Charles Pumphrey, 1819-1901

by Brian Stevenson

last updated September, 2019

Despite

the professional appearance of his slides (Figure 1), Charles Pumphrey appears

to have been purely an amateur microscopist. He was a successful industrialist,

which evidently provided him with the time and financial resources to produce

good quality microscope slides with custom-printed labels. A fair number of his

slide bear labels on which a description of the specimen was type-set (Figure

1). This apparent extravagance suggests that Pumphrey may have produced

multiple copies of some slides, possibly for sharing with colleagues. He was a

life member of the British Association for the Advancement of Science

(beginning in 1841), and a long time member of the Ray Society and the

Birmingham Natural History and Microscopical Society. He was the President of

the latter organization’s Biological Section from 1889 until 1897. As such, he

was closely associated with many notable professional and amateur microscope

slide preparers, including Herbert W.H. Darlaston, James W. Neville and Richard Hancock.

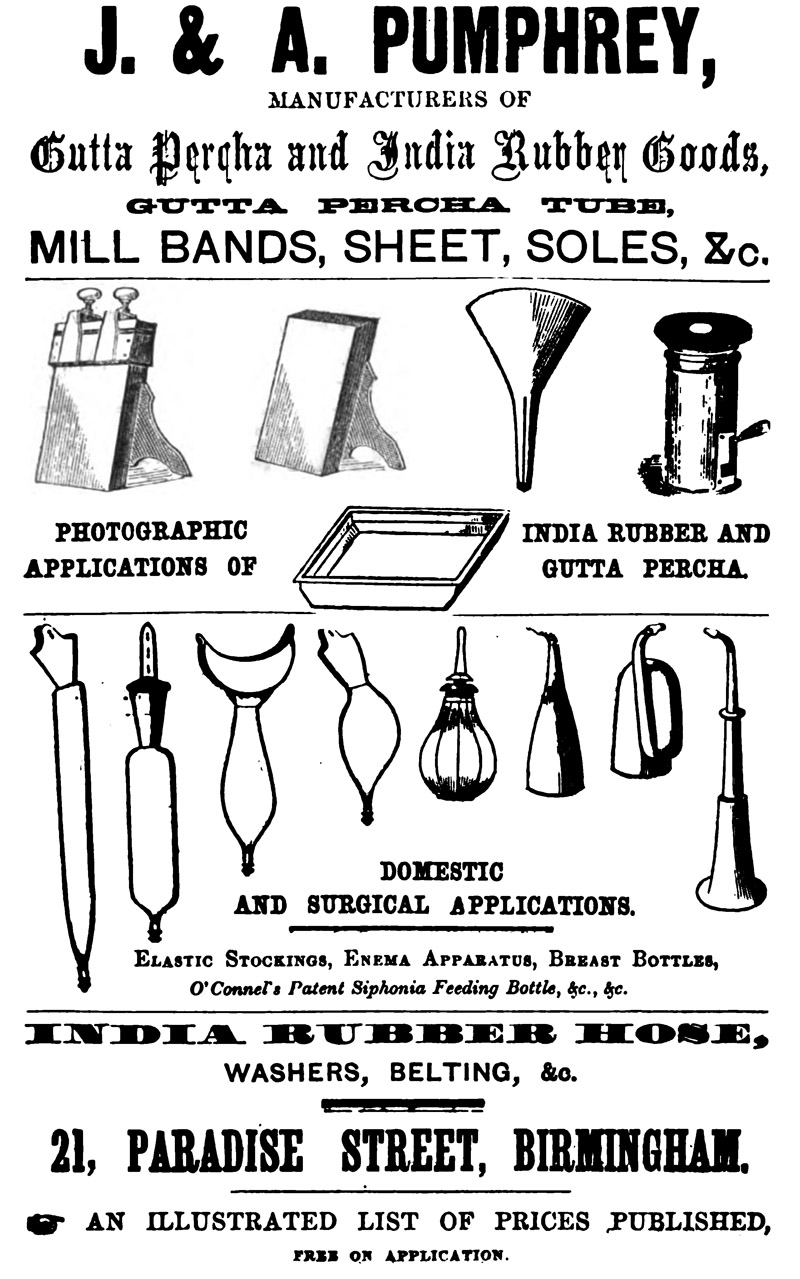

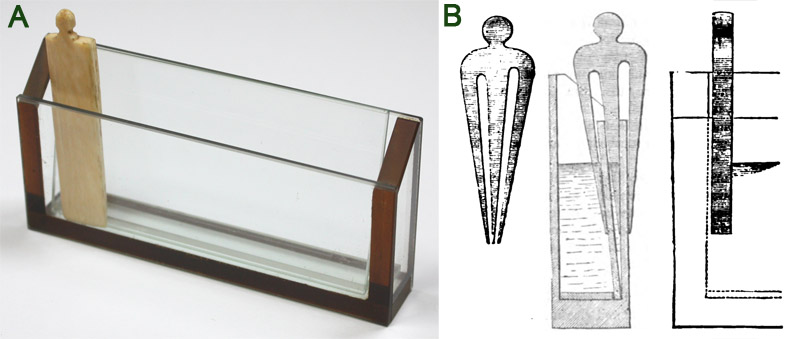

Figure 1.

Examples of Charles Pumphrey’s microscope slides. He

mounted a wide variety of specimen types. Although his custom-printed labels

look professional, there is no evidence to suggest that he sold any of his

preparations. The fluid mount of human fetal intestine used a finely beveled

glass square, approximately 1 mm deep. Other, essentially identical fluid

preparations by Pumphrey are known, suggesting that prepared these himself. It

is possible that he purchased the beveled glasses.

