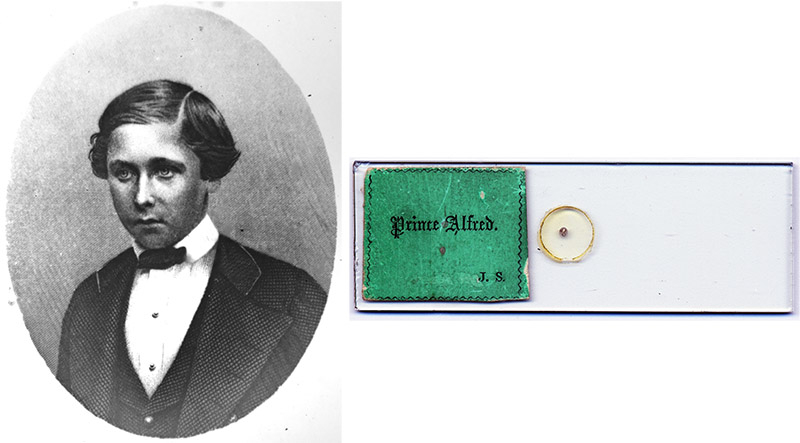

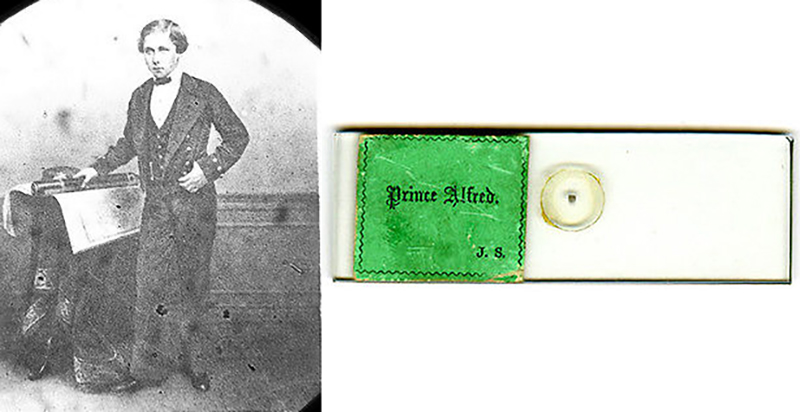

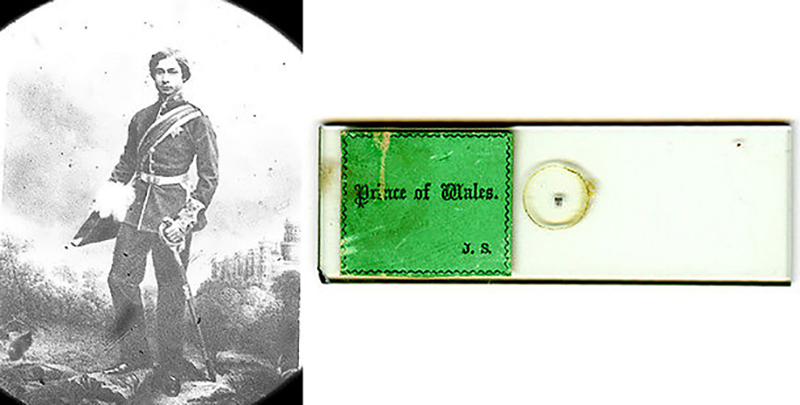

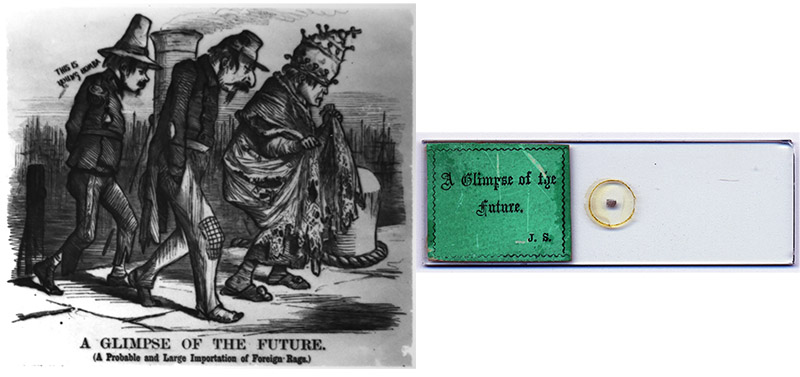

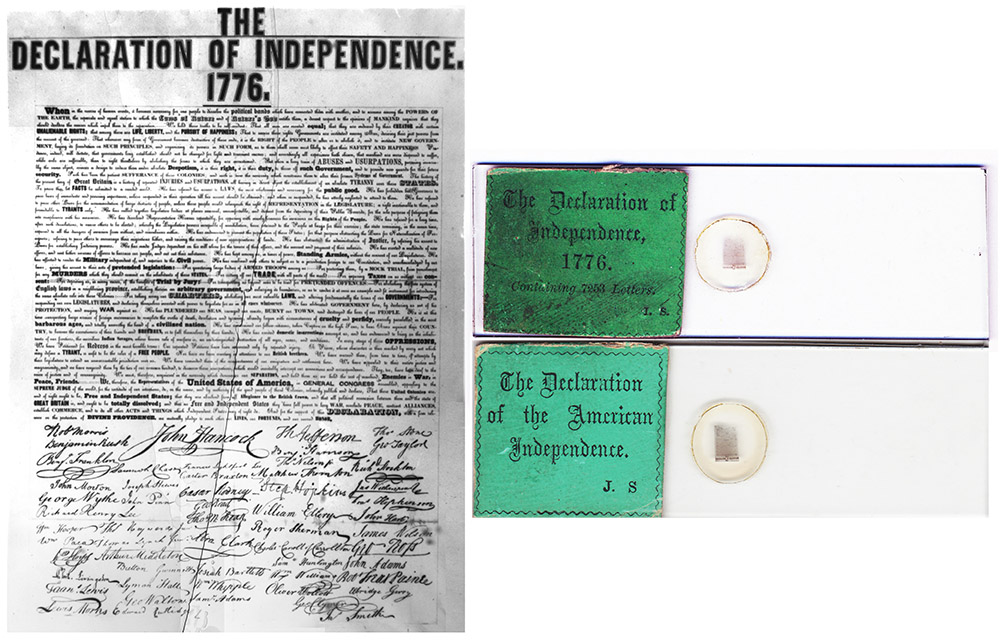

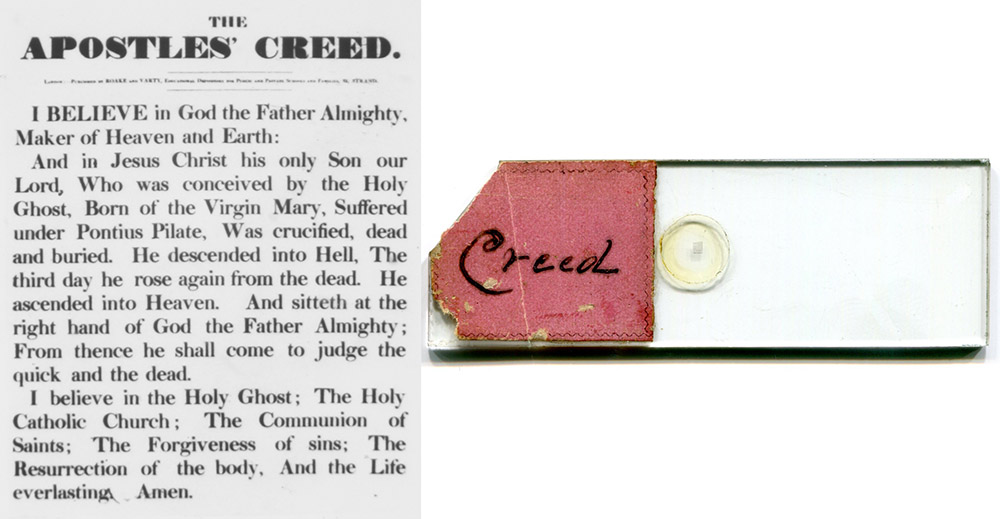

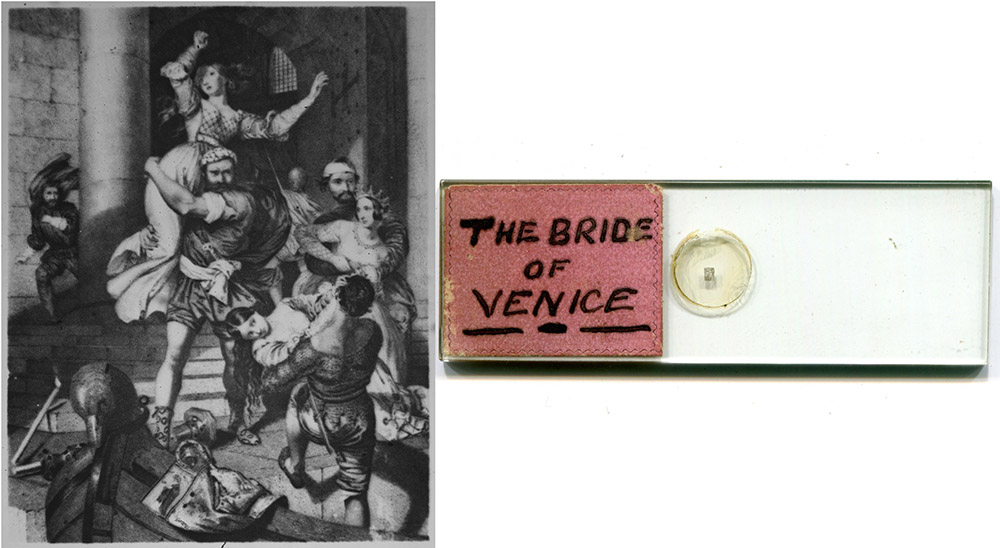

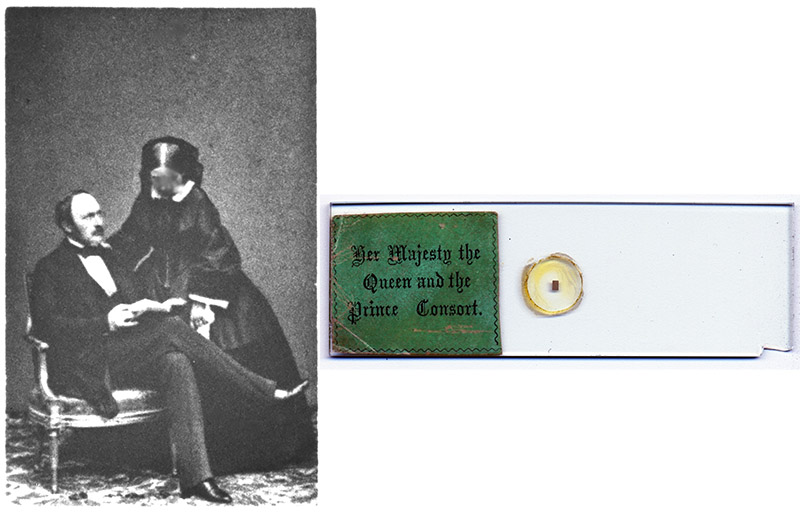

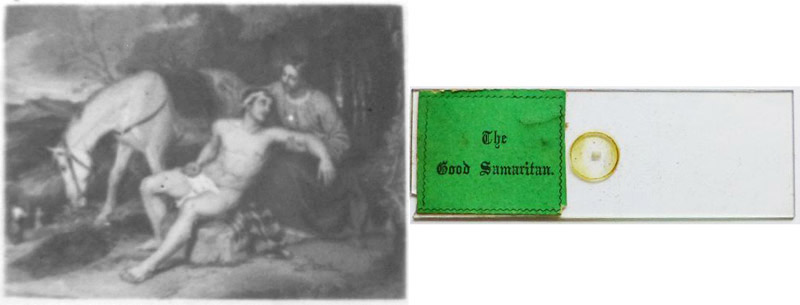

Victorian-era microphotograph slides are occasionally encountered that bear the initials “J.S.”, with descriptions of the photographs printed in a gothic font (“J.S.-gothic”) (Figures 1 and 2). These are distinctly different from the microphotograph slides of John C. Stovin, whose labels sometimes contain his initials as “J.S.” (for comparison, please see the illustrated essay about J.C. Stovin on this site).

A slide by “J.S.-gothic” has come to light that connects these slides to Joseph Solomon (Figure 1), a London supplier of photographic and other optical equipment and sundries.

Joseph Israel Solomon left behind two autobiographical documents: an 1887 essay of “Reflections of early days in photography”, and “Records”, apparently written just before his death. The whole of Solomon’s “Reflections…”, is included toward the end of this essay. Solomon used the name “Joseph Solomon” or “Joseph Israel Solomon” during his dealings in England, but appears to have gone by “Israel Solomon” after moving to the USA. Numerous documents indicate that these were all names of the same man.

The 1835 London register of voters lists Joseph Solomon as living at 22 Red Lion Square, in the Finsbury/Holborn area. The 1851 census recorded Solomon at that same address, working as an “agent for the sale of French Manufacturers”. He evidently spent much of the intervening time in Paris, following his cousin’s advice. His wife, Caroline, was Parisian, as were also their two children. Daughter Isabelle (“Bella”) was born in Paris ca. 1840, and son Isaac was born there ca. 1846. From these records, and the retention of the Red Lion Square address, it appears that Joseph moved back-and-forth between London and Paris.

While living in Paris, in 1840, Solomon began dabbling in photography. He wrote in “Recollections”, “About the year 1840, I purchased, in company with my brother-in-law, a portrait artist and a painter of landscapes, a set of daguerreotype apparatus from a well-known large artists' color store then in the Rue Coque St. Honored which street does no longer exist in Paris. We set out to follow, as near as possible, the written published methods to obtain a picture, but failed. I remember that to obtain the vapor of iodine on the silver plate, either before the mercury was on it or after, I placed the iodine in a small dish in the corner of a room and held the plate over it for a very tiresome time and obtained nothing but smudges instead of pictures, and I abandoned the whole thing”.

Solomon then gives some examples of his cross-Channel trade, with London manufacturer and retailer Edward Palmer (1803-1872). Of note, Palmer was master to W.H. Thornthwaite, who later bought Palmer’s business and established the optical and scientific company of Horne and Thornthwaite. Palmer sold his business in 1845 or ’46, thereby giving a date range to Solomon’s anecdotes, “I was an inhabitant of Paris for some years and then went to London to obtain orders for French manufactured articles, particularly opera glasses, and represented the manufacturer of superior opera-glasses in Paris. Palmer, a druggist, who also kept a furniture store and articles of science in Newgate Street, London, gave me orders for various articles, amongst which was a quarter portrait lens… Amongst the sundries was a bottle containing six or eight pounds of the new chemical, hyposulphite of soda. I found the manufacturer and purchased four kilos, a little over eight pounds English. I did not know the exact price, but Palmer's people had given me the liberty to pay whatever the French chemist charged. They would pay, if even beyond the English manufacturer's price in England, so I quite fulfilled their order on all they wished me to purchase for them, and I left France for England about three months after. When I arrived in London I paid duty on what I brought with me, and charged Palmer eight shillings per pound for the hypo. They then made a grand fuss and reduced their retail price to what the wholesale manufacturers were charging for it wholesale. Then the article began to find its use in the manufacture of paper, and Newcastle-on-Tyne manufacturers made it in tons, so that it was sold retail for ten shillings per barrel of 100 pounds weight”.

