Ca. 1840 microscope slide that is labeled "Insect from Tortois". Note that ticks are arachnids, not insects, and the nymph and adult stages have eight legs. This is a deep mount of an unflattened, uncleared tick immersed in balsam.

Microscope Slides of Ticks,

from the early 1800s until recently

by Brian Stevenson

last updated June, 2024

Blood-sucking arthropods were among the first specimens to be investigated through the microscope. Fleas and lice were commonly mounted in ivory sliders during the 1700s, being small and flat (and thus easy to mount without any preparation), and people were curious to see details about these common pests.

Ticks are much thicker than fleas or lice, and permanent mounts of ticks were difficult to produce until techniques were developed during the 1800s to clear and flatten arthropods.

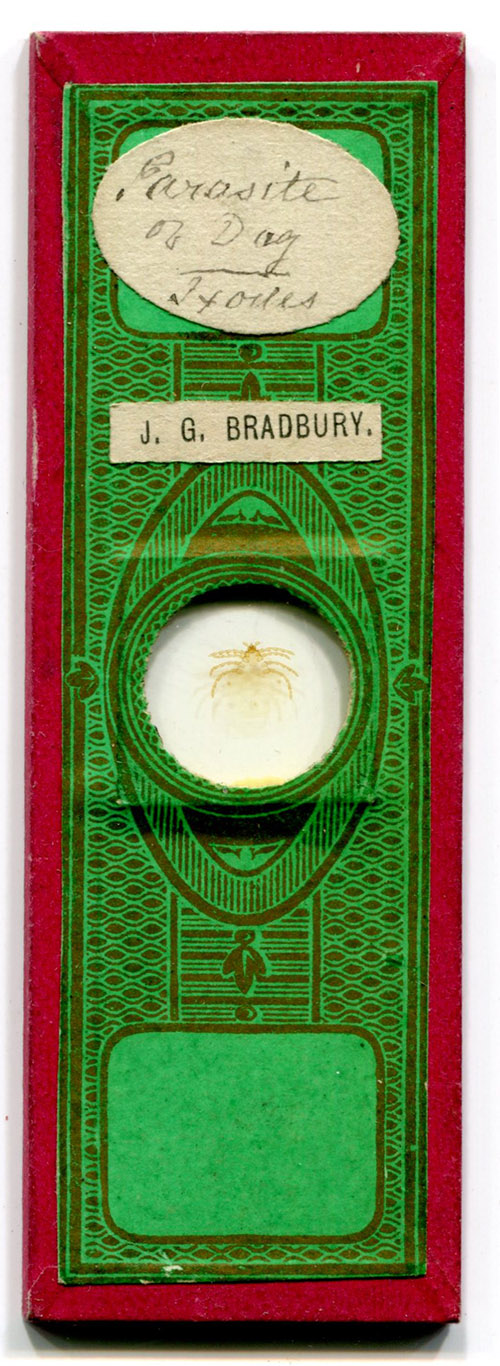

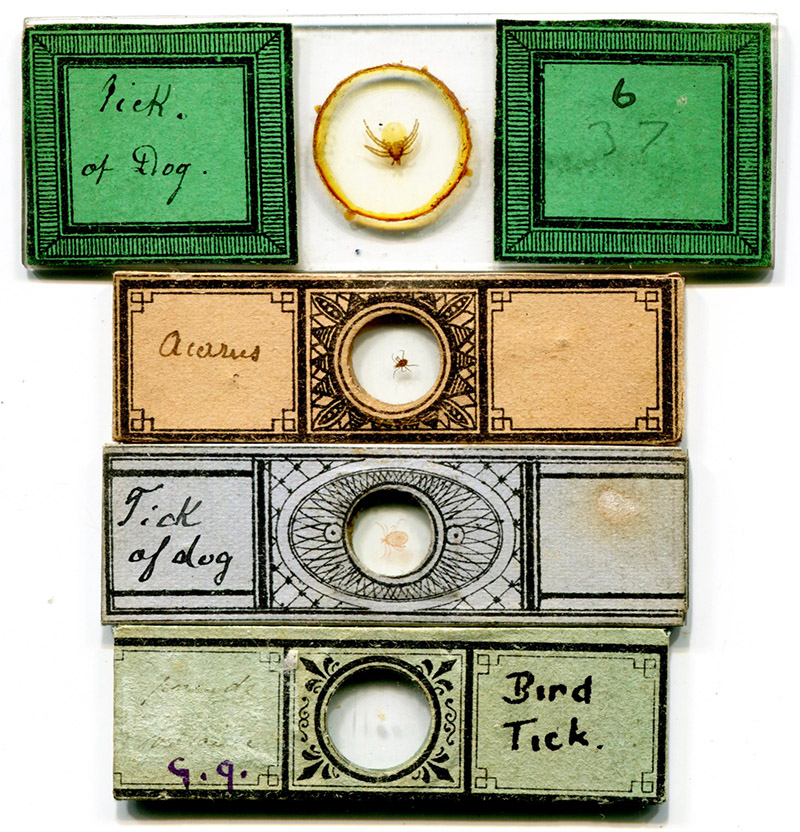

My day job involves studies of tick-borne diseases, so ticks hold a special appeal. Following are slides of ticks from my collection. Early mounters variously described ticks as "Ixodes" (an early name for ticks, all ticks are now classified in the Order Ixodida, and a genus is now named Ixodes), "Acari" (ticks and mites are in the subclass Acari, and class Arachnida with the spiders), or simply "Parasite".

