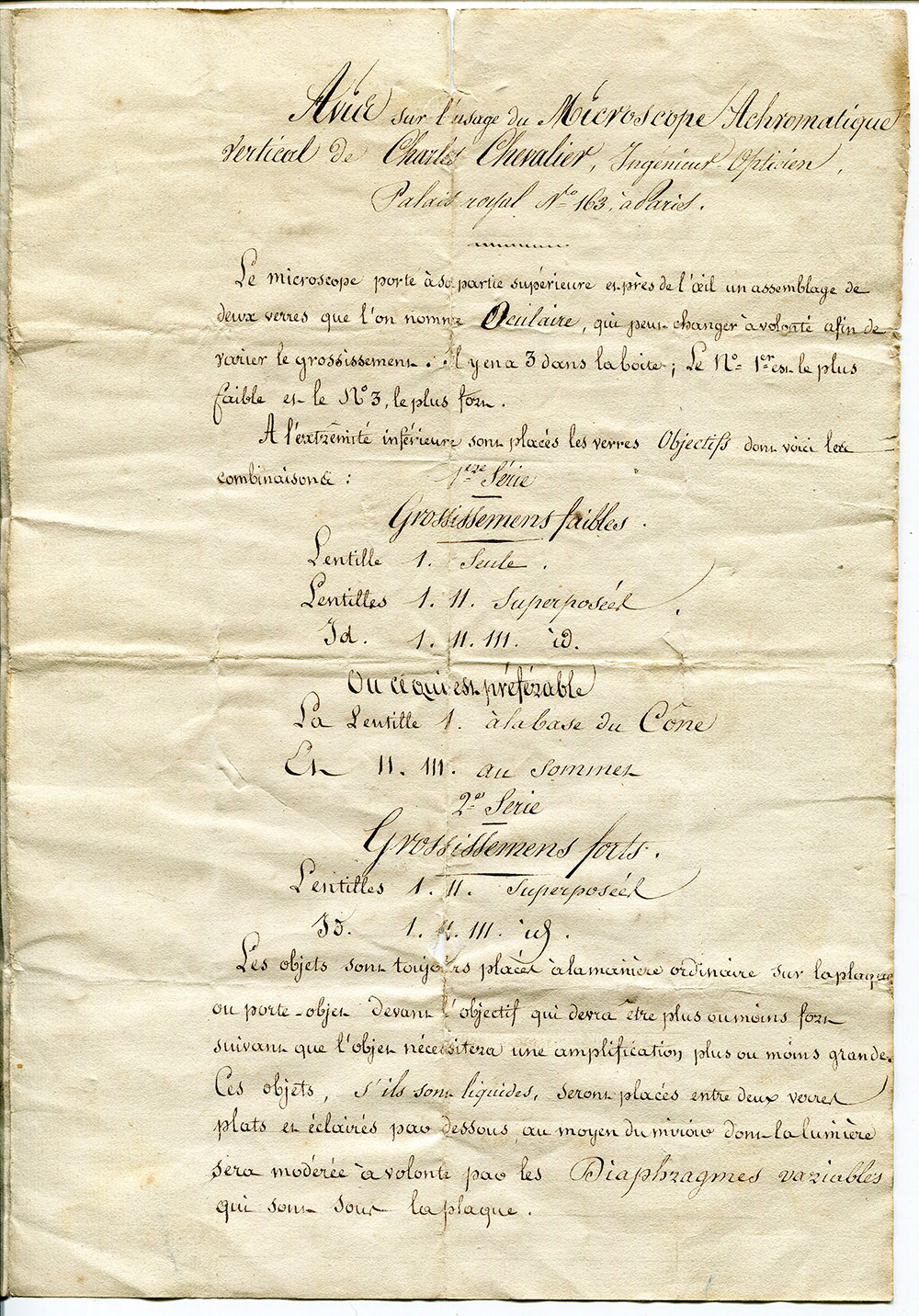

Figure 15A.

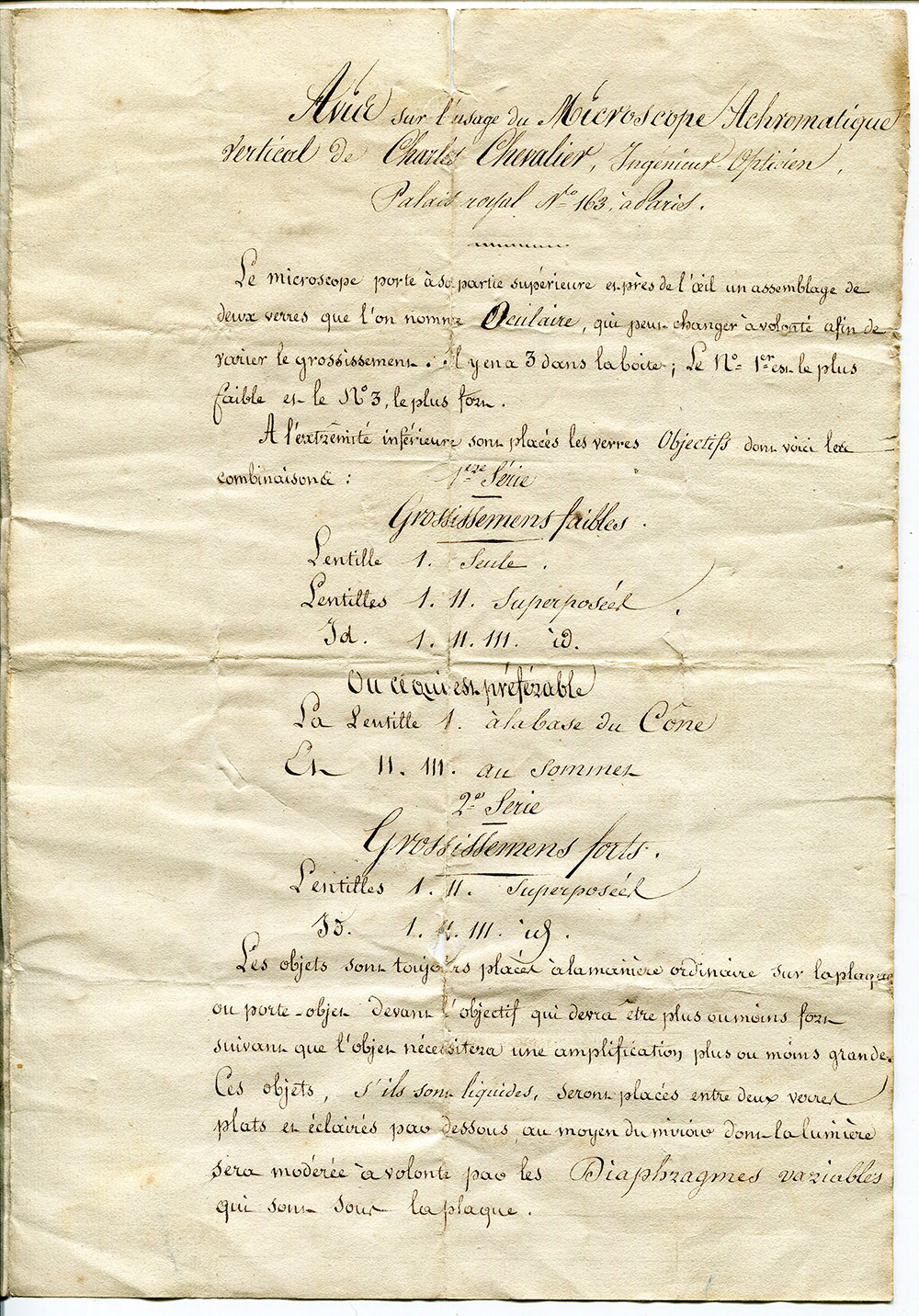

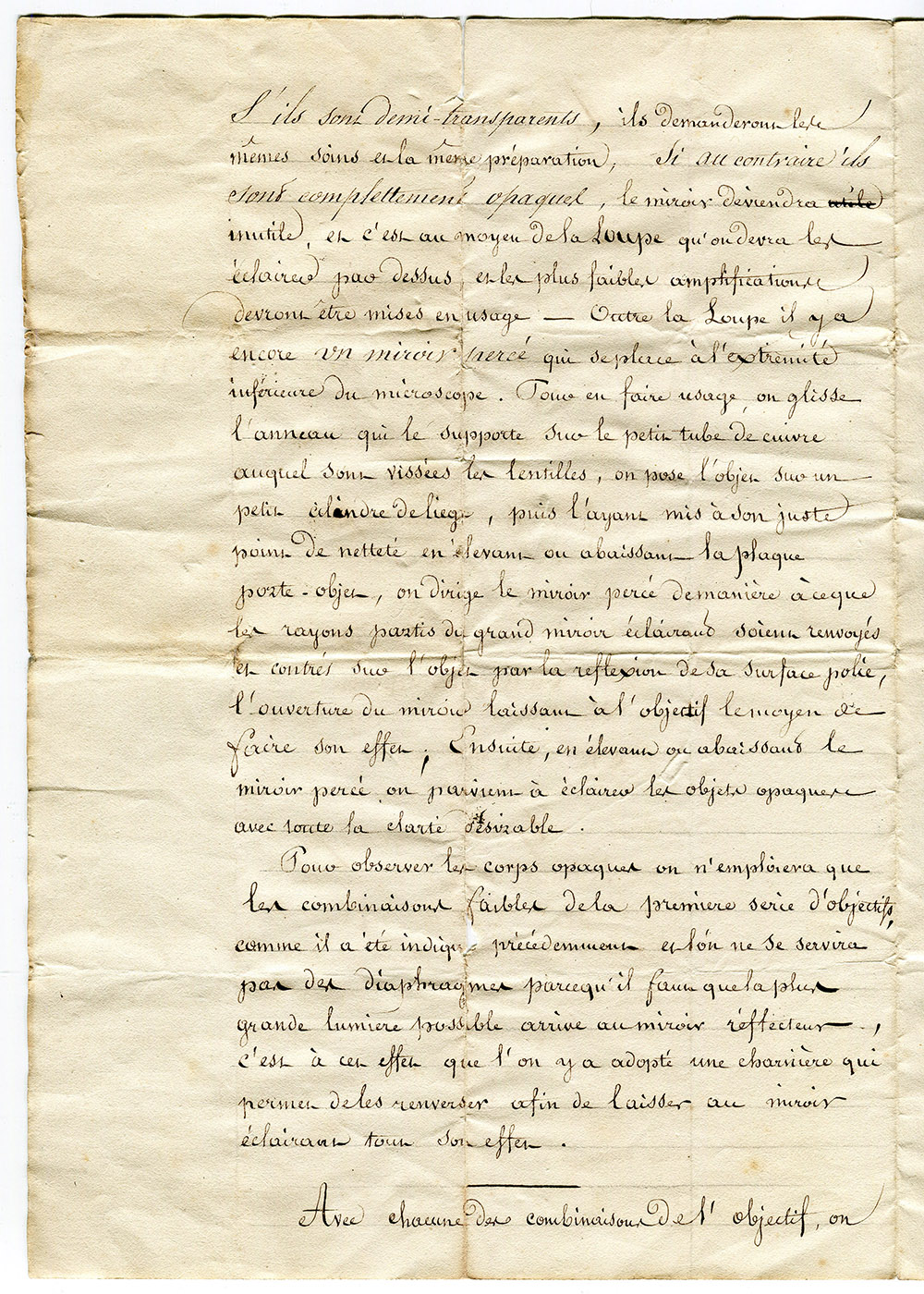

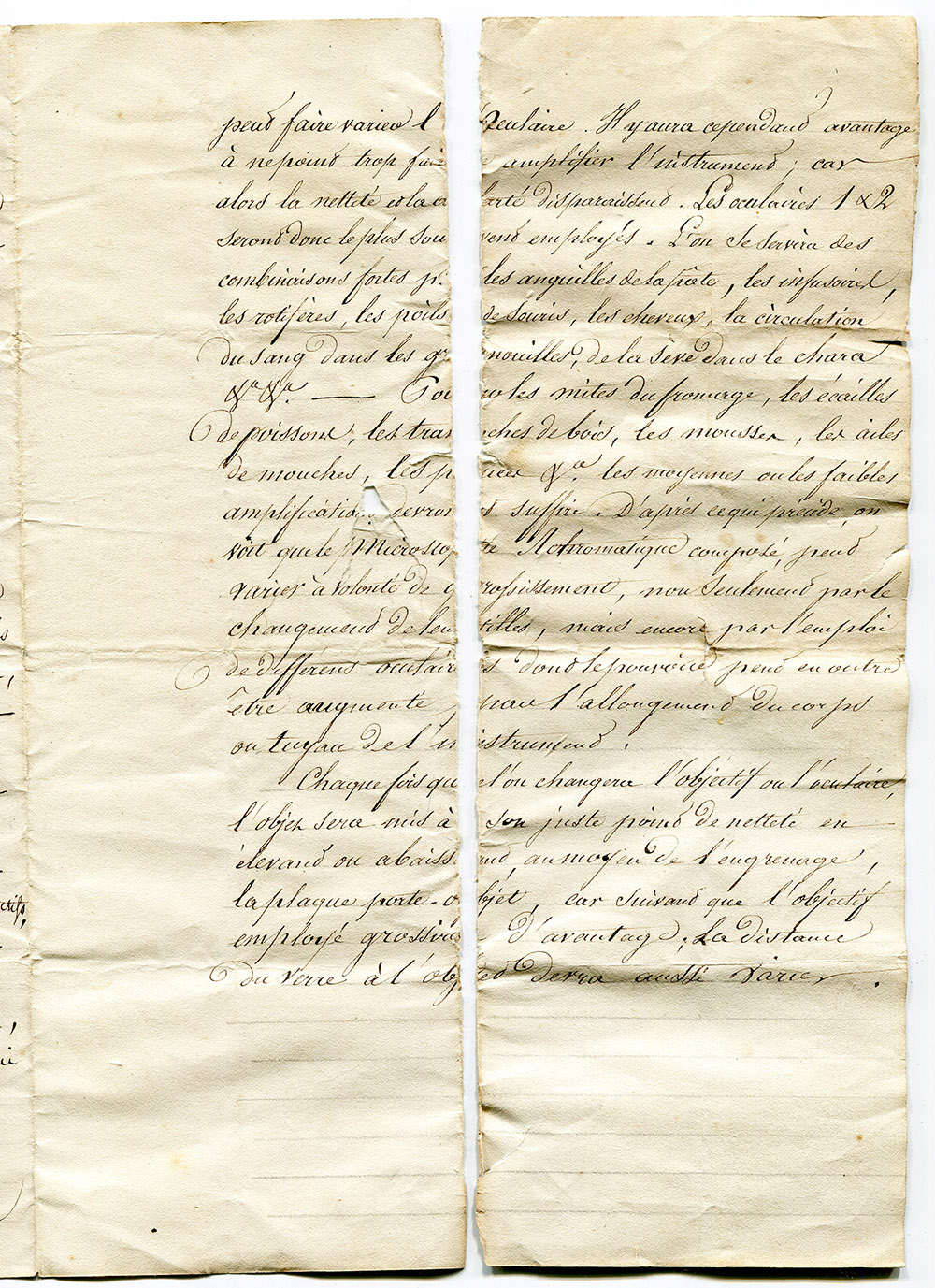

A Euler-type microscope, signed "Microscope Achromatique, Perfectionné, par Charles Chevalier, Ingr Optn, Palais-Royal 163, à Paris". This model was not shown by Charles in his 1839 "Des Microscopes", and so had probably been discontinued by the mid-1830s. The original paperwork that accompanied this instrument is shown below as Figure 15B.

Figure 15B.

Original paperwork that accompanied the Microscope Achromatique that is shown in Figure 15A (above).

Figure 16.

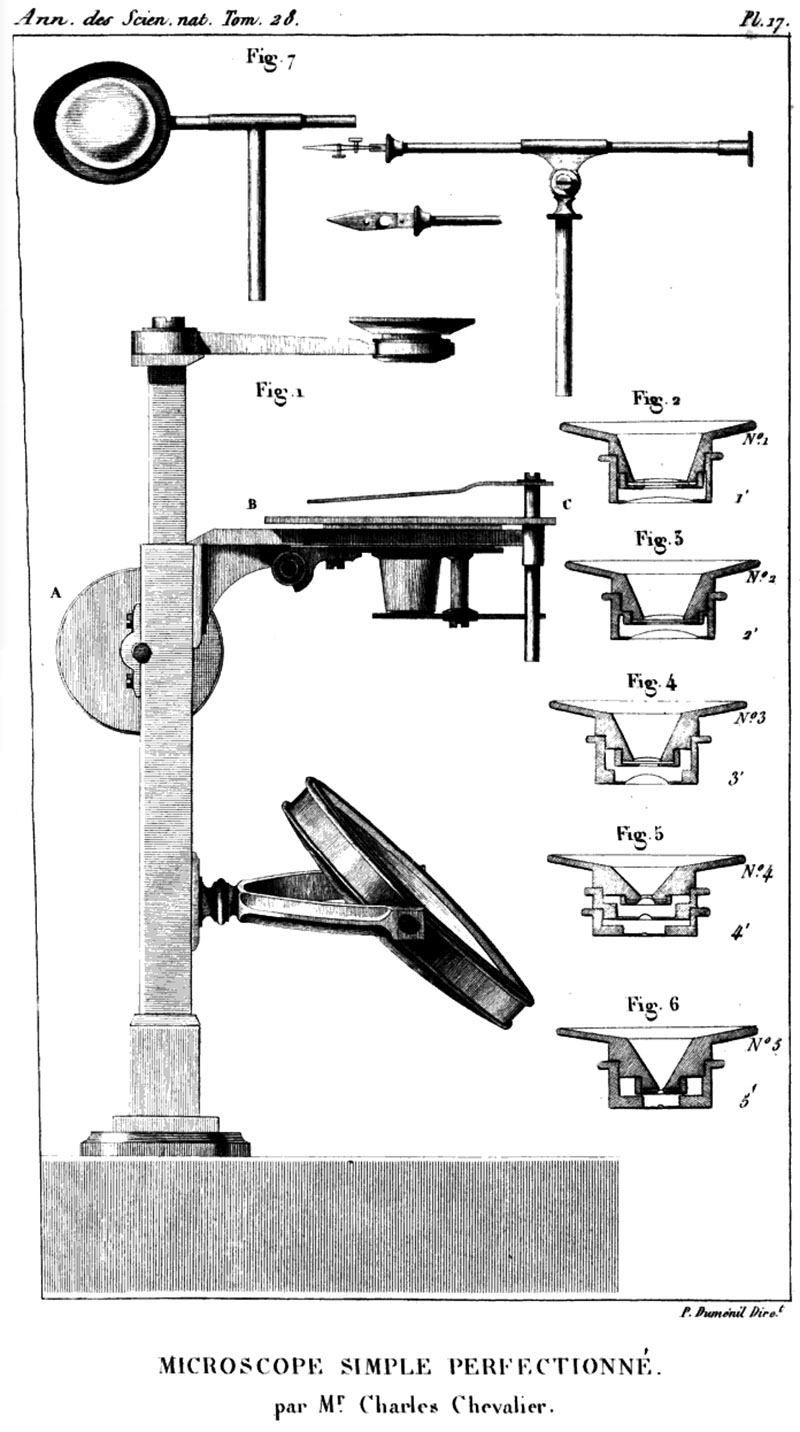

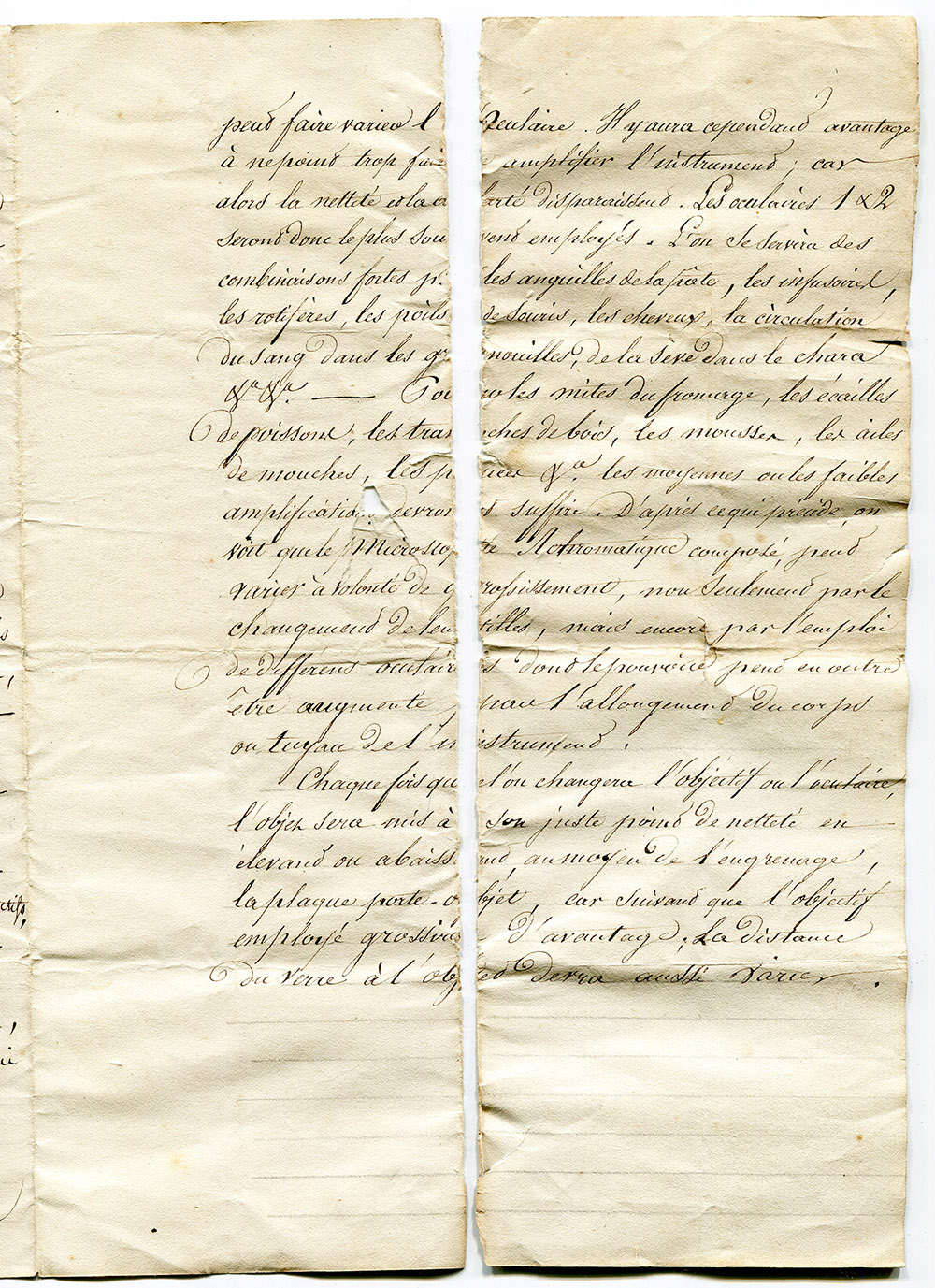

An 1833 diagram of Charles Chevalier’s "Microscope simple perfectioné", from his paper in "Annales des Sciences Naturelles". The instrument included doublet and triplet lenses. This model is also illustrated in Chevalier’s 1839 “Des Microscopes” (Figure 19).

Figure 17A.

A Charles Chevalier "Microscope simple perfectioné".

Figure 17B.

Presumably a later version of Charles’ "Microscope simple perfectioné", with a rack-and-pinion that adjusts the length of the arm. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://www.mhs.ox.ac.uk/collections/imu-search-page/record-details/?thumbnails=on&irn=11733&TitInventoryNo=15107.

Figure 18.

A case-mounted microscope by Charles Chevalier, with an adjustable arm and other features that resemble "Raspail"-type microscopes. The drawer has space for a compound body tube (now missing), indicating that this instrument was initially intended for use as a simple and compound microscope.