Opera glasses from France were a major part of Solomon’s business, in addition to photographic apparatus and supplies. Of these various optical devices, Solomon wrote, “The glass used in making the lenses was partly of flint and partly of crown, and the method of obtaining the specific gravity of glasses was at that time unknown to the ordinary working optician. Would it be out of place to cite an accident which occurred to a manufacturer of object lenses for opera glasses in Paris about this time: He was very neat and particular in his grinding and always turned out the best quality of opera glasses. I employed him to make for me, as a venture, one dozen quarter portrait lenses, double combination, which he thought he could do, as he happened at that time to have a stock of both crown and flint glasses perfectly adapted for this purpose. He soon made twelve of these instruments, that could not be surpassed for quickness and sharp definition. I sold them without trouble and thereafter continued to give my increasing orders. The price I placed upon these lenses was twenty shillings each, and Andrew Ross, hearing from others of this extraordinarily cheap and good lens, obtained one from me and was quite surprised to find that the lens was all that was claimed for it. I had sold up to this time about 100 of these lenses and was continuing to give my orders for them in large quantities. A batch soon arrived from Paris, however, and was tested (as every lot of lenses was before being placed upon the market), and to my surprise was found to be greatly inferior in quality to those which I had previous had from this glass grinder. I wrote to my friend and found that a great accident had happened in his shop. He kept his glasses in the cupboard; one containing all of the discs for my quarter lenses, and the other the lenses for his opera glasses. An apprentice, who had been ordered to dust each cupboard, had gone beyond his order and taken the lenses from the two clipboards, and in the confusion of dusting had mixed them so that when the workmen, who were ignorant of the quality of glasses, attempted to make the combination they used the discs recklessly, just as they happened to come, without regard to their specific gravity or other differences. The result was that I could obtain no more correctly made lenses until he had obtained from a scientific optician the specific gravity of the mixed lenses and had them placed in their proper cupboards again”.

Solomon exhibited������������������������������� at the London Exposition in 1851. His entry in Class 10, “Philosophical, Musical, Horological, and Surgical Instruments” was listed in������������������������������ the official catalogue as “Solomon, J. 22 Red Lion Sq. Manu. – Registered papier-mâché opera glasses, eye protectors, etc.”. While he was recorded as being the manufacturer, his items were almost certainly French imports.

Although he was well-acquainted with the uses of the items he sold, Solomon admitted to being u��naware of the physics of optics. He wrote, “Scientific opticians were not numerous at that time, and when, in 1851, the great Universal Exhibition was held in London, I introduced Monsieur Buron, of, Paris, to Andrew Ross; but Monsieur Buron could not speak English, nor could Ross, French. I, of course, acted as interpreter, but was rather a poor one, I imagine, for shortly Monsieur Buron took a pencil and presented to Ross a paper with some geometrical curves and lines with explanatory algebraic letters inscribed thereon which Ross seemed to understand and answered by another with similar curves and lines. Both seemed pleased; but I do not know to this day what those hieroglyphic marks indicated to those two men”.

On March 28, 1860, Solomon was elected to membership in the Society of Arts.

For unknown reasons, Joseph Solomon filed for bankruptcy in 1878 (Figure 7). Yet, in 1881, he was living at 22 Red Lion Square, listed on that year’s census as a “dealer in photographic materials”. The bankruptcy may, therefore, have been part of a financial rearrangement for his business.

In June, 1881, Joseph Solomon left England for New York, and remained there until his death, in 1890.