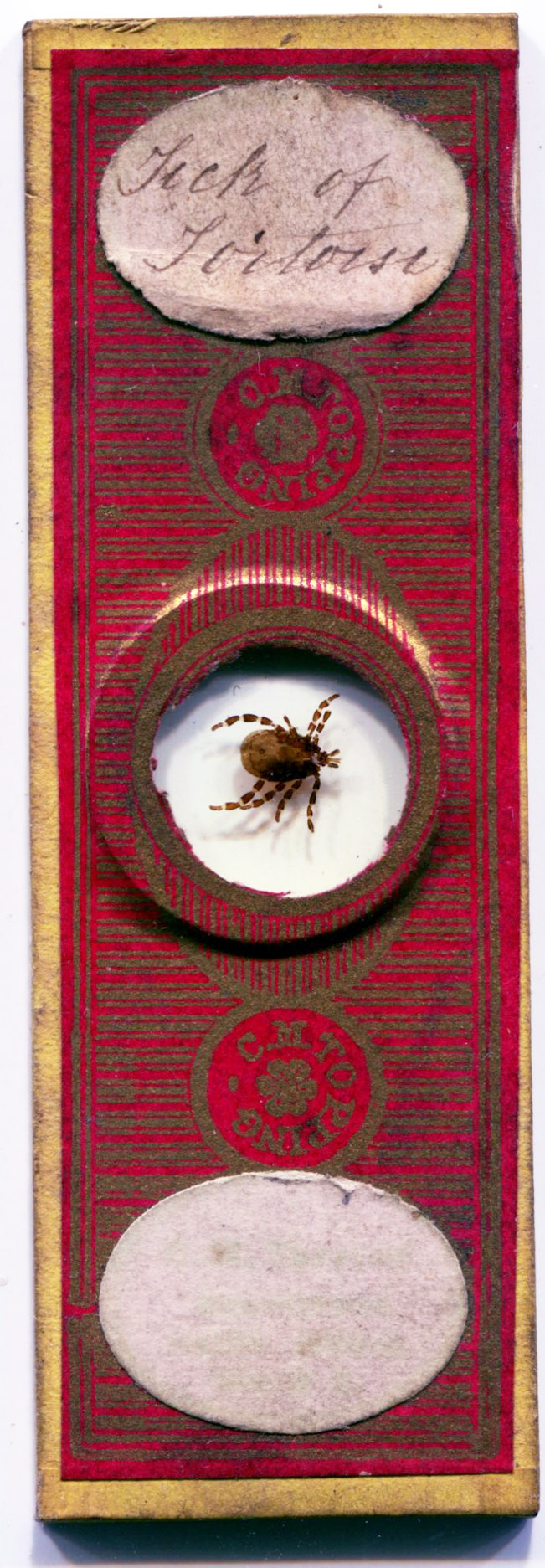

Ca. 1840 microscope slide that is labeled "Insect from Tortois". Note that ticks are arachnids, not insects, and the nymph and adult stages have eight legs. This is a deep mount of an unflattened, uncleared tick immersed in balsam.

Two slides by professional slide-maker James W. Bond (1803-1887). The left slide may date from the 1840s, the right slide probably 1850s.

"Parasite of Pheasant" and "Acarus Ricinus", prepared ca. 1850 by professional slide-maker Cornelius Poulton (1814-1854). Poulton cut off the posterior of the larger, right-hand specimen, to facilitate clearance of the internal organs.

"Tick of tortoise", prepared ca. 1870 by professional slide-maker Charles M. Topping (1799-1874).

Two early slides, probably from continental Europe. They are part of a set of approximately 30 slides of dissected arthropods. Prepared from two thick pieces of glass, sealed with balsam, and papered on front and back only. They are longer and narrower than the standard 1x3 inch, of which a twentieth century slide by an unknown maker is shown for size comparison.