Charles

had close business and social ties with his three brothers, Josiah (1823-1911),

Samuel B. (1826-1912) and Alfred (1830-1913). Josiah was also a member of the

Birmingham Natural History and Microscopical Society. Alfred became a

professional photographer, Josiah produced novel technologies for photography,

and Charles was frequently noted in records for presentations of his

photographs and use of his personal lantern slide projector. Due to their many overlaps, it is often difficult to determine which “Mr. Pumphrey” is being referred to in historical documents. As a further note, there are no known relationships with the noted Victorian photographer William Pumphrey, who lived in York, England.

The four

boys’ father, also named Josiah (ca. 1781-1861) owned a brass foundry. By

mid-century, a rubber factory was added to the family portfolio. Charles and

Samuel inherited the brassworks, while Josiah and Alfred acquired the rubber

factory. Two rubber products proved to be useful for microscopists, as detailed

following. While these were productions of the Josiah/Alfred factory, it is

likely that avid microscopist Charles had a hand in their development.

Their most significant rubber products for microscopy were rings, for use as mounting cells (Figure 2). These were variously described as rubber, vulcanite and ebonite.

Mr. J.E.

Turner wrote to Hardwicke’s

Science-Gossip in 1869, “I have

lately had a supply of Vulcanite Cells from Messrs. Pumphrey,

of Birmingham, and I can safely say they are the best cells that I have

used for mounting objects, dry or in fluid, being far superior to tin or glass

cells, as in change of temperature there is no give in glass or tin, and the

cement cracks; but here we have a substance in every way suited to the wants of

the Microscopist, as the cells can be had in various sizes, as slides 3x1,

perforated with any sized holes, and also as discs to mount opaque objects on,

or to act as a stop to the Lieburkuhn. I have until lately used cells made of

the vulcanized rubber, but these had some disadvantages which are overcome by

The Vulcanite Cells. I find, in cementing them to the glass slide, a scratch

with a fine file on the polished surface causes the marine glue to hold very

firm, and also the top side when cementing down the glass cover; they can also

be ground down to any thickness required by reducing them with a file first,

and finishing off on a flat surface to obtain the cell perfectly level to

receive the glass cover.”

Henry Pocklington (1842-1913), a noted microscopist and writer on the subject,

wrote to The English Mechanic and World of Science, in 1870, “Petals of flowers are rarely capable of presence if their colour is not sufficiently persistent. Those of pelargonium petals may be stripped off, on a glass slip; and mounted in Balsam-potass with them. Thick objects require a cell, which may be glass, wood, vulcanite, or of almost anything. For dry objects cells cut from thick card answer the job

admirably. A common gunwad punch serves to cut them out. I have of late used Pumphrey’s vulcanite cells for all purposes; they are cheap and efficient. Wings of insects rarely require any medium. Wings of Lepidoptera should be mounted dry; ‘opaques’ of Diptera, Neuroptera, and Hymenoptera are also dry‘transparents’.”

Also that

year, R.H. Moore wrote to Hardwicke’s

Science-Gossip, “Your correspondent

has omitted to notice the Vulcanite Cells which are

now used by many microscopists in preference to any other form of cell. They

are fastened to the slide by marine glue, and are perfectly free from leakage.

They can be obtained of any thickness from Mr. S.A. Pumphrey (sic), 21, Paradise-street, Birmingham,

who sends 100 assorted to any address for thirteen stamps.” This letter,

and that of Mr. Turner, sound suspiciously like they were solicited by the

Pumphreys, taking advantage of the popular magazine’s policy of free

publication for letters of advice, etc. Many other businesses finagled free

advertising in such a manner.

Nonetheless,

Pumphrey’s vulcanite cells made a strong, lasting impression among slide

makers. The highly esteemed professional mounter Frederick Enock stated that he

used only those cells. He also developed an improvement, described in this 1881

letter to The Northern Microscopist,

“I have had much bitter experience with

preparations mounted in glycerine, which suffer injury from clumsiness in

handling, more than the fault of expansion; for after a preparation has been

mounted two or three years, the cement becomes very hard, and if injured by a

fall, or knock against the microscope, starts a leak. The number of

preparations ruined by my customers in this and other ways, prompted me to find

a remedy, or to lessen the chance of injury. I have now devised the metal caps,

which so far have stood the heavy thumps of the Post-office men, and all the

clumsy treatment which many give them. The caps are

made to fit Pumphrey's vulcanite cells, as they are

the only cell to be depended upon for size and shape. I never use any other. My

plan of using these caps is as follows: After having fixed the cover properly

and without leakage, I wash the preparation under the tap until all traces of

glycerine are removed, then run a good thick ring of any kind of cement round

the edge of the cover and cell, finally dropping on the cap, when the mount

should be placed aside for a week, so that the cement or varnish may properly

set. I use these caps for all deep cells, as they prevent the cover from being

pushed off, and am having some made half the depth of those sent, for shallow

cells.” Enock then painted over the metal caps, leaving a uniform smooth

black appearance. Pumphrey’s rubber cells are visible from the underside of many of

Enock’s deep mounts, and his metal caps may be visible on slides in which the

black paint is chipped or worn (Figure 3).