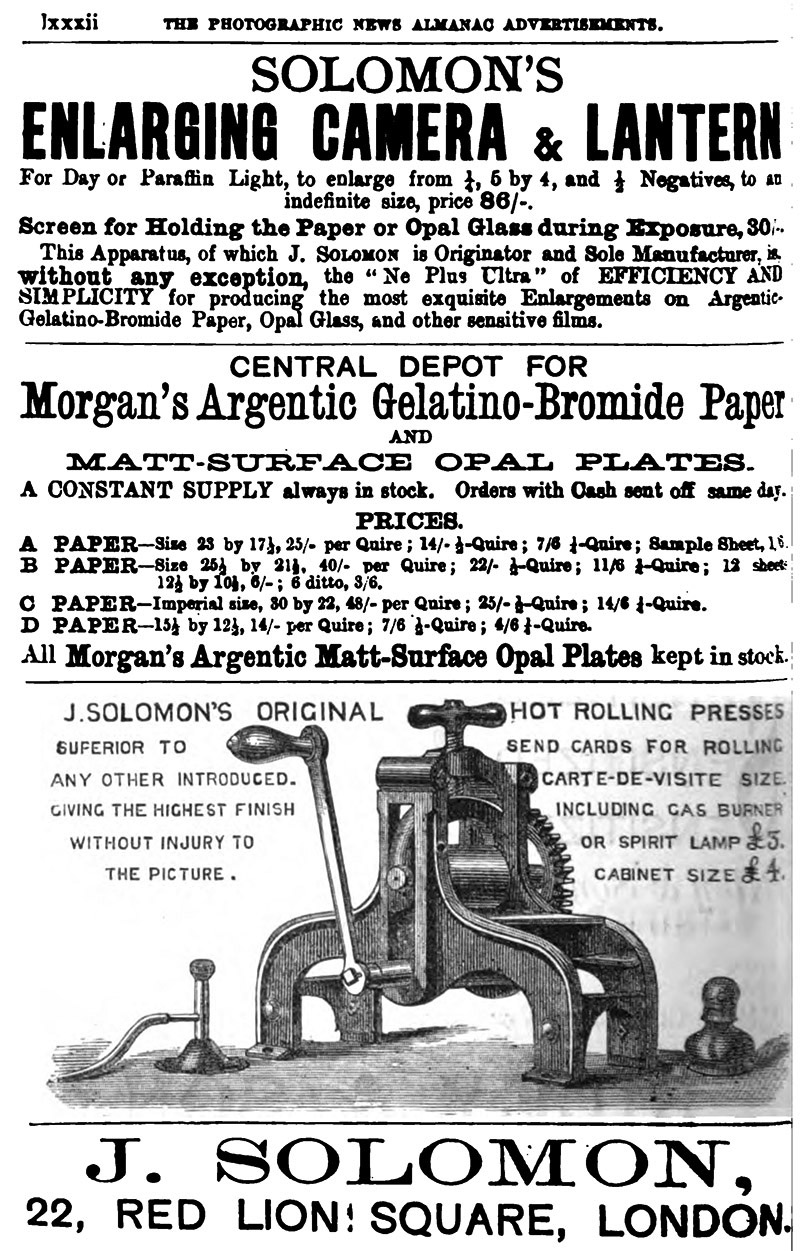

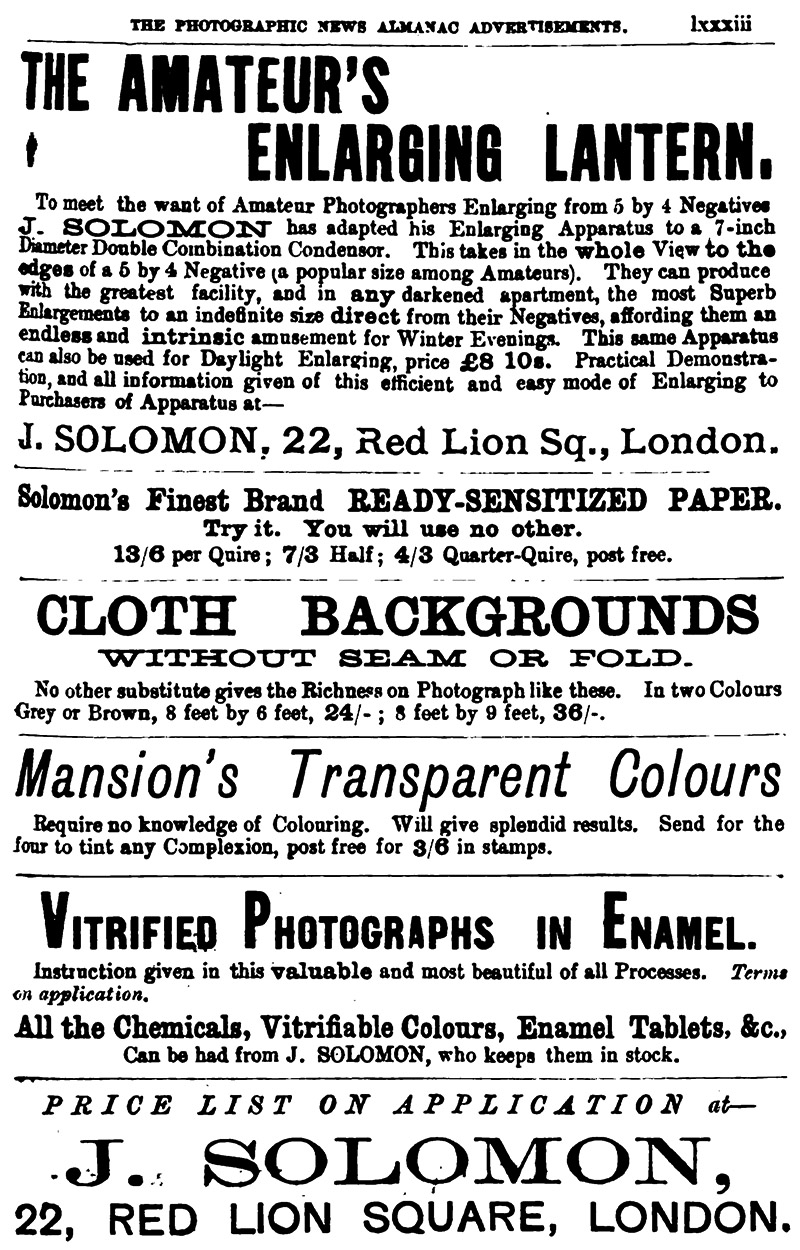

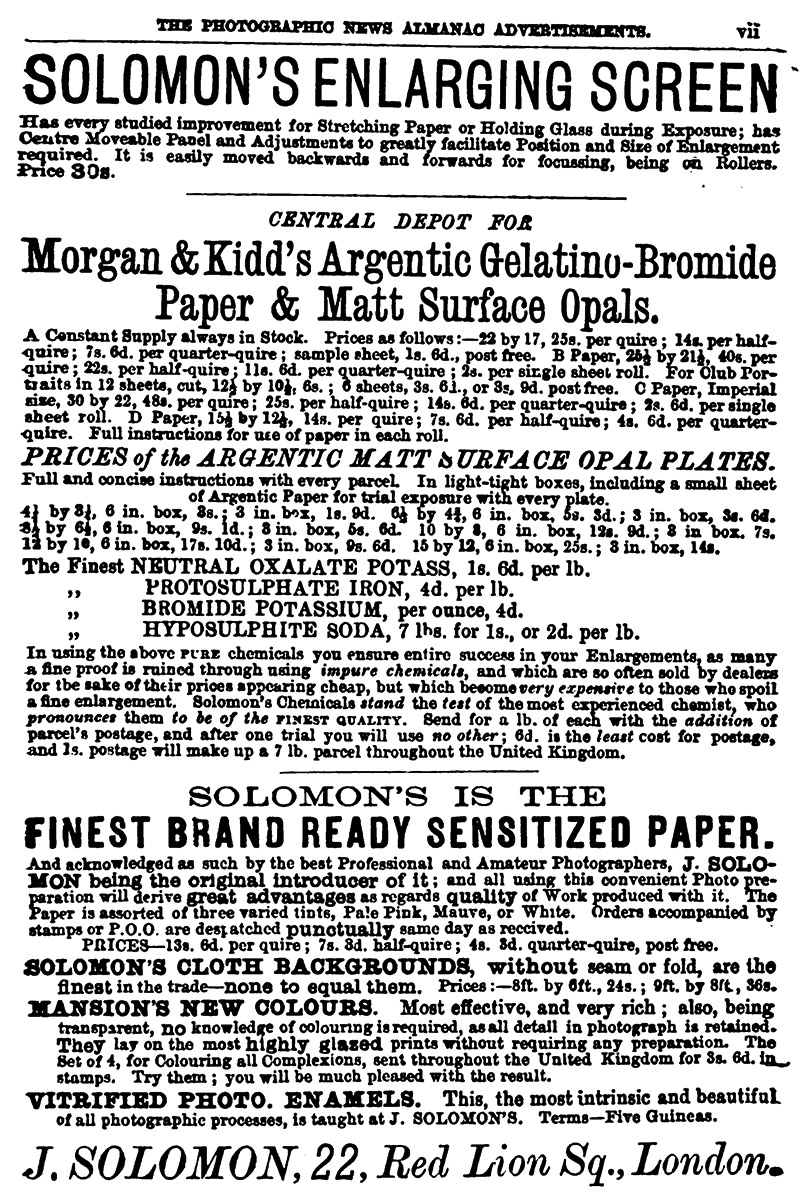

Confusingly, Solomon’s business in London was still going strong in 1884 and 1885 (Figure 8). He may have retained ownership and managed from across the Atlantic, or it may have been owned and operated by someone else who retained the business name. A possibility is son-in-law Henry, who worked for Joseph at the time of the 1881 census. I have not found any records of Solomon’s London business from after 1885.

