Prudent René Patrice Dagron, 1819 - 1900

by Brian Stevenson

last updated January, 2025

Dagron is best known today for two important developments in microphotography: invention of microphotographs mounted permanently onto small lenses, which were then mounted inside charms, rings, etc, and are commonly known as “Stanhopes”; and production of microphotographic images on collodion films that can be read with use of a lantern projector, which led to the use of microfilms for data storage. Dagron developed the microfilm technique for use during the 1870-71 Franco-Prussian War, for transporting information via carrier pigeons (known as the "Pigeon Post").

Although Dagron patented the “Stanhope” process, it was soon revoked by the French government, and many other people produced similar items. “Stanhopes” with Dagron’s name are quite scarce, even though his company produced thousands of them daily, suggesting that he did not put his name on all of his products. Pigeon Post microfilms are not common, and tend to garner high prices at auctions.

Figure 1.

Dagron initially became famous because of his adaptation of microphotographs to include a built-in “Stanhope”-type magnifying lens, which was usually mounted into a ring, charm, or other piece of jewelry. One did not need a separate microscope, as with the slide-mounted microphotographs of John B. Dancer, John C. Stovin, Alfred Reeves, or other such slide-makers. These three examples may or may not have been produced by Dagron. Images adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from various internet sites.

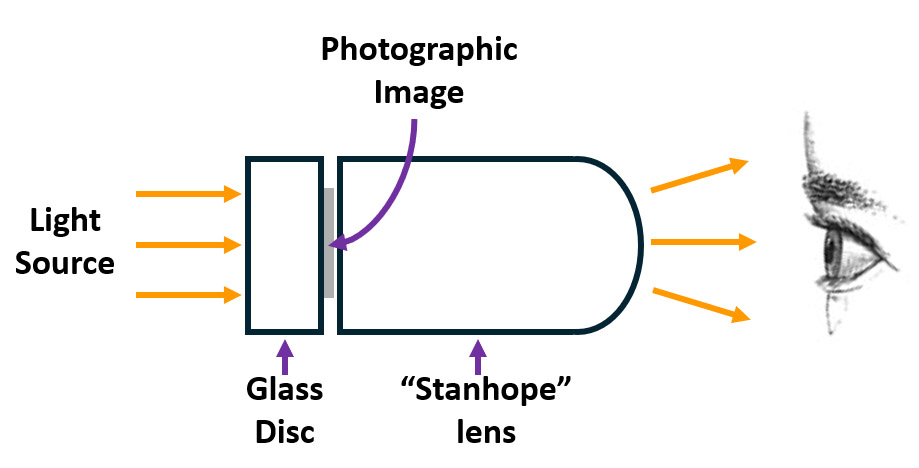

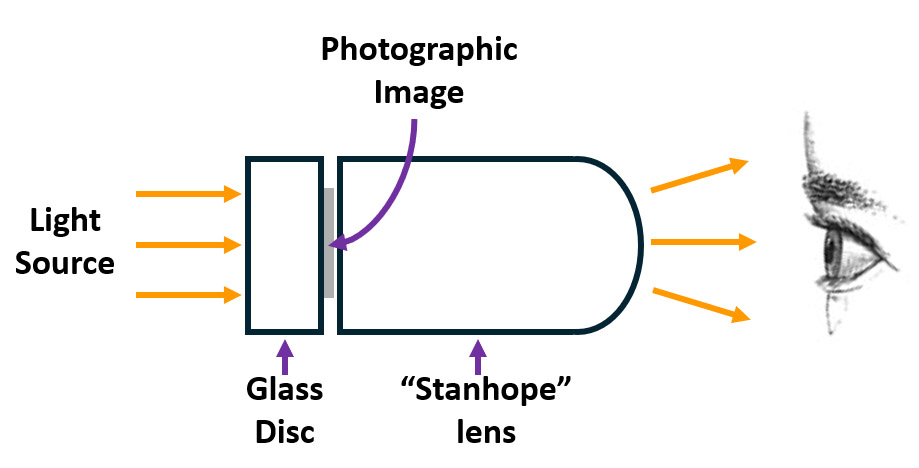

Figure 2.

Schematic of a Dagron “Stanhope” microphotograph viewer. The photograph was produced on a piece of thin glass. This was then fasted to a “Stanhope” lens with Canada balsam, such that the photograph was at the focal point of the lens. The glass with the photograph was then ground into a round disc shape, then inserted into a round hole in a piece of jewelry or other item.

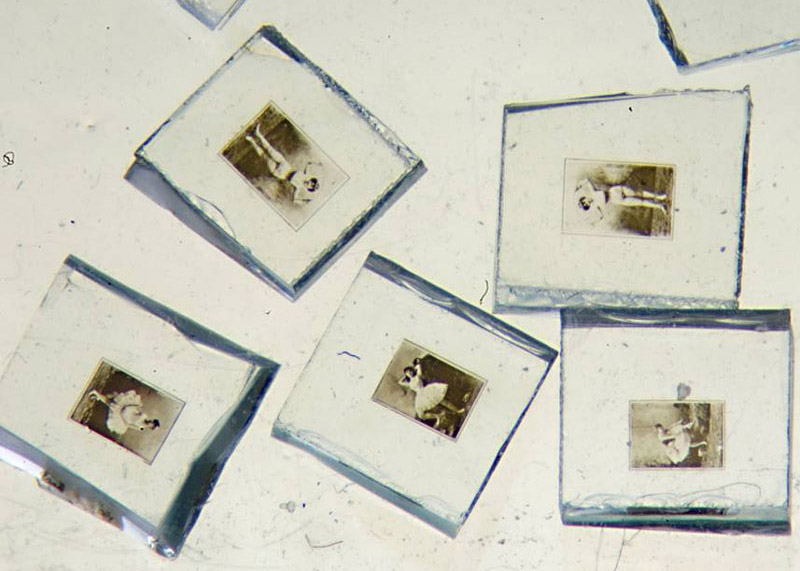

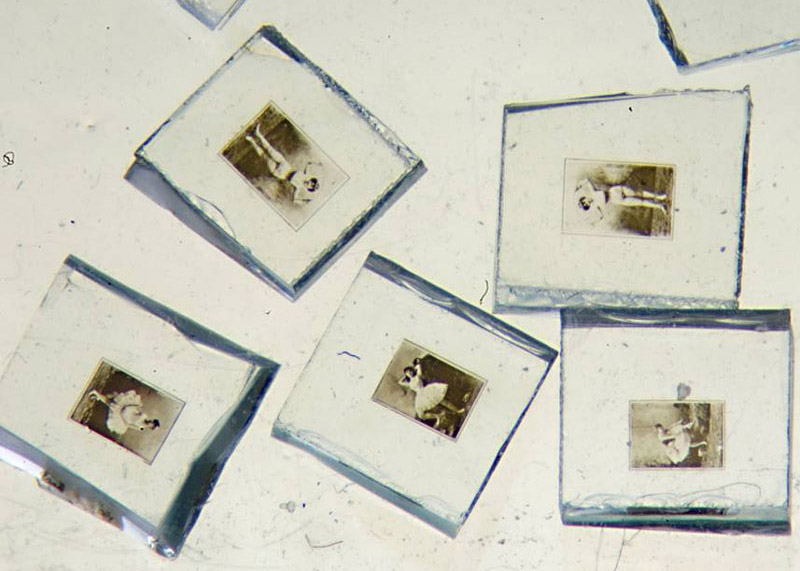

Figure 3.

Microphotographs on glass slips, waiting to be affixed to Stanhope lenses and ground into discs. The maker of these microphotographs is not known. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://americanhistory.si.edu/explore/stories/what-earth-stanhope