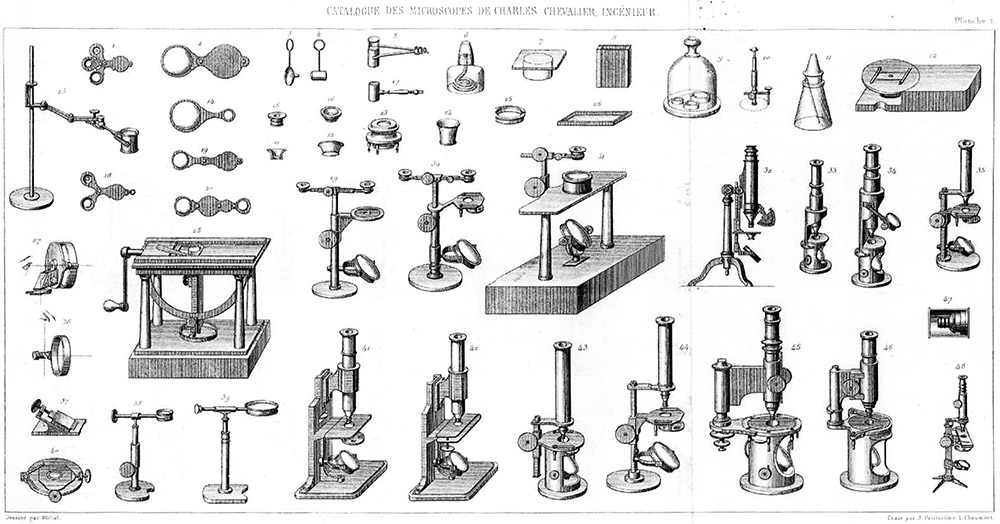

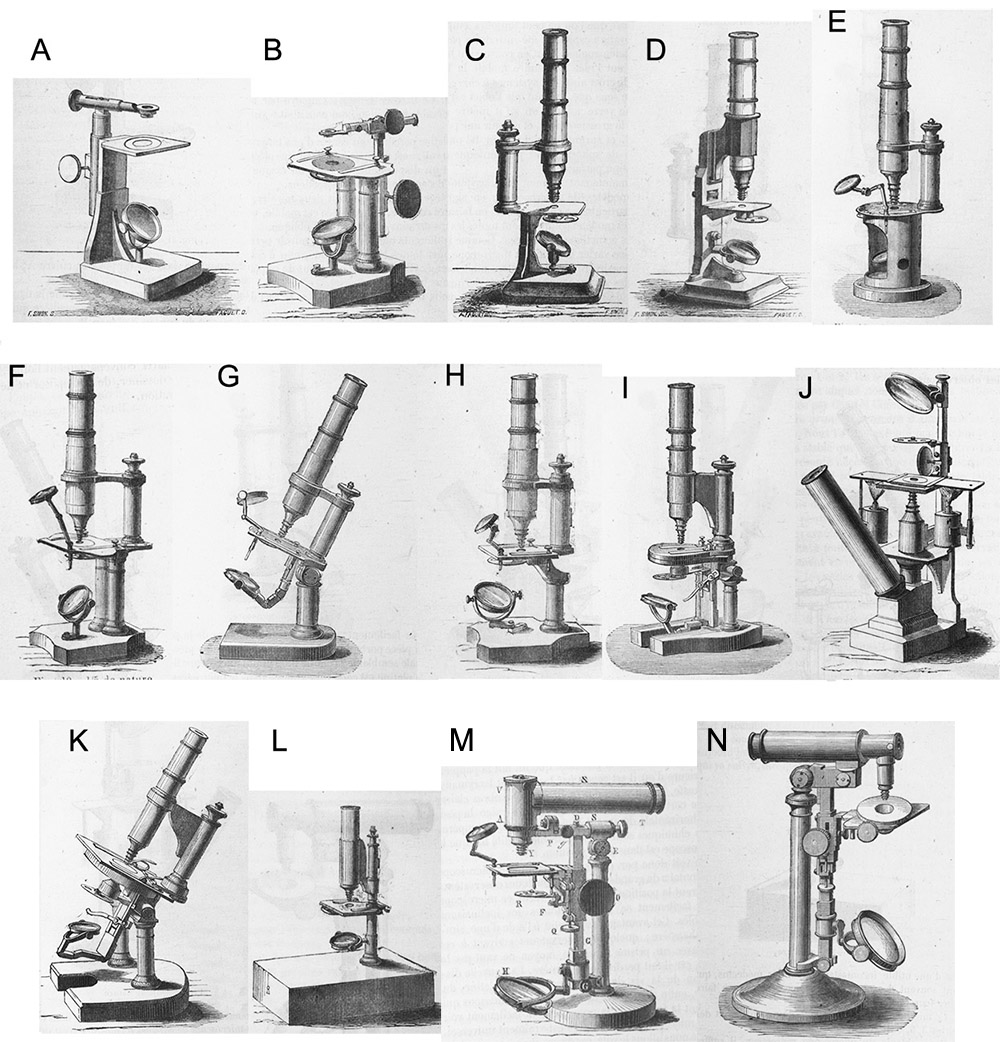

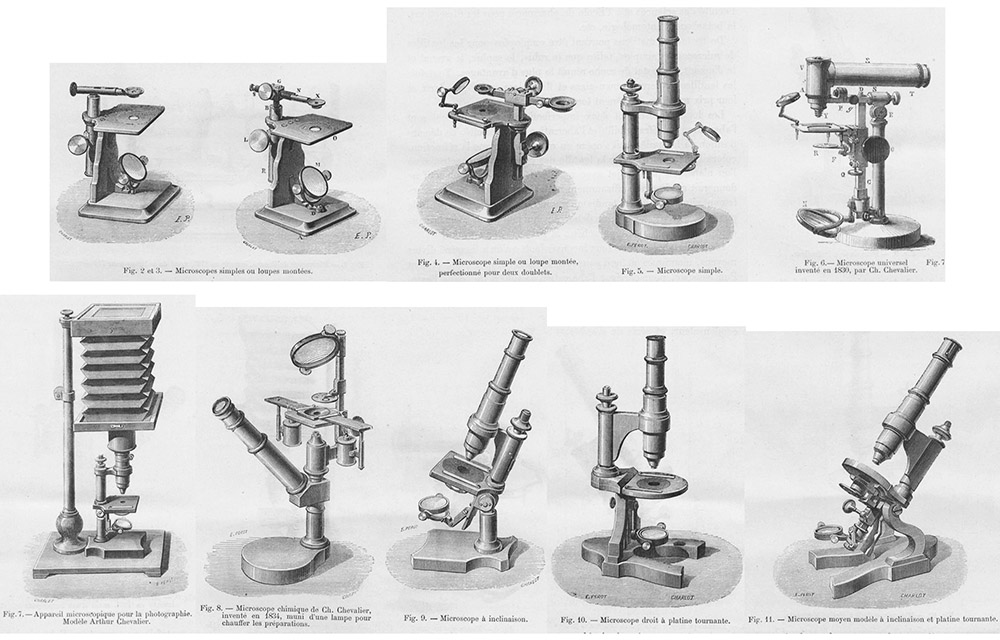

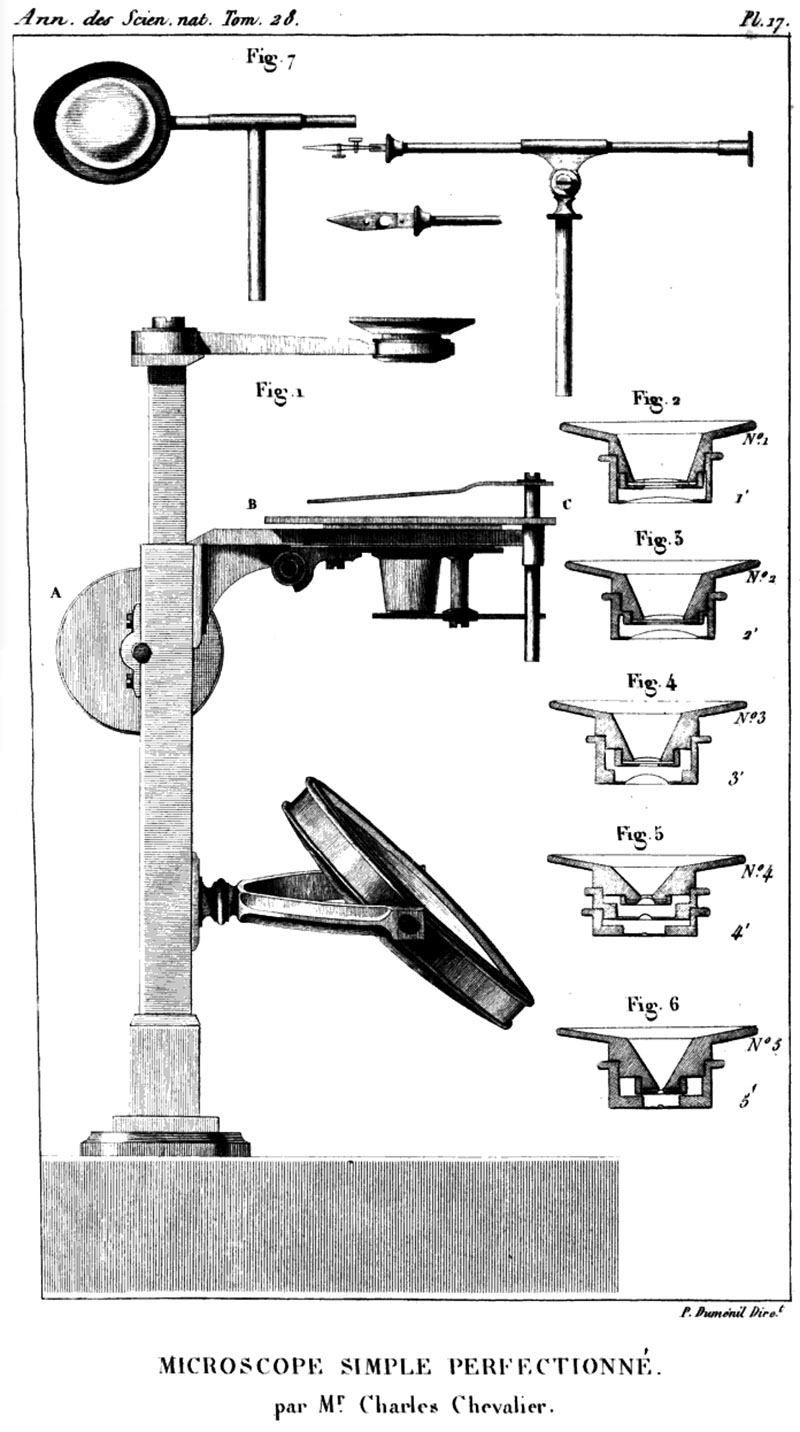

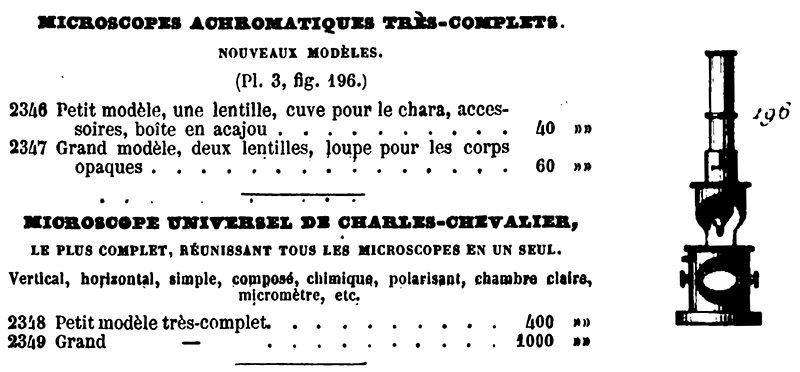

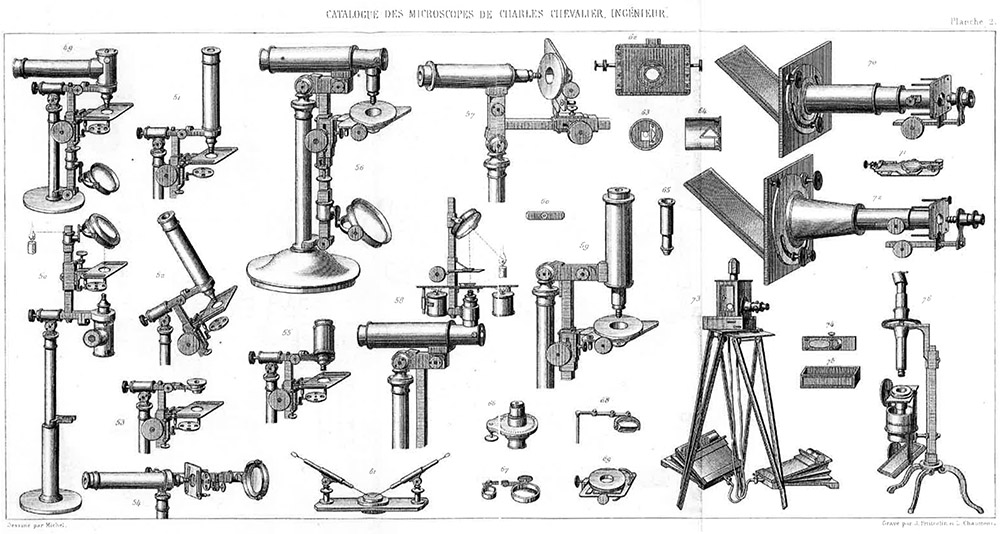

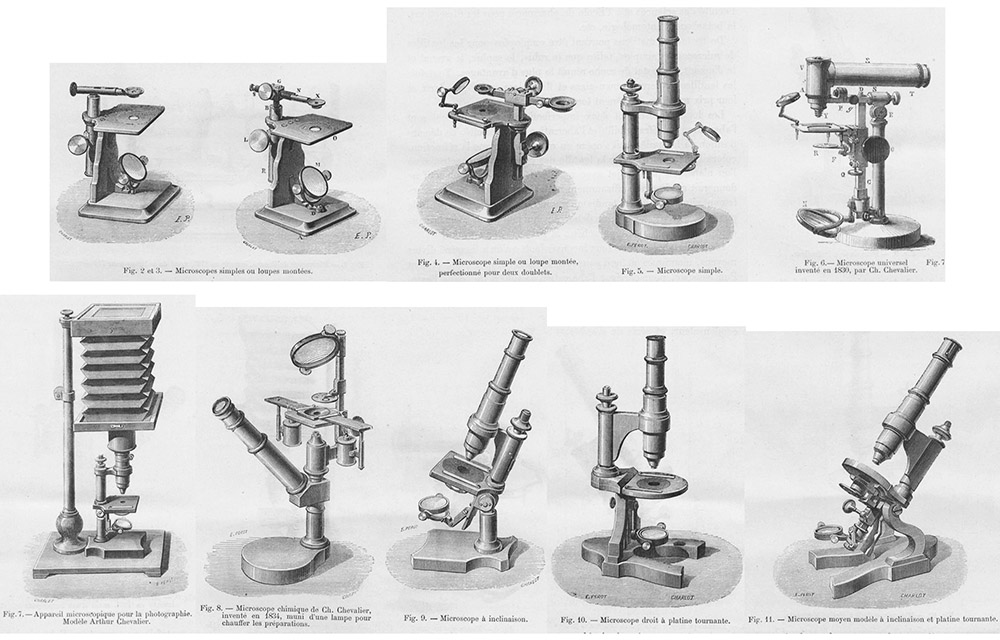

Figure 19.

Engravings of six 1839 Charles Chevalier microscope designs, from his “Des Microscopes et de Leur Usage”, Plate 3 (the overly-large sheet folds out from the book, hence the fold marks). The lower left image of this plate shows the small version of his “Achromatique Universel” (“Universal Achromatic”) microscope. Photographs of surviving instruments are shown in Figures 17, 21, and 23-26.

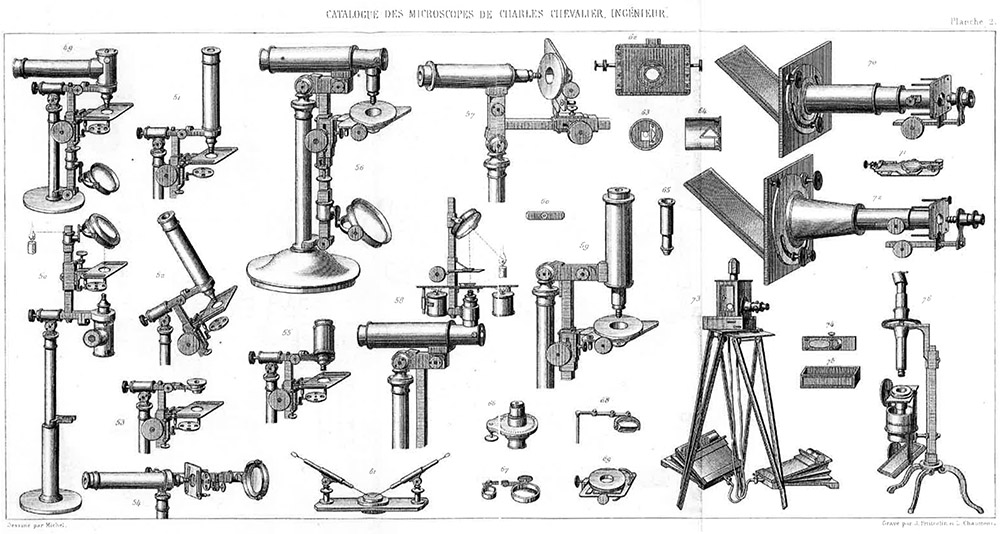

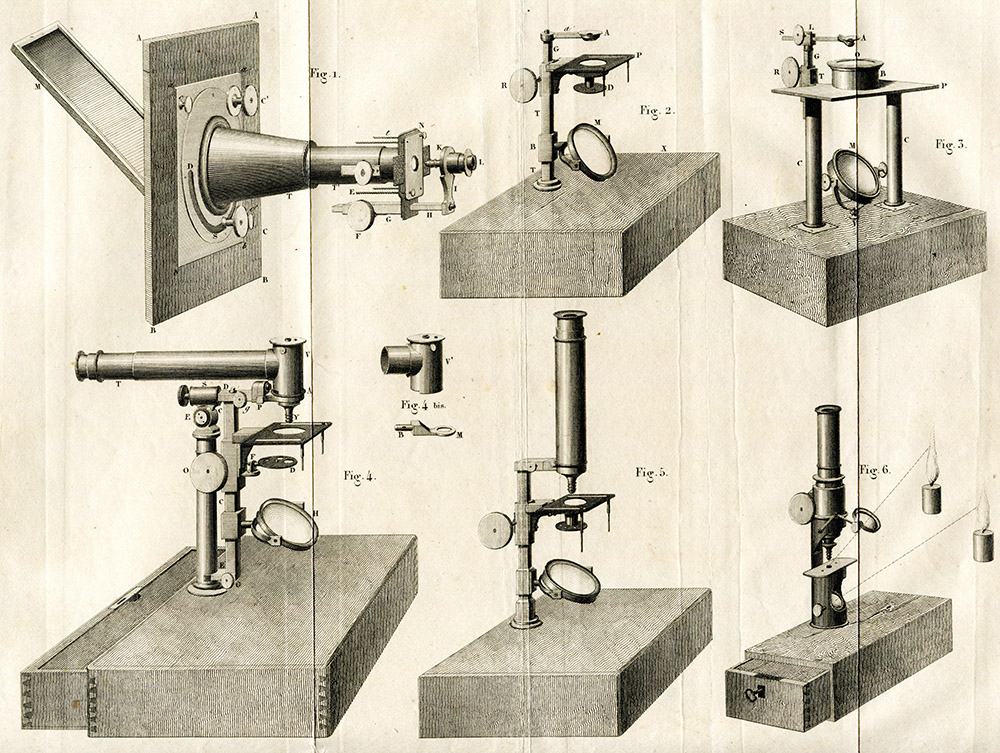

Figure 20.

Plate 4 from Charles Chevalier’s 1839 “Des Microscopes et de Leur Usage”, which shows details of the large form of the “Achromatique Universel”. This instrument is the only microscope that Chevalier described in depth, on pages 93-100, suggesting that it was a new product in 1839. The images in the upper right, labeled "Fig. 3" and "Fig. 3 bis", show the instrument set up as an inverted microscope for observation of chemical crystalization: "Fig. 3 bis" includes two small alcohol burners attached to the underside of the stage, which warm the stage to evaporate water from solutions and allow rapid observation of crystallization processes. In the lower right, "Fig. 8" shows the instrument set up as an Amician reflecting microscope. Examples of large “Achromatique Universel” microscopes are shown in Figure 22, below.

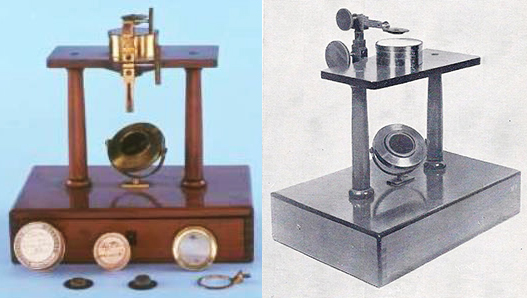

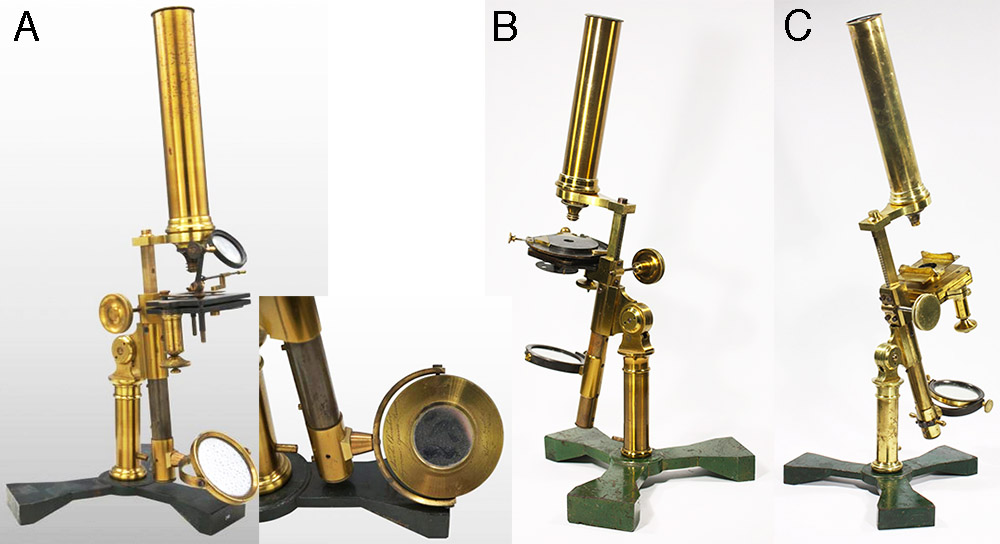

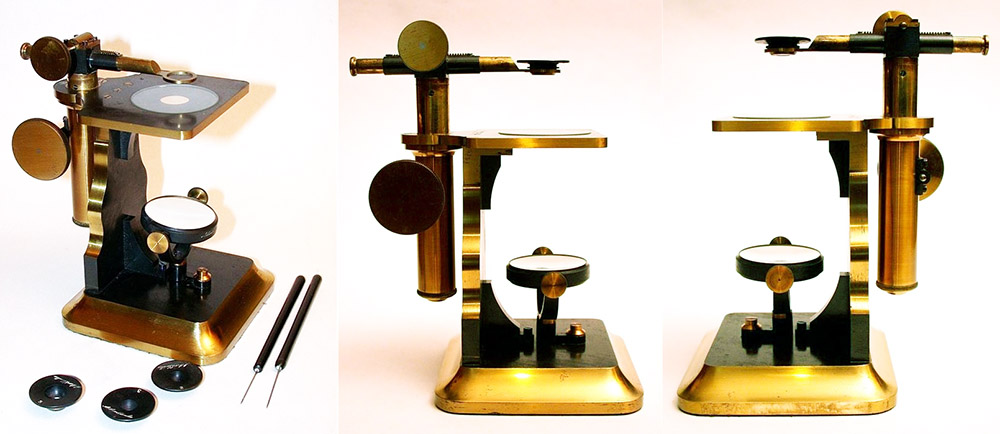

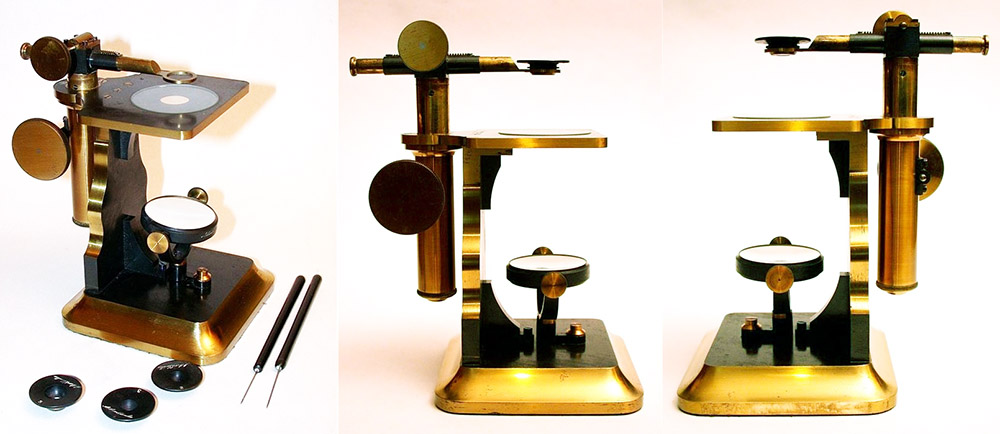

Figure 21.

Two examples of Charles Chevalier’s "Petit Modèle" of the “Achromatique Universel” (“Universal Achromatic”) microscope, as illustrated in plate 3 of “Des Microscopes” (see Figure 19, above). Charles’s son, Arthur, wrote that this model was invented in 1830, and won a Gold Medal for Charles at the 1834 Exposition des Produits de l’Industrie. The top example is mounted on a wooden cabinet, which contains a drawer for storing the microscope and accessories. The lower instrument is mounted on a heavy brass disc. The “Achromatique Universel” can be used as a horizontal compound microscope, a simple microscope, an inclinable compound microscope, or in inverted compound microscope (lower panel, left to right). The 90 degree tube addition for horizontal use has a prism in the bend, which reflects light to the eyepiece. Images adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://www.mhs.ox.ac.uk/collections/imu-search-page/record-details/?thumbnails=on&irn=6263&TitInventoryNo=35937 (top row), or by permission from http://www.microscope-antiques.com/chevhoriz.html (bottom row).

Figure 22.

Examples of the "Grand Modèle" of Charles Chevalier’s “Achromatique Universel” microscope, introduced in about 1839, and illustrated in plate 4 of “Des Microscopes” (see Figure 20, above). This is the only microscope that was extensively described by Chevalier in that book. This form is substantially larger that his earlier, first form, being roughly 50% larger in all dimensions. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from http://golubcollection.berkeley.edu/19th/167.html (left) and https://www.mhs.ox.ac.uk/collections/imu-search-page/record-details/?thumbnails=on&irn=5879&TitInventoryNo=38090 (right).

Figure 23.

A case-mounted compound / simple microscope, as illustrated in “Des Microscopes”, 1839. The arm is in two pieces, connected by a cylindrical rod, like that of the "Petit Modèle Achromatique Universel" (Figure 21). A pin with a round handle holds the two pieces firmly in place - removing the pin permits the body tube to revolve on the arm, for ease in changing the objective lens. The body is signed “Charles Chevalier, Ingénieur Opticien, Palais Royal, 163, Paris”. Images courtesy of Jeffrey Silverman.

Figure 23B.

This Charles Chevalier case-mounted compound / simple microscope is slightly different from the illustration in “Des Microscopes”, 1839: the arm is a solid bar, rather like that on his "Microscope simple perfectioné" (Figures 16, 17, and 19, above). The arm is signed “Charles Chevalier, Ingénieur Opticien Brevete, Palais Royal 163 Paris”. As with Chevalier’s other case-mounted microscopes, a slide-out drawer in the base holds accessories.

Figure 24.

Two views of a ca. 1839 Charles Chevalier dissecting microscope. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from http://mmb-web.adlibhosting.com/ais54/Details/collect/9561 and P. Van der Star’s "Descriptive Catalogue of the Simple Microscopes in the National Museum of the History of Science at Leyden", 1953.

Figure 25.

A drum-style compound microscope by Charles Chevalier, as described in 1839. A fellow Parisian, Georges Oberhaueser (1798-1868), made the drum microscope popular in the early 1830s, and this Chevalier model was probably a bid to catch that market. Image adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Figure 26.

A Charles Chevalier solar projection microscope, as described in his 1839 “Des Microscopes”. Adapted for nonprofit, educationa purposes from an internet auction site.