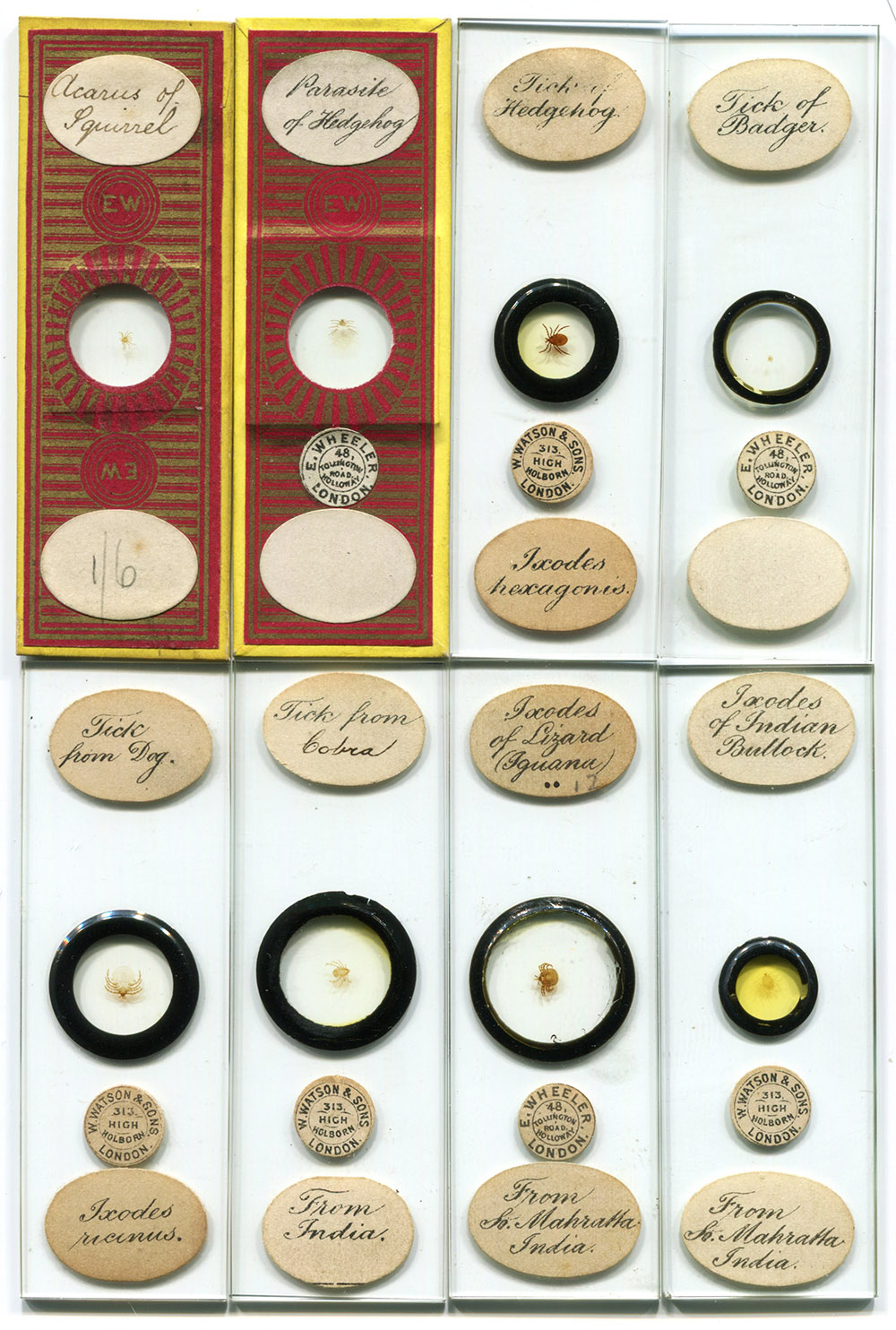

Preparations by professional slide-maker Edmund Wheeler (1808-1884). Wheeler sold his stock of 50000+ slides to Watson and Son just before his death, and Watson continued to sell them for many years after.

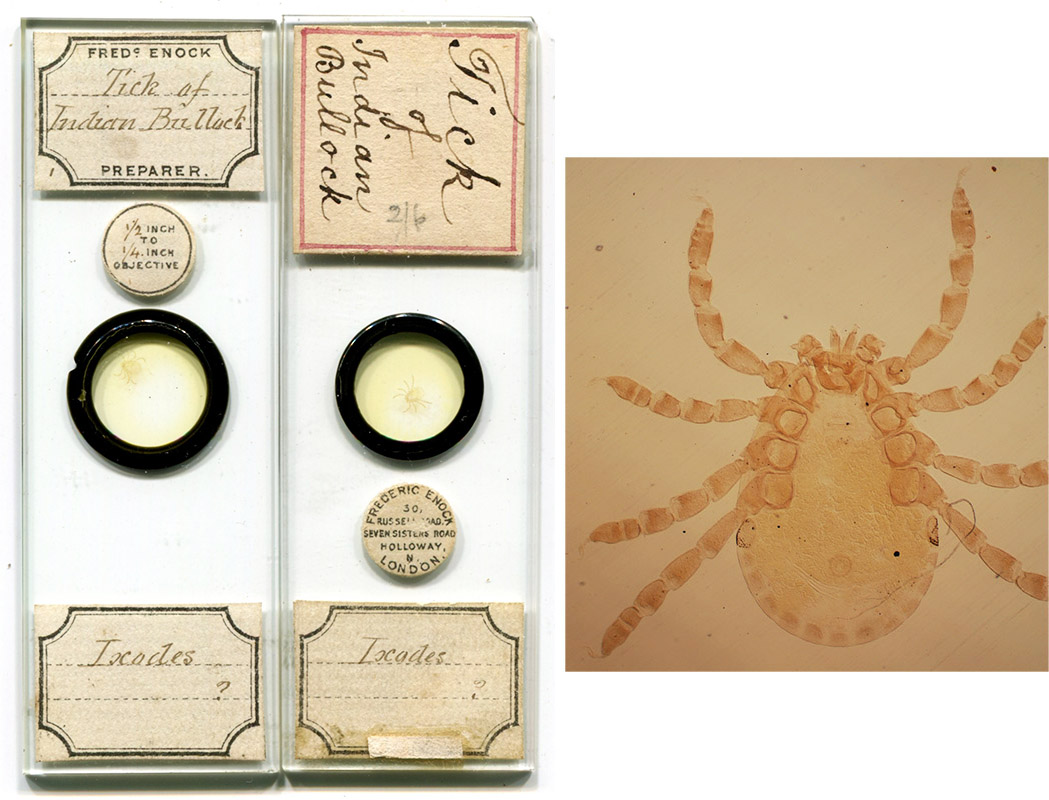

Tick of Indian bullock, by professional slide-maker Frederic Enock (1845-1916). Enock was a nephew of Edmund Wheeler, and joined his uncle’s business in about 1870. He started his own business around the time of Wheeler’s death in 1884. The top label of the right slide is not by Enock, it was added by an owner, possibly to facilitate identification when stored in a horizontal position.

Tick of a shrew, by an unknown English amateur mounter. Based on other slides from this maker which were marked with dates, this was probably made during the mid-1850s. The specimen is a tick larva (larvae have 6 legs), probably Ixodes trianguliceps (formerly I. tenuirostris).

Mounts by professional slide-makers John T. Norman (1807-1893) and/or his sons.

A professionally-prepared slide of a tick by John Barnett (1816-1882).

ca. 1870 mounted tick, from the collection of George E. Quick (1831-1908).

Slides of various ticks attributable to the Bourgogne family (ca. second half of the nineteenth century): one standard and three small "continental"-sized slides.

Slides by professional Herbert William Hutton Darlaston (1867-1949). The slide on the left has a rare label with Darlaston’s initials, "H.W.H.D.", an example of his early work. The slide on the right holds a "soft" tick, Argas miniatus. A nineteenth century report found these on cattle in the U.S.A., and called it by the now-invalidated name of Argas americana, as used here by Darlaston. Argas miniatus primarily infests chickens and other birds.

Professional slides by Alfred Cole (1821-1900) and Richard Suter (1864-1955).