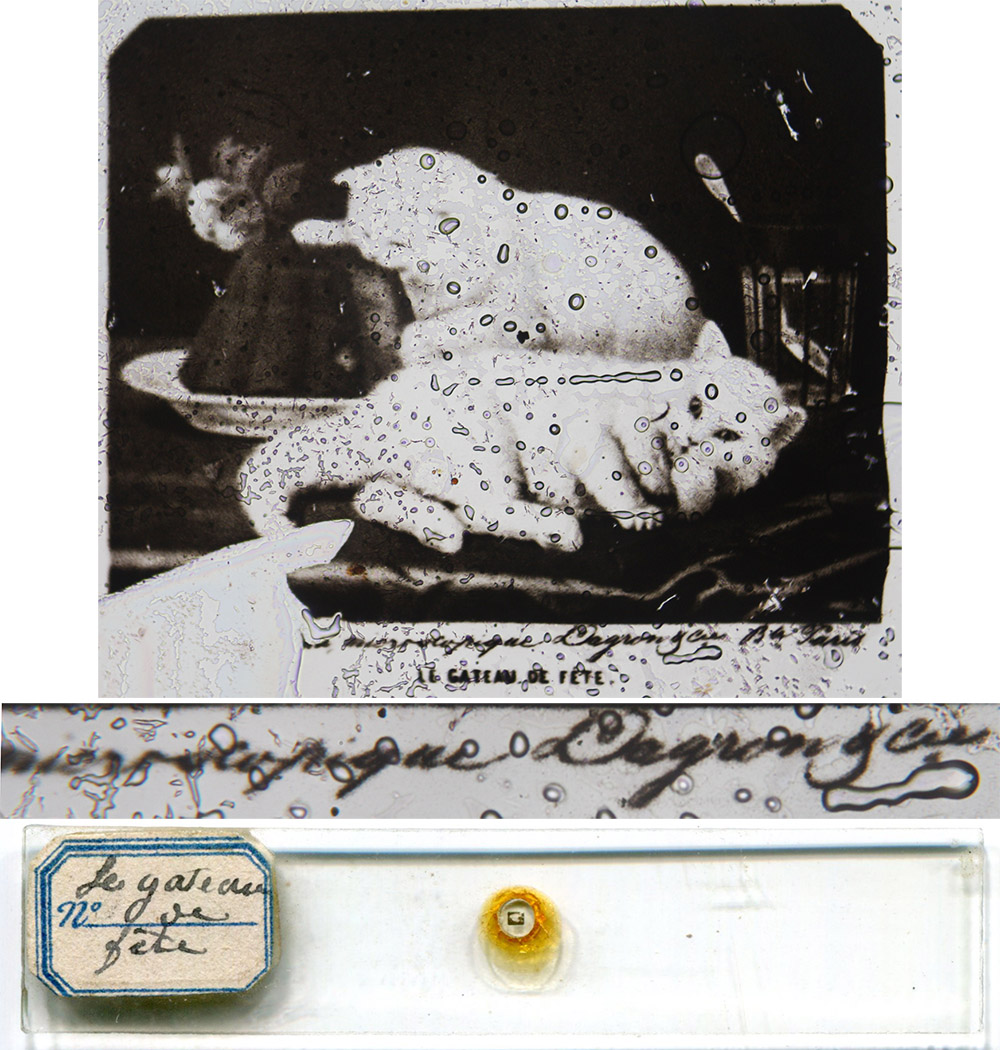

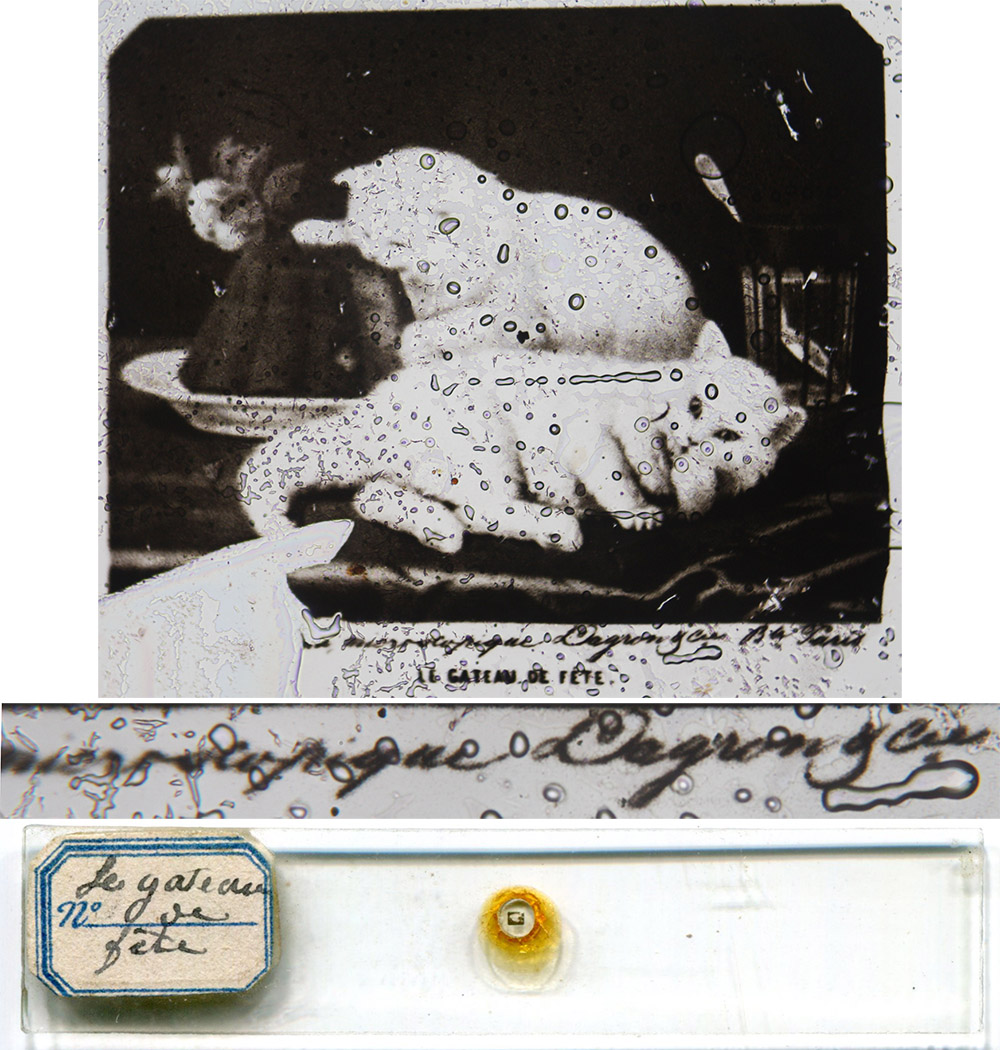

Figure 4.

A microphotograph that is signed by Dagron. It is on a disc of thick glass, evidently removed from a “Stanhope” and mounted onto a glass slide.

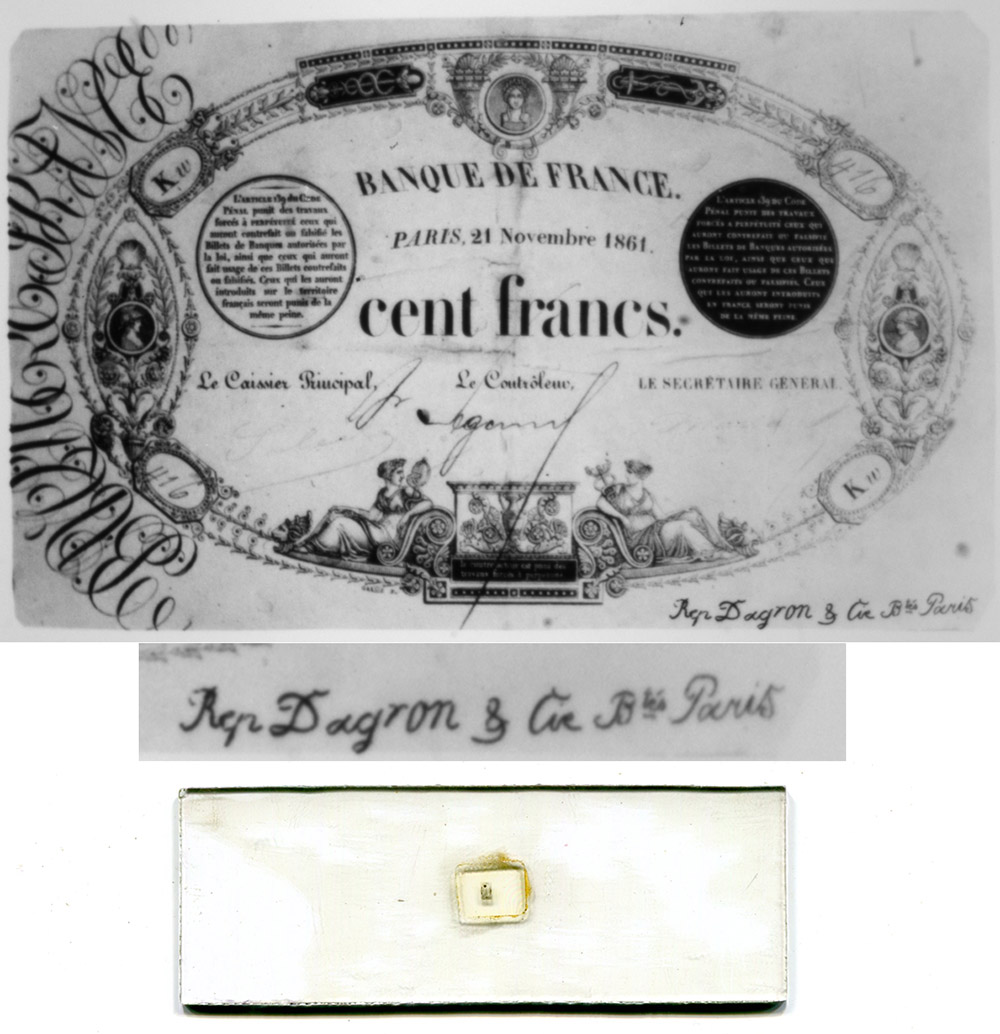

Figure 5.

Another microphotograph that is signed by Dagron, but has a very thin cover slip. This suggests that Dagron also produced microphotograph slides for use with microscopes, in the style of Dancer, Stovin, and others.

Figure 6.

A hand-held viewer that holds 30 "Stanhope" microphotographs on a revolving disc, attributed to Dagron. Adapted by permission from histoiredumicroscope.com. This is one of only two known examples, the other is at https://foticoscollection.com/fr/item/magic-mirror-pare-stanhope/9728

Figure 7.