Figure 27.

Another, later solar projection microscope by Charles Chevalier. Adapted by permission from http://www.antique-microscopes.com/photos/Charles_Chevalier_solar_microscope.htm.

Figure 28.

A circa 1840s student-type microscope by Charles Chevalier. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co118171/student-microscope-by-charles-chevalier-paris-mi-student-microscopes.

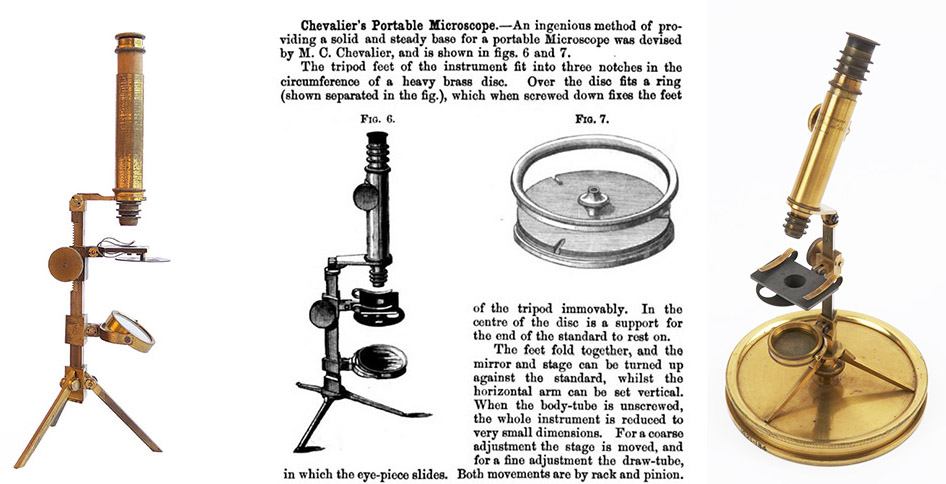

Figure 29.

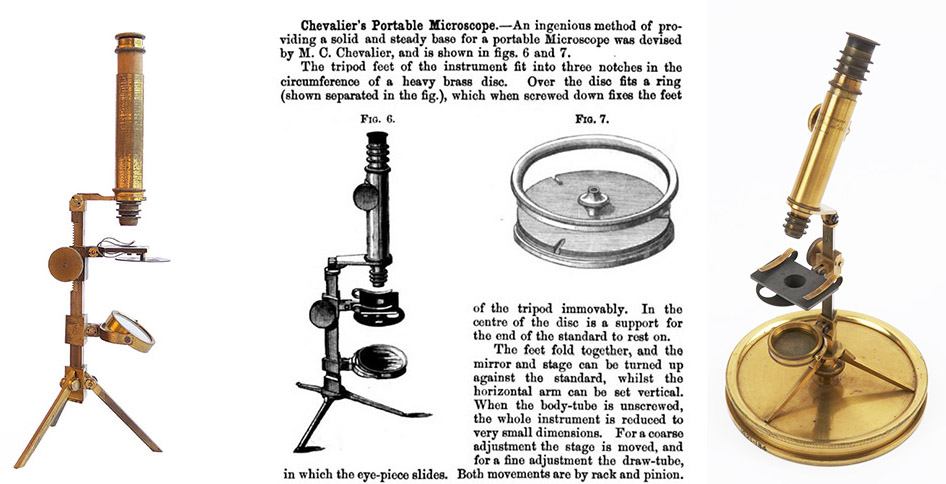

Charles Chevalier’s portable compound microscope, ca. 1840s. The microscope on the left is signed "Charles Chevalier, Palais Royal 163, Paris": Palais Royal became Palais National in 1848. The image is adapted with permission from https://www.meeusen.com. Shown on the center is an article from "The Journal of the Royal Microscopical Society", 1886, which noted that Chevalier provided a heavy brass base to secure the legs when in use. The microscope on the left is shown mounted in its circular base. Image adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co8158/portable-microscope-by-chevalier-portable-microscope.

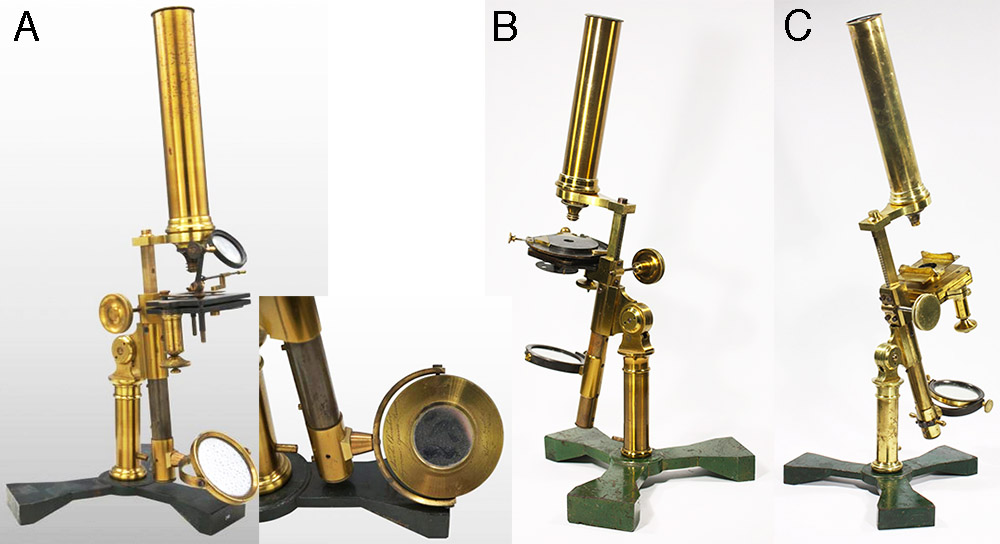

Figure 30.

Circa 1840s - 1850s microscopes. A is signed "Charles Chevalier, Ingeneur Opticien, Brevete, Palais Royale 163, a Paris", dating it to before 1848, while B and C are not signed. Another known example is signed on the body tube "Ingr. Chevallier, Opticien, Place du Pont Neuf, Paris", indicating sale by J.G.A Chevallier (1778-1848) between 1842 and 1848. An example of this model is known that bears the trade label of Louis Mauss, Chicago, who was in business from 1857 until 1861. An illustration of this microscope appears in the 1856 catalogue of Benjamin Pike & Sons, New York. Charles Chevalier was a creative inventor and manufacturer of microscopes, whereas J.G.A. Chevallier largely sold microscopes acquired from wholesalers toward the end of his life, and Mauss and Pike definitely did not manufacture the instruments that they sold, altogether supporting the conclusion that Charles Chevalier manufactured all of those microscopes. Images adapted by permission from http://histoiredumicroscope.com/246-chevalier-charles-louis-1832/ or from private collections.

Figure 31A.

The mirror is signed "Charles Chevalier, Palais National 158", dating it to between 1849 and 1852. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Figure 31B.

The address of 158 Palais Royale dates this Charles Chevalier microscope to after 1852. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

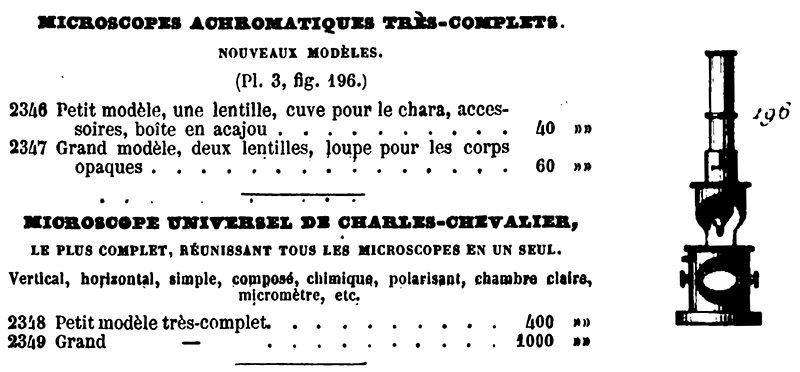

Figure 32A.

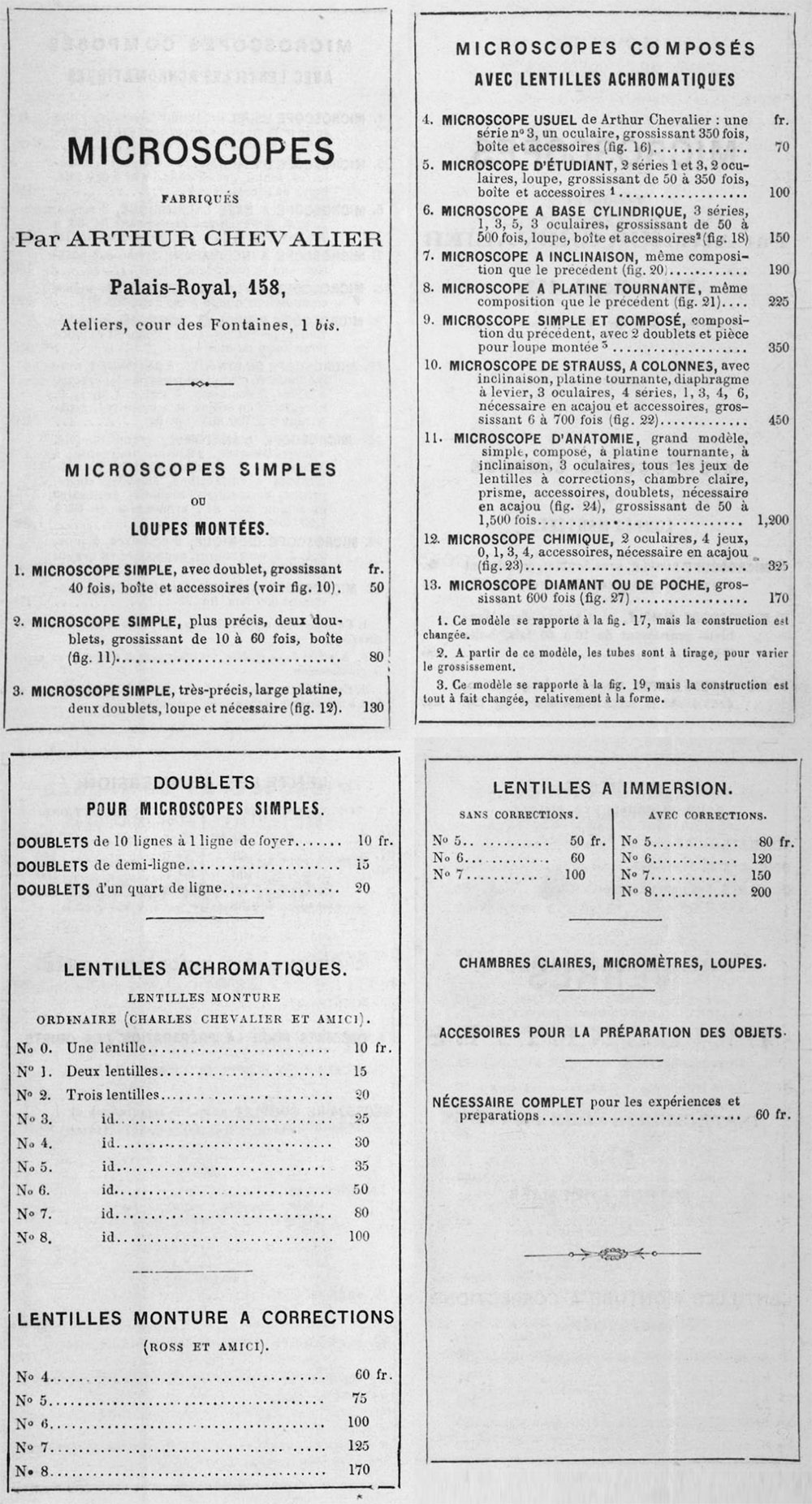

Microscope listings from Charles Chevalier’s 1856 "Catalogue des Appareils Photographiques". He listed the petit and grand models of the “Achromatique Universel”, and two sizes of simple drum microscopes, one of which was illustrated.

Figure 32B.

Engravings from Charles Chevalier's 1859 catalogue of microscopes.

Figure 33.

Lithograph from Arthur Chevalier’s 1864 "L’Étudiant Micrographe Traité Pratique" of a "perfected simple microscope of my father".

Figure 34.

An uncommon microscope slide that was sold by Charles Chevalier. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

________________________________________________________________________

Arthur Chevalier, 1859 - 1874

Arthur Chevalier took over his father’s business upon the latter man’s death. Henri van Heurck wrote in 1869 that Arthur made great strides to revive an enterprise that had been in decline, “(Arthur) took up the construction of micrographic instruments with great energy and success, the manufacture of which had been neglected by his father in the last years of his life, due to the poor state of his eyesight”.

Arthur published an important, comprehensive book on microscopy in 1864, L’Etude Micrographe. This book presented both general information on microscopy and descriptions of instruments manufactured by him and by his father (Figure 36). An expanded edition appeared in 1865, showing additional microscope models, while deleting models that were presumably obsolete (Figure 37).

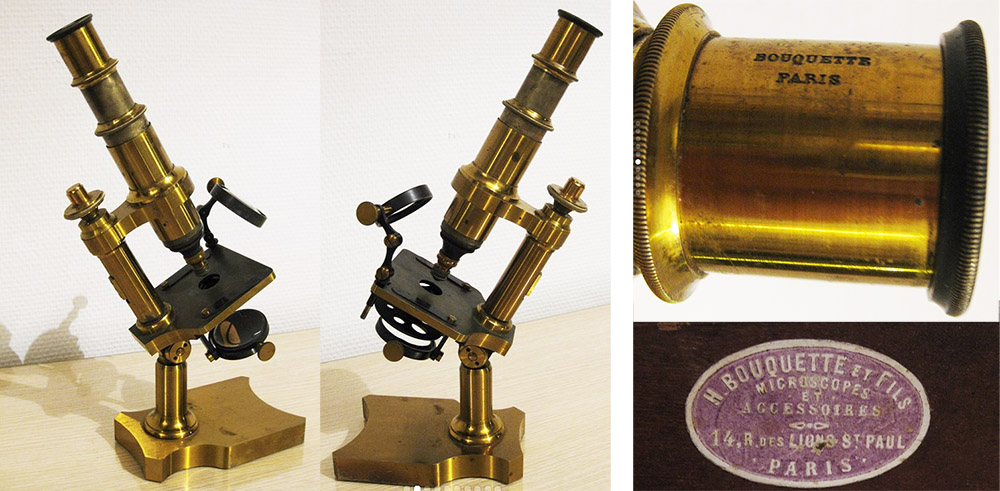

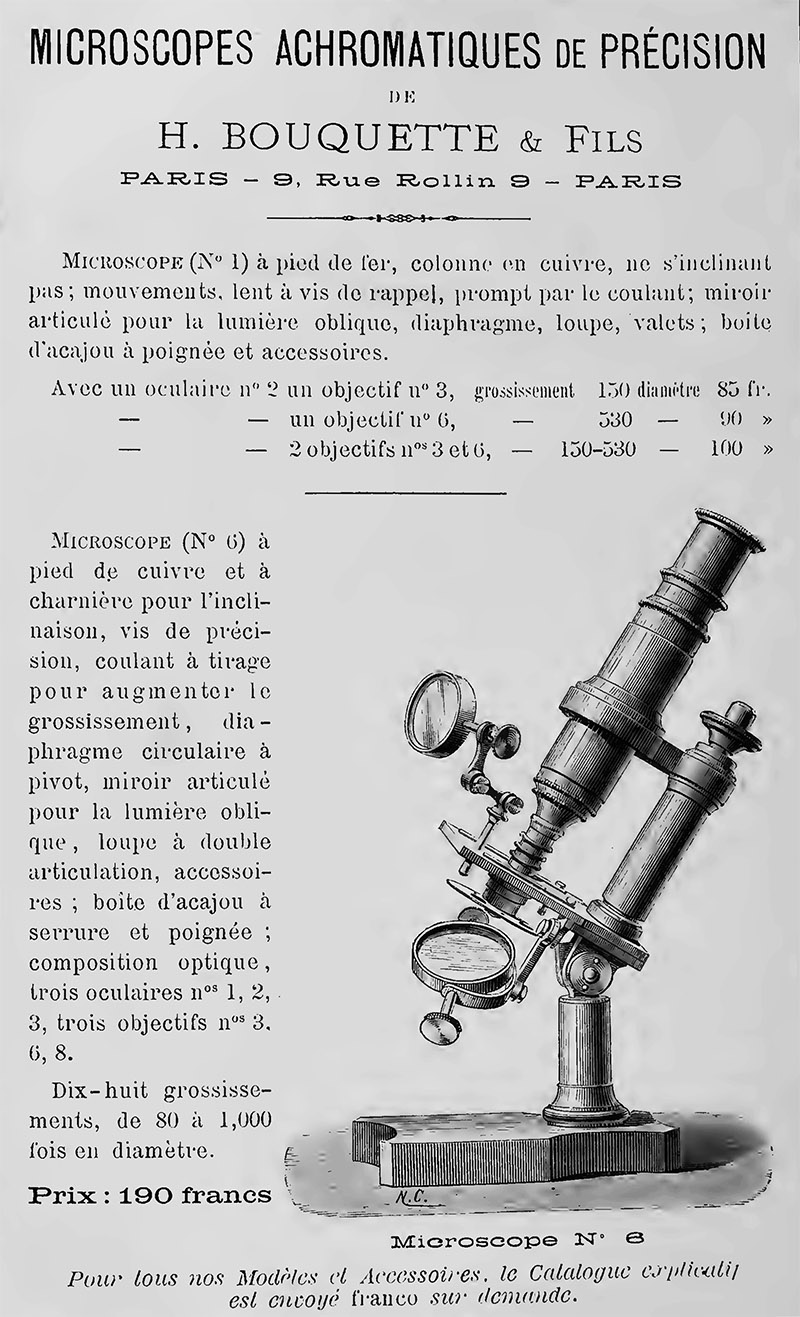

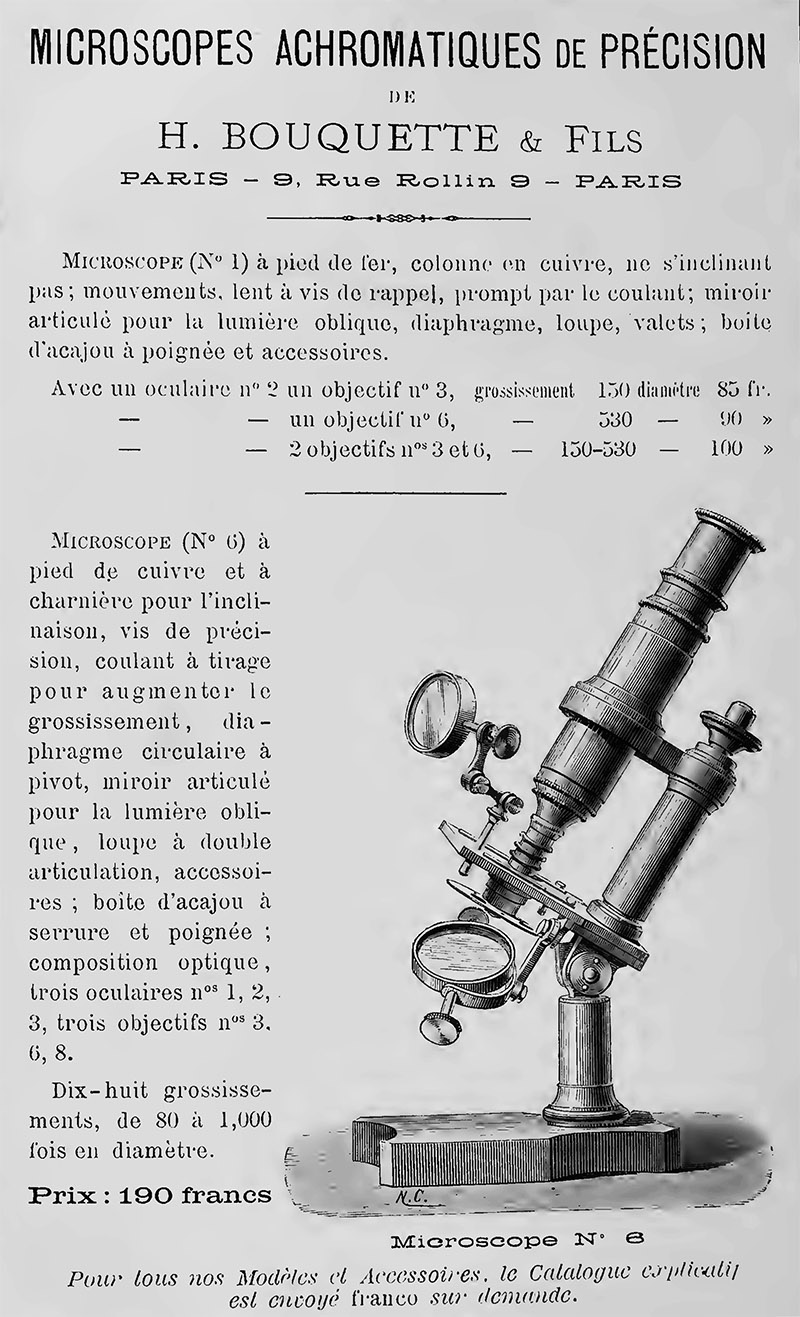

Jules Pelletan noted that several of Chevalier’s stands copied the developments of Camille and Alfred Nachet, such as the drum and “Strauss”-model horseshoe-footed compound microscopes. Additionally, production of microscope bodies was outsourced to craftsmen such as Henri Bouquette (Figures 57-58). Yet these were of high quality, Pelletan remarking that “the microscopes were very well made”, and that Bouquette was “a very skilled mechanical engineer” who produced “bodies of microscopes that are irreproachable as regards the mechanism”.

In 1870, Arthur was presented with an honorary doctoral degree from the University of Rostock. From then onward, he used the title “Doctor” for his signature on microscopes and other equipment.

Yet Arthur was seriously ill, and died at the age of 43, in 1874.

His wife died the next month. Ownership of the business passed to their young daughters. One by one, they also died young, the last in 1880.

Charles and René Avizard bought the Chevalier business in 1881 by two brothers, but retained the name “Dr. Arthur Chevalier”. It remained under their ownership and that name until ca. 1914-1921, when the Avizards merged the Chevalier business with that of J.G.A. Chevallier, which they had purchased in 1883.

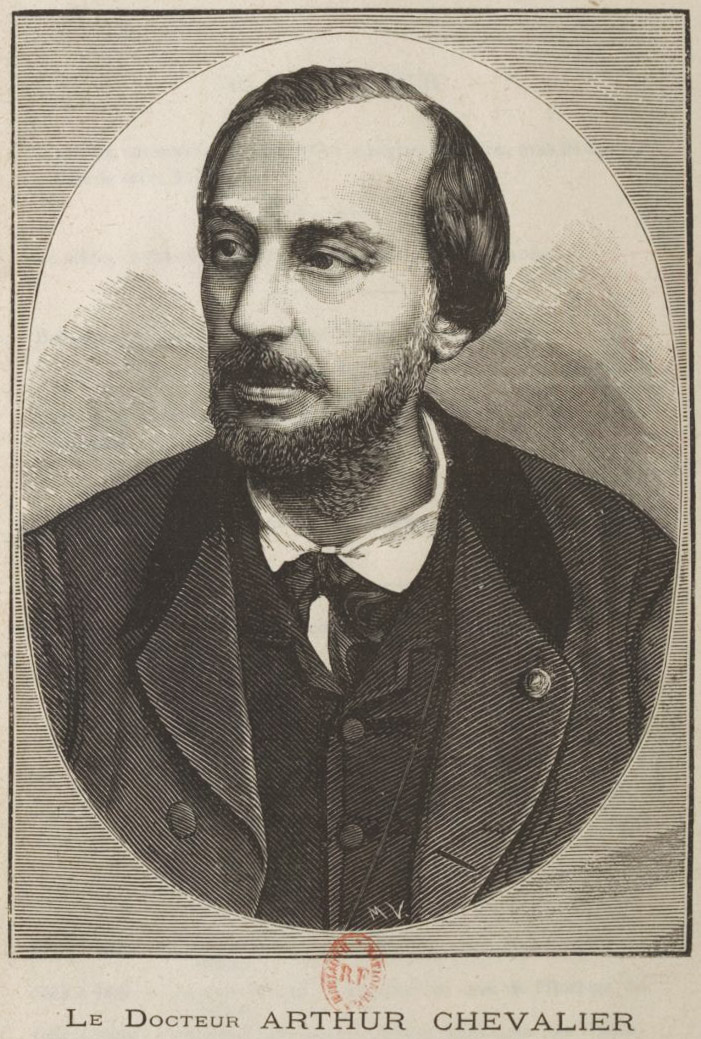

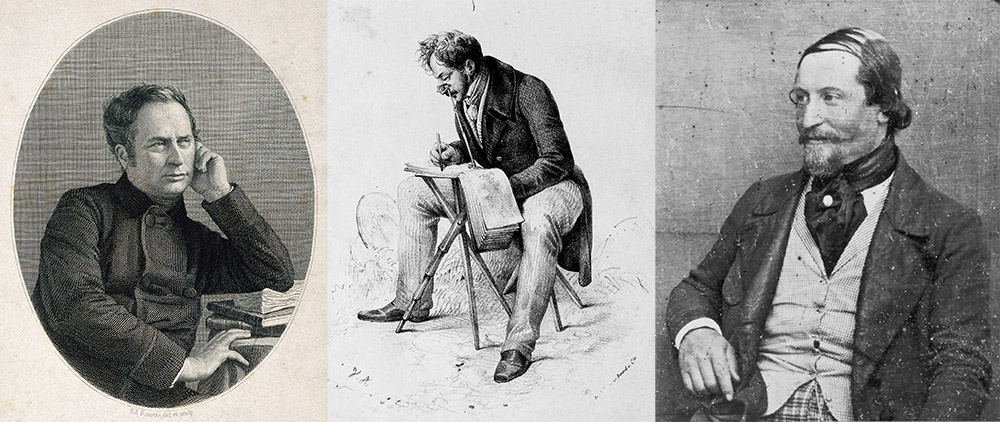

Figure 35.

Arthur Chevalier, from the 1882 edition of “L’Etudiant Micrographe”.

