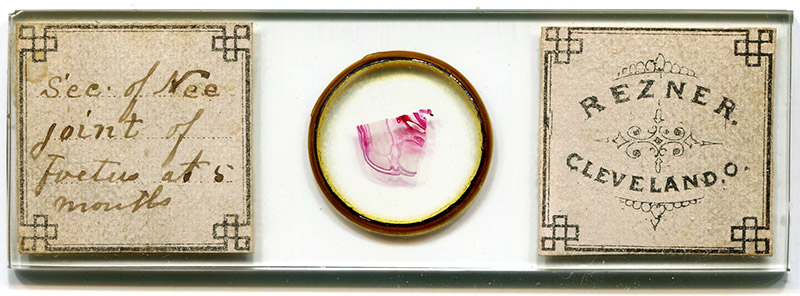

Figure 1. ca. 1870s microscope slide by William Rezner, "section of knee joint of foetus at 5 months".

William Boal Rezner, 1824 - 1883

by Brian Stevenson

last updated June, 2024

William B. Rezner was a physician and surgeon in Cleveland, Ohio, USA. He was also a keen microscopist, being a member and officer in the American Society of Microscopists and his local Cleveland Microscopical Society.

In line with his profession, Rezner prepared many slides of histological and pathological specimens (Figures 1 and 2). A colleague wrote that “his mounting of slides was not excelled by any of the specialists in that line”.

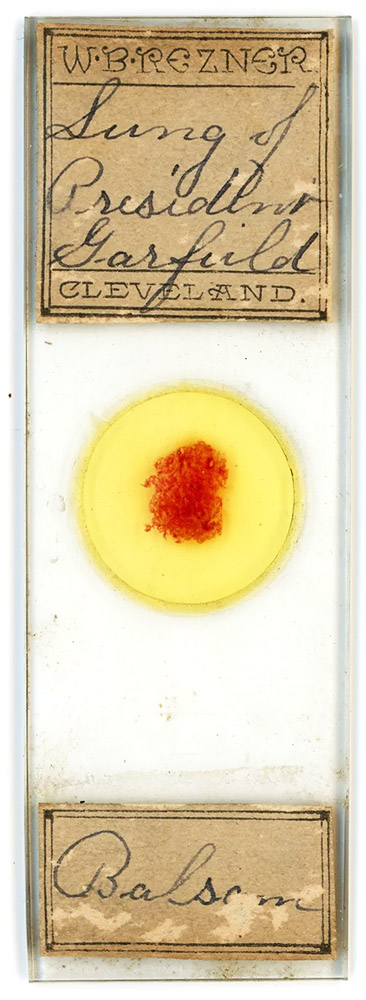

Rezner was also interested in the structures of diatom frustules. To aid his work in selecting and arranging diatoms, he invented a mechanical “finger” (Figure 3). “Dr. Rezner’s mechanical fingers” were manufactured and sold by several retailers into the twentieth century (Figure 4).

Figure 1.

ca. 1870s microscope slide by William Rezner, "section of knee joint of foetus at 5 months".

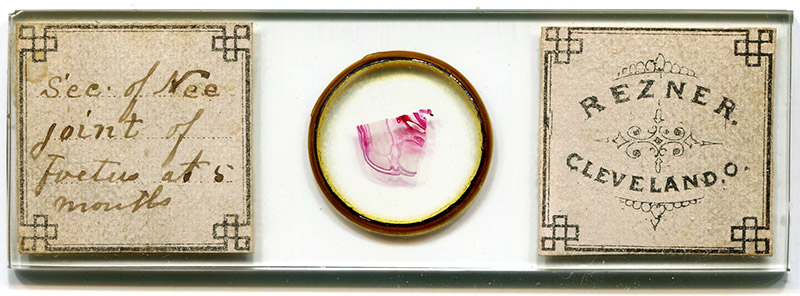

Figure 2.

Another labeling style of William Rezner. This curious slide holds a section of lung from assasinated U.S. President James Garfield, who was shot on July 2, 1881. The history of this slide is described on https://antiqueslides.net/president-james-garfield-assassination-purolined-lung/. Image adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes.