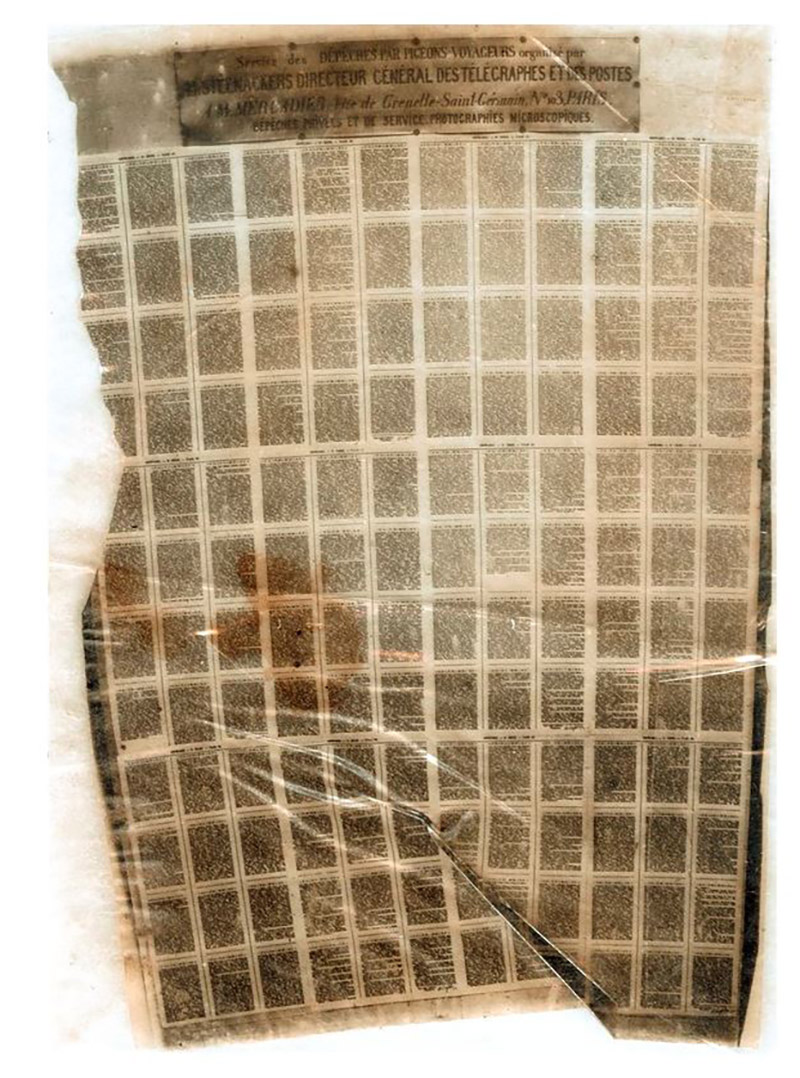

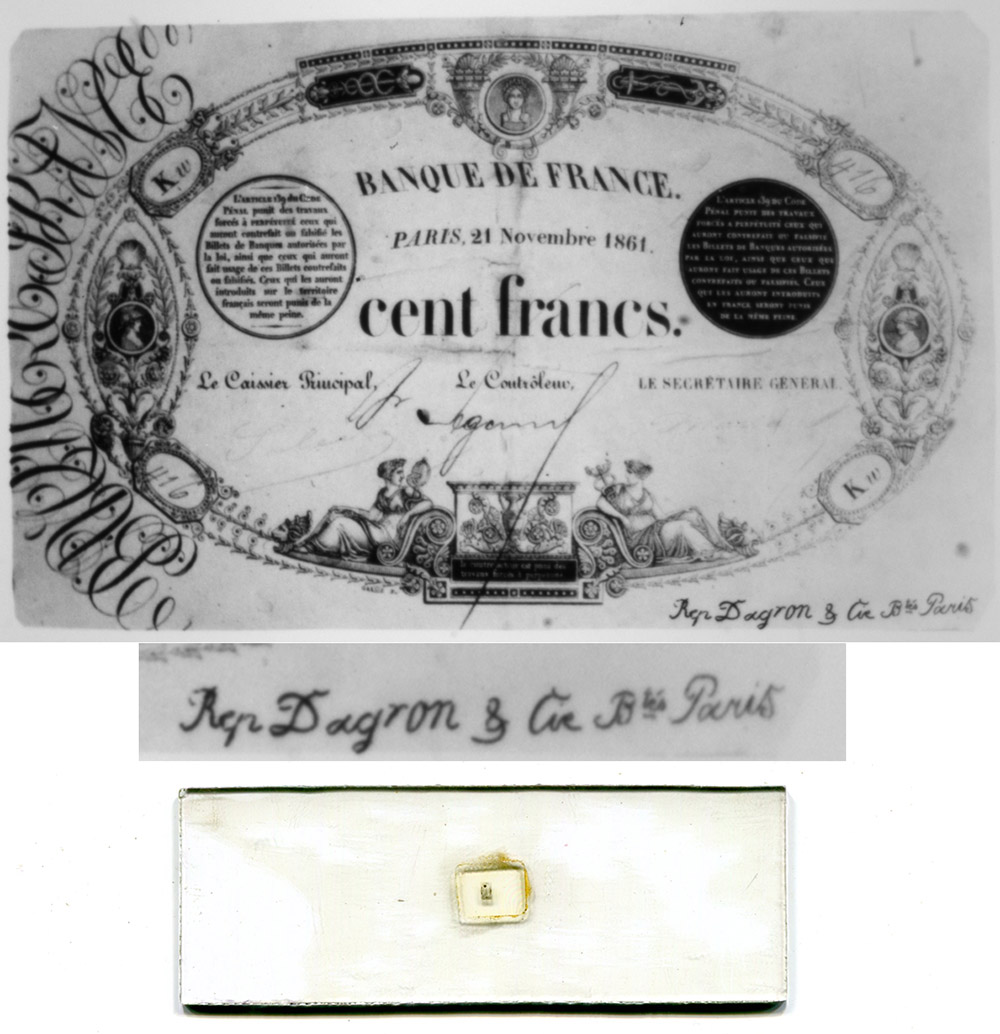

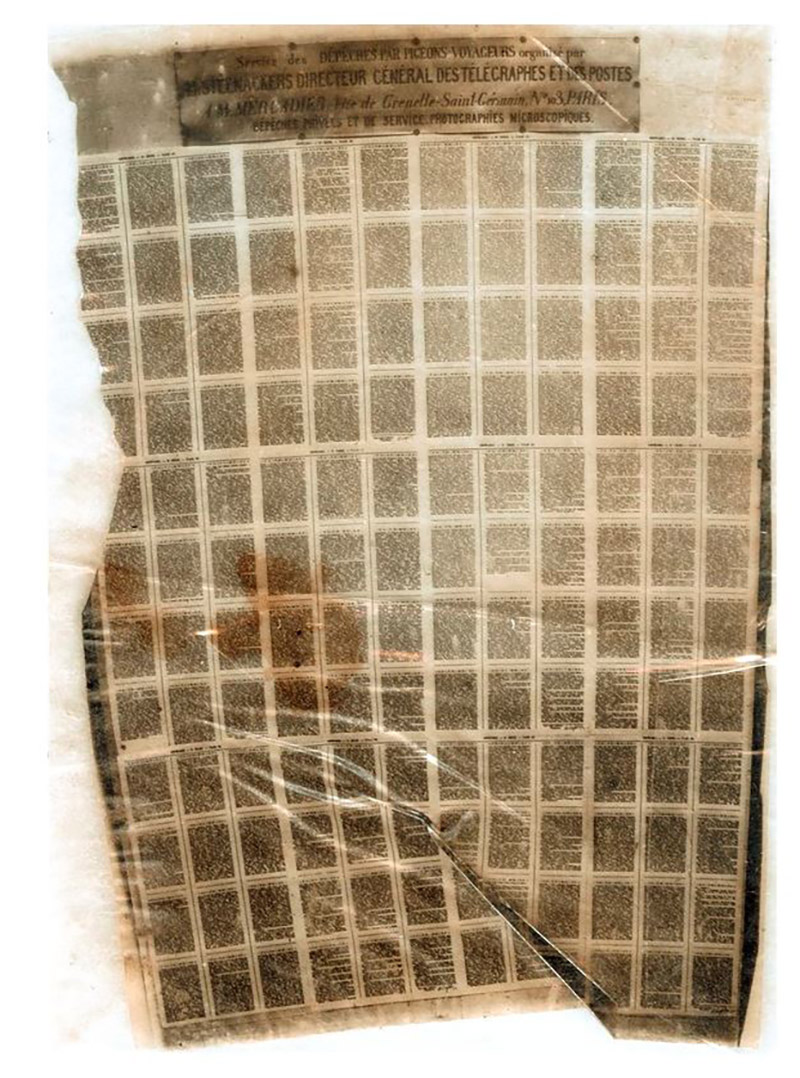

During the 1870-71 Siege of Paris, Dagron operated a “pigeon post”, producing microphotographs/microfilms of newspapers, personal messages, etc. that were flown in to Paris from outside on carrier pigeons. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://www.luminous-lint.com/phoenix.php/images/single/09669009101037182159346604/std/

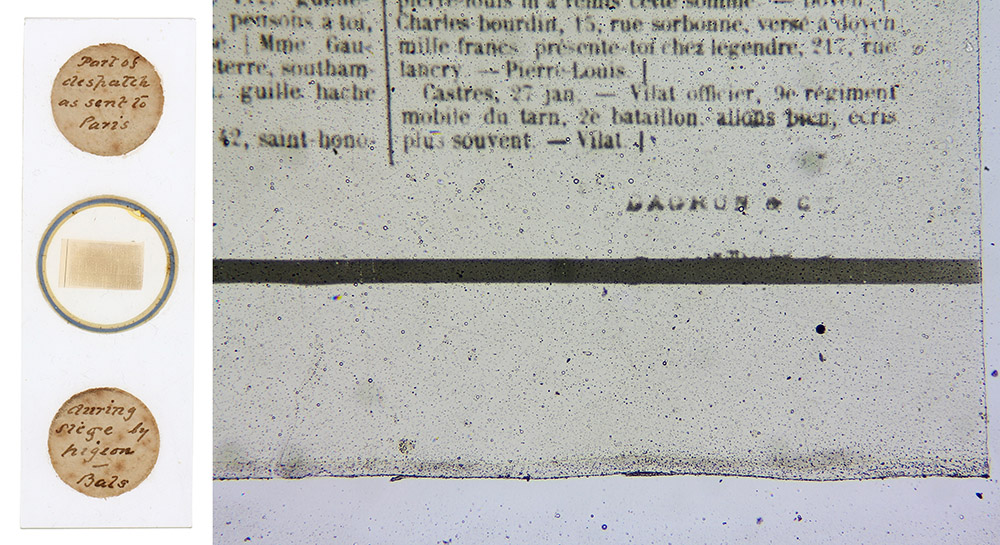

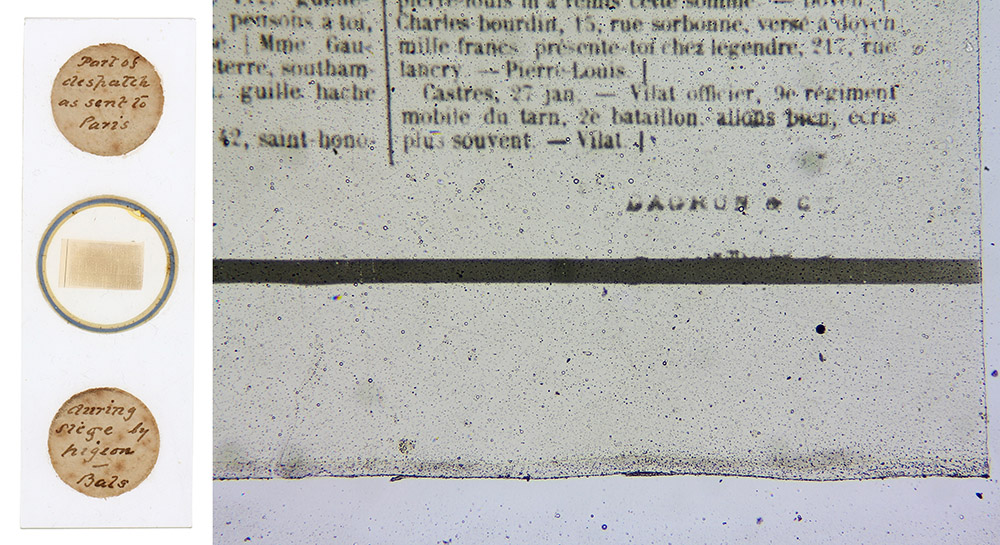

Figure 8.

After the end of the Franco-Prussian War, pieces of Pigeon Post microfilm were sold as souvenirs, often mounted on microscope slides such as this piece that bears Dagron’s name. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Figure 9.