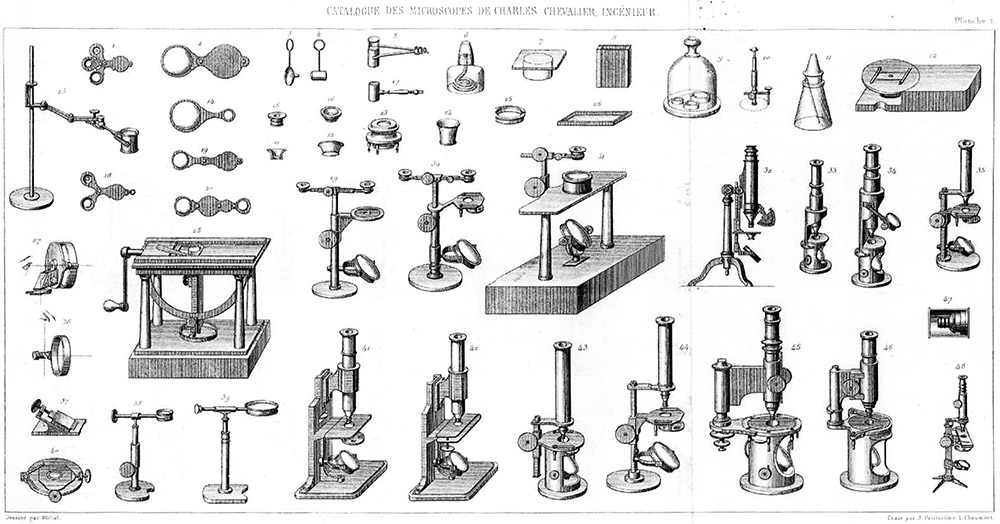

Figure 36.

Arthur Chevalier’s microscopes, as illustrated in the 1864 edition of “L’Etudiant Micrographe”.

(A) Simple microscope, new model.

(B) Precision simple microscope.

(C) Standard compound microscope. (D) Student compound microscope.

(E) Cylindrical base compound microscope.

(F) Simple / compound microscope.

(G) Inclining compound microscope.

(H) Rotating compound microscope.

(I) “Strauss” compound microscope with columns (See Figure 39 legend for information on Strauss)

(J) Chemical microscope of Charles Chevalier’s form.

(K) Large anatomical microscope.

(L) “Diamond” pocket microscope.

(M) Small Universal microscope.

(N) Large Universal microscope.

The 1865 edition of “L’Etudiant Micrographe” included only some of these microscopes: A (in three revised forms),

C,

E,

G,

H,

I,

J,

M, and

N, along with several new models (Figure 37, below).

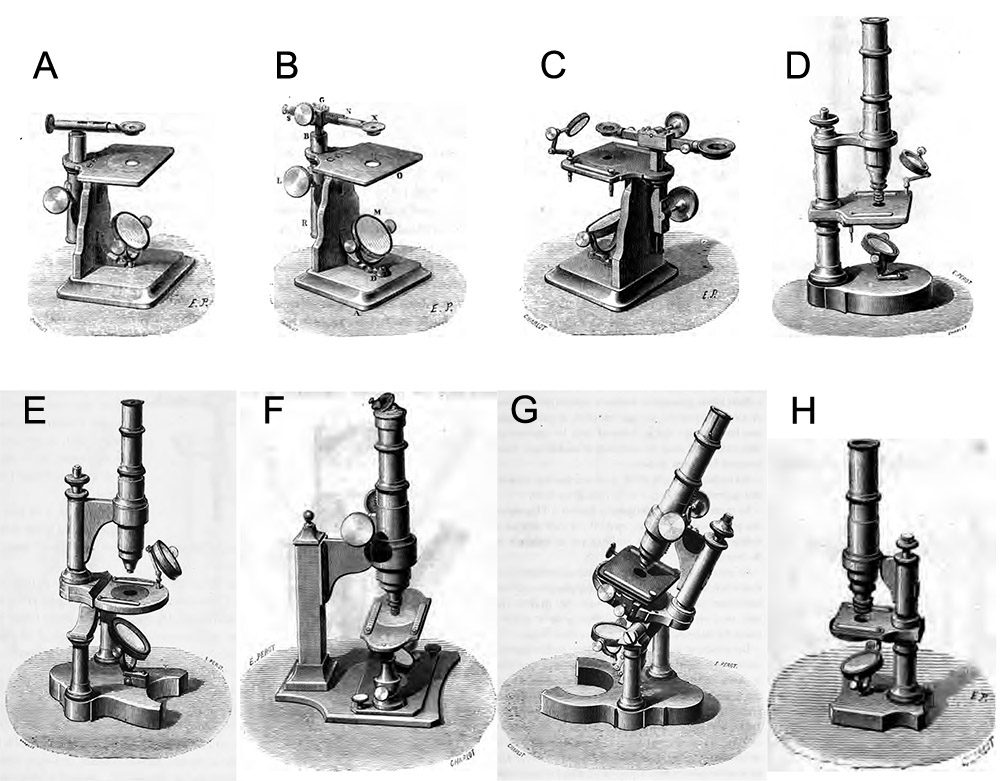

Figure 37.

Additional microscopes that were described in Arthur Chevalier’s 1865 edition of “L’Etudiant Micrographe”. Several of the stands shown in the 1864 edition were no longer included.

(A-C) Variations on a simple microscope, with A having an arm whose length can be adjusted by screw on the end (similar to Raspail’s device), B has a rack-and-pinion to adjust the arm length, and C has two lens-holders on the arm that permit easy changes of magnification.

(D) Student compound microscope.

(E) Simple / compound microscope.

(F) Compound microscope on a design by Professor Charles Robin.

(G) Large “Strauss” compound microscope with columns (See Figure 39 legend for information on Strauss).

(H) A new form of “Diamond” pocket microscope (Chevalier states that it was invented by his father in 1834, but this is clearly a newer style, and is very different from the “Diamond” that he showed in 1864: See Figure 35-L, above).

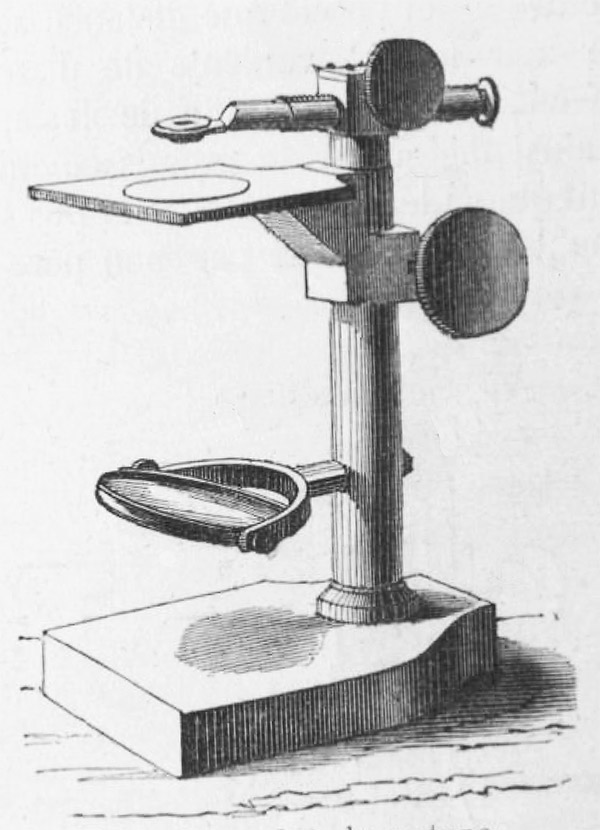

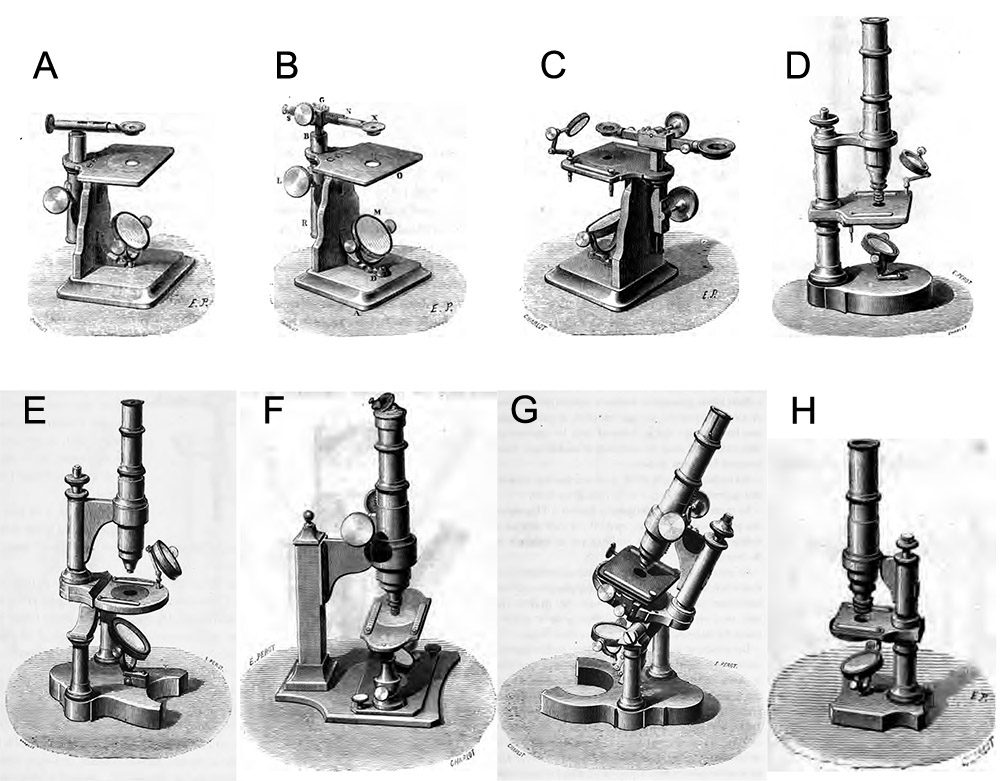

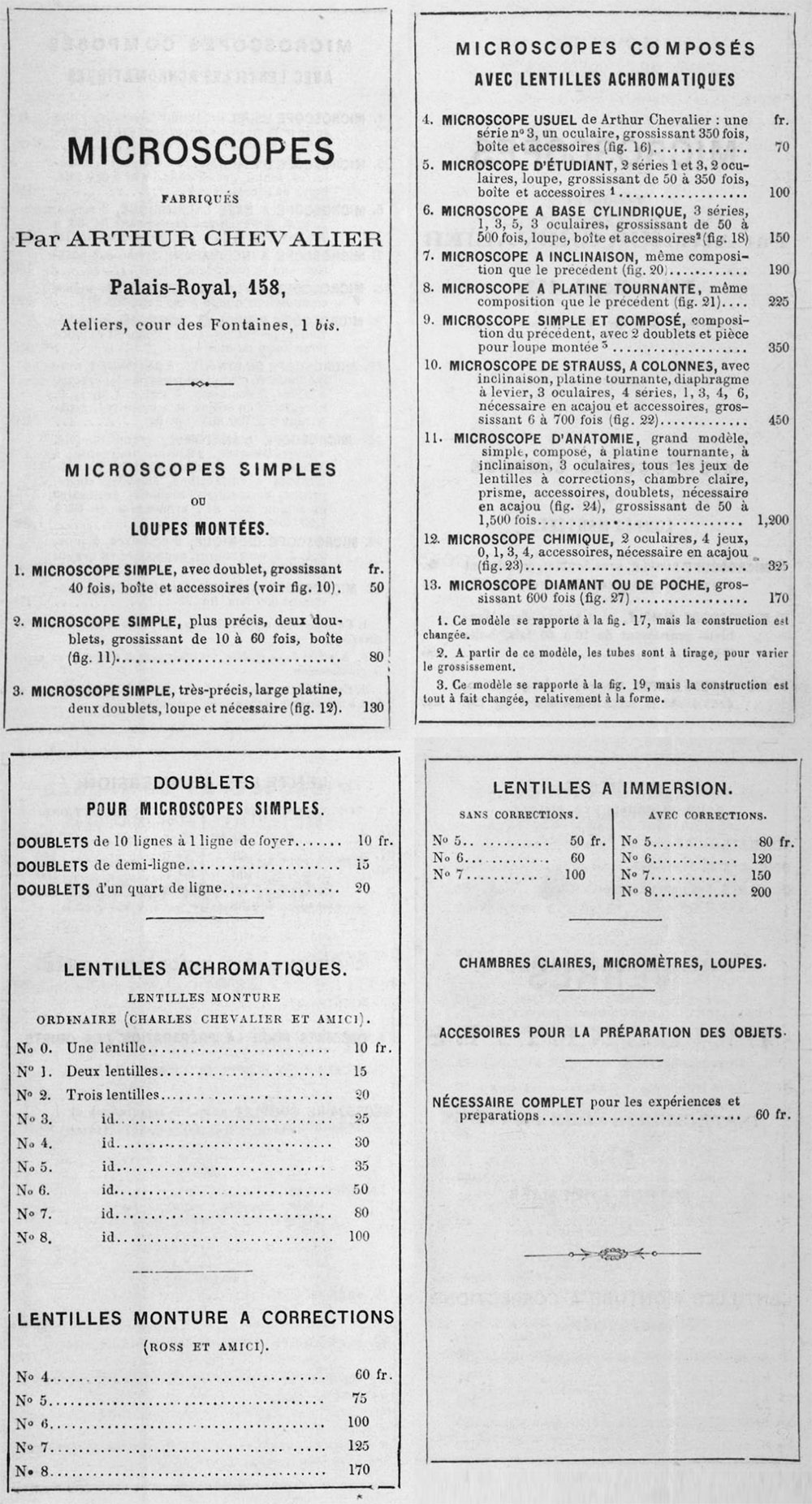

Figure 38.

Arthur Chevalier’s microscope price list, from the 1885 edition of “L’Etudiant Micrographe”. Lithographs of each instrument is shown above in Figures 36 or 37: (1-3) Figure 37A-C; (4) Figure 36-C; (5) Figure 37-D; (6) Figure 36-E; (7) Figure 36-G; (8) Figure 36-H; (9) Figure 37-E; (10) Figure 36-I; (11) Figure 37-G; and (12) Figure 37-H.

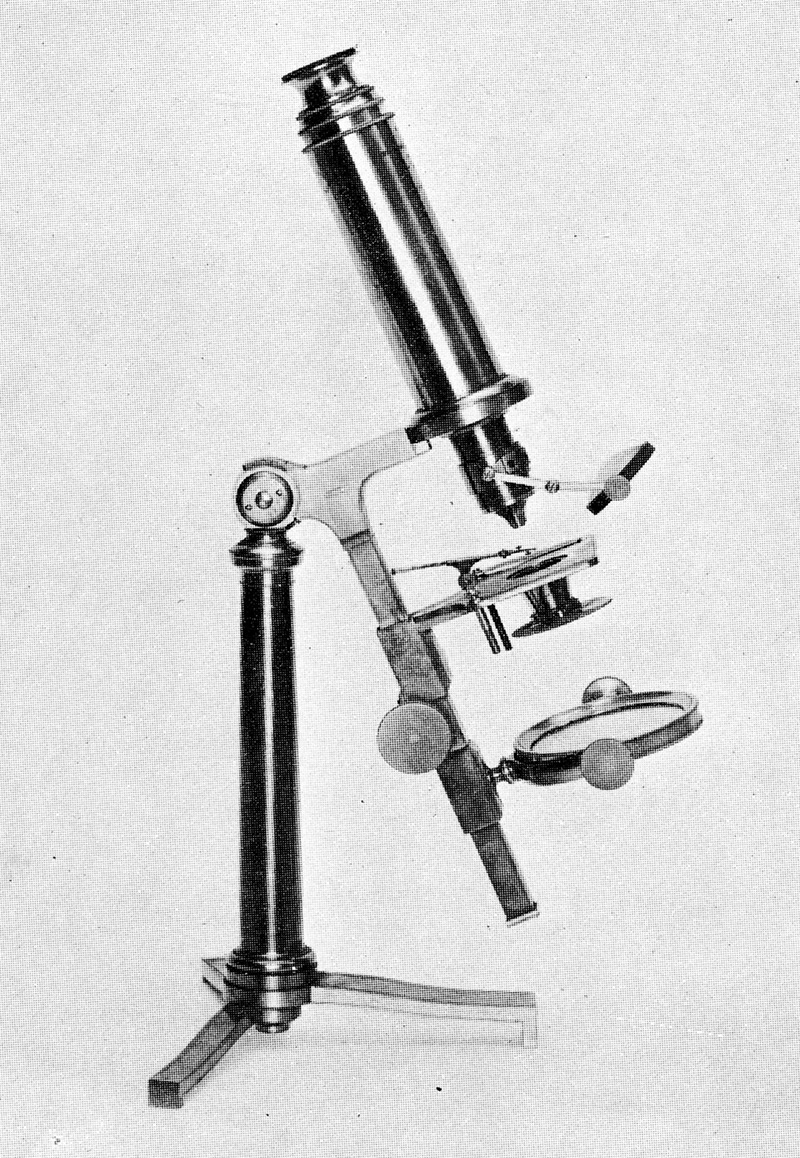

Figure 39.

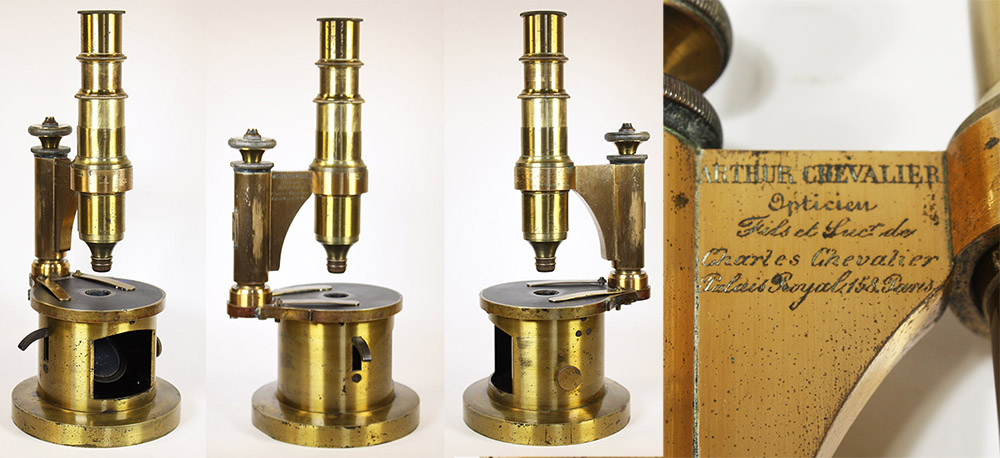

A standard (“usuel”) microscope by Arthur Chevalier (see Figure 36-C). The signature lacks reference to Arthur’s doctorate, and so dates to before 1870.

Figure 40.

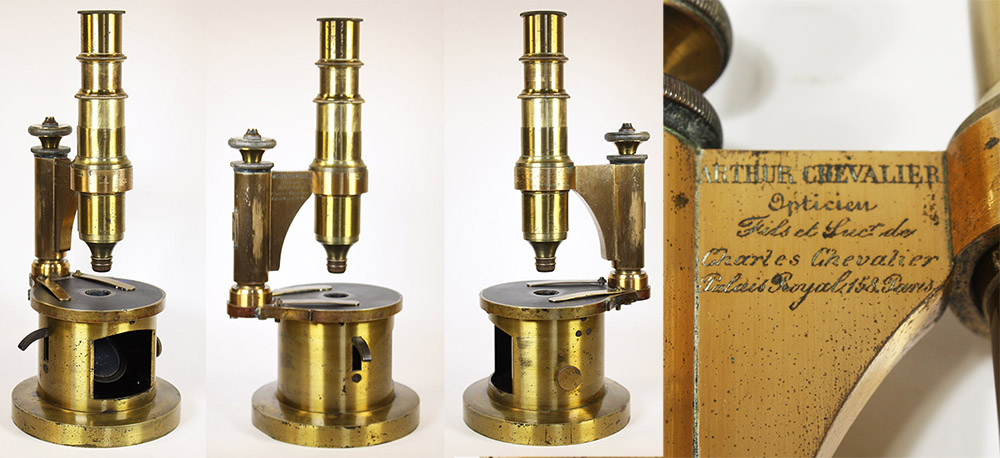

A drum-style ("cylindrical") microscope of the 1864 style shown in Figure 36, signed “Arthur Chevalier, Opticien, Fils et Sucr. de Charles Chevalier, Palais Royal 158, Paris”. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet sale site.

Figure 41.

A different pattern of Chevalier drum/cylindrical microscope. It is also signed “Arthur Chevalier, Opticien, Fils et Sucr. de Charles Chevalier, Palais Royal 158, Paris”. The arm is different from the one illustrated in the 1864 and 1865 editions of “Etude de Micrographe”; thus, at least two forms of this instrument were produced.

Figure 42.

Rotating compound microscope, signed “Arthur Chevalier, Palais Royal 158, Paris” (see Figure 36-H). A number of early French microscopes have stages and upper bodies that rotate, which allows views of the specimen with different substage illumination angles without touching the specimen or the mirror. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet sale site.

Figure 43.

A small Universal microscope, signed “Microscope Achromatique Universel, Invente par Charles Chevalier, Ingeneur, Arthur Chevalier Fils et Sucr., Palais Royal 158, Paris” (see Figure 36-M). Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from Brian Bracegirdle “Science Museum, London”.

Figure 44.

Simple microscope (see Figure 37-A), signed “Dr. Arthur Chevalier”, dating its production to after 1870.

Figure 45.

A simple Arthur Chevalier microscope, with rack-and-pinion controls of the focus and arm-length (see Figure 37-B). Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet sale site

Figure 46.

“Student” microscope, signed “Arthur Chevalier” (i.e. pre-1870). This model was described in the 1865 edition of “L’Etudiant Micrographe”. A very different form of “Student” microscope was described in the 1864 edition (see Figure 36-D).

Figure 47.

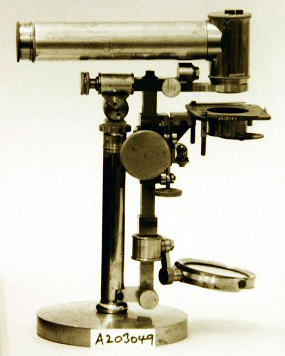

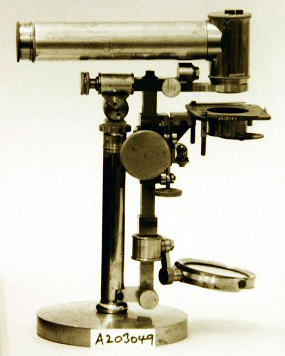

Compound microscope, based on a design by anatomist Charles Robin (1821-1885). Described by Chevalier in 1865 (see Figure 37-F). Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co118896/compound-monocular-microscope-by-arthur-chevalier-compound-monocular-microscopes.

Figure 48.

Signed on the stage “Arthur Chevalier” and “Le Trichinoscope”. Arthur published a booklet describing this microscope in 1866. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from internet auction sites.

Figure 49.

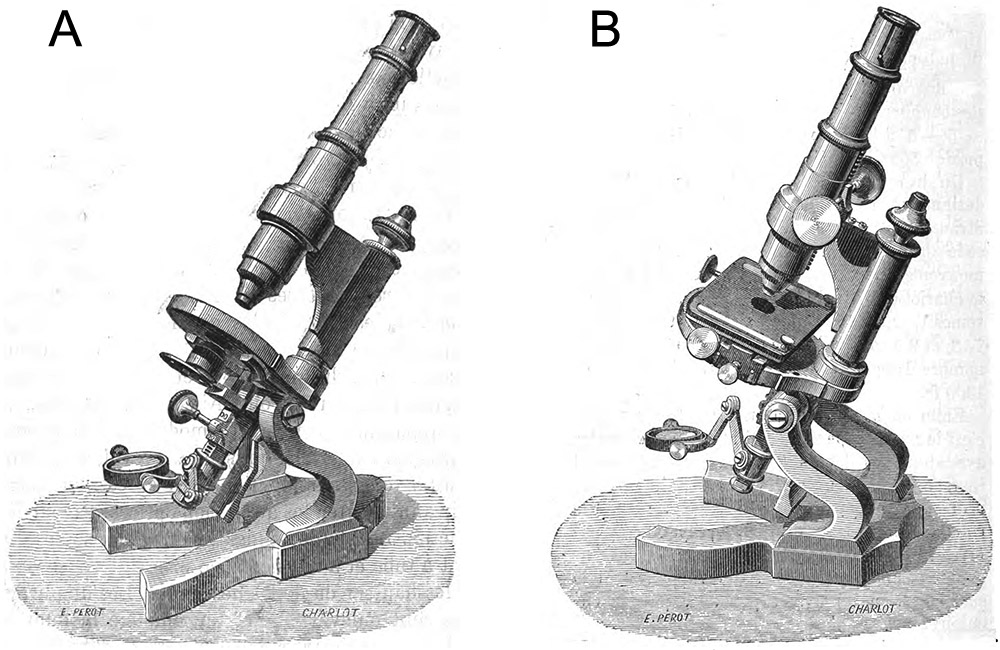

Two ca. 1869 forms of Arthur Chevalier microscopes, described by Henri van Heurck in his “Le Microscope”, second edition, 1869. Both are described as “Strauss” forms, with B being the “large” model. “Strauss” was Hercule Strauss-Durckheim (1790-1864), a French anatomist and entomologist, who has been suggested to have been involved with development of the open “horseshoe” foot of the “continental” microscope (see Nias, 1893, JRMS). The first such microscope was produced by Georges Oberhaueser in 1849, which Oberhaeuser named the “Continental” stand. Evidently, Chevalier was calling attention to his microscopes’ open feet without mentioning his competitor’s instrument.

Figure 50.

A “Strauss” microscope (see Figure 49), signed “Arthur Chevalier, Palais Royale”, dating to before Arthur’s 1870 honorary doctoral degree. The foot shape and absence of rack-and-pinion focusing indicate it to be the“moyen” (“medium”) “Strauss” model. Note that the stage and upper body rotate around the lower assembly. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet sale site.

Figure 51.

A large “Strauss” microscope; note the rack-and-pinion focusing and shape of the foot. It is signed “Docteur Arthur Chevalier, Palais Royale, Paris”. The signature dates this instrument to after Arthur’s 1870 honorary doctoral degree. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://www.mhs.ox.ac.uk/collections/imu-search-page/record-details/?thumbnails=on&irn=5881&TitInventoryNo=45666.