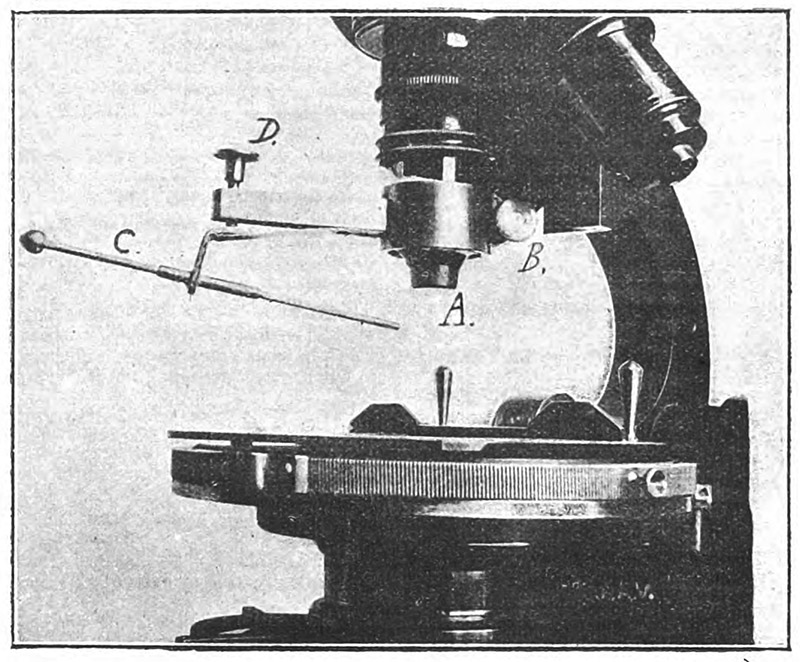

Figure 3.

“Dr. Rezner’s Mechanical Finger”, engraving from Jabez Hogg’s “The Microscope”, 1883 edition. His friend and colleague Charles M. Vorce described it in 1879: “the sleeve, seen in the figure, is passed up on the objective far enough to have firm bearing, and so that the bristle point will be in focus when depressed nearly to its limit; it is clamped in place by the small thumbscrew. The wire in which the bristle is carried is drilled at the point to receive it, and slides easily but not loosely through a small sleeve, so that the end of the bristle can be brought into the centre of the field when in focus, and the wire can be revolved so as to view every side of object picked up by the bristle. The wire stands at a greater angle than is shown in the cut, and the vertical part of the spring is not so long as figured. When using the finger the bristle is first raised by the micrometer screw till so far within focus as to be nearly or quite invisible, then the objective is focused on the slide of material and the desired object sought for; when found, it is brought to the centre of the field, and the bristle point is then lowered by the screw till it touches the object, which usually will adhere to it at once, but sometimes several trials may be necessary; when it does adhere to the bristle, the objective is raised clear of the slide, and the object may be examined by rotating the bristle wire by means of its milled head. The object may in many cases be thoroughly examined without lifting it from the slide, by pushing it about with the bristle, or even rolling it to and fro under the bristle, by moving the slide by hand or stage movements…. A diatom or other object having been selected, the bristle point is brought down to it, and when it adheres the point is raised well within the focus, and then the microscope body is racked back a little, the slip of material removed and that bearing the gelatinized cover substituted on the stage; the objective is then focussed on this, and the centre found, when the bristle point is lowered into focus and the object deposited on the cover, and if necessary pushed into its proper position. The bristle is then raised (and until some practice has rendered the operator skilful, it is best also to rack back the objective a little), the slip removed and covered up, the slip of material replaced and the process repeated till the desired arrangement is complete, when the slide should be mounted at once, or accidents will be sure to spoil it. When all the diatoms are in place, breathe gently on the cover several times, warming it between times over the lamp; this fixes the objects in the gelatine and prevents their washing out.”