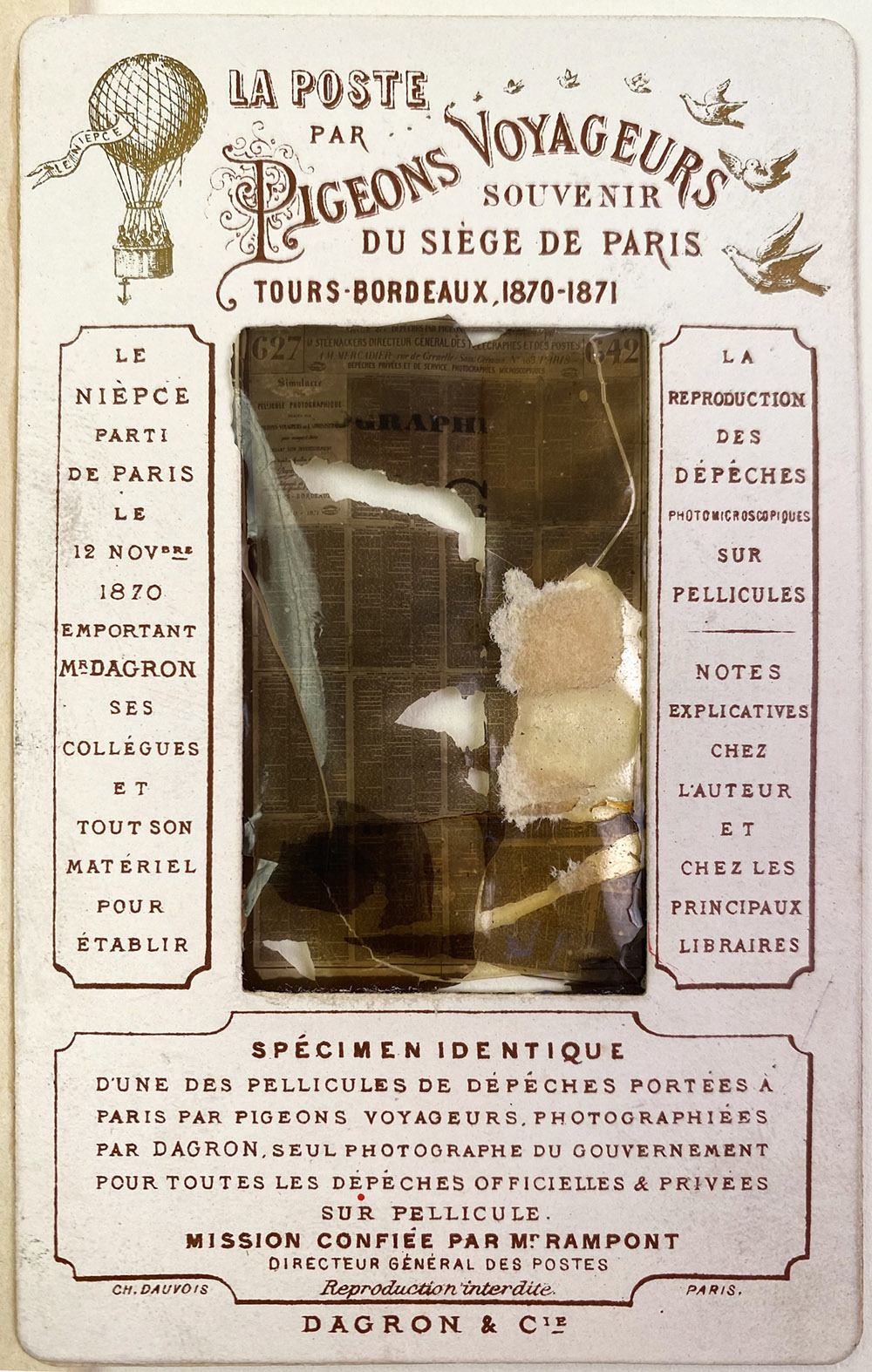

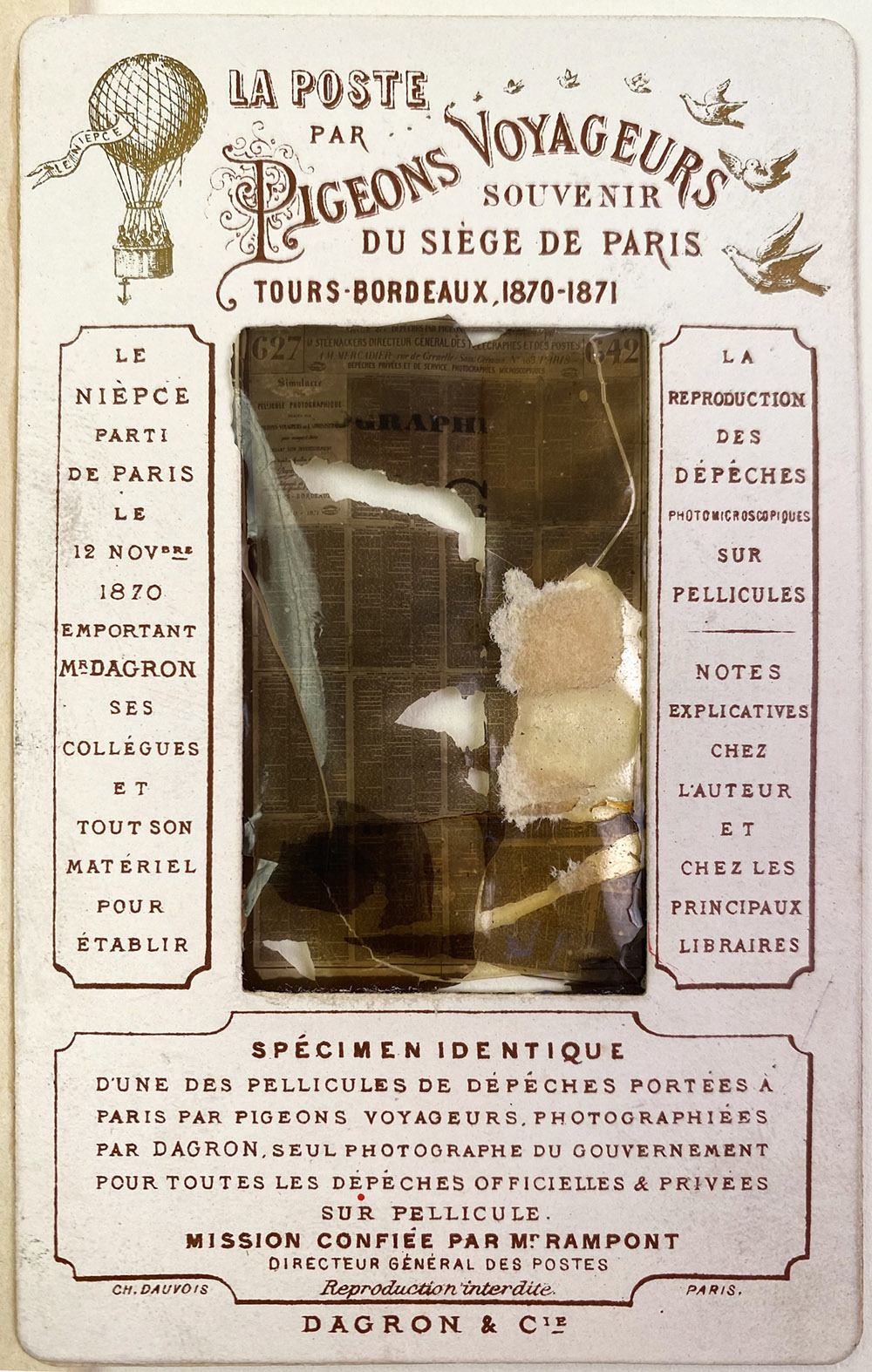

A souvenir card by Dagron, with a piece of Pigeon Post microfilm. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://www.historyofinformation.com/image.php?id=7929

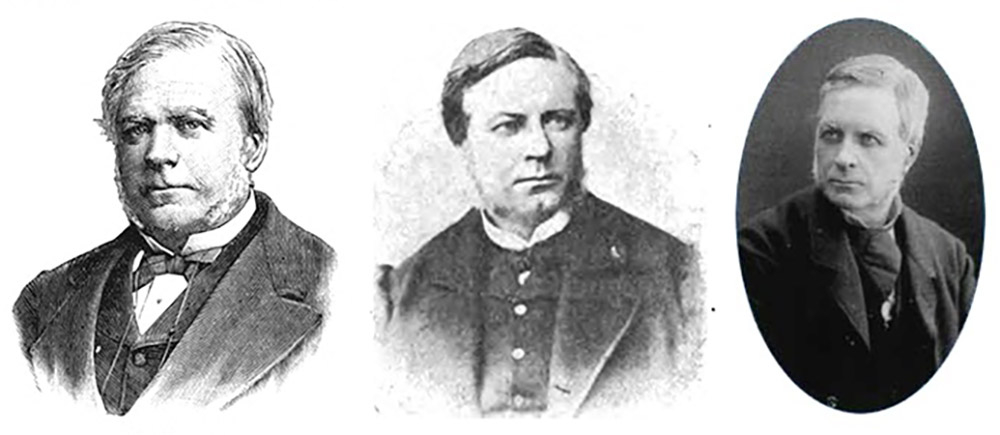

Figure 10.

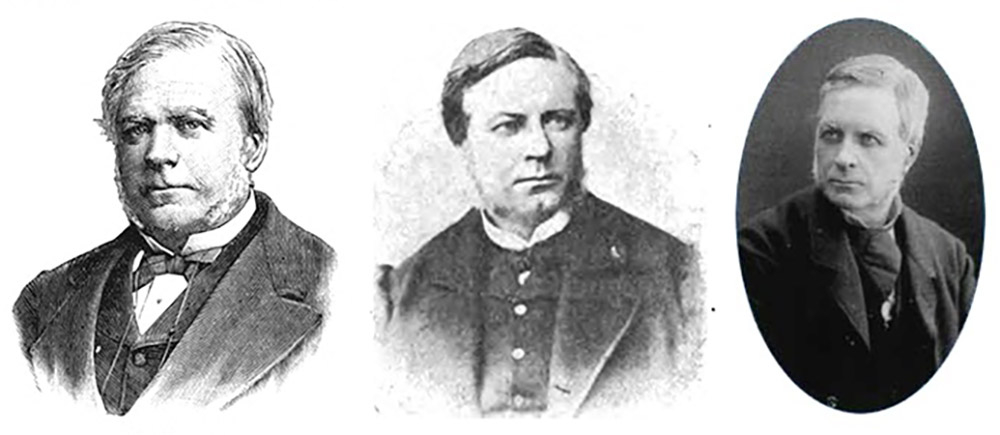

Engravings of Prudent René Patrice Dagron. Left and center, from 1900 obituaries. Right, from en.wikipedia.org/wiki/René_Dagron

Prudent René Patrice Dagron was born on March 17, 1819, in Beaumont, in the department of Sarthe, France. He was a son of René Louis and Catherine Louise Lacroix Dagron. Contemporary French writers referred to Dagron as “Prudent”, while modern authors tend to use his name “René”.

As a teenager, Dagron moved to Paris to educate himself, with particular interest in physics and chemistry. He was in Paris during 1839 when the photographic inventions of Niepce and Daguerre were announced to the public. As a chemist, Dagron became fascinated by photographic processes. He contributed to the development of flexible collodion film as a substrate to replace the polished metal of the daguerreotype.

On October 1, 1846, Dagron married Carolyn Lindy. The couple had 6 children: 4 girls and 2 boys. Dagron’s marriage implies that he had a stable job at the time, but I have not found information on its nature.

During the mid-1850s, Dagron became aware of John B. Dancer’s novelty microphotographs. Dancer had perfected methods by 1853 that produced fine-grained, miniature photographs on glass, which could only be seen in detail with a microscope. Dagron hit upon the idea of placing a microphotograph at the focal point of a simple, “Stanhope” lens, which allows a magnified view without need of a separate microscope. Moreover, these small “Stanhope” microphotographs could be inserted into charms, rings, and other trinkets, which are easy to carry and show off.

Dagron received patents to protect his invention, and brought on investors to provide capital. The Dagron et Cie, business was located at 11 Rue Nueve des Bons Enfants, moving to 66 Rue Nueve des Petits Champs by mid-1861. By 1863, Dagron and Company was reported to be producing 12000 “Stanhopes” a day, employing “hundreds” of workers.

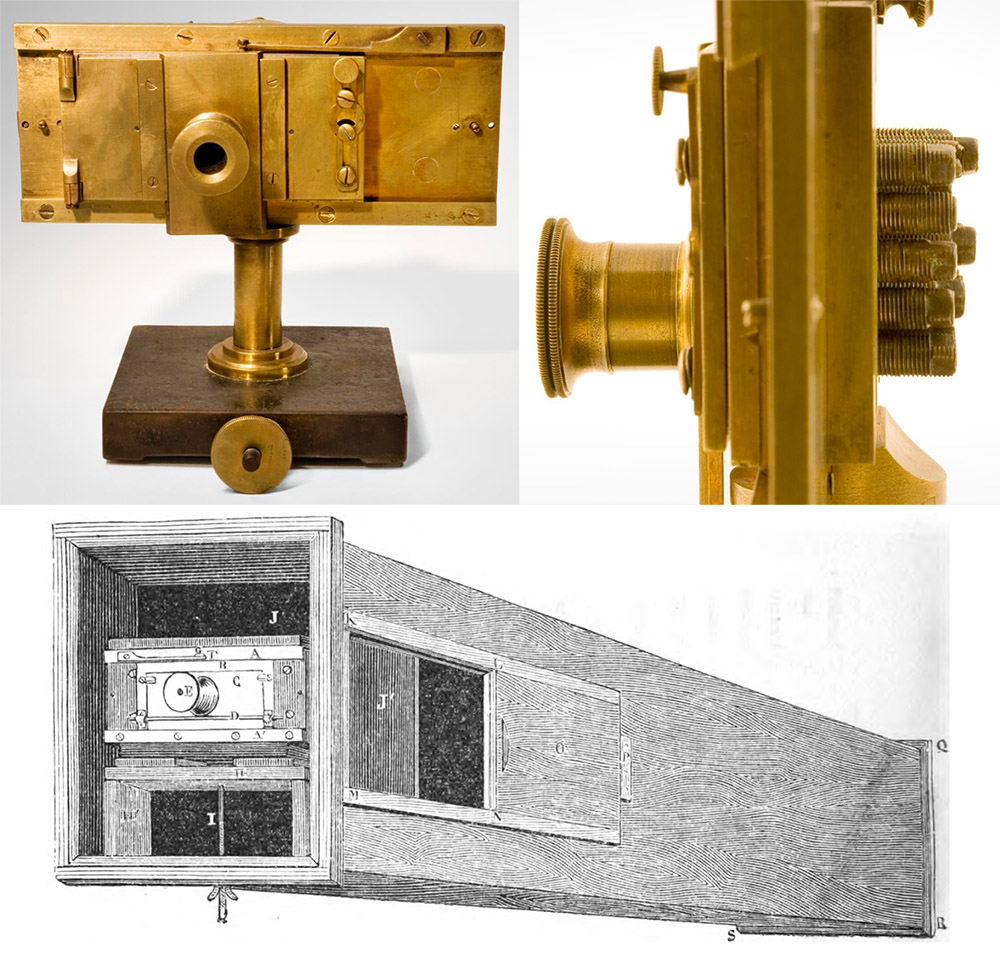

Mass production of the photographic images was achieved through use of a camera that had a sliding lens, such that multiple exposures were produced in quick order (Figure 11). The original image was photographed, to produce a negative of about 3 inches / 7 cm in size. That template was used to produce the microscopical images on glass, which would be in the positive orientation. The glass sheet was then cut apart, each image affixed to a cylindrical “Stanhope” lense, then ground into discs.

Dagron exhibited “Stanhope” microphotographs at the 1862 London International Exhibition, and was awarded an Honourable Mention. The Photographic News wrote, “The application of photography to the production of the enlarged Images of the microscope receives many valuable illustrations … In addition to these some interesting specimens are shown in which the Inverse result is produced. These consist of reduced copies of pictures for microscopic examination; the results, although partaking of the character of toys, may yet become of Important application. Mr. Reeves (United Kingdom, 3144), Mr. Stovin(United Kingdom, 3163), and M. Dagron, France, 1546), exhibit interesting specimens in this class."

Dagron published details on production of his “Stanhope” microphotographs in 1864, Traite de Photographie Microscopique (Figure 12).

His exhibition at the 1865 International Exhibition of Arts and Manufactures in Dublin was described as, “Mr. Dagron also has exhibited some beautiful specimens of microphotography; they are mounted at one end of a small cylinder of glass, the other end of which is ground like a microscopic lens, generally called the Stanhope lens, but of which Sir David Brewster claims the invention. The tube is about one-quarter of an inch long, its diameter one-sixteenth of an inch. It is wonderful to think that this constitutes a microscope, with its lens at one end and the photograph at the other. Although this photograph is imperceptible to the naked eye, still, by looking at it through the minute microscope, we see the portrait of a person as large as nature; a page of the Bible we can read as easily as in the book. This minute optical instrument, with its imperceptible photograph, can be mounted in rings, watch-keys, pin, or any other small ornaments. The productions of M. Dagron are a very charming and wonderful combination of photography and microscopy, in which he has seen his way to a considerable branch of manufacture; and for this object he has formed a large establishment in which, by a well-organized division of labour, by well-combined machinery, everything is done on the spot - taking the large photograph, reducing to the microscopic size, manufacturing the small microscope, mounting the picture, making the articles of jewelry themselves. M. Dagron has exhibited the instrument by which he can reduce any photograph to the microscopic size, and by which he can produce at once, upon a collodion plate of about three inches by three inches, twenty-live or thirty microscopic pictures. The pictures are afterwards divided by a cutting diamond, ground in disks, and fixed at the end of the small microscope. The whole process is very rapid, simple, and ingenious, and so well constructed, that the microscope, with its photograph, can be sold as low as twelve shillings per dozen, ready to be mounted by the jeweller in any kind of trinket or ornament.