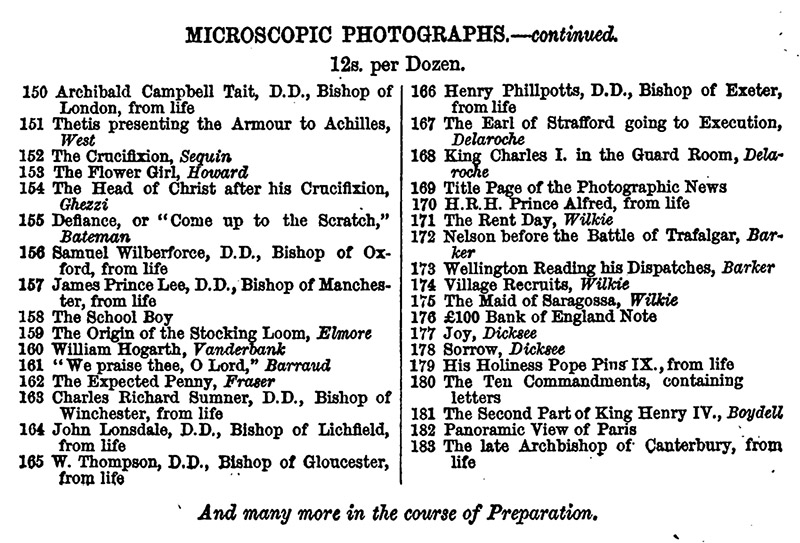

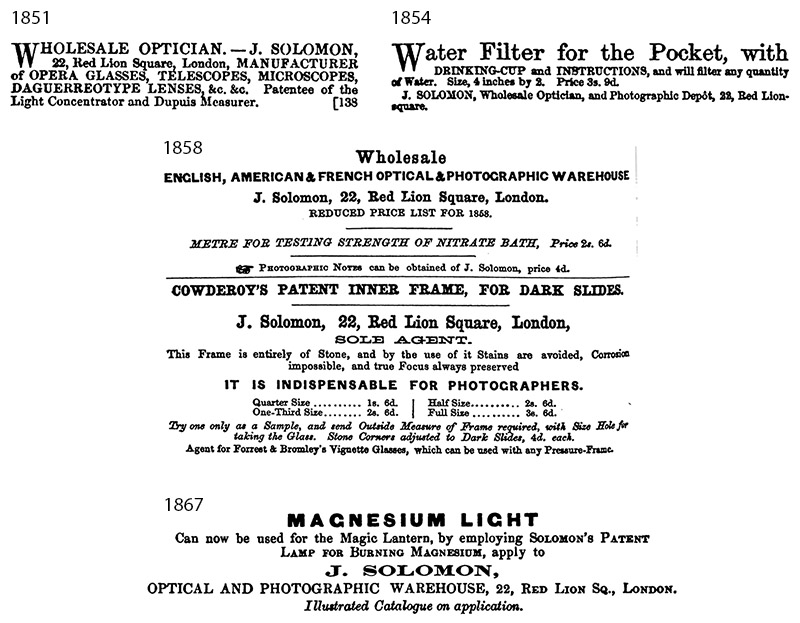

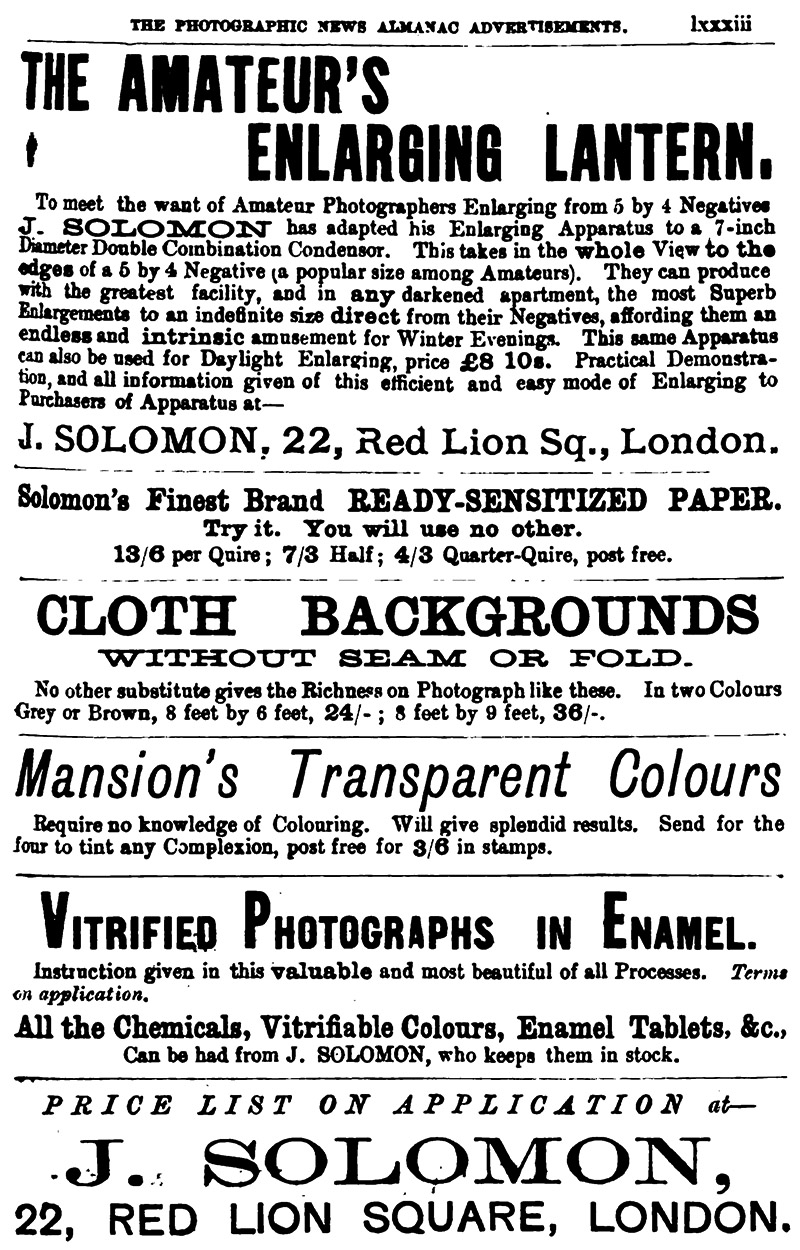

Figure 5.

Some advertisements from Joseph Solomon: 1851, ‘Official Catalogue of the Great Exhibition’; 1854, ‘The Lancet’; 1858, ‘Photographic Notes’; 1867, ‘Quarterly Journal of Science’.

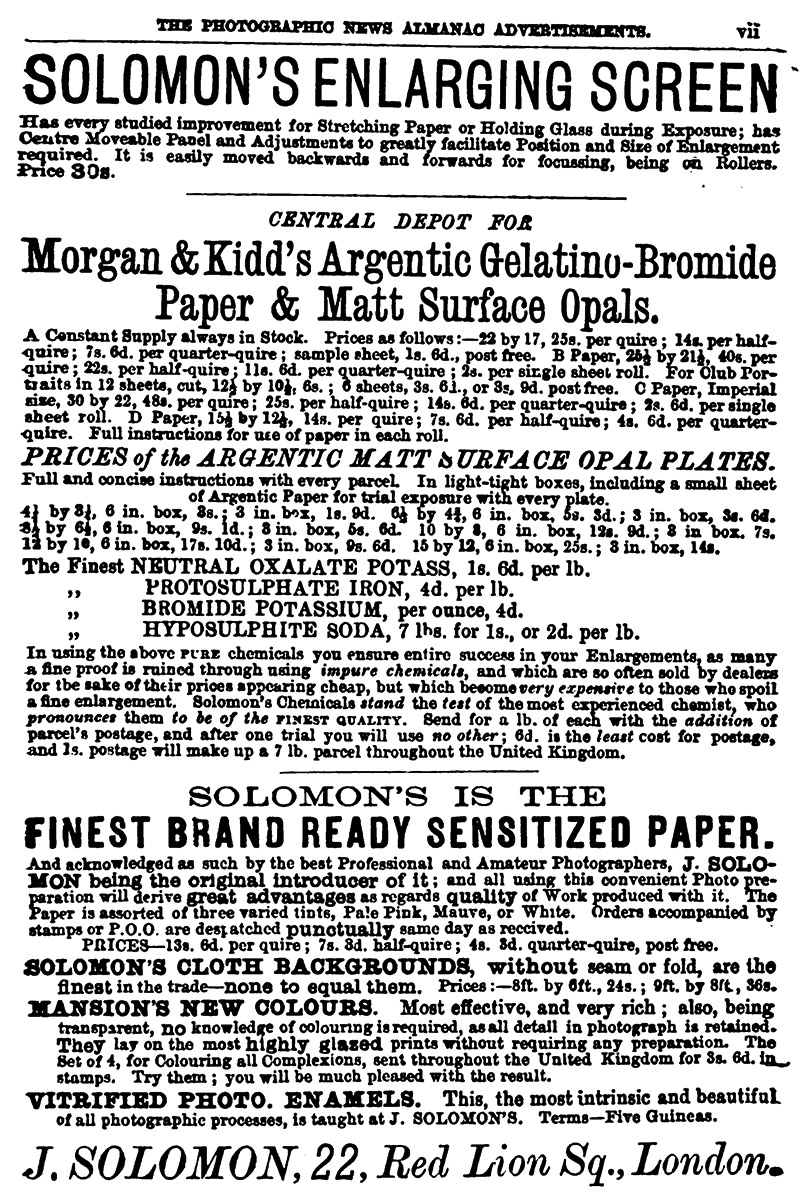

Figure 6.

A J. Solomon magnesium light. He wrote in ‘Recollections’, “About the year 1865, the discovery was made that magnesium was not so rare as was hitherto supposed. It had formerly only been seen in the cabinets of scientific collectors of rare metals, etc., but now magnesium was sold by a firm in Manchester in the form of very small wires about seventy to eighty yards to an ounce, and this wire, when set fire, burned with a splendid white flame which was suitable for making photographs. I purchased with much difficulty one-quarter of an ounce for twenty-one shillings. I was much excited over this discovery, and thought from the light so near sunlight that it would greatly benefit the photographers of London, where so many dark days prevailed in the winter, and thought it would also help photographers to work at night. I thought it might also be used for the magic lantern, but the manufacturer of the metal could not produce it free from alloy with other matter. I had this light adapted to the machine for enlarging small pictures, which it did in many instances, before rock oil was better understood. For some years I made the sale of magnesium the specialty of the house with which I was connected, and I have no doubt I was the best customer of the manufacturer of that metal. I may mention that one customer of mine, a Mr. Parker, an antiquarian, and photographer of grottos and dark places, kept in his employ a photographer especially to make photographs by the aid of magnesium”. Images adapted for educational, nonprofit use from http://diaprojection.unblog.fr/2014/05/29/les-lampes-au-magnesium-solomon-et-gillet-forest/comment-page-1/.

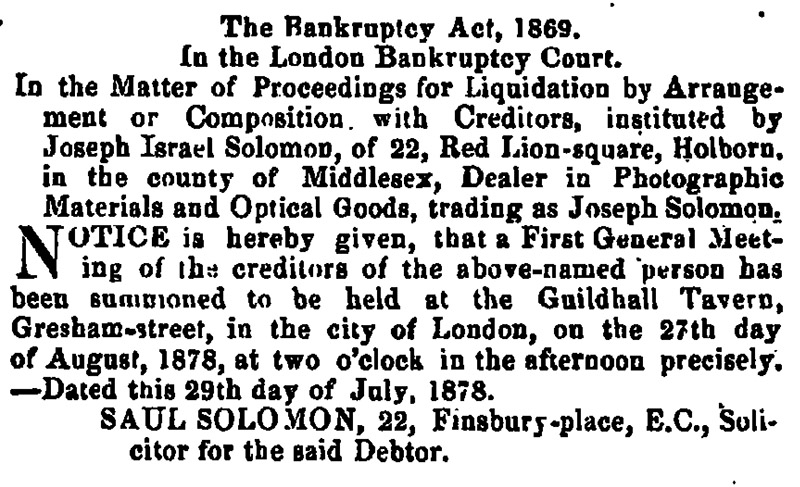

Figure 7.

1878 announcement of Joseph Solomon’s bankruptcy.