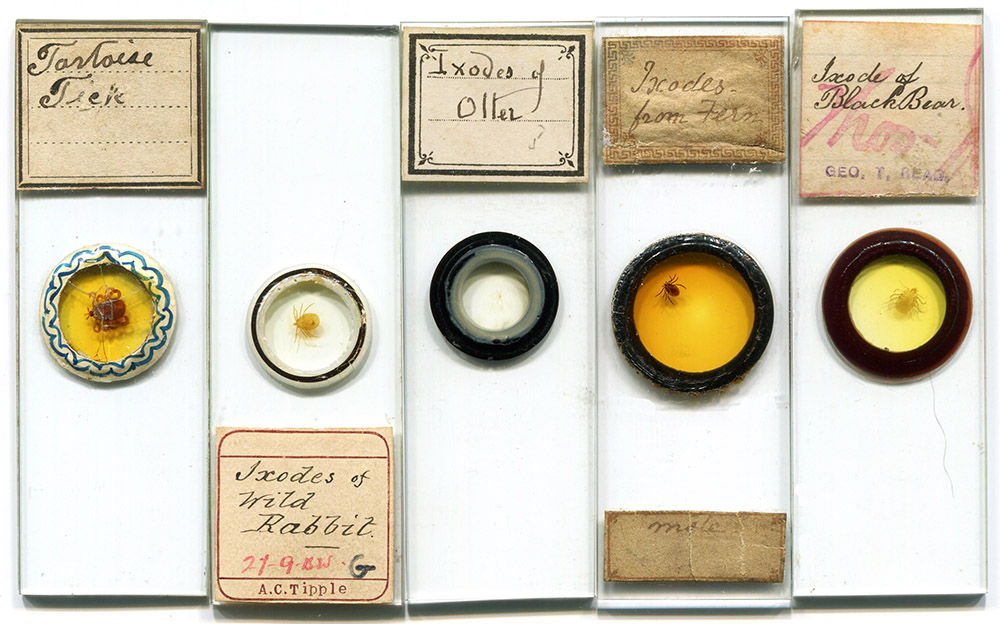

Amateur slides by, left to right, James Neville (1840-1900), Alfred Tipple (1850-1887), J.C. Tempère (1840-1900), an unidentified slide-maker, and George Read.

Some exotic ticks by English amateur microscope slide-maker Edward Horsnaill (1836 - 1913).

ca, 1880 female Dermacentor variabilis, by Eduard Huber

(1845-1906

).

"Female Cattle Tick Rhipicephalus decoloratus", circa 1910, by Richard Hancock (1870-1952).

Slides by, left to right, an unknown microscopist, Robert Pettigrew (1868-1953), John Boyd (1852-1929), and John Young (who misidentified a tick for the mouse mite Myobus musculinus).

Amateur slides attributed to John Bramhall (1809-1889).

An amateur slide of a larval tick (note 3 pairs of legs), by R. Harrison, of Hull, England. Circa 1870.

Two slides of ticks from Central America, one of which is dated 1860. The left slide bears an adult, described as "Garapata or Cattle Tick", the left holds several larvae, apparently removed from a freshwater turtle in Izabal, Guatemala. It is not uncommon for turtles to be infested. Recent studies demonstrated that ticks can survive for many days when submersed in water.

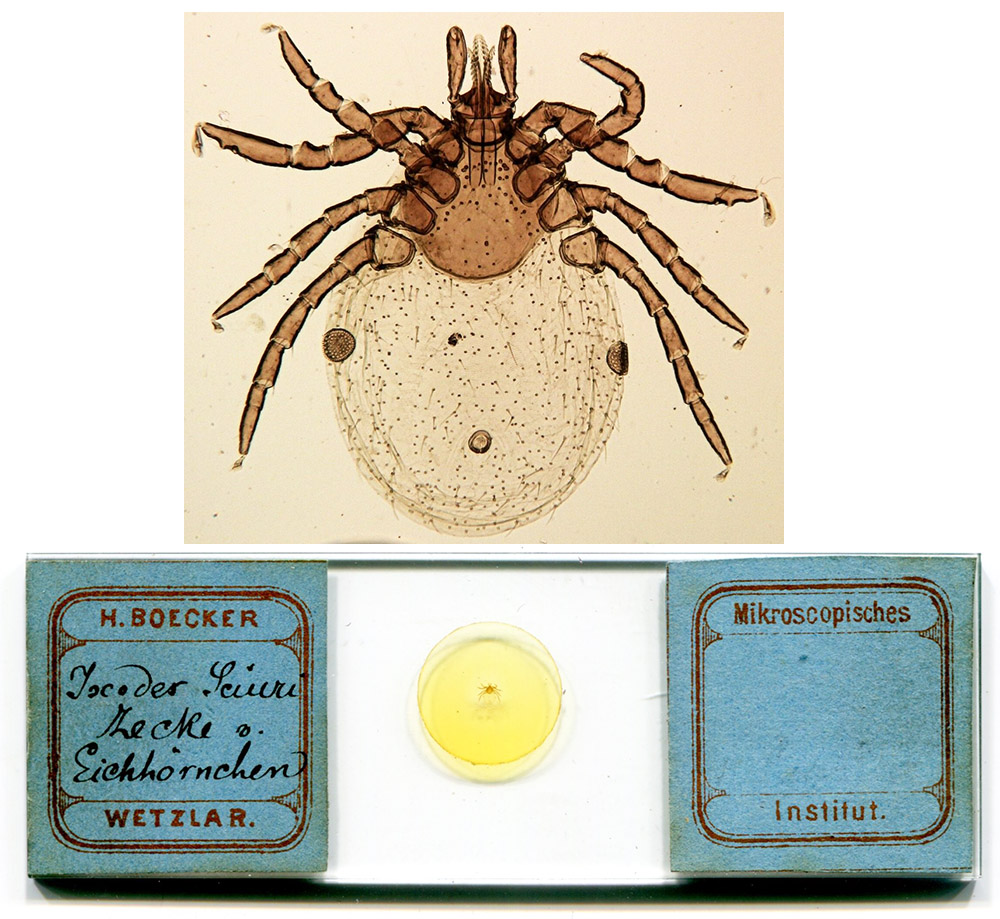

Mount by professional slide-maker Heinrich Boecker, ca. 1880. He described the this as a tick from an Eichhornchen (squirrel) - it appears to be a specimen of Ixodes ricinus.