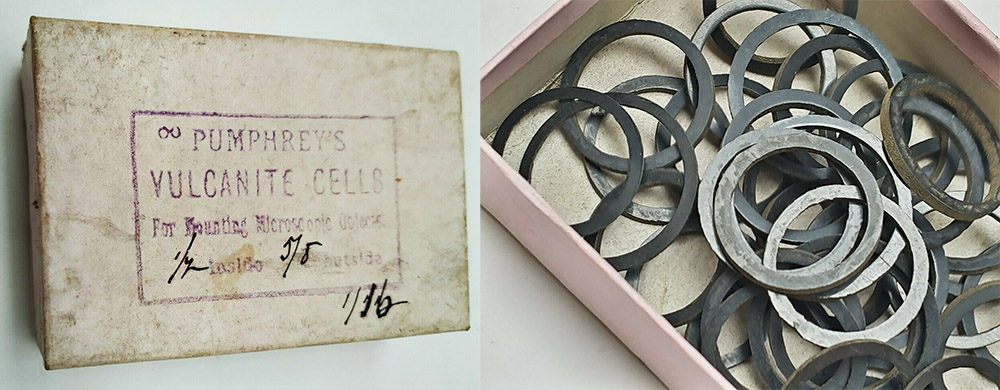

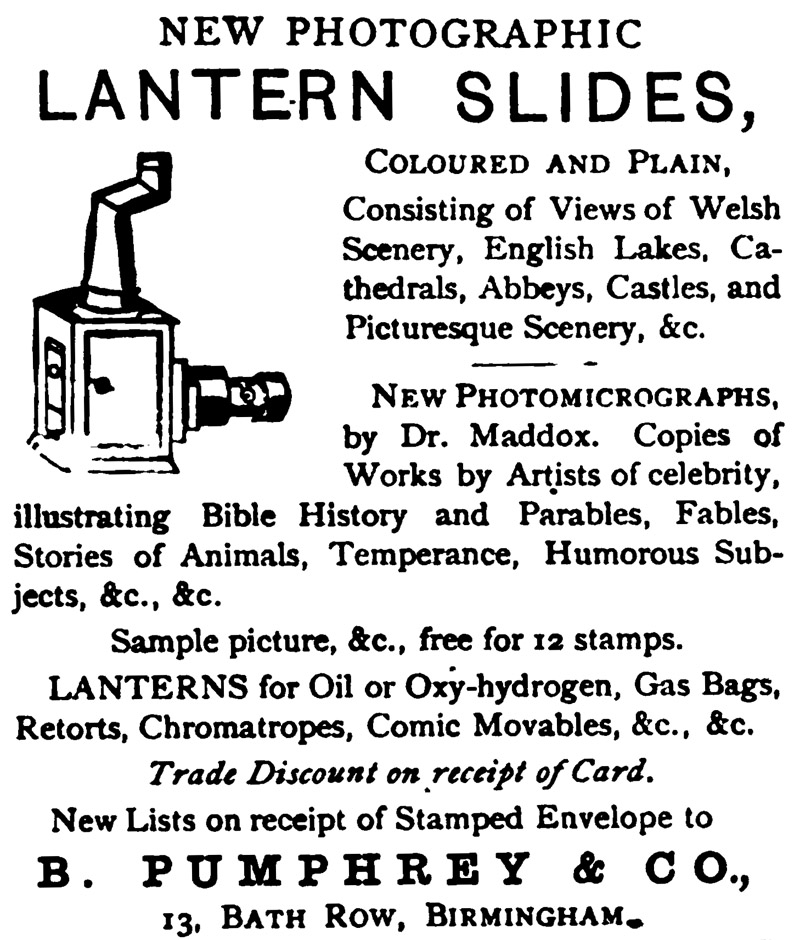

Figure 2.

A box of Charles Pumphrey's "Vulcanite Cells" for use in slide-making. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