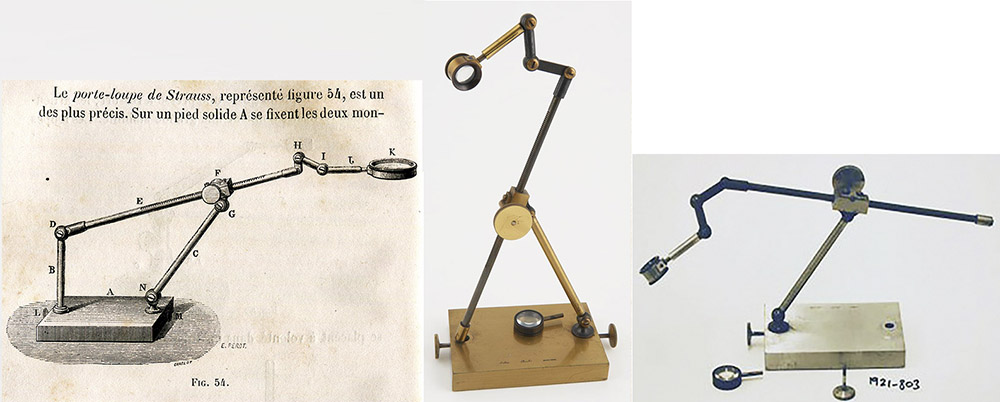

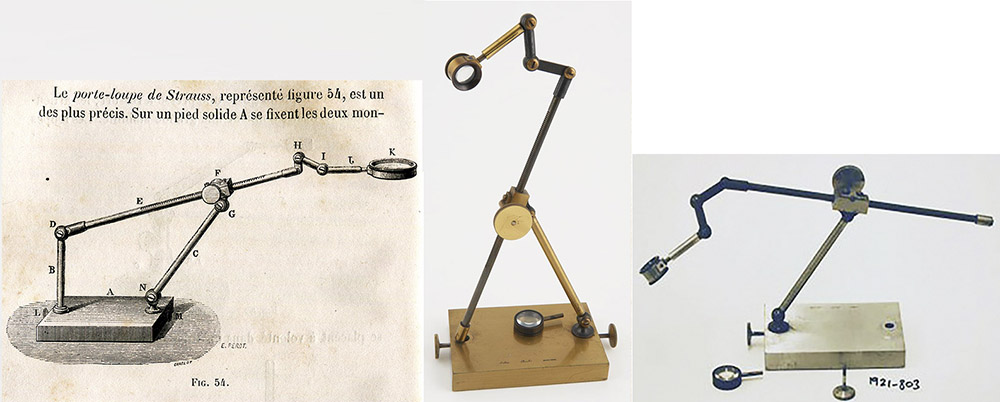

Figure 52.

The Chevaliers also produced simple magnifiers, such as the "Porte-loupe de Strauss" (Strauss's magnifying glass holder). The image on the left is from the 1865 edition of Arthur’s “Le Etudiante Micrographe”. This instrument was new that year, as it was not described in the 1864 edition. The center and right images are of an example signed by Arthur Chevalier, and were adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co8291/single-microscope-by-chevalier-microscope.. and Brian Bracegirdle “Science Museum, London”. Rod "B" and hinge "D" have been lost from this example

Figure 53.

A folding Coddington-type magnifying glass, signed “Arthur Chevalier, Palais-Royale”. About 1.5 inches / 4 cm long. The date of manufacture is not known. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Figure 54.

Illustrations of Chevalier microscopes from the 1878 publication “Les Microscopes Chevalier”. This was four years after Arthur’s death, when the business was managed for his daughters by the Avizards. The lithographs include instruments that had been produced by the Chevaliers for decades, plus several new forms. Surviving examples of the microscope shown in the bottom row, center, are presented in Figures 56 and 57, below.

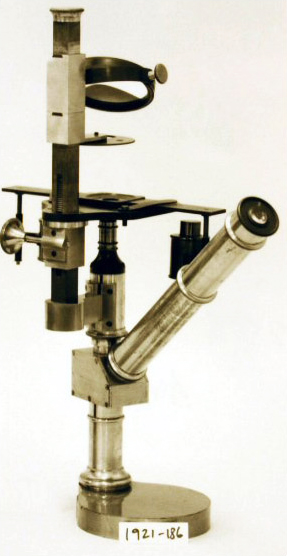

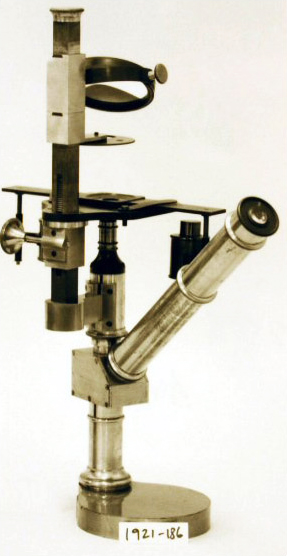

Figure 55.

Circa 1878 inverted microscope, signed “Dr. Arthur Chevalier, Opticien, Palais Royal à Paris” (see Figure 54). Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from Brian Bracegirdle “Science Museum, London”.

Figure 56.

A post-1870 inclining compound microscope, signed “Dr. Arthur Chevalier”. It is identical to the 1878 illustration shown in Figure 54 (bottom row, center) The foot and mirror attachment are different from the ca. 1864 inclining model that is shown in Figure 36-G. Adapted by permission from http://www.lecompendium.com/dossier_optique_224_microscope_inclinable_arthur_chevalier/microscope_inclinable_arthur_chevalier.htm.

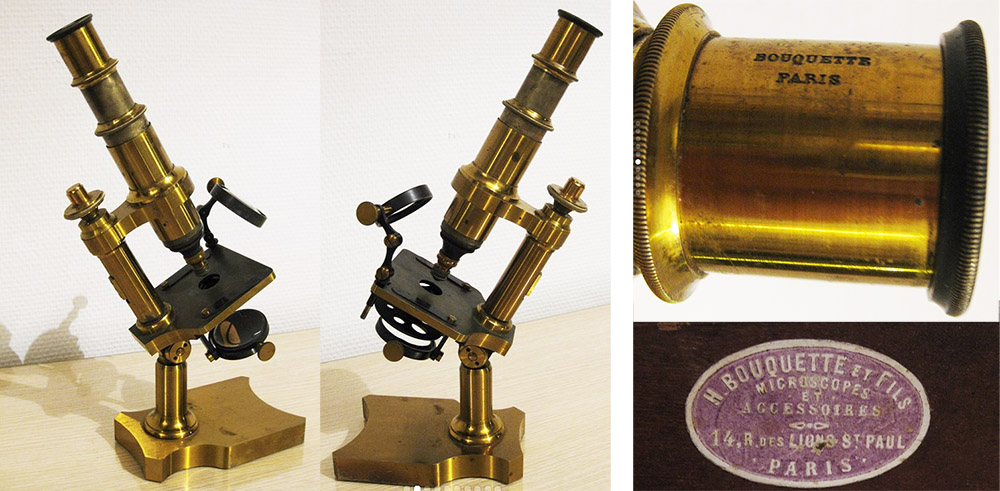

Figure 57.

A microscope that is identical to the Chevalier-signed instrument in Figure 56, except that it is signed “Bouquette Paris”. A label from “H. Bouquette et Fils” is pasted inside its cabinet. A lithograph of this same model was included in an 1887 advertisement from Bouquette (Figure 86, below). Jules Pelletan wrote in 1879, “in Arthur Chevalier's time the microscopes were very well made, in general, especially the large and medium models, which were called ‘the large’ and ‘the small Strauss’ and which reproduced roughly the two large models of Nachet. They were built by Mr. Bouquette, a very skilled mechanical engineer, whose son is still manufacturing, both for his own account and for the former Arthur Chevalier house, bodies of microscopes that are irreproachable as regards the mechanism”.

Figure 58.

(Left) a ca. 1865-1870 “Student” microscope signed “Arthur Chevalier, Palais Royale 158, Paris” and (right) an identical microscope signed “Bouquette, 9 Rue Rollin”. Adapted for educational, nonprofit purposes from http://golubcollection.berkeley.edu/19th/317.html.

________________________________________________________________________

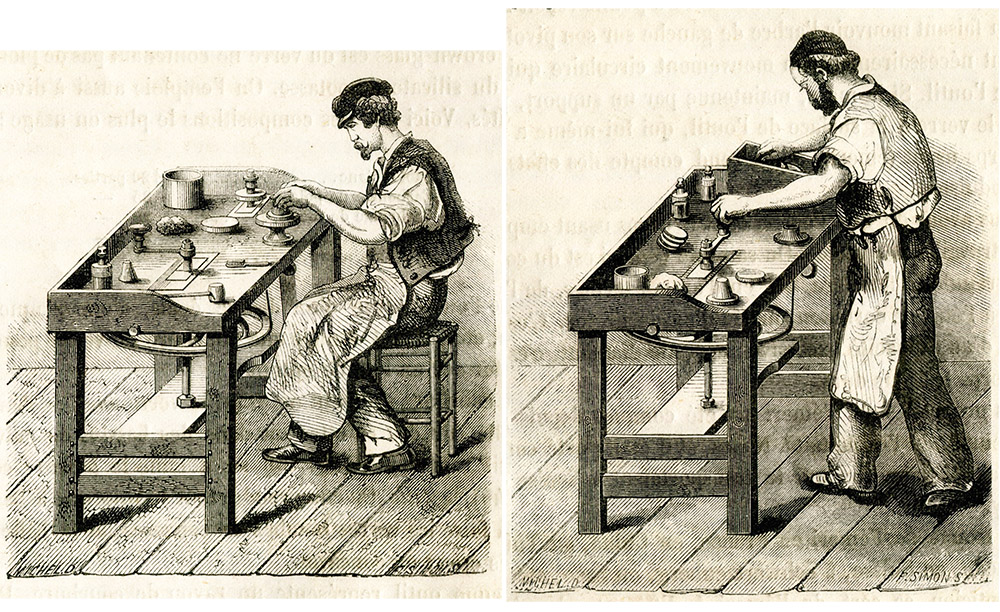

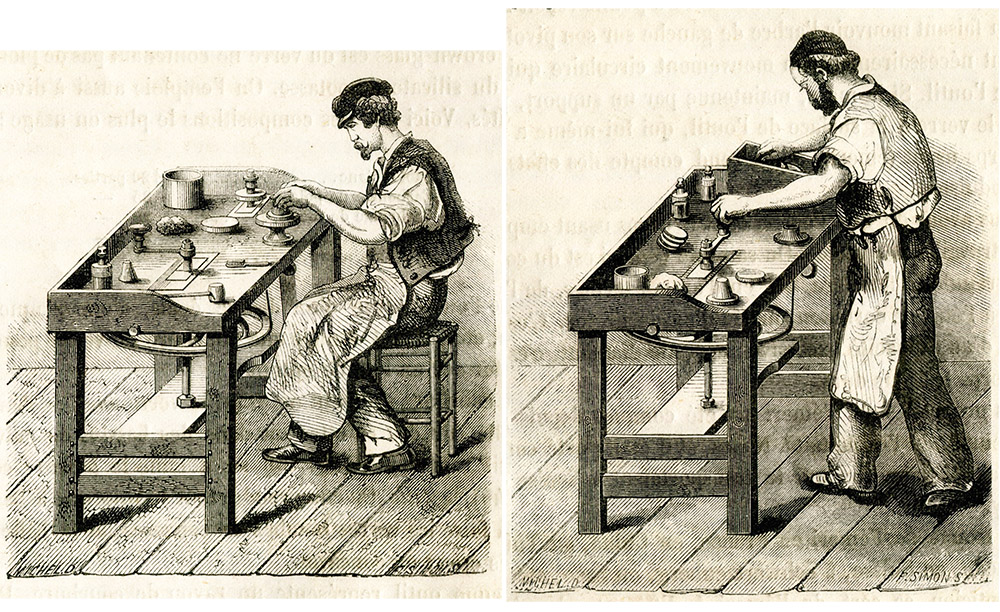

Figure 59.

Two lens-grinders at work, from A. Chevalier, “L'étudiant Micrographe”, 1865.

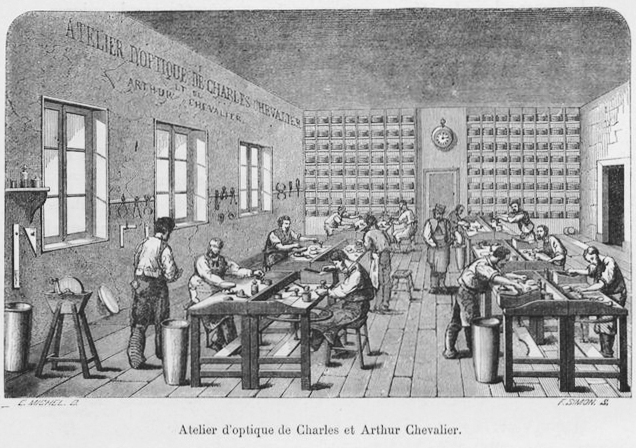

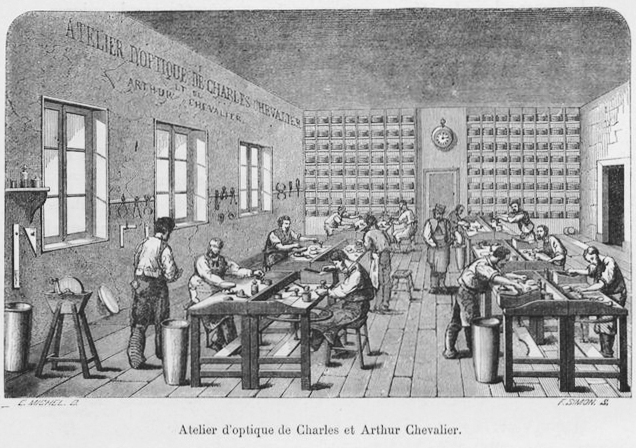

Figure 60.

Engraving of the Chevalier lens-grinding workshop. From “Les Microscopes Chevalier”, 1878.

________________________________________________________________________

The history of the House of Chevalier as optical instrument manufacturers began in 1757. In that year, Claude-Henriette Christophe Chevalier, widow of a painter named Philibert-Vincent Chevalier, arranged for her son, Louis-Vincent Chevalier to be apprenticed to mirror-maker Etienne-Claude Deslandes. According to family history, Louis-Vincent was then thirteen and a half years old, indicating a birthdate of 1744 or 1745.

Following that apprenticeship, Louis-Vincent Chevalier opened his own shop on Quai de l’Horloge, in 1865. Some later advertisements state a beginning in 1860 or 1870, but 1865 is the most commonly-cited date. It indicates a 7-8 year apprenticeship, which is a normal duration.

Son Jacques-Vincent (Vincent) Chevalier was born on December 23, 1770.

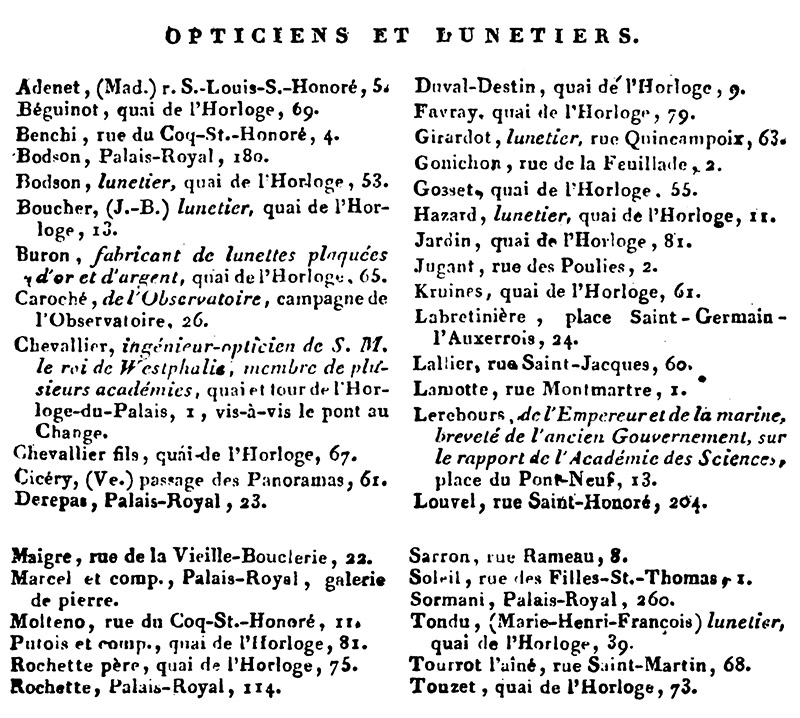

Louis-Vincent Chevalier died in 1805, and his business was continued by Vincent Chevalier. The 1809 Almanach du Commerce de Paris listed Vincent as “Chevalier fils”, at 67 Quai de l’Horloge (Figure 61). That address changed to number 69 sometime after 1813, probably due to a renumbering of the street. The suffix “fils” was dropped by the 1813 edition of the Almanach.

Vincent Chevalier had married ca. 1803, to Marie Madeleine Wagener. Their son, Charles Louis, was born on April 18, 1804.

Vincent had a brother, Jean Louis Joseph Chevalier, who lived from 1776 until 1848. Known as “Louis”, records of his 1810 marriage listed his parents as Louis-Vincent Chevalier and Charlotte Victoire Penseron. After serving for some time in the army, Louis Chevalier worked for a number of years with other optical businesses. In 1818, Louis established his own optical shop at 65 Quai de l'Horloge. After his death, the business continued as Louis Chevalier et Fils, at 25 Quai de l'Horloge. There do not appear to have been any business ties between Louis and either Vincent or Charles Chevalier.

At the 1819 Exposition des Produits de l’Industrie, “M. Chevalier (Vincent) aîné” was awarded a Citation for “divers instrumens d’optique exécutés avec adresse”. Explanation of those “various optical instruments” was not provided. The description of Vincent as “aîné” (the elder) may be a reference to Louis Chevalier, whose shop was close by, or may indicate that Vincent's son, Charles, was becoming known to the scientific world.

On November 5, 1820, Vincent presented a new form of camera obscura to the Société d'Encouragement pour l'Industrie Nationale. Such a device consists of a small hole that allows external light into a dark box or room, the result being that an image of the outside is projected onto the opposite wall of the chamber. Chevalier’s device was unique in having a prism in the hole, with one face of the prism being convex. It was reported to produce vivid, sharp images, and lacked the disadvantages of a mirror, which had previously been used for these devices.

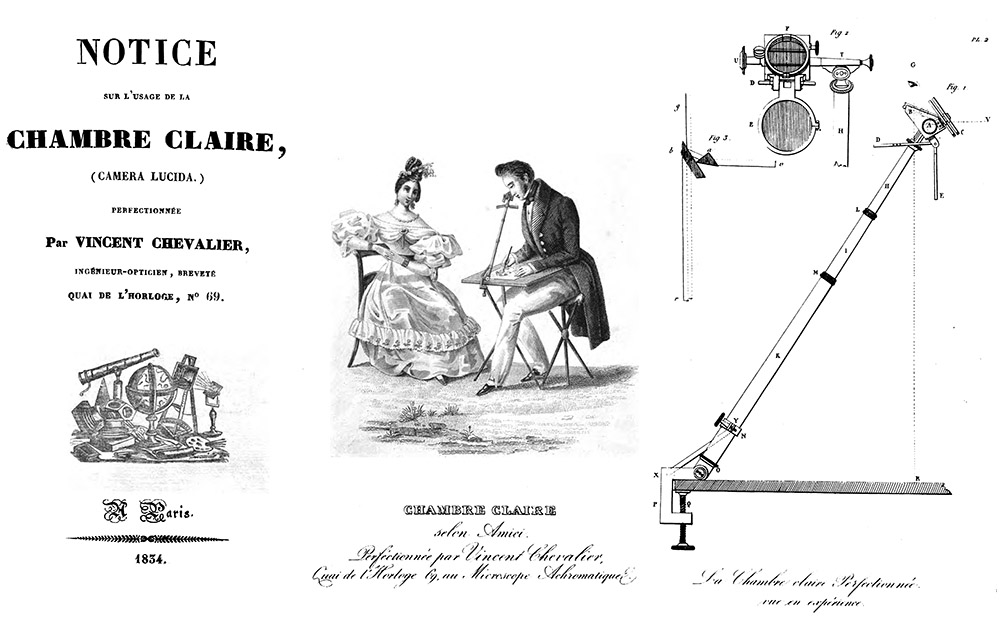

At the same time, Chevalier received acclaim for his production of a camera lucida. This device has a prism that permits the user to simultaneously see an object and a sheet of paper, thereby allowing the user to trace the object on the paper. It was described as “supérieur aux autres du même genre, en ce qu'il permet de bien distinguer l'image et la pointe du crayon” (“superior to others of the same kind, in that it makes it possible to clearly distinguish the image and the point of the pencil”). Moreover the Chevalier model was “augmenté d'un appareil microscopique qui donne la faculté de pouvoir dessiner la forme amplifiée des insectes et autres objets de petite dimension” (“augmented by a microscopic device which gives the ability to draw the magnified form of insects and other small objects”). This final point clearly indicates that Vincent Chevalier was producing magnifying lenses by 1820.

Also of significance, the Chevalier camera lucida was based on an invention of Giovanni Battista Amici (1786-1863), of Modena, Italy. Amici and the Chevaliers are known to have exchanged optical items. Noting that Amici was then developing his “catadioptric” microscope, which used a miniature concave mirror for magnification, and that Vincent Chevalier’s father was trained as a mirror-maker, it is possible that Vincent provided mirrors, or at least, advice, to Amici.

Vincent was awarded an Honorable Mention at the 1823 Exposition des Produits de l’Industrie for his “instrumens d’optique” and measuring devices.

The Chevaliers began their careers as significant microscope manufacturers in 1823. Alexandre François Gilles (a.k.a. “Selligue”) enlisted their help in developing an achromatic compound microscope. Chromatic aberration arises because the various wavelengths of white light refract through a magnifying lens at different angles, resulting in an image with a blur of colors. Selligue extended upon the work of earlier optical engineers and developed a combination of four glass lenses of different curvature and composition that essentially cancelled each others’ chromatic aberration, producing a magnified image with minimal aberration (Figure 2).

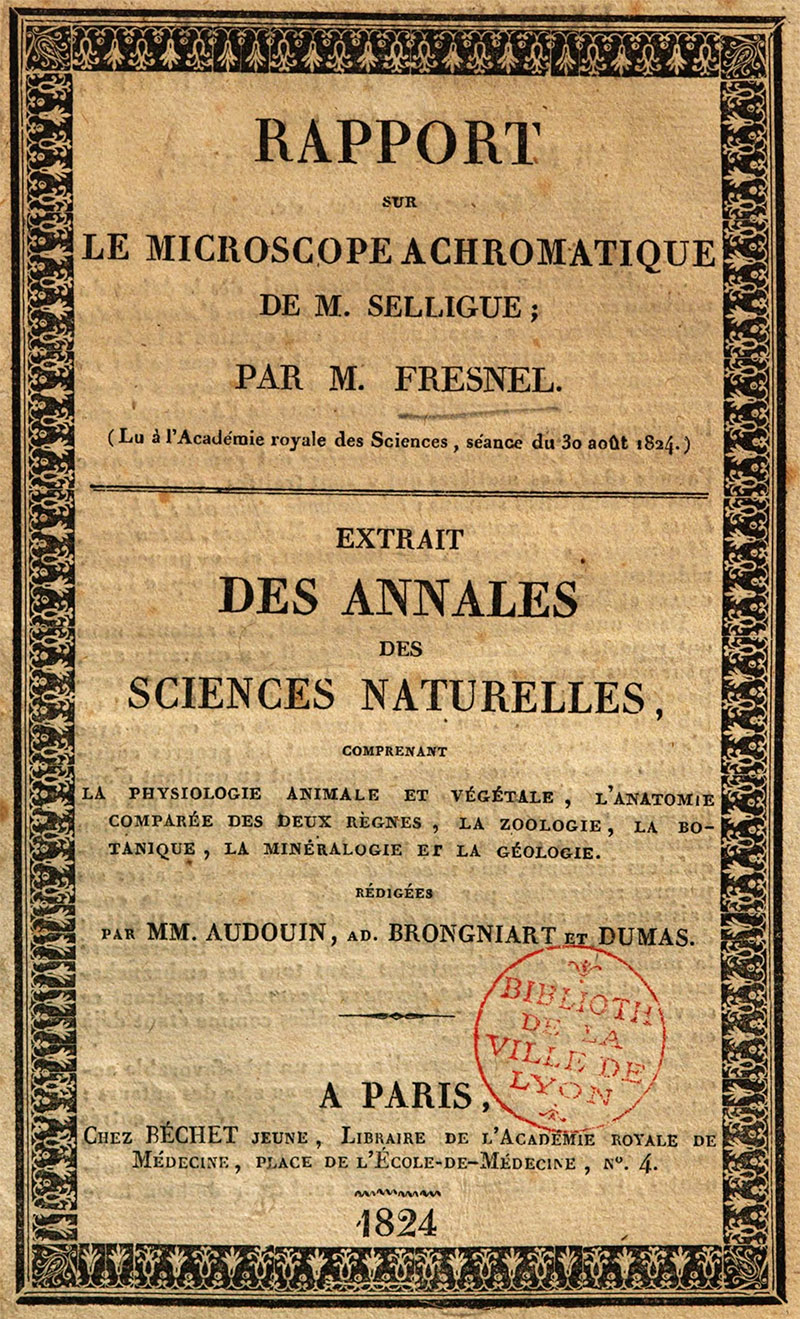

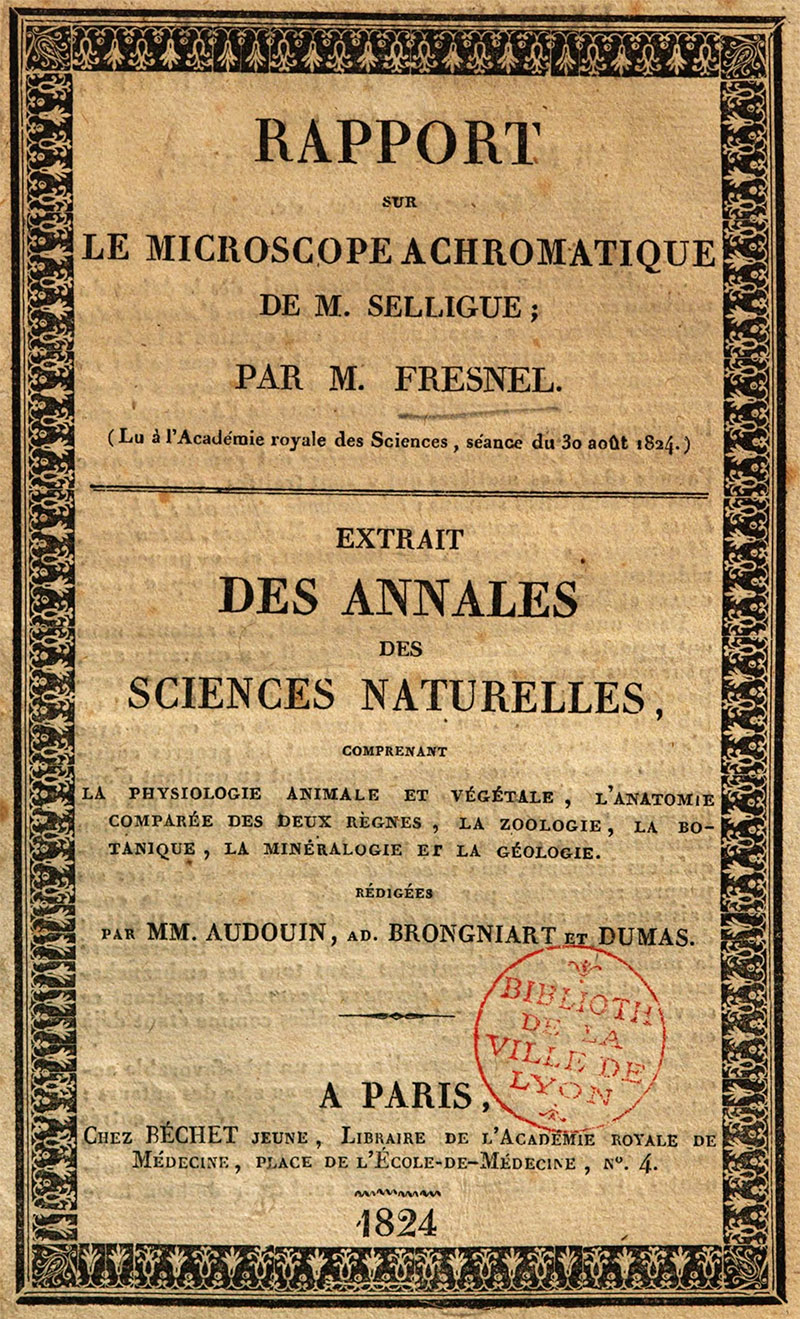

On August 22, 1824, the Selligue-Chevalier achromatic microscope was presented to l’Académe Royale des Sciences by optical engineer and physicist Augustin Fresnel (1788-1827) (Figure 62). However, Fresnel gave Selligue sole credit for this major development. Essentially, the Chevaliers were considered nothing more than workmen who followed Selligue’s orders. Offended, the Vincent and Charles cut off work with Selligue. The latter man turned to another optician who had a shop nearby, Jean Gabriel Augustin Chevallier (a.k.a. "l’Ingénieur Chevallier", lived 1778-1848), who then produced “Selligue” microscopes for several years afterward.