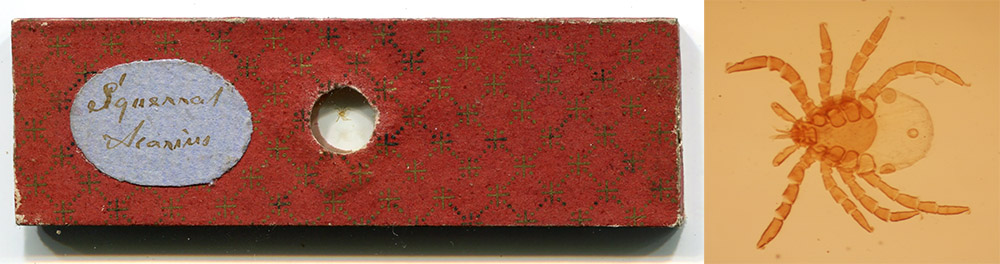

"Squirrel Acarus" by an unknown mounter, circa 1860.

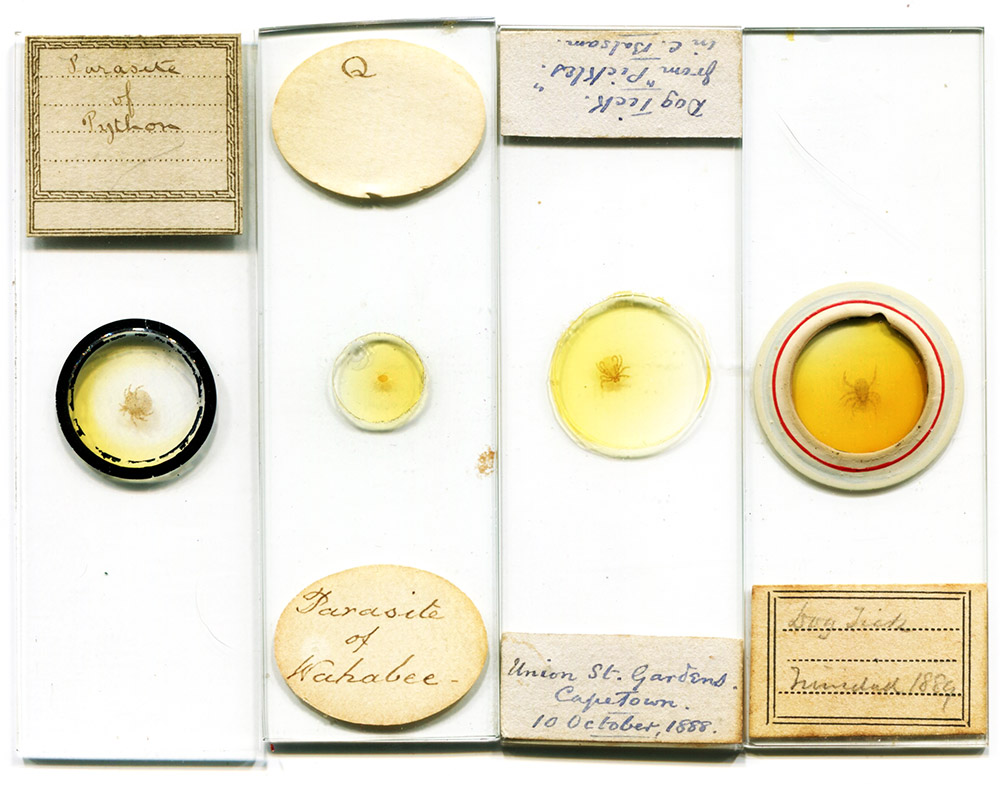

Four amateur slides of ticks, from a python, a "wahabee", and dogs from Capetown, South Africa (1888) and Trinidad (1889). By unknown mounters.

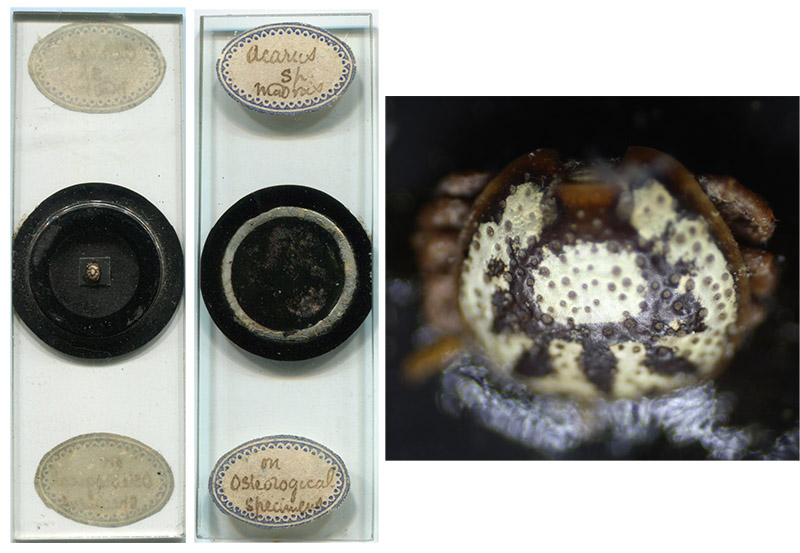

Dry-mount of an ornately-patterned tick, described as being from Madras, India, and found on an "osteological specimen". The head is absent, suggesting forced removal during feeding. The maker applied the labels to the reverse of the slide.