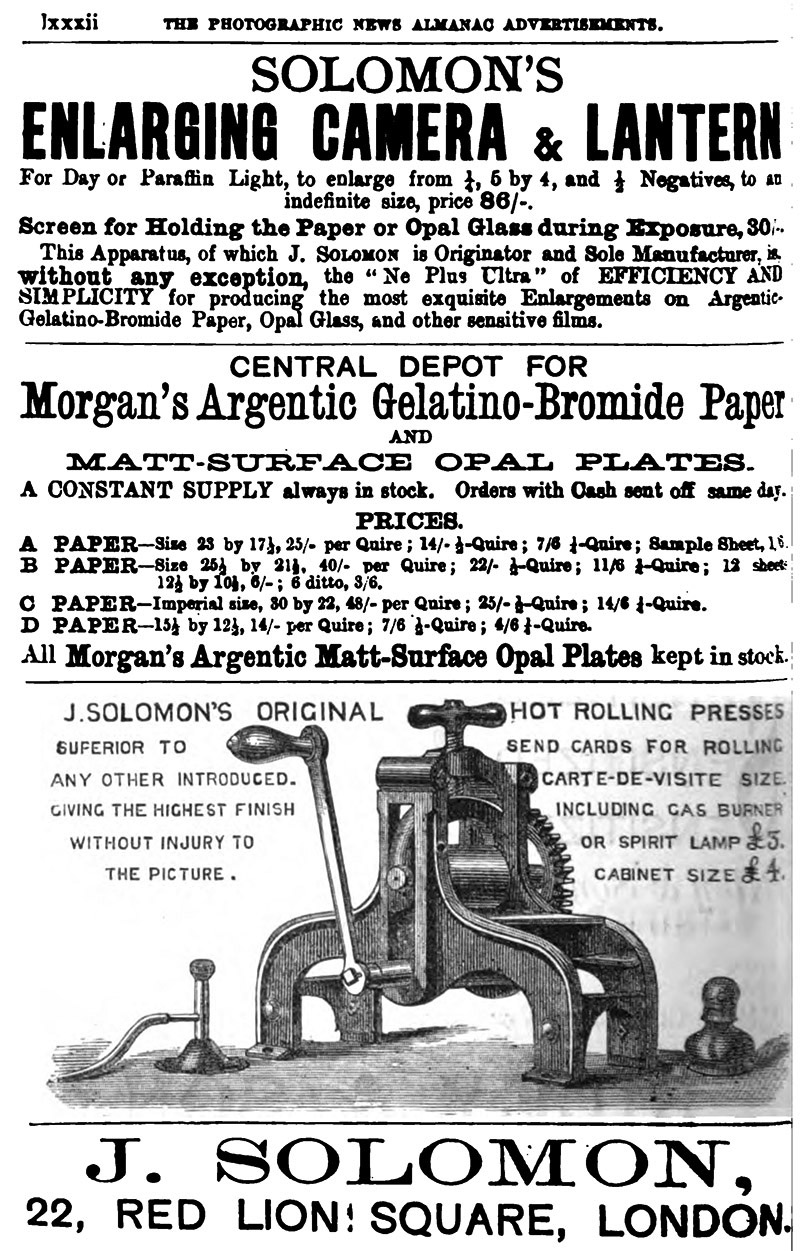

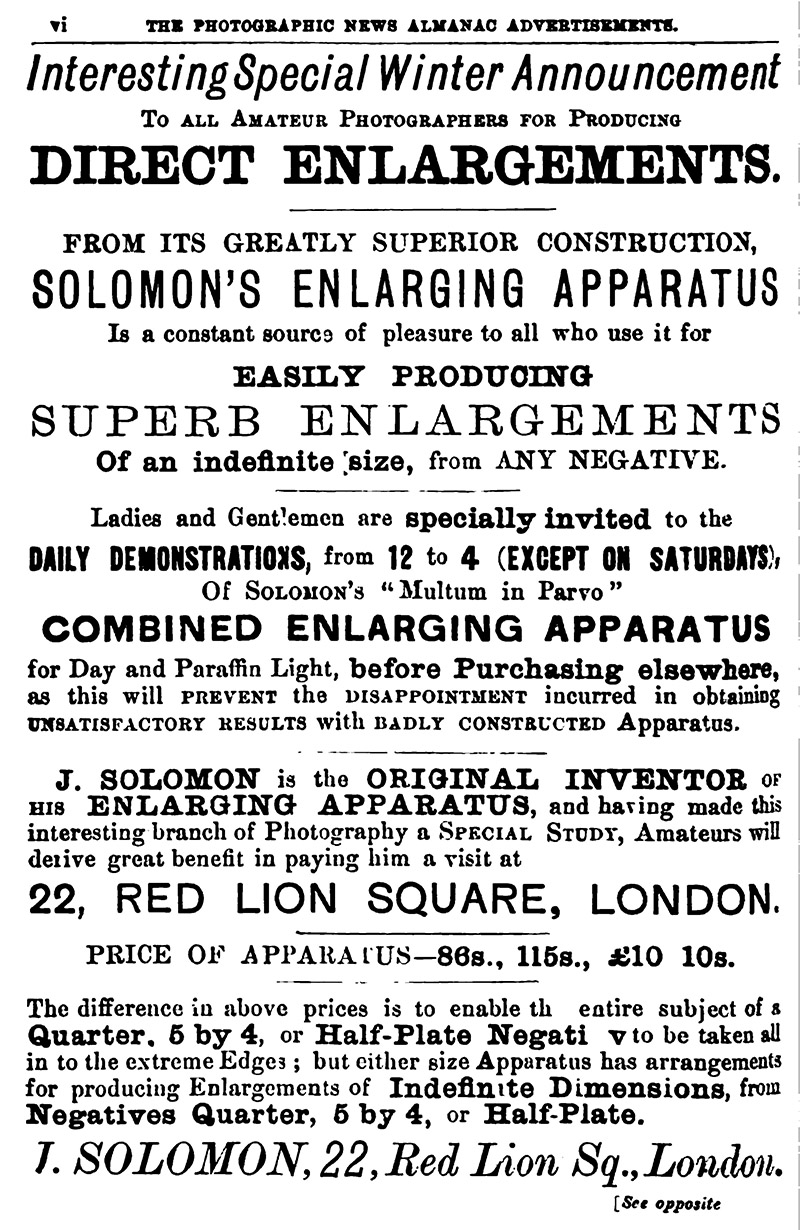

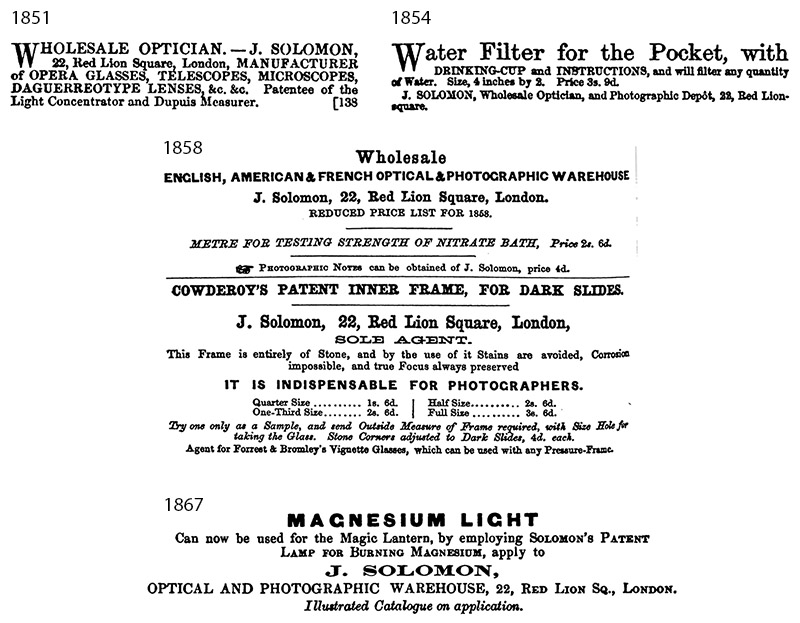

Figure 8.

Advertisements from ‘The Year-Book of Photography’, 1884 (top two) and 1885 (lower two). Joseph Solomon moved to the USA in 1881, and it is not known who operated the business at 22 Red Lion Square during 1884-85.

From The Photographic Times and American Photographer, 1887, published in 6 parts. Obvious typographical errors have been fixed.

Recollections of Early Days in Photography

By J. Solomon, Late of Red Lion Square, London, England.

Introduction

The discovery of fixing shadows is another advance in scientific knowledge obtained by men of the nineteenth century. It had been seen even as early as in the days of the Ptolemaies, that if a hole or small crevice occurred in the wall facing a landscape or sea-shore, when the closet was closed and dark, the light penetrated the hole or crack, and the shadow from without was reflected upside down on the wall opposite to the opening in the wall. Alchymists had observed that these shadows were darkened by light on silver. The power of steam was observed, and a small toy was made, in those ancient days, showing its power. The magnetic attraction of amber was observed, and it was called electron, from which was formed the term electricity.

Yet from these ancient dates to the seventeenth century, no advance or application of these powerful forces in nature for the use of mankind were put into effect. Now the dark clouds which obscured the light of freedom from the middle ages are passing away, and we are nearing the threshold of great results for the general welfare of mankind.

In the summer of 1839, all Paris was excited on hearing that one of the greatest discoveries ever made by man was made by a Frenchman. Monsieur Arago, the great astronomer, informed his fellow academicians that the report was a fact, having been made certain by being admitted into the secret by the discoverer, a Monsieur Daguerre, the well-known artist in scene, dioramic and panoramic pictures. The great discovery was, that the sun's shadows, as they were seen on the screen of a camera obscura, could be fixed on a surface and handled the same as a picture made by hand in the ordinary way.

Another member of the Academy recommended that, for the honor of France, the secret should be purchased by the government and given to the world. The king, Louis Philip, supported the proposition, and Monsieur Daguerre was made an officer of the Legion of Honor, and well paid for his discovery.

Either about the same time, or shortly after the negotiation for the purchase of his secret, he went to England, and from the aid given him, in London, by a Frenchman named Claudet, was enabled to obtain an English patent.

The English patent was placed in the hands of an agent to sell, and, although the French Government purchased the secret to give to the world, the English patent debarred the gift to the English nation. The government discovered that others were in the field besides Monsieur Daguerre, searching to fix the shadows as seen through a camera obscura, and the government, I believe, gave a pension to a Mr. Niepce for his researches, and, afterwards, to a nephew of Mr. Niepce, who was in the army, but, in his leisure, pursuing the researches of his uncle. He was granted a suite of rooms in the Palace of the Luxembourg, to continue his researches on fixing the colors in the shadows.

I have seen �������������������������������������������������������one of these pictures, which was a large bird, with brilliant, various colored feathers. The picture was on silver plate, about whole siz�����������������e (6 ½ x 8 1/2 inches), and the colors, although true, were not pleasing, from having a Dutch metal, dazzling effect; and the picture was only to be seen in a darkened room, by the light of a small candle. It was rumored that Daguerre had made with Niepce a tacit agreement, that each should inform the other of any progress or discovery, and that they should share in the success, if the object sought to be obtained was gained; but that Daguerre, who had received many hints from Niepce's studies, had not informed Niepce of his discovery. No doubt this rumor was a libel on Daguerre.

After Daguerre obtained his patent in England, he gave a written authority to Mr. Claudet to take pictures in London, without requiring any permission from the purchaser of the patent, and when portraiture was obtained on silvered plates, the purchaser of the patent, Henry Beard, a coal merchant, opened a studio in the Polytechnic Exhibition Building, at the top end of Regent Street; and Mr. Claudet opened a studio in the corner building, at the bottom of Regent Street.