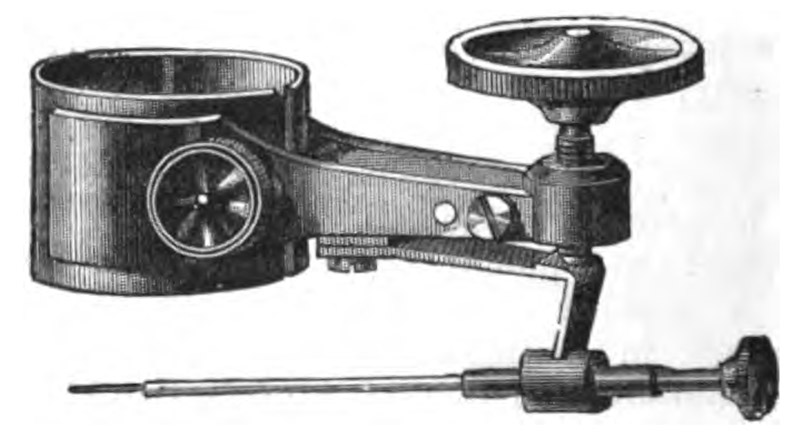

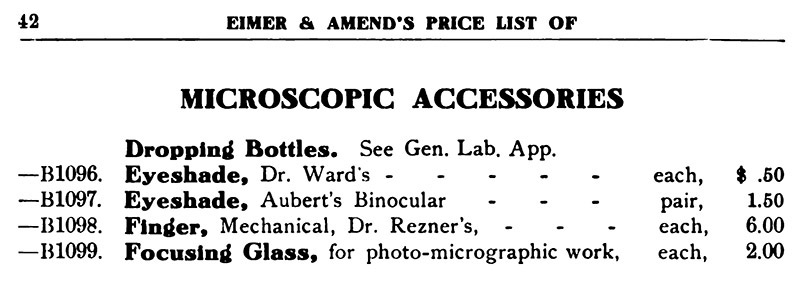

Figure 4.

A Rezner-type mechanical finger, mounted onto a microscope's objective lens. The bristle tip is centered over the field of view. After locating a diatom or other item of interest on a slide of specimens, the lens is racked down so that the tip touches the diatom, which usually adhere to each other. Racking the lens up will lift the diatom. A new slide can be placed onto the stage, the lens racked down, and the diatom transferred to adhesive on the new slide. Image from a 1904 article on the topic by A. Verinder.

Figure 5.

Excerpt from Eimer and Amend’s 1907 “Catalogue of Bacteriological Apparatus”.

William Boal Rezner was born on July 18, 1824, in Miffinsburgh, Pennsylvania, son of John and Mary Rezner. “Boal” was the mother’s maiden name.

Around 1842, when 18 years old, Rezner moved to Mesopotamia, Ohio, in the northern part of the state, not far from Cleveland. He attended Cincinnati Medical College, graduating in 1846. He then opened a practice in Mesopotamia. Also in 1846, William Rezner married Adaline Tracy. The pair had three girls and one boy.

In 1854, the Rezner family moved to Cleveland.

The U.S. Civil War began in April, 1861. In October of that year, William enlisted as surgeon for the 6th Ohio Volunteer Cavalry, and became Chief Surgeon of his brigade. He reportedly saw service around Gettysburg and Richmond. He served until the war ended in 1865.

A friend and microscope colleague, Charles Vorce, wrote about Rezner, “On his return from the army Dr. Rezner resumed the practice of his profession, and with his naturally great skill enhanced by the valuable experience he had gained during his service in the army rapidly recovered the practice he had surrendered, and speedily advanced until he stood in the foremost rank of the most skillful physicians and surgeons of the day, and had he been gifted with more worldly ambition and less retiring modesty he might have won a renown that would have made his name famous, but he had a horror of anything that seemed to him like boastfulness which led him rather to conceal merits, and undoubtedly operated somewhat to prevent in many cases his receiving the credit which was his due. But to those who experienced his skill he seemed infallible, and no physician or surgeon ever enjoyed a more implicit confidence on the part of his patients than did he.”

In contrast, William Corlett, Professor at Western Reserve University and Fellow of the Royal Society of Medicine, wrote, “Dr. Rezner was an army surgeon, a veteran of the Civil War, but who for many years was more interested in the microscope and of studying diatoms than in following the progress of the surgical art.”