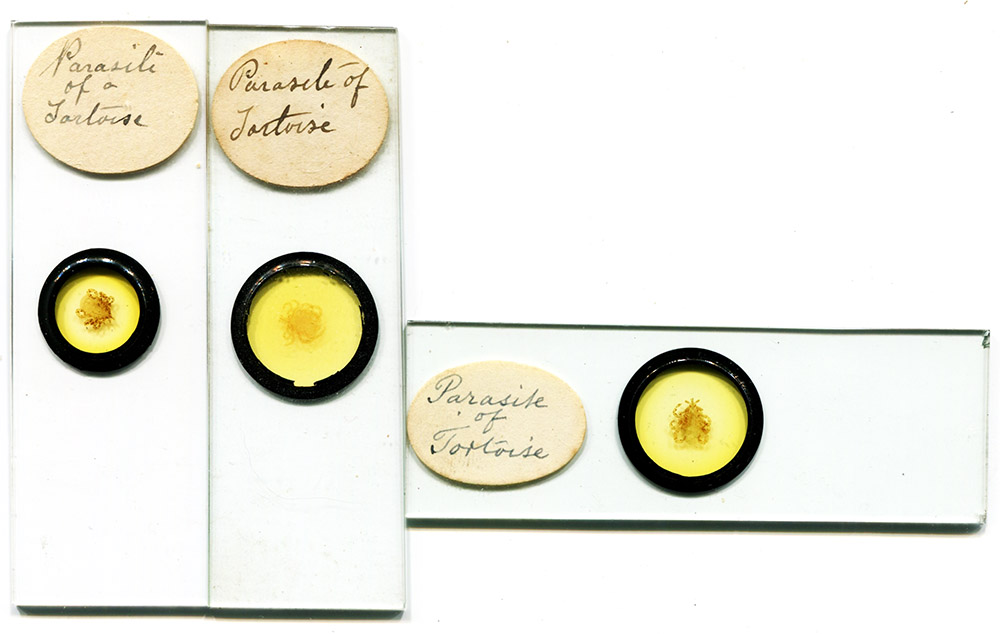

Three slides of ticks from a tortoise, of English origin. All three appear to have the same handwriting. The maker is not known, but may have been a professional, since many slides are known that have this handwriting.

Mouthparts ("lancets") from "parasite of tortoise", by Thomas D. Russell, London.

Circa 1880 preparation of a female adult Ixodes ricinus by Rudolf Getschmann, Berlin.

Tick mount from Dr. Eduard Kaiser’s Institut für Mikroskopie, Berlin. Circa 1890. The specimen appears to be the nymph stage of Ixodes ricinus, which is fairly common around Berlin.

"Larval cattle ticks from Queensland", Boophilus microplus. The ticks were evidently provided by Charles Joseph Pound (1866-1946), bacteriologist and entomologist of the Animal Research Institute, Queensland, Australia. Pound identified these ticks as the vectors of "redwater fever" during the 1890s.

Most people are familiar with "hard" (ixodid) ticks, and the vast majority of slides are of such ticks. The "soft" (argasid) ticks comprise another major family of ticks, but are relatively fast feeders and are rarely seen by people. These are rather uncommon slides of an African argasid tick, Ornithodorus moubata, which may transmit relapsing fever. An adult male and a nymph are shown. The nymph was photographed with either normal brightfield (top, right) or between crossed polarizing filters (bottom, right)

Another, undated slide of an Ornithodorus moubata nymph.