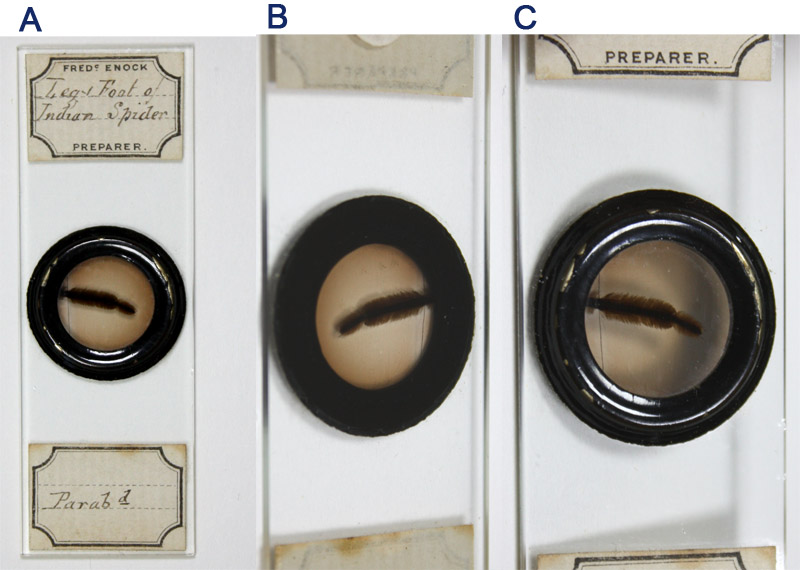

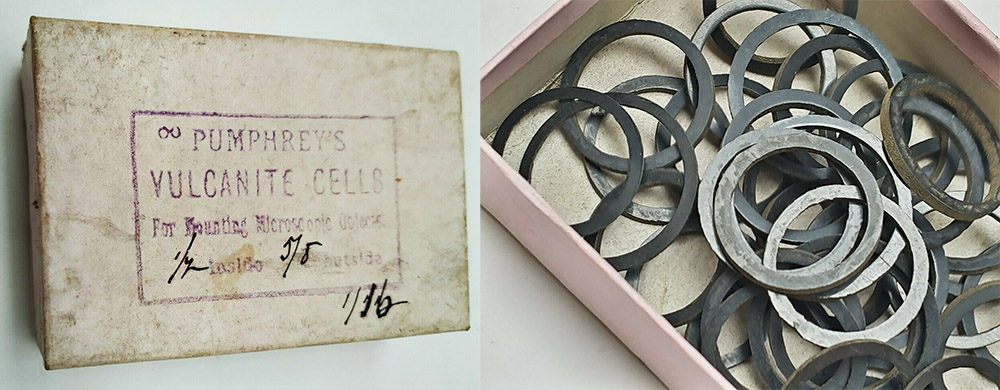

Figure 3.

(A) “Leg

and foot of Indian spider”, by Frederick Enock.

(B) Rear view, showing a Pumphrey’s vulcanite cell. The black

rubber can be difficult to discern from the black paint.

(C) The metal cap used by Enock to protect the ring from being

dislodged is visible where paint has been worn away. The metal appears to be brass.

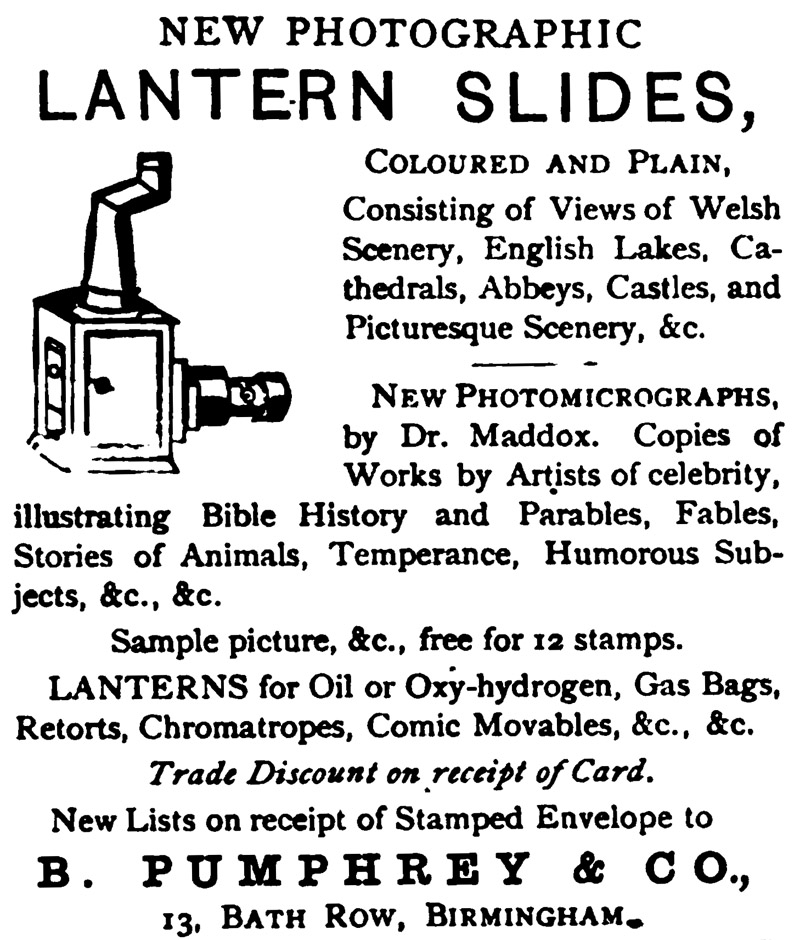

The

Pumphreys’ second aid to microscopists was an improved wedge for the “zoophyte

trough” (Figure 4). W.P. Marshall, a member of the Birmingham Natural History and Microscopical Society, wrote to Hardwicke’s

Science-Gossip in 1867:

“In the ordinary zoophyte trough used for

examining under the microscope animal or vegetable objects in water in a free,

unconfined condition, the position of the inclined glass plate is regulated by

an ivory wedge in front, supported by a whalebone spring at the back inside the

trough; but this construction has the objection that the spring is liable to be

upset sideways by an accidental touch of the hand, or by catching the stage

bracket of the microscope, causing the object in view at the time to be

suddenly washed out of the field and perhaps lost altogether, to the

disappointment of the observer.

For the purpose of removing this objection, I have

devised, in conjunction with Mr. Pumphrey, a double clip that takes the place

of the wedge and spring, and is found very satisfactory and convenient, and

quite free from risk of disturbance accidentally. This clip is shown full size

in the accompanying drawing, and is made of a piece of ebonite about one-eighth

of an inch thick, having two long cuts upwards from the bottom end, inclined to

one another so as to leave a wedge-shaped piece between them, corresponding to

the ordinary wedge for regulating the position of the inclined glass plate;

whilst the front and back portions act as spring clips, holding the front plate

of the trough and the inclined plate, the two cuts in the clip being made narrower

at the bottom end than the thickness of the glass plates, so as to hold them by

a slight spring pressure, as shown in the detached view of the clip.

By sliding this clip up or down, the width of the

space between the plates that contains the objects under examination, is

regulated in the same manner as by the ordinary wedge; and the clip at the same

time holds the inclined plate securely in each position, without any risk of

being displaced or moved unintentionally, as the clip is entirely free from the

back of the trough, and keeps clear of the stage bracket in all positions

whilst the trough is being moved upon the microscope stage.