Vorce wrote further about Rezner, “His interest in Microscopy was very great and had extended a period of about twenty years, during which so far as he had time he prosecuted unceasingly the study of various problems connected with it, giving great attention to methods of staining and dissection as applied to pathology. Although a great deal of his work was worthy of publication he could not be induced to publish it, and only his friends and associates learned of it from him, though in turn frequently communicated it to others. He was President the Cleveland Microscopical Society at the time of his decease, and stood at the head of microscopists in the city. His mounting of slides was not excelled by any of the specialists in that line ...”

“His best known invention relating to the resolution of tests was the plating of micrometer lines with silver, by which method the difficulty of resolution was so much decreased that one of the best known microscopists described the result as ‘altogether too easy to be interesting’. By this method Dr. Rezner succeeded in resolving the famous band of 120,000 lines to the inch, which resolution he was the first to accomplish, and which he exhibited at the Buffalo meeting of the American Society of Microscopists, and this method has since had extensive application. Dr. Rezner devised and constructed a special traversing apparatus for use in the resolution of lined tests, and among other devices an improved fitting with universal movements for the Wenham reflex illuminator. He personally constructed several different forms of the Wenham reflex illuminator, numerous solid oculars, immersion illuminators, and various prisms and special fittings of many kinds, for use in special investigations in which he was from time to time engaged… Various other forms of microscopical apparatus in common use were modified and improved upon by him ...”

“Sometime previous to his demise, he had completed a spectroscope of his own manufacture, which was so delicate and so fine an instrument that with it the sodium line, D, in the solar spectrum could be resolved and the nickel line seen.”

His interest in microscopy and diatoms led to the invention of his famed mechanical finger (Figures 3 and 4). As with his other inventions, Rezner did not broadcast a description of this apparatus. Vorce wrote of it in 1879, along with a description of his own methods for arranging diatoms into patterns. Examples of Vorce’s work can be seen in the essay of his life and works, elsewhere on this site.

Rezner’s mechanical skills extended to larger scales. He apparently designed part of a bridge in Cleveland.

In the summer of 1883, he “attended his patients as usual up to Sunday, July 15th, when he experienced an attack of angina pectoris, from which, however, he recovered somewhat and during the week even visited one or two of his patients, and on Saturday, July 21st, he had arranged to visit a patient in the afternoon, feeling then much better than he had during the week. He ate dinner on that day as usual, enjoying well, and after dinner lay down for a short rest and evidently must have experienced a sense of oppression as he tried to arise, and falling forward on his face, expired without a struggle."

Figure 6.

“Section of knee joint of foetus at 5 months”, prepared ca. 1870s by W.B. Rezner. Photographed with a 3.5x objective lens and C-mounted digital SLR camera on a Leitz Ortholux II microscope.

Resources

Bausch & Lomb (1896) Microscopes, Microtomes, Apparatus for Photo-Micrography, and Bacteriology Laboratory Supplies, Dr. Rezner's mechanical finger listed on page 196

Corlett, William (1920) Early Reminiscences, Lakeside Press, Cleveland, pages 41-42

Davis, George E. (1882) Practical Microscopy, second edition, D. Gogue, London. description of Rezner’s mechanical finger, pages 293-294

Eimer & Abend (1907) Catalogue of Bacteriological Apparatus, page 42

Hogg, Jabez (1883) The Microscope, G. Routledge and Sons, London, Dr. Rezner's mechanical finger described on page 218

Journal of the Royal Microscopical Society (1879) Rezner’s mechanical finger, pages 951-952

Proceedings of the American Society of Microscopists (1881) Officers of the Society, title pages

US census and other records, accessed through ancestry.com

Verinder, A. (1904) Mechanical finger, English Mechanic and World of Science, Vol. 79, page 154

Vorce, Charles M. (1879) The mechanical finger, The American Journal of Microscopy, pages 65-66

Vorce, Charles M. (1883) A memoir of William B. Rezner, M.D., Proceedings of the American Society of Microscopists, pages 242-245

Vorce, Charles M. (1883) Memorial of William B. Rezner, The American Monthly Microscopical Journal, pages 159-160