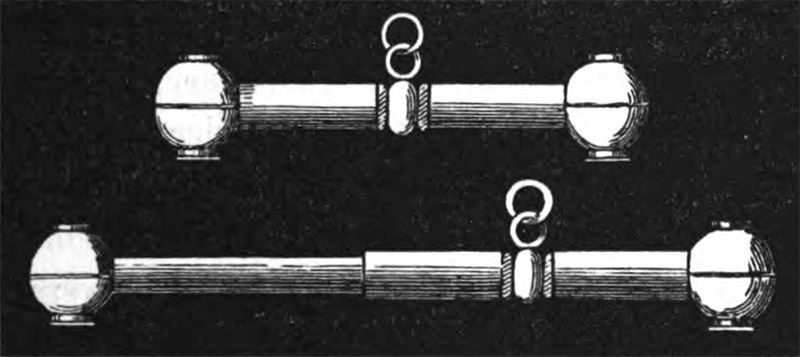

At the suggestion of Sir David Brewster, M. Dagon has produced stereoscopic pictures, and mounted them at the two ends of the gold bar by Which a chain is held in the button-hole of the waistcoat. The gold bar is no longer than two inches, and it mav be extended by a sliding tube to two and a half, to suit any separation of the eyes. The idea of a microscopic stereoscope is very curious.” (Figure 13).

Unfortunately for Dagron, French law of the time did not favor patents and monopolies, and he lost protection for his invention. Other people now openly produced “Stanhopes” according to Dagron’s methods.

In 1867, it was reported that Dagron had begun producing porcelainware on which photographs were applied, “M. Dagron, 66, rue Neuve des Petits-Champs, nous a montré des porcelaines, des faïences, des cristaux ornés de portraits ou de vues photographiques d'un effet délicieux qu'il obtient par un procédé très-simple, très-efficace, très-économique. Il attend pour fabriquer en grand d'avoir obtenu des noirs plus beaux encore” (“Mr. Dagron, 66, rue Neuve des Petits-Champs, showed us porcelain, earthenware, crystals decorated with portraits or photographic views with a delicious effect that he obtains by a very simple process, very efficient, very economical. He waits to produce on a large scale until he has obtained even more beautiful blacks”).

The Franco-Prussian War broke out in July, 1870. By September, the Prussians had laid siege to Paris. A variety of methods were attempted to get information into and out of Paris, with varying levels of success. Balloons could leave Paris, but it was very difficult for them to return and land precisely in the city. Carrier pigeons could carry only a small piece of paper. Dagron proposed making microphotographs on collodion film, which could be carried from outside into Paris on pigeons, then the text projected onto a screen to be read. The government approved the idea, and on the morning of November 12, 1870, two ballons left Paris carrying Dagron, assistants, aeronauts, and several hundred kilograms of photographic equipment. Despite gunfire from the Prussians, a crash landing, and near-capture, Dagron, his colleagues, and most of the equipment managed to get to safety in Bourdeaux. There, they set up an office to produce microfilms, to be sent to Paris via pigeons. The process was described in the English press as,

“The despatches, public and private, were first printed (to save space and render them more legible) on pages of folio size, sixteen of which were placed side by side, forming a large sheet about 54 inches long and 32 inches wide. This was reduced by photography to 1/800 of its original area, the impression being taken on a small pellicle of transparent gelatinous collodion, 2 inches long and 14 inch wide, and weighing about three-quarters of a grain. The figure in the margin is a full-sized representation of one of these pellicles now before us. The sixteen pages of letterpress will be seen in their reduced size; each page consists of about 2000 words, and, therefore, the whole impression contains as much matter as sixty-five pages of this review.

We have read the despatch with a powerful microscope, and find it contains a great number of messages, chiefly of personal interest, to inhabitants of Paris, from many parts of France. … There are also many ‘Dépêches Mandats’, or post-office orders, payable to persons in Paris, from correspondents in the country.

Every pigeon carried twenty of these leaves, which were carefully rolled up and put in a quill; they contained matter enough to fill a good-sized volume, and yet the weight of the whole was only fifteen grains. When the pigeon arrived at his cote in Paris, his precious little burden was taken to the Government-office, where the quill was cut open, and the collodion leaves were carefully extracted. The next process was to magnify and read them by an optical apparatus, on the principle of the magic lantern, or rather of the well-known electric illustrator, which plays such an important part in the scientific lectures at our Royal Institution. The collodion film was fixed between two glass plates, and its image was thrown on a white screen, enlarged to such an extent that the characters might be read by the naked eye. The messages were then copied and sent to their destination.

The despatches were repeated by different pigeons, for although the communication was established many causes interrupted its regularity. The Prussians were powerless against the winged messengers (it is said they attempted to chase them with birds of prey); but there were more real obstacles in fogs, which prevented the pigeons seeing their way, and in the great cold, which was found to interfere with their powers, particularly when the ground was covered with snow. There were sent out of Paris 363 pigeons, but only 57 returned, and some of these were absent a long time.

The charge for private despatches by pigeon was 50 centimes per word; but to facilitate the service, the Parisians were directed to send to their friends in the country, by balloon, questions which could be answered by pigeon with the single words, 'Yes' or 'No.' Forms were prepared, something like our postage-cards, and four such answers were conveyed for one franc.

The Parisians will long recollect the excitement produced by the arrival of their pretty couriers; no sooner was a pigeon seen in the air than the whole city was aroused, and remained in a state of intense anxiety till the news was delivered. An engraving was afterwards published representing Paris, as a woman in mourning, anxiously awaiting, like Noah's imprisoned family, the return of the dove.

The aerial post was undoubtedly a great success. It could not indeed save France, or deliver the Capital; but it was an immense comfort and advantage to the Parisians as establishing, during the whole of the siege, a correspondence with the exterior, which without it would have been impossible. And had the cause been less desperate, it is not improbable that the balloons might have turned the scale, by giving to the French substantial advantages in their means of communication”.

Dagron wrote about his exploits with the Pigeon Post in a booklet, La Poste par Pigeons Voyageurs (Figure 14).

When the war ended in January, 1871, Dagron resumed his photographic business in Paris. He sold souvenirs of the Pigeon Post, along with his “Stanhope” trinkets and professional photographs (Figures 15-17).

As noted above, Dagron lost his patents for “Stanhope” microphotographs during the 1860s, and so did not reap the financial benefits that he could have obtained with a monopoly on his invention. His advances in microfilm technology developed for the Pigeon Post also failed to provide much money.

Seeking other avenues for support, Dagron invented new writing inks, and developed “carbon” paper that could produce up to 12 clear copies. An obituary of Dagron wrote, “He found an intelligent and honest capitalist, who agreed to take charge of the exploitation of this invention on condition of providing him with a life annuity, which sufficed for all his needs” (paraphrased from French).

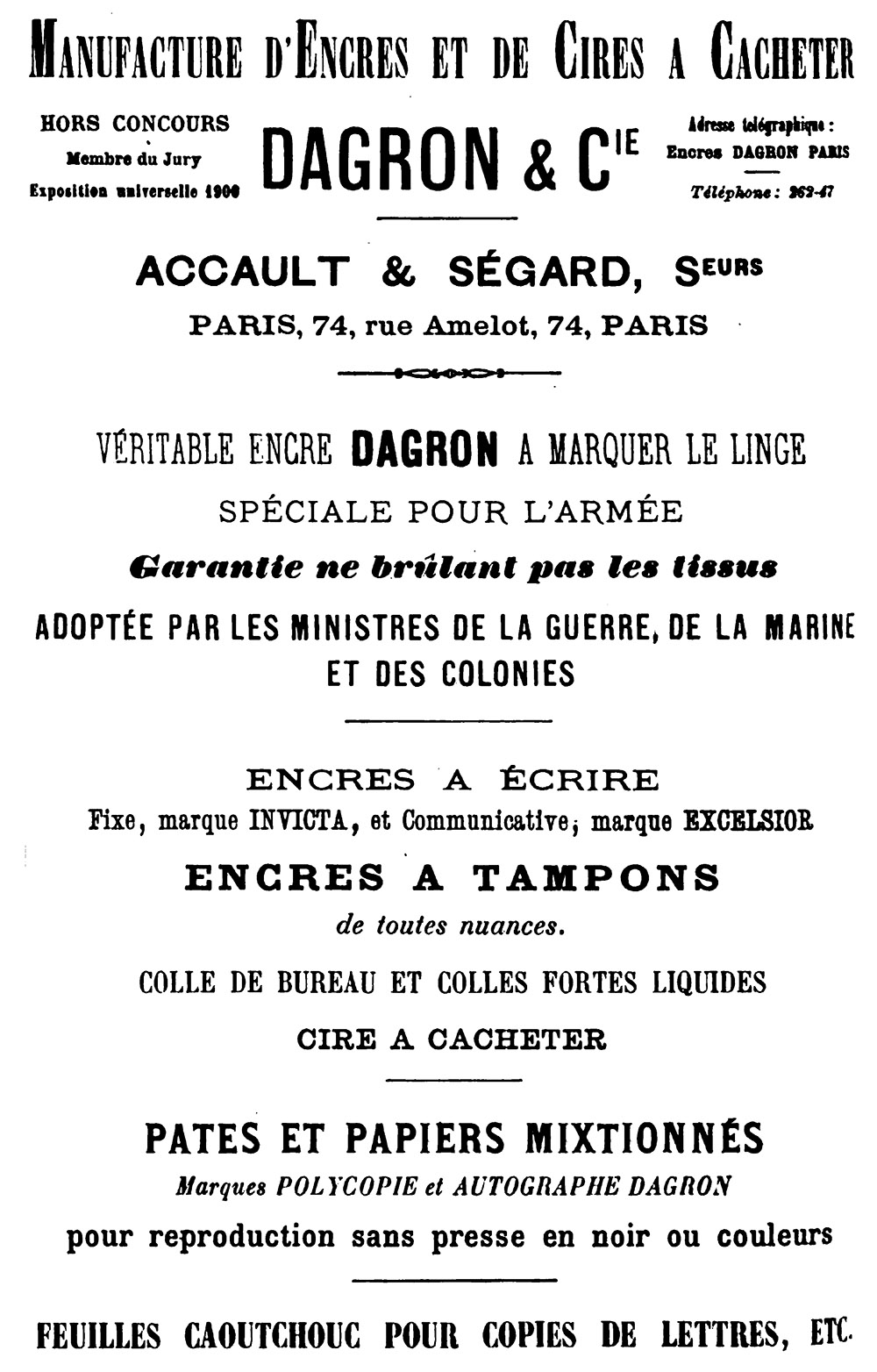

“Autographie Dagron” was first advertised in the 1882 Annuaire et Almanach du Commerce, de l'Industrie, de la Magistrature et de l'Administration, as being manufactured by Maison Charles Blancan, of 154 Rue St. Denis. By the next year, “Dagron et Cie.” was making the ink and papers itself, at 80 Rue St. Denis. A retail shop at 74 Rue Amelot was opened by 1888.

Dagron’s inks and associated products won numerous awards. They won a Silver Medal at the 1889 International Exposition, with the jury’s report (translated):

“MM. Dagron et Cie, ink manufacturers, rue Amelot, 74, in Paris. This house, founded in 1882, has a turnover of around 300,000 francs and employs 35 to 40 people. Its manufacture includes writing inks of all kinds, stamp inks of all colors, sealing waxes, liquid erasers, cold glue, etc. Among the items on display, we will highlight: mixed paper, used for the reproduction, without press or special tools, of writing, drawing, etc. This paper, an innovation of the house, is manufactured mechanically in rolls, which makes it possible to obtain the reproduction of plans or drawings of a very large surface, a result that pulps in bowls, due to their necessarily restricted dimensions, cannot give. Indelible ink for marking linen, adopted by the Ministry of War and the Ministry of the Navy for marking military effects. Excelsior communicative ink, which, while combining the qualities of the best known types, offers the advantage of not bleeding through the paper, even if it is imperfectly bonded. To prove this last quality of their ink, MM. Dagron and Company had presented to the jury copies obtained from a letter written on August 8, 1888, a result which clearly demonstrated that the substance had remained on the surface of the paper, but had not penetrated. The Dagron house had already obtained the following awards: silver medal, Exhibition of Decorative Arts, Paris, 1882; bronze medal, Amsterdam, 1883; gold medal, Industrial Arts, Paris, 1886; bronze medal, Hanoi, 1887”.