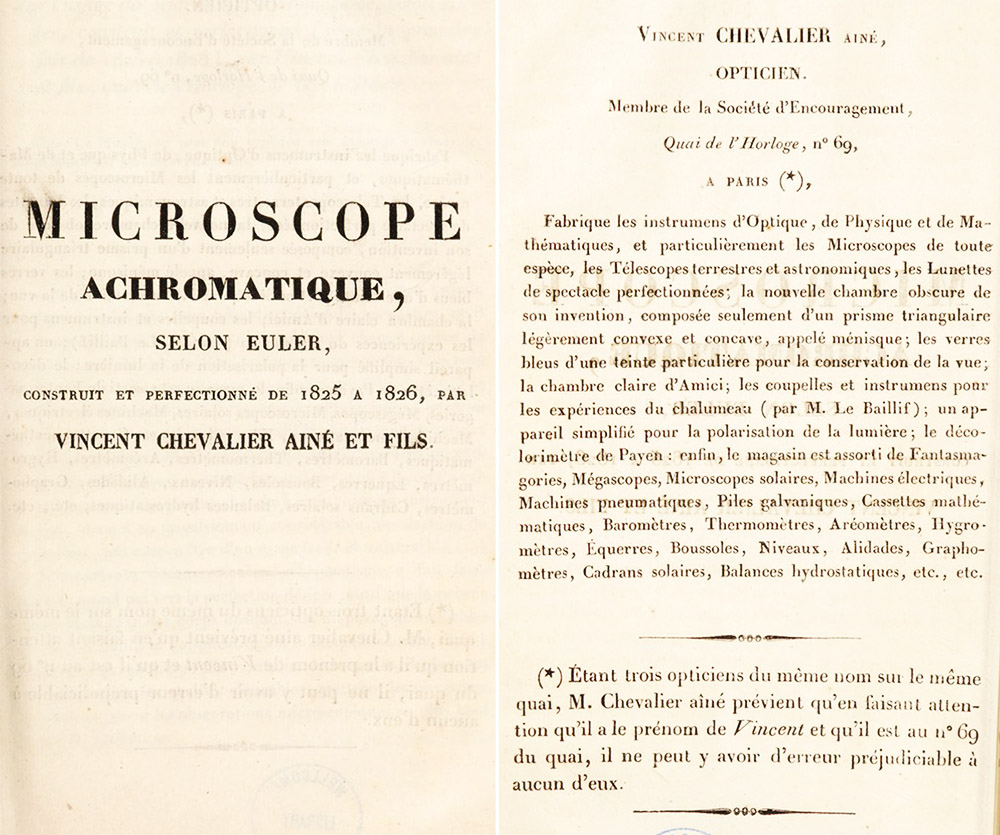

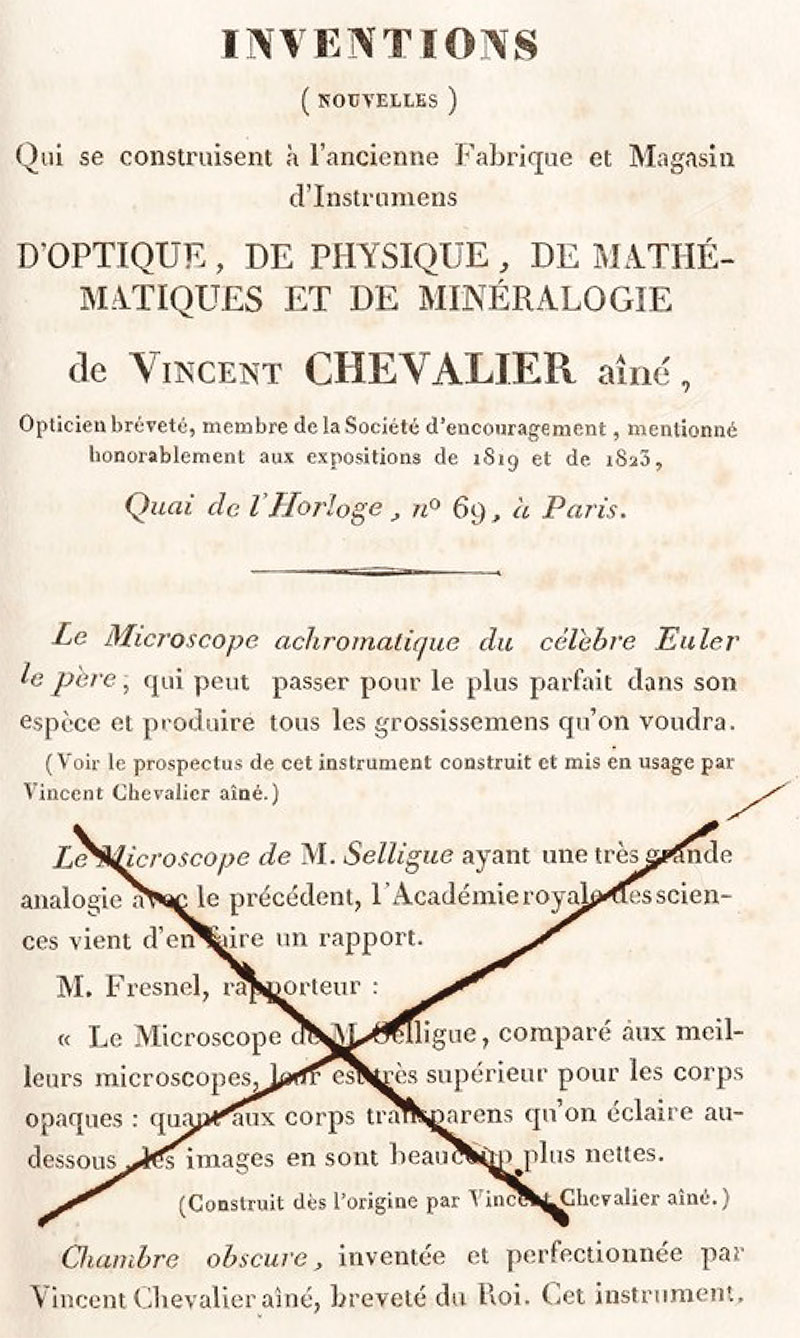

Vincent and Charles Chevalier had realized that a simpler combination, with a different arrangement of three lenses, produced a cleaner achromatic combination (Figures 3, 4 and 63). They revealed their new, achromatic microscope on March 30, 1825. The Chevaliers named this invention the “Euler” microscope, after Leonhard Euler (1707-1783), who had theorized on the composition of achromatic lens combinations. By crediting a long-dead physicist for development of the achromatic microscope, the Chevaliers dismissed the novelty of Selligue’s microscope. Their Selligue-type microscope was soon discontinued (Figure 64).

Thus, Selligue-type microscopes by the Chevaliers can be dated to 1824, and Euler-type instruments to after March, 1825. Vincent evidently continued to make Euler-type microscopes into the 1830s (Figure 8).

Charles Goring (1793-1840), the famous London optical engineer, wrote in 1827, “The curiosity of many will doubtless be excited, as to what our neighbours, the French, ever foremost in the pursuit of glory, both in arts and arms, have been doing in the affair of achromatic object-glasses for microscopes. With the highest satisfaction I find myself enabled to state, that Messieurs Chevalier, (aine et fils,) No. 69, Quai de 1'Horloge, Paris, have rivalled our own artists, in this branch of the manufacture of optical instruments”.

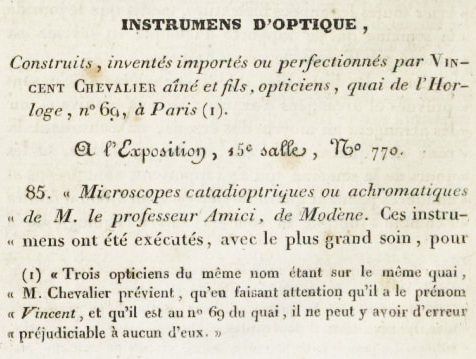

Giovanni Amici undertook an extended trip to Paris and London from 1825 through 1827. He met with the Chevaliers and other optical craftsmen in both cities. Charles Chevalier wrote (1831) that “Mr. Amici abandoned in 1815 his first attempts upon achromatic glasses, because they were not equal to his reflecting microscopes; and it was not till 1824, after the report of M. Fresnel, that the philosopher of Modena undertook this work, by adopting the system of M. Selligue with regard to the superposition of object-glasses. He pursued this idea with great success, for on the 25th May 1827, he brought to France a microscope whose object-glass was composed of three lenses superposed, each having about six lines of foci, and a large aperture, but not cemented. This instrument, united to a great magnifying power, a remarkable distinctness, as well as the horizontality of the instrument, and excited the admiration of both philosophers and amateurs. During the stay of M. Amici at Paris, Vincent and Charles Chevalier exhibited in the Louvre a horizontal microscope, constructed on the principles and after the advice of M. Amici; and this instrument was deemed worthy of the silver medal by the central jury”. Such a microscope is illustrated in Figure 7, above. An 1827 announcement of the Chevaliers’ exhibition entries is shown in Figure 65, below.

In 1829, Charles wrote a booklet on the Chevaliers’ cameras obscuras and cameras lucidas. Charles was the sole author. Moreover, their business was described as “Vincent et C. Chevalier, opticiens” (Figure 66).

As further evidence of Charles Chevalier’s rise in the world, he married Marie Zoé de La Sayette, on February 14, 1829. The record of their marriage notes that the Chevaliers did not live at their shop on Quai de l’Horloge, but instead resided at 16 Place Dauphine. Vincent’s 1841 death record shows that he and his wife lived there until his death. Before her marriage, Marie Zoé had lived nearby, at 24 Place Dauphine. Charles and Marie Zoé’s son, Arthur, was born on March 15, 1830.

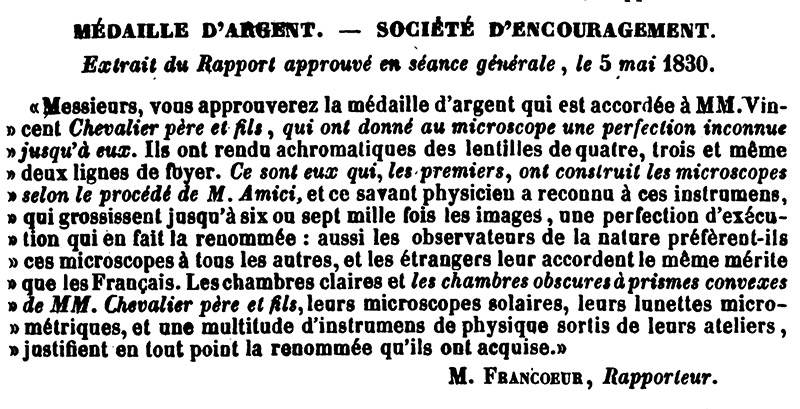

Although later writings by Arthur Chevalier and others give 1830 or 1832 as the date for Charles leaving the partnership with Vincent, Charles himself wrote that the split took place in 1833 (see below). Two further pieces of evidence further support a date after 1830. Vincent and Charles together won a Silver Medal at the 1830 exhibition of the Socièté d’Encouragement pour l'Industrie Nationale (Figure 67). Charles wrote a letter to Charles Goring on the Chevaliers’ achromatic microscopes, dated February 10, 1831, and addressed from 69 Quai de l’Horloge.

According to Charles’ son, Arthur, the split between Vincent and Charles involved money: Charles felt that he was not receiving an adequate share of the partnership’s profits. Vincent would not budge, so Charles moved out and founded his own shop. He decided against a spot near Quai de l’Horloge, where he would be in direct competition with his father. From Arthur, “En passant par le Palais-Royal, il vit un magasin située galerie de Valois, no. 163 ... Il lui fallait aussi des ateliers, il chercha aux alentours, et s’arrêta rue Neuve-des-Bons-Enfants, no. 1, où il resta cinq à six années, transportant ensuite ses ateliers cour des Fontaines, 1 bis, et 3, là ou il devait mourir”. (“Passing through the Palais-Royal, he saw a store located in the Valois gallery, no. 163 ... He also needed workshops, he looked around, and stopped at 1 rue Neuve-des-Bons-Enfants, where he stayed five to six years, then transporting his workshops to 1-3 Cour des Fontaines, until he died”.

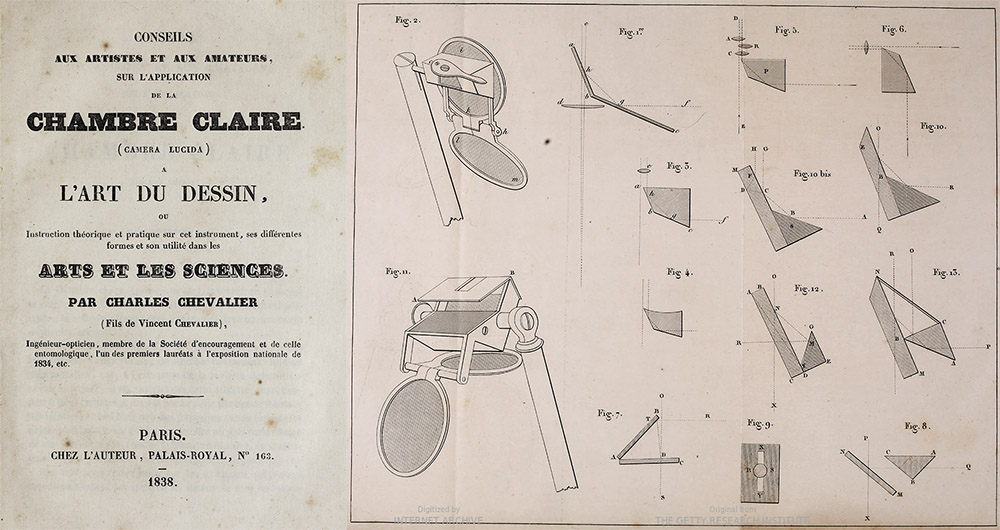

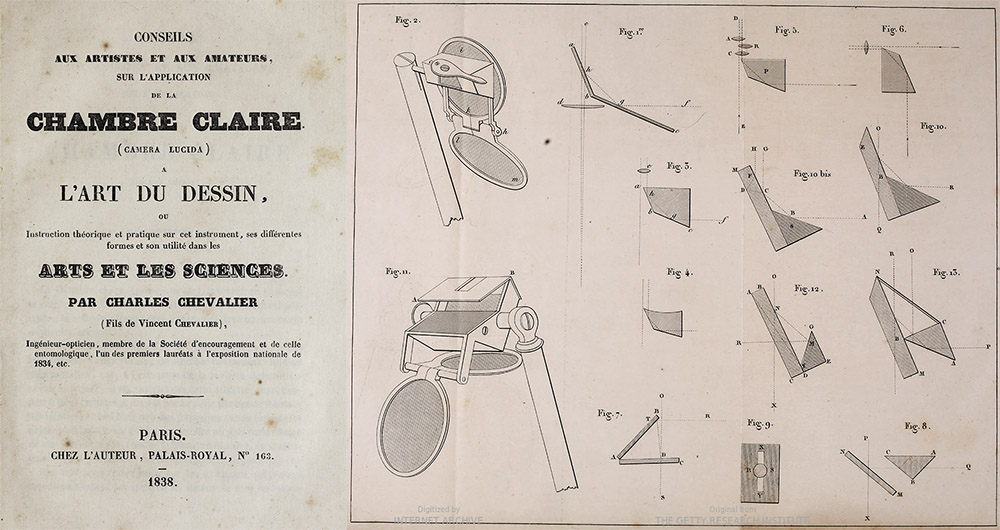

Also in 1833, Charles published a detailed description of his “microscope simple perfectionné” in Annales des Sciences Naturelles, giving his address as 163 Palais Royale (Figures 16 and 17). An advance in microscopy, he used doublet and triplet plano-convex lenses in constructing the eyepieces. This would have been a major announcement to the scientific world of both Charles’ independence and his innovative optical apparatus.

Both Vincent and Charles entered exhibits at the 1834 Exposition des Produits de l’Industrie. Charles won a Gold Medal, while Vincent won a Silver. Entrants described their works in the Notice des Produits de l'Industrie Française.

Charles boasted of a wide variety of optical, scientific, and engineering products, including microscopes: “M. Charles Chevalier; of Paris, Palais-Royale, no. 163, Valois Gallery and rue Neuve-des-Bons-Enfans, no. 1, above Quai de l'Horloge; engineer-optician; member of the Society of Encouragement for the National Industry, of the Physical and Chemical Sciences of Paris and of the Entomological one of France; leading manufacturer in France of achromatic microscopes and of the oxy-hydrogen gas microscope; author of various modifications to these useful instruments, having received jointly with his father, Mr. Vincent Chevalier, a silver medal at the 1827 exhibition, one from the Society of Encouragement in 1830, and another from the Athénée. This skilful optician makes new simple microscopes and magnifiers for botany, adopted by several learned professors; light chambers with new modifications, and dark chambers with a meniscus prism with explanatory note, advanced phantasmagoria, very portable barometers for the measurement of heights, telescopes for the navy, astronomy and travel; Borda and Sextant circles, new micrometric glasses for distances, mathematical cassettes, squares, graphometers, circles and other geodetic instruments; electro-magnetic instruments, diagometers and galvanometers, polarization devices and all the machines that make up a physics cabinet. He also offers an assortment of the most fashionable eyeglasses and opera glasses and all kinds of thin glasses to keep your eyesight”.

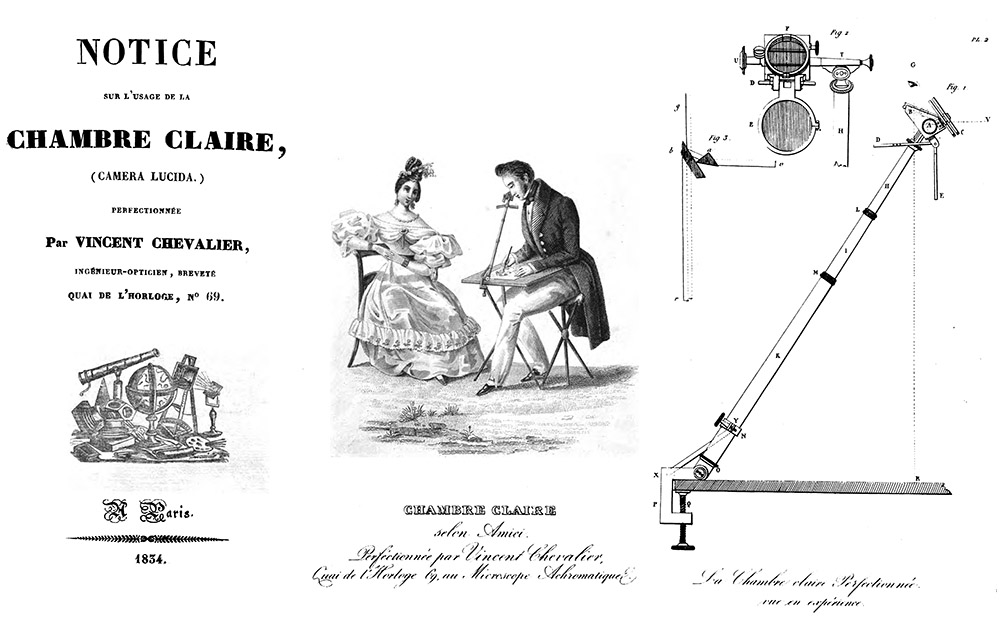

Vincent published a booklet on his camera lucida in 1834 (Figure 68). He noted that it was based on the design of Battista Amici, for which he had received acclaim in 1820 (see above). The rear of the booklet listed other optical items that could be obtained from Vincent Chevalier: “microscope achromatique” as described in 1824 (presumably his Euler model), an achromatic solar microscope, and a chamber obscura.

Charles published a book on his version of the camera lucida in 1838 (Figure 69).

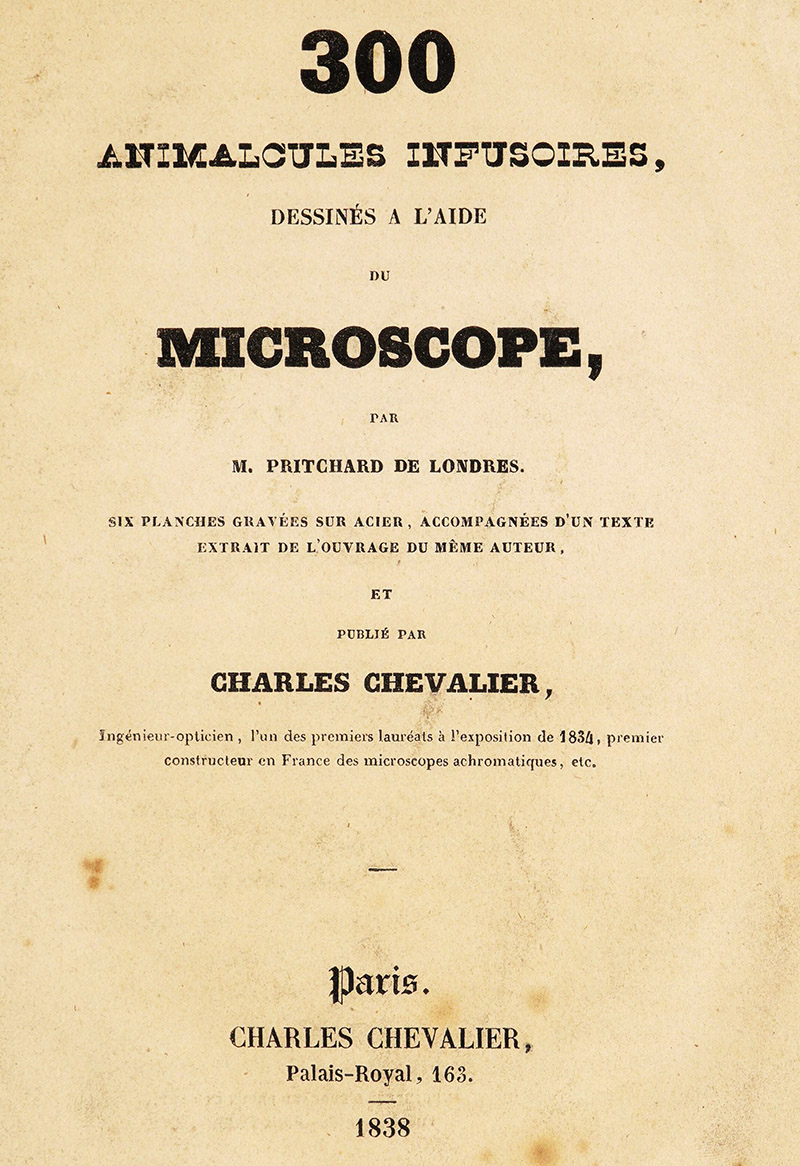

In that same year, Charles Chevalier also published a French adaptation of Andrew Pritchard’s popular Natural History of Animalcules, as 300 Animalcules Infusoires Dessinés a l’Aide du Microscope (Figure 70). Charles described himself as “Ingénieur-opticien, l’un des premiers lauréats à l’exposition de 1834, premier constructeur en France des microscopes achromatiques, etc.”

Charles published Des Microscopes et de Leur Usage in 1839. This book provided details on how microscopes work and their uses. Two large, fold-out plates illustrated Charles Chevalier’s microscopes of that time (Figures 19 and 20, above). He provided a detailed description of his new Grand Universal Achromatic microscope (Figure 22, above), although he barely mentioned any of his other models. Here, we also find Charles statement of when he left his father: “En 1833, je séparai mon établissement de celui de mon père” (“In 1833, I separated my establishment from that of my father”) (page 90).