The narrowness of this clip is also an advantage, as

the ordinary wide wedge occupies an inconvenient amount of the field of view.

The inclined glass plate, which is usually made as

high as the back of the trough, is cut down in this case to the same height as

the front of the trough, as this is found to be a sufficient height, and allows

the clip to be shorter.

A specimen of these clips is enclosed herewith, and

they are now made by Mr. Pumphrey, Paradise Street, Birmingham, from whom they

can be obtained. In the drawing the larger of the two sizes of zoophyte trough

in ordinary use is shown, but the same clips suit also the smaller size of

trough, and in that case the original height of the inclined glass plate is not

altered.”

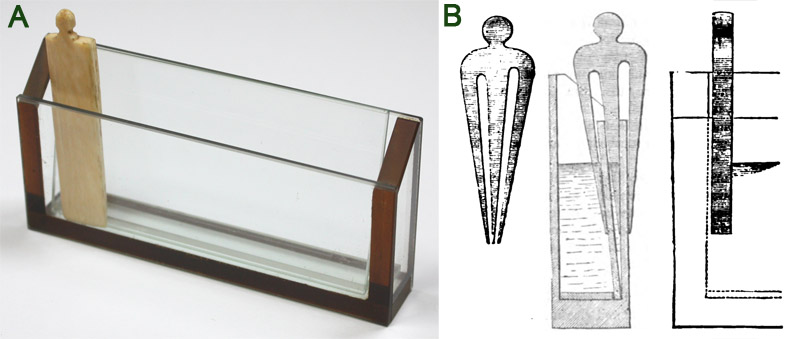

Figure 4.

(A) A Victorian-era zoophyte trough. The glass trough

measures about 3 inches wide. A glass slip fits loosely inside the trough. A

spring, which is absent from this example, would press the glass slip against

the front of the trough, while an ivory wedge would hold the slip slightly away

from the trough front. Thus, microscopic objects in a water sample could be

compressed into a thin area for viewing under the microscope.

(B) Marshall and Pumphrey’s 1867

improved wedge, which was a rubber clip that held both the trough’s front and

the moveable glass slip, eliminated the need for a rear spring.”

Charles

Pumphrey was born June 19, in Worcester, England. During 1823-24, the family

moved to Birmingham, Warwickshire. The 1841 census shows the Pumphreys living

on New Town Row in the St. George parish. Josiah was recorded as being a “brass founder”, as was also 21 year-old

Charles. At some point during the following 7 years, Charles became a partner

in the business with his father. Josiah was awarded a patent in 1847 “for certain improvements in machinery to be

employed in the manufacture of wire hooks and eyes”. Production of hooks

and eyes was the major product of the Pumphreys’ brassworks through the

remainder of the century, although they were also noted as producers of brass

nails in 1848.