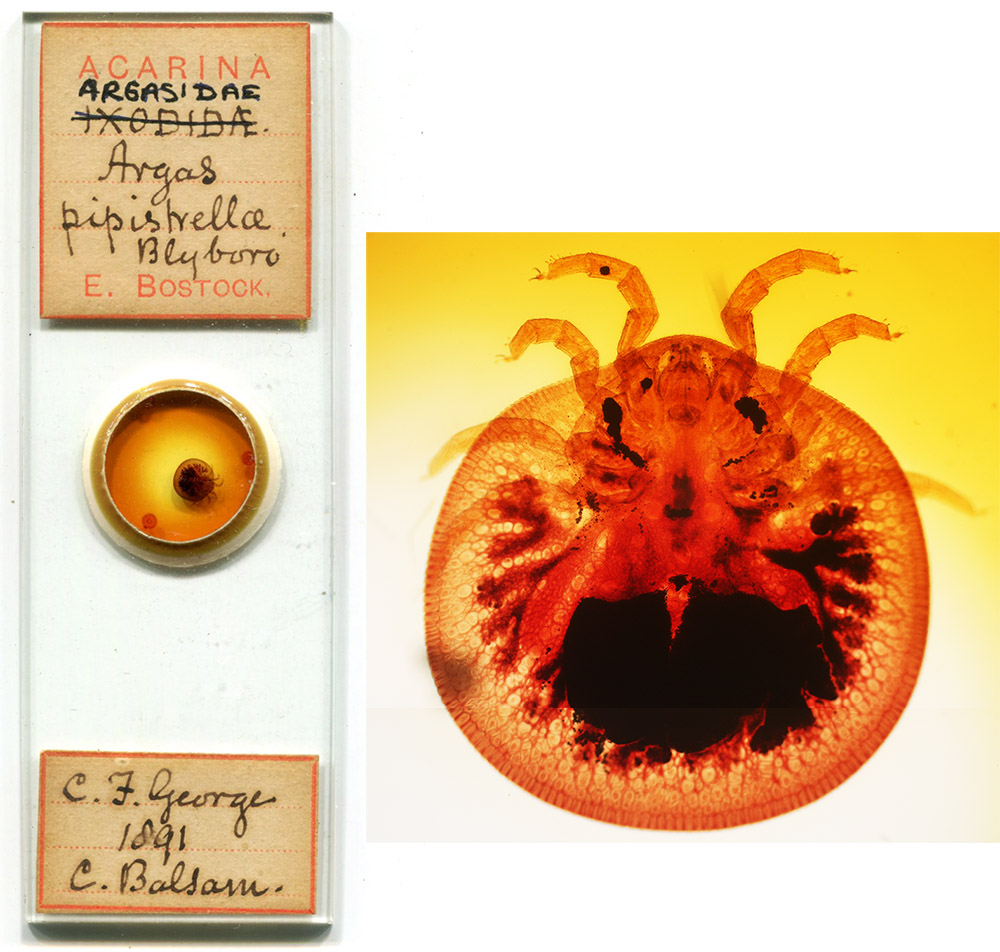

Another species of argasid tick, initially described as Argas pipistrellae, but now named Carios vespertilionis, prepared in 1891 by Edwin Bostock (1838-1901). Bostock originally labeled this specimen as an "Ixodidae", which was corrected to "Argasidae" at a later date.

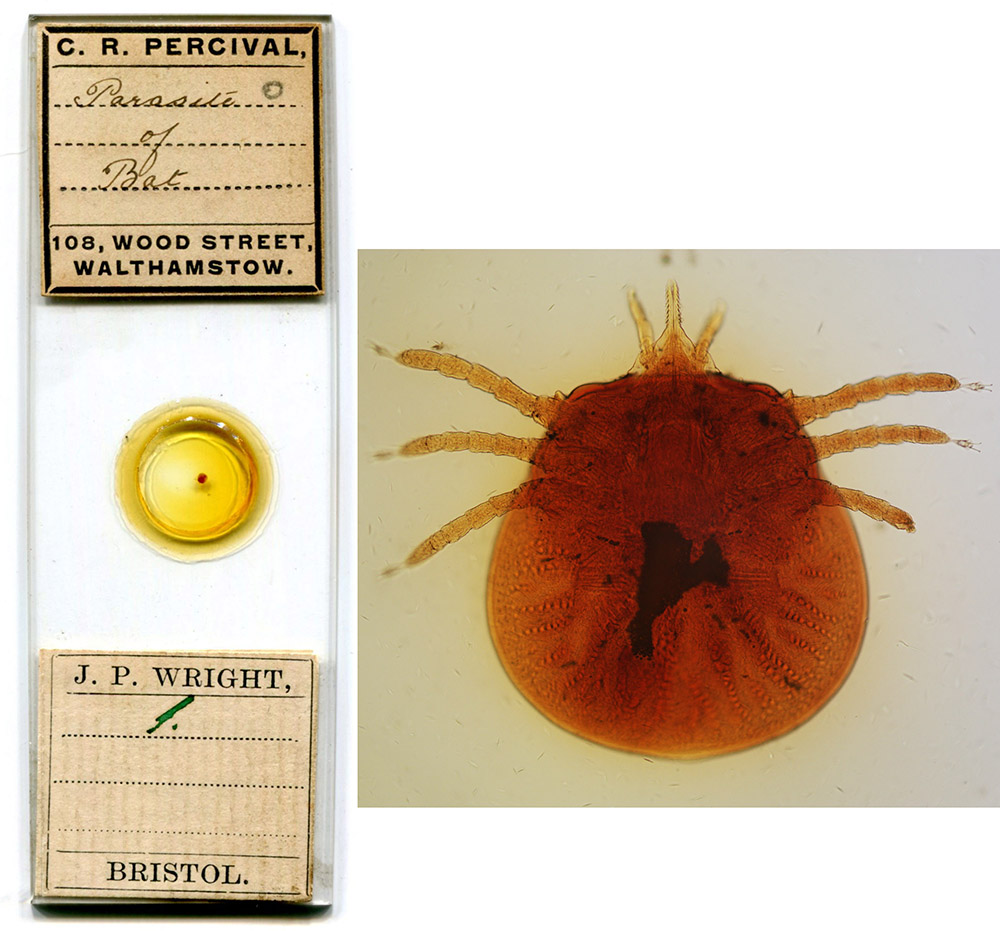

A larva of Carios vespertilionis, prepared ca. 1905 by Charles R. Percival (1879-1960). The lower label indicates that it was once owned by Joseph P. Wright (1855-1942), who is known to have purchased slides from Percival at that time.

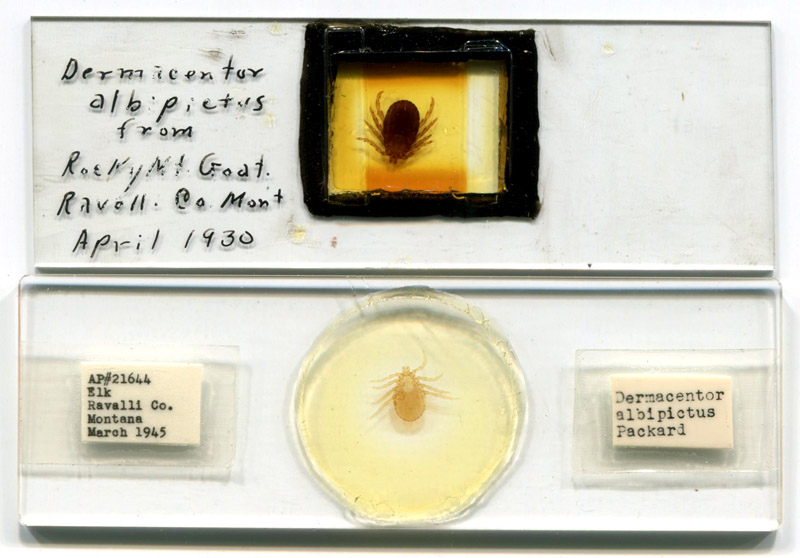

Two slides, dated 1930 and 1945, by tick-borne disease researcher William L. Jellison (1906-1995).