Beard gained more than £100,000 from his purchase of the patent, and at the same time Niepce and Daguerre were pursuing their researches to obtain the colored shadows as seen in the camera obscura. Others, in different countries, were searching to obtain the means of fixing them, and amongst them was a Mr. Talbot, a descendant of an English noble family. He was a member of the Royal Society, and discovered the means of fixing the shadows on paper, and he was probably the first who obtained copies printed from the first picture taken. Mr. Talbot also patented his discovery, and the honorable position of Mr. Talbot as member of the Royal Society caused many sneers and reproaches towards him, and the public considered that he should have freely given to the English people, as he was rich in means and high in descent.

About the year 1840, I purchased, in company with my brother-in-law, a portrait artist and a painter of landscapes, a set of daguerreotype apparatus from a well-known large artists' color store then in the Rue Coque St. Honored which street does no longer exist in Paris. We set out to follow, as near as possible, the written published methods to obtain a picture, but failed. I remember that to obtain the vapor of iodine on the silver plate, either before the mercury was on it or after, I placed the iodine in a small dish in the corner of a room and held the plate over it for a very tiresome time and obtained nothing but smudges instead of pictures, and I abandoned the whole thing. The two first pictures shown to the general public was from the store of Susse Freres, the noted artistic store in the Place de la Bourse, and these two were pictures of the same object, a row of houses; and I think the pictures were on plates about 7x4 or 5. The pictures were taken from the same spot, and every brick, stone, crack, etc., appearing so microscopically exact, the lookerson were filled with astonishment. Prophets foretold that artists for landscape pictures were no longer required; but Daguerre expressed his opinion that it would never be useful for portraiture on account of the time required, fifteen or more minutes, to obtain a picture. The lens employed was a simple achromatic meniscus; but some time afterwards, Buron, the largest optical manufacturer in Paris, produced the double combination lens for obtaining quicker results. From that time attempts for obtaining portraiture began.

I was an inhabitant of Paris for some years and then went to London to obtain orders for French manufactured articles, particularly opera glasses, and represented the manufacturer of superior opera-glasses in Paris. Palmer, a druggist, who also kept a furniture store and articles of science in Newgate Street, London, gave me orders for various articles, amongst which was a quarter portrait lens, and I remember the consternation I had. One of the assistants in unscrewing and rescrewing had changed the lenses, but the next day the error was discovered.

Amongst the sundries was a bottle containing six or eight pounds of the new chemical, hyposulphite of soda. I found the manufacturer and purchased four kilos, a little over eight pounds English. I did not know the exact price, but Palmer's people had given me the liberty to pay whatever the French chemist charged. They would pay, if even beyond the English manufacturer's price in England, so I quite fulfilled their order on all they wished me to purchase for them, and I left France for England about three months after. When I arrived in London I paid duty on what I brought with me, and charged Palmer eight shillings per pound for the hypo. They then made a grand fuss and reduced their retail price to what the wholesale manufacturers were charging for it wholesale. Then the article began to find its use in the manufacture of paper, and Newcastle-on-Tyne manufacturers made it in tons, so that it was sold retail for ten shillings per barrel of 100 pounds weight.

The making of daguerreotype portraits was an extensive occupation for many, and Henry Beard having speculated away all his immense gains, had no means of renewing the patent's last payment of £100, so it fell into the public hands, and thousands of people commenced taking daguerreotype pictures. The requirements in materials was very varied, and some very expensive, such as deep glass dishes, two of which was in one box, shut out from all light, and on the top of the dish the portrait was placed to receive the iodine and the other fumes. Small doors at the side with looking glass were opened to obtain a glimpse from the top of what was going on. The daguerreotype plate in England was manufactured by a company called the Soho Plate Company, Birmingham, and in Paris a firm commenced to manufacture the plate and erected steam and rolling mills. The name of the firm was Alexis, Gaudin & Co., and they also commenced manufacturing every requisite required in the art, and the duty in England was twenty-five per cent., and other expenses of transit, etc., nearly ten per cent, extra, yet the French house could pay the duty and expenses and quite undersell the English manufacturers.

On my journeys between France and England, the noted optician, Andrew Ross, and his son, used to request me to bring them specimens of the then advanced position of photography on paper, and for a picture on paper about the size of the album portrait I obtained from Andrew Ross ten shillings, being very careful only to fulfill such orders for houses of eminence, because Talbot pursued by law any one infringing his patent. Amongst other photographers in Paris, an artistic designer, for lithographic printing prepared a gelatine negative on glass, and one order from Willet, an optician, was to purchase a prepared gelatine glass to cost ten francs, but, of course, not being properly preserved from light, it was useless for obtaining a portrait.

The photographic studios very soon became numerous and caused a great stir among the trades that attempted to supply the increasing demands for frames, etc., and among the manufacturing opticians who undertook to produce lenses that would make sharp pictures and reduce the time of exposure. These difficulties were not overcome so long as the daguerreotype held its sway. The glass used in making the lenses was partly of flint and partly of crown, and the method of obtaining the specific gravity of glasses was at that time unknown to the ordinary working optician.

Would it be out of place to cite an accident which occurred to a manufacturer of object lenses for opera glasses in Paris about this time: He was very neat and particular in his grinding and always turned out the best quality of opera glasses. I employed him to make for me, as a venture, one dozen quarter portrait lenses, double combination, which he thought he could do, as he happened at that time to have a stock of both crown and flint glasses perfectly adapted for this purpose.

He soon made twelve of these instruments, that could not be surpassed for quickness and sharp definition. I sold them without trouble and thereafter continued to give my increasing orders. The price I placed upon these lenses was twenty shillings each, and Andrew Ross, hearing from others of this extraordinarily cheap and good lens, obtained one from me and was quite surprised to find that the lens was all that was claimed for it. I had sold up to this time about 100 of these lenses and was continuing to give my orders for them in large quantities. A batch soon arrived from Paris, however, and was tested (as every lot of lenses was before being placed upon the market), and to my surprise was found to be greatly inferior in quality to those which I had previous had from this glass grinder. I wrote to my friend and found that a great accident had happened in his shop. He kept his glasses in the cupboard; one containing all of the discs for my quarter lenses, and the other the lenses for his opera glasses. An apprentice, who had been ordered to dust each cupboard, had gone beyond his order and taken the lenses from the two clipboards, and in the confusion of dusting had mixed them so that when the workmen, who were ignorant of the quality of glasses, attempted to make the combination they used the discs recklessly, just as they happened to come, without regard to their specific gravity or other differences. The result was that I could obtain no more correctly made lenses until he had obtained from a scientific optician the specific gravity of the mixed lenses and had them placed in their proper cupboards again.

Scientific opticians were not numerous at that time, and when, in 1851, the great Universal Exhibition was held in London, I introduced Monsieur Buron, of, Paris, to Andrew Ross; but Monsieur Buron could not speak English, nor could Ross, French. I, of course, acted as interpreter, but was rather a poor one, I imagine, for shortly Monsieur Buron took a pencil and presented to Ross a paper with some geometrical curves and lines with explanatory algebraic letters inscribed thereon which Ross seemed to understand and answered by another with similar curves and lines. Both seemed pleased; but I do not know to this day what those hieroglyphic marks indicated to those two men.

Some three months after the great Exhibition of 1851 was opened, my old acquaintance, a lithographic artist of Paris, sent to the Exhibition about four photographs on paper, printed from glass negatives of about 8 1/2 by 6 1/2 inches in dimensions. These were the only paper negatives in the entire Exhibition, and public curiosity was naturally aroused at their appearance.

Public curiosity was again excited by the first stereoscopic pictures taken from natural objects by the clever Parisian optician, Dubosc. Sir Charles Wheatstone, the inventor of the stereoscope, which in form resembled the graphiscope, was a customer of mine some years before he died. He came to my house a few weeks before he went to France and complained to me that his invention of the stereoscope had not been done justice to by the firm to whom he had entrusted the model. He said he had also invented something nearly allied to the stereoscope, but which showed a most pleasing and amusing optical illusion. When he returned from France he said he would reveal the secret to me and bring it before the public; but, unfortunately, he never came back to England.

Dubosc invented the general form of the stereoscope as now used, but he did not benefit himself by the invention. Dubosc was the first to show that small-sized photographs could be enlarged, and I was shown by him the first enlarged photograph which he had made from a small glass image - the light used coming from an electric lamp of his own invention. The exhibition closed to the public, and only purchasers of goods from the exhibition when it was opened, and the owners and packers of goods, admitted. Dubosc, the optician, in Paris sent to an agent in the palace stereoscopic pictures taken from natural objects on daguerreotype plates. I was the first to whom the pictures and stereoscopes were shown, and I agreed to take all that he received at six francs each and also pay for the stereoscopes. The agent tacitly agreed to sell all to me. Prince Albert visited the exhibition daily and the agent showed him the pictures. The agent did not keep his agreement with me, but sold the pictures and stereoscopes to the prince and queen.

But I soon found a very clever daguerreotype artist named Laroche, of Oxford, London, for whom I purchased statues and other plaster of Paris objects, which he reproduced for me in stereoscopic slides. He soon became very clever in stereoscopic portraiture, and I have now two colored portraits quite free from any fading and very artistic, which were made by him at that time by the stereoscopic process.

Laroche became quite prominent in daguerreotype portraiture, and his ambition urged him to produce portraits by photography on paper. Talbot opposed his productions because they infringed his patent, and a meeting was called to aid Laroche in his opposition of Talbot; but the final verdict was in favor of Talbot. The public, however, was so strongly opposed to Talbot that he was obliged to yield to its opinion and soon gave up all his rights to the public.

At that period the lenses which were in highest favor were those made by Voightlander, although these lenses never gave correct images because the chemical and optical rays were not coincident. The eminent optician, Alex. Ross, soon used his knowledge to produce lenses perfect in this respect. Soon after a young German, Dallmeyer, entered the employ of Ross, ultimately marrying his daughter, and after the death of Alex. Ross, being taken in as partner of Thos. Ross, son of Andrew Ross. The two, however, soon quarreled, and a separation of the firm took place.

In 1848 another great discovery in photography excited public curiosity. Schoenberne had made a very explosive compound from the innocent article of cotton wool. It was claimed that warfare would be entirely changed through this invention, but then a man named Maynard, of Boston, dissolved the gun cotton with ether and spirits of wine into a liquid jelly, and when dry the particles were found to be very valuable for surgical use in covering wounds. Mons. La Gray, of Paris, a rising and clever photographer, gave it as his public opinion that this substance could be made serviceable for photographic purposes.