In 1840, one of Charles Chevalier’s workmen, Camille Nachet (1799-1881), left to start his own optical business. Jules Pelletan later wrote, “C.S. Nachet avait succédé, dans l'optique française, à Ch. Chevalier, son maître, chez qui il était entré en 1834, au moment de la plus grande gloire de celui-ci, et à qui, pendant six ans, il apporta un concours utile et apprécié. En 1840, il s'établit à son compte, et se consacrant exclusivement à la construction des microscopes, il fonda une maison qui fut, pendant un temps, la plus connue de toute l'Europe”. (“C.S. Nachet was the successor, from the French point of view, to Ch. Chevalier, his master, with whom he had entered in 1834, at the time of his greatest glory, and to whom, for six years, he provided useful and appreciated assistance. He established his own business in 1840 and, devoting himself exclusively to the construction of microscopes, he founded a house that was, for a time, the best known in all of Europe.”).

Vincent Chevalier died on November 29, 1841. From a record of the settlement of his estate, we learn that Vincent and his wife, Marie Madeleine Wagener, had two sons: Charles, and Jean-Baptiste Nicolas Chevalier, a “vérificateur en bâtiments” (“building auditor”), who lived at 42 Rue du Dragon. Some authors have suggested that Charles moved back to his father’s shop at the time of Vincent’s death, but neither this record nor any other contemporary source shows Charles anywhere except Palais Royale. Vincent’s estate was valued at 30199 Francs. An employee of Vincent’s, Pierre Ambroise Richebourg, was an official witness to the appraisal. Richebourg acquired Vincent’s shop at 69 Quai de l’Horloge, and probably items from the estate, thereby opening his own optical business. An illustrated history of Richebourg is forthcoming on this site.

During 1848, the name of Charles’ business complex was changed from Palais Royale to Palais National. The next year, in 1849, Chevalier moved his shop from number 163 to 158 (Figure 73). The building’s name reverted to Palais Royale in 1852. Those address changes help date Chevalier’s apparatus.

Arthur, Charles son, married Marie Eugénie Bernage on 29 November, 1855. Their marriage contract gave his occupation as “employé opticien” (“employee optician”), indicating that he worked for his father, and was not a partner. Arthur lived with his father and mother at 3 Passage de la Cour-des-Fontaines.

Two of the largest optical shops in Paris were those of Chevalier and Chevallier, whose similar names often led to confusion. J.G.A. Chevallier (2 “LL”s) was widely known by the nickname “l’Ingenieur Chevallier”, and, after he died in 1848, his successor named the business “Maison de l’Ingenieur Chevallier”. Meanwhile, since he considered himself to be an optical engineer, Charles Chevalier took to calling himself “l’Ingeneur Chevalier”. In 1857, Victor Ducray-Chevallier, J.G.A. Chevallier’s son-in-law and the owner of “Maison de l’Ingenieur Chevallier”, filed suit against Charles Chevalier. The court ruled in favor of Ducray-Chevallier. Charles was ordered to pay Ducray-Chevallier’s legal costs, plus pay to have announcements of the judgement published in newspapers. A detailed account of this legal case is presented in the microscopist.net essay on J.G.A. Chevallier and Victor Ducray-Chevallier.

Charles Chevalier died on November 21, 1859. The estate was divided between his widow, Marie Zoé, son Arthur, and daughter Marie Joséphine Gabrielle (who was married to a florist named Louis Auguste Nicolas Chagot). On July 30, 1860, Arthur and his mother entered into a formal partnership to jointly operate a “société ayant pour objet la fabrication et la vente d'instruments d'optique de toute nature et d'appareils photographiques” (“company whose purpose is the manufacture and sale of optical instruments of all kinds and cameras”).

The Chevalier business had evidently suffered during the last years of Charles’ life. Henri van Heurck wrote in his 1869 edition of The Microscope, “Arthur Chevalier … a succédé à son père, à qui le microscope, outre les lentilles achromatiques a court foyer, doit tant d’importants perfectionnements. Il a repris avec beaucoup d’ardeur et de succès la construction des instruments de micrographie dont la fabrication avait été négligée par son père dans les dernières années de sa vie, par suite du mauvais état de sa vue” (“Arthur Chevalier … succeeded his father, to whom the microscope, in addition to achromatic short-focus lenses, owes so many important improvements. He resumed with great ardor and success the construction of micrographic instruments, the manufacture of which had been neglected by his father in the last years of his life, due to the poor state of his eyesight”). van Heurck expanded on this in his 1893 edition of The Microscope: “Dr. Arthur Chevalier … after a desperate struggle, he succeeded in resuscitating, financially speaking, the firm which his father, a man of research, and an inventor, but not a man of business, had left in difficulty”.

Operating under the name of Arthur Chevalier, the new business promptly issued new catalogues in many fields. Catalogues included lists of the Chevaliers’ awards, with the most recent having been a First Class Medal at the 1855 Paris Universal Exposition, indicating that Charles Chevalier’s neglect did not have a severe impact on quality (Figure 78).

During the early 1860s, Arthur also published several books on his products and predecessor. His 1862 “Étude sur la Vie et les Travaux Scientifiques de Charles Chevalier, Ingeneur-Opticien” provided numerous details on his father, along with numerous letters from optical experts to the father and son. Others included Hygiène de la Vue (“care of eyesight”, 1861), Photographie (1861), and La Méthodes des Portraits Grandeur Naturelle et des Agrandissements (1862).

Arthur published an important historical work in 1864: his first edition of L’Etudiant Micrographe, (“The Student Microscopist”). This book included numerous engravings of Chevalier’s different microscopes, along with explanations of microscopical techniques and theory (Figure 36, above).

A second edition of L’Etudiant Micrographe was published one year later, in 1865. Thoroughly revised, this edition included pictures of many new models of microscopes, and apparent discontinuation of some old ones (Figure 37, above).

Arthur was awarded an honorary doctoral degree from the University of Rostock in 1870. From that time onward, he referred to himself as “Doctor”, and engraved his microscopes thusly. Arthur Chevalier’s apparatus can be dated as pre- or post-1870 by the absence or presence of “Doctor”, respectively.

Arthur Chevalier’s health was in decline, and his company evidently began to falter. Heinrich Frey’s 1872 textbook The Microscope and Microscopical Technology stated, “The older firm of Chevalier has recently taken a new start, through the son, Arthur Chevalier (Palais Royal, No. 158). A competent judge, von Heurck, has recently given prominence to Chevalier's optical productions. Unfortunately, I have not as yet seen anything from this establishment”. It is significant that a microscopist of Frey’s stature was not familiar with Arthur Chevalier’s products twelve years after he assume control of the Chevalier firm.

Arthur Chevalier died on January 9, 1874. He was only 43 years old at the time of his death. As mentioned above, his early demise, and that of his immediate family, suggest tuberculosis as the cause.

Jules Pelletan later wrote, “The house that was founded by Vincent and Charles Chevalier, father and son, does not exist today. After the death of Charles Chevalier, it was passed into the hands of his son Arthur. It was not long in losing its former significance under the direction of this good, but sick man, who lacked, moreover, the necessary skills to succeed his skillful and learned father. Although Dr. Arthur Chevalier did his best to imitate the instruments of MM. Nachet, he was never able to restore the former lustre to his house, and it was only his universally known name, his advantageous location in the galleries of the Palais-Royal, and the sale of glasses, spyglasses, and eyeglasses that saved him from ruin”.

A record of Arthur’s estate listed his heirs, “sa veuve, Marie Eugénie Bernage, fabricante d'instruments d'optique, … légale de leurs trois filles mineures, Adèle Marie Gabrielle, Marie Louise Charlotte et Marie Simone Jacqueline Chevalier” (“his widow, Marie Eugénie Bernage, manufacturer of optical instruments, … legal guardian of their three minor daughters, Adèle Marie Gabrielle, Marie Louise Charlotte and Marie Simone Jacqueline Chevalier”). It included “jumelles, longues vues, verres de lunette, pince-nez, microscopes, baromètres, thermomètres, compas, loupes, boussoles, instruments de chirurgie, appareils de pesée, de géodésie, de physique” (“binoculars, telescopes, glasses, pince-nez, microscopes, barometers, thermometers, compasses, magnifiers, compasses, surgical instruments, weighing apparatus, geodesy, physics”). Two Parisian opticians, Charles Denis Adelle Avizard and Charles Eugène Videpied, were appointed to evaluate Arthur Chevalier’s estate, arriving at a value of 25838 Francs.

Daughter Marie Simone Jacqueline Chevalier died a little over a month after her father, on February 26, 1874.

Arthur’s widow, Marie Eugénie Bernage Chevalier, also died on February 26, 1874. Ownership of the Chevalier optical business and the rest of her estate went to the two remaining daughters, Adèle Marie Gabrielle and Marie Louise Charlotte. A manager was brought in to take care of the business for the young girls.

Pelletan wrote that the firm tried to hide Arthur’s death from their customers, a reasonable approach for a business that did not have a head. He described the heirs as “two young and charming girls, almost children”.

In 1878, “Chevalier (A.), à Paris, galerie de Valois, 158” exhibited microscopes and ophthalmoscopes at the Exposition Universalle International

Marie Louise Charlotte Chevalier died on July 24, 1880. Her sister, Adèle Marie Gabrielle, evidently died earlier, and the Chevalier business was soon sold out of the family.

The sale was completed in 1881. An accountant’s record reads, “Cahier des charges pour la vente d'un fonds d'opticien désigné sous la raison sociale, Maison du Docteur Arthur Chevalier, situé 158, galerie de Valois au Palais-Royal à Paris, dépendant de la succession de Marie Louise Charlotte Chevalier, à la requête de ses héritiers. La mise à prix est fixée à 25 000 Francs. À signaler: l'acte comprend un cahier de 19 feuillets, clos à la date du 23 avril 1881, dressant le détail du mobilier et du matériel industriel du fonds estimés à 42 103,34 francs” (“Specifications for the sale of an optician fund designated under the name, House of Dr. Arthur Chevalier, located 158, Valois Gallery at the Palais Royal in Paris, dependent on the succession of Marie Louise Charlotte Chevalier, at the request of her heirs. The price is set at 25,000 Francs. Note: the estate includes a notebook of 19 sheets, closed on April 23, 1881, detailing the furniture and industrial equipment of the fund estimated at 42,103.34 francs”).

Charles Avizard and his brother, René, continued to operate Maison du Docteur Arthur Chevalier at 158 Palais Royale, separate from their other optical shop at 57 Rue Rambuteau. Two years later, in early 1883, the Avizard brothers purchased the business of Maison de l’Ingénieur Chevallier from Victor Ducray-Chevallier’s widow (Figure 75). All three shops were maintained until 1900, when the Avizards merged their original shop with that of Maison de l’Ingénieur Chevallier. At some point between 1914 and 1921, the Avizards merged the Chevalier and Chevallier enterprises, and relocated to 27 Avenue de l’Opéra (Figure 76). I did not find information on when it terminated.

Henri van Heurk, who had been a friend of Arthur Chevalier’s summed the up the Chevalier business from 1859 onward, in his 1893 edition of The Microscope:

“Dr. Arthur Chevalier (Palais Royal, Paris) - We only mention the firm of Chevalier as being historically noted in optics. Our excellent friend, Dr. Arthur Chevalier, died shortly after the war of 1870-71, when, after a desperate struggle, he succeeded in resuscitating, financially speaking, the firm which his father, a man of research, and an inventor, but not a man of business, had left in difficulty. The most hopeful future offered itself to him, but, alas, neither he nor his have obtained any profit from it. Madame A. Chevalier and her two (sic) daughters followed him to the grave at an interval of a few years. Only strangers inherited the result of the difficult work of poor Arthur, and the house put up to sale was bought for £6,000 by M. Avizard, who is still its present proprietor. We have not examined the instruments of this firm since M. Avizard took possession. The stands are still such as we described them in 1878, but we do not know if the objectives have undergone any improvement. Arthur Chevalier was a high-minded man and well read, not only in microscopy, but also in all natural and medical science. If fortune had smiled on him at an opportune moment, and had he lived for a few years longer, he would probably have effected a substantial progress in microscopy”.

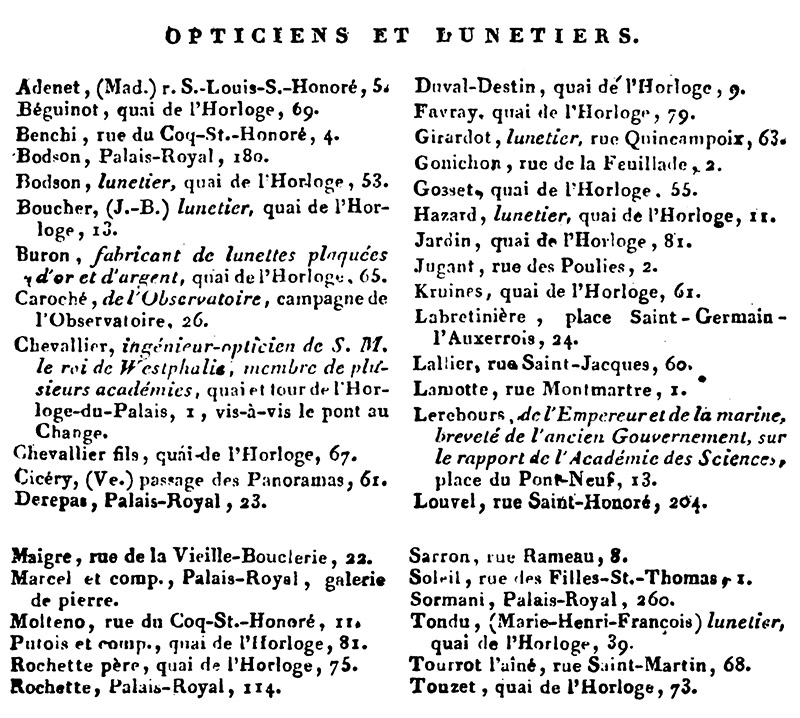

Figure 61.

1809 listing of opticians and eyeglass-makers, from “Almanach du commerce de Paris”. Vincent Chevalier is noted as “Chevalier fils”. This was the first year that the Chevalier business was listed in the “Almanch”.

Figure 62.

Cover of Augustin Fresnel’s 1824 report to the l’Académe Royale des Sciences on ‘le microscope achromatique de M. Selligue”.

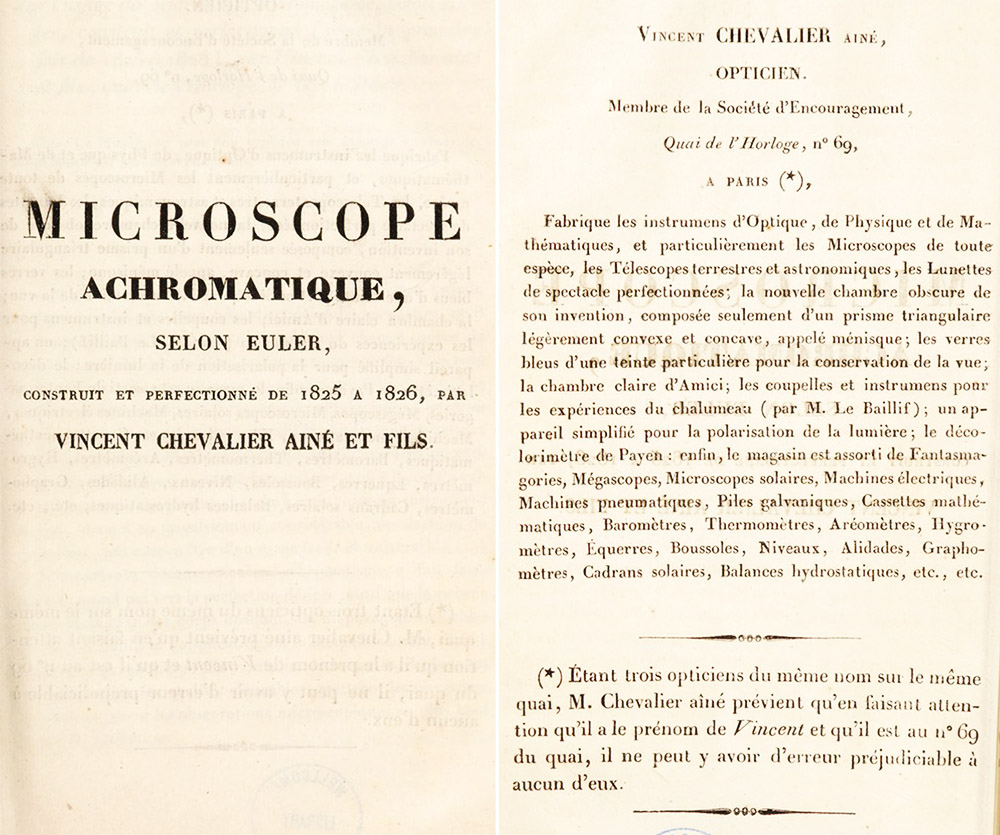

Figure 63.

Cover and inside of an 1826 description of “microscope achromatique, selon Euler”, by Vincent Chevalier ainé et fils. The footnote points out that there were then three optical businesses of with similar names on Quai de l’Horloge: in addition to that of J.G.A. Chevallier (“l’Ingénieur Chevallier”), a Jean Louis Joseph Chevalier had an optical shop at 65 Quai de l'Horloge, four doors from Vincent and Charles.

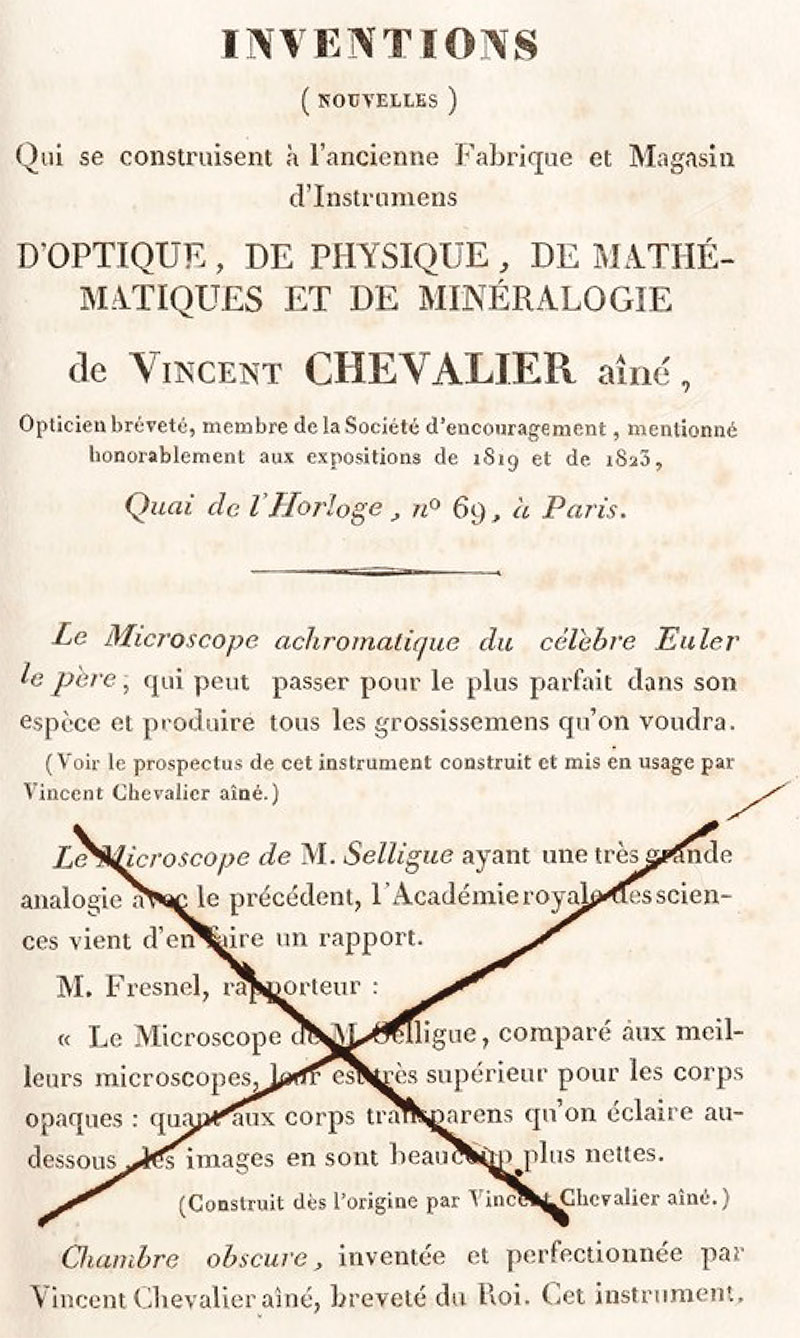

Figure 64.

Excerpt from a ca. 1826 Chevalier catalogue, with the Selligue-type microscope crossed out.

Figure 65.

Description of Vincent and Charles Chevalier’s entries in the 1827 Exposition des Produits de l’Industrie, which included a catadioptric (i.e. mirrored) and achromatic microscope in the style of Giovanni Amici. They were awarded a Silver Medal for their entries.

Figure 66.

Cover of an 1829 booklet on chambers obscuras and chambers claires (i.e. cameras lucidas), written by Charles Chevalier, and published by Vincent and Charles Chevalier. It is doubly notable that Charles wrote this booklet without his father, and the business was now known by both of their names.

Figure 67.

Note by Charles Chevalier on the Silver Medal that he and his father won together on May 5, 1830. From Charles’ 1839 French edition of Andrew Pritchard’s “300 Animalcules Infusoires, Dessinés à l'Aide du Microscope”.

Figure 68.

In 1834, Vincent Chevalier published a new edition of the booklet on his Amici-type camera lucida drawing device. Shown here are the cover page, frontispiece, and diagram of the instrument. He was then 63 years old, so the illustrated characters were probably based on hired models.

Figure 69.

Cover page and technical diagram from Charles Chevalier’s 1838 book on his camera lucida. The volume also included an engraving of a man (probably Chevalier) using the instrument, which is shown above in Figure 14.

Figure 70.

Cover of Charles Chevalier’s 1838 French-language adaptation of Andrew Pritchard’s “Natural History of Animalcules”.

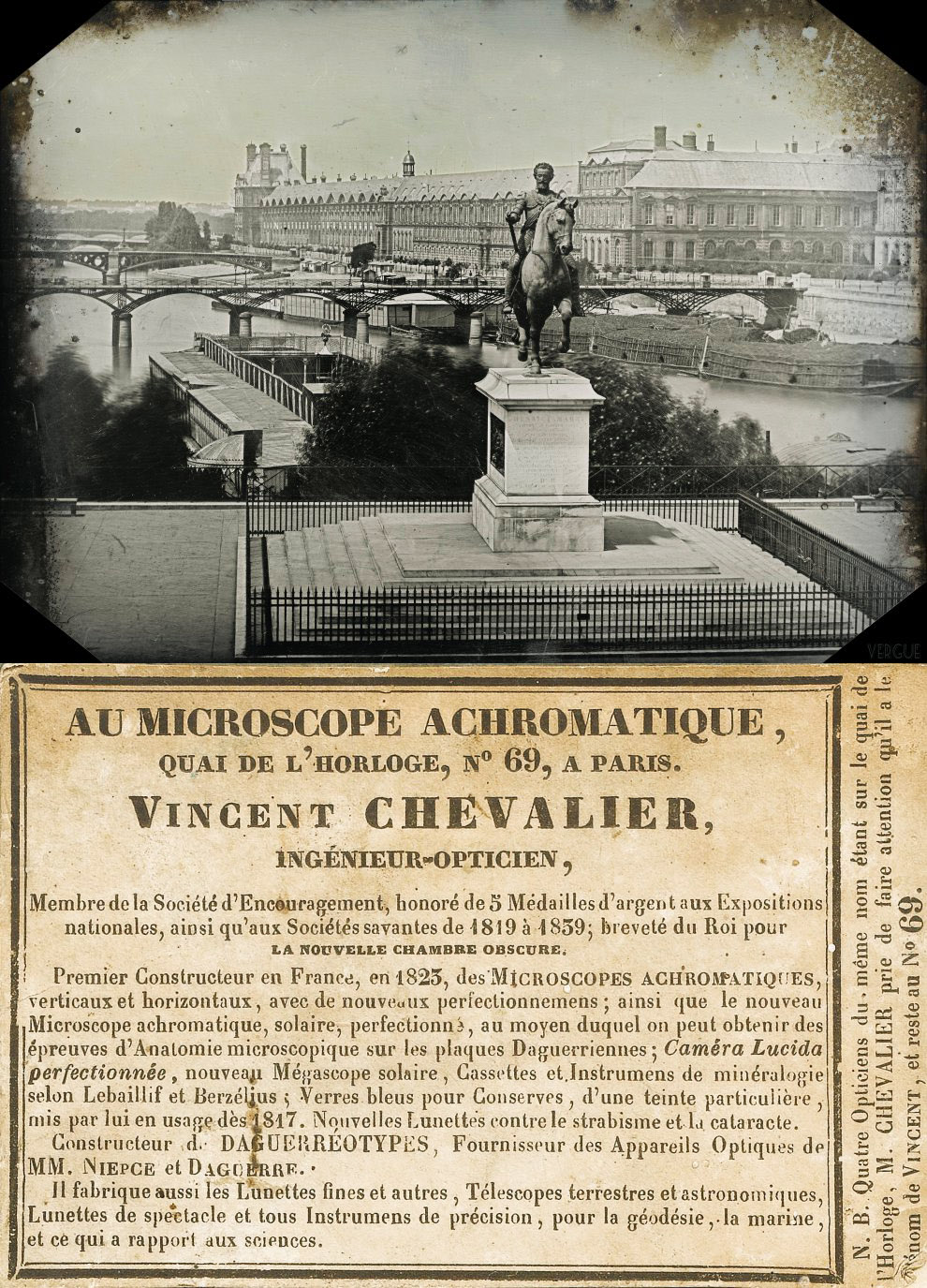

Figure 71.