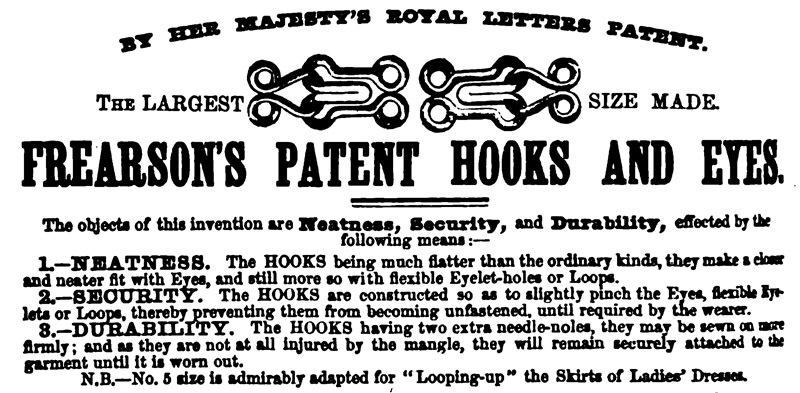

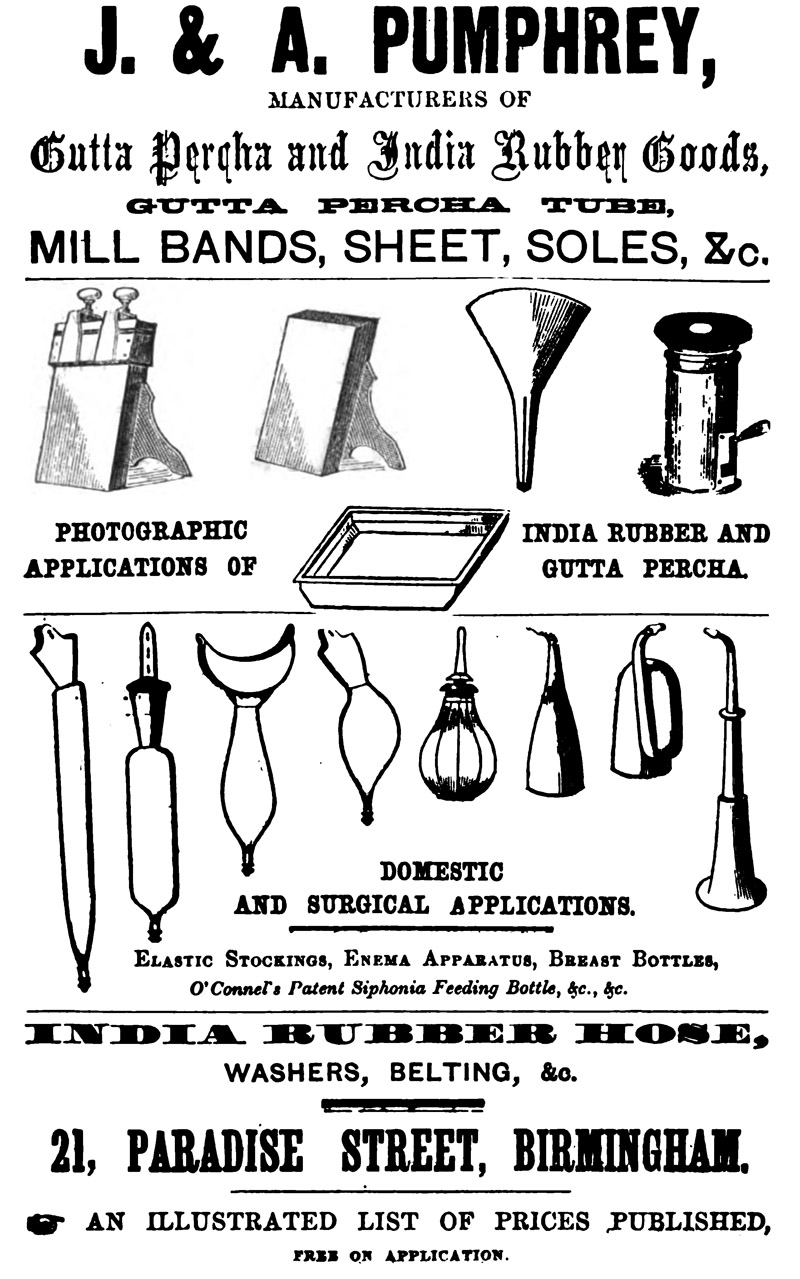

Figure 5.

An 1861 advertisement from another Birmingham

brassworks, shown to clarify the meaning of “hooks and eyes”. I have not

located any advertisements from the Pumphrey businesses. Hooks and eyes were

the primary means for closing women’s’ dresses and other garments, filling the

role occupied today by the zipper. Brass was preferred for this, as it is strong

yet does not rust.

The

Pumphrey brass business evidently fell on hard times in the late 1840s. In

1848, “Pumphrey, J. and C. brass founders and nail manufacturers, Birmingham” was assigned for

benefit of creditors. This appears to have led to reorganization of the

business. The 1851 census recorded Josiah as being a “commercial clerk”. Charles still lived with his parents and most of

his siblings, and was listed as “hook

& eye maker, master, (employs) 17 persons”. On June 30, 1852, Charles

Pumphrey married Emma Palmer.

By 1861,

the family business had diversified to also include rubber manufacturing, with

two brothers operating the brass foundry, and the other two, the rubber

business. An 1861 directory of Birmingham listed “Pumphrey, Charles and Samuel B., manufacturers of hooks and eyes, &c, 40 1/2,

Mount street” and “Pumphrey, Josiah and Alfred, gutta

percha and India rubber manufacturers, and

importers of overshoes, &c., 21, Paradise street, and at 42 1/2, Edmund

street”. In addition, Alfred was operating a photography business from his

home. Father Josiah died in May, 1861, leaving an estate of less than £300.

Presumably, his boys, who all appear to have had successful businesses,

received their father’s wealth before he died.

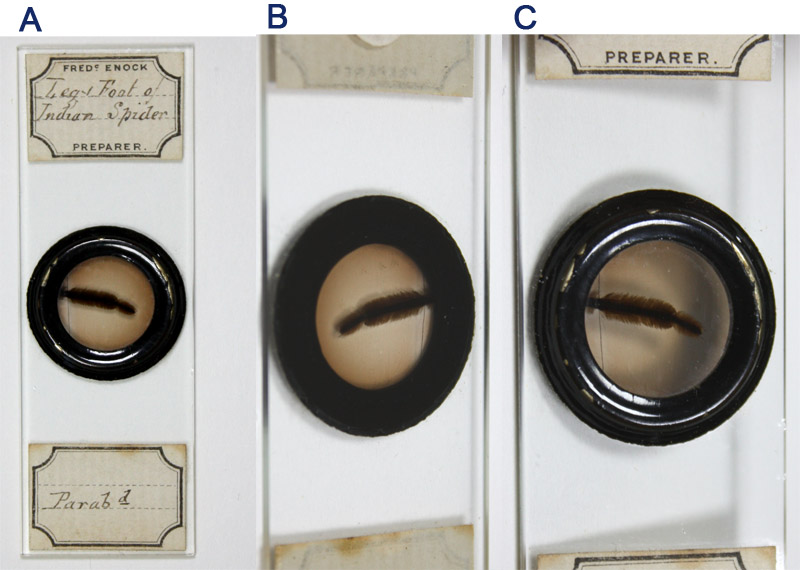

Figure 6.

An 1861 advertisement for Josiah and Alfred

Pumphrey’s rubber company. Their foundry supplied the vulcanite microscope

cells and zoophyte trough clips illustrated in Figures 1-3, above. From the

Corporation General and Trades Directory of Birmingham.

In 1867, Charles

and Samuel also began a rubber manufactory, which Samuel eventually took it over

completely in 1877. As later described in the Illustrated Guide to the Cork International Exhibition of 1883, “The Ladywood Works were founded in 1867 by

Mr. S.B. Pumphrey, for

the production of Rubber goods suited for machinery and the general use of

manufacturers. A year later the Company was formed, and a rapidly progressive

business commenced. The articles made by the Company include driving belts for

machinery, engine and air-pump valves, steam washers, water hose, gas tubes,

bicycle tyres and pedal rubbers, etc.”