Wife Carolyn died in 1897. Trade directories indicate that Dagron ended his photographic business during that year. Prudent René Dagron died on June 13, 1900.

Dagron and Company was continued under the proprietorship of Misters Accault and Ségard. By 1907, Ségard was the sole owner.

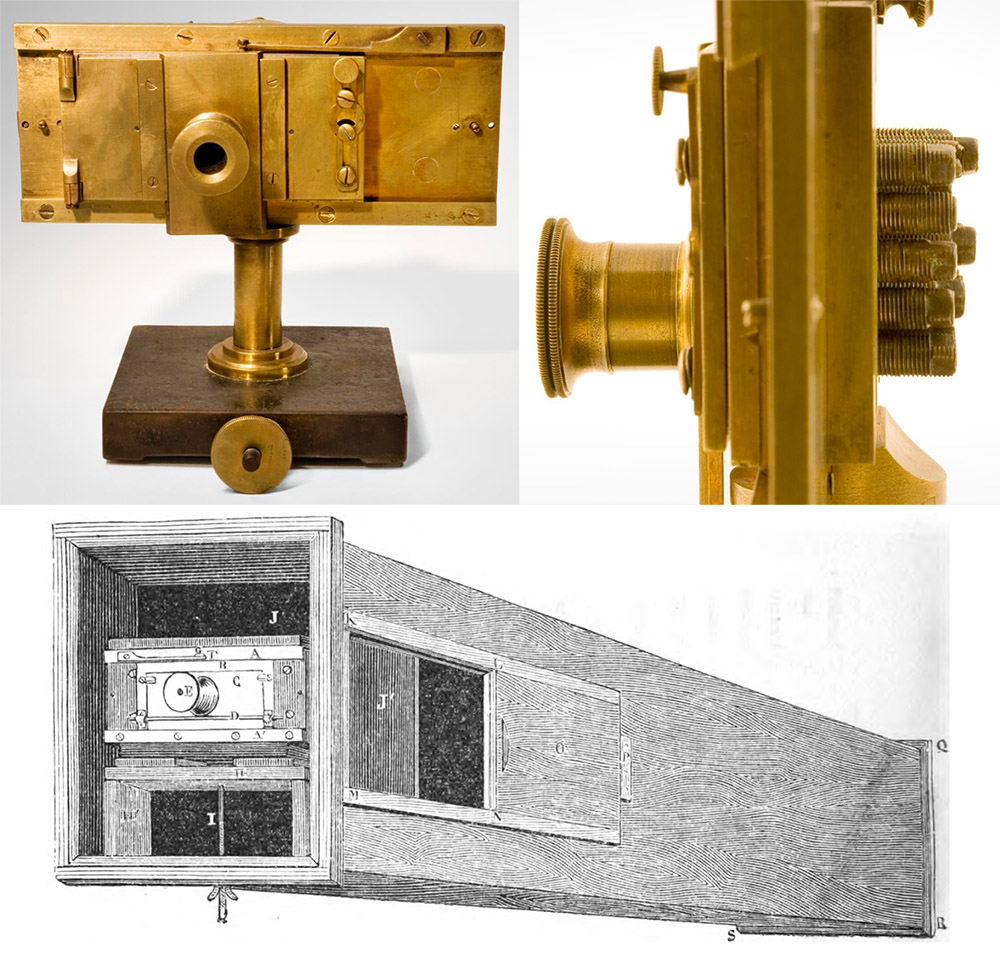

Figure 11.

Top, a Dagron camera that was used to produce multiple microphotographs. Bottom, diagram of a Dagron camera in a wooden cabinet. Dapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co8208602/dagron-microphotographic-camera and from Moigmo, 1864.

Figure 12.

Title page from Dagron’s 1864 booklet “Traite de Photographie Microscopique”.

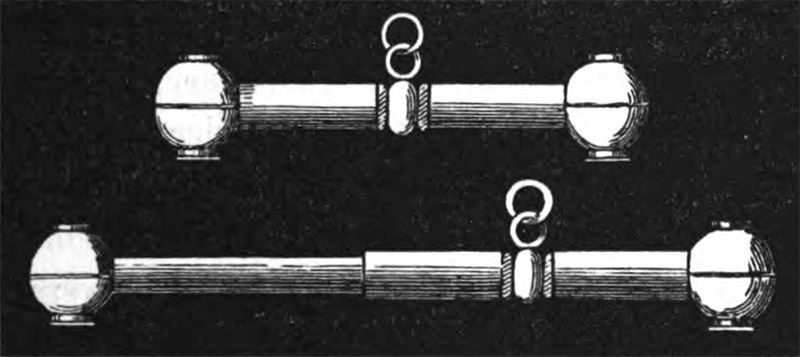

Figure 13.

Diagrams of Dagron’s stereoscopic “Stanhope” microphotographs. Paired imaged were viewed with each eye, giving a three-dimensional appearance. From Moigmo, 1864.

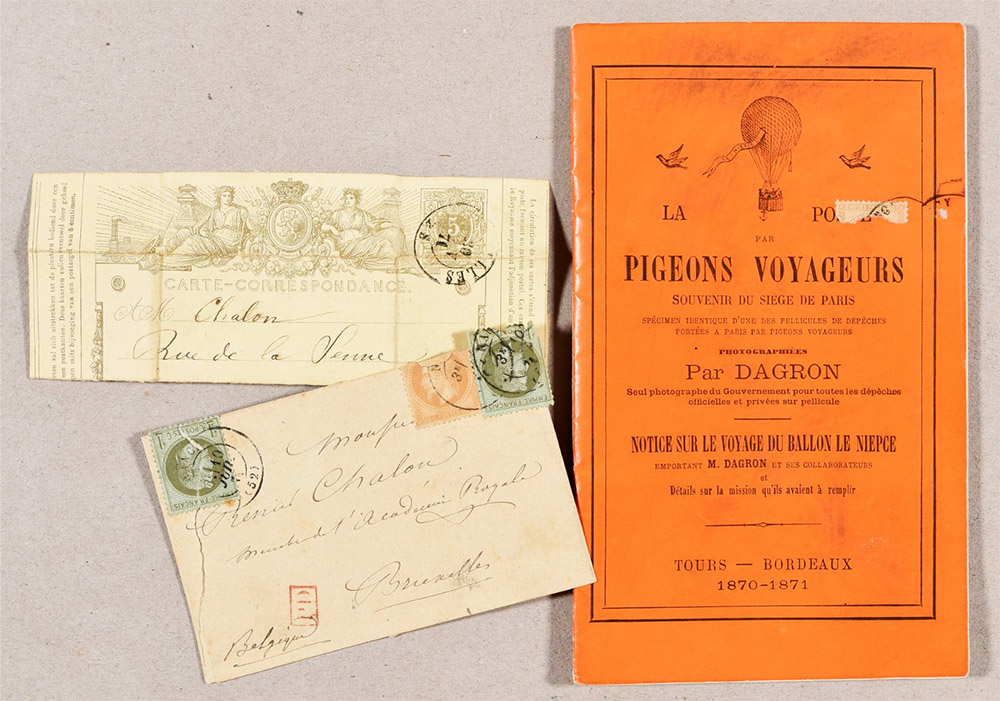

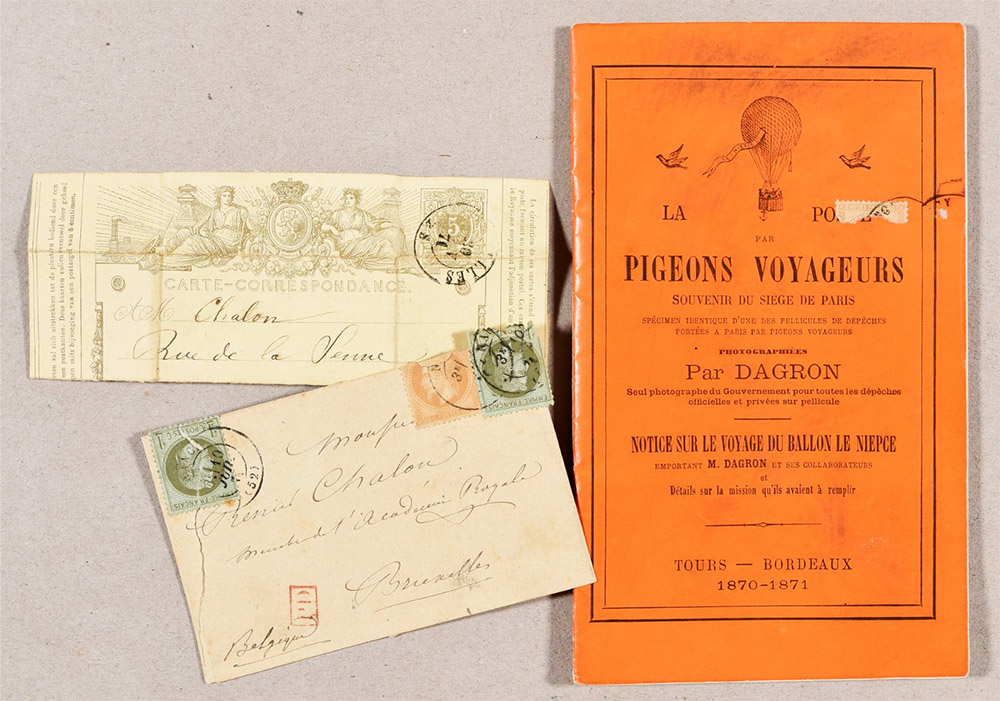

Figure 14.

Dagron’s “La Poste par Pigeons Voyageurs”, published ca. 1871. Image adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