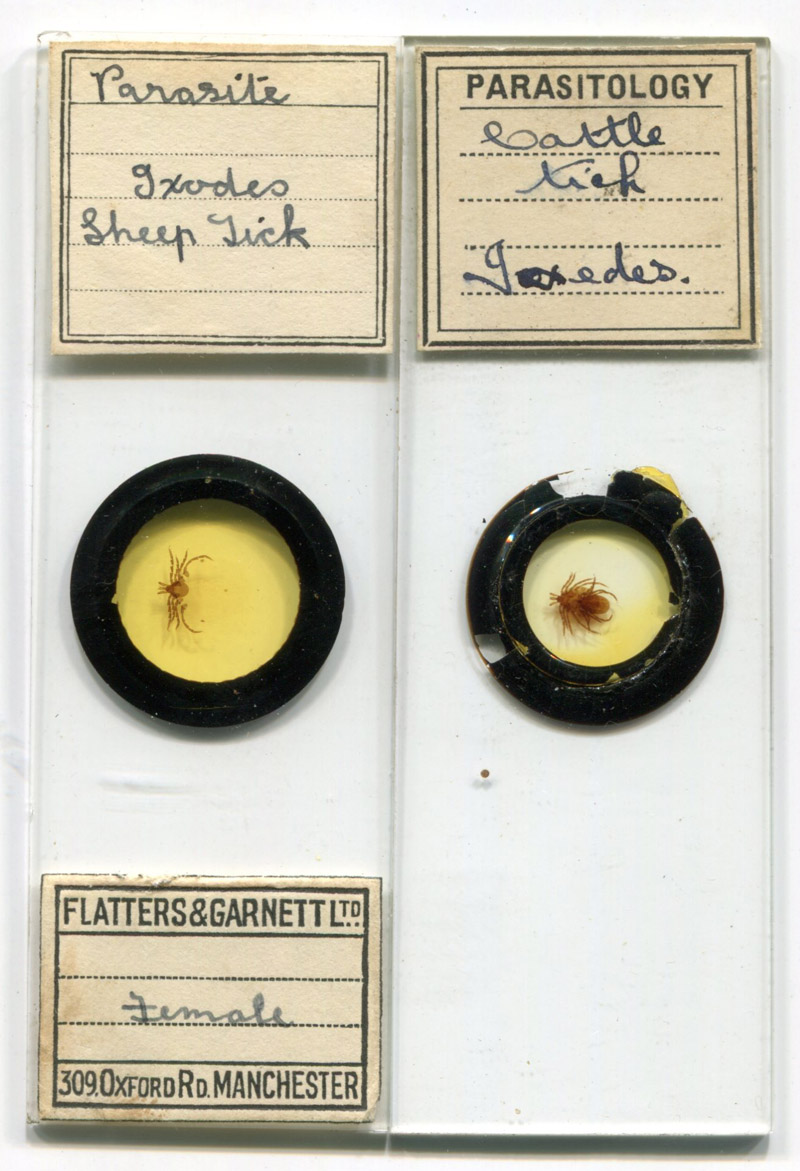

Two professionally prepared slides from the twentieth century, by Flatters and Garnett, and by A. Lister. The Lister slide holds a copulating pair of ticks.

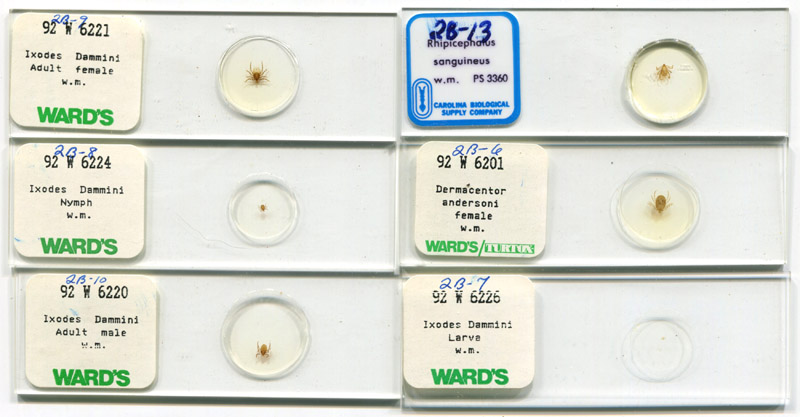

Late twentieth century slides of Ixodes scapularis ("dammini"), Dermacentor andersoni and Rhipicephalus sanguineus, by Ward’s and Carolina Biological.

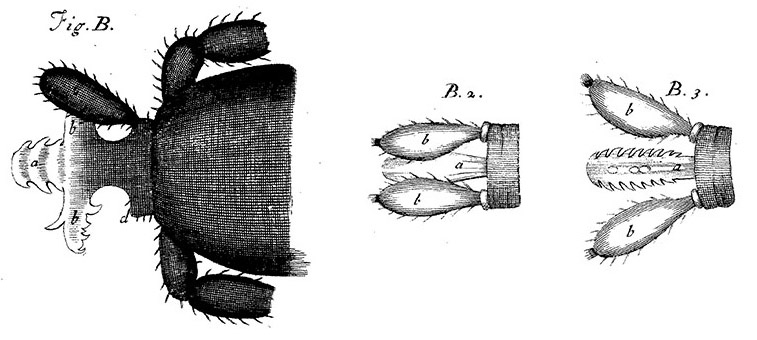

Possibly the earliest description of ticks, as seen through a microscope. An anonymous microscopist wrote of these, and many other discoveries, that were found through use of the newly-invented Wilson Screwbarrel Microscope, in "Philosophical Proceedings" during 1702-1703, Vol. 23, pages 1357-1372, http://rstl.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/23/277-288.toc.

Acknowledgement

Many thanks to Tom Schwan, my generous mentor on acarology and microscopy.