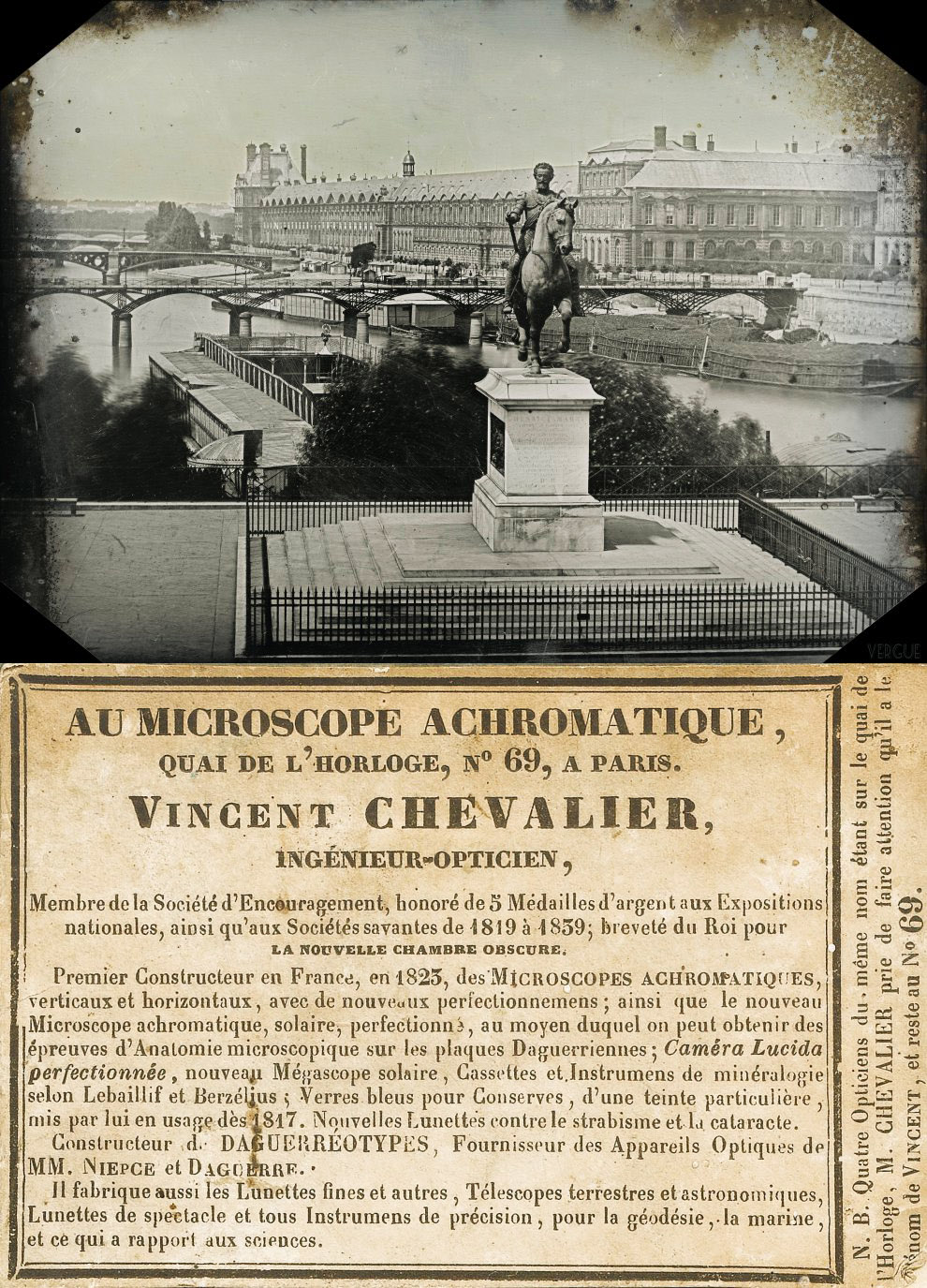

Circa 1840 daguerreotype photograph of the statue of King Henri IV at Pont Neuf, Paris, retailed by Vincent Chevalier. The lower image shows Vincent’s advertisement that is on the back of the photograph. The advertisement mentions Vincent’s 1839 Silver Medal. He might have been the photographer. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from http://vergue.com/post/313/Henri-IV-et-la-Seine.

Figure 72.

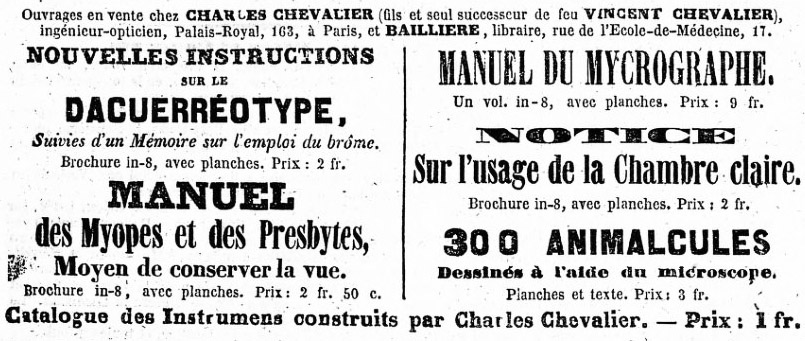

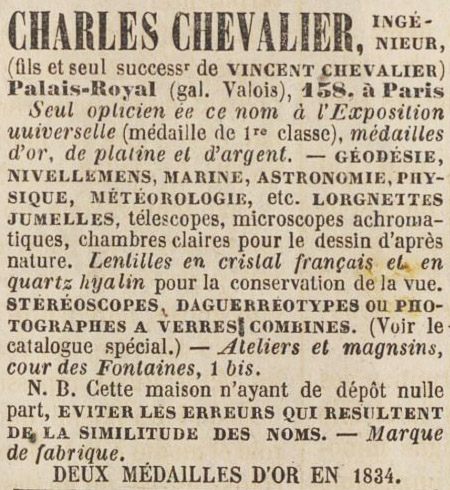

An 1842 advertisement, from “La Presse”.

Figure 73.

An advertisement from the 1851 “Almanach National Annuaire de la République Français”. The building that housed Chevalier’s shop changed its name from Palais Royale to Palais National in 1848, and he moved to another space, number 158, in 1849. The building’s name reverted to Palais Royale in 1852.

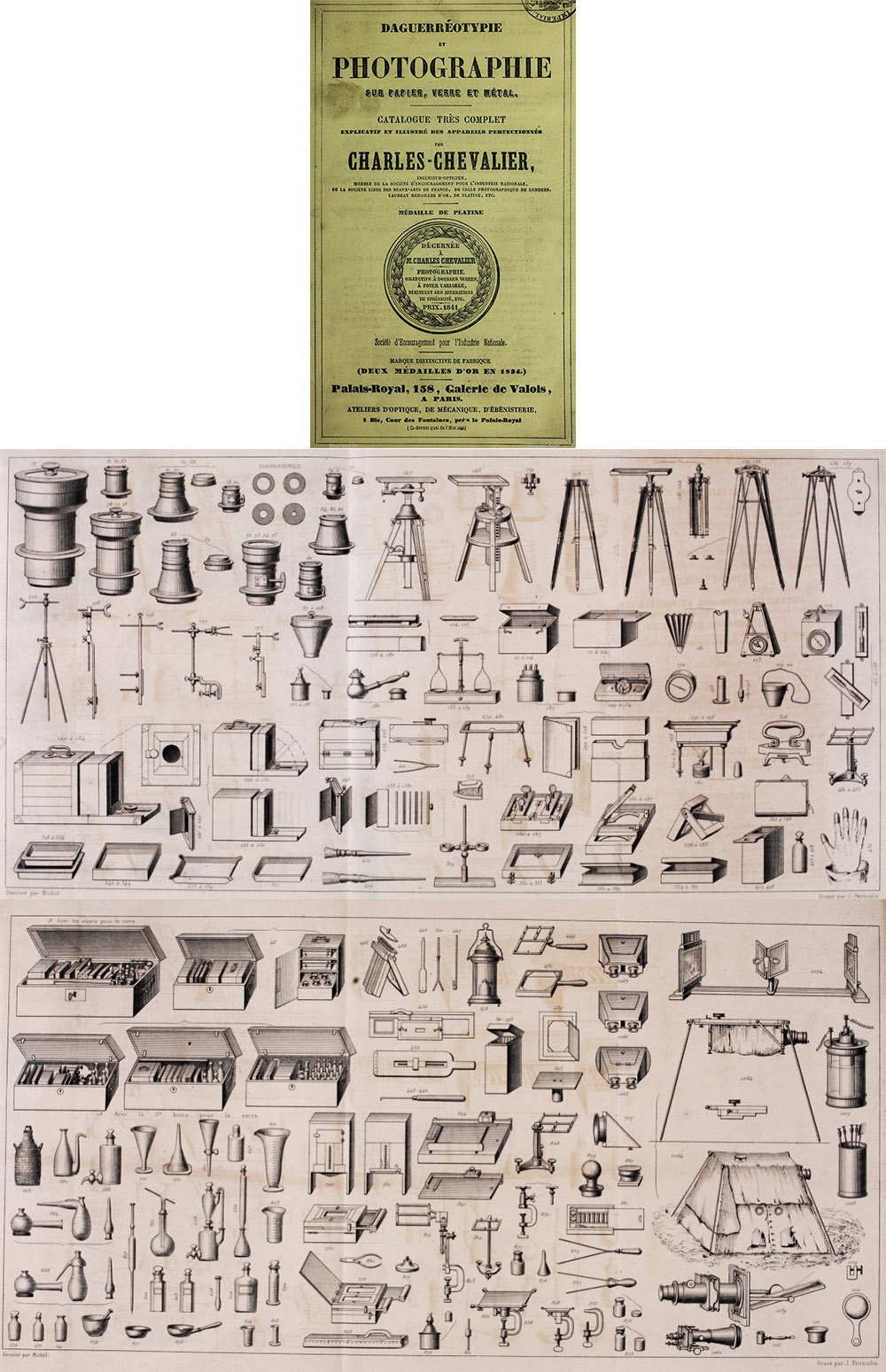

Figure 74.

Cover and two fold-out pages of Charles Chevalier’s catalogue of photographic equipment, circa 1852.

Figure 75.

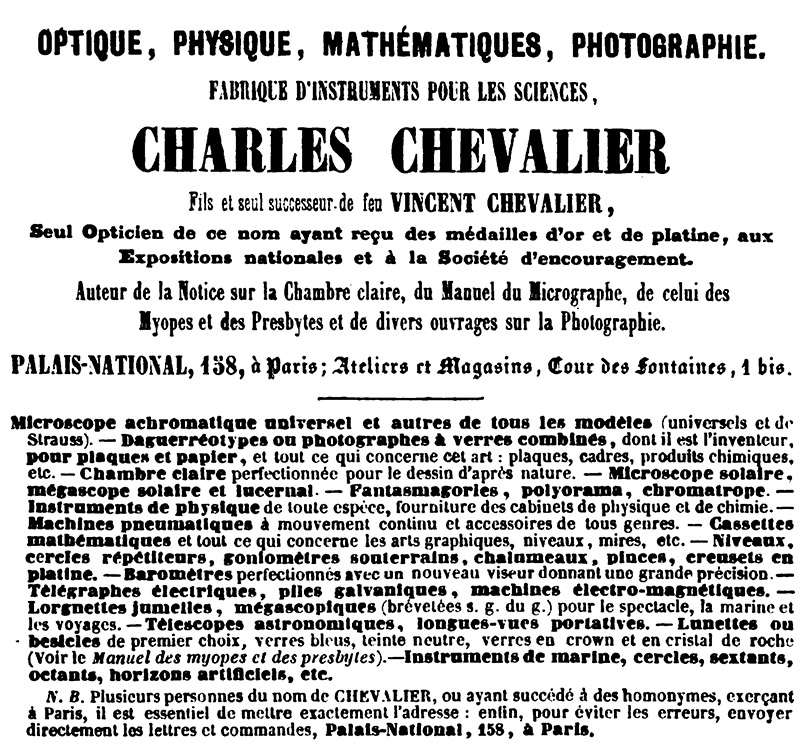

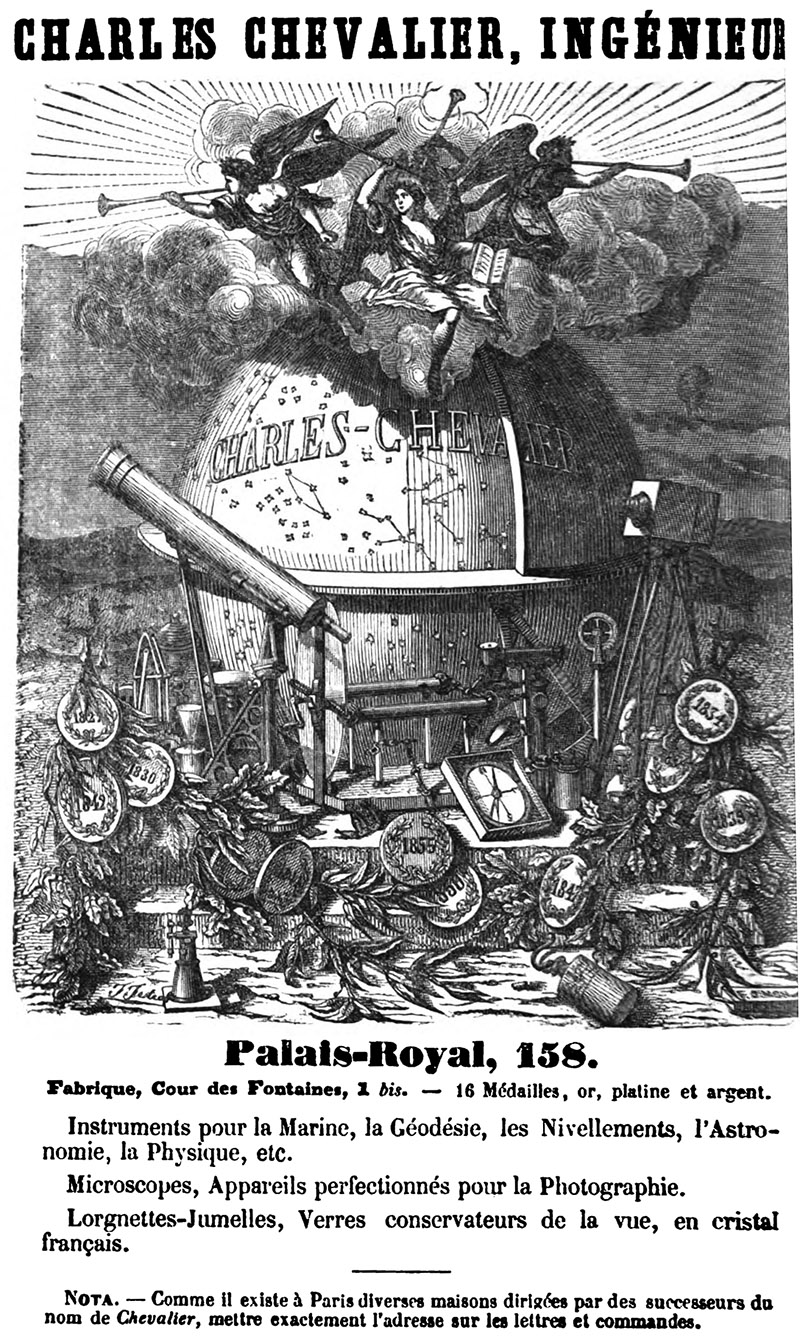

An 1856 Charles Chevalier advertisement, from “Le Nouvelliste”

Figure 76.

An 1858 advertisement, from “Le Chivari”.

Figure 77.

An 1859 advertisement, from “Almanach Impérial”.

Figure 78.

Excerpts from Arthur Chevalier’s 1860 catalogue of meteorological apparatus. The page on the left gives a chronology of the Chevalier business, although most of the dates are incorrect. Accurate dates, based on numerous contemporary sources and to the best of my knowledge, are listed in the text above. These are: founding of the business by Louis Vincent Chevalier occurred in 1865, Jacques Vincent took over the business after his father’s death in 1805, and Charles left his father’s business in 1833. Note also that the “House of Charles Chevalier” omits Vincent Chevalier’s solo business after Charles quit the partnership. The page on the right lists awards to Charles and his father, including prizes won by Vincent after Charles’ departure.

Figure 79.

An 1863 advertisement from “Revue de Thérapeutique Medico-Chirurgicale”.

Figure 80.

An 1870 advertisement, from “Annuaire de Thérapeutique, de Matière Médicale, de Pharmacie et de Toxicologie”. Lacking the honorific “Dr.”, this predated Arthur being awarded an honorary doctorate degree from the University of Rostock.

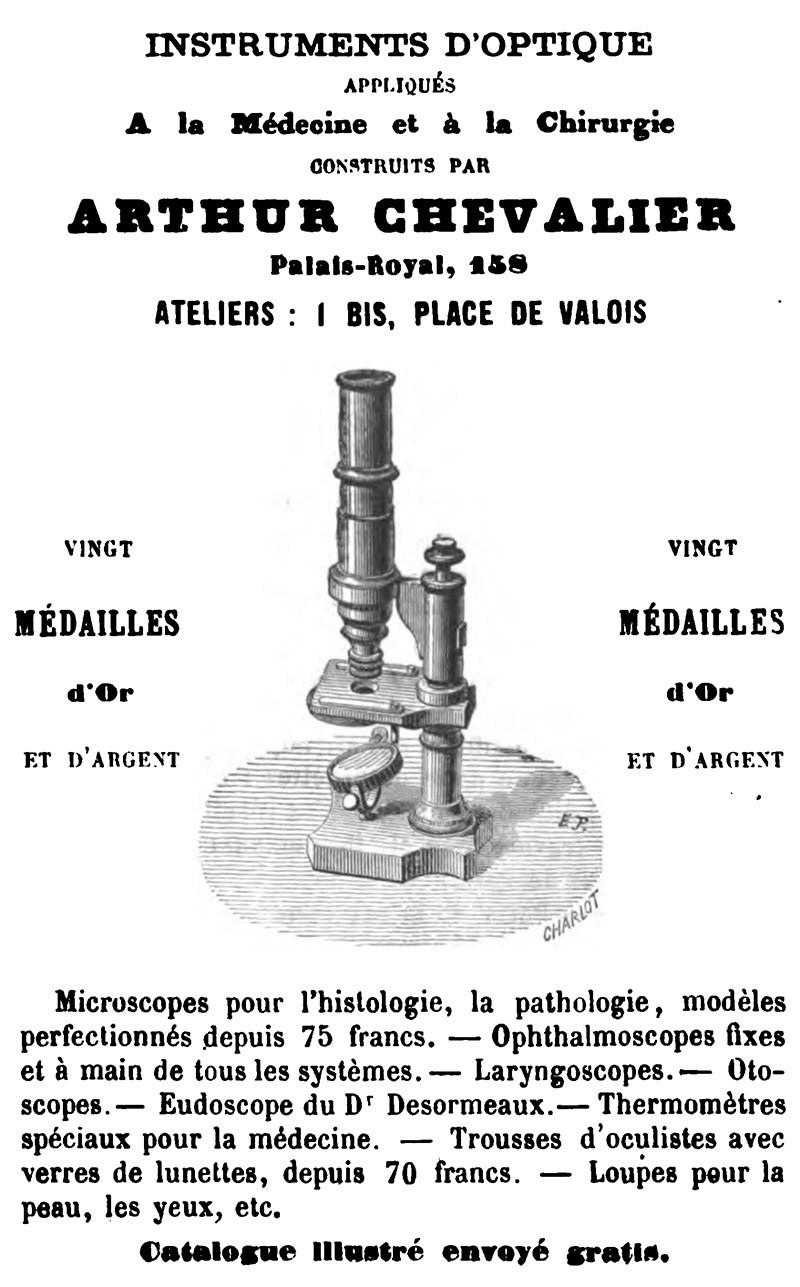

Figure 81.

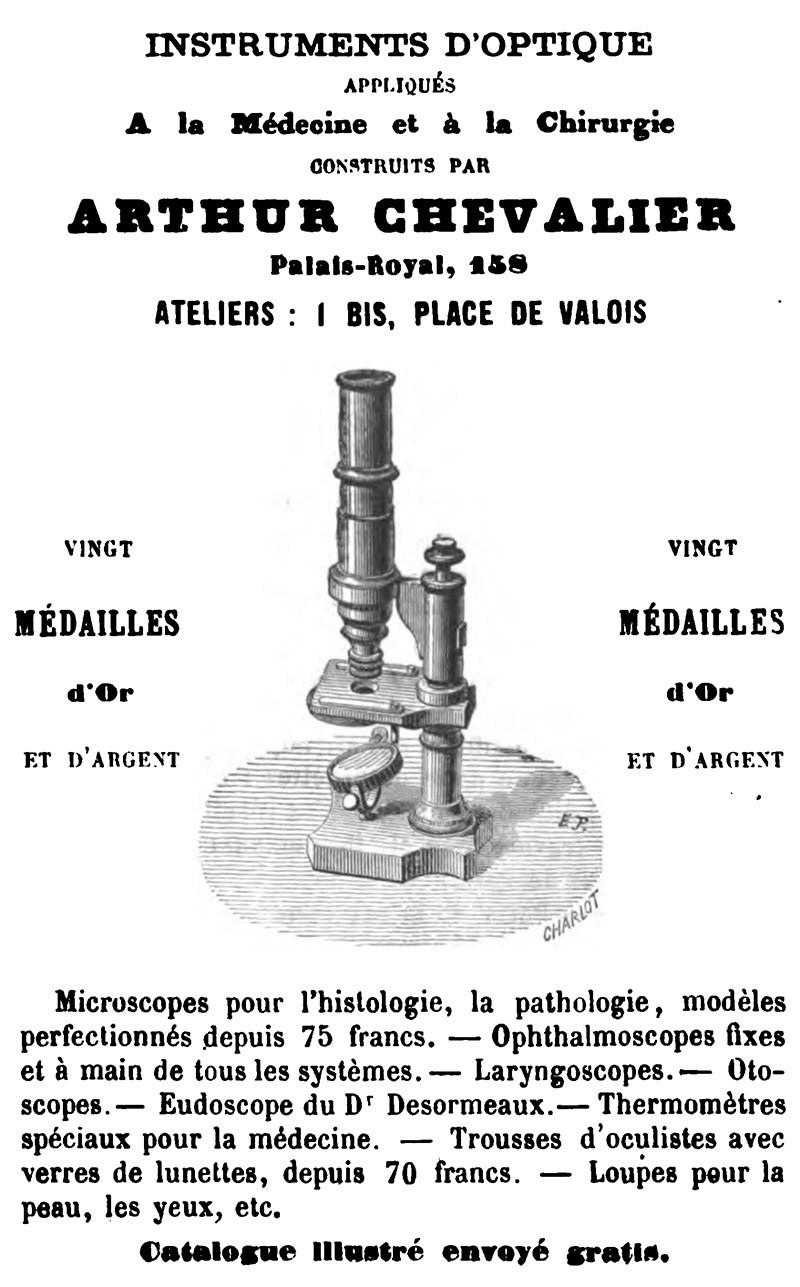

An 1872 advertisement from Dr. Arthur Chevalier, illustrating two of his current microscope models. From “L'Officine, ou, Répertoire Général de Pharmacie Pratique”.

Figure 82.

1880 advertisement, from “Journal de Micrographie”. Arthur had been dead for 6 years, and the firm was owned by his two young daughters.

Figure 83.

An advertisement from 1882, one year after the Avizard brothers had purchased the Chevalier business. From “Bradshaw's Illustrated Travellers' Hand Book to France”.

Figure 84.

Excerpt from the 1891 Annuaire-Almanach du Commerce, de l'Industrie, de la Magistrature et de l'Administration, showing listings for Dr. A. Chevalier and l’Ingéneur Chevallier, both of which were owned by the Avizard brothers. The list also shows information on the business formerly owned by J.G.A. Chevallier’s son, P.M.A. Chevallier, which was at that time owned by Adélaïde Queslin, as well as two minor opticians surnamed “Chevalier”.

Figure 85.

Listing from the 1922 “Annuaire-Almanach du Commerce, de l'Industrie, de la Magistrature et de l'Administration”, showing the merging of Maison du Dr. Chevalier with Maison de l’Ingéneur Chevallier. The owners described this as a “reunion”, although the two houses were begun by two unrelated men, and the two businesses had previously been fierce competitors. Note that the owners misspelled the surname “Chevalier”.

Figure 86.

1887 advertisement from H. Bouquette et Fils, 9 Rue Rollin, Paris, with an illustration of a microscope that is identical to the Arthur Chevalier-signed microscope shown in Figure 56, above. Bouquette was credited for producing microscope bodies for Arthur Chevalier and his successors, and acknowledged for manufacturing the same instruments under his name after Arthur’s death.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Albert Balasse, Yuval Goren, Bjoern Kambeck, Jeroen Meeusen, Jean Paul Mirrione, Jeff Silverman, Barry Sobel, Allan Wissner, and Joe Zeligs for helpful discussions and for permission to use images from their collections.

Resources

Almanach du Commerce de Paris (1798) Lunettiers, page 238

Almanach du Commerce de Paris (1800) Opticiens, page 252

Almanach du Commerce de Paris (1806) Opticiens et Lunettiers, page 223

Almanach du Commerce de Paris (1809) “Chevalier fils, quai de l’Horloge, 67”, page 240

Almanach du Commerce de Paris (1813) “Chevalier, quai de l’Horloge, 67”, page 283

Almanach du Commerce de Paris (1817) “Chevalier”, page 284

Almanach du Commerce de Paris (1820) “Chevalier (Vincent) aîné, ingénieur-opticien, quai de l’Horloge, 69”

Almanach Imperial (1858) Advertisement from Charles Chevalier

Almanach National Annuaire de la République Français (1851) Advertisement from Charles Chevalier

Annuaire du Commerce (1922) pages 2975

Annuaire de Thérapeutique, de Matière Médicale, de Pharmacie et de Toxicologie (1870) Advertisement from Arthur Chevalier, Vol. 25, page 69

Le Belgique Judiciaire (1857) Ducray-Chevallier c. Charles Chevalier, pages 767-768

Bradshaw, George (1882) Bradshaw's Illustrated Hand-Book to France, Advertisement from Arthur Chevalier

Bulletin de la Société d'Encouragement pour l'Industrie Nationale (1820) Rapport fait par M. Hachette, au nom d'une Commission spéciale, sur un prisme convexe de chambre obscure, présenté par M. Vincent Chevalier aîné, opticien, quai de l'Horloge , no. 69, à Paris, page 6

Bulletin de la Société d'Encouragement pour l'Industrie Nationale (1825) On distingue deux espèces de microscopes, pages 240-246