In the month of February, 1851, F.S. Archer, of London, first published in the Photographic News that he had sensitized collodion, and had succeeded in pouring it upon glass on which he could make pictures. This new advance in photographic manipulation was at first very successful in attracting photographers, who then, as now, were very slow in adopting new methods, however improved or worthy of acceptation they might be. Soon, however, the tide began to flow in the direction of collodionized glass plates. At that time E. Drug and Wharton Simpson edited and published the Photographic News, and when the partnership dissolved, Simpson became the sole proprietor.

In the year 1853, on my return journey from Scotland, I stopped at New Castle on Tyne and called on Mawson, a druggist, who had commenced supplying photographers with requisite materials, and among other articles I showed him a student's microscope. A young chemist, at that time an assistant to Mawson, showed him, by the aid of this microscope, the structure of collodion. Thomas, a druggist of Pall Mall, London, was one of the first who followed Archer in the manufacture and sale of collodion, and it is generally reported that Prof. Pepper, a clever lecturer of the London Polytechnic Institute, gave the best method for producing a good-working collodion that immediately rose in reputation and realized for Thomas a large fortune. Mawson took into partnership his young chemist, and the firm became the largest manufacturers of collodion in the world.

The London University had a most excellent professor of chemistry, Rev. S.T. Hardwich, and a very ardent lover of photography. He published many excellent notes on any new discovery that aided in producing photographic pictures. In this he emulated the example of Hunt, of Cornwall, who was the founder, I believe, of the Falmouth Technical Institute, and who encouraged in every way the growth of photographic knowledge. Unfortunately for photography and science in general, he died at an early age.

I am not quite certain, but I believe that Sutton, editor of the Photographic News, followed Hardwich, the professor of chemistry, at the college for some short period, but in this I may be in error. Sutton was a personal friend of mine, and we passed many agreeable hours together. He was most virulent when writing in opposition to an assailant, but in conversation one of the most attractive men one could meet, and was ever ready to help any photographer out of a difficulty. He was the inventor of a large globe lens. Thos. Ross manufactured the lenses and cameras, and the pictures were good, but the dark slides were made to hold bent glasses. This difficulty stopped its success. Sutton lived in the Island of Jersey, from where he issued his journal, the Photographic News. I will now relate the difficulty which the changes in photographic manipulation occasioned daguerreotype artists in India and other colonies of Great Britain.

My friend, Frederick Yorke, the eminent artist photographer, lived at the Cape of Good Hope. He was by trade a chemist and druggist, and went to the Cape of Good Hope to become its chief daguerreotype artist, but when the change obliged him to adopt the collodion process, he obtained, with great difficulty, the necessary chemicals. In 1854 he was obliged to distil alcohol from a vile Dutch brandy sent to the Cape, which was so acid - being only used for medicinal purposes - that, when it was put in the collodion and iodized, it turned the color of the collodion to that of port wine. Iodide of ammonium he had to make also. All these difficulties placed in contrast to the present easy way by which photographers produce their pictures, emphasizes both conditions by the contrast. Another great difficulty in collodion pictures in the colonies was that no ship would accept collodion on account of its easy combustion, so that collodion was only accepted by certain ships which carried gunpowder. Some ships accepted collodion as deck cargo, and the most trifling accident occurring, the whole cargo was thrown overboard.

The daguerreotype died hard, and many who had got their livelihood from it struggled on, but gradually were reduced to poverty. One morning, a clever daguerreotyper photographer who came to purchase a few plates, complained of the fallingaway of customers, at the same time exclaiming that he was dying of starvation. I asked him why he did not adopt the collodion process, and he answered me that he had no means of purchasing the requisite glass slides, etc. I offered to teach him and gave him credit for all that was needed. He very gratefully accepted my offer, and in a few weeks paid me. About three months afterwards he received his clients in a flaming robe de chambre, and treated them as recipients of his favors; the rush for portraits on collodion glass having been so great and profitable to him.

People from all conditions of life at once styled themselves "photographic artists"; poor dwarfed cobblemen and trades people of all denominations left their pursuits to become artists in photography. They pitched their tents on houses, between chimnies even, and some often above the chimnies! Others converting their parlors or little court-yards into studios, and some descending into coalholes to manipulate there. These are things that I have seen, and during that rush I opened studios on every street of London and occupied myself only in riding from one to the other to supply their wants and to receive their cash.

Even had the people I employed robbed me of fifty per cent., in a very short time the profits resulting would have made me a millionaire. The range of prices from quarter to half-size pictures was so great that it seemed like a fabulous mine of gold opened up to hundreds; but few laid up their profits for the future. Men who followed fairs and were adepts in cutting profiles on black paper, became good judges of posing the sitters, and I have known some of these people to be prudent enough not to spend all they earned, but became purchasers of real estate and afterward developed into respectable artists.

Some died leaving wealth, but very few remained at their posts in the advance of science. Mr. Grubb made the finest lens for landscape photography, and thus assured the future success of the greatest discovery of the nineteenth century.

A Dr. Morris, of Birmingham, first introduced sensitized collodion glass plates, which obtained a short success. The printing on plain paper was helped on by albumenizing the paper. This paper for some time was made by the French manufacturers, and to their abundant supply of eggs they should have been the sole manufacturers of this article, but the Germans, who were obliged to purchase their paper in France, paid an import duty, succeeded in combating the Frenchmen, and took their position in supplying the photographic dealers throughout the world on equal, or even better terms.

After Dr. Morris produced sensitized collodion glass plates, Bolton, of Liverpool, succeeded in giving a better one, and others followed in the same way; but Col. Stuart Wortley, a clever amateur photographer, produced a sensitized collodion plate that was even better. My close business transactions, as agent for the sale of sensitized collodion glass plates, allowed me to observe that whatever merit may be due to Col. Stuart Wortley, the success of his plates was chiefly due to his wife, a lady descended from a noble family, who was a maid of honor to the queen, but who assumed the position of a workingman's wife, in order to aid her husband.

The process for producing Talbotypes required so much neatness in manipulation, that if the suggestion made by Monsieur LeGray and so ably perfected by Mr. Archer, to employ a sensitized collodion, had not been made, the Talbot process would only have gone side by side with the daguerreotype, and would have not entirely superceded it, as it did.

Talbot pictures were made on a wax sensitized paper. The first pictures of this class which were shown by Mr. Talbot were small - not larger than 4x6 inches. Waxing paper was accomplished as follows: Into a strong silver-plated tray sufficient white wax was put, that, when melted, would be a deep clear solution. Place the tray over a small charcoal fire and lay the paper on the wax. Great care was taken that there were no air bubbles left upon the paper, and a sheet was removed from the wax, and, while hot, held over it to allow all the surplus solution to drip off. When cool the paper was put away to be sensitized. That being accomplished, after it had become quite dry, it was placed in a dark slide, and pieces of twine were adjusted to keep the paper smooth and flat. All the operations that were accomplished after the paper was sensitized, were, of course, done in a room lighted with red or yellow glass.

When the paper was exposed correctly it was full of detail. I think it was developed with gallic acid and fixed with hyposulphite of soda. The pictures were always of a reddish-brown color, and were never a perfect brown or black until chloride of gold was used.

The cleverest preparer of wax-sensitized paper was a man named Sanford, who was also a clever photographer, and at one time the largest producer of albumenized paper. Although he was neither a gambler nor a drunkard, he was never able to become rich, as he should have done from the large profits which came to him from many sources. There must have been a leakage somewhere.