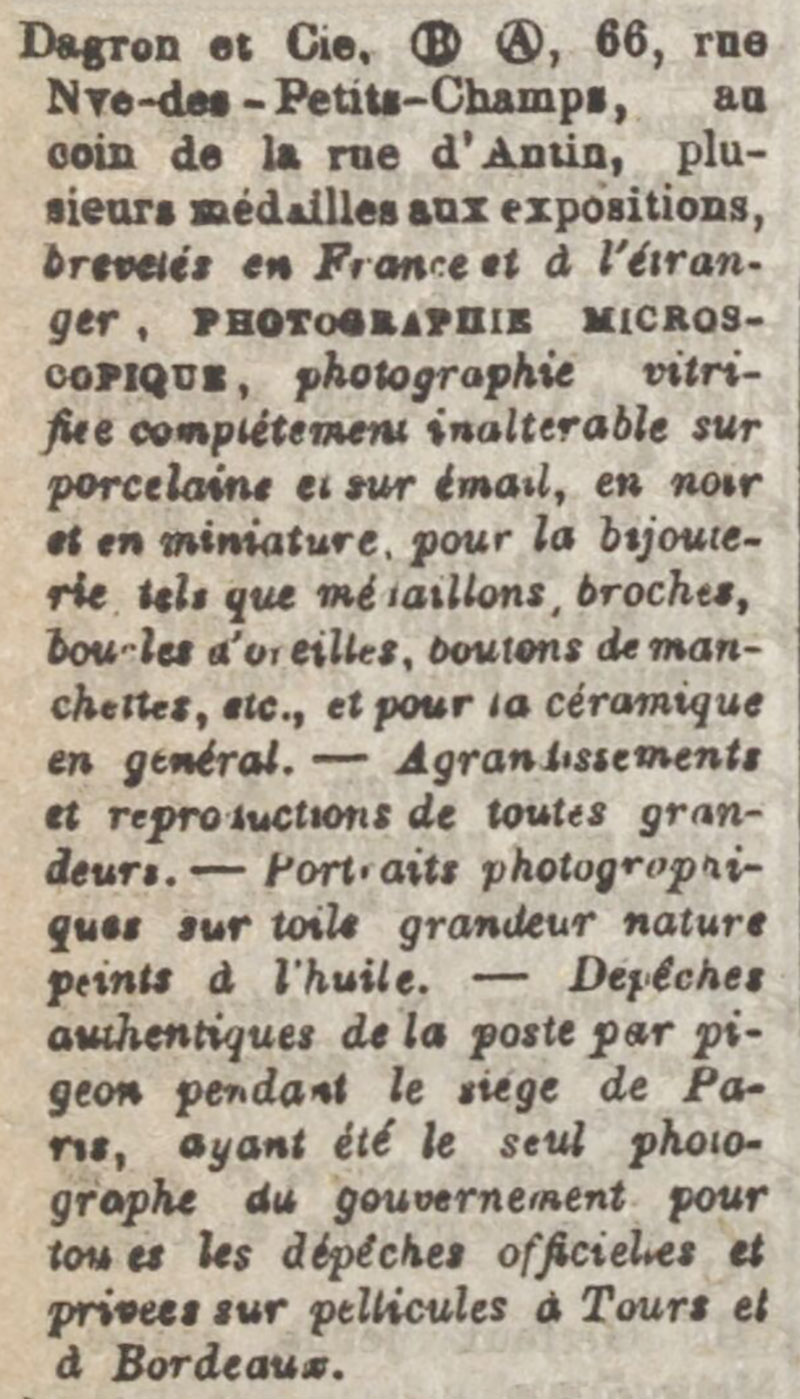

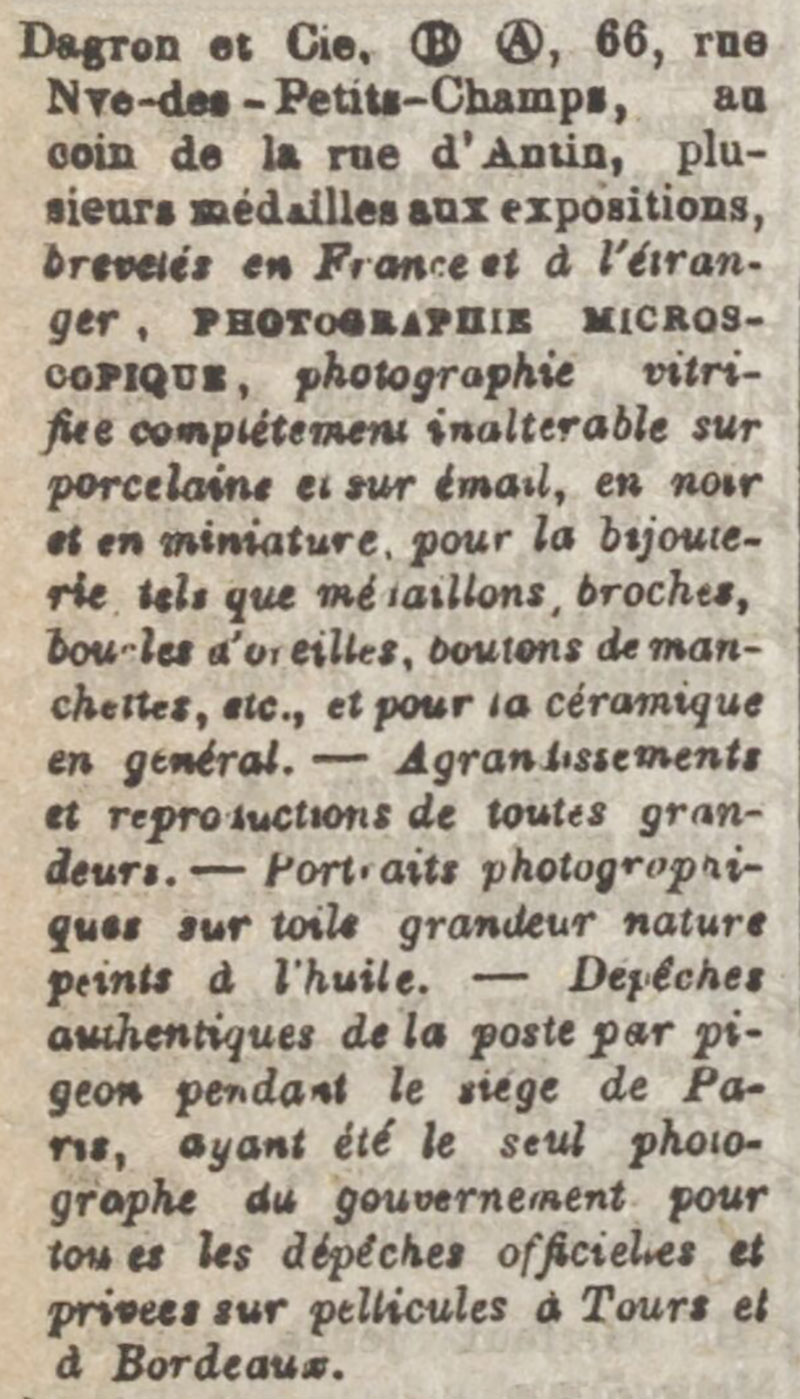

Figure 15.

Dagron’s entry in the 1872 “Annuaire et Almanach du Commerce, de l'Industrie, de la Magistrature et de l'Administration’, describing that he provided “Stanhope” microphotographs, professional photographs, and souvenirs of the 1870-71 Pigeon Post.

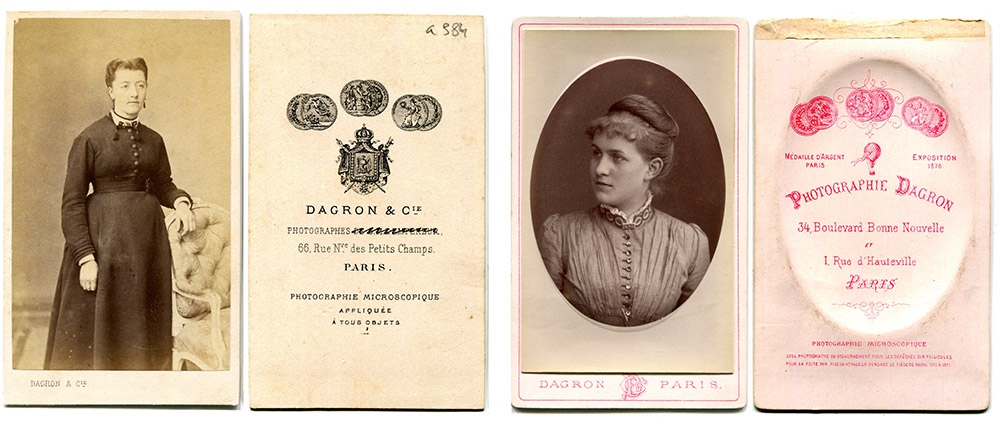

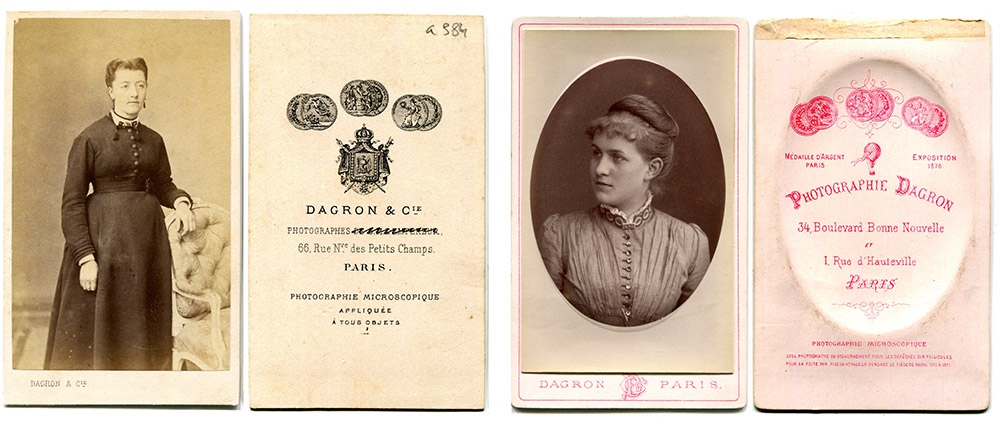

Figure 16.

Carte-de-visite photographs by Dagron. His business was located at 66 Rue de Nueve des Petits Champs from 1861 through 1875, and 34 Boulevard Bonne Nouvelle from 1875 until 1897.