Another

business developed during the mid-1860s. “Pumphrey Brothers” sold lantern

projectors, lantern slides and assorted other photography and projection

apparatus and supplies. A later advertisement from Alfred indicated that he was

part of the Pumphrey Brothers. Charles had a strong interest in photography, frequently

presented slide shows of his own photographs with his own projector, so Charles

may have been another partner in that venture. The business ended by 1876, as

advertisements from Alfred that year described him as “late Pumphrey Brothers”.

Figure 7.

An 1869 advertisement from the Pumphrey Brothers

(“B. Pumphrey”). Charles may have been a partner in this business. Among their

wares, the Pumphreys sold the celebrated photomicrographs of Richard Maddox.

The

rubber-making partnership of Josiah and Alfred was dissolved in 1873, “Camp-hill Works, Emily-street, India-rubber manufacturers. Josiah Pumphrey, Alfred Pumphrey. Debts received and paid by

Josiah Pumphrey, who will in future carry on the

business. 3rd June 1873”. Alfred then worked full time in photography.

Charles

and Samuel’s partnerships were dissolved in 1877, with Charles taking the

brassworks, and Samuel the rubber business, “Notice is hereby given, that the Partnership heretofore subsisting

between us the undersigned, Charles Pumphrey and Samuel Baker Pumphrey, carrying on business at 89, 90, and 91,

Ryland-street North, Birmingham, in the county of Warwick, under the style or

firm of C. and S.B. Pumphrey, as Hook and Eye Manufacturers, has this day been

dissolved, by mutual consent; and notice is given, that all debts due to and

owing by the said late partnership will be respectively received and paid by

the said Charles Pumphrey, by whom the said business will in future be carried

on. Dated the 29th day of March, 1877. Charles Pumphrey, Saml. B.

Pumphrey”, and “Notice is hereby

given, that the partnership heretofore subsisting between us the undersigned,

Charles Pumphrey, Samuel Baker Pumphrey, and Samuel Price, carrying on business

at 89, 90, and 91, Ryland-street North, Birmingham, in the county of Warwick,

under the style or firm of the Midland India Rubber Company, has this day been

dissolved, by mutual consent, so far as regards the said Charles Pumphrey; and

notice is given, that all debts due to and owing by the said late partnership

will be respectively received and paid by the said Samuel Baker Pumphrey and

Samuel Price, by whom the said business will in future be carried on under the

same style as heretofore. Dated the 29th day of March, 1877, Charles

Pumphrey, Saml. B. Pumphrey, Samuel Price”,

Charles’

wife, Emma, died May 2, 1881. Her obituary in The British Friend indicated that the Pumphreys were Quakers.

Charles remarried on April 1, 1884, to Marion deCastley. Marion died October

24, 1898. Charles married a third time, in mid-1900, to the much-younger Alice

Gertrude Rogers. The 1901 census recorded the household at 5 Park Road, King’s

Norton as containing retired 81 year-old Charles, 47 year-old Alice, Charles’

43 year-old daughter Laura, and two servants.

Charles

died on September 17, 1901. Alice received both Charles’ and Marion’s estates,

valued at just over £15000. The India Rubber

and Gutta Percha and Electrical Trades Journal reported, “The death occurred at his residence,

Castlewood, Park Road, Moseley .. of Mr. Charles Pumphrey, a

very old citizen of Birmingham, and one who was

highly respected for his quiet, unostentatious work in the cause of social

reform. The deceased carried on business in partnership with his brother, Mr.

Samuel Pumphrey, as a hook and eye manufacturer, at

Regent Works, Herbert Road, Small Heath. He was a man of considerable

mechanical knowledge and skill, and was the inventor of a labour-saving machine

which proved of great importance to the industry. For a considerable period he

was associated with his brothers in the rubber trade, their business in Ryland Street being taken over some time since by the

Midland Rubber Company.”

Resources

Birmingham Commercial List (1874) Dissolution of the partnership of J. and A. Pumphrey, Estell and Co.,

London, page 11

Bracegirdle,

Brian (1998) Microscopical Mounts and

Mounters, Quekett Microscopical Club, London, pages 77 and 164, and plate

30, slides J and K

The British Friend (1881) “Deaths .. At Southfield, King’s Norton, near

Birmingham, Emma, wife of Charles Pumphrey, in her 62nd year”, Vol. 39,

page 5

The British Friend (1884) “Marriages .. At St. Philips, Birmingham,

Charles Pumphrey, of King’s Norton, to Marion de Castley. No cards”, Vol.

42, page 89

Corporation General and Trade Directory of Birmingham (1861)

William Cornish, Birmingham, pages 272, 466, 471 650 and 666, and advertising

section

England

census, birth, marriage and death records, accessed through ancestry.co.uk

Harrison,

William J. (1890) “Photography can

admirably record every twig and leaf. It is certain that good photographs of

plants, especially if taken while growing in their native haunts, would help to

vivify the dry leaves of herbaria, and they would be much valued by those who

study and teach botany. I have seen some exquisite work in this direction done

by one of our members, Mr. Charles Pumphrey”, Notes upon a

Proposed Photographic Survey of Warwickshire, Birmingham Photographic

Society, Birmingham, page 16

Hartnell,

H.C. (1883) Illustrated Guide to the Cork

International Exhibition, Guy Brothers, Cork, page 126

The India Rubber and Gutta Percha and Electrical Trades

Journal (1901) Obituary of Charles Pumphrey, Vol. 22, page 261

Law Times (1848) “Assignments. For the Benefit

of Creditors .. July 28. Pumphrey, J. and C. brass founders and nail

manufacturers, Birmingham”, Vol. 11, page 407

London Gazette (1877) Dissolution of the

partnerships between Charles and Samuel Pumphrey, April 20, page 2540

Marshall,

W.P. (1867) Clip for zoophyte trough, Hardwicke’s

Science-Gossip, Vol. 3, page 105

The Midland Naturalist (1889) “Birmingham Natural History and Microscopical

Society – General Meeting Jan. 29th .. Mr. C. Pumphrey and Mr. C. J. Watson exhibited by the aid of