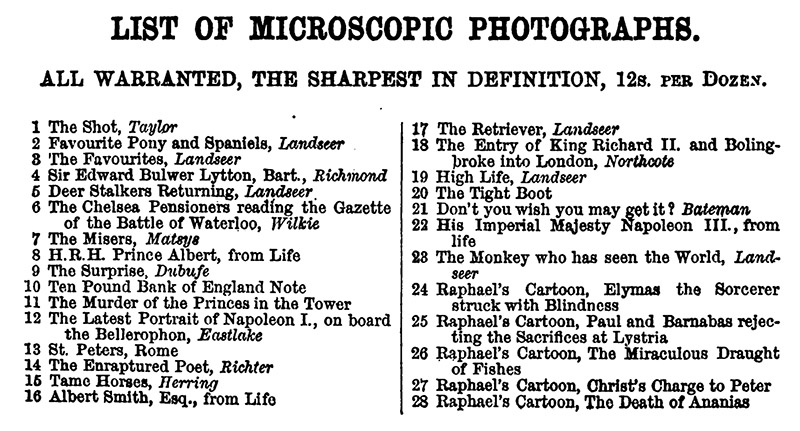

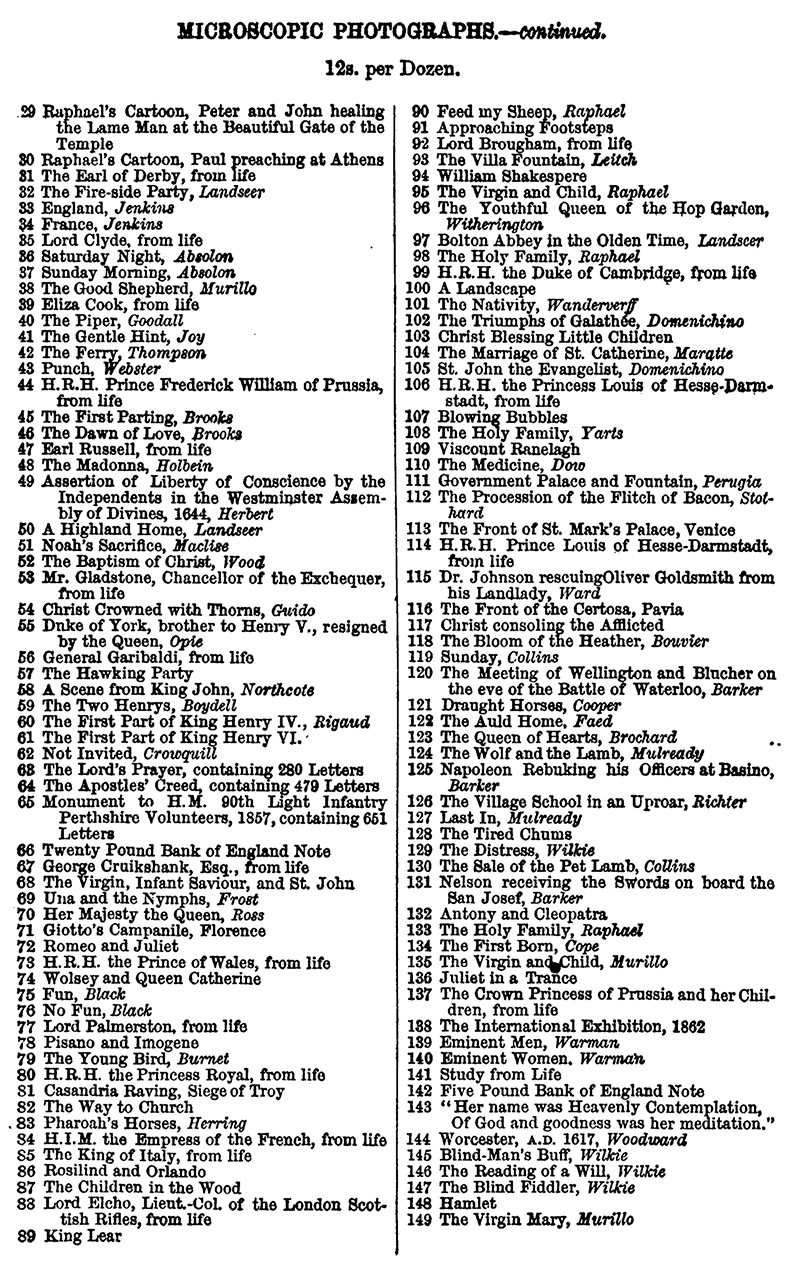

Among those who made immense fortunes in the great field of photography at this time were two that especially attracted attention; one, a descendant of a very humble family, died Lord Mayor of London; the other became a member of a successful firm of glass-blowers and dealers in barometers, thermometers, and other scientific instruments. These two men's sudden rise to fortune was related to me by Prof. Glazier, the eminent meteorologist, and president of the London Photographic Society. During the exhibition of 1851 the professor was sauntering about, looking at the scientific and other instruments in the show, when he picked up a small glass case, containing specimens of blownglass tubing for barometers, etc. He said to himself: "These were made by workmen whom I have long wished to find;" and he immediately sought the address - Negretti & Zambra, Hatton Garden, London. From the interview which followed orders were sent to them from the Greenwich Observatory, and extensive ones from the Government. When the great exhibition was closed, the building was purchased by a company, which made of it the great Crystal Palace, on their grounds at Norwood, near London. The trustees gave permission to erect a studio in the building, to manipulate in the production of photographic pictures. Permission was given to the undersecretary or principal bookkeeper of the Society of Arts, and, some years after, he granted the permit to Negretti & Zambra. Daguerreotype photography only had been carried on in the Palace up to this time, but soon after Talbot gave the right to use his patent by the public, and when Archer's collodion process was made known, the making of regular photographs in the Crystal Palace became immensely profitable to these fortunate men. They sold thousands of dozens of card stereoscopic pictures at 12 shillings per dozen.

There was another man who amassed a large fortune from the pursuit of photography. He early saw that photography would yield to anyone who followed it closely large profits, and he opened half of a shop near Hanover Square with the determination to make it pay. This man's name was Nottage. He placed over the door "Stereoscopic Co.," and exposed for sale stereoscopic and other photographic pictures. His success was due largely to the aid which clever photographic artists gave him at home and abroad. Among these we may mention the names of Wilson, of Glasgow; England, of London; and Ferrier, of Paris. Nottage took a large corner house in Cheap Side, London - erected on the top floor a studio for portraiture, and employed the best manipulators in photography. When the Exhibition of 1862 was opened, Nottage was purchasing largely from Mr. England, and he suggested to that photographer to offer a large sum of money to the managers of the Exhibition for sole permission to take photographs of the buildings and on the grounds, and also to erect a small building for the sale of photographs. He obtained the permission and he shared the speculation with Nottage. From the day it was opened until the last day the sales from photographs of the Exhibition amounted each day to £800, and at one time to £1,400.

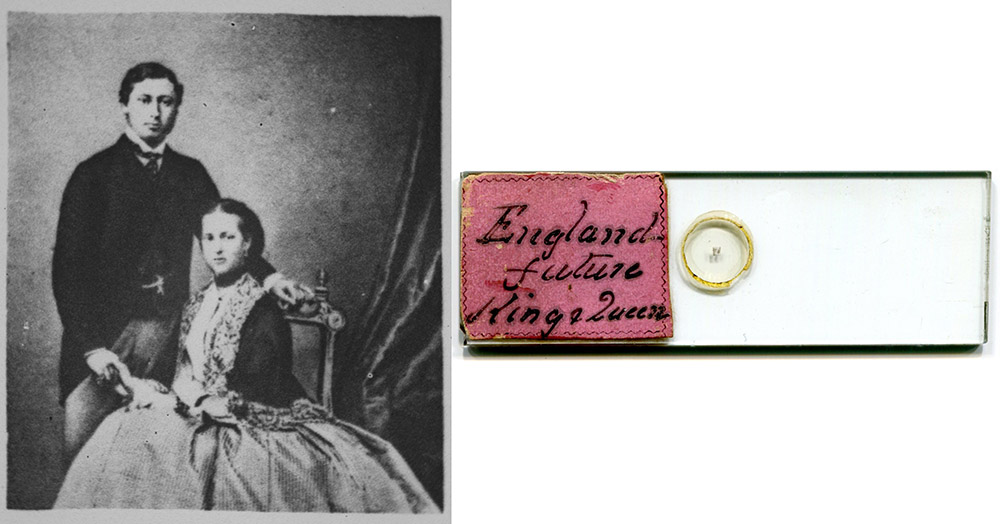

About the year 1865 the carte de visite was first introduced by a photographer, and these little photographs at once became popular with the public, and threatened to supercede the stereoscopic pictures in public-favor. The success of the photographer in producing the carte de visite picture was not followed up by many whose situation would have enabled them to obtain custom. The stereoscopic and carte de visite was the key that opened the door of palaces of emperors and princes to the plebeians; for these pictures gave correct likenesses of the inhabitants of these magnificent residences and also of the buildings themselves. The carte de visite picture was a very great saving of money, and they were therefore distributed more freely as personal favors by one among one's friends, even among the lower classes. Autographs generally accompanied the carte de visite, and sometimes they were sent as a present with a diamond ring or gold pencil case instead of a colored miniature, as had formerly been the custom.

The enlargements of pictures from small negatives was no longer a secret in the hands of a few. I did my utmost to help photographers with a machine to easily accomplish the production of enlarged pictures. About the year 1865, the discovery was made that magnesium was not so rare as was hitherto supposed. It had formerly only been seen in the cabinets of scientific collectors of rare metals, etc., but now magnesium was sold by a firm in Manchester in the form of very small wires about seventy to eighty yards to an ounce, and this wire, when set fire, burned with a splendid white flame which was suitable for making photographs. I purchased with much difficulty one-quarter of an ounce for twenty-one shillings. I was much excited over this discovery, and thought from the light so near sunlight that it would greatly benefit the photographers of London, where so many dark days prevailed in the winter, and thought it would also help photographers to work at night. I thought it might also be used for the magic lantern, but the manufacturer of the metal could not produce it free from alloy with other matter. I had this light adapted to the machine for enlarging small pictures, which it did in many instances, before rock oil was better understood. For some years I made the sale of magnesium the specialty of the house with which I was connected, and I have no doubt I was the best customer of the manufacturer of that metal. I may mention that one customer of mine, a Mr. Parker, an antiquarian, and photographer of grottos and dark places, kept in his employ a photographer especially to make photographs by the aid of magnesium.

At a meeting of the London Photographic Society, almost if not the last one under Baron Pollock, the honored and revered judge who was president of the society, there were shown to the members some large pictures on paper which were unlike anything that had hitherto been seen. They consisted of landscapes, and were prints that had been discovered in the studio of Watt, the great engineer and partner of the manufacturer Ballou, of Birmingham. It was said that the studio had been closed for many years after the death of Watt, and had only just been opened by a descendant who found with these prints a camera obscura. The President and others thought that these prints were produced by photographic means, but the color was a deep brown, one that could not have been acquired by age. They were not lithographs, and it could not be decided upon by the learned members just what they were. If the descendants of Watt have in their possession information found in the old studio, the present advanced knowledge of chemistry and other scientific studies might enable us to solve this apparent mystery.

Figure 9. Gravestone of Joseph Israel Solomon, Salem Fields Cemetery, Brooklyn, New York, USA. Adapted from http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=133685057&ref=acom.

Acknowledgement

Many thanks to Maureen Carter for sharing pictures and information.

Resources

Early Photography (accessed March, 2015) Joseph Israel Solomon, http://www.earlyphotography.co.uk/site/companies4.html

England census, marriage and death records, accessed through ancestry.co.uk

Find-a-Grave (accessed March 2015) http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=133685057&ref=acom

Histoire des Projections Lumineuses (accessed March, 2015) Images of a Solomon magnesium lamp, adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes

The Lancet (1854) Advertisement from J. Solomon, Vol. 2, July 7, general advertiser

Journal of the Society of Arts (1860) Vol. 8, page 311

London Electoral Register (1835) accessed through ancestry.co.uk

London Gazette (1878) Bankruptcy of Joseph Solomon, August 2

The Mayer Trust (accessed March 2015) http://www.themayertrust.org.uk/joseph.html

Notes & Queries (1854) Advertisement from J. Solomon, Vol. 10, page 337

Official Catalogue of the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations (1851) Entry of J. Solomon (page 63) and advertisement (advertiser, page 9)

Photographic Notes (1858) Advertisements from J. Solomon, Vol. 3, page 258

The Quarterly Journal of Science (1867) Advertisement from J. Solomon, Vol. 2, April advertiser<����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������/p>

Schechter, Frank I. (1916) An unfamiliar aspect of Anglo-Jewish history, Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society, No. 24

Solomon, Joseph (1863) Photographic Wrinkles, Remedies, and Recipes, London, pages 62-64

Solomon, J. (1887) Recollections of the early days of photography, The Photographic Times and American Photographer, Vol. 17, pages 304-305, 314-315, 334-335, 351-352, 363-364, and 374-375

Spielmann, Marion H. (1895) The History of “Punch”, Vol. 1, Cassell & Co., London, page 124

Warren, Stanley (2009) Studying microphotographic slides, an update to current knowledge, Journal of the Microscope History Society, Vol. 17, pages 35-50. A Solomon slide is shown in Figure 5, page 43

The Year-Book of Photography (1884) Advertiser, pages lxxxii and lxxxiii

The Year-Book of Photography (1885) Advertiser, pages vi and vii