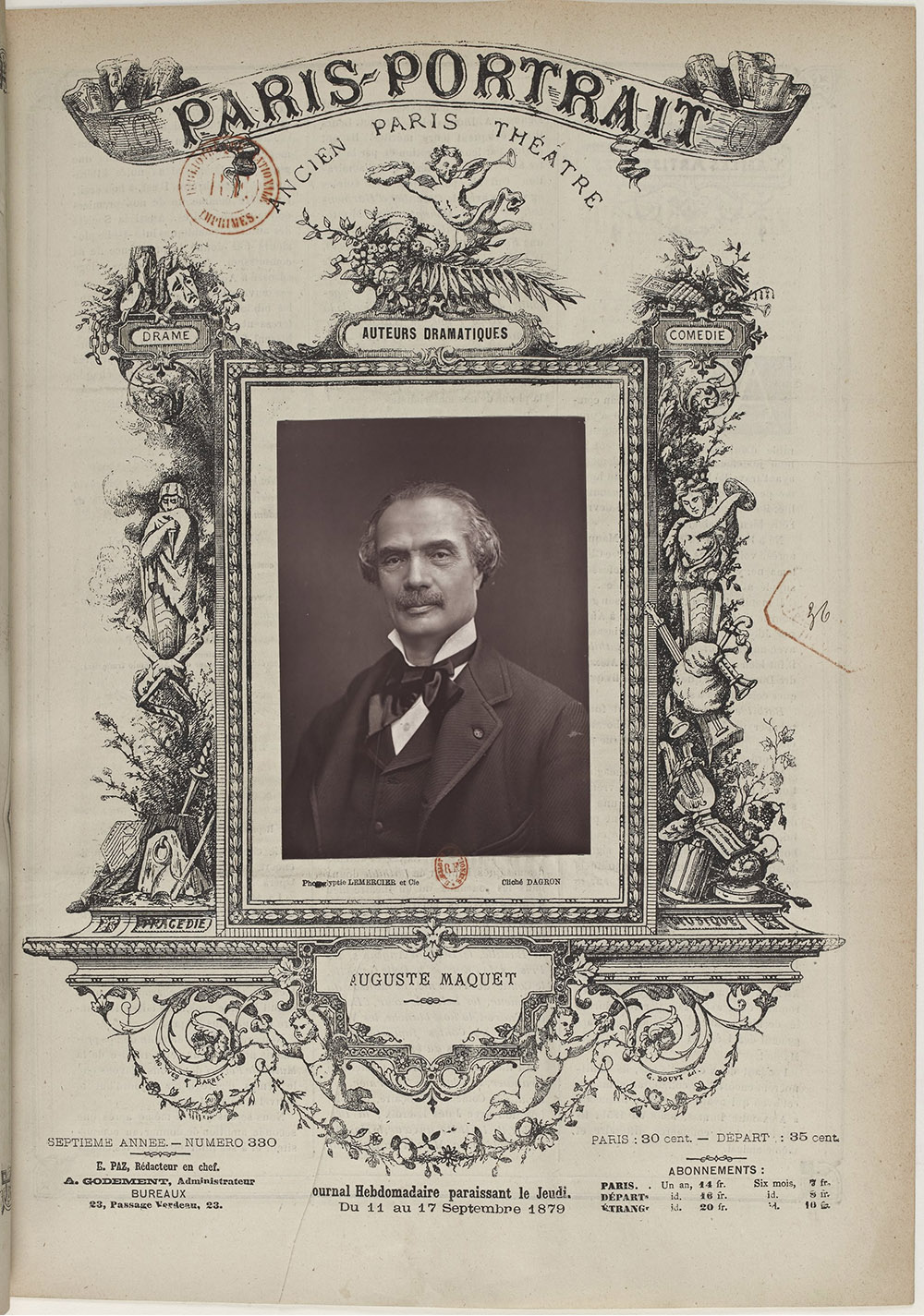

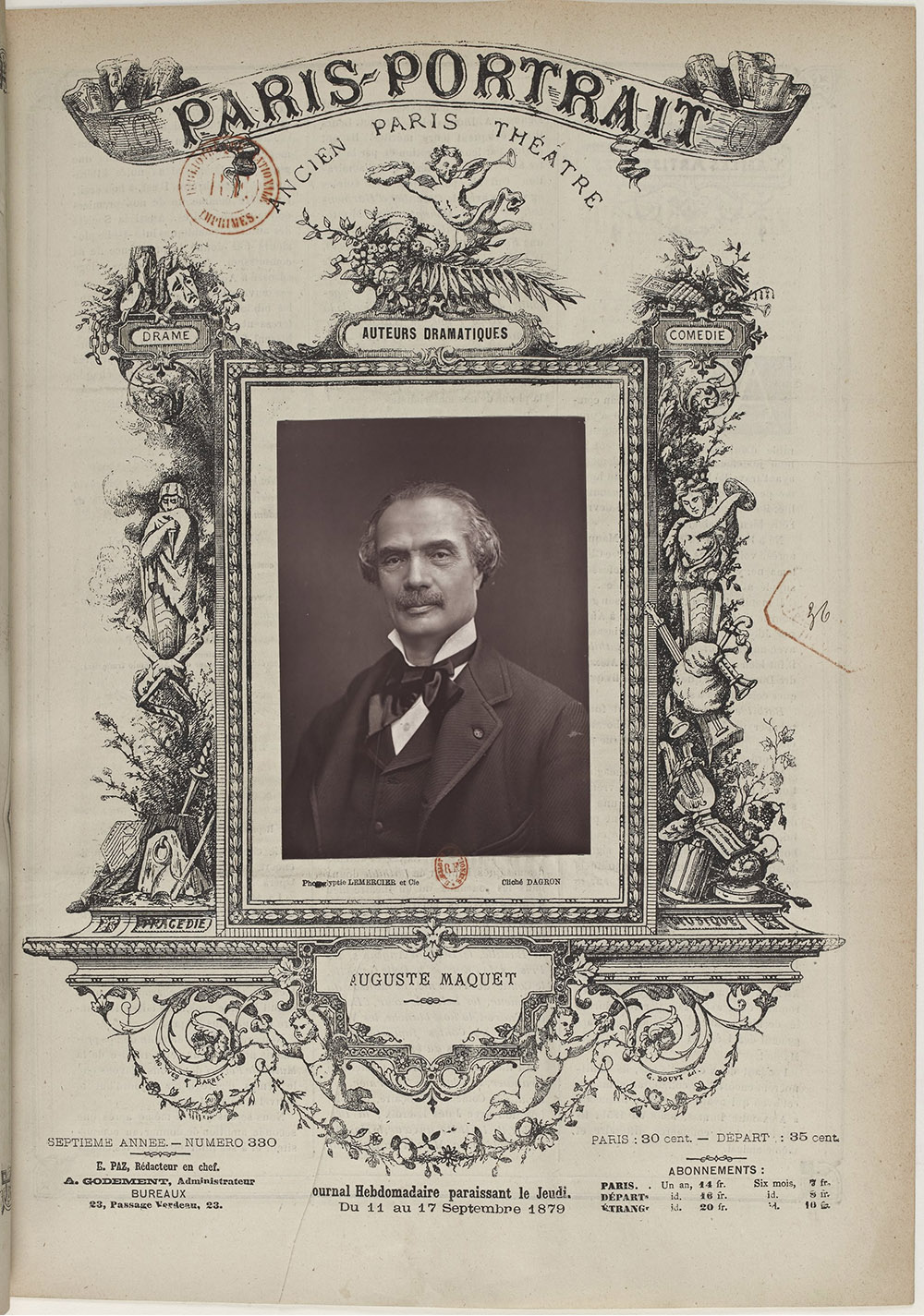

Figure 17.

The low cost of producing photographs in the latter decades of the 19th century led to a fad of collecting photographs of celebrities. This collectible card of author Auguste Maquet was produced and sold by Dagron. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://www.luminous-lint.com/phoenix.php/images/single/39366971016632392059753/std/

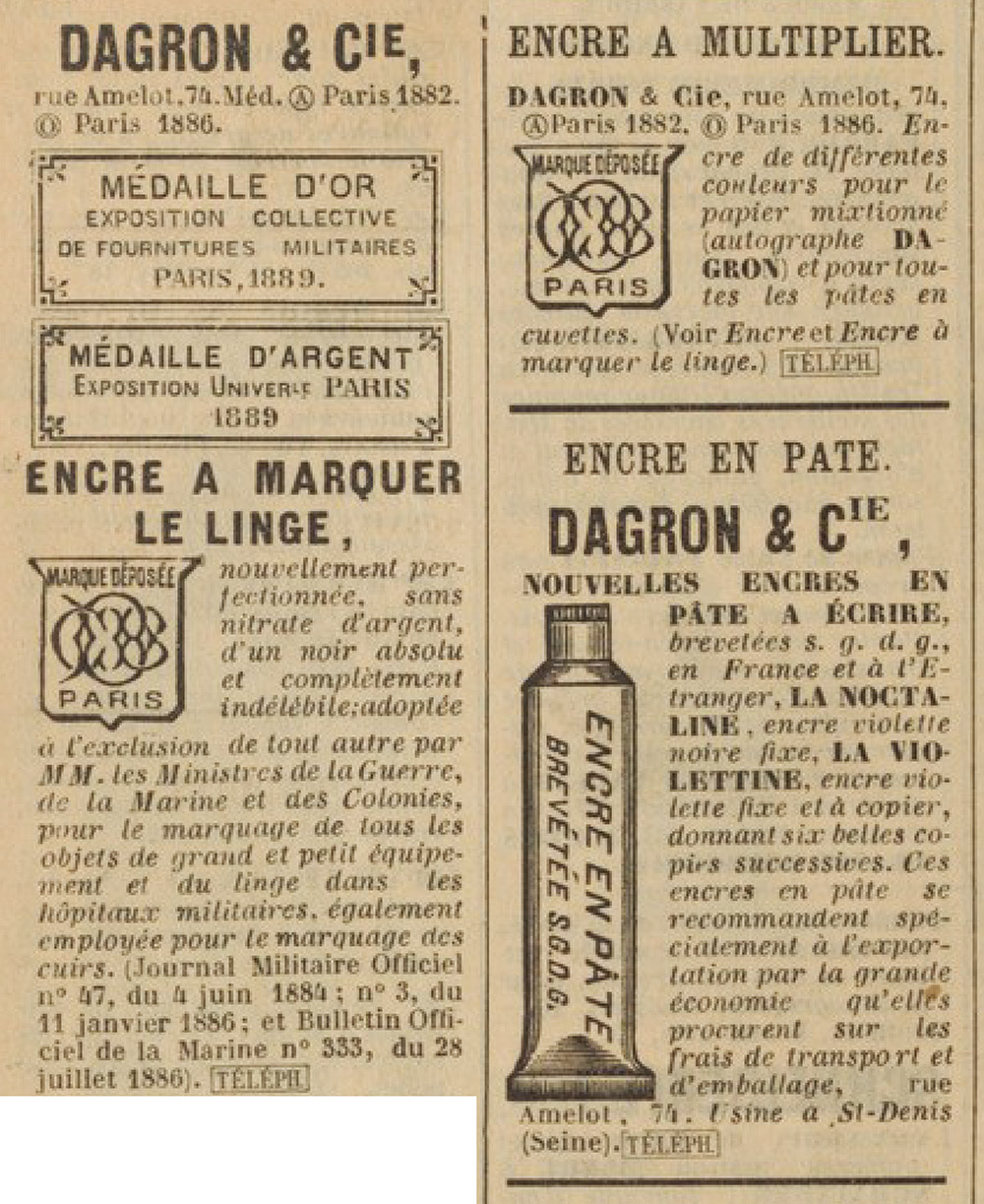

Figure 18.

1891 advertisements for Dagron’s inks and related items, from “Annuaire et Almanach du Commerce, de l'Industrie, de la Magistrature et de l'Administration”.

Figure 19.

Ink bottle from Dagron et Cie. The label indicates production after Dagron’s death. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Figure 20.

1902 advertisement from Dagron and Company, from “Annuaire de l'Armée Française”.

Figure 21.

1907 advertisement for typewriter ribbon, from “Typewriter Topics”.

Figure 22.

A container for Dagron & Co. typewriter ribbon. An illustration on the bottom shows that the business had an extensive factory for producing their inks and other writing supplies. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Acknowledgement

Thank you to histoiredumicroscope.com for generously sharing images.

Resources

L'Aerophile (1900) Obituary of P.R.P. Dagron, Vol. 8, pages 82-84

Annuaire et Almanach du Commerce, de l'Industrie, de la Magistrature et de l'Administration (1861) Dagron et Cie., page 598

Annuaire et Almanach du Commerce, de l'Industrie, de la Magistrature et de l'Administration (1872) Dagron et Cie., page 1268

Annuaire et Almanach du Commerce, de l'Industrie, de la Magistrature et de l'Administration (1875) Dagron et Cie., page 1311

Annuaire et Almanach du Commerce, de l'Industrie, de la Magistrature et de l'Administration (1876) Dagron et Cie., pages 223 and 1368

Annuaire et Almanach du Commerce, de l'Industrie, de la Magistrature et de l'Administration (1882) Dagron et Cie., page 758

Annuaire et Almanach du Commerce, de l'Industrie, de la Magistrature et de l'Administration (1883) Dagron et Cie., pages 261 and 1131

Annuaire et Almanach du Commerce, de l'Industrie, de la Magistrature et de l'Administration (1897) Dagron et Cie., page 351

Annuaire et Almanach du Commerce, de l'Industrie, de la Magistrature et de l'Administration (1898) Dagron et Cie., page 321

Annuaire de l'Armée Française (1902) Advertisement for Dagron et Cie., page 78

Bellier de la Chavignerie, Emile (1863) Manuel Bibliographique du Photographe Français “Cylindres photo-microscopiques montés et non montés sur bijoux, brevetés en France et à l'étranger, par M. Dagron (1862), Prudent René-Patrice Dagron (1819-1900), Paris : rue Neuve-des-Petits-Champs, 66 , 1862”, A. Aubry, Paris, page 17

Causeries Scientifiques (1863) Photographie microscopique, Vol. 2, pages 27-34

The Commissioners of Patents' Journa1 (1861) “René Prudent Patrice Dagron, of 66, Rue Neuve des Petits Champs, Paris, represented by G. Capuccio, Turin, for 'An optical apparatus for obtaining a double view of microscopic photographs.' -6 years.--Dated 24th August, 1861”, Commissioners of Patents (Great retain), page 1595

Dagron, Prudent René Patrice (1864) Traité de Photographie Microscopique, Dagron, Paris

Dagron, Prudent René Patrice (1871?) La Poste par Pigeons Voyageurs, Dagron, Paris

Joanne, Adolphe (1867) Photography, The Diamond Guide for the Stranger in Paris, L. Hachette and Co., London, page 43

Exposiçao Internacional do Porto en 1865: Catalogo Official (1865) Dagron et Cie., pages 16 and 50

French vital records, accessed through ancestry.com

The Journal of the Photographic Society of London (1865) page 168

Journal of the Royal Microscopical Society (1887) Dagron’s microphotographic apparatus, pages 487-488

Les Mondes Revue des Sciences et de Leurs Applications aux Arts et à l'Industrie (1867) Vol. 12, page 402

Moigmo, François Napoléon Marie (1864) "Tubes, bijoux et pierres photo-microscopiques; stéréoscopes, et bioscope à images microscopiques de M. Dagron, 66, rue Neuve-des-Petits-Champs", Cours de Science Vulgarisée, E. Giraud, Paris, pages 62-69

Les Nouveautés photographiques Annee (1901) Prudent Dagron et un point de l’histoire de la photographie, pages 1-9

Paris-Exposition ou Guide à Paris (1867) “Dagron, r. Neuve-des-Petits-Champs, 66”, page 456

The Photographic News (1863) The International Exhibition, page 227

The Quarterly Review (1875) Ballons and voyages in the air, Vol. 139, pages 105-138

Rapports du Jury International (1889) Medailles d’Argent, "MM. Dagron et Cie, fabricants d'encre, rue Amelot, 74, à Paris", Vol. 2, page 210

La Science illustrée (1900) Prudent Dagron, page 124

Typewriter Topics (1907) Advertisement for Dagron et Cie., page 241