the oxyhydrogen lantern a large number of photographic views of objects and

places of interest in Switzerland, Italy, the Channel Islands, Weymouth, Bath,

and of the recent beautiful hoar frost on leaves and trees in this district,

which were much appreciated by the meeting, and a hearty vote of thanks was

passed to them”, Vol. 12, page 71

The Midland Naturalist (1890) “Birmingham Natural History and Microscopical

Society – Geological Section, March 18th, A paper on Norway and the North Cape

was read by Mr. W. P. Marshall, M.I.C.E., and illustrated by the oxy-hydrogen

lantern by Mr. Charles Pumphrey. There was a very

large attendance, the accommodation of the Examination Hall, Mason College,

being taxed to the uttermost. A hearty vote of thanks was given to Messrs.

Marshall and Pumphrey”, Vol. 13, page 94

Moore,

R.H. (1870) Vulcanite cells, Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip, Vol. 6, page 20

Perry & Co.’s Monthly Illustrated Price Currant (1876) Advertisement from Alfred Pumphrey, Dec. 5, page 44

Pharmaceutical Journal (1875) “Soirée of the Midland Counties Chemists’

Association .. was held in the Town Hall on Thursday evening, Feb. 4th, and was

attended by nearly four hundred persons .. At half-past

eight o'clock the soirée opened with a

lecture by Mr. Josiah Pumphrey, who used limelight illustrations. Dancing

commenced at about halfpast nine”, Vol. 5, page 668

Pocklington, Henry (writing as "H.P.") (1870) Mounting microscopic objects, English Mechanic and World of Science, Vol. 11, page 476

Pritchard, Andrew (1847) “6169. J Pumphrey, Birmingham, brass-founder, for certain improvements in machinery to be employed in the manufacture of wire hooks and eyes. Nov. 2”, English Patents, Whittaker & Co., London, page 405

The Photographic News (1888) “Birmingham Photographic Society .. Charles

Pumphrey .. read his paper on Stereoscopic Pictures from Film Negatives, and

exhibited a number of the same in the stereoscope taken by him on films in

Switzerland. His explanation and description of the process proved of great

interest to the members present. In the discussion which followed, C Pumphrey

said the great bar to taking stereoscopic pictures with amateurs was the

extreme care and exact manipulation required”, Vol. 32, page 350

Post Office Directory of Birmingham (1879)

pages 131, 189, 394, 524 and 527

Probate of

Josiah Pumphrey (1861) “The will with a

codicil of Josiah Pumphrey formerly of Lee-crescent Birmingham but late of 4

Lodge-road All Saints Birmingham in the County or Warwick deceased who died 6

May 1861 at Lodge-road aforesaid was proved at Birmingham by the affirmation of

Rebecca Pumphrey of 4 Lodge-road aforesaid Widow the Relict and the sole

Executrix. Probate being granted under certain Limitations. Effects under £300”,

accessed through ancestry.co.uk

Probate of

Marion Pumphrey (1898) “Pumphrey Marion

of 5 Park-road Moseley Worcestershire (wife of Charles Pumphrey) died 24

October 1898 at 22 Newhall-street Birmingham Administration Worcester 2 May to

Alice Gertrude Pumphrey widow Effects £1150”, accessed through

ancestry.co.uk

Probate of

Charles Pumphrey (1901) “Pumphrey Charles

of 5 Park-road Moseley Worcestershire gentleman died 17 September 1901 Probate

Worcester 10 January to Alice Gertrude Pumphrey widow and Laura Margaret

Pumphrey spinster Effects £14300 18s 5d”, accessed through ancestry.co.uk

Report of the British Association for the Advancement

of Science (1889) Life Members: 1841,

Pumphrey, Charles

Report

of the Microscopical Section of the Birmingham Natural History Society (1869) “The

objects exhibited during the year, not have been so numerous as formerly, yet

unusually rare, exciting much interest, being from personal capture.. Mr. Charles Pumphrey, Stephanoceros Eichornii, marine Polyzoa

of Genera Alcyonidium and Flustra. Two crustacea captured at Watchett,

Phoxichilidium olivaceum and Pycnogonum littorale, also a collection of palates

of Mollusca”, page 15

Scientific Opinion (1870) “Birmingham Natural History and Microscopical Society,

at the meeting held February 8th, … The following are some of the specimens

exhibited at the meetings … By Mr. C. Pumphrey, some

singular cylindrical bodies from Bulimusacuttus, and stellate hairs of Aralia

papyriera (the Chinese rice-paper plant)”, page 253

Scientific Opinion (1870) “Tuesday, (June) 14th,

Birmingham Natural History and Microscopical Society, 7.30 p.m. ‘On the

Preparation and Mounting of Palates of Mollusca’, by C. Pumphrey”, page 516

Turner,

J.E. (1869) Vulcanite cells, Hardwicke’s

Science-Gossip, Vol. 5, page 139